Summary

Selective expansion of T cells bearing specific T cell receptor Vβ segments is a hallmark of superantigens. Analyzing Vβ specificity of superantigens is important for characterizing newly discovered superantigens and understanding differential T cell responses to each toxin. Here, we described a real-time PCR method using SYBR green I and primers specific to Cβ and Vβ genes for an absolute quantification. The established method was applied to quantify a selective expansion of T cell receptor Vβ expansion by superantigens and generated accurate, reproducible, and comparable results.

Keywords: superantigen, T cell receptor Vβ, quantitative real time PCR

1. Introduction

The T cell receptor (TCR) is a α and β chain heterodimer that recognizes antigen-derived peptides presented by the major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II) molecules on antigen presenting cells, thereby triggering a clonal expansion of T cells [1]. The TCR consists of a variable and constant region, where the variable region interacts with peptide and MHC II, thus determining the antigen specificity of T cells [2,3]. A high diversity of the variable region of TCR is generated by a somatic recombination of variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) genes with a constant (C) gene and imprecise joining of VDJ segments during thymic development [4]. Cloning and sequencing human Vβ genes have identified 49 functional Vβ subgroup genes. Based on the sequence similarity, these genes were grouped in 24 different Vβ groups. Due to the sequence variations, some Vβ groups contains multiple subgroups [2,5,6].

Staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs), SE-like toxin (SEl), and toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1) are prototypical microbial superantigens (SAg). Thus far, 23 SEs and SEls including SEA through X, excluding F, and TSST-1 have been characterized in Staphylococcus aureus [7]. Unlike conventional antigens, most SAgs directly bind to the specific variable regions of TCR β chain (Vβ) and outside of the peptide binding groove of MHC II. This binding triggers a clonal expansion of T cells bearing specific TCR Vβ segments, leading to a massive production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [8]. Thus, SAgs induce antigen-independent, Vβ-dependent T cell proliferation. The shared biological properties of SAg such as Vβ specificity and cytokine responses were closely correlated with the amino acid sequence and 3 dimensional structure of SAgs. Therefore, the analysis of Vβ specificity of SAg is important for characterizing newly discovered SAg and understanding T cell responses to the SAg.

Several approaches are used to analyze the Vβ specificity of SAg including northern blotting, semi-quantitative PCR [9], and flow cytometry using monoclonal antibodies specific to Vβ segments [10,11]. Shortcomings such as a lack of available reagents limit the practical application of these approaches. We developed a quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) method using SYBR green I and primers specific to 22 Vβ groups and constant β chain (Cβ) genes [12]. The specificity of established method was verified by sequencing PCR amplification products showing that 36 out of 49 functional Vβ subgroup genes were successfully amplified. Standard curves for primers to Cβ and Vβ genes were generated to allow an absolute quantification. The established method was applied to assess the Vβ specificity of SAgs and showed reproducible and comparable results from previous approaches.

2. Materials

2.1. Preparation and stimulation of enriched human lymphocytes

1. BD Vacutainer Saftey-Lok Blood collection set

2. Blood collection tube containing Heparin

2. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS)

3. Ficoll-Hypaque plus solution (density 1.077g/liter)

4. Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS)

5. Complete RPMI1640 medium: RPMI medium supplemented with 2 % FBS, 100 U penicillin G, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

7. Beckman GPR centrifuge with GH-3.7 horizontal rotor (or equivalent temperature-controlled centrifuge)

8. Endotoxin free SAg

9. Murine monoclonal antibody (mAb) specific to human CD3 (Sigma-Aldrich)

2.2. RNA extraction

1. RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen)

2. RNase free TURBO DNase I (Ambion)

3. 70% ethanol

2.3. cDNA synthesis

1. DNA, RNA-free 0.2 ml PCR tube

2. Thermocycler

3. dNTP mix (10 mM each, Life technologies)

4. oligo(dT)20 (0.5μg/μl, Life technologies)

