Abstract

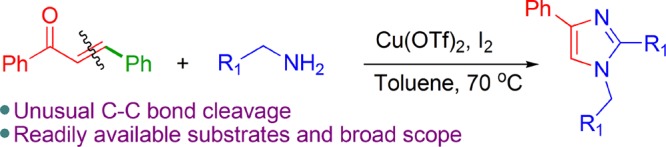

1,2,4-Trisubstituted-(1H)-imidazoles have been synthesized by the Cu(OTf)2- and I2-catalyzed unusual C–C bond cleavage of chalcones and benzylamines. After the α,β-unsaturated C–C bond cleavage, the β-portion is eliminated from the reaction. Various aryl- and heteroaryl-substituted chalcones and benzylamines were well tolerated in this unusual transformation to yield the trisubstituted-(1H)-imidazoles.

Introduction

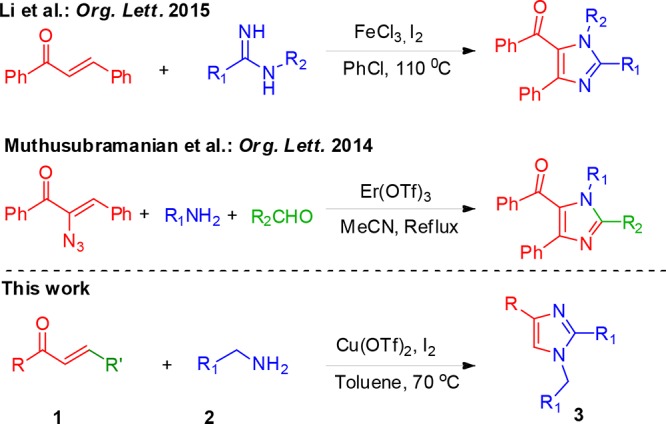

Chalcone, a naturally available α,β-unsaturated ketone,1 is well-known for its broad spectrum of medicinal values.1−7 The researchers are always curious in the structural modification and utilization of chalcones in the discovery of new active pharmaceutical ingredients.8 It may be attributed to their abundance in the natural resources and the ease at which these molecules can be synthesized.1 In many instances, quantitative structure–activity relationship studies revealed that the modified chalcones have led to the improved activity as well as the exhibition of an entirely new biological property.9 Besides, the presence of enone functionality always makes it a better precursor for an array of chemical reactions1,10 The 1,4-Michael addition of chalcones with a variety of nucleophiles is very well reported.11 Cycloaddition such as 4 + 2,12 3 + 2,13 and 4 + 1 annulations14 has been reported with the enone system in the divergent synthesis of heterocycles and highly substituted arenes.15 Alongside, the CH activation reaction16 and numerous Lewis acid catalyzed transformations have also been reported.17 In 2015, Zhu et al. demonstrated a facile FeCl3–I2-catalyzed coupling of amidines with chalcone in the successful preparation of tetrasubstituted imidazoles (Scheme 1).18

Scheme 1. Chalcone-Based Imidazole Synthesis.

In addition, the biological19,20 and material and polymeric21−24 significances of imidazole are also well studied. Because of the significant applications, several classical methods for the synthesis of imidazole are available.25 A series of metal-catalyzed26 and nonmetal-catalyzed27 multicomponent reactions have also been reported in the recent years. Accordingly, we envisaged that the development of a new and simple strategy using readily available chalcones and benzylamines, which use inexpensive catalysts for the construction of 1,2,4-trisubstituted-(1H)-imidazoles, would be a valuable contribution to a limited number of existing approaches (Scheme 1).

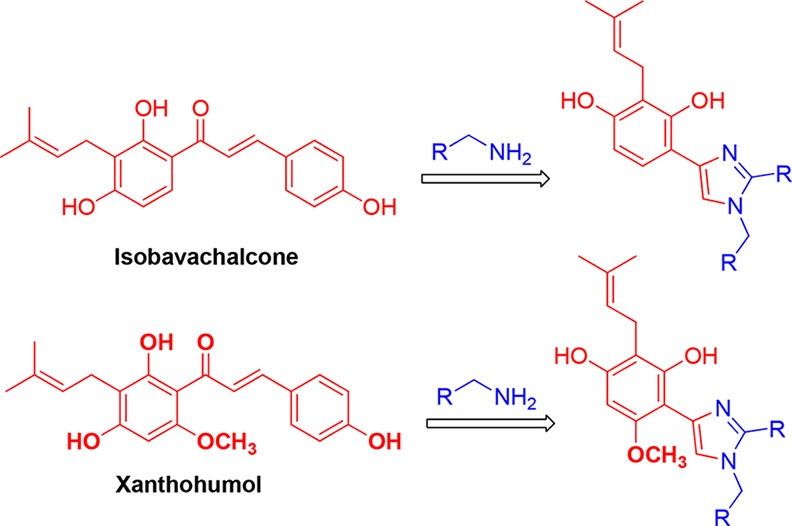

The perspective of the protocol lies in its practical utilization of medicinal chemistry approaches, viz., scaffold hopping, molecular hybridization,28 and so forth. Hit selection and lead generation are crucial to the success of lead optimization phase in drug discovery. Chalcones are considered to be one of the prioritized hits for lead generation in many therapeutic applications. Hence, the present protocol is an ideal one for the synthesis of 1,2,4-trisubstituted-(1H)-imidazole-appended hybrids from biologically relevant chalcones (Scheme 2). For instance, isobavachalcone,29 xanthohumol,30 phlorizin,31 macdentichalcone,32 cochinchinenin,33 and so forth are complex natural product chalcones, which display a broad spectrum of medicinal properties that can be adopted for this methodology to synthesize a diverse array of imidazole hybrids.

Scheme 2. Perspective of the Protocol in the Scaffold Hopping/Molecular Hybridization of Biologically Relevant Complex Natural Product-Based Chalcones to Imidazole Hybrids.

