Abstract

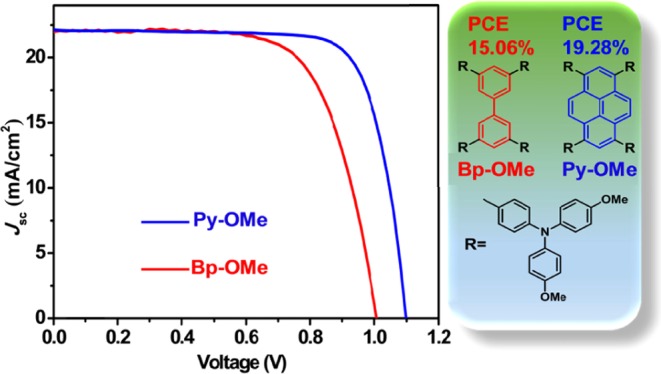

The simpler the design, the better and more effective it is. Two novel conjugated triarylamine derivatives in donor−π–donor structure employing biphenyl core and pyrene core as π-bridges, which are termed as Bp-OMe and Py-OMe, have been synthesized and characterized and then applied to perovskite solar cells (PSCs) as hole-transport materials (HTMs) successfully. Using 2,2′,7,7′-tetrakis(N,N-di-p-methoxy-phenylamine)-9,9′-spirobiuorene (spiro-OMeTAD) as a relative reference, Py-OMe-based PSCs showed the best power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 19.28% under AM 1.5 G illumination at 100 mW cm–2, which is comparable to that of PSCs based on spiro-OMeTAD with a best PCE of 18.57% with doping. Although Bp-OMe-based PSCs performed with relatively poor PCEs (best PCE of 15.06%) than those of Py-OMe-based PSCs, attributing to the poor planarity and hole mobility, taking the cost into consideration, Bp-OMe and Py-OMe are much more likely to be promising efficient HTMs for PSCs.

Introduction

When power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) in photovoltaic industry oriented by crystal silicon solar cells almost reached their peaks,1,2 the roaring across the horizon of organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite solar cells (PSCs) at the dawn of the 21th century gave the scientific and energy community a great surprise. Excellent photovoltaic properties, such as a large absorption scope, narrow band gap, high carrier mobility, long carrier diffusion, and high stability of the perovskite (PVSK) light-absorber in PSCs makes it the most striking material of the new generation in photovoltaics, and the skyrocketing PCEs, simplification of device architectures, and cost reduction of PSCs give infinite and positive possibilities.3,4

It has been certified by National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) recently that the PCEs of PSCs have reached to over 22% from the initial 3.8% by engineering of charge extracting layers and device architectures, as well as decrease in defects and hysteresis.5 It is good to be reminded that introducing hole-transport materials (HTMs) to PSC devices led to a noteworthy improvement in PCEs.6,7 Besides extracting holes from PVSK to metal electrodes, HTMs also prevent the backflow of electrons from PVSK to metal electrodes and determine the open voltage circuit (VOC) of PSCs.8 Owing to their excellent performance, organic small molecules 2,2′,7,7′-tetrakis(N,N-di-p-methoxy-phenylamine)-9,9′-spirobiuorene (spiro-OMeTAD) and macromolecule poly[-bis(4-phenyl)(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)amine] become the most successful and popularly employed HTMs in PSC devices.9,10 However, their disadvantages such as long synthetic route and high cost are negative to PSCs’ commercialization.11,12 Therefore, developing low-cost and efficient HTMs is still an urgent task. Recently, some organic small molecules that are typically linear,13 star-shaped,14,15 and butterfly-shaped16 donor−π–donor conjugated were introduced into PSCs as HTMs. Using molecules such as spiro[fluorene-9,9′-xanthene],17 thiophene,18 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene,19 carbazole,20 naphtho-dithiophene,21,22 and triazatruxene23 as π-bridges and diphenylamine, triphenylamine, or diarylamine-substituted carbazole as electron donors, these HTMs showed excellent photoelectric function performance in PSCs.

