Abstract

Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) is an important polymer with stimuli-responsive properties, making it suitable for various uses. Phase behavior of the temperature-sensitive PNIPAM polymer in the presence of four low-molecular weight additives tert-butylamine (t-BuAM), tert-butyl alcohol (t-BuOH), tert-butyl methyl ether (t-BuME), and tert-butyl methyl ketone (t-BuMK) was studied in water (D2O) using high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and dynamic light scattering. Phase separation was thermodynamically modeled as a two-state process which resulted in a simple curve which can be used for fitting of NMR data and obtaining all important thermodynamic parameters using simple formulas presented in this paper. The model is based on a modified van’t Hoff equation. Phase separation temperatures Tp and thermodynamic parameters (enthalpy and entropy change) connected with the phase separation of PNIPAM were obtained using this method. It was determined that Tp is dependent on additives in the following order: Tp(t-BuAM) > Tp(t-BuOH) > Tp(t-BuME) > Tp(t-BuMK). Also, either increasing the additive concentration or increasing pKa of the additive leads to depression of Tp. Time-resolved 1H NMR spin–spin relaxation experiments (T2) performed above the phase separation temperature of PNIPAM revealed high colloidal stability of the phase-separated polymer induced by the additives (relative to the neat PNIPAM/D2O system). Small quantities of selected suitable additives can be used to optimize the properties of PNIPAM preparations including their phase separation temperatures, colloidal stabilities, and morphologies, thus improving the prospects for the application.

1. Introduction

Stimuli-responsive polymers, also called “smart polymers”, are a group of materials which are responsive to external stimuli due to variations in their hydrophilic–hydrophobic characters.1−5 Temperature, solvents, salts, pH, electromagnetic radiation, chemical, or biological agents are all potential stimuli which can trigger a response,1,5−7 and there are also a variety of responses, including conformational change, micelle formation, dissolution/precipitation, or variations in optical or electrical properties. Temperature-responsive polymers are well-known for their unique property to undergo phase separation upon temperature decrease (upper critical solution temperature behavior—UCST) or temperature increase (lower critical solution temperature behavior—LCST).7−16 The phenomenon of phase separation is due to a coil–globule transition, whereby the expanded coils of polymer chains undergo a transition to compact polymer globules. At the molecular level, phase separation in solutions is considered to be a macroscopic manifestation of a coil–globule transition followed by further aggregation and formation of colloidally stable mesoglobules.4,17,18 Phase separation is associated with variations in the balance between several types of interactions, including hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions.4 Prolonging the colloidal stability of phase-separated polymers is an important issue in applications such as controlled release, drug delivery, bioseparation, and diagnostics. It is still unclear, for some polymers, what is the main driving force behind their high colloid stability in thermodynamically unfavorable media.4

Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) is a well-known temperature-responsive polymer with LCST at approximately 32 °C,19 close to human body temperature. This makes PNIPAM-based systems interesting for various biomedical1,2,6,7,20−26 and technological8 applications. PNIPAM and its copolymers have been widely studied by means of light-scattering techniques,19,27 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy,3,28 refractometry,29 pressure perturbation calorimetry,30 differential scanning calorimetry,31−33 isothermal titration calorimetry,34 and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.10,27,28,33,35,36 The presence of low-molecular weight compounds such as salts37 or surfactants38 can shift the phase equilibrium of PNIPAM to higher or lower temperatures. PNIPAM can also undergo phase separation at a constant temperature by changing the ratio of two polar solvents (e.g., water–methanol, water–ethanol, and water–tetrahydrofuran), the so-called co-nonsolvency effect.15,39,40 These properties make PNIPAM attractive for various applications.

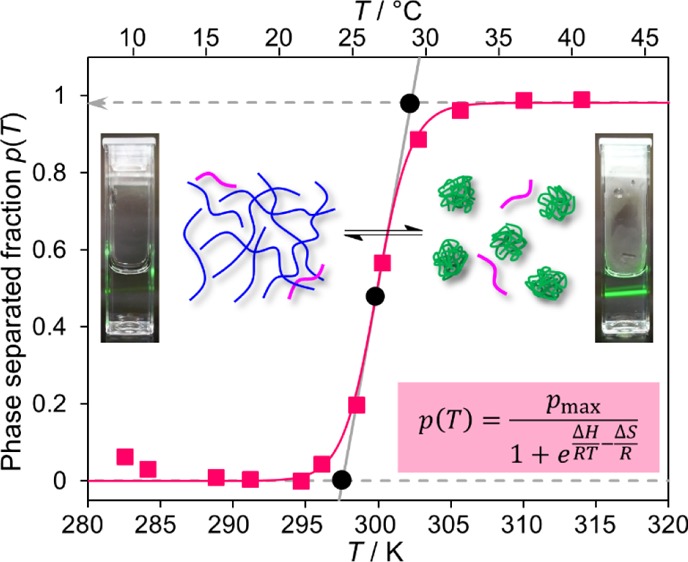

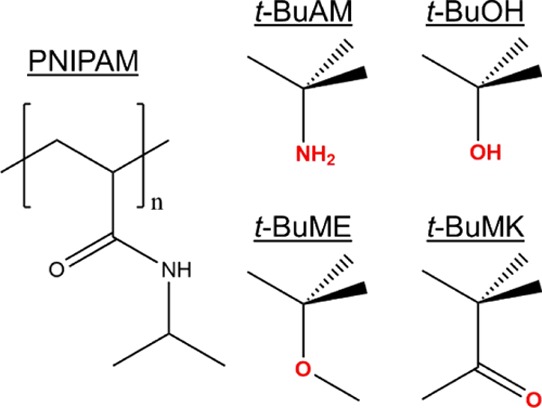

In this work, we provide a comparative analysis of the effects of low-molecular weight hydrophobic additives on the phase separation of PNIPAM. In particular, the behavior of PNIPAM in response to small quantities of tert-butyl alcohol (t-BuOH), tert-butylamine (t-BuAM), tert-butyl methyl ether (t-BuME), and tert-butyl methyl ketone (t-BuMK) additives has been investigated (Figure 1). NMR spectroscopy was used as the main technique for the analysis of the effects of additives on phase behavior with phase separation being modeled as a two-state dynamical process. The NMR data were rationalized in terms of a modified van’t Hoff equation fitted to experimental data. This approach allows determination of thermodynamic parameters such as the variations in enthalpy and entropy associated with phase separation. 1H NMR spin–spin relaxation experiments (T2) were used to examine the molecular mobility of the additives and D2O solvent molecules. Spin–spin relaxation times T2 provide information about the colloidal stability of phase-separated PNIPAM over time. The dynamic light scattering (DLS) technique was used to determine the sizes of polymer globules formed above the phase separation temperature.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of temperature-sensitive PNIPAM and the additives used in this study: tert-butylamine (t-BuAM), tert-butyl alcohol (t-BuOH), tert-butyl methyl ether (t-BuME), and tert-butyl methyl ketone (t-BuMK).

