Abstract

Solar light-activated photocatalyst nanoparticles (NPs) are promising environment-friendly low cost tools for water decontamination, but their dispersion in the environment must be minimized. Here, we propose the incorporation of TiO2-NPs (also in combination with graphene platelets) into highly biocompatible hydrogels as a promising approach for the production of photoactive materials for water treatment. We also propose a convenient fluorescence-based method to investigate the hydrogel photocatalytic activity in real time with a conventional fluorimeter. Kinetics analysis of the degradation profile of a target fluorescent model pollutant demonstrates that fast degradation occurs in the matrix bulk. Fluorescence anisotropy proved that small pollutant molecules diffuse freely in the hydrogel. Rheological and scanning electron microscopy characterization showed that the TiO2-NP incorporation does not significantly alter the hydrogel mechanical and morphological properties.

Introduction

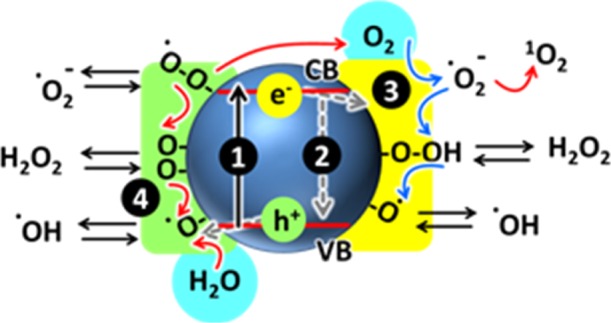

Pollution is one of the most important unsolved problems that nowadays affects our society. Photocatalytic degradation of water pollutants is a very attractive strategy to convert contaminants into harmless compounds by using eco-friendly materials.1 This approach is typically based on nanostructured photocatalysts, which are activated by solar light and use the absorbed energy to produce reactive chemical species, starting from water and oxygen (as schematized in Figure 1),2 and are able to degrade organic pollutants.3,4 Most effective photocatalysts are metal-oxide semiconductors (such as ZnO, FeO3, and WO35) and, in particular, titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NPs), in their anatase form, which have been widely used for a range of applications, including self-cleaning,5 surface sterilization,6 and air7 and water8 purification. Advantageous features of TiO2-NPs are the excellent stability in water, large-scale availability, and low cost. TiO2-NPs also show low toxicity,9,10 nevertheless the recent concerns about the still partially unpredictable risks related to the impact of nanomaterials on the environment and human health, as a defensive approach to minimize their dispersion in the environment.11,12

Figure 1.

Reactive oxygen species generated in the photocatalytic reduction and oxidation steps of oxygen and water. Absorption of light (1) causes the transition of electrons to the conduction band and the formation of holes in the valence band. Part of the produced charges undergo recombination (2), whereas others migrate to the surface where trapped electrons (3) participate in the reductive steps (blue arrows) and trapped holes (4) in the oxidative processes.

Incorporation of TiO2-NPs in highly biocompatible, macroscopic matrixes that preserve the photocatalytic activity of the semiconductor NPs is hence a fundamental challenge in the design of new materials for photocatalysis. As a fundamental feature, these matrixes should present (i) a high water content because water plays an essential role in the photocatalytic process (see Figure 1), (ii) good permeability to small molecules (pollutants), and (iii) good transparency to solar light.

In the last few years, we focused our research on the use of small pseudopeptides to form supramolecular hydrogels13−16 with specific properties, tailored to suit the applications of the produced hydrogels.17−21 Hence, we could obtain hydrogels of different strengths, pH values, and transparencies. These properties are not all necessarily needed for a given application. In this paper, we want to describe the preparation of transparent hydrogels and their application for photodegradation.22,23

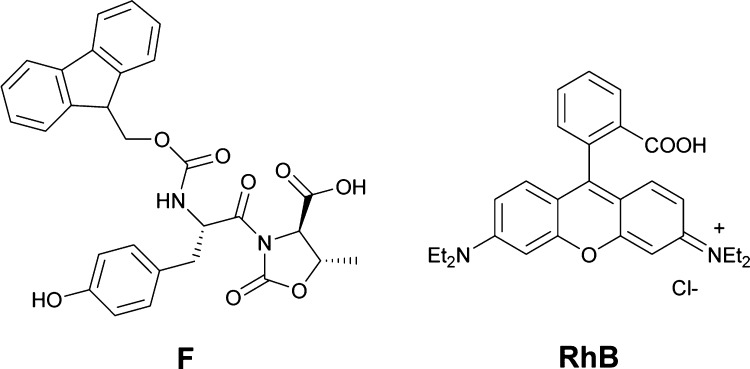

We recently reported the preparation of hydrogels by slow pH variation of a water solution of Fmoc-L-Tyr-D-Oxd-OH [Fmoc = fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl; Tyr = tyrosine; and D-Oxd = (4R,5S)-4-carboxy-5-methyl-oxazolidin-2-one] (F in Figure 2),24 and we compared their properties with the hydrogels formed with other gelators, among them Fmoc-Phe-Phe.25−28 We could demonstrate that the hydrogels prepared with gelator F, with pH variation as a trigger, reach a high transparency.24 Here, we describe the preparation of hydrogels, based on F, containing either TiO2-NPs or TiO2-NPs in combination with graphene platelets, and we demonstrate the ability to photodegrade a model pollutant compound (rhodamine B; RhB) upon ultraviolet (UV) irradiation. TiO2-NPs, in fact, absorb the UV part of the solar spectrum (λ < 380 nm)29 being the band gap between the conduction band (CB) and the valence band (VB),10 ΔE ≈ 3.25 eV (Figure 1). Integration of graphene in the photocatalytic TiO2 platform was also investigated to check the effect of graphene platelets on the hydrogel properties because carbon nanomaterials,30 such as nanotubes,31 carbon dots,32 graphene oxide,33 and reduced graphene oxide,34,35 have been reported to increase the photocatalytic performances of TiO2-NPs.