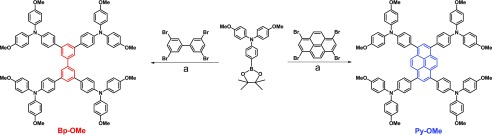

In this work, as shown in Scheme 1, two new triarylamine derivatives named as Bp-OMe and Py-OMe, respectively, employing biphenyl core and pyrene core as π-bridges were synthesized and characterized and then applied to PSCs as HTMs. For photoelectric conversion, using spiro-OMeTAD as an objective and relative reference, doping with lithium bis(trifluoromethane-sulfonyl)imide salt (Li-TFSI) and 4-tert-butylpyridine (TBP), Py-OMe-based PSCs showed the best PCE of 19.23% (under AM 1.5 G illumination at 100 mW cm–2), which is higher than that of PSCs based on spiro-OMeTAD with the best PCE of 18.57%. Although Bp-OMe-based PSCs performed with relatively poor PCEs (a best PCE of 15.06%) than those of Py-OMe-based PSCs, attributing to the poor planarity and hole mobility, taking the cost into consideration, Bp-OMe and Py-OMe are much more likely promising efficient HTMs for PSCs for they can be obtained by a one-step Suzuki–Miyaura C–C cross-coupling24 with high yields and sample purification. The estimated costs of Bp-OMe and Py-OMe are $62.7 and $50.1 g–1, respectively, much cheaper than that of our purchased spiro-OMeTAD (≈$176.5 g–1),12,25 making them very possible as prevailing commercial HTMs for PSCs. For PVSK absorber layer, replacing methylammonium (MA) with the larger formamidinium (FA) cation can further lower its band gap and extend light absorption to the infrared region.26−28 On the other hand, doping moderate bromide to the absolute iodine PVSK enhances the charge carrier lifetime. As has been reported, a combination of two PVSK materials with the nominal formula (FAPbI3)0.85(MAPbBr3)0.15 may create a higher PCE,28,29 so we used this kind of PVSK in the present paper.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Routes for Bp-OMe and Py-OMe by One Step.

a: Pd(PPh3)4, 2 M K2CO3, tetrahydrofuran (THF)/H2O (10:1), under N2, and reflux for 12 h.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

Biphenyl-triphenylamine and pyrene-triphenylamine derivatives (Bp-OMe and Py-OMe), which can be purified via simple recrystallization, were synthesized by one-step straightforward Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling under a N2 atmosphere in excellent overall yields (85% for Bp-OMe and 89% for Py-OMe), starting from commercial 4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)-N,N-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)aniline, brominated biphenyl, and brominated pyrene. The chemical structures of Bp-OMe and Py-OMe were confirmed by 1H/13C (400 MHz) NMR and high-resolution mass spectroscopy. The detailed synthesis, characterization, and cost estimation method of two new HTMs is shown in the Supporting Information.

Thermomechanical Analysis

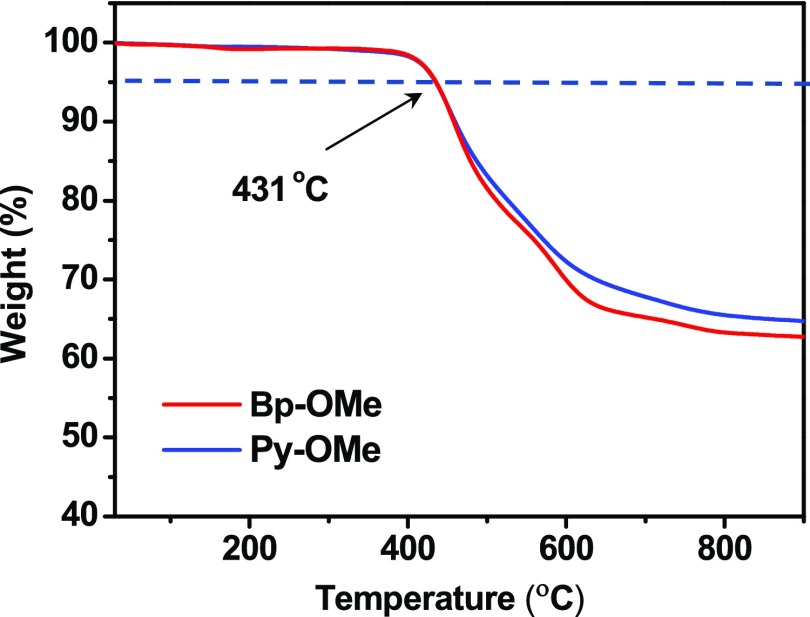

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) measurements were carried out to determine thermal properties of Bp-OMe and Py-OMe (Figure 1). It was found that Bp-OMe and Py-OMe show good thermal stability up to 431 °C, indicating that the change of π-linker does not influence thermal stability.

Figure 1.

Thermogravimetric analysis of Bp-OMe and Py-OMe at (scan rate: 10 °C min–1).