2. Results and Discussion

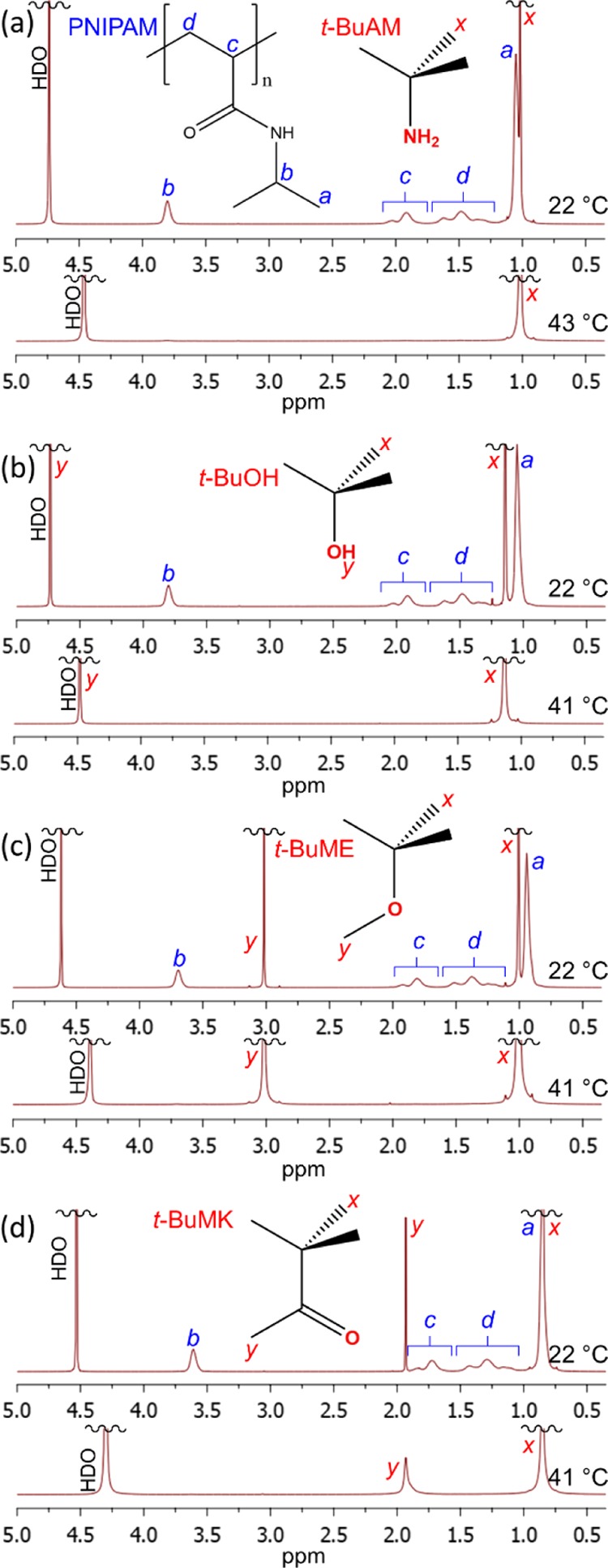

Examples of NMR spectra of PNIPAM (5 wt % in D2O) in the presence of the additives studied (2 wt % in D2O) below (22 °C) and above (∼41 °C) the phase separation temperature are shown in Figure 2. The spectra clearly indicate that after phase separation, the resonances due to PNIPAM (a, b, c, and d resonances in Figure 2) disappear. This effect is connected with the low mobility of PNIPAM globular structures above phase separation.

Figure 2.

1H NMR (600.2 MHz) of PNIPAM (wP = 5 wt %, D2O) below (at 22 °C) and above (at ca. 41 °C) the phase separation temperature in the presence of wadditive = 2 wt % of additives: (a) t-BuAM, (b) t-BuOH, (c) t-BuME, and (d) t-BuMK. Resonance assignments of PNIPAM and all additives are also shown for each case.

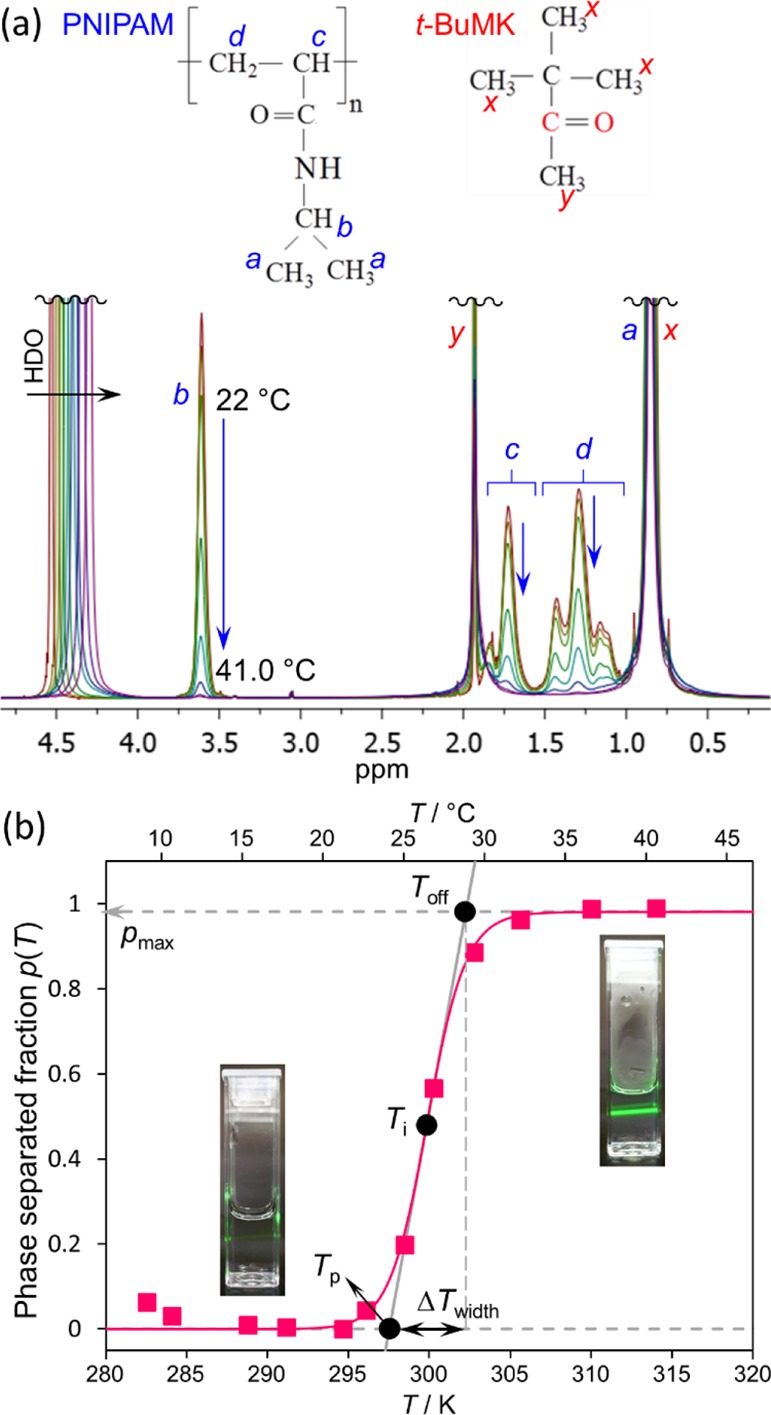

Figure 3a shows the 1H NMR spectra measured during heating at small temperature steps either side of the phase separation temperature. A gradual decrease in the resonance intensity due to PNIPAM can be observed. To perform the quantitative analyses of the phase separation, the value of the phase-separated fraction of PNIPAM units p(T) was calculated using the following formula.10,41−43

