Abstract

Objective:

Maternal infection during pregnancy has been associated with increased risk of offspring psychopathology, including depression. As most infections do not cross the placenta, maternal immune responses to infection have been considered as potentially contributing to this relationship. This study examined whether gestational timing of maternal inflammation during pregnancy is associated with offspring internalizing and/or externalizing symptoms during childhood and, further, whether fetal sex moderated this relationship.

Method:

Participants were 737 pregnant women and their offspring who were continuously followed through late childhood. Archived first and second trimester sera were analyzed for markers of inflammation [interleukin 8 (IL-8), IL-6, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-II (sTNF-RII)]. When offspring were aged 9–11, mothers completed a questionnaire assessing psychological symptoms.

Results:

Multivariate regression analyses indicated that elevated IL-8 in the first trimester was associated with significantly higher levels of externalizing symptoms in offspring. Higher IL-1ra in the second trimester was associated with higher offspring internalizing symptoms. Further, second trimester IL-1ra was associated with increased internalizing symptoms in females only.

Conclusion:

These findings demonstrate that elevated maternal inflammation during pregnancy is associated with the emergence of separate psychological phenotypes and that timing of exposure and fetal sex matter for offspring outcomes. Given that internalizing and externalizing symptoms in childhood increase risk for a variety of mental disorders later in development, these findings potentially have major implications for early intervention and prevention work.

Keywords: Maternal inflammation during pregnancy, conduct problems, anxiety, depression, Children

Introduction

Childhood internalizing (e.g., withdrawal, sorrow, and worry) and/or externalizing symptoms (e.g. aggression, impulsivity) increase risk for later psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, substance use disorders, and schizophrenia) (Cicchetti and Toth, 1991). Antenatal maternal factors (e.g., malnutrition, distress, toxin exposure) are associated with the emergence of childhood internalizing and externalizing symptoms (MacKinnon et al., 2017) as well as later psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia and depression (Allen et al., 1998). While there is growing evidence that one antenatal maternal factor, maternal inflammation during pregnancy (MIP), is associated with subsequent psychiatric conditions in offspring (e.g. schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism), less is known about the role of MIP in the emergence of childhood internalizing and externalizing phenotypes (Depino, 2018). Since internalizing and externalizing symptoms in childhood increase risk for a variety of mental disorders later in development, understanding the role of maternal inflammation in the emergence of internalizing and externalizing symptoms is important for early identification and prevention.

There is compelling evidence linking maternal exposure to infection during pregnancy with adverse psychiatric outcomes in their offspring (Brown and Derkits, 2009; Machón et al., 1997; Murphy et al., 2017). It is likely that the maternal inflammatory responses following exposure to infection is the mechanism by which risk is conferred to the offspring, since some inflammatory cytokines can cross the placenta (Shi et al., 2005) while the majority of viral/bacterial pathogens cannot (Fineberg and Ellman, 2013). In support of this hypothesis, multiple studies using direct assessment of inflammatory activation have linked maternal inflammation with greater likelihood of offspring psychiatric diagnoses of schizophrenia (Brown et al., 2004; Fineberg and Ellman, 2013), autism (Brown et al., 2014), bipolar disorder (Canetta et al., 2014), and major depressive disorder (Gilman et al., 2016). Although internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children as well as elevated maternal inflammation are both predictors of serious psychiatric disorders, it remains unclear whether increased levels of MIP is predictive of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children. Only one human study has investigating the role of MIP in childhood behavior, which found that elevated interleukin-6 (IL-6) during pregnancy predicted worse impulse control in two year old offspring via differential amygdala development (Graham et al., 2018). Thus, there is strong reason to believe that MIP is associated with internalizing and externalizing behaviors in offspring.

Animal research provides additional evidence that MIP is associated with the development of internalizing and externalizing behaviors in offspring. Animals exposed to MIP are more likely to exhibit behaviors (e.g. decreased exploration, anhedonia, increased threat sensitivity, cognition, and sensitivity to stimulants) that are analogues of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in humans (Meyer et al., 2009; Simanek and Meier, 2015). Moreover, animal studies suggest that the inconsistent results observed in human studies may, in part, be attributable to the differential effect of MIP by fetal sex and the trimester during which inflammation occurs (Meyer, 2014). Animal studies report a generalized pattern of differential timing of MIP (trimester one (T1) vs. trimester two (T2)) impacting different stages of fetal neurodevelopment, leading to animal offspring phenotypes similar to internalizing and externalizing symptoms in humans (Meyer et al., 2006). In rodents, T1 MIP is associated with sensorimotor gating, associative learning difficulties and sensitivity to amphetamine use-animal behaviors similar to an externalizing phenotype in humans (Krueger et al., 2002). This cluster of trimester one deficits may be related to alterations in the dopamine system caused by MIP (e.g., prefrontal hypoactivation and subcortical hyperactivation in dopamine receptor D1; Meehan et al., 2017). Conversely, T2 MIP is associated with deficits in social interactions, anhedonic behavior, as well as perseverative behaviors and cognitive inflexibility in rodent offspring (Babri et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2012), behaviors similar to internalizing behaviors in humans.

There is also good evidence that the effects of MIP may be dependent upon the sex of the fetus (for a review see (Rana et al., 2012)), however this research question is relatively understudied (Boksa, 2010). First, there are robust sex differences in the prevalence of psychological disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, autism, depression). Second, both human and rodent research have shown that negative behavioral and cognitive outcomes (e.g., depressive and anxious behaviors) following prenatal infection/inflammation is dependent on fetal sex (Gilman et al., 2016; Rana et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2010). The precise relationship between fetal sex and neurodevelopmental outcomes is unclear because of a strong bias in animal research towards the experiments that use male animals only (Beery and Zucker, 2011) and because there are multiple additional factors moderating the relationship between MIP and behavioral outcomes (e.g., the dose and character of immune response as well as the timing of administration during gestations). However, give the elevated prevalence of internalizing disorders in females and the heightened risk of conduct disorders in males (Zahn-Waxler et al., 2008), it is probable that MIP confers a similar risk profile.