Results and Discussion

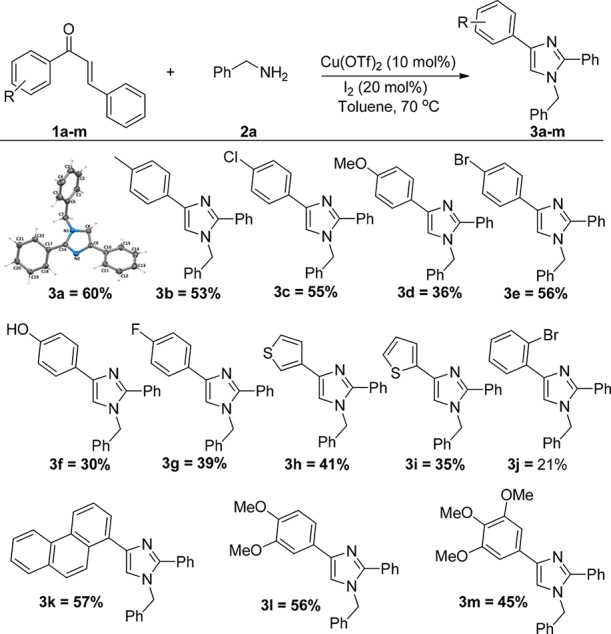

A few reports on the reactivity of copper catalyst and iodine26a,27a,34 for the synthesis of imidazoles have prompted us to examine this catalytic system. Our initial experiment was conducted between chalcone (1a, 0.24 mmol) and benzylamine (2a, 1.2 mmol) in the presence of 20 mol % of both copper acetate and iodine in dichloroethane (DCE) at 50 °C. As expected, a new product is formed and isolated after 24 h of reaction in 42% yield. Interestingly, the mass spectrometric analysis showed the high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) peak at lower mass than the expected. Further structure elucidation of NMR spectra revealed the product as 1-benzyl-2,4-diphenyl-1H-imidazole (Scheme 3). From the NMR and mass spectroscopic analysis, and the products formed from various substituted chalcones, it has been confirmed that the β-portion of the α,β-unsaturated ketone coming from aldehyde has been eliminated from the reaction, which reveals that the reaction may be going through the unusual C–C bond cleavage of chalcones. Further, the structure of the product is unambiguously confirmed from single-crystal X-ray analysis of the molecule 3a (Scheme 3, 3a). Inspired by this Cu(OAc)2- and I2-catalyzed unusual C–C bond cleavage, we started our investigation in order to optimize the process (Table 1). In the solvent optimization of polar and nonpolar solvents, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and EtOH yielded the product in trace quantity, whereas tetrahydrofuran (THF) and dimethylformamide (DMF) could not furnish the desired outcome. The reaction in acetonitrile afforded a comparatively less yield (36%). Toluene produced an improved yield of 48% in comparison with other solvents. Further, we tested the reaction using different copper(II) catalysts. Among those, CuCl2 and Cu(BF4)2 did not show any promising improvement. CuI or CuBr also failed to show the significant result. A comparatively higher yield of 52% is afforded with Cu(OTf)2 than with Cu(OAc)2. Because copper triflate is a Lewis acid, we explored the catalytic reactivity of Sc(OTf)3, Zn(OTf)3, La(OTf)3, and so forth. However, the reaction did not afford the expected product.

Scheme 3. Scope of the Reaction for Various Substituted Chalcones.

Table 1. Optimization of the Reactiona.

| solvent | catalyst | oxidant | additive | temp (°C) | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCE | Cu(OAc)2 (20 mol %) | I2 (20 mol %) | rt | trace | |

| DCE | Cu(OAc)2 | I2 | 50 | 42 | |

| THF | Cu(OAc)2 | I2 | 50 | N.R | |

| DMSO | Cu(OAc)2 | I2 | 50 | trace | |

| DMF | Cu(OAc)2 | I2 | 50 | N.R | |

| CH3CN | Cu(OAc)2 | I2 | 50 | 36 | |

| DCE | Cu(OAc)2 | 50 | N.R | ||

| DCE | I2 | 50 | N.R | ||

| DCE | I2 | H2O2 | 50 | N.R | |

| toluene | Cu(OAc)2 | I2 | 50 | 48 | |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 | I2 | 50 | 52 | |

| toluene | In(OTf)2 | I2 | 50 | trace | |

| toluene | Sc(OTf)2 | I2 | 50 | N.R | |

| toluene | CuCl2 | I2 | 50 | trace | |

| toluene | Cu(BF4)2 | I2 | 50 | 9 | |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 | I2 | BF3·OEt2 (1 equiv) | 50 | 38 |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 | I2 | BF3·OEt2 (20 mol %) | 50 | trace |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 | I2 | PTSA (20 mol %) | 50 | 20 |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 | I2 | HCl (20 mol %) | 50 | 50 |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 | I2 | 50 | 48 | |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 | PhI(OAc)2 | 50 | N.R | |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 | NaI | 50 | trace | |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 | KIO3 | 50 | N.R | |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 | CuI | 50 | 9 | |

| toluene | CuI | I2 | 50 | 21 | |

| toluene | CuBr | I2 | 50 | 26 | |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 (1 equiv) | I2 | 50 | trace | |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 (20 mol %) | I2 (1 equiv) | 50 | 31 | |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 (10 mol %) | I2 (20 mol %) | 50 | 60 | |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 (5 mol %) | I2 (5 mol %) | 50 | trace | |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2(10 mol %) | I2(20 mol %) | 60–70 | 59 | |

| toluene | Cu(OTf)2 (10 mol %) | I2 (20 mol %) | 80 | 41 | |

| tolueneb | Cu(OTf)2 (10 mol %) | I2 (20 mol %) | 60–70 | 54 | |

| toluenec | Cu(OTf)2 (10 mol %) | I2 (20 mol %) | 60–70 | 24 | |

| toluened | Cu(OTf)2 (10 mol %) | I2 (20 mol %) | 60–70 | 25 |

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.24 mmol), 2a (1.2 mmol), in 2 mL of solvent without inert atmosphere, for 24 h.

Reaction time: 14 h.

In the presence of argon atmosphere.

1a (0.24 mmol), 2a (0.72 mmol).

Different oxidants, viz., TBHP, I2, PhIOAc2, H2O2, and O2, were also added as an additive to improve the yields further. Except for I2, none of the other additives produced the desired product. Hence, Cu(OTf)2 and I2 together have been used as the catalyst for the reaction. A decrease in the loading of Cu(OTf)2 to 10 mol % at 50 °C increased the yield to 60%. Hence, 10 mol % Cu(OTf)2 and 20 mol % I2 are together considered as the catalytic system for the reaction. When 50 and 100 mol % of iodine are used, the yield has been suppressed to 38 and 31%, respectively. When the temperature of the reaction increased to 70 °C from 50 °C, the reaction proceeded comparatively clean without much change in the yield. Hence, 70 °C has been considered as the optimized temperature for the reaction. When we carried out the reaction in the presence of argon atmosphere, the reaction did not produce the expected product in the desired yield. The other parameters considered for the optimization are tabulated in Table 1.

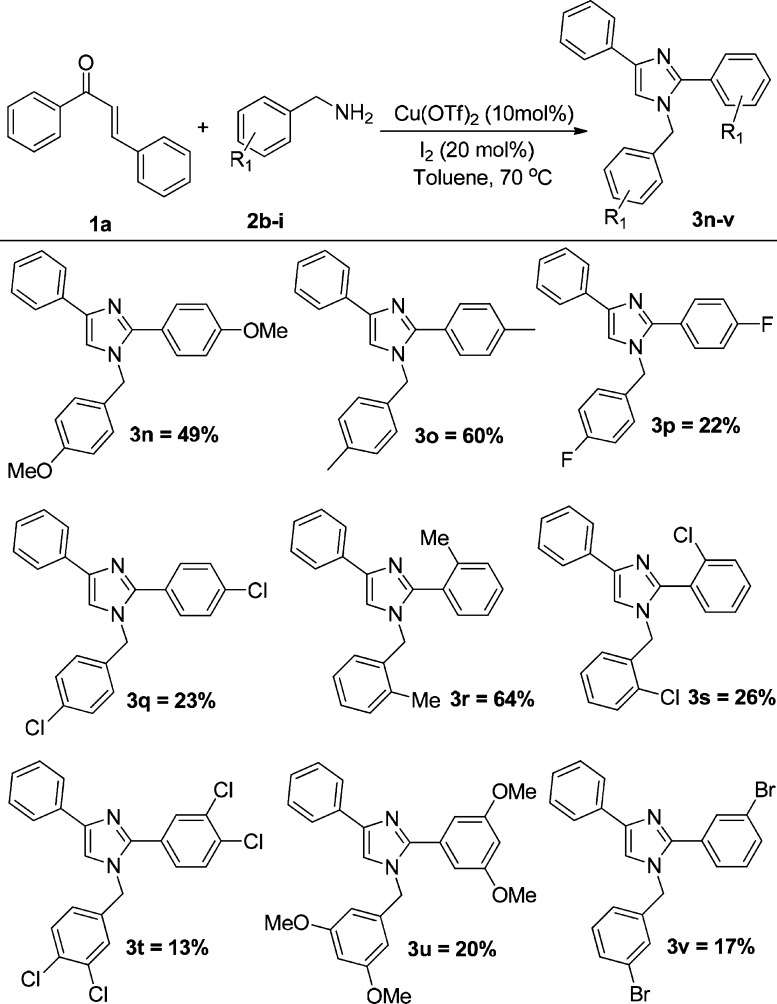

The generality of the reaction is investigated by the reaction of various substituted chalcones with substituted benzylamines under the optimized condition (Scheme 3). The reaction proceeds smoothly for all the electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substitutions on chalcone. The reaction is also generalized for 2-thiophene, 3-thiophene chalcones, and phenanthrene chalcones, which gave satisfactory yields. Therefore, for all the various substituents of chalcones with benzylamine, good-to-moderate yields have been obtained without the significant impact of the substitution (Scheme 3). However, comparatively higher yields have been received for the benzylamines with electron-donating groups than that with electron-withdrawing groups. The results are summarized in Scheme 4.