5. Superscriptase III first strand synthesis kit (Life technologies)

2.4. Quantitative real time PCR

1. Applied Biosystems 7500 real time PCR system or equivalent real time PCR thermal cycler

2. MicroAmp Optical 96-well reaction plate (Life Technologies)

3. MicroAmp Optical plate seals (Life Technologies)

4. Power SYBR Green PCR Master mix (Life Technologies)

5. Primers specific to the Cβ and Vβ gene

3. Methods

3.1. Preparation and stimulation of enriched human lymphocytes.

1. Collect whole blood (10 −20 ml) from the healthy donor by venipuncture using BD Vacutainer Saftey-Lok Blood collection set (21G needle) and Blood collection tube containing Heparin (14U/ml blood).

2. Transfer whole blood into the 50 ml conical polypropylene tube and add an equal volume of PBS. Mix well.

3. Slowly overlay the diluted blood onto the Ficoll-Hypaque plus solution. Use 1 ml Ficoll-Hypaque per 3 ml blood diluted with PBS.

4. Centrifuge at 2000 rpm (900×g), 18 – 20°C for 30 min without brake.

5. Using sterile pipet, carefully remove the upper layer containing the plasma and platelets and discard. Using another pipet, carefully transfer buffy coat that contains the mononuclear cells to the 50 ml conical polypropylene tube.

6. Wash mononuclear cells three times by adding 45 ml of HBSS and centrifuging at 1300 rpm (400×g), 18 −20°C for 10 min (see Note 1).

7. Resuspend the cells in complete RPMI medium and culture in cell culture Petri dishes (Costar) overnight at 37°C and in 5 % CO2.

8. The following day, non-adherent, lymphocyte-enriched cells are collected, washed, and resuspended in complete RPMI medium at a final concentration of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml.

9. Each SAg (0.5 μg/ml) is added to lymphocyte-enriched cells. Cells are cultured for 4 days (37°C, 5 % CO2) and harvested by centrifuging at 1300 rpm (400×g), 4°C for 10 min.

3.2. Total RNA extraction

1. Approximately 5 × 106 cells are resuspended in 350 μl of buffer RLT and homogenized by passing the lysate 10 times through a 20 gauge needle (see Note 2).

2. Centrifuge the lysate at 12000×g for 3 min and carefully transfer the supernatant to a new microcentrifuge tube.

3. Add an equal volume of 70% ethanol and mix by pipetting.

4. Transfer the mixture to the RNeasy spin column and centrifuge at 8000×g for 15 sec and discard the flow through.

5. Add 700 μl Buffer RW1 to the RNeasy spin column and centrifuge at 8000×g for 15 sec and discard the flow through.

6. Add 500 μl Buffer RPE to the RNeasy spin column and centrifuge at 8000×g for 15 sec and discard the flow through.

7. Add 500 μl Buffer RPE to the RNeasy spin column and centrifuge at 8000×g for 2 min and discard the flow through.

8. Place the RNeasy spin column in a new microcentrifuge tube and add 50 μl RNase-free water directly to the spin column membrane. Centrifuge at 8000×g for 1 min.

9. Add RNase-free water to make the volume up to 89 μl.

10. Add 10 μl 10× TURBO DNase Buffer and 1 μl TURBO DNase (2U/μl)

11. Incubate at 37 °C for 30 min.

12. Add 350 μl Buffer RLT and mix well by pipetting.

13. Add 250 μl 100% ethanol and mix well by pipetting.

14. Transfer the mixture to a new RNeasy spin column and centrifuge at 8000×g for 15 sec and discard the flow through.

15. Add 500 μl Buffer RPE to the RNeasy spin column and centrifuge at 8000×g for 15 sec and discard the flow through.

16. Add 500 μl Buffer RPE to the RNeasy spin column and centrifuge at 8000×g for 2 min and discard the flow through.

17. Place the RNeasy spin column in a new microcentrifuge tube and add 50 μl RNase-free water directly to the spin column membrane. Centrifuge at 8000×g for 1 min.