The Present Study

The present study will test whether the timing of MIP, as measured by levels of inflammatory biomarkers in maternal sera, differentially predicts internalizing and externalizing symptoms in offspring. Data are based on maternal report via questionnaire of the offspring’s symptoms at a 9–11 year follow-up obtained from a large-scale, longitudinal study, and immunoassays performed on archived maternal serum obtained during T1 and T2 of pregnancy. This study hypothesizes that:

Elevated T1 MIP predicts more severe offspring externalizing symptoms.

Elevated T2 MIP predicts more severe offspring internalizing symptoms.

An exploratory aim is to test whether the relationship between MIP and internalizing and externalizing symptoms in offspring will differ by sex.

Method

Participants

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at two large universities in the United States. Participants were drawn from a prospective, longitudinal study of women that gave birth in a socio-economically and racially diverse county in the United States between 1959 and 1966, resulting in 19,044 live births. The prospective, longitudinal study recruited virtually all pregnant women seeking obstetric care within this diverse county of the United States (van den Berg et al., 1988). Live births from 1960–1963 (n=9,708) were the basis for childhood follow-up studies.

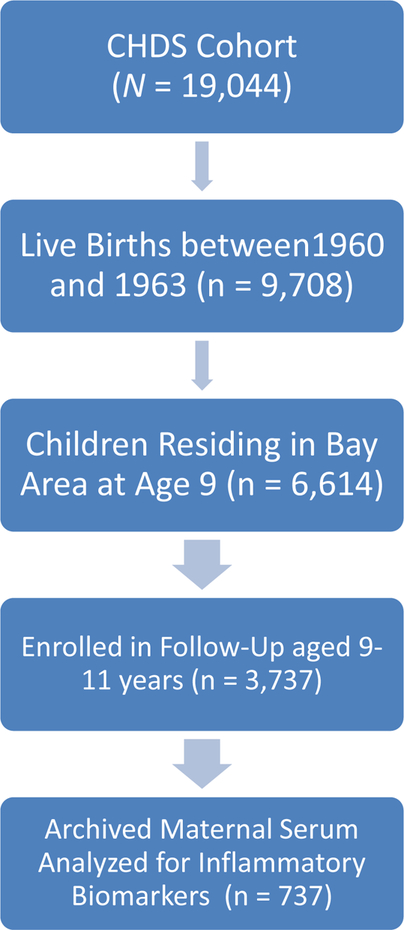

Among children in these birth cohorts still residing in the county at age 9 (n=6,614), 3,737 were enrolled in the follow-up at ages 9–11 years. Mother/offspring pairs were included in the current analyses for 737 mothers for whom archived maternal serum samples from T1 and/or T2 were available for immunoassay, with 1,304 sera samples available in total. See Figure 1 for details.

Figure 1.

The Number of Participants Recruited and Retained for the Child Health and Development Studies in Addition to the Number of Mothers Whose Serum was Assayed

Measures

Demographic Variables

Demographic data were gathered from maternal interviews during pregnancy. Maternal education was categorized as ‘Did not complete High School’, ‘Completed High School’ or ‘Completed more than High School’; maternal education is used as a proxy for socio-economic status, since this variable is correlated with other measures of SES (e.g., income) in similar studies (Fineberg et al., 2016) and is frequently used as a proxy for postnatal adversity (Schlotz and Phillips, 2009). Race was categorized as: ‘White’ vs. ‘Non-white’; with the ‘Non-white’ sub-sample composed of ‘African-American’ (20.2%) and ‘Asian’ (5.6%). Offspring sex was categorized as ‘Male’ or ‘Female’.

Maternal Report of Offspring Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms

During the follow-up exam (mean child age=9.71, SD=.71), mothers answered ‘true’, ‘not true,’ or ‘uncertain’ to 100 questions about their child’s behavior; items were adapted to simplify vocabulary so that parents could easily respond. Internalizing and externalizing items were selected based on their similarity to items measuring these constructs in the Child Behavior Checklist, a well-validated measure of psychopathology in children (Achenbach, 1991).

The inclusion of ‘uncertain’ responses in the questionnaire represented a significant methodological problem since it was unclear whether the respondents were: uncertain as to the meaning of the question, uncertain as to whether their child’s behavior met criteria outlined by the question, or uncertain for another reason. Further, total number of ‘uncertain’ responses was significantly associated with maternal self-reported worries at the time of maternal interview, r(637)=.137, p=.001, but not with education or race. This indicates that there is significant variability in the probability of responding uncertainly which is based on at least one maternal characteristic known to be associated with maternal inflammation and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Further, it is probable that responses are additionally attributable to unknown maternal characteristics. Consequently, it is inappropriate to treat ‘uncertain’ responses as missing data, given strong evidence that data are not ‘missing not at random (Graham, 2009). Thus, ‘uncertain’ responses on either the internalizing or externalizing scale were removed. Given the challenge of working with the original questionnaire data, additional analyses are included in the supplementary material (i) comparing the analytic and excluded samples, (ii) presenting an exploratory factor analysis confirming a satisfactory two factor solution for internalizing/externalizing questionnaire items, and (iii) replicating results using a less conservative approach to handling “uncertain” responses which increases the statistical power of the analyses – see supplementary information for complete details. In brief, these analyses indicate that no systematic differences are observable when comparing the analytic to the excluded sample, that two latent internalizing and externalizing factors underpin questionnaire data, and that findings from the results presented in this manuscript conceptually replicate when a more liberal approach to “uncertain “ responses are used.

