Abstract

In this work, we disclose an advanced general process for the synthesis of tailor-made α-amino acids (α-AAs) via tandem alkylation–second-order asymmetric transformation. The first step is the alkylation of the chiral Ni(II) complex of glycine Schiff base, which is conducted under mild phase-transfer conditions allowing the structural construction of target α-AAs. The second step is based on the methodologically rare second-order asymmetric transformation, resulting in nearly complete precipitation of the corresponding (SC,RN,RC)-configured diastereomer, which can be collected by a simple filtration. The operational convenience and potential scalability of all experimental procedures, coupled with excellent stereochemical outcome, render this method of high synthetic value for the preparation of various tailor-made α-AAs.

Introduction

Amino acids (AAs) are among a handful of paramount molecules involved in virtually all aspects of the phenomenon of life. Quite naturally, they played a significant role in organic, bioorganic, medicinal, and pharmaceutical chemistry from the earliest days of modern healthcare and life sciences.1 In particular, the use of tailor-made2 AAs in the design of peptides/peptidomimetics with restricted number of conformations and precise positioning of the side-chains in the χ-space3 is a well-established paradigm in the modern pharmaceutical industry.1,4,5 Quite interestingly, one of the emerging areas of tailor-made AA application is the biological containment strategy of the produced genetically modified organisms.6 Accordingly, the current interest in the asymmetric synthesis of tailor-made AAs7 and their analogues, such as amino sulfonic,8 phosphonic,9 and fluorine-containing10 acids, is at an all-time high, targeting novel structural motifs, functions, and properties. Consistent with our continuous interest in asymmetric synthesis of various tailor-made AAs, for example, fluorine-11 and phosphorus-containing,12 sterically constrained,13 and their nonlinear chiroptical properties, such as self-disproportionation of enantiomers,14 we were actively developing the Ni(II) complex chemistry of AA Schiff bases4d,7d,7e as a general approach for the preparation of tailor-made AAs (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. General Approach for the Asymmetric Synthesis of AAs via Ni(II) Complexes of Schiff Bases.

As shown in Scheme 1, trichloro-substituted ligand (S)- or (R)-1, currently the most frequently used source of recyclable chirality in this method,15 is reacted with glycine and a source of Ni(II) ions to produce the Schiff base complex 2.16 The square-planar Ni(II) complex 2 serves as a versatile chiral nucleophilic glycine equivalent to afford products 3 by the reactions with various electrophilic reagents. Most commonly used reaction types include, for example, alkyl halide alkylations,17 Michael,18 aldol,19 and Mannich20 addition reactions. Intermediate products 3 can be conveniently disassembled to release target AAs 4–10 and to recycle chiral tridentate ligand 1. This method can be used for the preparation of general type α-AAs 4, β-functionalized/substituted derivatives 5, sym-6,21 or chiral quaternary 7(22) α-AAs, in particular, (1R,2S)-1-amino-2-vinylcyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid 8(23) and bis-α-AAs of type 9.24 Moreover, the major advantage of this method over other well-developed general approaches7b,7c,25 is its exceptionally successful application for kinetic resolution of unprotected α- and β-AAs of types 4(26) and 10,27 respectively. This latter application was shown to be competitive with traditionally economically attractive enzymatic approaches.28 Most recently, using the modular approach29 for the design of chiral tridentate ligands, we developed a series of ligands featuring free N–H functionality and multiple stereogenic centers.30 In particular, the adamantyl-containing derivative 11 (Scheme 2) was found to possess some remarkable physicochemical properties for the development of second-order asymmetric transformation (SOAT) approach for the general synthesis of α-AAs.31

Scheme 2. Applications of (S)-Rimantadine-Derived Ligand 11; Previous Work on SOAT of Racemic α-AAs and This Work Dealing with Tandem Alkylation–SOAT, for General Asymmetric Synthesis of α-AAs.

As presented in Scheme 2, in the previous work, we demonstrated that the newly designed ligand 11 readily reacts with racemic α-AAs 12 to produce a mixture of four theoretically possible diastereomeric products.31 However, because of the extreme lipophilicity of the adamantyl moiety,32 one of the diastereomers, (SC,RN,RC)-configured 13, precipitates from the methanol or aqueous methanol solution, thus driving the equilibrium of all other diastereomers to the one major reaction product. As the next logical step in the advancement of this methodology, we now report a tandem alkylation–SOAT protocol, which includes synthesis of glycine Schiff base Ni(II) complex 14 and its alkylation under phase-transfer catalysis (PTC) conditions followed by SOAT via equilibration/precipitation of major products 15.

Results and Discussion

Unlike the asymmetric synthesis, where the major product is a result of preferential stereochemical interactions, which can be comprehended, predicted, and rationally designed, the SOAT is essentially a serendipitous approach resulting from rather complex and multifactorial interplay of numerous chemical/steric/physical properties.33 Nevertheless, success in developing a SOAT process using ligand 11 was predicated on the idea of “extreme” lipophilic properties32 of the corresponding rimantadine-containing Ni(II) complexes.31 Drawing from the previous results, we decided to extend the synthetic versatility of this approach by preparing the required diastereomeric complexes not via the reactions of ligand 11 with racemates of the target α-AAs but via homologation of the intermediate glycine derivative. To this end, we focused on the synthesis of required glycine complexes 14 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Optimized Conditions for the Preparation of the Requisite Ni(II) Complexes of Glycine (SC,RN)-14 and (SC,SN)-14.

After some extensive experimentation, we found that the application of Na2CO3 as a base, in combination with catalytic amounts of n-Bu4NI, provides for the most practical preparation of the target glycine complexes (SC,RN)-14 and (SC,SN)-14, in about 3:1 ratio. Under these conditions, using only 10% excess of glycine and the Ni(II) source allowed for the complete conversion of the starting ligand (S)-11 to products 14, isolated with quantitative chemical yield. Clean preparation of glycine complexes 14 was very important part of the project allowing us to avoid any unnecessary purification of the intermediate derivatives. Having achieved virtually byproduct-less synthesis of glycine complexes 14, we focused on the next alkylation step. On the basis of the previous research,4d we selected PTC conditions34 allowing for very mild homologation of the glycine moiety with usually excellent chemical yields. The results obtained are summarized in Scheme 4.

Scheme 4. Alkylation of Ni(II) Complexes of Glycine (SC,RN)-14 and (SC,SN)-14 under PTC Conditions; Equilibration of Diastereomeric Complexes 17–19 and 15 and Precipitation of the Final Major Product (SC,RN,RC)-15.