18. Determine the quantity and quality of RNA using Nanodrop and adjust the quantity to 1 μg/5 μl (see Note 3).

3.3. cDNA synthesis

1. Add the following in a 0.2 ml PCR tube:

5 μl total RNA (1 μg)

1 μl dNTP mix (10 mM each dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP)

1 μl oligo(dT)20 (500 ng)

7 μl RNase-free water

2. Incubate for 5 min at 65°C, then place on ice for 2 min

3. Add the following cDNA Synthesis Mix to the tube.

4 μl 5 × Reverse Transcriptase Buffer

1 μl 0.M DTT

1 μl Superscriptase III RT (200 units/μl)

4. Incubate for 50 min at 50°C

5. Incubate for 5 min at 85°C to terminate the reactions, then place on ice

6. Dilute cDNA with 980 μl DNase-free water and store at – 80°C until used.

3.4. Primer design

Primers specific to the Cβ and 23 different Vβ groups were designed using Primer Express version 2.0 (Applied Biosystems). Some Vβ groups have multiple Vβ subgroups genes showing high sequence similarity. Therefore, some Vβ primers are expected to amplify multiple Vβ subgroup genes within the corresponding Vβ group. Sequencing analysis of PCR products generated using these primers showed that 36 out of 49 functional Vβ genes were amplified. The primer sequences and amplified Vβ subgroup genes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Primer name | GenBank access number | Forward primer (‘5 to 3’) | Reverse primer (‘5 to 3’) | Amplified Vβ gene(s)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cβ | L36092 | tccagttctacgggctctcg | gacgatctgggtgacgggt | |

| VB1 | L36092 | ggagcaggcccagtggat | cgctgtccagttgctggtat | TCRVB1s1 |

| VB2 | M11955 | gagtctcatgctgatggcaact | tctcgacgccttgctcgtat | TCRVB2s1 |

| VB3 | U08314 | tcctctgtcgtgtggccttt | tctcgagctctgggttactttca | TCRVB3s1 |

| VB4 | L36092 | ggctctgaggccacatatgag | ttaggtttgggcggctgat | TCRVB4s1 |

| VB5 | L36092 | gctccaggctgctctgttg | tttgagtgactccagcctttactg | TCRVB5s1, 5s3 |

| VB6 | X61440 | ggcagggcccagagtttc | gggcagccctgagtcatct | TCRVB6s1, 6s2, 6s3, 6s4, 6s5, 6s6 |

| VB7 | U07977 | aagtgtgccaagtcgcttctc | tgcagggcgtgtaggtgaa | TCRVB7s1, 7s2, 7s3 |

| VB8 | X07192 | tgcccgaggatcgattctc | tctgagggctggatcttcaga | TCRVB8s1, 8s2, 8s3 |

| VB9 | U07977 | tgcccgaggatcgattctc | tctgagggctggatcttcaga | TCRVB9s1 |

| VB11 | L36092 | catctaccagaccccaagatacct | atggcccatggtttgagaac | TCRVB11s1 |

| VB12 | U03115 | gttcttctatgtggccctttgtct | tcttgggctctgggtgattc | TCRVB12s1, 12s3 |

| VB13c | L36092 | tggtgctggtatcactgaccaa | ggaaatcctctgtggttgatctg | TCRVB13s1, 13s6 |