Internalizing symptoms were estimated using 13 items from the 100-item questionnaire described above. Item examples include: ‘Often seems tired’, ‘Has lots of fears and worries’, ‘Shy, bashful’, and ‘Often in dumps, blue’. Only ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ responses were considered valid responses and internalizing scores only were calculated for those with valid responses on all 13 items. On average, girls were reported to have 2.90 internalizing symptoms (SD = 2.47) while boys were reported to have 2.64 symptoms (SD = 2.17). For the 315 individuals with complete data on the internalizing scale, the scale demonstrated adequate reliability with a Cronbach’s Alpha of .704.

Fifteen items, including ‘Stays away from home without permission’, ‘Spoils or breaks things belonging to others’, ‘Sassy, talks back when told to do anything’, and ‘Bullies others’, were used to assess externalizing symptoms. Only ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ responses were considered valid responses and externalizing scores only were calculated for those with valid responses on all 15 items. On average, girls were reported to have 1.99 externalizing symptoms (SD = 1.97) while boys were reported to have 2.54 symptoms (SD = 2.32). For the 311 individuals with complete data, the scale demonstrated adequate reliability with a Cronbach’s Alpha of .714. Both of these scales have been used in studies examining the relationship between maternal risk factors during pregnancy and behavioral outcomes in offspring (Maxwell et al., 2018).

Maternal Worries and Psychiatric Diagnoses

Maternal interviews when the child was aged 9–11 assessed financial, marital, employment or health worries endorsed by the mother about herself; this measure of maternal worry has been used previously in similar studies (Maxwell et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2017). For each item, a ‘Yes’ response was coded as a score of one and a ‘No’ response as zero, with total scores ranging from zero to four. Additionally, the current study examined data from maternal medical charts for the first and second trimesters of pregnancy. During this period, a range of diagnoses were included in the medical charts that related loosely to disorders involving psychosis (e.g., schizophrenia), anxiety (e.g., Anxiety without somatic symptoms), and emotional disturbances (e.g., Neurasthenia). From the entire sample of 737 mothers, one gravida had a psychotic diagnosis during trimester one and two of pregnancy, 16 met criteria for anxious disorders, and 13 met criteria for a diagnosis involving an emotional disturbance in the first trimester while six met criteria during the second trimester.

Maternal Inflammation during Pregnancy

During T1 and T2, 12cc of blood were drawn from mothers in each trimester; assays were conducted on archived prenatal sera of 737 mothers. All assays were conducted in the inflammatory biology laboratory of a large public university. The cytokines IL-6 and IL-8, the soluble receptor for TNF-α (sTNF-RII), and the receptor antagonist for IL-1β (IL-1ra) were assayed using Quantikine High Sensitivity human IL-6 and IL-8 ELISA kits and regular sensitivity ELISA kits for the other markers (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). sTNF-rII and IL-1ra are valid and reliable estimates of TNF-α and IL-1β activity that are present at much higher concentrations in sera than the cytokines themselves, thus allowing for consistently detectable values of cytokine activity in a pregnancy population characterized by suppressed immune function (Diez-Ruiz et al., 1995; Irwin et al., 2007). Assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols with the following exceptions: sera were routinely tested at a 5-or 25-fold dilution for IL-8, and at a 30-fold dilution for sTNF-rII; samples outside the range of the reference standard curve were re-assayed at an appropriate dilution. IL-6 and IL-8 assays were given priority for those archival specimens with insufficient volume for all analytes. Samples from T1 and T2 from the same woman were always assayed together on the same assay plate, to minimize differences between gestational timing that might have been introduced from interassay variation. Paired samples for each pregnancy were randomly assigned to an assay plate, and randomly ordered within plates. Every assay plate contained an internal quality control sample, with inter-assay correlation coefficients <9% and mean intra-assay correlation coefficients <4% for all analytes.

Data Analysis

Bivariate correlations between the dependent variables, inflammatory biomarkers and demographic variables, as well as maternal variables (age of gravida at birth, maternal race, and maternal worries) were examined. All biomarkers were log-transformed. Variables significantly correlated with at least one of the outcomes and at least one inflammatory biomarker were included as covariates (e.g., sex, race and maternal education). Multivariate regression was conducted using IBM SPSS (v24), with each inflammatory biomarker predicting to internalizing and externalizing symptoms in separate models when controlling for covariates. Interaction terms were based on mean-centered predictor variables and significant interactions are visually presented as one standard deviation below the mean (Low), at the mean (Moderate), and one standard deviation above the mean (High). Simple slope analyses are reported that indicate whether the association of the predictor and the outcome variable differs from zero at a given value of the moderator (e.g., sex).

Results

From the 737 mothers for whom archived sera was assayed for biomarkers of inflammation, 405 had biomarker data at T1 and/or T2, and had complete offspring data on either the internalizing or externalizing scales. No differences were observed between the analytic (n=405) and excluded (n=332) mothers on demographic, maternal health, or inflammatory biomarker variables (see supplementary material). A correlation matrix and descriptive statistics (final two rows) are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations of Study Variables (N = 405)