As a model experiment, we selected the alkylation reaction using m-bromobenzyl bromide 16 (Scheme 4). In this case, the expected product 15a was previously obtained using the reaction of racemic AA with ligand (S)-11,31 thus facilitating the identification and stereochemical assignments. Starting glycine complexes 14 were used as obtained, without any purification, as a 3:1 mixture of (SC,RN)-14 and (SC,SN)-14 diastereomers. We found that using 1,2-dichloroethane as an organic solvent, 30% aqueous NaOH as a base, and 25 mol % of n-Bu4NI as a phase-transfer catalyst, virtually complete consumption of starting glycine complexes 14 can be achieved in about 10 min of the reaction time. Analysis of the reaction mixture by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) showed expected alkylation products 15a as a major (>50%) product and 17a–19a as minor products. The stereogenic nitrogen and AA α-carbon atoms in compounds 15a and 17a–19a are configurationally unstable. Therefore, under the basic conditions, all four diastereomers undergo rapid epimerization and interconversion via stepwise inversion of either nitrogen or α-carbon or both atoms. Nonetheless, diastereomeric products 15a and 17a–19a are compounds of different chemical properties, in particular, the solubility in a given solvent, providing the opportunity for a SOAT process. Indeed, the major diastereomer (SC,RN,RC)-15a was found to gradually precipitate from the reaction mixture, leading to a progressive transformation of more soluble 17a–19a to the crystalline precipitate of compound 15a. Thus, after about 1 h of stirring at room temperature, the reaction mixture was filtered affording diastereomerically pure (SC,RN,RC)-15a with 92.4% yield.

This tandem alkylation–SOAT protocol was found to be of general application for the preparation of various phenylalanine-type tailor-made α-AAs. For example, the derivatives of p-bromo- (15b), p-chloro- (15c), p-trifluoromethyl- (15d), p-iodo- (15e), and p-nitro-substituted (15f) phenylalanines were readily prepared in diastereomerically pure form under the same conditions using filtration as the final isolation procedure. Of particular interest is the preparation of naphthylalanine derivative (SC,RN,RC)-15g, which was isolated with respectable chemical yield. In the case of compounds 15c,e, and f, the application of the standard conditions gave relatively lower isolated yields of ∼50–56%. In this regard, we would like to emphasize that relatively modest isolated yields are the result of incomplete precipitation of the major diastereomer from the reaction mixture. Furthermore, it should be noted that under the SOAT conditions, the isolated yield depends on a physicochemical property which can be conditioned by optimizing the solvent system for each particular case.33 For instance, a gradual addition of water to the reaction mixture leads to a lower solubility of products allowing increasing precipitation of the target products. This possibility was demonstrated on the example of product 15f, yield of which was improved from 56.5 to 86.5% by adding about 20% of water to the reaction mixture (see Supporting Information). It should be noted, however, that the diastereomeric purity of thus prepared complex 15f was 93.2% de. On the other hand, attempts to use this tandem procedure for the preparation of α-AA-containing alkyl side-chains were unsuccessful. The major problem we encountered was low reactivity of alkyl halides under the PTC conditions.

Diastereomerically pure Ni(II) complexes 15 can be readily disassembled to release the target AAs or their protected derivatives.4d For example, diastereomer (SC,RN,RC)-15a was treated with 3 N HCl in methanol to produce m-bromo-phenylalanine (R)-20 and chiral ligand (S)-11 (Scheme 5). The latter, configurationally uncompromised, was almost quantitatively recovered and reused for continuous synthesis of other AAs.

Scheme 5. Disassembly of Diastereomerically Pure (SC,RN,RC)-15a; Isolation of Target Fmoc-Derivative of AA (R)-21 and Recycling of Chiral Ligand (S)-11.

AA (R)-20 was not isolated in analytically pure form but transformed in situ to the corresponding Fmoc derivative (R)-21. The standard protection protocol with application of N-(9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyloxy)succinimide (Fmoc-OSu) was used, with an exception that ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was added to chelate the Ni(II) ions.

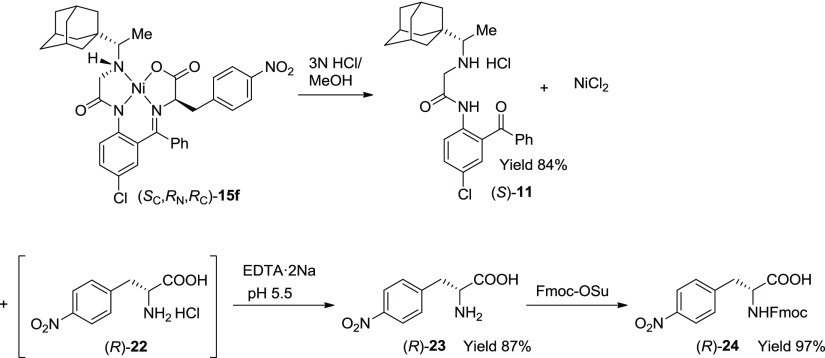

In another example, presented in Scheme 6, we demonstrate the isolation of free p-nitro-phenylalanine (R)-23. Thus, after the disassembly of diastereomerically pure Ni(II) complex (SC,RN,RC)-15f in methanol under the action of 3 N HCl, AA (R)-23 was isolated by precipitation at the isoelectric point (pH 5.5) in the presence of EDTA to chelate the Ni(II) ions. For the further use of this tailor-made AA in our peptide-related projects, we also prepared Fmoc-protected derivative (R)-24, similar to the preparation of m-bromo-phenylalanine (R)-21 (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6. Disassembly of Diastereomerically Pure (SC,RN,RC)-15f; Isolation of Target-Free AA (R)-23 and Its Fmoc Derivative (R)-24, as Well as the Recycling of Chiral Ligand (S)-11.

Conclusions

We demonstrate that Ni(II) complexes (SC,RN)- and (SC,SN)-14, derived from glycine Schiff base and (S)-rimantadine, can be regioselectivity alkylated on the glycine residue under the PTC conditions affording a mixture of up to four diastereomeric products. Without purification, the alkylated products can be submitted to the SOAT conditions allowing a transformation of the diastereomeric mixture to single precipitated stereoisomer 15 of (SC,RN,RC) absolute configuration. The operational convenience and chromatography-free experimental procedures render this method of potentially high synthetic value for the preparation of phenylalanine-type tailor-made α-AAs.

Experimental Section

General Information

All reagents and solvents were used as received. The reaction mixture was magnetically stirred and monitored with the aid of TLC on precoated silica gel plates, and visualization was carried out using UV light and ninhydrin. Flash chromatography was performed with the indicated solvents on silica gel (particle size 0.040–0.063 mm). Yields reported are for isolated, spectroscopically pure compounds. 1H and 13C spectra were recorded on a 300 MHz Brüker instrument. Chemical shifts are given in ppm (δ), referenced to the residual proton resonances of the solvents. Coupling constants (J) are given in Hz. The letters s, d, t, q, m, and br stand for singlet, doublet, triplet, quartet, multiplet, and broad, respectively. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded using an ultraperformance liquid chromatography/quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry system in the ESI mode.

Procedure for the Preparation of Ni(II) Complexes by Reaction of Ligand (S)-11 with Glycine

To a mixture of ligand (S)-11 (1.0 g, 2.22 mmol), nickel(II) nitrate hexahydrate (0.71 g, 2.44 mmol), glycine (0.18 g, 2.44 mmol), tetrabutylammonium iodide (0.08 g, 10 mol %), and methanol (40 mL) was added sodium carbonate (1.18 g, 11.1 mmol), and the reaction mixture was stirred at reflux for 2 h. After the ligand (S)-11 was consumed, the reaction was quenched by pouring icy 5% aqueous acetic acid (200 mL) to give a precipitate. The precipitate was filtrated, washed with 5% aqueous acetic acid, and dried in vacuo at 50 °C overnight to afford the diastereomixture of Ni(II) complex (SC,RN)-14 and (SC,SN)-14. A 3:1 ratio mixture of two diastereomers was obtained. The spectral data were reported in our previous literature.