| VB13d | X61445 | tgtgggcaggtccagtga | tgtcttcaggacccggaatt | TCRVB13s2, 13s9 |

| VB14 | L36092 | gctccttggctatgtggtcc | ttgggttctgggtcacttgg | TCRVB14s1 |

| VB15 | M11951 | tgttacccagaccccaagga | tgacccttagtctgagaacattcca | TCRVB15s1 |

| VB16 | X06154 | cggtatgcccaacaatcgat | caggctgcaccttcagagtaga | TCRVB16s1 |

| VB17 | U48260 | caaccaggtgctctgctgtgt | gactgagtgattccaccatcca | TCRVB17s1 |

| VB18 | L36092 | ggaatgccaaaggaacgattt | tgctggatcctcaggatgct | TCRVB18s1 |

| VB20 | L36092 | aggtgccccagaatctctca | ggagcttcttagaactcaggatgaa | TCRVB20s1 |

| VB21 | M33233 | gctgtggctttttggtgtga | caggatctgccggtaccagta | TCRVB21s1 |

| VB22 | L36092 | tgaaagcaggactcacagaacct | tcacttcctgtcccatctgtgt | TCRVB22s1 |

| VB23 | U03115 | ttcagtggctgctggagtca | cagagtggctgtttccctcttt | TCRVB23s1 |

| VB24 | U03115 | acccctgataacttccaatcca | cctggtgagcggatgtcaa | TCRVB24s1 |

The pseudogenes (Vβ10 and Vβ19) were not included.

Vβ subgroup nomenclature followed the classification of Arden et al.

VB13A corresponds to Vβ13.1 in previous studies.

VB13B corresponds to Vβ13.2 in previous studies.

3.5. Quantitative real time PCR

3.5.1. Standard curve

For absolute quantification of the Cβ and Vβ genes, the standard curves for primers to Cβ and Vβ genes were generated.

1. The Cβ and Vβ genes were amplified by PCR using primers listed in Table 1. Each PCR product was purified using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and then cloned into pCR2.1 plasmid vector (Life Technologies). Cloned pCR2.1 plasmid vectors were purified using a plasmid MiniPrep kit (Qiagen) and the concentration of plasmid was determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm using a Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific). The plasmid copy number was determined by a following formula [13,14]:

Where:

X = the amount of plasmid (ng)

N = the size (base pair) of plasmid

2. Set up triplicate qRT-PCR reactions (25 μl each) consisting of:

12.5 μl Power SYBR Green PCR Master mix

5 μl (2 pmoles) forward and reverse primers (2.5 μl each)

5 μl 10-fold serially diluted plasmid template (2.5 – 2.5 × 105 copies)

2.5 μl DNase-free water

3. Thermocycler conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of a denaturation at 95°C for 15s and an extension at 60°C for 1 min. Fluorescent data is measured during an extension period. After 40 cycles, a melting curve analysis is performed. The base line and threshold cycle (CT) is determined using the Sequence Detector Systems version 1.2.2 (Applied Biosystems).