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Int | − | .38*** | −.09 | −.14* | .11* | −.07 | .03 | −.09 | .04 | .10 | .13* | −.02 | .05 | .11 | −.06 |

| 2: Ext | − | .05 | −.09 | .20*** | −.14* | .03 | −.03 | .16** | .12* | .07 | −.02 | −.04 | .10 | .13* | |

| 3: Grav Age | − | −.16** | .08 | .02 | .00 | .02 | −.04 | .05 | −.09 | − 04 | .00 | .01 | .00 | ||

| 4: Race(White) | − | −.12* | .11* | .06 | .11* | .09 | −.05 | .09 | .18** | .11* | −.05 | −.07 | |||

| 5: Worries | − | −.03 | −.08 | −.04 | −.09 | −.08 | −.09 | .02 | −.01 | .02 | −.03 | ||||

| 6: Gravida Education | − | −.04 | −.02 | −.01 | −.06 | −.17** | .01 | −.04 | −.16** | −.02 | |||||

| 7: T1-IL1ra | − | .39*** | .28*** | .40*** | 37*** | .17** | .01 | .02 | .01 | ||||||

| 8: T1-TNF | − | .21*** | .27*** | .24*** | .51*** | .04 | .09 | .02 | |||||||

| 9: T1-IL8 | − | .51*** | .04 | .09 | .15* | .04 | .00 | ||||||||

| 10: T1-IL6 | − | .03 | .02 | .06 | .15* | .01 | |||||||||

| 11: T2-IL1ra | − | .39*** | .41*** | .47*** | .02 | ||||||||||

| 12: T2-TNF | − | .20*** | .25*** | .05 | |||||||||||

| 13: T2-IL8 | − | .53*** | −.08 | ||||||||||||

| 14: T2: IL-6 | .01 | ||||||||||||||

| 15: Sex | − | ||||||||||||||

| Mean | 2.77 | 2.26 | 28.92 | .75 | .22 | 2.44 | 6.22 | 7.88 | 5.80 | .51 | 6.15 | 8.03 | 5.69 | .39 | .51 |

| (SD) | 2.32 | 2.16 | 5.76 | .43 | .52 | .65 | .61 | .25 | 1.68 | .95 | .50 | .23 | 1.68 | .84 | .50 |

Note: Int: Internalizing Behaviors; Ext: Externalizing Behaviors; T1 = Trimester 1; T2 = Trimester 2; Grav Age = Age of Gravida; Race Reference Category is Non-White; IL1ra = IL-1 receptor antagonist; TNF = Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha; TNF alpha estimated using soluble TNF receptor two. Probability:

p<.05

p<.01

<.001

Bivariate Correlations

A significant positive association was observed between offspring internalizing symptoms at ages 9–11 and T2 IL-1ra. Further, significant positive associations were observed between externalizing symptoms and T1 IL-8 and T1 IL-6. Maternal race was significantly negatively associated with internalizing symptoms, so that those identifying as white reported fewer internalizing symptoms among offspring. Positive associations were observed between maternal race and multiple inflammatory cytokines. Maternal worries were significantly associated with both offspring internalizing and externalizing symptoms; however, no significant relationship was observable between maternal worries and any of the inflammatory cytokines. Maternal education was significantly associated with offspring externalizing symptoms, such that higher education was associated with lower externalizing symptomatology. Maternal education also was associated with lower levels of maternal T2 IL-6 and T2 IL-1ra. Being male was associated with higher levels of externalizing symptoms. Race and maternal education were controlled for given their association with a dependent variable, in addition to markers of cytokine activity. Sex was included as a covariate given the strong a priori rationale for its inclusion and the objective of testing for sex-based interactions.

Multivariable Regression

Multivariable regression analyses predicting to internalizing and externalizing symptoms are reported in Table 2. Unadjusted univariate associations are reported in the far right columns of Table 2.

Table 2.

Regression Models Predicting Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms For (i) Four Cytokine Values Across Two Trimesters Adjusted For Sex, Race and Maternal Education and (ii) Interaction of Sex by Cytokine; Univariate Regression For Each Variable Predicting Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms Are Also Presented to the Right of the Table.

| Internalizing Symptoms | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trimester 1 Models b(SE)p | Trimester 2 Models b(SE)p | Univariate Regression | ||||||||

| (i) Eight Models For Four Cytokine Values Across Two Trimesters That Have Been Adjusted For Sex, Race and Maternal Education | Predictor | b(SE)p | ||||||||

| Predictors | IL-1ra | sTNF-RII | IL-8 | IL-6 | IL-1ra | sTNF-RII | IL-8 | IL-6 | Race (White) | −.15(.26)** |

| Cytokine1 | .04(.2 4) | −.08(.58) | .06(.08) | .09(.16) | .14(.29)* | −.01(.64) | .06(.08) | .10(.16)a | Maternal Ed. | −.06(.24) |

| R2 | 4.1% | 4.5% | 3.4% | 3.9% | 3.6% | 1.8% | 3.0% | 3.7% | Sex (Male) | −.06(.26) |

| (ii) Addition of Sex Interaction to above multivariate models | T1 IL-1ra | −.06(.26) | ||||||||

| Cytokine*Sex | −.02(.47) | .88(1.16) | .30(.17) | .12(.33) | − 1.93(.57)* | .81(1.27) | .10(.17) | .14(.33) | T1 sTNF-RII | −.09(.58) |

| R2 | 4.1% | 4.6% | 4.0% | 4.3% | 6.0% | 1.9% | 3.1% | 4.5% | T1 IL-8 | .04(.08) |

| T1 IL-6 | .10(.16)a | |||||||||

| T2 IL-1ra | .13(.29)* | |||||||||

| T2 sTNF-RII | −.02(.63) | |||||||||

| T2 IL-8 | .05(.08) | |||||||||

| T2 IL-6 | .11(.16)a | |||||||||

| Externalizing Symptoms | ||||||||||

| Trimester 1 Models b(SE)p | Trimester 1 Models b(SE)p | Univariate Regression | ||||||||

| (i) Eight Models For Four Cytokine Values Across Two Trimesters That Have Been Adjusted For Sex, Race and Maternal Education | Predictor | b(SE)p | ||||||||

| Predictors | IL-1ra | sTNF-RII | IL-8 | IL-6 | IL-1ra | sTNF-RII | IL-8 | IL-6 | Race (White) | −.10(.28)a |