General Procedure for the Preparation of Ni(II) Complexes via Tandem Alkylation of Ni(II) Complexes of Glycine (SC,RN)-14 and (SC,SN)-14

To a solution of Ni(II) complexes of glycine (SC,RN)-14 and (SC,SN)-14 (1 equiv) in 1,2-dichloroethane (8 volumes), 30% aqueous sodium hydroxide solution (40 equiv) was added followed by tetrabutylammonium iodide (25 mol %) and the corresponding alkyl halide (1.1 equiv). After stirring at room temperature (rt) for 10–30 min, the reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted with dichloromethane; then, the organic layer was evaporated to dryness. The obtained residue and potassium carbonate (4 equiv) were stirred in methanol (40 volumes) at reflux for 1 h. After the reaction, several amounts of water were dropped to the mixture to give a precipitate. The precipitate was filtrated, washed with aqueous methanol, and dried in vacuo at 60 °C overnight to afford the corresponding Ni(II) complex.

Ni(II)/(S)-11/(R)-2-Amino-3-(3-bromophenyl)propanoic Acid Schiff Base Complex (SC,RN,RC)-15a

Yield: 92.4%. The spectral data were reported in our previous literature.

Ni(II)/(S)-11/(R)-2-Amino-3-(4-bromophenyl)propanoic Acid Schiff Base Complex (SC,RN,RC)-15b

Yield: 79.3%. [α]D25 −2511 (c 0.050, CHCl3). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.38 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.34–1.46 (m, 6H), 1.58–1.80 (m, 6H), 2.04 (s, 3H), 2.39 (br, 1H), 2.48 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 2.73 (dd, J = 5.1, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 3.07 (dd, J = 2.5, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 3.12–3.20 (m, 2H), 4.34 (dd, J = 3.0, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.08–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.26–7.34 (m, 2H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.57–7.67 (m, 3H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 8.49 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 10.2, 28.5, 36.8, 36.9, 39.1, 39.8, 50.9, 63.0, 72.9, 122.1, 125.7, 126.2, 127.7, 127.7, 128.7, 129.8, 130.0, 130.9, 132.0, 132.7, 132.9, 133.3, 133.9, 136.0, 142.2, 169.8, 177.8, 179.6. HRMS: calcd for C36H38BrClN3NiO3 [M + H]+, 732.1139; found, 732.1152.

Ni(II)/(S)-11/(R)-2-Amino-3-(4-chlorophenyl)propanoic Acid Schiff Base Complex (SC,RN,RC)-15c

Yield: 50.8%. [α]D25 −2886 (c 0.045, CHCl3). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.28 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.23–1.35 (m, 6H), 1.46–1.69 (m, 6H), 1.93 (s, 3H), 2.26–2.34 (m, 1H), 2.39 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 2.64 (dd, J = 5.1, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 2.94–3.07 (m, 3H), 4.23 (dd, J = 3.2, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 6.66 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.98–7.03 (m, 1H), 7.16–7.23 (m, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.48–7.55 (m, 5H), 8.38 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.8, 28.0, 36.3, 36.5, 38.7, 39.3, 50.4, 62.7, 72.4, 125.2, 125.8, 127.2, 127.3, 128.2, 128.6, 129.4, 129.6, 130.4, 132.3, 132.5, 132.9, 133.1, 133.6, 135.0, 141.7, 169.4, 177.5, 179.1. HRMS: calcd for C36H38Cl2N3NiO3 [M + H]+, 688.1644; found, 688.1639.

Ni(II)/(S)-11/(R)-2-Amino-3-(4-trifluorophenyl)propanoic Acid Schiff Base Complex (SC,RN,RC)-15d

Yield: 73.4%. [α]D25 −2019 (c 0.054, CHCl3). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.27 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.16–1.33 (m, 6H), 1.42–1.68 (m, 6H), 1.91 (s, 3H), 2.25 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 2.44 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 2.75 (dd, J = 5.1, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 2.85–3.11 (m, 3H), 4.21–4.31 (m, 1H), 6.67 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.96–7.05 (m, 1H), 7.14–7.27 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.58 (m, 5H), 7.78 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 8.42 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.6, 28.0, 36.3, 36.4, 38.6, 39.8, 50.4, 63.0, 72.1, 124.2 (q, J = 272.4 Hz), 125.1, 125.3 (q, J = 3.7 Hz), 125.8, 127.3, 127.4, 128.2, 129.4, 129.6, 130.1 (q, J = 32.3 Hz), 130.5, 131.9, 132.4, 132.7, 132.9, 140.7 (q, J = 1.4 Hz), 141.8, 169.8, 177.5, 179.0. HRMS: calcd for C37H38ClF3N3NiO3 [M + H]+, 722.1907; found, 722.1897.

Ni(II)/(S)-11/(R)-2-Amino-3-(4-iodephenyl)propanoic Acid Schiff Base Complex (SC,RN,RC)-15e

Yield: 53.5%. [α]D25 −2558 (c 0.050, CHCl3). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.28 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 1.25–1.36 (m, 6H), 1.48–1.69 (m, 6H), 1.94 (s, 3H), 2.21–2.30 (m, 1H), 2.35 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 2.60 (dd, J = 4.9, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 2.94 (dd, J = 3.3, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 3.00–3.15 (m, 2H), 4.23 (dd, J = 3.3, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.96–7.05 (m, 1H), 7.15–7.26 (m, 4H), 7.46–7.55 (m, 3H), 7.88 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 8.39 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.8, 28.0, 36.3, 36.4, 38.6, 39.4, 50.6, 62.5, 72.5, 93.0, 125.2, 125.7, 127.2, 127.2, 128.2, 129.3, 129.5, 130.4, 132.2, 132.4, 132.8, 133.8, 136.2, 137.5, 141.7, 169.3, 177.3, 179.2. HRMS: calcd for C36H38ClIN3NiO3 [M + H]+, 780.1000; found, 780.0981.

Ni(II)/(S)-11/(R)-2-Amino-3-(4-nitrophenyl)propanoic Acid Schiff Base Complex (SC,RN,RC)-15f

Yield: 56.5%. [α]D25 −2237 (c 0.058, CHCl3). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.31 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.20–1.39 (m, 6H), 1.42–1.69 (m, 6H), 1.92 (s, 3H), 2.49–2.66 (m, 2H), 2.88–3.15 (m, 4H), 4.16–4.28 (m, 1H), 6.68 (s, 1H), 6.99 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.46–7.62 (m, 3H), 8.23 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 8.45 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 10.0, 28.4, 36.8, 39.2, 40.5, 51.0, 63.8, 71.9, 123.8, 125.4, 126.3, 127.7, 127.8, 128.3, 129.9, 130.1, 131.0, 132.1, 132.8, 133.3, 142.2, 144.2, 148.1, 170.6, 177.8, 179.2. HRMS: calcd for C36H38ClN4NiO5 [M + H]+, 699.1884; found, 699.1882.