| 1 |

where I0′(T0) is temperature-dependent integrated intensity of the NMR resonance corresponding to polymers below the phase separation temperature (usually determined at T0 = 20 °C). The I′(T) is temperature-dependent integrated intensity of the same resonance in the partly phase-separated system (determined at T > 20 °C). The I0′(T0) and I′(T) values are unaffected by the fundamental temperature dependence of integrated intensities according to the Boltzmann equation. The Boltzmann equation states that the integrated intensities are temperature-dependent and decrease with absolute temperature as 1/T. This effect is corrected in eq 1 using the formulae I(T) = I′(T)/T and I0(T0) = I0′(T0)/T0, where I(T) and I0(T0) are Boltzmann-uncorrected integrated intensities as obtained from measurement of the partly phase-separated system and prior to phase separation, respectively. The “b” resonance corresponding to the NCH group of PNIPAM (Figure 3a) was used for evaluation of the integrated intensities and subsequent calculation of the phase-separated fraction. This yields the right side of eq 1 used for data analysis at temperatures T ≥ T0, where T is the actual temperature of measurement and T0 is the temperature below phase separation of PNIPAM. The results obtained using this method are plotted in Figure 3b (solid squares).

Figure 3.

(a) Superimposed 1H NMR (600.2 MHz) spectra of PNIPAM (wp = 5 wt %) with t-BuMK additive (wt-BuMK = 2 wt %) measured at temperatures about the phase separation temperature. Assignment of PNIPAM and t-BuMK signals is shown. (b) Phase separation fraction p(T) of PNIPAM polymer units (solid squares) as obtained from (a) using eq 1. The solid line is fit based on eq 6. Photos of solutions below and above phase separation (irradiated by a green laser pointer) are included.

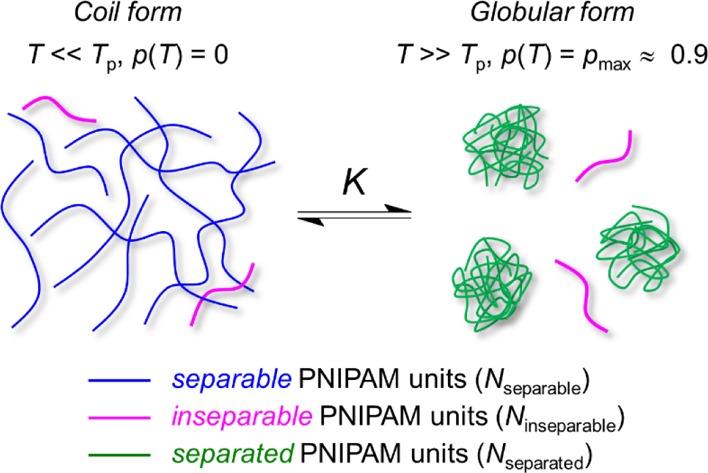

To extract the thermodynamic parameters of the phase separation of PNIPAM solutions from NMR data, we have used a simple model based on two exchangeable states41 (Figure 4). State one consists of polymer units in the coil form (a freely moving polymer chain). The second consists of polymer units in the globular form (rather compact rigid structures). The transition between these two states (coil–globule transition) is described by an equilibrium constant K, which is defined as the ratio of separated Nseparated and separable (but not separated yet) Nseparable PNIPAM units.

| 2 |

Figure 4.

Schematic model of phase separation of the PNIPAM polymer containing three types of units used for the thermodynamic model.

This model also takes into account that some polymer chains are not separable and remain in a coil state even at high temperatures (often attributed to the low molecular weight fractions of the polymer44), reflected by Ninseparable (i.e., number of inseparable PNIPAM units). The fraction of phase-separated PNIPAM units p(T) is generally defined in eq 3.

| 3 |

The combination of eqs 2 and 3 gives a formula for p(T) as a function of the equilibrium constant K

| 4 |

where pmax = (Nseparable + Nseparated)/(Nseparable + Ninseparable + Nseparated) is the maximum fraction of PNIPAM phase separable units. The van’t Hoff equation for the temperature dependence of the equilibrium constant K is shown in eq 5.

| 5 |

where ΔH and ΔS are the standard changes in enthalpy and entropy, respectively, connected with phase separation of PNIPAM. R is the gas constant (8.314 J mol–1 K–1) and T is the absolute temperature. Combining eqs 4 and 5 yields a final formula for p(T)41

| 6 |

Experimental data for p(T) as shown in Figure 3b were fitted using eq 6 such that values of ΔH and ΔS could be obtained. Another important parameter is the temperature of the phase separation Tp, calculated as the onset temperature obtained from fitting of the p(T) curve (see Figure 3b). The value of Tp is found at the intersection point of the tangent at the inflexion point Ti of the p(T) curve and the x-axis. The inflexion is at the point where the second derivative of p(T) is zero p″(T) = d2p(T)/dT2 = 0, resulting in the following eq 7

| 7 |

This equation does not have analytical solution in the closed form. Therefore, the numerical bisection method can be used for the determination of the inflexion point Ti. However, a solution of excellent accuracy can be found using an approximation. Equation 7 can be rearranged as eq 8.

| 8 |

where the term containing exponentials corresponds to the tanh function, subsequently approximated using the first term of its Taylor expansion (i.e., tanh(x) ≈ x). This yields a quadratic equation for Ti, eq 9

| 9 |

whose solution has the form of eq 10.

| 10 |

At this point, the Taylor expansion of the

square root up to the

second order term is used (i.e.,  ). After several rearrangements, a simple

formula for the temperature at the inflexion point Ti can be obtained.

). After several rearrangements, a simple

formula for the temperature at the inflexion point Ti can be obtained.

| 11 |

The condition for the intersection of the tangent line at the inflexion point and x-axis leads to an expression for the temperature of phase separation Tp.

| 12 |

where p′(Ti) denotes the first derivative of p(T) with respect to T evaluated at Ti. Using a similar approach, an equation for the offset temperature Toff (Figure 3b) can be derived from the intersection of the tangent line with line y = pmax.

| 13 |

The offset temperature Toff indicates the point at which phase separation is nearly complete. From Tp and Toff, the width of the phase separation ΔTwidth (the difference between offset and onset temperatures; see Figure 3b) can be determined using the following formula

| 14 |

The fitting of experimental data using eq 6 yields values for ΔH, ΔS, and pmax. Thereafter, the parameters Tp and ΔTwidth can be determined using eqs 12 and 14, respectively. Error analysis indicates that these approximations introduce only negligible errors into the values of Ti, Tp, Toff, and ΔTwidth obtained.a

