Abstract

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) is a popular material in membrane field because of its excellent mechanical property, thermal stability, and chemical resistance. Unfortunately, PAN nanofibers produced by electrospinning are not suitable for interfacial polymerization process directly due to its hydrophobicity and large average pore size. In this work, the cross-linked chitosan (CS) solution was coated on the nanofiber surface to fabricate a sublayer, based on which thin-film composite (TFC) membranes were prepared using m-phenylenediamine and 1,3,5-trimesoyl chloride as the monomers. The impact of the different sublayers on the performances of TFC PAN nanofiber membranes for forward osmosis (FO) was studied by varying cross-linked CS concentrations. The results indicated that the increased CS concentration not only led to the relatively denser polyamide layer, but also changed its morphology. In the reverse osmosis process, NaCl rejection increased from 46.5 to 83.5%. Salt flux from feed solution to draw solution decreased from 25.8 to 8.9 g·m–2·h–1 (0.1 M NaCl solution as feed, 2 M glucose solution as draw solution, FO mode). This study found that the sublayer had noteworthy impact on the separation layer and helped us to pave the way to design high-performance FO membranes.

1. Introduction

Water scarcity has become one of the most serious issues around the world due to continuous industrialization and population growth.1 Researchers have implemented several measures to increase water supply, such as desalination and water reuse.2 Membrane processes (e.g., reverse osmosis (RO) and nanofiltration (NF)) are believed to be effective and economical due to their versatility, low investment of equipment, and easy operation.3 RO is now the most popular desalination process, comprising 61% of the global share, followed by multistage flash at 26% and multieffect distillation at 8%.4 After the rapid development in the past 2 decades, however, the energy required to separate potable water from seawater has nearly reached the theoretical minimum energy of desalination.5 Therefore, the pretreatment and post-treatment stages of the large-scale seawater reverse osmosis plants have been focused to improve the energy efficiency. Forward osmosis (FO) as an emerging technology capable of extracting water from feed solution (FS) (low osmotic pressure) into draw solution (DS) (high osmotic pressure) can achieve high water recovery as hybrid systems with RO.2

Thin-film composite (TFC) nanofiber membranes prepared by interfacial polymerization (IP) have been very attractive for constructing high-efficiency composite membranes. Similar to RO and NF membranes, most of FO membranes were fabricated in the type of TFC membranes. Generally, TFC membranes have a multitier structure: a top layer responsible for the separation of water and solute, an asymmetric porous support layer providing a platform for IP, and a nonwoven substrate that gives mechanical support for high hydraulic pressure operation (Figure 1A). Furthermore, TFC membrane is one of the most widely applied types as both the selective and support layers can be individually adjusted for specific needs.6−8 Nevertheless, the difference lies in the design criteria of membranes.9 In the traditional membrane processes driven by the hydraulic pressure, generally the polyamide top layer, dominating the membrane performance (permeate flux, rejection, antifouling properties, and the chemical durability), has received much more attention than the support layer.10,11 When RO or NF membranes were applied in the FO process, the membrane performances were far lower than expected values.12,13 This phenomenon is mainly attributed to internal concentration polarization (ICP), which reduced effective osmotic driving force and created severe flow resistance within thick and dense support layers.14 Hence, it is necessary to redesign a new form of a support layer specifically for FO processes. Nanofibers fabricated by electrospinning technology have attracted tremendous attention in water filtration due to their desirable properties for FO process, such as relatively high porosity and interconnected pores with uniform pore sizes.15,16 Compared to conventional phase inversion membranes, the more open structures of nanofibers provide a different platform for the IP. McCutcheon’s group found that the polyamide layer delaminated from polyethersulfone nanofibers easily due to the poor adhesion between the polyamide and nanofibers.17 Wang et al. prepared TFC FO membranes with two different surface pore sizes of poly(vinylidene difluoride) nanofiber substrates.18 By comparing the two cases, the larger pore sizes of nanofibers would decrease the cross-linking of the polyamide layer. Thus, the large pore sizes and porosity endow the TFC membranes with the high permeation while sacrificing the salt rejections. Other researchers have addressed this issue by considering hydrophilic materials for their favorable wettability to improve the salt rejection. Huang et al. fabricated hydrophilic nylon 6,6 nanofibers as the support layer.19 Preferable performances were achieved, but it should also be noted that these nanofibers were subjected to swelling when exposed to water, meaning there were dramatic decreases in mechanical strength. In addition, the results of poly(vinyl alcohol) nanofibers also proved that the pressure resistance of hydrophilic nanofibers should be enhanced, especially under high-pressure operation.20

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the traditional three-layered TFC membranes (A) and a novel three-layered composite TFC membrane presented in this work (B).