Ni(II)/(S)-11/(R)-2-Amino-3-(naphthalen-2-yl)propanoic Acid Schiff Base Complex (SC,RN,RC)-15g

Yield: 88.1%. [α]D25 −2412 (c 0.046, CHCl3). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.96 (s, 6H), 1.10 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.34–1.63 (m, 8H), 1.82 (s, 3H), 2.16 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 2.45 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 2.80 (dd, J = 5.3, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 3.20 (dd, J = 3.0, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (dd, J = 2.9, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.10–7.26 (m, 4H), 7.43–7.61 (m, 5H), 7.86–8.10 (m, 4H), 8.33 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.9, 28.3, 36.3, 36.8, 38.7, 40.2, 49.9, 62.6, 73.3, 125.6, 126.0, 127.1, 127.2, 127.7, 127.8, 128.0, 128.6, 129.7, 129.9, 130.6, 130.7, 130.8, 132.6, 132.7, 133.2, 133.3, 133.9, 134.5, 142.2, 169.4, 178.2, 179.6. HRMS: calcd for C40H41ClN3NiO3 [M + H]+, 704.2190; found, 704.2193.

Synthesis of Fmoc-(R)-m-bromo-phenylalanine, (R)-21

To a suspension of (SC,RN,RC)-15a (740 mg, 1.01 mmol) in methanol (10 mL) was added 3 N HCl (1.68 mL, 5.04 mmol), and the reaction mixture was heated at 50 °C for 1 h. Upon disappearance of the red color of the starting complex, the reaction mixture was concentrated to give a residue. To the residue were added water (10 mL) and ethyl acetate (10 mL) and then the phases were separated. The organic phase was washed with brine (10 mL), dried over sodium sulfate, and evaporated under vacuum to afford the recycle ligand (S)-4 (488 mg, 99.3%). The aqueous phase was concentrated to give crude AA (R)-20. The residue was dissolved in water (14 mL) and tetrahydrofuran (THF) (7 mL) to which EDTA disodium salt dihydrate (375 mg, 1.01 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was basified with sodium carbonate (214 mg, 2.02 mmol) and sodium bicarbonate (169 mg, 2.02 mmol). To this solution was added a solution of Fmoc-OSu (374 mg, 1.11 mmol) in THF (7 mL) and stirred at rt for 16 h. After evaporation of the organic solvents, the aqueous residue was acidified with 3 N HCl to pH 2 to give a precipitate. The precipitate was filtered and washed with water (20 mL) to afford crude (R)-21. The crude solid thus obtained was recrystallized from THF/IPE (1:1) and dried at 50 °C to afford (R)-21 (466 mg, 99.1%, 97.1% ee). The spectral data were found to be identical with the commercial enantiopure sample. 1H NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 2.85 (dd, J = 10.4, 13.7 Hz, 1H), 3.10 (dd, J = 4.4, 13.7 Hz, 1H), 4.02–4.33 (m, 4H), 7.14–7.56 (m, 8H), 7.57–7.77 (m, 3H), 7.88 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 36.1, 46.6, 55.4, 65.6, 120.1, 121.4, 125.1, 125.2, 127.0, 127.6, 128.2, 129.2, 130.2, 131.9, 140.6, 140.6, 141.0, 143.7, 143.7, 155.8, 172.9.

Synthesis of Fmoc-(R)-p-nitro-phenylalanine, (R)-24

To a suspension of (SC,RN,RC)-15f (5 g, 7.14 mmol) in methanol (60 mL) was added 3 N HCl (11.9 mL, 35.7 mmol), and the reaction mixture was heated at 50 °C for 1 h. Upon disappearance of the red color of the starting complex, the reaction mixture was concentrated to give a residue. To the residue were added water (25 mL) and ethyl acetate (50 mL) and then the phases were separated. The organic phase was washed with brine (10 mL), dried over sodium sulfate, and evaporated under vacuum to afford the recycle ligand (S)-4 (2.93 g, 84.1%). To the aqueous phase was added EDTA disodium salt dihydrate (2.66 g, 7.14 mmol), and the reaction mixture was basified with 48% sodium hydroxide to pH 13. After stirring at rt for 10 min, the solution was acidified with 12 N HCl to pH 5.5 to give a precipitate. The precipitate was filtered and washed with water (20 mL) to afford AA (R)-23 (1.30 g, 86.6%). The AA (R)-23 thus obtained was dissolved in water (50 mL) and THF (25 mL), and the reaction mixture was basified with sodium carbonate (1.51 g, 14.3 mmol) and sodium bicarbonate (1.20 g, 14.3 mmol). To this solution was added a solution of Fmoc-OSu (2.41 g, 7.14 mmol) in THF (25 mL) and stirred at rt for 16 h. After evaporation of the organic solvents, the aqueous residue was acidified with 3 N HCl to pH 2 to give a precipitate. The precipitate was filtered and washed with water (50 mL) to afford crude (R)-24. The crude solid thus obtained was recrystallized from THF/IPE (1:1) and dried at 50 °C to afford (R)-24 (2.59 g, 97.1%, 98.6% ee). The spectral data were found to be identical with the commercial enantiopure sample. 1H NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 3.00 (dd, J = 10.9, 13.7 Hz, 1H), 3.24 (dd, J = 4.4, 13.7 Hz, 1H), 4.02–4.37 (m, 4H), 7.28 (dddd, J = 1.0, 3.2, 7.4, 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.40 (ddd, J = 1.0, 7.4, 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.61 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 8.14 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 36.2, 46.6, 54.9, 65.6, 120.2, 123.3, 125.2, 127.1, 127.7, 130.5, 140.7, 140.7, 143.7, 143.8, 146.3, 146.5, 156.0, 172.9.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the IKERBASQUE, Basque Foundation for Science, and the Basque Government. We are also grateful to Servicios Generales de Investigación (SGIker, UPV/EHU) for HRMS analyses.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b01424.