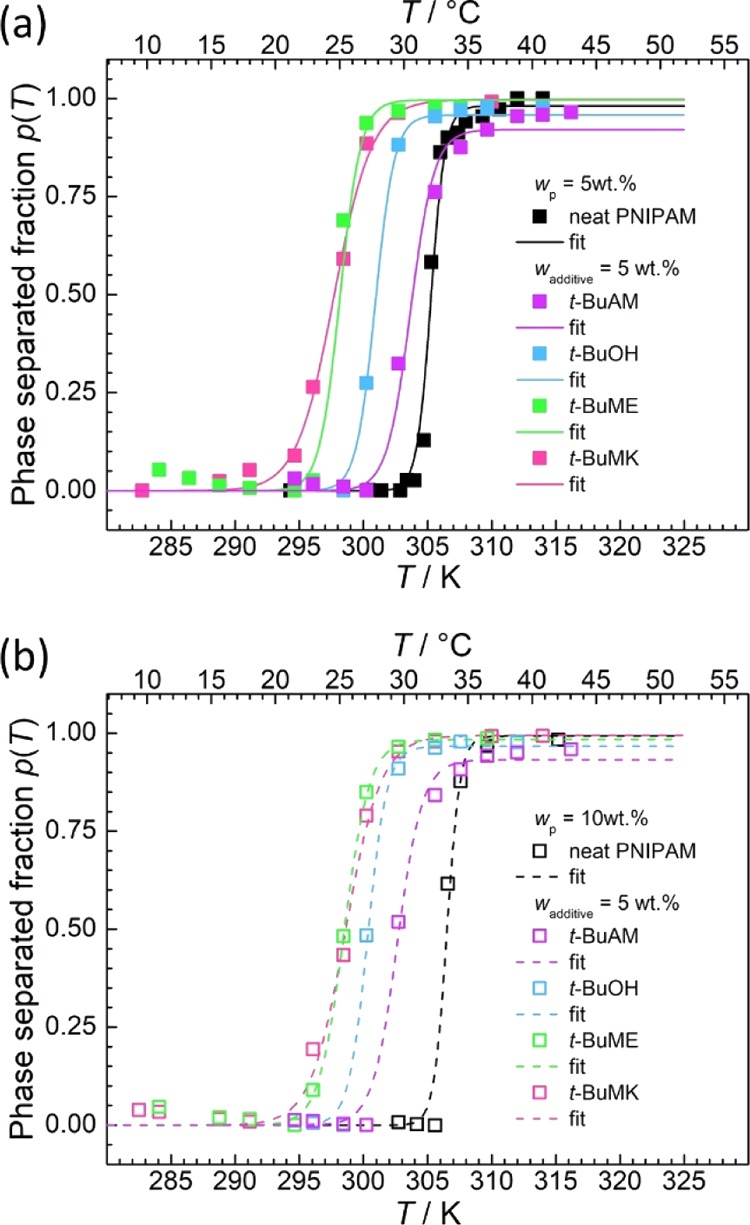

Figure 5 shows p(T) as calculated from NMR experimental data for samples of PNIPAM (5 and 10 wt %) and all additives (5 wt %). It can be seen that the phase separation temperature Tp decreases (for both PNIPAM concentrations), depending on the additive, in the following order: no additive > t-BuAM > t-BuOH > t-BuME > t-BuMK.

Figure 5.

Influence of additive types (wadditive = 5 wt %) on the phase-separated fraction p(T) of (a) wp = 5 wt % and (b) wp = 10 wt % of PNIPAM as obtained from the NCH resonance of PNIPAM. Key: Full/empty squares = experimental points, full/dashed lines = fits according to eq 6.