Energy Levels of HTMs Matching with Those of Perovskite

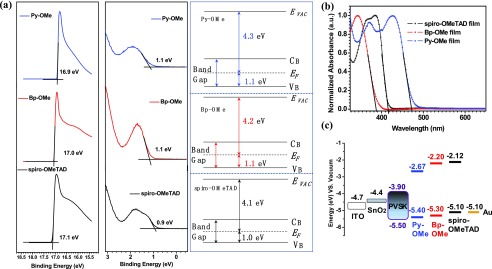

Ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) determined the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) energy levels of these organic molecule films.30,31 According to the UPS data in Figure 2a, HOMO energy levels of spiro-OMeTAD, Bp-OMe, and Py-OMe were calculated to be −5.10, −5.30, and −5.40 eV with respect to the vacuum level (Figure 2c), respectively. HOMO energy levels of Bp-OMe and Py-OM are located between the valence band of (FAPbI3)0.85(MAPbBr3)0.15 (−5.50 eV) and Au electrode (−5.10 eV), indicating that they are appropriate to extract the hole from PVSK absorber layer to Au electrodes. In addition, films of spiro-OMeTAD, Bp-OMe, and Py-OMe express their initial absorption band edges (λonset) at 416, 400, and 454 nm and maximum absorption wavelength (λmax) at 384, 342, and 426 nm, respectively (Figure 2c). Absorption regions of three HTMs appearing between 300 and 500 nm are assigned to the π–π* transitions resulting from their conjugated system.32−34 From the band gap formula Eg = 1240/λonset,35,36 the corresponding band gaps (Eg) for spiro-OMeTAD, Bp-OMe, and Py-OMe are 2.98, 3.10, and 2.73 eV, respectively. Lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy levels were calculated from the formula LUMO = HOMO – Eg(37) and values of LUMO energy levels of spiro-OMeTAD, Bp-OMe, and Py-OMe films were −2.12, −2.20, and −2.67 eV, respectively, meeting the requirements of preventing electron backflow from PVSK to metal electrodes. UPS and absorption results above are summarized in Table 1, and energy level diagram of indium tin oxide (ITO)/SnO2/(FAPbI3)0.85(MAPbBr3)0.15/HTM/Au devices is shown in Figure 2c. As the HOMO energy level of Py-OMe film is lower than that of Bp-OMe, we can expect a higher VOC of Py-OMe-based PSC.

Figure 2.

(a) UPS spectrum of spiro-OMeTAD, Bp-OMe, and Py-OMe films on Si substrates. (b) UV–vis absorption spectra of solid films of three HTMs. (c) Energy level distribution for each functional layer in PSC devices.

Table 1. UV–Vis Absorption and Energy Level Data of Spiro-OMeTAD, Bp-OMe, and Py-OMe films.

| compound | λmax (nm) | EHOMO (eV) | λonset (nm) | Eg (eV) | ELUMO (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| spiro-OMeTAD | 384 | –5.10 | 416 | 2.98 | –2.12 |

| Bp-OMe | 342 | –5.30 | 400 | 3.10 | –2.20 |

| Py-OMe | 426 | –5.40 | 454 | 2.73 | –2.67 |

Photovoltaic Conversion

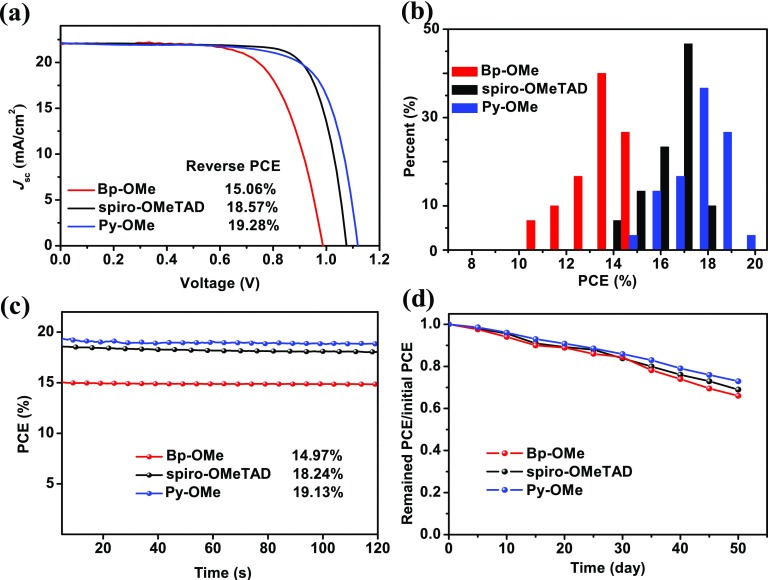

To evaluate the properties of two new HTMs, n–i–p type planar PSC devices based on spiro-OMeTAD, Bp-OMe, and Py-OMe doping with Li-TFSI and TBP were fabricated with a stack of ITO/SnO2/(FAPbI3)0.85(MAPbBr3)0.15/HTM/Au and here the device based on spiro-OMeTAD can be a good reference. Generally, in our devices, the thickness for SnO2, PVSK, HTM, and Au is 30, 600, 150, and 100 nm, respectively. For voltage scans from −1.2 to −0.2 V, current density–voltage (J–V) curves of three kinds of PSCs are shown in Figure 3a. Under the same conditions (AM 1.5 G, 100 mW cm–2), Py-OMe-based PSCs showed their best PCE at 19.28%, with a VOC of 1.11 V, short-circuit current (JSC) of 22.82 mA cm–2, and fill factor (FF) of 76.1% when devices based on spiro-OMeTAD performed at the best PCE of 18.57% and devices based on Bp-OMe performed at the best PCE at 15.06%, with a VOC of 0.98 V, short-circuit current (JSC) of 21.93 mA cm–2, and FF of 70.0%. The lower HOMO energy level of Py-OMe contributes to the higher VOC of PSCs based on Py-OMe, whereas JSC and FF are consistent with HTMs’ hole mobility and conductivity.38,39J–V curves of devices based on Bp-OMe, Py-OMe, and spiro-OMeTAD (Figure S1), which were scanned in two directions (100 mV s–1), were compared to study the hysteresis. There is only a hysteresis of 0.43 for the device’s PCE based on Py-OMe, whereas the hysteresis of the devices with Bp-OMe and spiro-OMe are 1.57 and 1.04, respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) J–V curves of PSCs based on three HTMs. (b) PCE distribution for devices under ambient conditions (30 devices were tested). (c) Stabilized PCEs of solar cells. (d) Devices’ PCE variations in 50 days without package under ambient conditions.