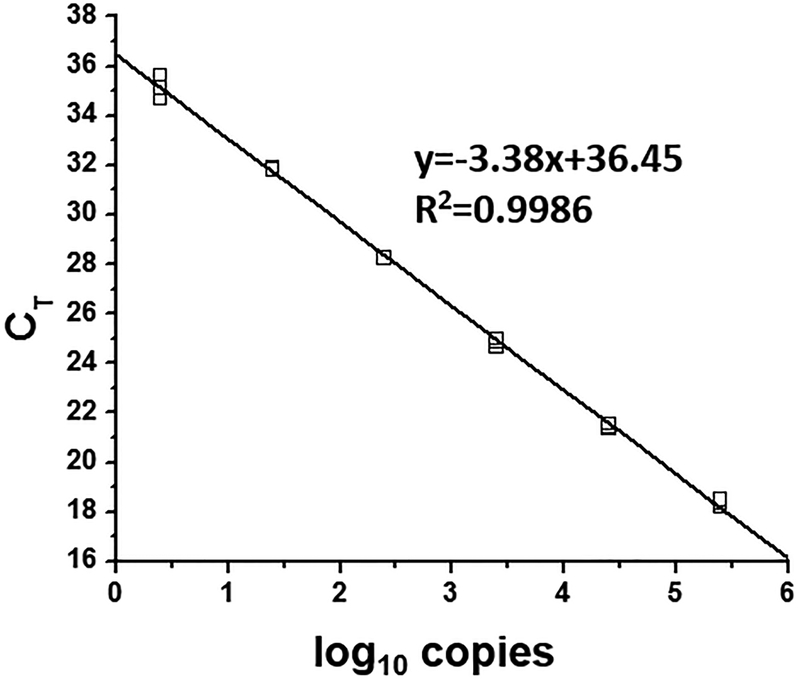

4. The standard curve is generated by plotting the CT vs. the log10 copies of serially diluted plasmid harboring Cβ and Vβ genes (2.5 – 2.5 × 105 copies). The slope, intercept, and correlation coefficiency (R2) are determined using Microcal OriginPro Vesion 7.5 (OriginLab) (see Note 5).

Representative standard curve for the Cβ gene is shown in Figure 1. Standard curves for the Cβ and Vβ genes are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

A representative standard curve generated for the Cβ gene, reproduced from [12] with permission from JTM. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using 10-fold serially diluted templates (2.5 – 2.5 × 105 copies). The CT was determined and plotted over the log10 copies to calculate the slope, Y axis intercept, and correlation coefficiency (R2).

Table 2.

Standard curve slopes, Y axis intercepts and correlation coefficients (R2), reproduced from [12] with permission from JTM.

| Primers | Slope | Y axis intercept | Correlation coefficient (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cβ | −3.38 | 36.45 | 0.9986 |

| VB1 | −3.39 | 36.54 | 0.9977 |

| VB2 | −3.36 | 36.38 | 0.9982 |

| VB3 | −3.41 | 36.57 | 0.9987 |

| VB4 | −3.37 | 36.62 | 0.9984 |

| VB5 | −3.35 | 36.33 | 0.9976 |

| VB6 | −3.40 | 36.53 | 0.9978 |

| VB7 | −3.36 | 36.43 | 0.9983 |

| VB8 | −3.37 | 36.40 | 0.9986 |

| VB9 | −3.38 | 36.49 | 0.9985 |

| VB11 | −3.41 | 36.52 | 0.9986 |

| VB12 | −3.42 | 36.53 | 0.9972 |

| VB13A | −3.34 | 36.34 | 0.9978 |

| VB13B | −3.41 | 36.54 | 0.9974 |

| VB14 | −3.36 | 36.33 | 0.9981 |

| VB15 | −3.35 | 36.44 | 0.9976 |

| VB16 | −3.37 | 36.44 | 0.9984 |

| VB17 | −3.39 | 36.53 | 0.9982 |

| VB18 | −3.35 | 36.44 | 0.9986 |

| VB20 | −3.33 | 36.39 | 0.9973 |

| VB21 | −3.36 | 36.38 | 0.9986 |

| VB22 | −3.39 | 36.47 | 0.9981 |

| VB23 | −3.37 | 36.43 | 0.9980 |

| VB24 | −3.41 | 36.53 | 0.9984 |

3.5.2. Quantification of Vβ gene

1. Set up triplicate qRT-PCR reactions (25 μl) consisted of:

12.5 μl Power SYBR Green PCR Master mix

5 μl 2 pmoles forward and reverse primers (2.5 μl each) specific to the Cβ or Vβ gene

5 μl cDNA prepared in 3.3

2.5 μl DNase-free water

2. Perform and analyze the qRT-PCR as described in 3.5.1 (see Note 4).

3. For absolute quantification, the absolute copy numbers of the Cβ or Vβ gene is calculated by extrapolating the CT to the standard curve listed in Table 2 (see Note 6).

4. The percentage of each Vβ (%Vβ) is calculated by the following equation:

Where:

%Vβn= the percentage of indicated (n) Vβ group

Vβn= the copy number of indicated (n) Vβ group

Cβ= the copy number of Cβ gene

5. Selective expansion of Vβ by SAg is determined when the %Vβn from the culture stimulated with SAg is significantly higher than the corresponding %Vβn from the unstimulated culture (without stimuli) by paired t-test (p<0.01).