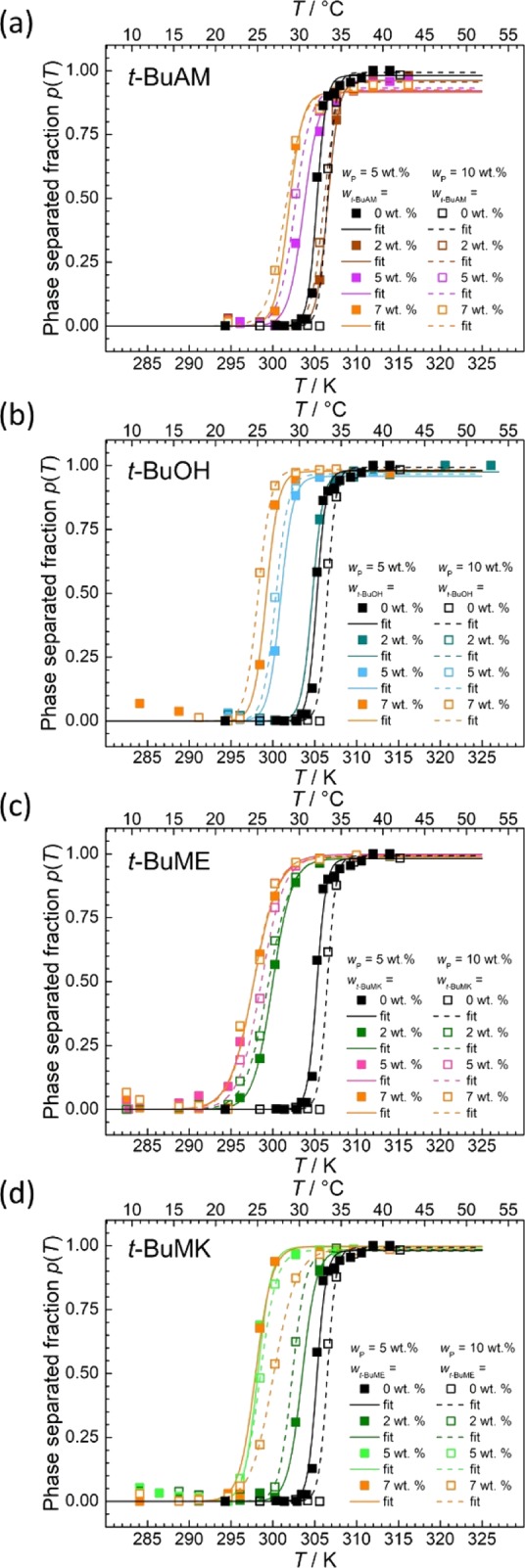

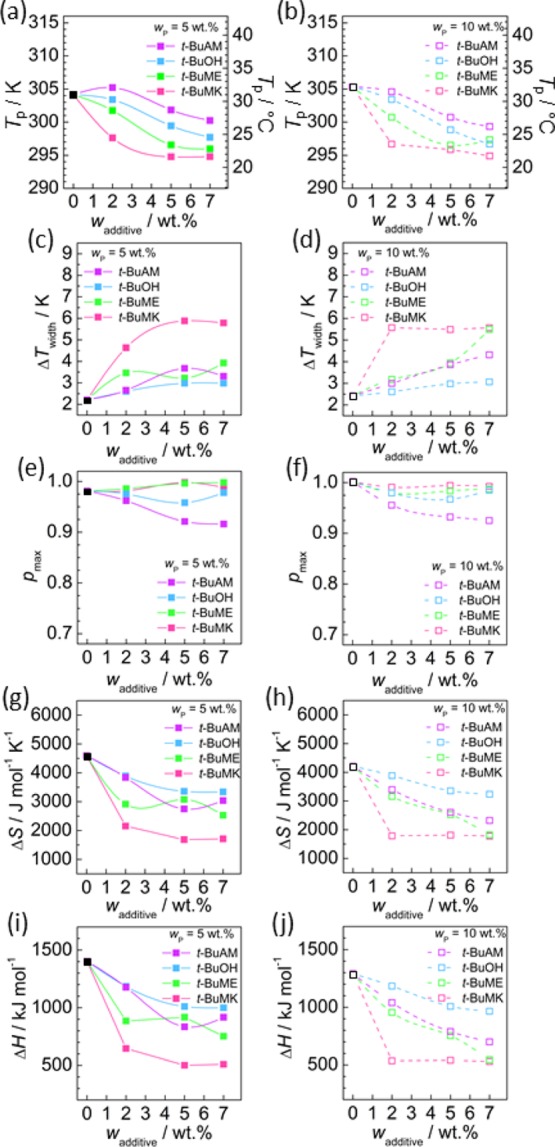

Figure 6 shows plots of the phase-separated fraction p(T) obtained from NMR data for all measured combinations of PNIPAM (5 and 10 wt %) and additives (0, 2, 5, and 7 wt %). The data were fitted using eq 6. All relevant thermodynamic parameters (Tp, ΔTwidth, pmax, ΔH, and ΔS) are graphically summarized in Figure 7. It can be seen that there are only small differences in all studied parameters for 5 and 10 wt % of PNIPAM. Increasing the content of any additive decreases the phase separation temperature (Tp, Figure 7a,b), increases the width of phase separation (ΔTwidth, Figure 7c,d), and decreases both enthalpy (ΔH, Figure 7g,h) and entropy change (ΔS, Figure 7i,j) connected with phase separation of PNIPAM. The value of Tp depends on the additive type and decreases in the following order (at constant wadditive): t-BuAM > t-BuOH > t-BuME > t-BuMK. t-BuMK has the greatest effect on Tp (decrease of ca. 10 °C), ΔTwidth, ΔH, and ΔS, which will be discussed in detail later. Values of pmax are close to 1 (within experimental error) for all additives (Figure 7e,f).

Figure 6.

Plots of phase-separated fraction p(T) as obtained from NCH resonances of PNIPAM (solid line 5 wt %; dashed line 10 wt %) with various concentrations of (a) t-BuAM, (b) t-BuOH, (c) t-BuME, and (d) t-BuMK. Key: Full/empty squares = experimental points, full/dashed lines = fits according to eq 6.

Figure 7.

Parameters characterizing phase separation of PNIPAM (5 and 10 wt %) in the presence of the additives studied as denoted in each panel. (a,b) Phase separation temperatures Tp. (c,d) Width of phase separation ΔTwidth. (e,f) Maximum fraction of phase-separated PNIPAM units pmax. (g,h) Variations in standard enthalpy, ΔH. (i,j) Variations in standard entropy, ΔS. Key: Solid and empty black squares correspond to 5 and 10 wt % PNIPAM solutions without additives, respectively.

The additives can be ordered in terms of relative hydrophobicity. Using the values of partition coefficients, log P (given in brackets for each additive) estimated using HSPiP software45 gives the order from least to most hydrophobic additives in the following sequence: t-BuAM (0.3) > t-BuOH (0.5) > t-BuME (0.9) > t-BuMK (1.2). From this perspective, the phase separation of PNIPAM is mostly affected by t-BuMK because of its hydrophobic association with PNIPAM. This association leads to the partial removal of water molecules from the vicinity of the polymer chains. This effect lowers Tp and ΔH because less heat is required to break hydrogen bonds between polymer chains and solvating water molecules.

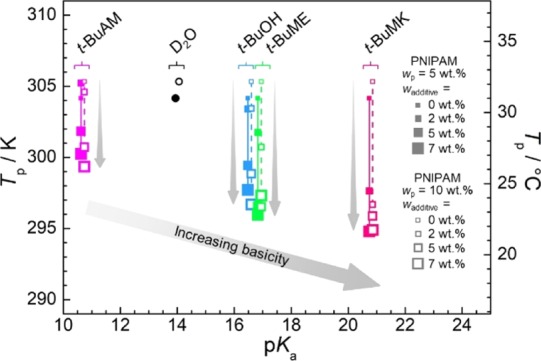

Acidity/basicity is another parameter characterizing these additives. Figure 8 is a plot of Tp as a function of pKa for each additive and its weight fraction. It can be seen that higher pKa (higher basicity) of the additive lowers Tp. Also, larger content of the same additive decreases the Tp value (vertical gray arrows in Figure 8). This is again because of the higher basicity of the solution. Therefore, pH of the aqueous solution significantly affects the phase separation temperature of PNIPAM.

Figure 8.

Plot of the phase separation temperature Tp (data from Figure 7a,b) as a function of pKa of additives and its content (wadditive) for both 5 and 10 wt % of PNIPAM. The values of pKa correspond to nondeuterated additives: t-BuAM (pKa = 10.68),46t-BuOH (pKa = 16.54),47t-BuME (pKa = 16.89),48 and t-BuMK (pKa = 20.8).49 The value of pKa for neat D2O is set to 14 (same as H2O) for consistency with additives. For clarity, there are slight offsets of additive pKa values for 5 and 10 wt % of PNIPAM. All values of pKa (in H2O) can be converted to pKa* (in D2O) using the approximate formula pKa = 1.076 × pKa – 0.45.50 However, this corresponds practically to a ca. +0.8 pKa unit shift (i.e., to more basic) of the experimental points, and so it does not change the character of the plot.