Scheme 4. Scope of the Reaction for Substituted Benzylamines.

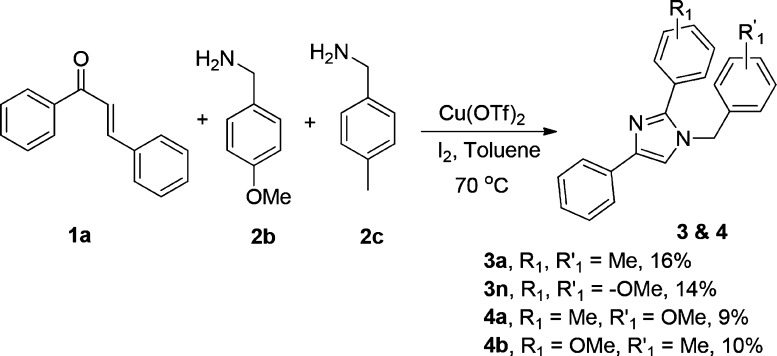

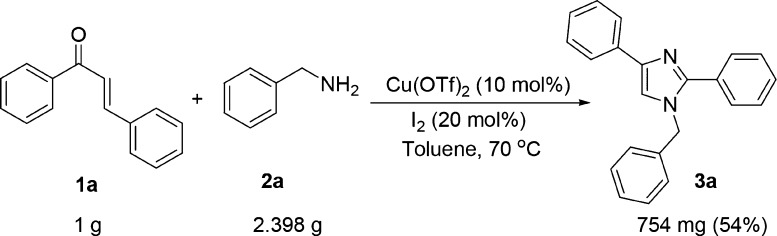

Because 2 mol of benzylamine is taking part in the reaction, we emphasized the idea of utilizing the two differently substituted benzylamines in a one-pot reaction. To our delight, the one-pot reaction through the monitored sequential addition of chalcone, (4-methoxyphenyl) methenamine, and p-tolylmethanamine gave four various substituted products as shown in Scheme 5. Hence, the protocol provides an opportunity to synthesize the library of highly substituted imidazoles in a controlled one-pot manner. Toward the demonstration of scale-up synthesis of imidazoles from chalcones and benzylamines under the optimized reaction condition was performed with 1 g of chalcone and 2.39 g of benzylamine. We have successfully obtained the corresponding imidazole in 54% yield (754 mg) (Scheme 6). This shows that the protocol is well optimized even for carrying out the gram-scale synthesis of imidazole derivatives for various applications.

Scheme 5. Imidazole Synthesis with Two Different Substituted Benzylamines.

Scheme 6. Gram-Scale Synthesis of Imidazole from (E)-Chalcone and Benzylamine.

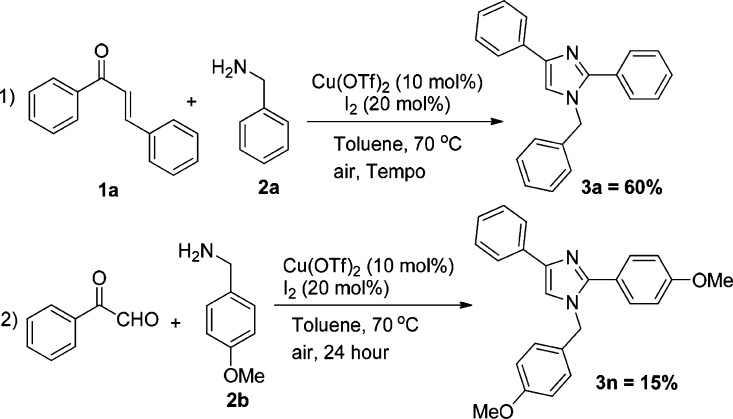

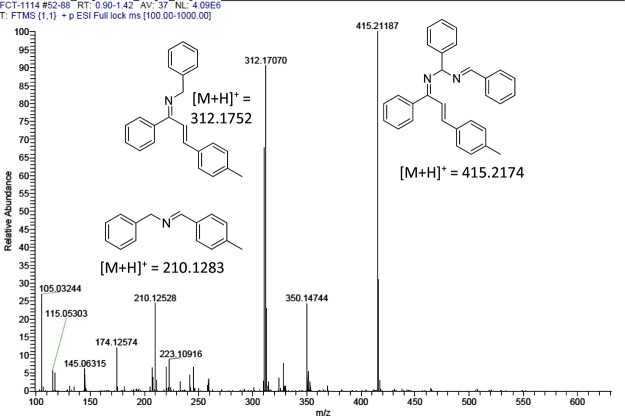

To gain some insights into this unusual C–C bond cleavage of chalcones leading to the imidazole formation, we have carried out some controlled experiments. The yield did not decrease when a radical scavenger (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxidanyl (TEMPO) was added to the reaction; thus, a radical process is probably unlikely to be involved (Scheme 7, exp 1). Anticipating a cleavage of chalcone, subsequent transformation to phenylglyoxal, and its involvement in the product formation, we conducted an experiment with phenylglyoxal and 4-methoxy-benzylamine under the optimized reaction condition. However, the reaction afforded the desired product in very less amount even after 24 h, which indicates that the reaction is not going through phenylglyoxal (Scheme 7, exp 2) as the intermediate. Further, we have conducted three experiments with 1 equiv, 2 equiv, and 4 equiv of benzylamines, respectively. The HRMS of each reaction was analyzed at different time intervals to identify the intermediates formed. According to the controlled experiments and the HRMS analysis of a reaction mixture with 1 equiv of benzylamine (after 1 h) (Figures 1, S1, and S4, Supporting Information), we have proposed a plausible mechanism (Scheme 8).

Scheme 7. Controlled Experiments.

Figure 1.

HRMS for the reaction mixture of 1 equiv of benzylamine and chalcone after 1 h of the reaction time.

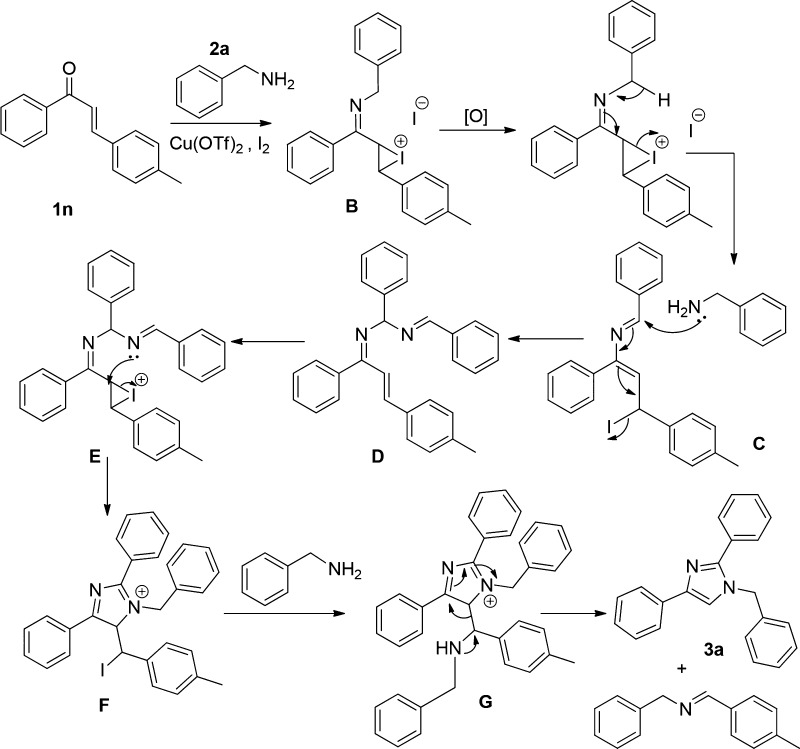

Scheme 8. Plausible Mechanism of the Reaction.