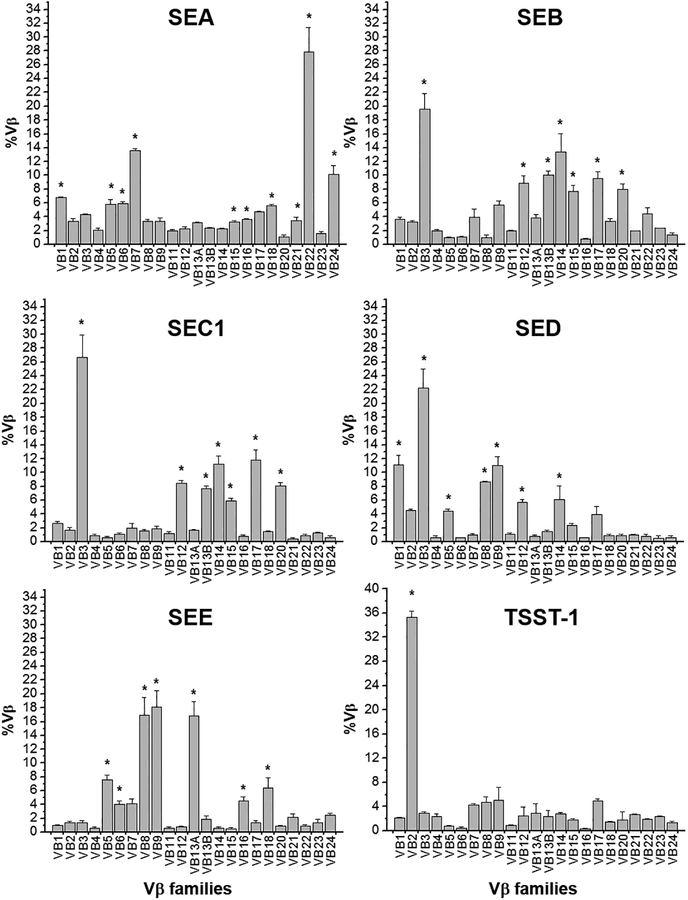

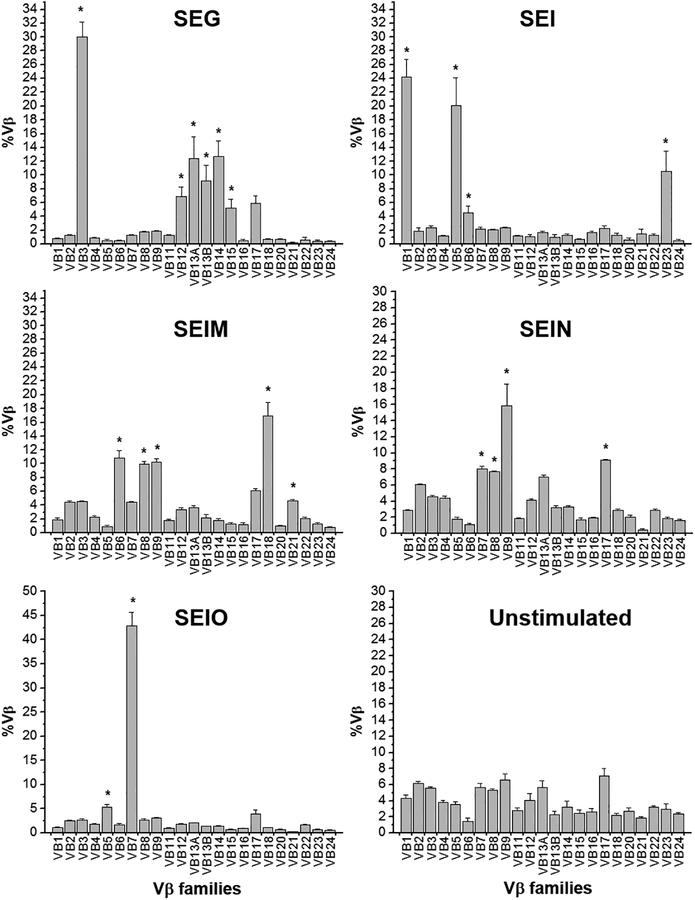

The established method was applied to determine the Vβ specificity of SEA, SEB, SEC1, SED, SEE, SEG, SEI, SElM, SElN, SElO, and TSST-1. Results are summarized in Figure 2 and Table 3 and showed accurate, reproducible, and comparable results observed in previous studies [15–17]

Figure 2.