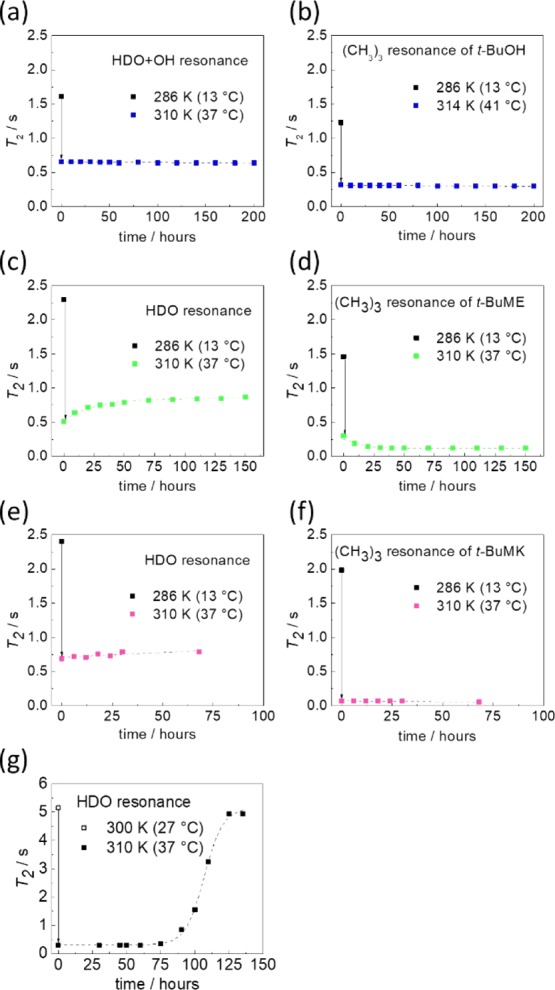

A series of time-resolved spin–spin 1H NMR relaxation experiments was performed in order to determine the mobilities of water and additive molecules below and above the phase separation temperature of PNIPAM (for wp = 5 wt %). The values of spin–spin 1H NMR relaxation time T2 were acquired for residual HDO and also for the t-butyl proton resonances of t-BuOH, t-BuME, and t-BuMK as shown in Figure 9. T2 relaxation times above phase separation (T = 310 K = 37 °C) were significantly shorter than those at the temperature (T = 286 K = 13 °C) below separation for both HDO and t-butyl (CH3)3 groups. This shows that HDO molecules as well as additive molecules exhibit a lower, spatially restricted mobility. Contributions due to chemical exchange16 are also important because the mobility-restricted solvent molecules are bound within mesoglobules and thus have a low T2 value. The overall T2 value is the weighted harmonic mean of bound and free T2 values, resulting in low overall T2 above phase separation.51 The sample was then kept in the NMR magnet at an elevated temperature (T = 310 K = 37 °C), and the time dependence of T2 was measured. After the value of T2 had reached a plateau, we observed no further changes of T2 values over the course of days (Figure 9a–f). T2 values remained relatively low (ca. 0.7 s for HDO and ca. 0.2 s for t-butyl groups of additives), indicating that the solvent molecules remain restricted in mobility and bound in mesoglobular structures. This further indicates that these systems are colloidally stable solutions, such that the phase-separated particles do not aggregate and precipitate. This observation is in contrast to the pristine PNIPAM/D2O system lacking any additive in which the T2 relaxation time after 130 h (5.5 days) recovers to its original value (Figure 9g).10 This corresponds to a state in which water, originally bound in mesoglobules, is very slowly released from these structures, making them more compact. Our observations indicate that the hydrophobic association of PNIPAM and the studied additive molecules increases the colloidal stability of phase-separated polymers sequestering the solvent molecules (both D2O and the additive) within the mesoglobular structure for extended periods (for at least 8 days in the case of t-BuOH). It seems that after phase separation, the additive (which hydrophobically associates with PNIPAM) acts as a shell around the mesoglobules with effective steric stabilizing properties,4 which prevents further aggregation and precipitation.

Figure 9.

Time dependency of spin–spin relaxation time T2 of HDO and (CH3)3 resonances of additives (wadditive = 5 wt %) below (T = 286 K = 13 °C) and above (T = 310 K = 37 °C) the phase separation temperature of PNIPAM (wp = 5 wt %). T2 values measured in the presence of (a,b) t-BuOH, (c,d) t-BuME, and (e,f) t-BuMK. (g) Pristine PNIPAM/D2O system (wp = 5 wt %). Data are taken from ref (10).

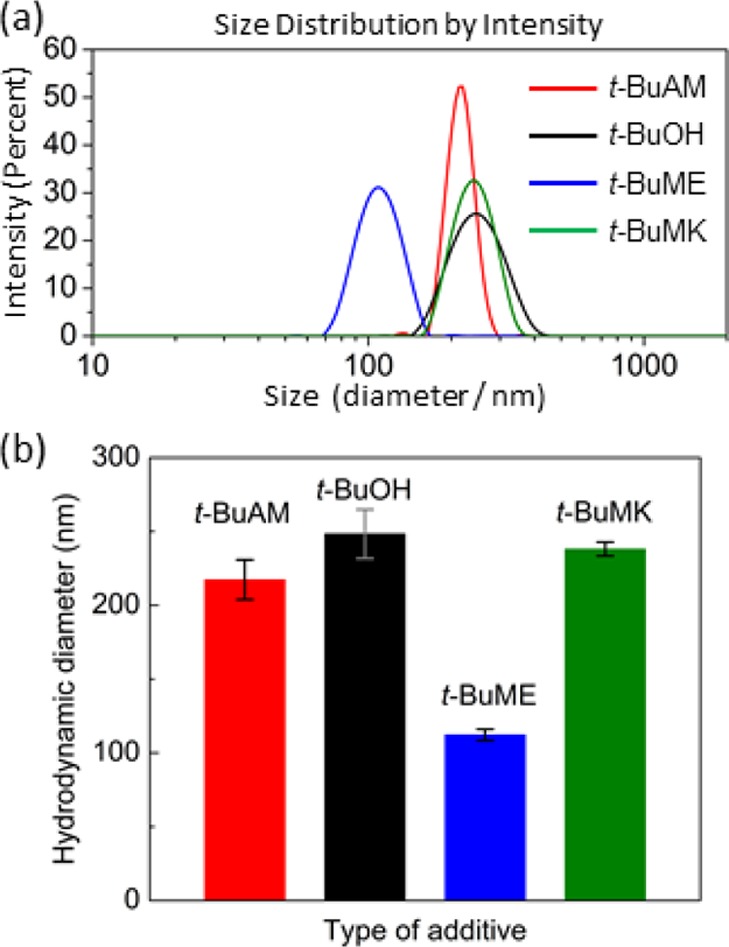

DLS data provide information about the size of PNIPAM globules in the presence of additives (t-BuAM, t-BuOH, t-BuME, or t-BuMK). There is no significant variation in the hydrodynamic diameters (∼230 nm) for t-BuAM, t-BuOH, and t-BuMK additives (Figure 10a). There is a relatively narrow distribution for t-BuAM, which might be caused by its Brønsted-type base character (capability of accepting protons), resulting in a different association mode with PNIPAM. For t-BuME additive, it was found that the particle size was smaller at around 110 nm in diameter (Figure 10b). This does not correlate with any additive property parameter such as hydrophobicity (log P) or acidity (pKa) and is probably caused by some specific structure-related intermolecular interactions between PNIPAM and t-BuME.

Figure 10.

(a) Distribution of hydrodynamic diameters of PNIPAM (wp = 0.015 wt %, D2O) with t-BuAM, t-BuOH, t-BuME, or t-BuMK (wadditive = 5 wt % for all additives) measured at 50 °C. (b) Plot of average values of hydrodynamic diameters.

3. Conclusions

In summary, we have reported the effect of low-molecular weight additives, such as t-BuAM, t-BuOH, t-BuME, or t-BuMK, on the phase behavior of the PNIPAM polymer in D2O solutions using NMR and DLS methods. Phase separation was modeled as a two-state process. NMR data were rationalized in terms of a modified van’t Hoff equation fitted to the experimental data. This allowed us to obtain accurate values of phase separation temperatures Tp and thermodynamic parameters, such as variations in enthalpy and entropy connected with the phase separation of PNIPAM. We have found that (depending on the additive type) the phase separation temperature Tp decreases (at a constant additive weight fraction) in the following order: Tp(t-BuAM) > Tp(t-BuOH) > Tp(t-BuME) > Tp(t-BuMK). Tp also decreases with an increasing concentration of additives. This effect is strongest for t-BuMK with a Tp decrease of ca. 10 °C relative to the pristine PNIPAM/D2O system. We found that the additives hydrophobically associate with the PNIPAM chain, leading to the removal of water molecules from the solvating shell of polymers, thus lowering the enthalpy change of phase separation. An interesting correlation between the pKa of additives and the phase separation temperature Tp of PNIPAM, that higher pKa (i.e., higher basicity) leads to lower Tp, was also found. Time-resolved 1H NMR spin–spin relaxation experiments (T2) above the phase separation temperature revealed that when PNIPAM is in a mesoglobular state, there is no change in the restricted mobility of solvent molecules over the course of days. This indicates the high colloidal stability of phase-separated polymers, with trapping of the solvent molecules (both D2O and additives) within its structure. This effect is in contrast to the PNIPAM/D2O system lacking additives in which the majority of water is released from mesoglobules within 5 days. Therefore, a small quantity of a suitable additive can be used for the tuning of PNIPAM properties, such as phase separation temperature, colloidal stability, and morphology/dimensions of formed mesoglobules. Improvements in the stabilities of colloidal solutions of PNIPAM or similar polymers ought also to improve their attractiveness for various applications either simply because of possibilities for extending the stable shelf lives of preparations or because of the tunability of phase separation properties within the physiologically important temperature range.