In the presence of copper triflate, benzylamine reacts with chalcone to form the corresponding imine [(M + H)+ = 312.1704], followed by the reaction of iodine to the corresponding imine to form an iodonium ion intermediate B. Addition of amine to imine, followed by rearrangement, leads to the intermediate C, which on air oxidation gives D [(M + H)+ = 415.2115]. Further, iodonium ion formation and intramolecular cyclization of E provide the intermediate F. Nucleophilic substitution on F from benzylamine gives the intermediate G. Finally, imine formation and subsequent C–C bond cleavage of G lead to an aromatized product of 1,2,4-trisubstituted-(1H)-imidazoles.

Conclusions

In summary, a new and simple route for the synthesis of 1,2,4-trisubstituted-(1H)-imidazoles via Cu(OTf)2-/I2-catalyzed unusual C–C bond cleavage of chalcones and benzylamines is developed. The reaction tolerates a wide range of functional groups to produce the products in good-to-moderate yields. The plausible mechanism of this unusual C–C bond cleavage and imidazole formation was hypothesized through controlled experiments and HRMS analysis. Hence, the methodology can be utilized in medicinal chemistry approaches, such as scaffold hopping, molecular hybridization, and so forth for the selective synthesis of imidazole-appended hybrids from bioactive chalcones.

Experimental Section

General Methods

All the reactions were performed with commercially available best grade chemicals without further purification. All the solvents used were of reagent grade, column chromatography was performed using 100–200 mesh silica gel, and mixtures of hexane–ethyl acetate were used for elution of the products. Melting points were determined on a Büchi melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. The proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AMX 500 spectrophotometer (CDCl3 as the solvent). The chemical shifts for 1H NMR spectra are reported as δ in units of parts per million (ppm) downfield from SiMe4 (δ 0.0) and relative to the signal of chloroform-d (δ 7.25, singlet). Multiplicities were given as s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), dd (double doublet), and m (multiplet). The coupling constants are reported as J value in hertz. The carbon NMR (13C NMR) spectra are reported as δ in units of ppm downfield from SiMe4 (δ 0.0) and relative to the signal of chloroform-d (δ 77.03, triplet). The mass spectra were recorded under EI/HRMS at 60,000 resolution using a Thermo Scientific Exactive mass spectrometer. The IR spectra were recorded on a Bruker FT-IR spectrometer. All the substituted chalcones were synthesized using literature reports.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of (E)-Chalcone35

One equivalent of arylaldehyde or heteroarylaldehyde was added to the solution of 1 equiv of acetophenone in ethanol. The 10% aqueous solution of NaOH was added dropwise to the mixture at 0 °C, which resulted in precipitation. The mixture was then stirred for 30 min, filtered, washed with cold methanol, and dried to yield 60–90% solid compound. The product was confirmed from 1H NMR.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Imidazole

Copper triflate (10 mol %) and 20 mol % of iodine were added to the mixture of 1 equiv of chalcone (0.24 mmol, 50 mg) and 5 equiv of benzylamine (1.2 mmol, 128.58 mg), respectively, in a Schlenk tube fitted with a rubber septum. Toluene (2 mL) was added to it and stirred at 70 °C for 24 h in the presence of air. The reaction mixture was cooled and extracted with EtOAc–water mixture, by addition of sodium thiosulfate. The organic layer was separated and evaporated in vacuo. The product was separated with a silica gel (100–200 mesh) column chromatography using the mixture of 10–18% EtOAc in hexane.

General Procedure for the Controlled Experiments

Reaction with TEMPO-Free Radical

Copper triflate (10 mol %), 20 mol % of iodine, and one equivalent of TEMPO-free radical were added to the mixture of 1 equiv of chalcone (0.24 mmol, 50 mg) and 5 equiv of benzylamine (1.2 mmol, 128.58 mg) in a Schlenk tube fitted with a rubber septum. Toluene (2 mL) was added to it and stirred at 70 °C for 24 h in the presence of air. The reaction mixture was cooled and extracted with EtOAc–water mixture, by addition of sodium thiosulfate. The organic layer was separated and evaporated in vacuo. The product was separated with a silica gel (100–200 mesh) column chromatography using the mixture of 10–18% EtOAc in hexane.

Reaction of Phenylglyoxal with 4-Methoxy Benzylamine

Copper triflate (10 mol %) and 20 mol % of iodine were added to the mixture of 1 equiv of phenylglyoxal (0.34 mmol, 50 mg) and 3 equiv of 4-methoxybenzylamine (1.2 mmol, 123.67 mg) in a Schlenk tube fitted with a rubber septum. Toluene (2 mL) was added to it and stirred at 70 °C for 24 h in the presence of air. The reaction mixture was cooled and extracted with EtOAc–water mixture, by addition of sodium thiosulfate. The organic layer was separated and evaporated in vacuo. The product was separated with a silica gel (100–200 mesh) column chromatography using the mixture of 10–18% EtOAc in hexane.

Characterization of the Products

1-Benzyl-2,4-diphenyl-1H-imidazole (3a)

Yield: 45 mg, 60% yield, as a light orange solid; Rf = 0.36 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80/20); mp 110–112 °C; IR (neat, cm–1): 3062, 2929, 1955, 1888, 1673, 1452, 1357, 1276, 1082, 1027; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.21 (s, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.22–7.25 (m, 2H), 7.31–7.38 (m, 5H), 7.41–7.43 (m, 3H), 7.59–7.62 (m, 2H), 7.83 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.5, 116.9, 124.9, 126.7, 126.9, 128.0, 128.3, 128.6, 128.7, 129.1, 129.1, 130.5, 136.7, 141.6, 148.7; HRMS: calcd for C22H19N2 ([M + H]+), 311.1548; found, 311.1555.

1-Benzyl-2-phenyl-4-(p-tolyl)-1H-imidazole (3b)

Yield: 41 mg, 53% yield as a light yellow solid; Rf = 0.34 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80/20); mp 132–134 °C; IR (neat, cm–1): 3030, 2921, 2885, 1662, 1608, 1532, 1459, 1371, 1269, 1113, 1037, 821; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.34 (s, 3H), 5.19 (s, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 7.28–7.35 (m, 3H), 7.38–7.42 (m, 3H), 7.58–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 21.3, 50.5, 116.4, 124.9, 126.7, 127.9, 128.7, 128.9, 129.0, 129.1, 129.3, 130.5, 131.3, 136.5, 136.9, 141.7, 148.5; HRMS: calcd for C23H21N2 ([M + H]+), 325.1705; found, 325.1707.

1-Benzyl-4-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3c)

Yield: 46 mg, 55% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.32 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80/20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3030, 2859, 1957, 1809, 1666, 1577, 1452, 1274, 1082, 1027; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.19 (s, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (s, 1H), 7.31–7.37 (m, 5H), 7.41–7.42 (m, 3H), 7.58–7.60 (m, 2H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.6, 116.9, 126.2, 126.7, 128.1, 128.7, 128.7, 129.0, 129.1, 129.2, 130.3, 132.3, 132.6, 136.7, 140.5, 148.8; HRMS: C22H18ClN2 ([M + H]+), 345.1159; found, 345.1148.

1-Benzyl-4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3d)

Yield: 29 mg, 36% yield as a light yellow solid; Rf = 0.24 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80/20); mp 86–88 °C; IR (neat, cm–1): 3063, 3002, 2047, 1891, 1659, 1564, 1451, 1247, 1175; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.83 (s, 3H), 5.22 (s, 2H), 6.91 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (s, 1H), 7.31–737 (m, 3H), 7.41–7.42 (m, 3H), 7.59–7.62 (m, 2H), 7.76 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.5, 55.3, 113.9, 115.8, 126.2, 126.7, 126.9, 127.9, 128.7, 128.9, 129.0, 129.0, 130.5, 136.9, 141.4, 148.4, 158.7; HRMS: calcd for C23H21N2O ([M + H]+), 341.1654; found, 341.1637.