Selective expansion of TCR Vβ by SAgs, reproduced from [12] with permission from JTM. Enriched human lymphocytes were stimulated with an indicated SAg (0.5 μg/ml) for 4 days. Quantitative real time PCR was performed and the %Vβ was calculated. Selective expansion of Vβ by SAg is determined when the %Vβn from the culture stimulated with SAg is significantly higher than the corresponding %Vβn from the unstimulated culture (without stimuli) by paired t-test. The asterisk indicates a statistically significance (p<0.01).

Table 3.

Summary of Vβ specificity observed with this methods and comparison with those in selected previous studies, reproduced from [12] with permission from JTM.

| SAgs | Vβ specificity observed in this study | Vβ specificity observed in previous studiesa | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEA | Vβ1, 5, 6, 7, 15, 16, 18, 21, 22, 24 | Vβ1, 5, 6, 7, 9, 16, 18, 21 | [15] |

| SEB | Vβ3, 12, 13Bb, 14, 15, 17, 20 | Vβ1, 3, 6, 12, 13.2, 15, 17, 20 | [16] |

| SEC1 | Vβ3, 12, 13B, 14, 15, 17, 20 | Vβ3, 12, 13.2, 14, 15, 17, 20 | [9] |

| SED | Vβ1, 3, 5, 8, 9, 12, 14 | Vβ1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12 | [18,7] |

| SEE | Vβ5, 6, 8, 9, 13Ac, 16, 18 | Vβ5, 6, 8, 13.1, 18, 21 | [15,16] |

| SEG | Vβ3, 12, 13A, 13B, 14, 15 | Vβ3, 12, 13, 14 | [17] |

| SEI | Vβ1, 5, 6, 23 | Vβ1, 5, 6, 23 | [17] |

| SElM | Vβ6, 8, 9, 18, 21 | Vβ6, 8, 9, 18, 21 | [17] |

| SElN | Vβ7, 8, 9, 17 | Vβ9 | [17] |

| SElO | Vβ5, 7 | Vβ5, 7, 22 | [17] |

| TSST-1 | Vβ2 | Vβ2 | [16] |

Vβ specificities were results from previous studies using semi-quantitative PCR or FACS methods.

Vβ13B corresponds to Vβ13.2 in previous studies.

Vβ13A corresponds to Vβ13.1 in previous studies.

4. Notes

If the cell pellet is contaminated with red blood cells, resuspend the cell pellet in 1×ACK lysis buffer (Life technologies, add 1 ml 1 × ACK lysis buffer per 2 ml of original blood volume), incubate at room temperature for 5 min, and add equal volume of PBS.

The cell pellet or lysate can be stored in – 80°C for a month. Frozen samples should be completely thawed and continue with step 3.

Normally, we do not experience DNA contamination in the RNA preparation after the DNase I treatment. A contamination of DNA in RNA preparation could be verified by PCR reactions with primers specific to GAPDH (forward: 5’-GCAAATTCCATGGCACCGT-3’; reverse: 5’-TCGCCCCACTTGATTTTGG-3’).

Melting curve analysis of primers for Vβ7, 12, 13A, and 17 may show multiple peaks due to the amplification of multiple Vβ subgroup genes that have heterogeneity in melting temperature. Although primers for Vβ5, 6 13B, and 21 also amplify multiple Vβ subgroup genes, melting curve analysis showed a single peak due the homogeneity in melting temperatures.