| Cytokine1 | .04(.22) | −.03(.54) | .17(.08)** | .10(.13)a | .06(.28) | −.02(.64) | −.04(.08) | .06(.15) | Maternal Ed. | −.14(.18)* |

| R2 | 4.3% | 4.2% | 7.0% | 5.2% | 4.3% | 4.1% | 5.0% | 5.3% | Sex (Male) | −.06(.26) |

| (ii) Addition of Sex Interaction to above multivariate models | T1 IL-1ra | −.06(.26) | ||||||||

| Cytokine*Sex | .30(.44) | 2.59(1.10) | .08(.15) | .19(.26)a | −.35(.55) | 4.28(1.26)a | −.16(.16) | .07(.31) | T1 sTNF-RII | −.03(.54) |

| R2 | 4.4% | 4.9% | 7.0% | 6.5% | 4.4% | 5.4% | 5.2% | 5.5% | T1 IL-8 | .16(.08)** |

| T1 IL-6 | .12(.13)* | |||||||||

| T2 IL-1ra | .07(.28) | |||||||||

| T2 sTNF-RII | −.02(.64) | |||||||||

| T2 IL-8 | −.04(.08) | |||||||||

| T2 IL-6 | .10(.15) | |||||||||

Probability:

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

Cytokine1 = Cytokine referenced as title of each Trimester Model; T1 = Trimester 1; T2 = Trimester 2; Ed. = Education; Univariate Regression = Presents parameter estimates of univariate regression of the predictor to the outcome. TNF-α estimated using soluble TNF receptor two and IL-1 β using IL-1 receptor antagonist.

Internalizing Symptoms

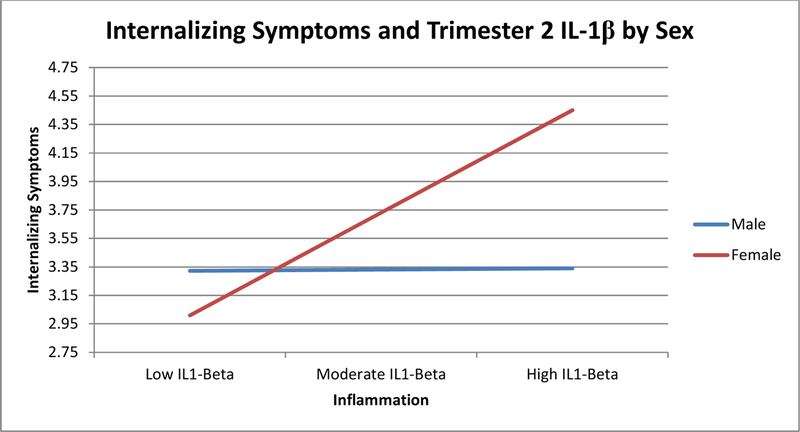

Higher levels of T2 IL-1ra were significantly associated with higher levels of internalizing symptoms in offspring (see Table 2). Likewise, an association that approached significance was observed for higher T2 IL-6 with higher offspring internalizing symptoms. Additionally, the association between IL-1ra and internalizing symptoms was moderated by offspring sex, so that only female offspring experienced significantly higher levels of internalizing symptoms following exposure to T2 IL-1ra, see Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Moderation Analysis Examining the Relationship between Trimester Two Levels of Maternal Receptor Antagonist for Interleukin-1β and Offspring Internalizing Symptoms

Externalizing Symptoms

Higher levels of maternal T1 IL-8 were significantly associated with externalizing symptoms, while higher levels of maternal T1 IL-6 approached significance in their association with higher levels of offspring externalizing symptoms. Further, an interaction was observed (that approached significance) such that males exhibited excess levels of externalizing symptoms when exposed to equivalent levels of maternal T1 IL-6.

Significant associations between control variables and both internalizing and externalizing symptoms are presented in (see Table S1, available online).

Discussion

This is the first human study to demonstrate that maternal inflammation during pregnancy is associated with subsequent internalizing and externalizing symptoms in offspring aged 9–11 years. Higher levels of T2 IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) were associated with more internalizing symptoms in females while higher levels of T1 IL-8 predicted higher levels of subsequent conduct problems among offspring. This is the first study to suggest that the timing of exposure to MIP and fetal sex are important in determining risk to offspring. Further, our findings suggests that inconsistent results observed across studies examining maternal infection and maternal inflammation may be due to the moderating impact of fetal sex and the timing of inflammation.

The observed association between T1 MIP and externalizing symptoms supports animal research linking T1 MIP during pregnancy with animal analogues of human externalizing symptoms (e.g., sensorimotor gating deficits/worse associative learning/sensitivity to amphetamine use; Meyer, 2014; Meyer et al., 2009). Additionally, these results are in line with human research linking T1 maternal infection to subsequent externalizing symptoms in children (MacKinnon et al., 2017). T2 MIP was found to be associated with offspring internalizing symptoms. While many animal studies report that internalizing symptoms is associated with MIP independently of timing (Boksa, 2010; Depino, 2015), other animal (Bauman et al., 2014) and human (Murphy et al., 2017; Simanek and Meier, 2015) studies report a specific link between T2 MIP or maternal infection and internalizing symptoms. When considered as a whole, these findings support a relatively consistent general finding from the animal literature that the exact timing of MIP fundamentally influences the type of behavioral abnormalities observed in the offspring (Meyer, 2014; Meyer et al., 2006).