1-Benzyl-4-(4-bromophenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3e)

Yield: 52 mg, 56% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.36 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80/20); mp 142–144 °C; IR (neat, cm–1): 3062, 2924, 1955, 1900, 1662, 1476, 1359, 1267, 1072, 833; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.22 (s, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.24 (s, 1H), 7.32–7.38 (m, 3H), 7.41–7.44 (m, 3H), 7.48 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.59–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.6, 117.0, 120.5, 126.5, 126.8, 128.1, 128.7, 129.0, 129.1, 129.2, 130.3, 131.6, 133.1, 136.7, 140.5, 148.9; HRMS: calcd for C22H18BrN2 ([M + H]+), 389.0653; found, 389.0635.

4-(1-Benzyl-2-phenyl-1H-imidazole-4-yl)phenol (3f)

Yield: 24 mg, 30% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.11 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80/20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3292, 3032, 2804, 1955, 1806, 1604, 1451, 1359, 1270, 1168; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.17 (s, 2H), 6.71 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.08 (s, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.30–7.38 (m, 7H), 7.54–7.55 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.5, 115.7, 115.8, 125.2, 126.5, 126.7, 128.1, 128.7, 129.1, 129.2, 129.7, 136.7, 141.6, 148.4, 156.1; HRMS: calcd C22H19N2O ([M + H]+), 327.1497; found, 327.1488.

1-Benzyl-4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3g)

Yield: 31 mg, 39% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.29 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80/20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3065, 2930, 1667, 1599, 1497, 1332, 1222, 1155, 841, 732; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.22 (s, 2H), 7.05 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 7.30–7.37 (m, 3H), 7.42–7.44 (m, 3H), 7.59–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.78–7.80 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.5, 115.3, 115.5, 116.4, 126.5, 126.6, 126.7, 128.1, 128.7, 129.0, 129.1, 130.3, 130.3, 136.8, 140.7, 148.7, 162.0 (d, J = 243.75 Hz); HRMS: calcd for C22H18FN2 ([M + H]+), 329.1454; found, 329.1441.

1-Benzyl-2-phenyl-4-(thiophen-3-yl)-1H-imidazole (3h)

Yield: 31 mg, 41% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.29 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80/20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3106, 2928, 1662, 1604, 1498, 1351, 1250, 1169, 1024, 884; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.19 (s, 2H), 7.11–7.13 (m, 3H), 7.29–7.35 (m, 4H), 7.38 (dd, J = 5.0 Hz, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.39–7.42 (m, 3H), 7.58–7.59 (m, 2H), 7.64 (dd, J = 3.0 Hz, 1.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.4, 116.7, 119.2, 125.6, 125.8, 126.7, 128.0, 129.0, 129.1, 130.3, 135.8, 136.9, 138.1, 148.5; HRMS: calcd for C20H17N2S ([M + H]+), 317.1112; found, 317.1113.

1-Benzyl-2-phenyl-4-(thiophen-2-yl)-1H-imidazole (3i)

Yield: 27 mg, 35% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.29 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80/20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3064, 2929, 1652, 1618, 1498, 1359, 1181, 1027, 846, 768; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.19 (s, 2H), 7.02 (dd, J = 5.0 Hz, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 7.12–7.15 (m, 3H), 7.18 (dd, J = 5.0 Hz, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.31–7.37 (m, 4H), 7.40–7.42 (m, 3H), 7.58–7.59 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.5, 116.3, 122.1, 123.3, 126.7, 127.5, 128.1, 128.4, 128.7, 129.0, 129.1, 129.1, 129.2, 130.1, 136.7, 136.8, 137.8, 143.4, 148.5; HRMS: calcd for C20H17N2S ([M + H]+), 317.1112; found, 317.1108.

1-Benzyl-4-(2-bromophenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3j)

Yield: 20 mg, 21% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.45 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3062, 2927, 1661, 1595, 1472, 1358, 1262, 1183, 1023, 745; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.28 (s, 2H), 7.09 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 7.41–7.42 (m, 3H), 7.59–7.62 (m, 3H), 7.79 (s, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.6, 120.7, 121.3, 126.6, 127.5, 127.9, 127.9, 128.7, 129.0, 129.1, 130.3, 130.5, 133.5, 134.5, 136.8, 138.8, 147.7; HRMS: calcd for C22H18BrN2 ([M + H]+), 389.0653; found, 389.0663.

1-Benzyl-4-(phenanthren-1-yl)-2-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3k)

Yield: 56 mg, 57% yield as a white viscous solid; Rf = 0.31 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3032, 2853, 1672, 1603, 1493, 1359, 1240, 1177, 1077, 892; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.27 (s, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.34–7.39 (m, 3H), 7.42 (s, 1H), 7.45–7.46 (m, 3H), 7.55–7.58 (m, 1H), 7.62–7.67 (m, 3H), 7.72 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (dd, J = 7.5 Hz, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 8.07 (dd, J = 8.5 Hz, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.67 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.6, 117.4, 122.6, 122.9, 123.9, 124.1, 126.3, 126.5, 126.8, 127.1, 127.3, 128.1, 128.6, 128.7, 129.1, 129.1, 129.1, 129.2, 130.4, 131.9, 132.3, 132.5, 136.8, 141.3, 148.9; HRMS: calcd for C30H23N2 ([M + H]+), 411.1861; found, 411.1801.

1-Benzyl-4-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3l)

Yield: 50 mg, 56% yield as a light yellow solid; Rf = 0.10 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); mp 105–107 °C; IR (neat, cm–1): 3031, 2935, 1666, 1586, 1457, 1342, 1252, 1165, 1026, 862; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.96 (s, 3H), 5.22 (s, 2H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 7.31–7.38 (m, 4H), 7.41–7.45 (m, 4H), 7.61–7.62 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.5, 55.9, 56.0, 108.4, 111.3, 116.1, 117.2, 126.7, 127.4, 127.9, 128.7, 129.0, 129.1, 130.5, 136.9, 141.5, 148.1, 148.5, 149.1; HRMS: calcd for C24H23N2O2 ([M + H]+), 371.1760; found, 371.1710.

1-Benzyl-2-phenyl-4-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-1H-imidazole (3m)

Yield: 43 mg, 45% yield as a light yellow solid; Rf = 0.08 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); mp 135–137 °C; IR (neat, cm–1): 3030, 2834, 1671, 1586, 1497, 1340, 1232, 1184, 1006, 853; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.92 (s, 6H), 5.23 (s, 2H), 7.07 (s, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (s, 1H), 7.32–7.39 (m, 3H), 7.41–7.44 (m, 3H), 7.61–7.63 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.5, 56.2, 60.9, 102.1, 116.6, 126.6, 128.0, 128.7, 129.1, 129.1, 129.9, 130.4, 136.9, 137.2, 141.5, 148.6, 153.5; HRMS: calcd for C25H25N2O3 ([M + H]+), 401.1865; found, 401.1807.

1-(4-Methoxybenzyl)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3n)

Yield: 44 mg, 49% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.22 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3003, 2844, 1955, 1881, 1610, 1514, 1457, 1252, 1177, 1029; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 5.12 (s, 2H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.20–7.24 (m, 2H), 7.35 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.55 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.0, 55.3, 55.4, 114.1, 114.4, 116.4, 123.0, 124.9, 126.7, 128.1, 128.5, 128.9, 130.5, 134.2, 141.2, 148.5, 159.3, 160.2; HRMS: calcd for C24H22N2O2 [M + H]+, 371.1760; found, 371.1749.