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of gelator F and rhodamine RhB.

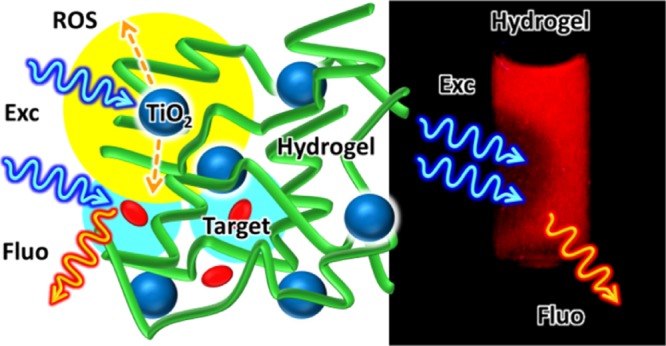

We would like to stress that different from other systems where TiO2-NPs36,37 can be activated by sunlight only on the surface of the exposed material (e.g., TiO2 photocatalyst embedded in cementitious materials5,38−40), in our photocatalytic hydrogels, light penetrates inside the matrix.

To demonstrate this outcome, we developed a new real-time fluorescence-based method for investigating the photocatalytic activity inside the hydrogels. One original feature of this approach is that the photocatalyst irradiation and the target degradation detection can be performed simultaneously in a standard fluorimeter, as shown in Figure 2.

Results and Discussion

Hydrogel Preparation and Characterization

For the hydrogel preparation, we used the pH change method. This method relies upon the enhanced solubility of Fmoc-Tyr-Oxd-OH at basic pH, followed by a slow decrease of pH by the addition of glucono-δ-lactone.41 We prepared three different samples of hydrogels: (i) hydrogel 1 (H) contains only the gelator Fmoc-l-Tyr-d-Oxd-OH in 0.5% (w/w) concentration and glucono-δ-lactone; (ii) hydrogel 2 (H-T) contains the gelator in 0.5% concentration, TiO2-NPs (0.2 mg/mL), and glucono-δ-lactone; (iii) 3 (H-TG) is prepared following the same procedure used for 2 (H-T), but replacing TiO2-NPs with TiO2-NPs/graphene.42

Before testing the hydrogels based on Fmoc-L-Tyr-D-Oxd-OH for the photocatalytic applications, we investigated the effect of TiO2-NPs or TiO2-NPs/graphene on their mechanical and morphological characteristics. Rheological analyses have been performed to evaluate the viscoelastic properties of hydrogels 1 (H), 2 (H-T), and 3 (H-TG) in terms of storage and loss moduli (G′ and G″, respectively) (Table 1and Figures S1 and S2).

Table 1. Storage Moduli (G′) and Loss Moduli (G″) of Hydrogels 1 (H), 2 (H-T), and 3 (H-TG).

| hydrogel | G′ (Pa) | G″ (Pa) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (H) | 1370 | 90 |

| 2(H-T) | 1055 | 63 |

| 3(H-TG) | 556 | 46 |

Although the hydrogels are characterized by a “solidlike” behavior, that is, the storage modulus is approximately an order of magnitude higher than the loss component, these hydrogels do not show very high G′ values because of the very low concentration of the gelator, required for obtaining good transparency. The results also pointed out that although the introduction of TiO2-NPs or TiO2-NPs/graphene partially affects the hydrogel properties, as in both cases, G′ decreases. This effect is more evident for hydrogel 3 (H-TG). Nevertheless, frequency sweep analysis (Figure S2) pointed out that for all obtained hydrogels, both G′ and G″ were almost independent of the frequency in the range from 0.1 to 100 rad·s–1 (always with G′ > G″), confirming the “solidlike” rheological behavior of the hydrogels and hence the stability of the hydrogel structure required for the photocatalytic application.

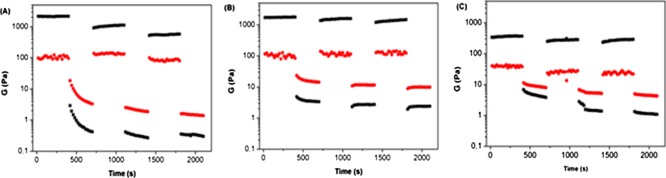

Step-strain experiments were performed to check the thixotropic behavior of 1 (H), 2 (H-T), and 3 (H-TG) on the molecular level. Strain values within and above the LVE (linear viscoelastic range) region were consecutively applied to the hydrogels, which lose their “solidlike” behavior (G′ < G″) when the strain is applied above their LVE region and quickly go back to a “solidlike” state (G′ > G″) if the strain is applied in the LVE region of the hydrogels (Figure 3). The three hydrogels show a thixotropic behavior, even though the G′ and G″ values of the graphene-doped hydrogel 3 (H-TG) are lower than the 1 (H) and 2 (H-T)G′ and G″ values.