4. Materials and Methods

PNIPAM (Mw = 19 000–26 000 g/mol) (see Figure 1 for the structure) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. D2O (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.9% of deuterium) was used for sample preparation. tert-Butyl alcohol (t-BuOH), tert-butylamine (t-BuAM), tert-butyl methyl ether (t-BuME), and tert-butyl methyl ketone (t-BuMK) (see Figure 1 for the structures) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. All samples were sealed in 5 mm NMR tubes. The weight fraction of PNIPAM in the binary solvent D2O/additive was calculated as wp = mp/(mp + mD2O + madditive) × 100% (in wt %), where mp, mD2O, and madditive are masses of the PNIPAM polymer, D2O, and additives, respectively. The composition of the binary solvent D2O/additive was determined by the weight fraction of an additive in D2O/additive solution as wadditive = madditive/(mD2O + madditive) × 100% (in wt %).

High-resolution 1H NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker AVANCE III 600 spectrometer operating at 600.2 MHz. During measurements at different temperatures, receiver gain was kept constant to obtain comparable values of integrated intensities. The 1H spin–spin relaxation times T2 were measured using a CPMG pulse sequence of 90x° – (td – 180y° – td)n—acquisition with a half-echo time td = 5 ms. Each experiment was performed over 4 scans with a relaxation delay between scans of 120 s. The resulting T2 relaxation curves are monoexponential. The fitting process made it possible to determine consistently a single value of the relaxation time. The relative error of T2 values of the HDO and the additive (CH3)3 groups did not exceed ±8%. During measurement, temperature was maintained constant within ±0.2 K using a BVT 3000 temperature unit. Prior to each measurement, samples were equilibrated for about 15 min at the measurement temperature.

The hydrodynamic diameter Dh (z-average) and size distribution of polymer assemblies in deuterated water (D2O) (wp = 0.015 wt %) were determined at 50 °C using a ZEN 3600 Zetasizer Nano Instrument (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The data were subsequently analyzed using the supplied Malvern Instruments software. Prior to measurement, samples were filtered using a 0.22 μm polyvinylidene fluoride filter to remove any interfering dust particles. Each measurement consisted of an average of five scans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the World Premier International Research Initiative (WPI Initiative), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. The authors also acknowledge Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic, for the support given to N. V. during doctoral studies.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Footnotes

Comparison of exact numerical solution of eq 7 (Tiexact) with approximate solution described by eq 11 (Ti) shows that for ΔH ≥ 105 J mol–1 and ΔS ≥ 200 J mol–1 K–1, the error is |Tiexact – Ti| < 0.04 K. The lower boundary of ΔH and ΔS is chosen as an extreme case far from experimentally obtained values. For higher values of ΔH and ΔS, the error in determination of Ti using the approximate formula further decreases. Subsequently, errors calculated (using exact and approximate values of Ti) for the phase separation temperature [Tp; eq 12] and the width of the phase separation [ΔTwidth; eq 14] are |Tpexact – Tp| < 10–4 K and |ΔTwidthexact – ΔTwidth| < 10–4 K, respectively. Therefore, the approximations used here introduce only negligible errors.