Chiral high-performance liquid chromatography analysis data, copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra, and modified precipitation of complex 15f (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Henninot A.; Collins J. C.; Nuss J. M. The Current State of Peptide Drug Discovery: Back to the Future?. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 1382–1414. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Blaskovich M. A. T. Unusual Amino Acids in Medicinal Chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 10807–10836. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Soloshonok V. A.; Izawa K.. Asymmetric Synthesis and Application of α-Amino Acids; ACS Symposium Series #1009; Oxford University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- For the definition of tailor-made amino acids, see:Soloshonok V. A.; Cai C.; Hruby V. J.; Van Meervelt L. Asymmetric Synthesis of Novel Highly Sterically Constrained (2S,3S)-3-Methyl-3-trifluoromethyl- and (2S,3S,4R)-3-Trifluoromethyl-4-methylpyroglutamic Acids. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 12045–12058. 10.1016/s0040-4020(99)00710-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Gante J. Peptidomimetics-Tailored Enzyme Inhibitors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1994, 33, 1699–1720. 10.1002/anie.199416991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Hruby V. J.; Li G.; Haskell-Luevano C.; Shenderovich M. Design of Peptides, Proteins, and Peptidomimetics in Chi Space. Biopolymers 1997, 43, 219–266. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hruby V.; Balse P. Conformational and Topographical Considerations in Designing Agonist Peptidomimetics from Peptide Leads. Curr. Med. Chem. 2000, 7, 945–970. 10.2174/0929867003374499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Vagner J.; Qu H.; Hruby V. J. Peptidomimetics, a Synthetic Tool of Drug Discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008, 12, 292–296. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Cai M.; Cai C.; Mayorov A. V.; Xiong C.; Cabello C. M.; Soloshonok V. A.; Swift J. R.; Trivedi D.; Hruby V. J. Biological and conformational study of β-substituted prolines in MT-II template: steric effects leading to human MC5 receptor selectivity*. J. Pept. Res. 2004, 63, 116–131. 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2003.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ma J. S. Unnatural Amino Acids in Drug Discovery. Chim. Oggi 2003, 21, 65–68. [Google Scholar]; b Hodgson D. R. W.; Sanderson J. M. The Synthesis of Peptides and Proteins Containing Non-Natural Amino Acids. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004, 33, 422–430. 10.1039/b312953p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sato T.; Izawa K.; Aceña J. L.; Liu H.; Soloshonok V. A. Tailor-Made α-Amino Acids in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Synthetic Approaches to (1R,2S)-1-Amino-2-vinylcyclopropane-1-carboxylic Acid (Vinyl-ACCA). Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 2757–2774. 10.1002/ejoc.201600112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Sorochinsky A. E.; Aceña J. L.; Moriwaki H.; Sato T.; Soloshonok V. A. Asymmetric synthesis of α-amino acids via homologation of Ni(II) complexes of glycine Schiff bases; Part 1: alkyl halide alkylations. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 691–718. 10.1007/s00726-013-1539-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lovering F. Escape from Flatland 2: Complexity and Promiscuity. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 515–519. 10.1039/c2md20347b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Fosgerau K.; Hoffmann T. Peptide Therapeutics: Current Status and Future Directions. Drug Discovery Today 2015, 20, 122–128. 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Craik D. J.; Fairlie D. P.; Liras S.; Price D. The Future of Peptide-Based Drugs. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2013, 81, 136–147. 10.1111/cbdd.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wang S.; Wang Y.; Wang J.; Sato T.; Izawa K.; Soloshonok V. A.; Liu H. The Second-generation of Highly Potent Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) NS3/4A Protease Inhibitors: Evolutionary Design Based on Tailor-made Amino Acids, Synthesis and Major Features of Bio-activity. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 4493–4554. 10.2174/1381612823666170522122424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mandell D. J.; Lajoie M. J.; Mee M. T.; Takeuchi R.; Kuznetsov G.; Norville J. E.; Gregg C. J.; Stoddard B. L.; Church G. M. Biocontainment of Genetically Modified Organisms by Synthetic Protein Design. Nature 2015, 518, 55–60. 10.1038/nature14121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rovner A. J.; Haimovich A. D.; Katz S. R.; Li Z.; Grome M. W.; Gassaway B. M.; Amiram M.; Patel J. R.; Gallagher R. R.; Rinehart J.; Isaacs F. J. Recoded Organisms Engineered to Depend on Synthetic Amino Acids. Nature 2015, 518, 89–93. 10.1038/nature14095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a So S. M.; Kim H.; Mui L.; Chin J. Mimicking Nature to Make Unnatural Amino Acids and Chiral Diamines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 229–241. 10.1002/ejoc.201101073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Metz A. E.; Kozlowski M. C. Recent Advances in Asymmetric Catalytic Methods for the Formation of Acyclic α,α-Disubstituted α-Amino Acids. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 1–7. 10.1021/jo502408z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c He G.; Wang B.; Nack W. A.; Chen G. Syntheses and Transformations of α-Amino Acids via Palladium-Catalyzed Auxiliary-Directed sp3 C-H Functionalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 635–645. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sorochinsky A. E.; Aceña J. L.; Moriwaki H.; Sato T.; Soloshonok V. Asymmetric synthesis of α-amino acids via homologation of Ni(II) complexes of glycine Schiff bases. Part 2: Aldol, Mannich addition reactions, deracemization and (S) to (R) interconversion of α-amino acids. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 1017–1033. 10.1007/s00726-013-1580-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Aceña J. L.; Sorochinsky A. E.; Soloshonok V. Asymmetric synthesis of α-amino acids via homologation of Ni(II) complexes of glycine Schiff bases. Part 3: Michael addition reactions and miscellaneous transformations. Amino Acids 2014, 46, 2047–2073. 10.1007/s00726-014-1764-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Soloshonok V.; Sorochinsky A. Practical Methods for the Synthesis of Symmetrically α,α-Disubstituted α-Amino Acids. Synthesis 2010, 2319–2344. 10.1055/s-0029-1220013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grygorenko O. O.; Biitseva A. V.; Zhersh S. Amino Sulfonic Acids, Peptidosulfonamides and Other Related Compounds. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 1355–1421. 10.1016/j.tet.2018.01.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turcheniuk K. V.; Kukhar V. P.; Röschenthaler G.-V.; Aceña J. L.; Soloshonok V. A.; Sorochinsky A. E. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Fluorinated Aminophosphonates and Aminophosphonic Acids. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 6693–6716. 10.1039/c3ra22891f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kukhar V. P.; Sorochinsky A. E.; Soloshonok V. A. Practical synthesis of fluorine-containing α- and β-amino acids: recipes from Kiev, Ukraine. Future Med. Chem. 2009, 1, 793–819. 10.4155/fmc.09.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Aceña J. L.; Sorochinsky A. E.; Moriwaki H.; Sato T.; Soloshonok V. A. Synthesis of fluorine-containing α-amino acids in enantiomerically pure form via homologation of Ni(II) complexes of glycine and alanine Schiff bases. J. Fluorine Chem. 2013, 155, 21–38. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2013.