Standard curves generated for Cβ and Vβ genes using other real time PCR equipment such as iCycler (Bio-rad) was not significantly different from those generated by ABI 7500 real-time PCR systems.

To synchronize real-time PCR data analysis, the base line signal and threshold was set to be determined automatically by the Sequence Detector System version 1.2.2.

References

- 1.Davis MM, Boniface JJ, Reich Z, Lyons D, Hampl J, Arden B, Chien Y (1998) Ligand recognition by alpha beta T cell receptors. Annu Rev Immunol 16:523–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowen L, Koop BF, Hood L (1996) The complete 685-kilobase DNA sequence of the human beta T cell receptor locus. Science 272 (5269):1755–1762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis MM, Bjorkman PJ (1988) T-cell antigen receptor genes and T-cell recognition. Nature 334 (6181):395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behlke MA, Spinella DG, Chou HS, Sha W, Hartl DL, Loh DY (1985) T-cell receptor beta-chain expression: dependence on relatively few variable region genes. Science 229 (4713):566–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lefranc M, Lefranc G (2001) The T cell receptor. Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arden B, Clark SP, Kabelitz D, Mak TW (1995) Human T-cell receptor variable gene segment families. Immunogenetics 42 (6):455–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seo KS, Bohach GA (2007) Staphylcoccus aureus In: Doyle MM, Beucaht LR (eds) Food microbiology: Fundamentals and Frontiers. 3rd edn ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp 493–518 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohach GA (2006) Staphylococcus aureus Exotoxins In: Fischetti VA, Novick RP, Ferretti JJ, Portnoy DA, Rood JI (eds) Gram-Positive Pathogens. 2nd edn ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp 464–477 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deringer JR, Ely RJ, Stauffacher CV, Bohach GA (1996) Subtype-specific interactions of type C staphylococcal enterotoxins with the T-cell receptor. Mol Microbiol 22 (3):523–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pilch H, Hohn H, Freitag K, Neukirch C, Necker A, Haddad P, Tanner B, Knapstein PG, Maeurer MJ (2002) Improved assessment of T-cell receptor (TCR) VB repertoire in clinical specimens: combination of TCR-CDR3 spectratyping with flow cytometry-based TCR VB frequency analysis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 9 (2):257–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bercovici N, Duffour MT, Agrawal S, Salcedo M, Abastado JP (2000) New methods for assessing T-cell responses. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 7 (6):859–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seo KS, Park JY, Terman DS, Bohach GA (2010) A quantitative real time PCR method to analyze T cell receptor Vbeta subgroup expansion by staphylococcal superantigens. Journal of translational medicine 8:2. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) Concentration of DNA Solution In: Nolan C (ed) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd edn Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, p Appendix C1 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin JL, Shackel NA, Zekry A, McGuinness PH, Richards C, Putten KV, McCaughan GW, Eris JM, Bishop GA (2001) Real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for measurement of cytokine and growth factor mRNA expression with fluorogenic probes or SYBR Green I. Immunol Cell Biol 79 (3):213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamphear JG, Mollick JA, Reda KB, Rich RR (1996) Residues near the amino and carboxyl termini of staphylococcal enterotoxin E independently mediate TCR V beta-specific interactions. J Immunol 156 (6):2178–2185 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi YW, Kotzin B, Herron L, Callahan J, Marrack P, Kappler J (1989) Interaction of Staphylococcus aureus toxin “superantigens” with human T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86 (22):8941–8945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarraud S, Peyrat MA, Lim A, Tristan A, Bes M, Mougel C, Etienne J, Vandenesch F, Bonneville M, Lina G (2001) egc, a highly prevalent operon of enterotoxin gene, forms a putative nursery of superantigens in Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol 166 (1):669–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kappler J, Kotzin B, Herron L, Gelfand EW, Bigler RD, Boylston A, Carrel S, Posnett DN, Choi Y, Marrack P (1989) V beta-specific stimulation of human T cells by staphylococcal toxins. Science 244 (4906):811–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]