1-(4-Methylbenzyl)-4-phenyl-2-(p-tolyl)-1H-imidazole (3o)

Yield: 49 mg, 60% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.45 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); mp 85–87 °C; IR (neat, cm–1): 3028, 2732, 1948, 1804, 1664, 1515, 1483, 1417, 1310, 1182; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.35 (s, 3H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 5.16 (s, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.22–7.24 (m, 4H), 7.35 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 21.1, 21.4, 50.3, 116.7, 124.9, 126.7, 128.5, 128.9, 129.3, 129.7, 133.9, 134.2, 137.8, 138.9, 141.3, 148.7; HRMS: calcd for C24H23N2 ([M + H]+), 339.1861; found, 339.1867.

1-(4-Fluorobenzyl)-2-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3p)

Yield: 19 mg, 22% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.43 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3129, 2929, 2049, 1952, 1816, 1671, 1482, 1391, 1159, 732; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.16 (s, 2H), 7.02–7.14 (m, 6H), 7.24–7.26 (m, 2H), 7.37 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.54–7.57 (m, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR: (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 49.9, 115.7, 115.9, 116.0, 116.2, 116.7, 124.9, 126.5, 126.6, 127.0, 128.4, 128.6, 130.9, 130.9, 132.4, 133.8, 141.7, 147.6, 147.6, 162.4 (d, J = 246.25), 163.24 (d, J = 247.50); HRMS: calcd for C22H17F2N2 ([M + H]+), 347.1360; found, 347.1342.

1-(4-Chlorobenzyl)-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3q)

Yield: 21 mg, 23% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.50 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); IR (neat, cm–1): 2927, 2854, 1901, 1648, 1489, 1412, 1179, 1013, 834, 732; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.17 (s, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.24–7.27 (m, 2H), 7.33 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.36–7.41 (m, 4H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR: (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 49.9, 117.0, 124.9, 127.1, 127.9, 128.7, 128.7, 128.9, 129.3, 130.2, 133.7, 134.1, 135.1, 135.3, 141.9, 147.4; HRMS: calcd for C22H17Cl2N2 [M + H]+, 379.0769; found, 379.0763.

1-(2-Methylbenzyl)-4-phenyl-2-(o-tolyl)-1H-imidazole (3r)

Yield: 52 mg, 64% yield as an amorphous foam; Rf = 0.42 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); mp 82–84 °C; IR (neat, cm–1): 3061, 2925, 1668, 1606, 1482, 1351, 1194, 1083, 1027, 869; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.27 (s, 3H), 4.91 (s, 2H), 6.97 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.12–7.17 (m, 3H), 7.21 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 7.28–7.35 (m, 5H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 18.9, 19.9, 48.4, 115.2, 124.8, 125.7, 126.5, 126.7, 127.9, 128.2, 128.6, 129.5, 130.2, 130.4, 130.5, 130.6, 134.3, 134.5, 135.8, 138.7, 140.9, 148.1; HRMS: calcd for C24H23N2 ([M + H]+), 339.1861; found, 339.1867.

1-(2-Chlorobenzyl)-2-(2-chlorophenyl)-4-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3s)

Yield: 24 mg, 26% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.27 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3062, 2930, 1657, 1605, 1444, 1376, 1277, 1183, 1088, 753; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.11 (s, 2H), 6.93 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.17–7.26 (m, 3H), 7.30–7.42 (m, 6H), 7.47–7.49 (m, 2H), 7.81 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 48.2, 115.8, 124.9, 126.9, 127.0, 127.0, 127.3, 128.6, 128.6, 129.3, 129.5, 129.7, 130.0, 131.1, 132.8, 133.1, 133.8, 133.9, 134.8, 141.6, 145.9; HRMS: calcd for C22H17Cl2N2 ([M + H]+), 379.0769; found, 379.0764.

1-(3,5-Dichlorobenzyl)-2-(3,5-dichlorophenyl)-4-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3t)

Yield: 14 mg, 13% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.27 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3064, 2856, 1665, 1598, 1470, 1276, 1178, 1031, 822, 754; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.18 (s, 2H), 6.94 (dd, J = 8.0 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.35–7.41 (m, 4H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.73 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 49.6, 117.3, 125.0, 125.8, 127.4, 127.7, 128.6, 128.7, 129.9, 130.7, 130.8, 131.3, 132.7, 133.2, 133.4, 133.6, 133.6, 136.4, 142.4, 146.1. HRMS: calcd for C22H15Cl4N2 ([(M + 2) + H]+), 448.9960; found, 448.9962.

1-(3,5-Dimethoxybenzyl)-2-(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-4-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3u)

Yield: 21 mg, 20% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.12 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3001, 2840, 1667, 1600, 1428, 1346, 1204, 1156, 1064, 840; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.74 (s, 6H), 3.75 (s, 6H), 5.17 (s, 2H), 6.29 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H), 6.38 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.51 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H), 7.24 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.84 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.6, 55.4, 55.4, 99.6, 101.8, 104.8, 106.9, 117.1, 124.9, 126.9, 128.6, 132.0, 133.9, 139.3, 141.4, 148.4, 160.8, 161.4; HRMS: calcd for C26H27N2O4 ([M + H]+), 431.1971; found, 431.1985.

1-(3-Bromobenzyl)-2-(3-bromophenyl)-4-phenyl-1H-imidazole (3v)

Yield: 19 mg, 17% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.43 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3061, 2928, 1666, 1597, 1471, 1277, 1177, 1039, 889, 693; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.18 (s, 2H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.26–7.30 (m, 3H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 7.46 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 50.0, 117.2, 122.8, 123.2, 125.0, 125.3, 127.2, 127.3, 128.6, 129.8, 130.2, 130.7, 131.4, 132.1, 132.2, 133.7, 138.7, 142.1, 146.9; HRMS: calcd for C22H17Br2N2 ([(M + 2) + H]+), 468.9738; found, 468.9724.

1-(4-Methoxybenzyl)-4-phenyl-2-(p-tolyl)-1H-imidazole (4a)

Yield: 8 mg, 9% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.25 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3027, 2846, 1664, 1514, 1457, 1308, 1252, 1176, 1029, 887, 693; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.93 (s, 3H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 5.14 (s, 2H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.21–7.25 (m, 4H), 7.35 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.81 (dd, J = 8.5 Hz, 1.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 21.4, 50.0, 55.3, 114.4, 116.5, 124.9, 126.7, 127.7, 128.2, 128.5, 128.9, 129.3, 134.2, 138.9, 141.3, 148.7, 159.3; HRMS: calcd for C24H23N2O ([M + H]+), 355.1810; found, 355.1809.

2-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-1-(4-methylbenzyl)-4-phenyl-1H-imidazole (4b)