In the current study, females were more likely to exhibit elevated internalizing symptoms following T2 IL-1 exposure. Understanding sex differences in MIP matters, given sex-based susceptibility to internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Zahn-Waxler et al., 2008). Animal (Rana et al., 2012) and human (Gilman et al., 2016; Machón et al., 1997; Mino et al., 2000; Morgan et al., 1997) studies report mixed results, with fetal sex conferring both risk and protection. The sex-dependent differences observed in these results are, more generally, in line with the recognized sex-specific effect that a diverse range of environmental factors have on placental functions and the risk of disease later in the lifespan (Gabory et al., 2013). Inconsistent results likely reflect, in part, the complex interplay between genetic predispositions to psychiatric conditions, sex, the timing of maternal inflammation during pregnancy, potentially unobserved environmental risk factors that occur in early childhood as well as differences between onset of internalizing symptoms in childhood and diagnostic criteria in adulthood (Simanek and Meier, 2015). It is also likely that inconsistencies across human and animal research is caused, in part, by differential, sex-specific responses of biological systems (e.g., stress) across species (Ellman et al., 2008). Also, previous studies have primarily examined the relationship between maternal infection and psychiatric diagnoses and/or hospital admissions (Crow and Done, 1992; Machón et al., 1997; Murphy et al., 2017). This emphasis on severe cases of psychiatric disorders may limit the generalizability of findings to less severe cases and, consequently, it is important to examine the effect of maternal infection/inflammation on subthreshold symptoms during early developmental periods before psychiatric conditions tend to emerge (Crow and Done, 1992; Takei et al., 1993).

Internalizing and externalizing symptomology were both significantly associated with IL-6 in unadjusted analyses and differentially associated with higher levels of IL-1ra and IL-8, respectively, in adjusted and unadjusted analyses. The association of IL-1ra and IL-8 with internalizing and externalizing symptoms, respectively, is largely in accordance with previous findings. IL-1ra levels increase in response to psychosocial and physical (e.g., pathogens, injuries) events, activating multiple processes leading to fever, loss of appetite, somnolence, lethargy and decreased social activity in humans – sickness behaviors that overlap with internalizing symptoms (Dantzer, 2001). In animals, exposure to IL-1β during pregnancy is associated with higher expression of IL-1β in the human placenta, amniotic fluid, newborn blood and neonatal brain, white matter abnormalities as well as motor dysfunction (Arrode-Brusés and Brusés, 2012; Cai et al., 2000). IL-8 is a proinflammatory chemokine that helps mobilize and activate neutrophils, directing the migration of cells to the site of infection and/or injury (Janeway et al., 2005). IL-8 has been linked to structural brain abnormalities in animals (Willette et al., 2013) and humans (Ellman et al., 2010), increased risk of schizophrenia, and mediates the association between deficits in IQ/executive functioning in children born extremely preterm (Kuban et al., 2017). Given that externalizing symptoms in children are associated with cognitive dysfunction, it may be that fetal exposure to IL-8 increases risk for externalizing symptoms via cognitive impairment, but future research is necessary to resolve this question. Finally, higher T1 and T2 IL-6 were differentially associated with offspring externalizing and internalizing symptoms, respectively, in unadjusted analyses. IL-6 has been the cytokine most consistently associated with depression in non-pregnant studies, has been found to be a key mediator in brain and behavior changes in prenatal inflammation animal studies (Smith et al., 2007), and is one of the only cytokines that is known to cross the placenta (Zaretsky et al., 2004). After adjusting for covariates (race, maternal education, and sex), IL-6 associations became non-significant indicating that these demographic variables may be important contributors to IL-6 associations, which future studies should examine. Nevertheless, after adjusting for covariates (race, maternal education, and sex), IL-6 associations became non-significant indicating that future studies should examine potential interaction between IL-6 and the demographic variables.

Robust sex differences have been observed in the prevalence of multiple psychiatric disorders, including depression, autism, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia, substance use and eating disorders with both males and females differentially susceptible to different psychiatric disorders (Zahn-Waxler et al., 2008). The prevalence rates across multiple psychiatric conditions differs such that males are more likely to be diagnosed with am externalizing disorder, similar to the symptoms assessed in our study (e.g., conduct disorder) while females are more likely to be diagnosed with an adolescent-onset emotional disorder (e.g., depressive and anxiety disorders), however the cause of sex-based vulnerabilities to psychopathology remains unknown. Across many psychiatric disorders, the emergence of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in childhood are frequent prodromal features and, thus, results from this study suggest that differences in sex-based susceptibility to psychiatric disorders may be, at least in part, attributable to sex-based differences in the fetal susceptibility to MIP. Better characterizing the effect that MIP has on sex-based susceptibility to psychiatric disorder may play an important role in describing the etiology of psychiatric disorders more generally, as well as potentially identifying targets for early intervention and prevention strategies.

Confidence in results is strengthened by the use of a prospective, longitudinal design that creates a clear temporal precedence for exposure to inflammation. Second, serological assessment and the use of robust proxies of both TNF-α and IL1-β improve the precision of MIP measurement, and the conclusions on which these measures are based. Further, despite the use of archived serum, there was no evidence of serological degeneration, since detectable values were observed for all of the samples and did not differ from quality control samples (data available upon request). Further, it is unlikely that degradation of samples would occur preferentially for sera from specific mothers in the cohort in a systematic manner that would influence results. The present study did not conduct serological analyses of 3rd trimester sera, given increases in proinflammatory cytokines prior to the onset of labor and parturition that can reduce the ability to observe differences in inflammatory markers across individuals (Christiaens et al., 2008). Nevertheless, future studies should determine whether later periods of gestation influence differential offspring phenotypes. An important limitation, however, is that the analytic sample was reduced by the number of ‘Uncertain’ responses on maternal reports of both internalizing and externalizing symptoms, which may have decreased the level of maternal worry in the sample, given the associations between self-reported maternal worry and “uncertain” responses. A further limitation of the study is the reliance on questionnaire without accompanying normed data. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that the prevalence of internalizing and externalizing symptoms is systematically different in the CHDS sample compared to the general population. However, this risk is largely mitigated by the CHDS sample comprising a community sample consisting of virtually all pregnant women seeking obstetric care within a highly diverse county of the United States across a number of years. Additionally, our supplementary analyses indicated that there were no systematic differences in demographic, maternal health or inflammatory cytokine variables when comparing the analytic dataset to the overall sample. Moreover, the recruitment of virtually all pregnant mothers within a diverse county within the United States increases the likelihood that these findings generalize to the broader United States population.