Thirty uniform PSC devices based on each HTM were measured to appraise Gaussian distributions and average values of corresponding photovoltaic parameters (Figure 3b and Table 2). The average PCE values are 13.29, 17.29, and 16.86% for PSCs based on Bp-OMe, Py-OMe, and spiro-OMeTAD, respectively. Furthermore, holding the voltage at the maximum power point, PCEs of 14.97, 19.13, and 18.24% corresponding to devices with Bp-OMe, Py-OMe, and spiro-OMeTAD all show good stability (Figure 3c). For long-term stability in a natural environment, the PCE of devices based on three HTMs can all maintain over 90% within 15 days and decrease to 65–70% in the 55th day and devices based on Py-OMe performed slightly more stable than Bp-OMe and spiro-OMeTAD-based PSCs (Figure 3d).

Table 2. Photovoltaic Parameters of the PSCs Based on Three HTMs and HTMs’ Hole Mobilities.

| compound | VOC (V) | JSC (mA cm–2) | FF (%) | PCE (%) | PCEavga (%) | hole mobilityb (cm2 V–1 s–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bp-OMe | 0.98 | 21.93 | 70.0 | 15.06 | 13.29 | 1.251 × 10–3 |

| spiro-OMeTAD | 1.10 | 22.50 | 75.0 | 18.57 | 16.86 | 4.375 × 10–3 |

| Py-OMe | 1.11 | 22.82 | 76.1 | 19.28 | 17.29 | 4.443 × 10–3 |

Hole Mobility Analysis

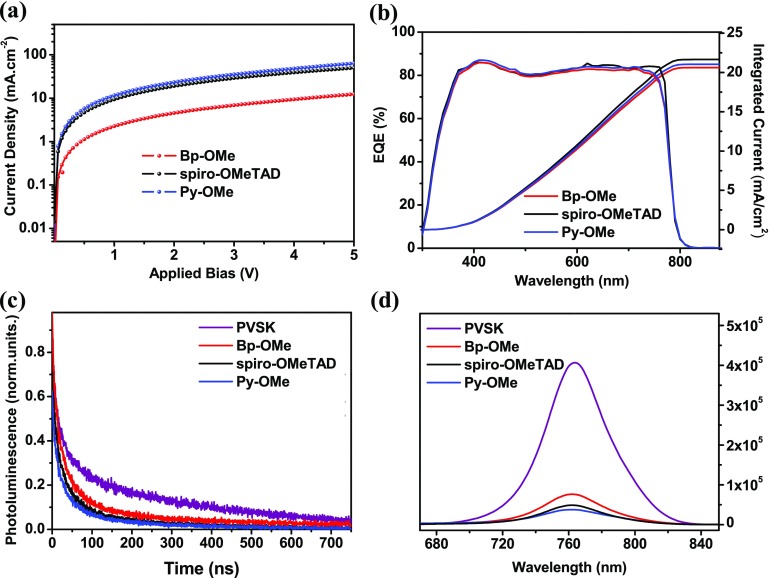

Prior to PSC fabrication, the hole-transport ability of HPB-OMe and HTB-OMe was measured by space-charge-limited current technique (Figure 4a) with the device structure ITO/poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS)/HTM/Au and calculated by the Mott–Gurney law,40 which is fitted by the J–V curves, investigated from the formula

where J is the current density, μ is the hole mobility, ε0 is the vacuum permittivity (8.85 × 10–12 F m–1), ε is the relative permittivity of the material (approaching 3 for organic semiconductors), V is the applied voltage, and d is the thickness of the active layer. For Bp-OMe, Py-OMe, and spiro-OMeTAD, the thicknesses are 180, 170, and 190 nm, respectively, which are measured by the step profiler. The hole mobility values of different HTMs are summarized in Table 2. Py-OMe film exhibits a hole mobility of 4.443 × 10–3 cm2 V–1 s–1, which is over 3.6 times that of Bp-OMe, which can be attributed to its intrinsic structure for the pyrene core that leads to a better layer-by-layer stacking.41

Figure 4.

(a) J–V curves for the hole-only ITO/PEDOT:PSS/HTM/Au devices. (b) Incident photon-to-current efficiency (IPCE) spectra for corresponding devices. (c) Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) spectra for the pristine PVSK film and PVSK/HTM bilayer, with excitation at 445 nm and monitoring at 765 nm. (d) Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of corresponding devices, with excitation at 600 nm.

Photoluminescence (PL) and Time-resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL)

Incident photon-to-current efficiency (IPCE) spectra of PSCs based on three HTMs are shown in Figure 4b. Spiro-OMeTAD-based devices reached a maximum of 91% external quantum efficiency (EQE), and Bp-OMe and Py-OMe-based devices exceeded 80% EQE from 380 to 760 nm spectral scope, which is slightly weaker than that of spiro-OMeTAD-based devices. The resultant IPCE values are in good agreement with JSC in the J–V curves and for spiro-OMeTAD, Bp-OMe, and Py-OMe are 22.63, 21.70, and 22.01 mA cm–2, respectively.