Figure 3.

Values of storage moduli G′ (black) and loss moduli G″ (red) recorded during a step-strain experiment performed on (A) hydrogel 1 (H), (B) hydrogel 2 (H-T), and (C) hydrogel 3 (H-TG).

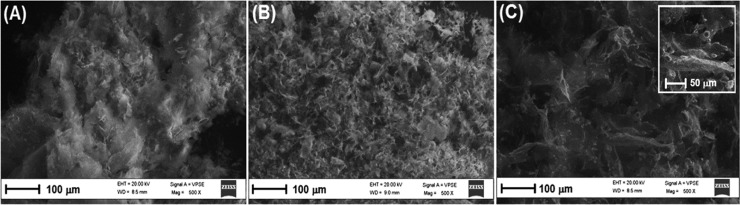

More information on the nature of hydrogels 1 (H), 2 (H-T), and 3 (H-TG) was obtained by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of the corresponding aerogels obtained by freeze-drying these samples (Figure 4). These aerogels show a different morphology, but they are all characterized by complex patterns with a rough orientation. Moreover, in aerogel 3 (H-TG) (Figure 4C and magnification), we can notice the presence of some small aggregates responsible for the formation of a less homogeneous hydrogel, in agreement with the results obtained from the rheological experiments.

Figure 4.

(A) SEM image of a sample of aerogel obtained by freeze-drying a sample of hydrogels 1 (H). (B) SEM image of a sample of aerogel obtained by freeze-drying a sample of hydrogels 2 (H-T). (C) SEM image of a sample of aerogel obtained by freeze-drying a sample of hydrogels and 3 (H-TG) prepared with Fmoc-L-Tyr-D-Oxd-OH 0.5% concentration. In the inset, a magnification view of aerogel film fragments.

Photodegradation Experiments

As mentioned, here, we propose an experimental approach based on fluorescence detection for investigating the photodegradation of a target molecule in the gel. As a main difference with respect to other methods based on fluorescence, we propose to use the same excitation beam and the same excitation wavelength for both photoactivating the photocatalyst TiO2 and exciting the target fluorophore RhB (see Figure 2). As a main advantage, this approach allows the continuous real-time detection of the target dye concentration during the process using a conventional fluorimeter equipped with a 150 W xenon lamp as an excitation source.

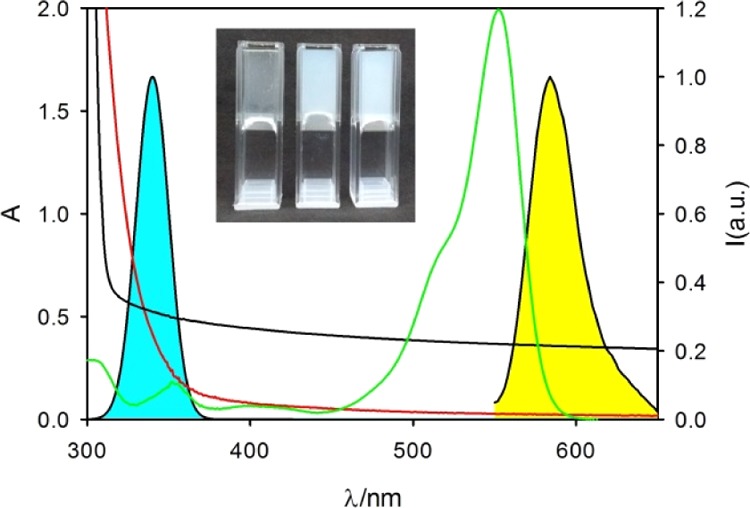

To select a suitable irradiation wavelength, we analyzed the absorption spectra of hydrogel 1 (H) of the TiO2-NPs (0.2 mg/mL) and RhB (1.0 μM) in a cuvette with a 0.5 cm optical path (spectra are shown in Figure 5). These spectra demonstrate that it is possible to excite simultaneously the TiO2-NPs and RhB upon irradiation in the UV spectral region when they are incorporated in the hydrogel (as sketched in Figure 2).

Figure 5.

Absorption spectrum of hydrogel 1 (H) (black line) of the TiO2 NPs (0.2 mg/mL, red line) and RhB (×20, 1 μM, green line). Fluorescence spectrum of RhB (filled yellow) and spectrum of the irradiation source (filled cyan). Inset: photographs of samples of hydrogels 1 (H), 2 (H-T), and 3 (H-TG) (from left to right, respectively) prepared with gelator Fmoc-L-Tyr-D-Oxd-OH in 0.5% concentration.

In fact, as foreseen, the hydrogel presents an edge of absorption around 310 nm because of the characteristic absorption spectra of the Fmoc chromophore26 that is present in the gelator structure.10,43,44 The hydrogel transmittance is T > 60% for wavelength λ > 320 nm, and hence the photocatalyst TiO2-NPs incorporated in the hydrogel in 1 (H) can be efficiently excited at 340 ± 10 nm using the fluorimeter excitation beam as an irradiation source (the spectral profile is shown in Figure 5).

Additionally, under these excitation conditions, RhB absorbs a minor fraction of the excitation light, and its fluorescence can be exploited as a diagnostic signal to follow the photodegradation of this dye during the photocatalytic experiments.