Yield: 9 mg, 10% yield as an amorphous solid; Rf = 0.24 (hexane/ethyl acetate = 80:20); IR (neat, cm–1): 3061, 2928, 1612, 1597, 1482, 1417, 1277, 1181, 1039, 868, 693; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.35 (s, 3H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 5.15 (s, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.21–7.22 (m, 2H), 7.36 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 21.1, 50.3, 55.4, 114.1, 116.5, 122.9, 124.9, 126.7, 128.5, 129.7, 130.4, 133.9, 134.2, 137.8, 141.2, 148.5, 160.2; HRMS: calcd for C24H23N2O ([M + H]+), 355.1810; found, 355.1811.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the DST-Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), Government of India, New Delhi, India (grant no. EEQ/2016/000089) is gratefully acknowledged. C.T.F.S. thanks the UGC for research fellowship.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b01017.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Zhuang C.; Zhang W.; Sheng C.; Zhang W.; Xing C.; Miao Z. Chalcone: A Privileged Structure in Medicinal Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 7762–7810. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boumendjel A.; Boccard J.; Carrupt P.-A.; Nicolle E.; Blanc M.; Geze A.; Choisnard L.; Wouessidjewe D.; Matera E.-L.; Dumontet C. Antimitotic and antiproliferative activities of chalcones: forward structure–activity relationship. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 2307–2310. 10.1021/jm0708331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P.; Anand A.; Kumar V. Recent developments in biological activities of chalcones: a mini review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 85, 758–777. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S. F.; Boesen T.; Larsen M.; Schønning K.; Kromann H. Antibacterial chalcones––bioisosteric replacement of the 4′-hydroxy group. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 3047–3054. 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Nowakowska Z. A review of anti-infective and anti-inflammatory chalcones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 42, 125–137. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Won S.-J.; Liu C.-T.; Tsao L.-T.; Weng J.-R.; Ko H.-H.; Wang J.-P.; Lin C.-N. Synthetic chalcones as potential anti-inflammatory and cancer chemopreventive agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 40, 103–112. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anto R. J.; Sukumaran K.; Kuttan G.; Rao M. N. A.; Subbaraju V.; Kuttan R. Anticancer and antioxidant activity of synthetic chalcones and related compounds. Cancer Lett. 1995, 97, 33–37. 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03945-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorova I.; Batovska D.; Stamboliyska B.; Parushev S. Evaluation of the radical scavenging activity of a series of synthetic hydroxychalcones towards the DPPH radical. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2011, 76, 491–497. 10.2298/jsc100517043t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Gomes M.; Muratov E.; Pereira M.; Peixoto J.; Rosseto L.; Cravo P.; Andrade C.; Neves B. Chalcone Derivatives: Promising Starting Points for Drug Design. Molecules 2017, 22, 1210–1235. 10.3390/molecules22081210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Priyadarshani G.; Nayak A.; Amrutkar S. M.; Das S.; Guchhait S. K.; Kundu C. N.; Banerjee U. C. Scaffold-Hopping of Aurones: 2-Arylideneimidazo[1,2-a]pyridinones as Topoisomerase IIα-Inhibiting Anticancer Agents. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 1056–1061. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Rosa G. P.; Seca A. M. L.; Barreto M. d. C.; Pinto D. C. G. A. Chalcone: A Valuable Scaffold Upgrading by Green Methods. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 7467–7480. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b01687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Sivakumar P. M.; Seenivasan S. P.; Kumar V.; Doble M. Synthesis, antimycobacterial activity evaluation, and QSAR studies of chalcone derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 1695–1700. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Qiao Z.; Wang Q.; Zhang F.; Wang Z.; Bowling T.; Nare B.; Jacobs R. T.; Zhang J.; Ding D.; Liu Y.; Zhou H. Chalcone–benzoxaborole hybrid molecules as potent antitrypanosomal agents. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3553–3557. 10.1021/jm2012408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque H.; Santos C.; Cavaleiro J.; Silva A. Chalcones as Versatile Synthons for the Synthesis of 5- and 6-membered Nitrogen Heterocycles. Curr. Org. Chem. 2014, 18, 2750–2775. 10.2174/1385272819666141013224253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhan Z.-P.; Yang R.-F.; Lang K. Samarium triiodide-catalyzed conjugate addition of indoles with electron-deficient olefins. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 3859–3862. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.03.174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Manzano R.; Andrés J. M.; Álvarez R.; Muruzábal M. D.; de Lera Á. R.; Pedrosa R. Enantioselective Conjugate Addition of Nitro Compounds to α,β-Unsaturated Ketones: An Experimental and Computational Study. Chem.—Eur. J. 2011, 17, 5931–5938. 10.1002/chem.201100241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Opekar S.; Pohl R.; Eigner V.; Beier P. Conjugate Addition of Diethyl 1-Fluoro-1-phenylsulfonylmethanephosphonate to α,β-Unsaturated Compounds. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 4573–4579. 10.1021/jo400297f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Patonay T.; Varma R. S.; Vass A.; Lévai A.; Dudás J. Highly diastereoselective Michael reaction under solvent-free conditions using microwaves: conjugate addition of flavanone to its chalcone precursor. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 1403–1406. 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)02264-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Ooi T.; Ohara D.; Fukumoto K.; Maruoka K. Importance of Chiral Phase-Transfer Catalysts with Dual Functions in Obtaining High Enantioselectivity in the Michael Reaction of Malonates and Chalcone Derivatives. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 3195–3197. 10.1021/ol050902a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Yang W.; Du D.-M. Highly Enantioselective Michael Addition of Nitroalkanes to Chalcones Using Chiral Squaramides as Hydrogen Bonding Organocatalysts. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5450–5453. 10.1021/ol102294g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yang G.; Chen L.; Wang J.; Jia Q.; Wei J.; Du Z. Facile synthesis of pyrimidines via iminium catalyzed [4+2] reaction of α,β-unsaturated ketones with 1,3,5-triazines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 5889–5891. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.09.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Cui H.-L.; Tanaka F. Catalytic Enantioselective Formal Hetero-Diels-Alder Reactions of Enones with Isatins to Give Spirooxindole Tetrahydropyranones. Chem.—Eur. J. 2013, 19, 6213–6216. 10.1002/chem.201300595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Li H.; Wang Z.; Zu L. [3 + 2] Annulations between indoles and α,β-unsaturated ketones: access to pyrrolo[1,2-a]indoles and model reactions toward the originally assigned structure of yuremamine. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 60962–60965. 10.1039/c5ra11904a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Bai X.-F.; Xu Z.; Xia C.-G.; Zheng Z.-J.; Xu L.-W. Aromatic-Amide-Derived Nonbiaryl Atropisomer as Highly Efficient Ligand for Asymmetric Silver-Catalyzed [3 + 2] Cycloaddition. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 6016–6020. 10.1021/acscatal.5b01685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chagarovsky A. O.; Budynina E. M.; Ivanova O. A.; Villemson E. V.; Rybakov V. B.; Trushkov I. V.; Melnikov M. Y. Reaction of Corey ylide with α,β-unsaturated ketones: tuning of chemoselectivity toward dihydrofuran synthesis. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 2830–2833. 10.1021/ol500877c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi P. R.; Undeela S.; Reddy D. D.; Singarapu K. K.; Menon R. S. Regioselective Synthesis of Substituted Arenes via Aerobic Oxidative [3 + 3] Benzannulation Reactions of α,β-Unsaturated Aldehydes and Ketones. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1449–1452. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z.; Grohmann C.; Glorius F. Mild Rhodium(III)-Catalyzed Cyclization of Amides with α,β-Unsaturated Aldehydes and Ketones to Azepinones: Application to the Synthesis of the Homoprotoberberine Framework. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 5393–5397. 10.1002/anie.201301426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Huang X.; Yang Y. Acylation of Alkylidenecyclopropanes for the Facile Synthesis of α,β-Unsaturated Ketone and Benzofulvene Derivatives with High Stereoselectivity. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1667–1670. 10.1021/ol070331h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Grisin A.; Oliver S.; Ganton M. D.; Bacsa J.; Evans P. A. Diastereoselective construction of anti-4,5-disubstituted-1,3-dioxolanes via a bismuth-mediated two-component hemiacetal oxa-conjugate addition of γ-hydroxy-α,β-unsaturated ketones with paraformaldehyde. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 15681–15684. 