Time-resolved transient photoluminescence (TRPL) and continuous wave photoluminescence (PL) spectra were recorded to compare the carrier transfer and recombination in three kinds of PSCs.42,43 The radiative lifetimes of the pristine PVSK, PVSK/spiro-OMeTAD, PVSK/Bp-OMe, and PVSK/Py-OMe are about 60.3, 16.2, 28.5, and 18.7 ns, respectively. The shorter decay time of the Py-OMe-based device than that of Bp-OMe-based device demonstrates Py-OMe’s more effective hole extraction ability and less charge recombination in PSC devices. As shown in Figure 4d, the PL peak intensity of PVSK/Py-OMe is smaller than that of PVSK/Bp-OMe. It is consistent with the TRPL measurement that Py-OMe has stronger ability to extract, which can result in a better PCE.

Conclusions

In summary, we synthesized two novel conjugated triarylamine derivatives employing biphenyl core and pyrene core as π-bridges, which are termed as Bp-OMe and Py-OMe, and then applied to PSCs as HTMs. Best PCEs of 15.06, 18.57, and 19.28% under AM 1.5 G illumination at 100 mW cm–2 were measured for the devices with Bp-OMe, Py-OMe, and spiro-OMeTAD as HTMs with doping, respectively. Although Bp-OMe-based PSCs performed with relatively poor PCEs than those of Py-OMe-based PSCs, attributing to the poor planarity and hole mobility, taking the cost into consideration, Bp-OMe and Py-OMe are all likely to be promising efficient HTMs for PSCs.

Experimental Section

General Methods

Chemicals and reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification if not specially mentioned. Air-sensitive reactions were carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere. The device preparation was done in air atmosphere. NMR spectra were recorded in designated deuterated solvent on a Bruker Avance 400 MHz spectrometer at 298 K. Coupling constant (J) is given in Hz and chemical shift (δ) is given in parts per million (ppm). Mass data were obtained with a Bruker Daltonics Inc. Apex II FT-ICR or Autoflex III matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)-time-of-flight mass spectrometer. Emission spectra were recorded using an F-380 spectrofluorimeter of Tianjin Gangdong Sic. & Tech. Development Co. Ltd., with a red-sensitive photomultiplier tube R928F. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a TA Instruments TGAQ500 with a ramp of 10 °C min–1 under N2 from 100 to 900 °C.

Synthesis of Bp-OMe

A heterogeneous mixture of K2CO3 (0.54 g, 7.31 mmol), 4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)-N,N-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)aniline (1.08 g, 2.5 mmol), 3,3′,5,5′-tetrabromobiphenyl (235.0 mg, 0.5 mmol), and Pd(PPh3)4 (57.8 mg, 0.05 mmol) in THF/H2O (10:1, a total of 22 mL) was degassed for 20 min under nitrogen. After the reaction was heated at 90 °C for 18 h, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and then 10 mL of water was added. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 three times (3 × 20 mL), and the organic phase was combined. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the crude product was recrystallized in dichloromethane/methanol and washed with methanol to give the Bp-OMe as white solid (0.58 g, yield 85%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2SO) δ/ppm: 7.84 (s, 4H), 7.75 (s, 2H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 8H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 16H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 16H), 6.85 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 8H), 3.74 (s, 24H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2SO) δ/ppm: 155.8, 148.0, 141.6, 141.1, 140.0, 131.7, 127.7, 126.7, 123.1, 122.9, 119.5, 119.2, 114.9, 55.2. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) (MALDI): calcd for C92H78N4O8 [M + H]+, 1367.5783; found, 1367.5791.

Synthesis of Py-OMe

A heterogeneous mixture of K2CO3 (0.54 g, 7.31 mmol), 4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)-N,N-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)aniline (1.08 g, 2.5 mmol), 1,3,6,8-tetrabromopyrene (258.9 mg, 0.5 mmol), and Pd(PPh3)4 (57.8 mg, 0.05 mmol) in THF/H2O (10:1, a total of 22 mL) was degassed for 20 min under nitrogen. After the reaction was heated at 90 °C for 18 h, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and then 10 mL of water was added. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 three times (3 × 20 mL), and the organic phase was combined. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the crude product was recrystallized in dichloromethane/methanol and washed with methanol to give the Py-OMe as yellow solid (0.63 g, yield 89%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ/ppm: 8.16 (s, 4H), 7.89 (s, 2H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 8H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 16H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 8H), 6.80 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 16H), 3.72 (s, 24H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ/ppm: 155.4, 147.4, 140.1, 136.2, 132.1, 130.4, 129.1, 128.6, 127.0, 126.0, 124.2, 119.2, 113.9, 54.7. HRMS (MALDI): calcd for C96H78N4O8 [M + H]+, 1415.5821; found, 1415.5832.