To investigate the TiO2 photocatalytic activity in the hydrogel, we prepared three samples like 1 (H), 2 (H-T), and 3 (H-TG), all containing a small concentration (1.0 μM) of RhB. For clarity, these samples will be referred as 4 (HR), 5 (HR-T), and 6 (HR-TG). Hydrogel rheological properties were not affected by the presence of small concentrations of RhB (1.0 μM) in the hydrogels.

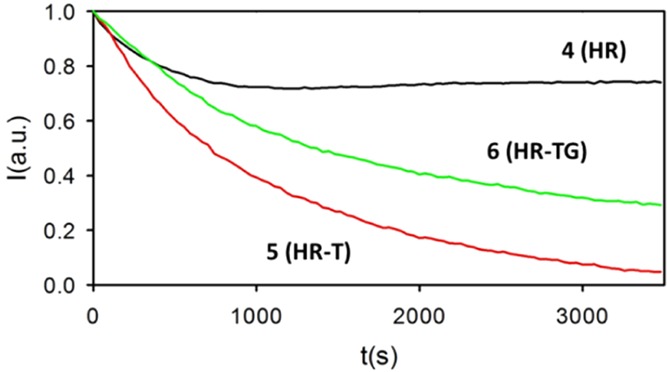

Results, reported in Figure 6, show that there is a strong decrease in RhB emission during the first hour of irradiation in the case of 5 (HR-T) and 6 (HR-TG). By contrast, in the reference hydrogel 4 (HR), the fluorescence signal decreases only by about 20% during the first 10 min (600 s), and then it reaches a plateau.45,46 Hence, as the fluorescence intensity is proportional to the fluorophore concentration, under these experimental conditions,47,48 we can gather that after 60 min of irradiation, the RhB concentration in the reference sample 4 (HR) is still 80% of the initial one, whereas the dye is completely degraded in the TiO2-containing sample 5 (HR-T) and a residual 25% survived in 6 (HR-TG). These results clearly demonstrate that (i) the TiO2-NPs photodecompose efficiently in RhB, but (ii) the introduction of graphene in hydrogel 6 (HR-TG) leads to a photoactivity decrease of TiO2-NPs, in contrast with what was observed in other matrixes.49

Figure 6.

Fluorescence intensity at 585 nm of RhB as a function of irradiation time (λexc = 340 nm) in sample 4 (HR), 5 (HR-T), and 6 (HR-TG).

Going into more detail, a simple parameter suitable to quantify the rate of the photodegradation process is the half-life t1/2, which is defined as the irradiation time at which the concentration value of the reactant (RhB) becomes half of the initial one. The half-life t1/2 of RhB corresponds to 12 and 23 min of irradiation for 5 (HR-T) and 6 (HR-TG), respectively.

To go into more details of the photodegradation kinetics, we analyzed the kinetics traces of Figure 6 according to a (pseudo) first-order model (see the Supporting Information). From the data analysis, we obtain values of the rate constant k = 8.0 ± 0.1 × 10–4 s–1 and k = 4.0 ± 0.1 × 10–4 s–1 for 5 (HR-T) and 6 (HR-TG), respectively. This result further confirms that the presence of graphene in the hydrogel apparently causes a decrease in the TiO2-NP photocatalytic activity. Indeed, SEM and rheological analyses clearly indicate that graphene affects the matrix morphology and causes a homogeneity decrease of the TiO2-NP dispersion (see the Supporting Information): this alteration is the actual reason for the decreased photocatalytic activity of 6 (HR-TG) when compared to 5 (HR-T).

As far as the mechanism of photodegradation is concerned, the observed (pseudo) first-order kinetics is consistent with the Langmuir–Hinshelwood model, which is the most representative in describing the kinetic degradation of xanthene dyes as RhB in heterogeneous photocatalysis. This model takes into consideration the contribution of both dye adsorption on the photocatalyst surface and dye diffusion.50

In view of future applications, it is very important to understand whether, in the hydrogel, the target molecules RhB can freely diffuse or they are bound either to the gelator fibers or to the TiO2-NPs. Free diffusion of the pollutant moiety is in fact essential for the development of a material suitable for continuous recyclable materials for water decontamination.

We hence investigated the interactions between the target dye molecules and the microenvironment by steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopies, using fluorescence anisotropy to measure the local mobility of RhB in 4 (HR), 5 (HR-T), and 6 (HR-TG).