References

- Schmaljohann D. Thermo- and pH-responsive polymers in drug delivery. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2006, 58, 1655–1670. 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón C. d. l. H.; Pennadam S.; Alexander C. Stimuli responsive polymers for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 276–285. 10.1039/b406727d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H.; Shen L.; Wu C. LLS and FTIR studies on the hysteresis in association and dissociation of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) chains in water. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 2325–2329. 10.1021/ma052561m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aseyev V. O.; Tenhu H.; Winnik F. M. Temperature dependence of the colloidal stability of neutral amphiphilic polymers in water. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2006, 196, 1–85. 10.1007/12_052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jochum F. D.; Theato P. Temperature- and light-responsive smart polymer materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7468–7483. 10.1039/c2cs35191a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong B.; Gutowska A. Lessons from nature: stimuli-responsive polymers and their biomedical applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2002, 20, 305–311. 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)01962-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward M. A.; Georgiou T. K. Thermoresponsive polymers for biomedical applications. Polymers 2011, 3, 1215–1242. 10.3390/polym3031215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.; Fraylich M.; Saunders B. R. Thermoresponsive copolymers: from fundamental studies to applications. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2009, 287, 627–643. 10.1007/s00396-009-2028-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spěváček J.; Starovoytova L.; Hanyková L.; Kouřilová H. Polymer-solvent interactions in solutions of thermoresponsive polymers studied by NMR and IR spectroscopy. Macromol. Symp. 2008, 273, 17–24. 10.1002/masy.200851303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Starovoytova L.; Spěváček J. Effect of time on the hydration and temperature-induced phase separation in aqueous polymer solutions. 1H NMR study. Polymer 2006, 47, 7329–7334. 10.1016/j.polymer.2006.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spěváček J.; Dybal J. Stimuli-responsive polymers in solution investigated by NMR and infrared spectroscopy. Macromol. Symp. 2011, 303, 17–25. 10.1002/masy.201150503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spěváček J.; Dybal J.; Starovoytova L.; Zhigunov A.; Sedláková Z. Temperature-induced phase separation and hydration in poly(N-vinylcaprolactam) aqueous solutions: a study by NMR and IR spectroscopy, SAXS, and quantum-chemical calculations. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 6110–6119. 10.1039/c2sm25432h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spěváček J.; Hanyková L.; Labuta J. Behavior of water during temperature-induced phase separation in poly(vinyl methyl ether) aqueous solutions. NMR and optical microscopy study. Macromolecules 2011, 7, 2149–2153. 10.1021/ma200010h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kouřilová H.; Št’astná J.; Hanyková L.; Sedláková Z.; Spěváček J. 1H NMR study of temperature-induced phase separation in solutions of poly(N-isopropylmethacrylamide-co-acrylamide) copolymers. Eur. Polym. J. 2010, 46, 1299–1306. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2010.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kouřilová H.; Spěváček J.; Hanyková L. 1H NMR study of temperature-induced phase transitions in aqueous solutions of poly(N-isopropylmethacrylamide)/poly(N-vinylcaprolactam) mixtures. Polym. Bull. 2013, 70, 221–235. 10.1007/s00289-012-0831-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kouřilová H.; Hanyková L.; Spěváček J. NMR study of phase separation in D2O/ethanol solutions of poly(N-isopropylmethacrylamide) induced by solvent composition and temperature. Eur. Polym. J. 2009, 45, 2935–2941. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2009.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishige S.; Kubota K.; Ando I. Phase transition of aqueous solutions of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) and poly(N-isopropylmethacrylamide). J. Phys. Chem. 1989, 93, 3311–3313. 10.1021/j100345a085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aseyev V.; Hietala S.; Laukkanen A.; Nuopponen M.; Confortini O.; Du Prez F. E.; Tenhu H. Mesoglobules of thermoresponsive polymers in dilute aqueous solutions above the LCST. Polymer 2005, 46, 7118–7131. 10.1016/j.polymer.2005.05.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heskins M.; Guillet J. E. Solution properties of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide). J. Macromol. Sci., Part A: Pure Appl. Chem. 1968, 2, 1441–1455. 10.1080/10601326808051910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monerris M.; Broglia M.; Yslas I.; Barbero C.; Rivarola C. Antibacterial polymeric nanocomposites synthesized by in-situ photoreduction of silver ions without additives inside biocompatible hydrogel matrices based on N-isopropylacrylamide and derivatives. eXPRESS Polym. Lett. 2017, 11, 946–962. 10.3144/expresspolymlett.2017.91. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brun-Graeppi A. K. A. S.; Richard C.; Bessodes M.; Scherman D.; Merten O.-W. Thermoresponsive surfaces for cell culture and enzyme-free cell detachment. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2010, 35, 1311–1324. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2010.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin A.; Kröger M.; Winnik F. M. Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) Phase Diagrams: Fifty Years of Research. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 15342–15367. 10.1002/anie.201506663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann C. H.; Schönhoff M. Dynamics and distribution of aromatic model drugs in the phase transition of thermoreversible poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) in solution. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2012, 290, 689–698. 10.1007/s00396-011-2577-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav S. A.; Scalarone D.; Brunella V.; Ugazio E.; Sapino S.; Berlier G. Thermoresponsive copolymer-grafted SBA-15 porous silica particles for temperature-triggered topical delivery systems. eXPRESS Polym. Lett. 2017, 11, 96–105. 10.3144/expresspolymlett.2017.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. M.; Zheng S. X.; Chang H. I.; Tsai H. Y.; Liang M. Microwave-assisted synthesis of thermo- and pH-responsive antitumor drug carrier through reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymerization. eXPRESS Polym. Lett. 2017, 11, 293–307. 10.3144/expresspolymlett.2017.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi A.; Paul A.; Sen S. O.; Sen K. K. Studies on thermoresponsive polymers: Phase behaviour, drug delivery and biomedical applications. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 10, 99–107. 10.1016/j.ajps.2014.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filippov S. K.; Bogomolova A.; Kaberov L.; Velychkivska N.; Starovoytova L.; Cernochova Z.; Rogers S. E.; Lau W. M.; Khutoryanskiy V. V.; Cook M. T. Internal nanoparticle structure of temperature-responsive self-assembled PNIPAM-b-PEG-b-PNIPAM triblock copolymers in aqueous solutions: NMR, SANS, and light scattering studies. Langmuir 2016, 32, 5314–5323. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b00284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starovoytova L.; Spěváček J.; Trchová M. 1H NMR and IR study of temperature-induced phase transition of negatively charged poly(N-isopropylmethacrylamide-co-sodium methacrylate) copolymers in aqueous solutions. Eur. Polym. J. 2007, 43, 5001–5009. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2007.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp M.; Aleksandrova R.; Müller U.; Ostermeyer M.; Sanctuary R.; Müller-Buschbaum P.; Krüger J. K. Molecular versus macroscopic perspective on the demixing transition of aqueous PNIPAM solutions by studying the dual character of the refractive index. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 7297–7305. 10.1039/c4sm01222d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa P.; Winnik F. M. Volumetric Studies of Aqueous Polymer Solutions Using Pressure Perturbation Calorimetry: A New Look at the Temperature-Induced Phase Transition of Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) in Water and D2O. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 4130–4135. 10.1021/ma002082h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y.; Yang J.; Ding Y.; Ye X. Effect of urea on phase transition of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) investigated by differential scanning calorimetry. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 9460–9466. 10.1021/jp503834c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiktopulo E. I.; Uversky V. N.; Lushchik V. B.; Klenin S. I.; Bychkova V. E.; Ptitsyn O. B. Domain Coil-Globule Transition in Homopolymers. Macromolecules 1995, 28, 7519–7524. 10.1021/ma00126a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Št’astná J.; Hanyková L.; Spěváček J. NMR and DSC study of temperature-induced phase transition in aqueous solutions of poly(N-isopropylmethacrylamide-co-acrylamide) copolymers. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2012, 290, 1811–1817. 10.1007/s00396-012-2701-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shechter I.; Ramon O.; Portnaya I.; Paz Y.; Livney Y. D. Microcalorimetric study of the effects of a chaotropic salt, KSCN, on the lower critical solution temperature (LCST) of aqueous poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPA) solutions. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 480–487. 10.1021/ma9018312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann C.; Schönhoff M. Do additives shift the LCST of poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) by solvent quality changes or by direct interactions?. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2009, 287, 1369–1376. 10.1007/s00396-009-2103-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Starovoytova L.; Spěváček J.; Ilavský M. 1H NMR study of temperature-induced phase transitions in D2O solutions of poly(N-isopropylmethacrylamide)/poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) mixtures and random copolymers. Polymer 2005, 46, 677–683. 10.1016/j.polymer.2004.11.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Furyk S.; Bergbreiter D. E.; Cremer P. S. Specific Ion Effects on the Water Solubility of Macromolecules: PNIPAM and the Hofmeister Series. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14505–14510. 10.1021/ja0546424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L.-T.; Cabane B. Effects of surfactants on thermally collapsed poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) macromolecules. Macromolecules 1997, 30, 6559–6566. 10.1021/ma9704469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winnik F. M.; Ottaviani M. F.; Bossmann S. H.; Pan W.; Garcia-Garibay M.; Turro N. J. Cononsolvency of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide): a look at spin-labeled polymers in mixtures of water and tetrahydrofuran. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 4577–4585. 10.1021/ma00069a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pica A.; Graziano G. An alternative explanation of the cononsolvency of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) in water-methanol solutions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 25601–25608. 10.1039/c6cp04753j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velychkivska N.; Bogomolova A.; Filippov S. K.; Starovoytova L.; Labuta J. Thermodynamic and kinetic analysis of phase separation of temperature-sensitive poly(vinyl methyl ether) in the presence of hydrophobic tert-butyl alcohol. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2017, 295, 1419–1428. 10.1007/s00396-017-4100-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labuta J.; Hill J. P.; Hanyková L.; Ishihara S.; Ariga K. Probing the micro-phase separation of thermo-responsive amphiphilic polymer in water/ethanol solution. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2010, 10, 8408–8416. 10.1166/jnn.2010.3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spěváček J.; Hanyková L. NMR Study on polymer-solvent interactions during temperature-induced phase separation in aqueous polymer solutions. Macromol. Symp. 2007, 251, 72–80. 10.1002/masy.200750510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spěváček J.; Hanyková L.; Starovoytova L. 1H NMR relaxation study of thermotropic phase transition in poly(vinyl methyl ether)/D2O solutions. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 7710–7718. 10.1021/ma0486647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen Solubility Parameters in Practice (HSPiP) software. http://www.pirika.com/NewHP/PirikaE/logP.html (web page accessed on Aug 27, 2018).

- Juranić I. Simple method for the estimation of pKa of amines. Croat. Chem. Acta 2014, 87, 343–347. 10.5562/cca2462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve W.; Erikson C. M.; Aluotto P. F. A new method for the determination of the relative acidities of alcohols in alcoholic solutions. The nucleophilicities and competitive reactivities of alkoxides and phenoxides. Can. J. Chem. 1979, 57, 2747–2754. 10.1139/v79-444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett E. M.; Wu C. Y. Base strengths of some aliphatic ethers in aqueous sulfuric acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962, 84, 1680–1684. 10.1021/ja00868a037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zook H. D.; Kelly W. L.; Posey I. Y. Chemistry of enolates. VI. Acidity scale for ketones. Effect of enolate basicity in elimination reactions of halides. J. Org. Chem. 1968, 33, 3477–3480. 10.1021/jo01273a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krżel A.; Bal W. A formula for correlating pKa values determined in D2O and H2O. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2004, 98, 161–166. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanyková L.; Labuta J.; Spěváček J. NMR study of temperature-induced phase separation and polymer-solvent interactions in poly(vinyl methyl ether)/D2O/ethanol solutions. Polymer 2006, 47, 6107–6116. 10.1016/j.polymer.2006.06.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]