Preparation of Perovskite Films and Device Fabrication

The conductive glass substrates (ITO-coated glass) were cleaned by ultrasonication in isopropanol (30 min), suds (30 min), deionized water (30 min), acetone (15 min), and isopropanol (30 min), respectively. Then, the cleaned ITO was dried under a flux of nitrogen and further cleaned in the UV-O3 cleaner for 30 min. The precursor solution of the electron transport layer (SnO2) was spin-coated onto ITO at 3000 rpm for 30 s, then annealed at 150 °C for 30 min. The perovskite precursor solution was prepared by dissolving 1.32 M PbI2, 0.12 M PbBr2, 1.08 M FAI, 0.24 M MAI, and 0.12 M MABr in dimethylformamide/dimethyl sulfoxide mixed solvent (v/v = 4:1). To fabricate the perovskite films, the precursor solution was spin-coated onto the SnO2-coated ITO at 4000 rpm for 25 s in air atmosphere and 2 mL of diethyl ether was dripped on the rotating substrate in 2 s before the surface changed to turbid. Then, the prepared perovskite film was annealed at 65 °C for 1 min and 100 °C for 2 min. Optimized concentrations in 1 mL of chlorobenzene were found to be 65 mM for spiro-OMeTAD and 20 mM for Bp-OMe and Py-OMe, respectively. Thirty microliters of 4-tert-butylpyridine (>96.0%, TCI), and 35 μL of lithium bis(trifluoromethane-sulfonyl)imide (Li-TFSI) (99.95%, Sigma-Aldrich) solution (260 mg Li-TFSI in 1 mL acetonitrile, 99.8%, Sigma-Aldrich) were added as additives. Then, the HTM solution was spin-coated onto the perovskite layer at 3000 rpm for 30 s. Due to the low solubility of Bp-OMe, the HTM solution as well as the substrate were heated to 100 °C for spin-coating. Finally, 100 nm of gold as the metal electrode on the HTM-coated films was evaporated in a metallization chamber.

The hole-only devices were fabricated by spin-coating PEDOT:PSS (1–3% in water) onto precleaned, patterned ITO substrates. A film of the HTM was spin-coated on top from its chlorobenzene solution with a concentration same as that for perovskite device fabrication. As a counter electrode, Au of 100 nm thickness was deposited on top by vacuum evaporation. The current density–voltage curves of the devices were recorded with a Keithley 2400 source.

Film and Device Characterization

The current density–voltage (J–V) curves were measured using a solar simulator manufactured by Enli Technology Co., Ltd. with a source meter (Keithley 2400) at 100 mA cm–2 illumination (AM 1.5 G). The light intensity was adjusted with an NREL-calibrated silicon solar cell. The active area (0.12 cm2) was defined with a mask with aperture. Transient-state photoluminescence (PL) was measured by FLS980 (Edinburgh Instruments Ltd.) with an excitation at 600 nm. All measurements of solar cells were conducted at room temperature under ambient atmosphere without encapsulation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation (21703008) and the Young Talent Thousand Program of China. The J–V measurement was performed via the solar simulator (SS-F5-3A, Enlitech) along with AM 1.5 G spectra whose intensity was calibrated by the certified standard silicon solar cell (SRC-2020, Enlitech) at 100 mV cm–2. The external quantum efficiency (EQE) data were obtained by using the solar-cell spectral-response measurement system (QE-R, Enlitech).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b01817.