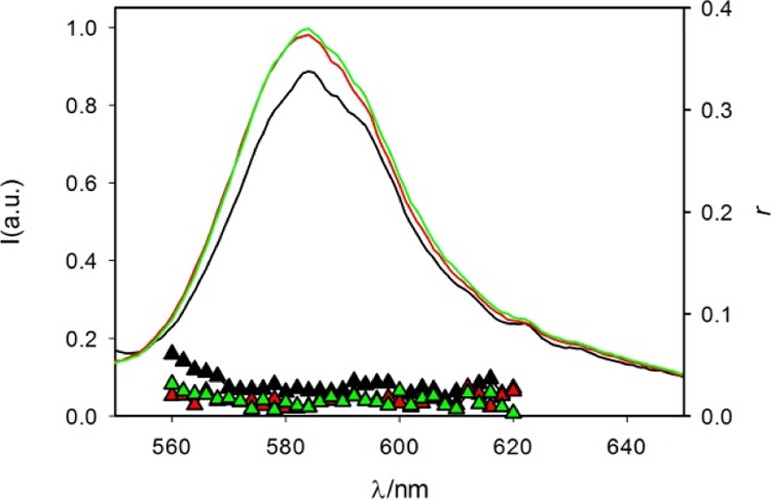

Quenching of RhB fluorescence has been reported to occur upon absorption on TiO2 or onto the honeycomb carbon structure of graphene.51,52 Hence, we recorded and compared the fluorescence emission and excitation spectra of RhB (λexc = 530 nm) of 4 (HR), 5 (HR-T), and 6 (HR-TG). On the basis of the fluorescence spectra, shown in Figure 7, we concluded that no quenching of the fluorescence of RhB could be observed in 5 (HR-T) and 6 (HR-TG).

Figure 7.

Fluorescence spectra (λexc = 530 nm) of RhB in sample 4 (HR) (black line), 5 (HR-T) (red line), and 6 (HR-TG) (green line) and fluorescence anisotropy of the same samples: black, red, and green triangles, respectively.

This conclusion was further supported by time-resolved fluorescence measurements. Excited-state lifetimes were measured by time-correlated single photon counting. Fluorescence decays recorded for RhB in 4 (HR), 5 (HR-T), and 6 (HR-TG) were fitted with a single exponential model to give excited-state lifetimes of 3.4, 3.7, and 3.6 ns, respectively. These values match with the lifetime of the fluorophore in water solution, confirming that no quenching of the fluorescence of the target dye occurs in 4 (HR), 5 (HR-T), and 6 (HR-TG).48,53,54

As mentioned, fluorescence anisotropy (r, dimensionless) measurements allow to determine the rotational mobility of a fluorophore in a given environment. Values of r close to 0.4 were reported for rhodamine molecules in the case of strongly hindered rotation,55,56 whereas the same molecules have an r very close to 0 when free to diffuse in poorly viscous solvent such as water.

Fluorescence anisotropy spectra of RhB in 4 (HR), 5 (HR-T), and 6 (HR-TG) are shown in Figure 7 (triangles); in all three cases, the anisotropy around the maximum fluorescence is very low (0.02–0.03) and similar to the value measured in pure water. This result confirms that the dye molecules can diffuse fast in the hydrogel (hence, the diffusion time is much shorter than the excited-state lifetime) and are dissolved in the hydrogel water channels rather than adsorbed on the gelator fibers.

Conclusions

In this paper, we reported the incorporation of TiO2-NPs (also in combination with graphene platelets) into highly biocompatible hydrogels, whose properties have been analyzed by rheological and SEM analyses.

These hydrogels show a high water content and good transparency to solar light, and they degrade a pollutant model molecule with good efficiency upon semiconductor NP irradiation.

Interestingly, our experiments demonstrate that light penetrates inside the hydrogel and that photodegradation occurs in the bulk of the material. This important result was achieved by optimizing the composition and the methodology of production of the hydrogel to avoid sedimentation and segregation of the TiO2-NPs (as demonstrated by the SEM analysis).

We also proved that while photodegradation of the target molecule (pollutant model) efficiently occurs upon irradiation, the photogenerated reactive species does not alter the matrix properties: rheology of the hydrogel, in fact, is not modified either by the incorporation of the photocatalysts or upon their irradiation.

Finally, we investigated the actual mobility of the pollutant molecules in the hydrogel on the microscopic level by steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy spectroscopies. Our results demonstrated that these molecules are not absorbed either on the hydrogel fibers or on the TiO2-NPs, suggesting that pollutant molecules are rather solubilized in the hydrogel water channel. This result is very important in view of the development of photocatalytic water-permeable materials for continuous decontamination of water in fluxing systems.

Experimental Section

Materials

All chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, VWR or Iris Biotech and were used as received. Acetonitrile was distilled under an inert atmosphere before use. Milli-Q water (Millipore, resistivity = 18.2 mΩ·cm) was used throughout.

Synthesis of Fmoc-L-Tyr-D-Oxd-OH

The compound was synthesized from D-Thr and Fmoc-L-Tyr(t-Bu)-OH following a multistep procedure in solution, reported in ref (24).

Hydrogel Preparation

A portion of Fmoc-L-Tyr-D-Oxd-OH (5 mg) was placed in a test tube (diameter: 8 mm); then Milli-Q water (0.97 mL) and a 1 M aqueous NaOH (1.3 equiv) were added; and the mixture was stirred until sample dissolution. Finally, we added 1.4 equiv of glucono-δ-lactone, and the mixture was left still for 16 h at room temperature. For more details, see Scheme S1.

Aerogel Preparation

Some samples of hydrogels 1–3 were freeze-dried using a BENCHTOP Freeze Dry System LABCONCO 7740030 with the following procedure: The hydrogel was prepared into an Eppendorf test tube at room temperature. After 16 h, the samples were deepened in liquid nitrogen for 10 min and then freeze-dried for 24 h in vacuo (0.2 mBar) at −50 °C.

Hydrogel Characterization

Morphological Analysis

Scanning electron micrographs of the samples were recorded using a Zeiss EP EVO 50 field emission gun scanning electron microscope. Conditions: EHT = 20 keV – variable pressure: 100 Pa—images in secondary electrons.