These results from our study advance our understanding of how the intra uterine environment shapes risk for internalizing and externalizing symptoms in childhood. This study demonstrates that fetal sex and timing of MIP is important in understanding the role of MIP in offspring psychopathology, which could have implications for early identification and intervention strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH096478 awarded to Lauren Ellman and National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH101168 awarded to Lauren Alloy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: None

Conflict of Interest

The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Author Declaration

The authors confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. The authors further confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us.

The authors understand that the Corresponding Author is the sole contact for the Editorial process (including Editorial Manager and direct communications with the office). She is responsible for communicating with the other authors about progress, submissions of revisions and final approval of proofs. The authors confirm that we have provided a current, correct email address which is accessible by the Corresponding Author and which has been configured to accept email from ellman@temple.edu.

Reference

- Achenbach T, 1991. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile University of Vermont: Department of Psychiatry, Burlington, Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Allen NB, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, 1998. Prenatal and perinatal influences on risk for psychopathology in childhood and adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol 10(3), 513–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrode-Brusés G, Brusés JL, 2012. Maternal immune activation by poly (I: C) induces expression of cytokines IL-1β and IL-13, chemokine MCP-1 and colony stimulating factor VEGF in fetal mouse brain. J. Neuroinflammation 9(1), 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babri S, Doosti M-H, Salari A-A, 2014. Strain-dependent effects of prenatal maternal immune activation on anxiety-and depression-like behaviors in offspring. Brain. Behav. Immun 37, 164–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman MD, Iosif A-M, Smith SE, Bregere C, Amaral DG, Patterson PH, 2014. Activation of the maternal immune system during pregnancy alters behavioral development of rhesus monkey offspring. Biol. Psychiatry 75(4), 332–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, Zucker I, 2011. Sex bias in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 35(3), 565–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boksa P, 2010. Effects of prenatal infection on brain development and behavior: a review of findings from animal models. Brain. Behav. Immun 24(6), 881–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS, Derkits EJ, 2009. Prenatal infection and schizophrenia: a review of epidemiologic and translational studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 167(3), 261–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS, Hooton J, Schaefer CA, Zhang H, Petkova E, Babulas V, Perrin M, Gorman JM, Susser ES, 2004. Elevated maternal interleukin-8 levels and risk of schizophrenia in adult offspring. Am. J. Psychiatry 161(5), 889–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS, Sourander A, Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki S, McKeague IW, Sundvall J, Surcel H-M, 2014. Elevated maternal C-reactive protein and autism in a national birth cohort. Mol. Psychiatry 19(2), 259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Pan Z-L, Pang Y, Evans OB, Rhodes PG, 2000. Cytokine induction in fetal rat brains and brain injury in neonatal rats after maternal lipopolysaccharide administration. Pediatr. Res 47(1), 64-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canetta SE, Bao Y, Co MDT, Ennis FA, Cruz J, Terajima M, Shen L, Kellendonk C, Schaefer CA, Brown AS, 2014. Serological documentation of maternal influenza exposure and bipolar disorder in adult offspring. Am. J. Psychiatry 171(5), 557–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiaens I, Zaragoza DB, Guilbert L, Robertson SA, Mitchell BF, Olson DM, 2008. Inflammatory processes in preterm and term parturition. J. Reprod. Immunol 79(1), 50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL, 1991. A developmental perspective on intemalizing and externalizing disorders. In: Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology, in: Cicchetti D, Toth SL (Eds.), Internalizing and externalizing expressions of dysfunction Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Done D, 1992. Prenatal exposure to influenza does not cause schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 161(3), 390–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, 2001. Cytokine-induced sickness behavior: mechanisms and implications. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 933(1), 222–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depino A, 2015. Early prenatal exposure to LPS results in anxiety-and depression-related behaviors in adulthood. J Neurosci 299, 56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depino AM, 2018. Perinatal inflammation and adult psychopathology: From preclinical models to humans. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 77, 104–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Ruiz A, Tilz GP, Zangerle R, Baier-Bitterlich G, Wachter H, Fuchs D, 1995. Soluble receptors for tumour necrosis factor in clinical laboratory diagnosis. Eur. J. Haematol 54(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman LM, Deicken RF, Vinogradov S, Kremen WS, Poole JH, Kern DM, Tsai WY, Schaefer CA, Brown AS, 2010. Structural brain alterations in schizophrenia following fetal exposure to the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-8. Schizophr. Res 121(1), 46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman LM, Schetter CD, Hobel CJ, Chicz-DeMet A, Glynn LM, Sandman CA, 2008. Timing of Fetal Exposure to Stress Hormones: Effects on Newborn Physical and Neuromuscular Maturation. Dev. Psychobiol 50(3), 232–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg AM, Ellman LM, 2013. Inflammatory cytokines and neurological and neurocognitive alterations in the course of schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 73(10), 951–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg AM, Ellman LM, Schaefer CA, Maxwell SD, Shen L, Chaudhury NH, Cook AL, Bresnahan MA, Susser ES, Brown AS, 2016. Fetal exposure to maternal stress and risk for schizophrenia spectrum disorders among offspring: differential influences of fetal sex. Psychiatry Res 236, 91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabory A, Roseboom TJ, Moore T, Moore LG, Junien C, 2013. Placental contribution to the origins of sexual dimorphism in health and diseases: sex chromosomes and epigenetics. Biol. Sex Differ 4, 5–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman S, Cherkerzian S, Buka S, Hahn J, Hornig M, Goldstein J, 2016. Prenatal immune programming of the sex-dependent risk for major depression. Transl Psychiatry 6(5), e822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham AM, Rasmussen JM, Rudolph MD, Heim CM, Gilmore JH, Styner M, Potkin SG, Entringer S, Wadhwa PD, Fair DA, Buss C, 2018. Maternal Systemic Interleukin-6 During Pregnancy Is Associated With Newborn Amygdala Phenotypes and Subsequent Behavior at 2 Years of Age. Biol. Psychiatry 83(2), 109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin MR, Olmos L, Wang M, Valladares EM, Motivala SJ, Fong T, Newton T, Butch A, Olmstead R, Cole SW, 2007. Cocaine dependence and acute cocaine induce decreases of monocyte proinflammatory cytokine expression across the diurnal period: autonomic mechanisms. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 320(2), 507–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeway C, Travers P, Walport M, Schlomchik M, 2005. Immunobiology Garland Science Publishling. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M, 2002. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. J. Abnorm. Psychol 111(3), 411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuban KC, Joseph RM, O’shea TM, Heeren T, Fichorova RN, Douglass L, Jara H, Frazier JA, Hirtz D, Rollins JV, 2017. Circulating inflammatory-associated proteins in the first month of life and cognitive impairment at age 10 years in children born extremely preterm. J. Pediatr 180, 116–123. e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machón RA, Mednick SA, Huttunen MO, 1997. Adult major affective disorder after prenatal exposure to an influenza epidemic. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 54(4), 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon N, Kingsbury M, Mahedy L, Evans J, Colman I, 2017. The Association Between Prenatal Stress And Externalizing Symptoms In Childhood: Evidence From The Avon Longitudinal Study Of Parents And Children. Biol. Psychiatry [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maxwell SD, Fineberg AM, Drabick DA, Murphy SK, Ellman LM, 2018. Maternal prenatal stress and other developmental risk factors for adolescent depression: spotlight on sex differences. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol 46(2), 381–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan C, Harms L, Frost JD, Barreto R, Todd J, Schall U, Shannon Weickert C, Zavitsanou K, Michie PT, Hodgson DM, 2017. Effects of immune activation during early or late gestation on schizophrenia-related behaviour in adult rat offspring. Brain. Behav. Immun 63, 8–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer U, 2014. Prenatal poly (i: C) exposure and other developmental immune activation models in rodent systems. Biol. Psychiatry 75(4), 307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer U, Feldon J, Fatemi SH, 2009. In-vivo rodent models for the experimental investigation of prenatal immune activation effects in neurodevelopmental brain disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 33(7), 1061–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer U, Nyffeler M, Engler A, Urwyler A, Schedlowski M, Knuesel I, Yee BK, Feldon J, 2006. The time of prenatal immune challenge determines the specificity of inflammation-mediated brain and behavioral pathology. J. Neurosci 26(18), 4752–4762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mino Y, Oshima I, Okagami K, 2000. Seasonality of birth in patients with mood disorders in Japan. J. Affect. Disord 59(1), 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan V, Castle D, Page A, Fazio S, Gurrin L, Burton P, Montgomery P, Jablensky A, 1997. Influenza epidemics and incidence of schizophrenia, affective disorders and mental retardation in Western Australia: no evidence of a major effect. Schizophr. Res 26(1), 25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SK, Fineberg AM, Maxwell SD, Alloy LB, Zimmermann L, Krigbaum NY, Cohn BA, Drabick DA, Ellman LM, 2017. Maternal infection and stress during pregnancy and depressive symptoms in adolescent offspring. Psychiatry Res 257, 102–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana SA, Aavani T, Pittman QJ, 2012. Sex effects on neurodevelopmental outcomes of innate immune activation during prenatal and neonatal life. Horm. Behav 62(3), 228–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlotz W, Phillips DI, 2009. Fetal origins of mental health: evidence and mechanisms. Brain. Behav. Immun 23(7), 905–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Tu N, Patterson PH, 2005. Maternal influenza infection is likely to alter fetal brain development indirectly: the virus is not detected in the fetus. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci 23(2), 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simanek AM, Meier HC, 2015. Association between prenatal exposure to maternal infection and offspring mood disorders: a review of the literature. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 45(11), 325–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SE, Li J, Garbett K, Mirnics K, Patterson PH, 2007. Maternal immune activation alters fetal brain development through interleukin-6. J. Neurosci 27(40), 10695–10702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei N, O’callaghan E, Sham PC, Glover G, Murray R, 1993. Does prenatal influenza divert susceptible females from later affective psychosis to schizophrenia? Acta Psychiatr. Scand 88(5), 328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Meng X-H, Ning H, Zhao X-F, Wang Q, Liu P, Zhang H, Zhang C, Chen G-H, Xu D-X, 2010. Age-and gender-dependent impairments of neurobehaviors in mice whose mothers were exposed to lipopolysaccharide during pregnancy. Toxicol. Lett 192(2), 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willette A, Coe C, Birdsill A, Bendlin B, Colman R, Alexander A, Allison D, Weindruch R, Johnson S, 2013. Interleukin-8 and interleukin-10, brain volume and microstructure, and the influence of calorie restriction in old rhesus macaques. Age 35(6), 2215–2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, Marceau K, 2008. Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol 4, 275–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaretsky MV, Alexander JM, Byrd W, Bawdon RE, 2004. Transfer of inflammatory cytokines across the placenta. Obstet. Gynecol 103(3), 546–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Cazakoff BN, Thai CA, Howland JG, 2012. Prenatal exposure to a viral mimetic alters behavioural flexibility in male, but not female, rats. Neuropharmacology 62(3), 1299–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.