J–V curves of devices under opposite scan directions and NMR and mass spectra of new compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Battaglia C.; Cuevas A.; De Wolf S. High-efficiency Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells: Status and Perspectives. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 1552–1576. 10.1039/C5EE03380B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock J.; Hettick M.; Geissbühler J.; Ong A. J.; Allen T.; Sutter-Fella C. M.; Chen T.; Ota H.; Schaler E. W.; De Wolf S.; et al. Efficient silicon solar cells with dopant-free asymmetric heterocontacts. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 15031. 10.1038/nenergy.2015.31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima A.; Teshima K.; Shirai Y.; Miyasaka T. Organometal halide perovskites as visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6050–6051. 10.1021/ja809598r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna A.; Sabba D.; Li H.; Yin J.; Boix P. P.; Soci C.; Mhaisalkar S. G.; Grimsdale A. C. Novel hole transporting materials based on triptycene core for high efficiency mesoscopic perovskite solar cells. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 2702–2709. 10.1039/C4SC00814F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakr Z. H.; Wali Q.; Fakharuddin A.; Schmidt-Mende L.; Brown T. M.; Jose R. Advances in hole transport materials engineering for stable and efficient perovskite solar cells. Nano Energy 2017, 34, 271–305. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.02.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gratia P.; Magomedov A.; Malinauskas T.; Daskeviciene M.; Abate A.; Ahmad S.; Grätzel M.; Getautis V.; Nazeeruddin M. K. Frontispiece: A Methoxydiphenylamine-Substituted Carbazole Twin Derivative: An Efficient Hole-Transporting Material for Perovskite Solar Cells. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 11409–11413. 10.1002/anie.201504666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy S. S.; Gunasekar K.; Heo J. H.; Im S. H.; Kim C. S.; Kim D.-H.; Moon J. H.; Lee J. Y.; Song M.; Jin S.-H. Solar Cells: Highly Efficient Organic Hole Transporting Materials for Perovskite and Organic Solar Cells with Long-Term Stability. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 686–693. 10.1002/adma.201503729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F.; Shan Y.; Qiao J.; Zhong C.; Wang R.; Song Q.; Zhu L. Replacement of Biphenyl by Bipyridine Enabling Powerful Hole Transport Materials for Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells with High Voc and FF. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 3833–3838. 10.1002/cssc.201700973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon N. J.; Noh J. H.; Yang W. S.; Kim Y. C.; Ryu S.; Seo J.; Seok S. I. Compositional engineering of perovskite materials for high-performance solar cells. Nature 2015, 517, 476–480. 10.1038/nature14133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon N. J.; Noh J. H.; Kim Y. C.; Yang W. S.; Ryu S.; Seok S. I. Solvent engineering for high-performance inorganic-organic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 897–903. 10.1038/nmat4014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawash Z.; Ono L. K.; Qi Y. Recent Advances in Spiro-MeOTAD Hole Transport Material and Its Applications in Organic–Inorganic Halide Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 5, 1700623 10.1002/admi.201700623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pham H. D.; Wu Z.; Ono L. K.; Manzhos S.; Feron K.; Motta N.; Qi Y.; Sonar P. Low-Cost Alternative High-Performance Hole-Transport Material for Perovskite Solar Cells and Its Comparative Study with Conventional SPIRO-OMeTAD. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2017, 3, 1700139 10.1002/aelm.201700139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazim S.; Ramos J. F.; Gao P.; Nazeeruddin M. K.; Grätzel M.; Ahmad S. A Dopant free Linear Acene derivative as a Hole Transport Material for Perovskite pigmented Solar Cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 1816–1823. 10.1039/C5EE00599J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K.; Kang M.-S.; Myung Y.; Seo J.-H.; Banerjee P.; Marks T. J.; Ko J. Star-shaped Hole Transport Materials with Indeno[1,2-b] thiophene or Fluorene on Triazine Core for Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 1186–1190. 10.1039/C5TA07369C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.; Zhao X.; Yi C.; Bi D.; Bi X.; Wei P.; Liu X.; Wang S.; Li X.; Zakeeruddin S. M.; Grätzel M. Dopant-free star-shaped hole-transport materials for efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Dyes Pigm. 2017, 136, 273–277. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2016.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.; Yi C.; Wei P.; Bi X.; Luo J.; Jacopin G.; Wang S.; Li X.; Xiao Y.; Zakeeruddin S. M.; Grätzel M. A Novel Dopant-Free Triphenylamine Based Molecular “Butterfly” Hole-Transport Material for Highly Efficient and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1600461 10.1002/aenm.201600401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B.; Zhang J.; Hua Y.; Liu P.; Wang L.; Ruan C.; Li Y.; Boschloo G.; Johansson E. M. J.; Kloo L.; et al. Tailor-Making Low-Cost Spiro[fluorene-9,9′-xanthene]-Based 3D Oligomers for Perovskite Solar Cells. Chem 2017, 2, 676–687. 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann I.; Urieta-Mora J.; Gratia P.; Aragó J.; Grancini G.; Molina-Ontoria A.; Ortí E.; Martín N.; Nazeeruddin M. K. High-Efficiency Perovskite Solar Cells Using Molecularly Engineered, Thiophene-Rich, Hole-Transporting Materials: Influence of Alkyl Chain Length on Power Conversion Efficiency. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1601674 10.1002/aenm.201601674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnaers B. J.; Schiepers E.; Weijtens C. H. L.; Meskers S. C. J.; Wienk M. M.; Janssen R. A. J. The effect of oxygen on the efficiency of planar p–i–n metal halide perovskite solar cells with a PEDOT:PSS hole transport layer. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 6882. 10.1039/C7TA11128B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskeviciene M.; Paek S.; Wang Z.; Malinauskas T.; Jokubauskaite G.; Rakstys K.; Cho K. T.; Magomedov A.; Jankauskas V.; Ahmad S.; et al. Carbazole-based Enamine: Low-cost and Efficient Hole Transporting Material for Perovskite Solar Cells. Nano Energy 2017, 32, 551–557. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irfan M.; Eliason B.; Mahr M. S.; Iqbal J. Tuning the Optoelectronic Properties of Naphtho-Dithiophene-Based A-D-A Type Small Donor Molecules for Bulk Hetero-Junction Organic Solar Cells. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 2352. 