Rheology

Rheology experiments were carried out on an Anton Paar rheometer MCR 102 using parallel plate configuration (25 mm diameter). Experiments were performed at a constant temperature of 23 °C controlled by the integrated Peltier system and a Julabo AWC100 cooling system.

Ultraviolet–Visible (UV–Vis) Absorption Spectra

UV–vis absorption spectra (range 200–800 nm) were collected by using an optical path of 0.5 cm cuvette at 25 with a Cary 300 UV–vis double beam spectrophotometer, having an empty cuvette as a reference.

Steady-State and Time-Resolved Fluorescence Spectroscopies and Fluorescence Anisotropy

Fluorescence spectra were collected with an Edinburgh FLS920 fluorimeter equipped with a photomultiplier Hamamatsu R928P, and the samples were analyzed in disposable cuvettes with an optical path length of 0.5 cm. Emission spectra: λexc = 530 nm; λem: 540–700 nm. Excitation spectra: λexc = 330–600 nm, λem = 620 nm. Fluorescence anisotropy: λexc = 530 nm; λem: 550–650 nm.

Photodegradation Experiments

The kinetic analysis was carried on by continuously monitoring the degradation of RhB acquiring the fluorescence spectra with a Horiba FluoroMax-4 spectrofluorimeter upon excitation/irradiation at 340 nm (10 nm slits). Experimental parameters are reported in detail in Scheme S2.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (PRIN 2015 project 20157WW5EH) and Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna for the financial support. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 696656 (Graphene Flagship).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b01037.