10.1039/c5cc01949d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.; Li C.; Zhang J.; She M.; Sun W.; Wan K.; Wang Y.; Yin B.; Liu P.; Li J. A Facile FeCl3/I2-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidative Coupling Reaction: Synthesis of Tetrasubstituted Imidazoles from Amidines and Chalcones. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 3872–3875. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Narasimhan B.; Sharma D.; Kumar P. Biological importance of imidazole nucleus in the new millennium. Med. Chem. Res. 2011, 20, 1119–1140. 10.1007/s00044-010-9472-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Shalini K.; Sharma P.; Kumar N. Imidazole and its biological activities: A review. Chem. Sin. 2010, 1, 36–47. [Google Scholar]; c Liu C.; Shi C.; Mao F.; Xu Y.; Liu J.; Wei B.; Zhu J.; Xiang M.; Li J. Discovery of New Imidazole Derivatives Containing the 2,4-Dienone Motif with Broad-Spectrum Antifungal and Antibacterial Activity. Molecules 2014, 19, 15653–15672. 10.3390/molecules191015653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Babizhayev M. A. Biological activities of the natural imidazole-containing peptidomimetics n-acetylcarnosine, carcinine and L-carnosine in ophthalmic and skin care products. J. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 2343–2357. 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Sharma G. V. M.; Ramesh A.; Singh A.; Srikanth G.; Jayaram V.; Duscharla D.; Jun J. H.; Ummanni R.; Malhotra S. V. Imidazole derivatives show anticancer potential by inducing apoptosis and cellular senescence. Med. Chem. Commun. 2014, 5, 1751–1760. 10.1039/c4md00277f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Almirante L.; Polo L.; Mugnaini A.; Provinciali E.; Rugarli P.; Biancotti A.; Gamba A.; Mumann W. J. Derivatives of Imidazole. I. Synthesis and Reactions of Imidazo[1,2-α]pyridines with Analgesic, Antiinflammatory, Antipyretic, and Anticonvulsant Activity. J. Med. Chem. 1965, 8, 305–312. 10.1021/jm00327a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. G.; Kornfeld E. C.; McLaughlin K. C.; Anderson R. C. Studies on Imidazoles. IV.1The Synthesis and Antithyroid Activity of Some 1-Substituted-2-mercaptoimidazoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949, 71, 4000–4002. 10.1021/ja01180a036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg R. J.; Martin R. B. Interactions of histidine and other imidazole derivatives with transition metal ions in chemical and biological systems. Chem. Rev. 1974, 74, 471–517. 10.1021/cr60290a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuer K. D.; Fuchs A.; Ise M.; Spaeth M.; Maier J. Imidazole and pyrazole-based proton conducting polymers and liquids. Electrochim. Acta 1998, 43, 1281–1288. 10.1016/s0013-4686(97)10031-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Kwon O.-H.; Kim S.; Park S.; Choi M.-G.; Cha M.; Park S. Y.; Jang D.-J. Imidazole-Based Excited-State Intramolecular Proton-Transfer Materials: Synthesis and Amplified Spontaneous Emission from a Large Single Crystal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 10070–10074. 10.1021/ja0508727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. B.; Long T. E. Imidazole- and imidazolium-containing polymers for biology and material science applications. Polymer 2010, 51, 2447–2454. 10.1016/j.polymer.2010.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Van Leusen A. M.; Wildeman J.; Oldenziel O. H. Chemistry of sulfonylmethyl isocyanides. 12. Base-induced cycloaddition of sulfonylmethyl isocyanides to carbon, nitrogen double bonds. Synthesis of 1,5-disubstituted and 1,4,5-trisubstituted imidazoles from aldimines and imidoyl chlorides. J. Org. Chem. 1977, 42, 1153–1159. 10.1021/jo00427a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Pooi B.; Lee J.; Choi K.; Hirao H.; Hong S. H. Tandem Insertion–Cyclization Reaction of Isocyanides in the Synthesis of 1,4-Diaryl-1H-imidazoles: Presence of N-Arylformimidate Intermediate. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 9231–9245. 10.1021/jo501652w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cai Z.-J.; Wang S.-Y.; Ji S.-J. CuI/BF3·Et2O Cocatalyzed Aerobic Dehydrogenative Reactions of Ketones with Benzylamines: Facile Synthesis of Substituted Imidazoles. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 6068–6071. 10.1021/ol302955u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jiang Z.; Lu P.; Wang Y. Three-Component Reaction of Propargyl Amines, Sulfonyl Azides, and Alkynes: One-Pot Synthesis of Tetrasubstituted Imidazoles. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 6266–6269. 10.1021/ol303023y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Huang X.; Cong X.; Mi P.; Bi X.; Hong W. Azomethine-isocyanide [3+2] cycloaddition to imidazoles promoted by silver and DBU. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 3858–3861. 10.1039/c7cc00772h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Xiang L.; Niu Y.; Pang X.; Yang X.; Yan R. I2-catalyzed synthesis of substituted imidazoles from vinyl azides and benzylamines. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 6598–6600. 10.1039/c5cc01155h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Das U. K.; Shimon L. J. W.; Milstein D. Imidazole synthesis by transition metal free, base-mediated deaminative coupling of benzylamines and nitriles. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 13133–13136. 10.1039/c7cc08322j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Li J.; Zhang P.; Jiang M.; Yang H.; Zhao Y.; Fu H. Visible Light as a Sole Requirement for Intramolecular C(sp3)–H Imination. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 1994–1997. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Lee C. F.; Holownia A.; Bennett J. M.; Elkins J. M.; St. Denis J. D.; Adachi S.; Yudin A. K. Oxalyl Boronates Enable Modular Synthesis of Bioactive Imidazoles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 6264–6267. 10.1002/anie.201611006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhao H. Scaffold selection and scaffold hopping in lead generation: a medicinal chemistry perspective. Drug Discovery Today 2007, 12, 149–155. 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Patel S.; Harris S. F.; Gibbons P.; Deshmukh G.; Gustafson A.; Kellar T.; Lin H.; Liu X.; Liu Z.; Liu Y.; Ma C.; Scearce-Levie K.; Ghosh A. S.; Shin G.; Solanoy H.; Wang J.; Wang B.; Yin J.; Siu M.; Lewcock J. W. Scaffold-Hopping and Structure-Based Discovery of Potent, Selective, And Brain Penetrant N-(1H-Pyrazol-3-yl)pyridin-2-amine Inhibitors of Dual Leucine Zipper Kinase (DLK, MAP3K12). J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 8182–8199. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mamidala R.; Majumdar R.; Jha K. K.; Bathula C.; Agarwal R.; Chary M. T.; Majumder H. K.; Munshi P.; Sen S. Identification of Leishmania donovani Topoisomerase 1 inhibitors via intuitive scaffold hopping and bioisosteric modification of known Top 1 inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26603. 10.1038/srep26603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grealis J. P.; Müller-Bunz H.; Ortin Y.; Casey M.; McGlinchey M. J. Synthesis of Isobavachalcone and Some Organometallic Derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 332–347. 10.1002/ejoc.201201063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães P. J.; Carvalho D. O.; Cruz J. M.; Guido L. F.; Barros A. A. Fundamentals and health benefits of xanthohumol, a natural product derived from hops and beer. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 591–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhanh L.-Q.; Yang X.-W.; Zhang Y.-B.; Zhai Y.-Y.; Xu W.; Zhao B.; Liu D.-L.; Yu H.-J. Biotransformation of phlorizin by human intestinal flora and inhibition of biotransformation products on tyrosinase activity. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 936–942. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lei C.; Zhang L.-B.; Yang J.; Gao L.-X.; Li J.-Y.; Li J.; Hou A.-J. Macdentichalcone, a unique polycyclic dimeric chalcone from Macaranga denticulata. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 5475–5478. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.10.090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sha Y.; Shi Y.; Niu B.; Chen Q. Cochinchinenin C, a potential nonpolypeptide anti-diabetic drug, targets a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 49015–49023. 10.1039/c7ra09470a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Huang H.; Ji X.; Wu W.; Jiang H. Practical Synthesis of Polysubstituted Imidazoles via Iodine-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidative Cyclization of Aryl Ketones and Benzylamines. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 335, 170–180. 10.1002/adsc.201200582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Cao J.; Zhou X.; Ma H.; Shi C.; Huang G. A facile and efficient method for the synthesis of 1,2,4-trisubstituted imidazoles with enamides and benzylamines. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 57232–57235. 10.1039/c6ra08174f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadayat T. M.; Song C.; Shin S.; Bahadur C.; Magar T. T.; Bist G.; Shrestha A.; Thapa P.; Na Y.; Kwon Y.; Lee E.-S. Synthesis, topoisomerase I and II inhibitory activity, cytotoxicity, and structure–activity relationship study of 2-phenyl- or hydroxylated 2-phenyl-4-aryl-5H-indeno[1,2-b]pyridines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 3499–3512. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.