10.1002/slct.201702764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui B. B.; Yang N.; Shi C.; Yang S.; Shao J. Y.; Han Y.; Zhang L.; Zhang Q.; Zhong Y. W.; Chen Q. Naphtho[1,2-b:4,3-b′]dithiophene-Based Hole Transporting Materials for High-performance Perovskite Solar Cells: Molecular Engineering and Opto-electronic Properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 10057. 10.1039/C8TA02071J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rakstys K.; Abate A.; Dar M. I.; Gao P.; Jankauskas V.; Jacopin G.; Kamarauskas E.; Kazim S.; Ahmad S.; Grätzel M.; Nazeeruddin M. K. Triazatruxene-Based Hole Transporting Materials for Highly Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 16172. 10.1021/jacs.5b11076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torborg C.; Beller M. ChemInform Abstract: Recent Applications of Palladium-Catalyzed Coupling Reactions in the Pharmaceutical, Agrochemical, and Fine Chemical Industries. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 3027–3043. 10.1002/adsc.200900587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teh C. H.; Daik R.; Lim E. L.; Chi C. Y.; Ibrahim M. A.; Ludin N. A.; Sopian K.; Teridi M. A. M. A review of organic small molecule-based hole-transporting materials for meso-structured organic–inorganic perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 15788–15822. 10.1039/C6TA06987H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eperon G. E.; Stranks S. D.; Menelaou C.; Johnston M. B.; Herz L. M.; Snaith H. J. Formamidinium of Formamidinium lead trihalide: a broadly tunable perovskite for efficient planar heterojunction solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 982. 10.1039/c3ee43822h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Liu N.; Xu Z.; Chen Q.; Wang X.; Zhou H. Precise Composition Tailoring of Mixed-Cation Hybrid Perovskites for Efficient Solar Cells by Mixture Design Methods. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 8804. 10.1021/acsnano.7b02867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J. W.; Liu L.; Zhang D.; Marco N. D.; Lee J. W.; Lin O.; Chen Q.; Yang Y. The Emergence of the Mixed Perovskites and Their Applications as Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700491 10.1002/aenm.201700491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Li L.; Liu Z.; Jiao H.; He Y.; Wang X.; Zhu R.; Wang D.; Sun J.; Chen Q.; Zhou H. The intrinsic properties of FA(1–x)MAxPbI3 perovskite single crystals. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 8537. 10.1039/C7TA01441D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong D. A.; Lee S.; Chung J.; Park Y.; Suh M. C. Impact of Interface Mixing on the Performance of Solution Processed Organic Light Emitting Diodes—Impedance and Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy Study. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 22748. 10.1021/acsami.7b03557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shallcross R. C.; Zheng Y.; Saavedra S. S.; Armstrong N. R. Determining Band-Edge Energies and Morphology-Dependent Stability of Formamidinium Lead Perovskite Films Using Spectroelectrochemistry and Photoelectron Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 4866. 10.1021/jacs.7b00516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura H.; Ishida N.; Shimazaki A.; Wakamiya A.; Saeki A.; Scott L. T.; Murata Y. Hole-Transporting Materials with a Two-Dimensionally Expanded π-System around an Azulene Core for Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 15656–15659. 10.1021/jacs.5b11008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. C.; Lee Y. H.; Chen C. Y.; Kau K. C.; Lin L. Y.; Dai C. A.; Wu C. G.; Ho K. C.; Wang J. K.; Wang L. Self-Assembled All-Conjugated Block Copolymer as an Effective Hole Conductor for Solid-State Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 1254–1262. 10.1021/nn404346v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo J. H.; Park S.; Im S. H.; Son H. J. Development of Dopant-Free Donor-Acceptor-type Hole Transporting Material for Highly Efficient and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 39511. 10.1021/acsami.7b11938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Zhu Z.; Chueh C.-C.; Jo S. B.; Luo J.; Jang S.-H.; Jen A. K.-Y. Rational Design of Dipolar Chromophore as an Efficient Dopant-free Hole-Transporting Material for Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11833. 10.1021/jacs.6b06291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.; Byranvand M. M.; Kang G.; Son S. Y.; Song S.; Kim G. W.; Park T. Green-Solvent-Processable, Dopant-Free Hole-Transporting Materials for Robust and Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12175. 10.1021/jacs.7b04949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Li Y.; Chen C.; Wang L.; Zhang J. Design new hole transport materials for efficient perovskite solar cells by suitable combination of donor and core groups. Org. Electron. 2017, 49, 255–261. 10.1016/j.orgel.2017.06.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna A.; Grimsdale A. C. Hole Transporting Materials for Mesoscopic Perovskite Solar Cells-Towards a Rational Design. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 16446–16466. 10.1039/C7TA01258F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwala P.; Kabra D. A review on triphenylamine (TPA) based organic hole transport materials (HTMs) for dye sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) and perovskite solar cells (PSCs): evolution and molecular engineering. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 1348–1373. 10.1039/c6ta08449d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Hu J.; Jiao H.; Li L.; Zheng G.; Chen Y.; Huang Y.; Zhang Q.; Shen C.; Chen Q.; Zhou H. Chemical Reduction of Intrinsic Defects in Thicker Heterojunction Planar Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1606774 10.1002/adma.201606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timalsina A.; Hartnett P. E.; Melkonyan F.; Strzalka J.; Reddy V. S.; Facchetti A.; Wasielewski M. R.; Marks T. New Donor Polymer with Tetrafluorinated Blocks for Enhanced Performance in Perylenediimide-Based Solar Cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 5351–5361. 10.1039/C7TA00063D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D.; Bartesaghi D.; Wei H.; Hutter E. M.; Huang J.; Savenije T. J. Photoluminescence from Radiative Surface States and Excitons in Methylammonium Lead Bromide Perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 4258. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b01642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson K. T.; Grieco C.; Kennehan E. R.; Stewart R. J.; Asbury J. B. Time-Resolved Infrared Spectroscopy Directly Probes Free and Trapped Carriers in Organo-Halide Perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 651–658. 10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.