Preparation and characterization of hydrogels 1 (H), 2 (H-T), 1 (H), 2 (H-T), 4 (HR), 5 (HR-T), and 6 (HR-TG), strain dependence and frequency dependence for hydrogels 1–3, emission spectra and excitation spectra of 1 (H), 2 (H-T), 4 (HR), 5 (HR-T), and 6 (HR-TG), comparison of the RhB emission lifetime decays in the ns timescale for 4 (HR), 5 (HR-T), and 6 (HR-TG), fluorescence anisotropy measurements for the samples 4 (HR), 5 (HR-T), and 6 (HR-TG) and hypothesis of the mechanism of the RhB degradation pathway (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Okesola B. O.; Smith D. K. Applying low-molecular weight supramolecular gelators in an environmental setting - self-assembled gels as smart materials for pollutant removal. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 4226–4251. 10.1039/c6cs00124f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosaka Y.; Nosaka A. Y. Generation and Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species in Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11302–11336. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong H.; Ouyang S.; Bi Y.; Umezawa N.; Oshikiri M.; Ye J. Nano-photocatalytic Materials: Possibilities and Challenges. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 229–251. 10.1002/adma.201102752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisch M.; Bahnemann D. Photokatalytisch aktiver Beton: Wie innovative Baustoffe einen Beitrag zum Abbau gefährlicher Luftschadstoffe leisten können. Beton—Stahlbetonbau 2017, 112, 47–53. 10.1002/best.201600506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y.; Huang J.; Cui Z.; Ge M.; Zhang K.-Q.; Chen Z.; Chi L. Recent Advances in TiO2-Based Nanostructured Surfaces with Controllable Wettability and Adhesion. Small 2016, 12, 2203–2224. 10.1002/smll.201501837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto S.; Bhushan B. Bioinspired Self-Cleaning Surfaces with Superhydrophobicity, Superoleophobicity, and Superhydrophilicity. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 671–690. 10.1039/c2ra21260a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mamaghani A. H.; Haghighat F.; Lee C.-S. Photocatalytic Oxidation Technology for Indoor Environment Air Purification: The State-of-the-Art. Appl. Catal., B 2017, 203, 247–269. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.10.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C.; Zhou W.; Liu H.; Liu Y.; Dionysiou D. D. Design and Fabrication of Microsphere Photocatalysts for Environmental Purification and Energy Conversion. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 287, 117–129. 10.1016/j.cej.2015.10.112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia T.; Kovochich M.; Brant J.; Hotze M.; Sempf J.; Oberley T.; Sioutas C.; Yeh J. I.; Wiesner M. R.; Nel A. E. Comparison of the Abilities of Ambient and Manufactured Nanoparticles to Induce Cellular Toxicity According to an Oxidative Stress Paradigm. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 1794–1807. 10.1021/nl061025k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M. R.; Martin S. T.; Choi W.; Bahnemann D. W. Environmental Applications of Semiconductor Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 69–96. 10.1021/cr00033a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vale G.; Mehennaoui K.; Cambier S.; Libralato G.; Jomini S.; Domingos R. F. Manufactured Nanoparticles in the Aquatic Environment-Biochemical Responses on Freshwater Organisms: A Critical Overview. Aquat. Toxicol. 2016, 170, 162–174. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djurišić A. B.; Leung Y. H.; Ng A. M. C.; Xu X. Y.; Lee P. K. H.; Degger N.; Wu R. S. S. Toxicity of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: Mechanisms, Characterization, and Avoiding Experimental Artefacts. Small 2014, 11, 26–44. 10.1002/smll.201303947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. K. Building bridges. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 162–163. 10.1038/nchem.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amabilino D. B.; Smith D. K.; Steed J. W. Supramolecular Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 2404–2420. 10.1039/c7cs00163k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalti M.; Dolci L. S.; Prodi L.; Zaccheroni N.; Stuart M. C. A.; van Bommel K. J. C.; Friggeri A. Energy Transfer from a Fluorescent Hydrogel to a Hosted Fluorophore. Langmuir 2006, 22, 2299–2303. 10.1021/la053015p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn M. E.; Gianneschi N. C. Enzyme-Directed Assembly and Manipulation of Organic Nanomaterials. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11814–11821. 10.1039/c1cc15220c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanna N.; Focaroli S.; Merlettini A.; Gentilucci L.; Teti G.; Falconi M.; Tomasini C. Thixotropic Peptide-Based Physical Hydrogels Applied to Three-Dimensional Cell Culture. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 2374–2381. 10.1021/acsomega.7b00322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasini C.; Zanna N. Oxazolidinone-Containing Pseudopeptides: Supramolecular Materials, Fibers, Crystals, and Gels. Biopolymers 2017, 108, e22898 10.1002/bip.22898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanna N.; Merlettini A.; Tomasini C. Self-Healing Hydrogels Triggered by Amino Acids. Org. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 1699–1704. 10.1039/c6qo00476h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castellucci N.; Falini G.; Angelici G.; Tomasini C. Formation of Gels in the Presence of Metal Ions. Amino Acids 2011, 41, 609–620. 10.1007/s00726-011-0908-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milli L.; Castellucci N.; Tomasini C. Turning Around theL-Phe-D-Oxd Moiety for a Versatile Low-Molecular-Weight Gelator. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 5954–5961. 10.1002/ejoc.201402787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C.; Lu J.; Qiu B.; Shen B.; Xing M.; Zhang J. Developing Stretchable and Graphene-Oxide-Based Hydrogel for the Removal of Organic Pollutants and Metal Ions. Appl. Catal., B 2018, 222, 146–156. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H.; Li Z.; Yang J. A Novel Composite Hydrogel for Adsorption and Photocatalytic Degradation of Bisphenol A by Visible Light Irradiation. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 1679–1690. 10.1016/j.cej.2017.11.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zanna N.; Merlettini A.; Tatulli G.; Milli L.; Focarete M. L.; Tomasini C. Hydrogelation Induced by Fmoc-Protected Peptidomimetics. Langmuir 2015, 31, 12240–12250. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b02780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liyanage W.; Vats K.; Rajbhandary A.; Benoit D. S. W.; Nilsson B. L. Multicomponent Dipeptide Hydrogels as Extracellular Matrix-Mimetic Scaffolds for Cell Culture Applications. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 11260–11263. 10.1039/c5cc03162a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao K.; Levin A.; Adler-Abramovich L.; Gazit E. Fmoc-Modified Amino Acids and Short Peptides: Simple Bio-Inspired Building Blocks for the Fabrication of Functional Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 3935–3953. 10.1039/c5cs00889a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orbach R.; Mironi-Harpaz I.; Adler-Abramovich L.; Mossou E.; Mitchell E. P.; Forsyth V. T.; Gazit E.; Seliktar D. The Rheological and Structural Properties of Fmoc-Peptide-Based Hydrogels: The Effect of Aromatic Molecular Architecture on Self-Assembly and Physical Characteristics. Langmuir 2012, 28, 2015–2022. 10.1021/la204426q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeburn J.; Mendoza-Cuenca C.; Cattoz B. N.; Little M. A.; Terry A. E.; Zamith Cardoso A.; Griffiths P. C.; Adams D. J. The effect of solvent choice on the gelation and final hydrogel properties of Fmoc-diphenylalanine. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 927–935. 10.1039/c4sm02256d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsebigler A. L.; Lu G.; Yates J. T. Jr Photocatalysis on TiO2 Surfaces: Principles, Mechanisms, and Selected Results. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 735–758. 10.1021/cr00035a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielski A.; Samorì P. Grapheneviasonication assisted liquid-phase exfoliation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 381–398. 10.1039/c3cs60217f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai K.; Peng T.; Ke D.; Wei B. Photocatalytic hydrogen generation using a nanocomposite of multi-walled carbon nanotubes and TiO2nanoparticles under visible light irradiation. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 125603. 10.1088/0957-4484/20/12/125603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M.; Ma X.; Chen X.; Sun Y.; Cui X.; Lin Y. A nanocomposite of carbon quantum dots and TiO2nanotube arrays: enhancing photoelectrochemical and photocatalytic properties. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 1120–1127. 10.1039/c3ra45474f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy K. R.; Hassan M.; Gomes V. G. Hybrid Nanostructures Based on Titanium Dioxide for Enhanced Photocatalysis. Appl. Catal., A 2015, 489, 1–16. 10.1016/j.apcata.2014.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han L.; Wang P.; Dong S. Progress in Graphene-Based Photoactive Nanocomposites as a Promising Class of Photocatalyst. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 5814–5825. 10.1039/c2nr31699d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A.; Chakrabarty S.; Kumari N.; Su W.-N.; Basu S. Visible-Light-Mediated Electrocatalytic Activity in Reduced Graphene Oxide-Supported Bismuth Ferrite. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 5946–5957. 10.1021/acsomega.8b00708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpone N.; Lawless D.; Khairutdinov R. Size Effects on the Photophysical Properties of Colloidal Anatase TiO2 Particles: Size Quantization versus Direct Transitions in This Indirect Semiconductor?. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 16646–16654. 10.1021/j100045a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kathiravan A.; Renganathan R. Effect of Anchoring Group on the Photosensitization of Colloidal TiO2 Nanoparticles with Porphyrins. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 331, 401–407. 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folli A.; Jakobsen U. H.; Guerrini G. L.; Macphee D. E. Rhodamine B Discolouration on TiO2 in the Cement Environment: A Look at Fundamental Aspects of the Self-Cleaning Effect in Concretes. J. Adv. Oxid. Technol. 2009, 12, 126–133. 10.1515/jaots-2009-0116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folli A.; Pade C.; Hansen T. B.; De Marco T.; Macphee D. E. TiO2 Photocatalysis in Cementitious Systems: Insights into Self-Cleaning and Depollution Chemistry. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 539–548. 10.1016/j.cemconres.2011.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zailan S. N.; Mahmed N.; Abdullah M. M. A.; Victor Sandu A.; Shahedan N. F.. Review on Characterization and Mechanical Performance of Self-Cleaning Concrete. In Engineering Technology International Conference 2016; Abdullah M. A. B., AbdRahim S. Z., Suandi M. E. M., Saad M. N. M., Ghazali M. F., Eds.; MATEC Web of Conferences, 2017; Vol. 97.