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Sorochinsky A.; Mikami K.; Fustero S.; Sánchez-Roselló M.; Aceña J.; Soloshonok V. Synthesis of Fluorinated β-Amino Acids. Synthesis 2011, 3045–3079. 10.1055/s-0030-1260173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Bravo P.; Farina A.; Kukhar V. P.; Markovsky A. L.; Meille S. V.; Soloshonok V. A.; Sorochinsky A. E.; Viani F.; Zanda M.; Zappalà C. Stereoselective Additions of α-Lithiated Alkyl-p-tolylsulfoxides toN-PMP(fluoroalkyl)aldimines. An Efficient Approach to Enantiomerically Pure Fluoro Amino Compounds. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 3424–3425. 10.1021/jo970004v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Soloshonok V. A.; Kirilenko A. G.; Kukhar’ V. P.; Resnati G. Transamination of fluorinated β-keto carboxylic esters. A biomimetic approach to β-polyfluoroalkyl-β-amino acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 3621–3624. 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)73652-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Shibata N.; Nishimine T.; Shibata N.; Tokunaga E.; Kawada K.; Kagawa T.; Sorochinsky A. E.; Soloshonok V. A. Organic Base-catalyzed Stereodivergent Synthesis of (R)- and (S)-3-Amino-4,4,4-trifluorobutanoic Acids. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 4124–4126. 10.1039/c2cc30627a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Röschenthaler G.-V.; Kukhar V. P.; Kulik I. B.; Belik M. Y.; Sorochinsky A. E.; Rusanov E. B.; Soloshonok V. A. Asymmetric Synthesis of Phosphonotrifluoroalanine and Its Derivatives using N-tert-Butanesulfinyl Imine Derived from Fluoral. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 539–542. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.11.096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Turcheniuk K. V.; Poliashko K. O.; Kukhar V. P.; Rozhenko A. B.; Soloshonok V. A.; Sorochinsky A. E. Efficient asymmetric synthesis of trifluoromethylated β-aminophosphonates and their incorporation into dipeptides. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 11519–11521. 10.1039/c2cc36702e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Soloshonok V. A.; Belokon Y. N.; Kuzmina N. A.; Maleev V. I.; Svistunova N. Y.; Solodenko V. A.; Kukhar V. P. Asymmetric synthesis of phosphorus analogues of dicarboxylic α-amino acids. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1992, 1525–1529. 10.1039/p19920001525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Soloshonok V. A.; Kirilenko A. G.; Fokina N. A.; Kukhar V. P.; Galushko S. V.; Švedas V. K.; Resnati G. Chemo-enzymatic approach to the synthesis of each of the four isomers of α-alkyl-β-fluoroalkyl-substituted β-amino acids. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1994, 5, 1225–1228. 10.1016/0957-4166(94)80163-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Soloshonok V. A.; Tang X.; Hruby V. J.; Meervelt L. V. Asymmetric Synthesis of α,β-Dialkyl-α-phenylalanines via Direct Alkylation of a Chiral Alanine Derivative with Racemic α-Alkylbenzyl Bromides. A Case of High Enantiomer Differentiation at Room Temperature. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 341–343. 10.1021/ol000330o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Qiu W.; Gu X.; Soloshonok V. A.; Carducci M. D.; Hruby V. J. Stereoselective Synthesis of Conformationally Constrained Reverse Turn Dipeptide Mimetics. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 145–148. 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)01864-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ueki H.; Yasumoto M.; Soloshonok V. A. Rational application of self-disproportionation of enantiomers via sublimation-a novel methodological dimension for enantiomeric purifications. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2010, 21, 1396–1400. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.04.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Sorochinsky A. E.; Katagiri T.; Ono T.; Wzorek A.; Aceña J. L.; Soloshonok V. A. Optical Purifications via Self-Disproportionation of Enantiomers by Achiral Chromatography: Case Study of a Series of α-CF3-containing Secondary Alcohols. Chirality 2013, 25, 365–368. 10.1002/chir.22180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Suzuki Y.; Han J.; Kitagawa O.; Aceña J. L.; Klika K. D.; Soloshonok V. A. A Comprehensive Examination of the Self-Disproportionation of Enantiomers (SDE) of Chiral Amides via Achiral, Laboratory-Routine, Gravity-Driven Column Chromatography. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 2988–2993. 10.1039/c4ra13928c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For other types of ligands possessing axial chirality, see:; a Takeda R.; Kawamura A.; Kawashima A.; Sato T.; Moriwaki H.; Izawa K.; Akaji K.; Wang S.; Liu H.; Aceña J. L.; Soloshonok V. A. Chemical Dynamic Kinetic Resolution andS/R Interconversion of Unprotected α-Amino Acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 12214–12217. 10.1002/anie.201407944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jörres M.; Aceña J. L.; Soloshonok V. A.; Bolm C. Asymmetric Carbon-Carbon Bond Formation under Solventless Conditions in Ball Mills. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 1265–1269. 10.1002/cctc.201500102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ueki H.; Ellis T. K.; Martin C. H.; Soloshonok V. A. Efficient Large-Scale Synthesis of Picolinic Acid-Derived Nickel(II) Complexes of Glycine. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 1954–1957. 10.1002/ejoc.200200688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ueki H.; Ellis T. K.; Martin C. H.; Boettiger T. U.; Bolene S. B.; Soloshonok V. A. Improved Synthesis of Proline-Derived Ni(II) Complexes of Glycine: Versatile Chiral Equivalents of Nucleophilic Glycine for General Asymmetric Synthesis of α-Amino Acids. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 7104–7107. 10.1021/jo0301494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ellis T. K.; Martin C. H.; Ueki H.; Soloshonok V. A. Efficient, practical synthesis of symmetrically α,α-disubstituted α-amino acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 1063–1066. 10.1016/s0040-4039(02)02719-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Soloshonok V. A.; Tang X.; Hruby V. J. Large-scale asymmetric synthesis of novel sterically constrained 2′,6′-dimethyl- and α,2′,6′-trimethyltyrosine and -phenylalanine derivatives via alkylation of chiral equivalents of nucleophilic glycine and alanine. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 6375–6382. 10.1016/s0040-4020(01)00504-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Wang J.; Lin D.; Zhou S.; Ding X.; Soloshonok V. A. Asymmetric Synthesis of Sterically and Electronically Demanding Linear ω-Trifluoromethyl Containing Amino Acids via Alkylation of Chiral Equivalents of Nucleophilic Glycine and Alanine. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 684–687. 10.1021/jo102031b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yamada T.; Okada T.; Sakaguchi K.; Ohfune Y.; Ueki H.; Soloshonok V. A. Efficient Asymmetric Synthesis of Novel 4-Substituted and Configurationally Stable Analogues of Thalidomide. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5625–5628. 10.1021/ol0623668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Soloshonok V. A.; Cai C.; Hruby V. J. (S)- or (R)-3-(E-Enoyl)-4-phenyl-1,3- oxazolidin-2-ones: Ideal Michael Acceptors To Afford a Virtually Complete Control of Simple and Face Diastereoselectivity in Addition Reactions with Glycine Derivatives. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 747–750. 10.1021/ol990402f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yamada T.; Sakaguchi K.; Shinada T.; Ohfune Y.; Soloshonok V. A. Efficient asymmetric synthesis of the functionalized pyroglutamate core unit common to oxazolomycin and neooxazolomycin using Michael reaction of nucleophilic glycine Schiff base with α,β-disubstituted acrylate. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2008, 19, 2789–2795. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2008.11.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Soloshonok V. A.; Kukhar V. P.; Galushko S. V.; Svistunova N. Y.; Avilov D. V.; Kuz’mina N. A.; Raevski N. I.; Struchkov Y. T.; Pysarevsky A. P.; Belokon Y. N. General method for the synthesis of enantiomerically pure β-hydroxy-α-amino acids, containing fluorine atoms in the side chains. Case of stereochemical distinction between methyl and trifluoromethyl groups. X-Ray crystal and molecular structure of the nickel(II) complex of (2S,3S)-2(trifluoromethyl)threonine. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1993, 3143–3155. 10.1039/p19930003143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Soloshonok V. A.; Avilov D. V.; Kukhar’ V. P. Highly Diastereoselective Asymmetric Aldol Reactions of Chiral Ni(II)-Complex of Glycine with Alkyl Trifluoromethyl Ketones. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1996, 7, 1547–1550. 10.1016/0957-4166(96)00177-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Soloshonok V. A.; Avilov D. V.; Kukhar’ V. P.; Tararov V. I.; Savel’eva T. F.; Churkina T. D.; Ikonnikov N. S.; Kochetkov K. A.; Orlova S. A.; Pysarevsky A. P.; Struchkov Y. T.; Raevsky N. I.; Belokon’ Y. N. Asymmetric aldol reactions of chiral Ni(II)-complex of glycine with aliphatic aldehydes. Stereodivergent synthesis of syn-(2S)- and syn-(2R)-β-alkylserines. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1995, 6, 1741–1756. 10.1016/0957-4166(95)00220-j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Soloshonok V. A.; Avilov D. V.; Kukhar V. P.; Meervelt L. V.; Mischenko N. Highly Diastereoselective Aza-Aldol Reactions of a Chiral Ni(II) Complex of Glycine with Imines. An Efficient Asymmetric Approach to 3-perfluoroalkyl-2,3-diamino Acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 4671–4674. 10.1016/s0040-4039(97)00963-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kawamura A.; Moriwaki H.; Röschenthaler G.-V.; Kawada K.; Aceña J. L.; Soloshonok V. A. Synthesis of (2S,3S)-β-(trifluoromethyl)-α,β-diamino acid by Mannich addition of glycine Schiff base Ni(II) complexes to N-tert-butylsulfinyl-3,3,3-trifluoroacetaldimine. J. Fluorine Chem. 2015, 171, 67–72. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2014.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ellis T. K.; Hochla V. M.; Soloshonok V. A. Efficient Synthesis of 2-Aminoindane-2-carboxylic Acid via Dialkylation of Nucleophilic Glycine Equivalent. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 4973–4976. 10.1021/jo030065v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ellis T. K.; Martin C. H.; Ueki H.; Soloshonok V. A. Efficient, practical synthesis of symmetrically α,α-disubstituted α-amino acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 1063–1066. 10.1016/s0040-4039(02)02719-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Soloshonok V.; Boettiger T.; Bolene S. Asymmetric Synthesis of (2S,3S)- and (2R,3R)-α,β-Dialkyl-α-amino Acids via Alkylation of Chiral Nickel(II) Complexes of Aliphatic α-Amino Acids with Racemic α-Alkylbenzyl Bromides. Synthesis 2008, 2594–2602. 10.1055/s-2008-1067172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Yamamoto J.; Kawashima A.; Kawamura A.; Abe H.; Moriwaki H.; Shibata N.; Soloshonok V. A. Operationally Convenient and Scalable Asymmetric Synthesis of (2S )- and (2R )-α-(Methyl)cysteine Derivatives through Alkylation of Chiral Alanine Schiff Base NiII Complexes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 1931–1939. 10.1002/ejoc.201700018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kawashima A.; Xie C.; Mei H.; Takeda R.; Kawamura A.; Sato T.; Moriwaki H.; Izawa K.; Han J.; Aceña J. L.; Soloshonok V. A. Asymmetric synthesis of (1R,2S)-1-amino-2-vinylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid by sequential SN2-SN2′ dialkylation of (R)-N-(benzyl)proline-derived glycine Schiff base Ni(ii) complex. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 1051–1058. 10.1039/c4ra12658k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kawashima A.; Shu S.; Takeda R.; Kawamura A.; Sato T.; Moriwaki H.; Wang J.; Izawa K.; Aceña J. L.; Soloshonok V. A.; Liu H. Advanced Asymmetric Synthesis of (1R,2S)-1-Amino-2-vinylcyclopropanecarboxylic Acid by Alkylation/Cyclization of Newly Designed Axially Chiral Ni(II) Complex of Glycine Schiff Base. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 973–986. 10.1007/s00726-015-2138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Taylor S. M.; Yamada T.; Ueki H.; Soloshonok V. A. Asymmetric Synthesis of Enantiomerically Pure 4-Aminoglutamic Acids via Methylenedimerization of Chiral Glycine Equivalents with Dichloromethane under Operationally Convenient Conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 9159–9162. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.10.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Wang J.; Liu H.; Aceña J. L.; Houck D.; Takeda R.; Moriwaki H.; Sato T. Synthesis of bis-α,α′-amino acids through diastereoselective bis-alkylations of chiral Ni(ii)-complexes of glycine. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 4508–4515. 10.1039/c3ob40594j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Metrano A. J.; Miller S. J. Peptide-Catalyzed Conversion of Racemic Oxazol-5(4H)-ones into Enantiomerically Enriched α-Amino Acid Derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 1542–1554. 10.1021/jo402828f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b So S. M.; Moozeh K.; Lough A. J.; Chin J. Highly Stereoselective Recognition and Deracemization of Amino Acids by Supramolecular Self-Assembly. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 829–832. 10.1002/anie.201307410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Moozeh K.; So S. M.; Chin J. Catalytic Stereoinversion ofL-Alanine to DeuteratedD-Alanine. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 9381–9385. 10.1002/anie.201503616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Fanelli R.; Jeanne-Julien L.; René A.; Martinez J.; Cavelier F. Stereoselective synthesis of unsaturated α-amino acids. Amino Acids 2015, 47, 1107–1115. 10.1007/s00726-015-1934-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Schwieter K. E.; Johnston J. N. Enantioselective synthesis of d-α-amino amides from aliphatic aldehydes. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 2590–2595. 10.1039/c5sc00064e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Bull S.; Hutchby M.; Sedgwick A. Orthogonally Protected Schöllkopf’s Bis-lactim Ethers for the Asymmetric Synthesis of α-Amino Acid Derivatives and Dipeptide Esters. Synthesis 2016, 48, 2036–2049. 10.1055/s-0035-1561943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Wangweerawong A.; Hummel J. R.; Bergman R. G.; Ellman J. A. Preparation of Enantiomerically Pure Perfluorobutanesulfinamide and Its Application to the Asymmetric Synthesis of α-Amino Acids. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 1547–1557. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Schettini R.; Nardone B.; De Riccardis F.; Della Sala G.; Izzo I. Cyclopeptoids as Phase-Transfer Catalysts for the Enantioselective Synthesis of α-Amino Acids. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 7793–7797. 10.1002/ejoc.201403224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Morrill L. C.; Lebl T.; Slawin A. M. Z.; Smith A. D. Catalytic asymmetric α-amination of carboxylic acids using isothioureas. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 2088–2093. 10.1039/c2sc20171b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j Etxabe J.; Izquierdo J.; Landa A.; Oiarbide M.; Palomo C. Catalytic Enantioselective Synthesis of N,Cα,Cα-Trisubstituted α-Amino Acid Derivatives Using 1H-Imidazol-4(5H)-ones as Key Templates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 6883–6886. 