- Adams D. J.; Butler M. F.; Frith W. J.; Kirkland M.; Mullen L.; Sanderson P. A new method for maintaining homogeneity during liquid-hydrogel transitions using low molecular weight hydrogelators. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 1856–1862. 10.1039/b901556f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milli L.; Zanna N.; Merlettini A.; Di Giosia M.; Calvaresi M.; Focarete M. L.; Tomasini C. Pseudopeptide-Based Hydrogels Trapping Methylene Blue and Eosin Y. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22, 12106–12112. 10.1002/chem.201601861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiss W.; Thanh N. T. K.; Aveyard J.; Fernig D. G. Determination of Size and Concentration of Gold Nanoparticles from UV–Vis Spectra. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 4215–4221. 10.1021/ac0702084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapalis A.; Todorova N.; Giannakopoulou T.; Boukos N.; Speliotis T.; Dimotikali D.; Yu J. TiO 2 /graphene composite photocatalysts for NOx removal: A comparison of surfactant-stabilized graphene and reduced graphene oxide. Appl. Catal., B 2016, 180, 637–647. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zondervan R.; Kulzer F.; Kol’chenk M. A.; Orrit M. Photobleaching of Rhodamine 6G in Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) at the Ensemble and Single-Molecule Levels. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 1657–1665. 10.1021/jp037222e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm P.; Stephan D. Photodegradation of Rhodamine B in Aqueous Solution via SiO2@TiO2 Nano-Spheres. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2007, 185, 19–25. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2006.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montalti M.; Credi A.; Prodi L.; Gandolfi M. T.. Handbook of Photochemistry, 3rd ed.; CRC Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Genovese D.; Bonacchi S.; Juris R.; Montalti M.; Prodi L.; Rampazzo E.; Zaccheroni N. Prevention of Self-Quenching in Fluorescent Silica Nanoparticles by Efficient Energy Transfer. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 5965–5968. 10.1002/anie.201301155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl M.; Liu Y.; Yin Y. Composite Titanium Dioxide Nanomaterials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9853–9889. 10.1021/cr400634p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajeshwar K.; Osugi M. E.; Chanmanee W.; Chenthamarakshan C. R.; Zanoni M. V. B.; Kajitvichyanukul P.; Krishnan-Ayer R. Heterogeneous Photocatalytic Treatment of Organic Dyes in Air and Aqueous Media. J. Photochem. Photobiol., C 2008, 9, 171–192. 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2008.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao Y.-C.; Wu T.-F.; Wang Y.-S.; Hu C.-C.; Huang C. Evaluating the sensitizing effect on the photocatalytic decoloration of dyes using anatase-TiO2. Appl. Catal., B 2014, 148–149, 250–257. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti G.; Cantelli A.; Mazzaro R.; Ortolani L.; Morandi V.; Montalti M. Tracking Graphene by Fluorescence Imaging: A Tool for Detecting Multiple Populations of Graphene in Solution. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 8505–8511. 10.1039/c6nr02193j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalti M.; Battistelli G.; Cantelli A.; Genovese D. Photo-Tunable Multicolour Fluorescence Imaging Based on Self-Assembled Fluorogenic Nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 5326. 10.1039/c3cc48464e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonacchi S.; Cantelli A.; Battistelli G.; Guidetti G.; Calvaresi M.; Manzi J.; Gabrielli L.; Ramadori F.; Gambarin A.; Mancin F.; Montalti M. Photoswitchable NIR-Emitting Gold Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11064–11068. 10.1002/anie.201604290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampazzo E.; Bonacchi S.; Juris R.; Montalti M.; Genovese D.; Zaccheroni N.; Prodi L.; Rambaldi D. C.; Zattoni A.; Reschiglian P. Energy Transfer from Silica Core–Surfactant Shell Nanoparticles to Hosted Molecular Fluorophores. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 14605–14613. 10.1021/jp1023444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonacchi S.; Rampazzo E.; Montalti M.; Prodi L.; Zaccheroni N.; Mancin F.; Teolato P. Amplified Fluorescence Response of Chemosensors Grafted onto Silica Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2008, 24, 8387–8392. 10.1021/la800753f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.