10.1002/anie.201501275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Soloshonok V. A.; Ellis T. K.; Ueki H.; Ono T. Resolution/Deracemization of Chiral α-Amino Acids Using Resolving Reagents with Flexible Stereogenic Centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 7208–7209. 10.1021/ja9026055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sorochinsky A. E.; Ueki H.; Aceña J. L.; Ellis T. K.; Moriwaki H.; Sato T. Chemical approach for interconversion of (S)- and (R)-α-amino acids. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 4503–4507. 10.1039/c3ob40541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Soloshonok A. E.; Ueki H.; Aceña J. L.; Ellis T. K.; Moriwaki H.; Sato T.; Soloshonok V. A. Chemical deracemization and (S) to (R) interconversion of some fluorine-containing α-amino acids. J. Fluorine Chem. 2013, 152, 114–118. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2013.02.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhou S.; Wang J.; Chen X.; Aceña J. L.; Soloshonok V. A.; Liu H. Chemical Kinetic Resolution of Unprotected β-Substituted β-Amino Acids Using Recyclable Chiral Ligands. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7883–7886. 10.1002/anie.201403556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhou S.; Wang S.; Wang J.; Nian Y.; Peng P.; Soloshonok V. A.; Liu H. Configurationally Stable (S )- and (R )-α-Methylproline-Derived Ligands for the Direct Chemical Resolution of Free Unprotected β3 -Amino Acids. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 1821–1832. 10.1002/ejoc.201800120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Tessaro D.; Cerioli L.; Servi S.; Viani F.; D’Arrigo P. l-Amino Acid Amides via Dynamic Kinetic Resolution. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2333–2338. 10.1002/adsc.201100389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b D’Arrigo P.; Cerioli L.; Fiorati A.; Servi S.; Viani F.; Tessaro D. Naphthyl-l-α-amino Acids via Chemo-Enzymatic Dynamic Kinetic Resolution. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2012, 23, 938–944. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2012.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c D’Arrigo P.; Cerioli L.; Servi S.; Viani F.; Tessaro D. Synergy between Catalysts: Enzymes and Bases. DKR of Non-Natural Amino Acids Derivatives. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 1606–1616. 10.1039/c2cy20106b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Baxter S.; Royer S.; Grogan G.; Brown F.; Holt-Tiffin K. E.; Taylor I. N.; Fotheringham I. G.; Campopiano D. J. An Improved Racemase/Acylase Biotransformation for the Preparation of Enantiomerically Pure Amino Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 19310–19313. 10.1021/ja305438y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Yasukawa K.; Asano Y. Enzymatic Synthesis of Chiral Phenylalanine Derivatives by a Dynamic Kinetic Resolution of Corresponding Amide and Nitrile Substrates with a Multi-Enzyme System. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 3327–3332. 10.1002/adsc.201100923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ellis T. K.; Ueki H.; Yamada T.; Ohfune Y.; Soloshonok V. A. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of a New Generation of Modular Nucleophilic Glycine Equivalents for the Efficient Synthesis of Sterically Constrained α-Amino Acids. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 8572–8578. 10.1021/jo0616198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Soloshonok V. A.; Ueki H.; Ellis T. K.; Yamada T.; Ohfune Y. Application of modular nucleophilic glycine equivalents for truly practical asymmetric synthesis of β-substituted pyroglutamic acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 1107–1110. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.12.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Bergagnini M.; Fukushi K.; Han J.; Shibata N.; Roussel C.; Ellis T. K.; Aceña J. L.; Soloshonok V. A. NH-type of Chiral Ni(II) Complexes of Glycine Schiff Base: Design, Structural Evaluation, Reactivity and synthetic applications. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 1278–1291. 10.1039/c3ob41959b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Soloshonok V. A.; Ellis T. K. Design and Synthesis of a New Generation of ‘NH’-Ni(II) Complexes of Glycine Schiff Bases and their Unprecedented C-H vs. N-H Chemoselectivity in Alkyl Halide Alkylations and Michael Addition Reactions. Synlett 2006, 0533–0538. 10.1055/s-2006-926252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Takeda R.; Kawamura A.; Kawashima A.; Moriwaki H.; Sato T.; Aceña J. L.; Soloshonok V. A. Design and synthesis of (S)- and (R)-α-(phenyl)ethylamine-derived NH-type ligands and their application for the chemical resolution of α-amino acids. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 6239–6249. 10.1039/c4ob00669k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda R.; Kawamura A.; Kawashima A.; Sato T.; Moriwaki H.; Izawa K.; Abe H.; Soloshonok V. A. Second-order asymmetric transformation and its application for the practical synthesis of α-amino acids. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 4968–4972. 10.1039/c8ob00963e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanka L.; Iqbal K.; Schreiner P. R. The Lipophilic Bullet Hits the Targets: Medicinal Chemistry of Adamantane Derivatives. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 3516–3604. 10.1021/cr100264t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Jamison M. M.; Turner E. E. 84. The Inter-Relation of First- and Second-Order Asymmetric Transformations. J. Chem. Soc. 1942, 437–440. 10.1039/jr9420000437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Busch D. H. High Yield Resolution of Tris-(ethylenediamine)-cobalt(III) by a Second-order Asymmetric Process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77, 2747–2748. 10.1021/ja01615a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Faigl F.; Mátravölgyi B.; Holczbauer T.; Czugler M.; Madarász J. Resolution of 1-[2-Carboxy-6-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic Acid with Methyl (R)-2-Phenylglycinate, Reciprocal Resolution and Second Order Asymmetric Transformation. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2011, 22, 1879–1884. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2011.10.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Tsubaki K.; Miura M.; Morikawa H.; Tanaka H.; Kawabata T.; Furuta T.; Tanaka K.; Fuji K. Synthesis of Optically Active Oligonaphthalenes via Second-Order Asymmetric Transformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 16200–16201. 10.1021/ja038910e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Yamada K.-i.; Ishii R.; Nakagawa H.; Kawazura H. A Second-Order Asymmetric Transformation of Racemic 2-Hydroxymethyl[5]thiaheterohelicene into a Single Enantiomer upon Uptake by Bovine Serum Albumin. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1996, 7, 737–746. 10.1016/0957-4166(96)00069-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Donaldson W. A.; Shang L.; Rogers R. D. Reactivity of Tricarbonyl(pentadienyl)iron(1+) Cations: Preparation of an Optically Pure Tricarbonyl(diene)iron Complex via Second-Order Asymmetric Transformation. Organometallics 1994, 13, 6–7. 10.1021/om00013a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Smrcina M.; Lorenc M.; Hanus V.; Sedmera P.; Kocovsky P. Synthesis of Enantiomerically Pure 2,2′-Dihydroxy-1,1′-binaphthyl, 2,2′-Diamino-1,1′-binaphthyl, and 2-Amino-2′-hydroxy-1,1′-binaphthyl. Comparison of Processes Operating as Diastereoselective Crystallization and as Second Order Asymmetric Transformation. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 1917–1920. 10.1021/jo00032a055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houck D.; Luis Aceña J.; Soloshonok V. A. Alkylations of Chiral Nickel(II) Complexes of Glycine under Phase-Transfer Conditions. Helv. Chim. Acta 2012, 95, 2672–2679. 10.1002/hlca.201200536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.