To the address the mechanical stability problem of hydrophilic nanofiber support, our previous study adopted hydrophobic (water contact angle: 108°) polyimide (PI) microporous nanofiber as support. However, we found that polyamide layer could not be formed directly on the PI nanofiber surface. Thus, a novel polymerization procedure involving two IP procedures was developed to address this problem.21 Although the polyamide layer was successfully synthesized according to the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images, the salt rejection was comparatively unsatisfactory. Moreover, there are only a few studies on how the polyamide layer affected by the pore size of support membrane influences FO performance. Some previous research works have proved that the cross-linking of the polyamide layer is closely related to the pore size of the support layer, thus leading to the different salt rejections and performances.18,22 Although the supports with different pore sizes were synthesized with the same material in the studies, other properties were different, such as thickness, porosity, and tortuosity, which also could affect FO performance. It was uncertain whether these performance differences were mainly caused by the polyamide layers or the supports themselves.

In this study, we also found that the hydrophobic polyacrylonitrile (PAN) nanofibers were not suitable for IP process.20 Therefore, we introduced a new concept of a three-layered composite membrane introducing a cross-linked chitosan (CS) sublayer onto hydrophobic PAN microporous nanofibers to facilitate the IP process (Figure 1B). The cross-linked CS layer not only improved the wettability of the hydrophobic nanofibers, but also provided the smooth and uniform surface for the IP. Aiming at reducing ICP, the thickness of the membranes was controlled without any backing layers (nonwoven substrates). The degree of cross-linked CS layer was tailored by changing the glutaraldehyde (GA) and CS concentrations. The intrinsic permeability properties and FO performance of the TFC–CS–PAN membranes were examined. As these TFC FO membranes had identical supports, the role of the polyamide layer alone on the FO performance was explored without the disturbance of supports. We found that sublayer inserted between supporting layer and separation layer had a noteworthy impact on the separation layer, thereby leading to different performances.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Morphologies of Support Layers and Active Layers

The uniform PAN nanofibers were successfully fabricated by electrospun, and their average diameter is 397.5 ± 46.3 nm from Figure 2A. Considering the electrospun PAN nanofibers are hydrophobic (water contact angle can be 128°), it is difficult to form well-distributed liquid layer when the aqueous phase is poured onto the nanofiber surface.23 There are large holes (>1 μm) on the surface, which is inappropriate for the IP procedures. As a result, the resultant TFC membrane has low NaCl rejection after the IP procedure. Therefore, it is necessary that nanofibers should be modified before the IP reaction. First, the unmodified nanofiber supports were prewetted by the CS solution to prevent the penetration of the cross-linked CS solution, which was consistent with the observation from Figure 2E,F. When the CS–GA concentration increased, the cross-linked layers covered the nanofiber network and the nanofibers became invisible (Figure 2C,D). This indicated that the cross-linked CS layers were successfully coated on the surface of PAN nanofibers.

Figure 2.

SEM images of four CSGA–PAN membranes: (A) top surface of CSGA–PAN-1 (magnification 10k×); (B) top surface of CSGA–PAN-2 (magnification 10k×); (C) top surface of CSGA–PAN-3 (magnification 10k×); (D) top surface of CSGA–PAN-4 (magnification 10k×); (E) cross section of CSGA–PAN-3 (magnification 30k×); and (F) cross section of CSGA–PAN-4 (magnification 30k×).

The top surface and cross-sectional SEM images for polyamide selective layers of TFC–CS–PAN membranes are shown in Figures 3 and 4. All TFC–CS–PAN membranes possess typical ridge-and-valley structure without any defects from Figure 3. Figure 4 shows that the polyamide selective layers have strong adhesion with the supports. This might contribute to the chemical interaction between trimesoyl chloride (TMC) and the cross-linked CS layer. According to the attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectra of the CSGA–PAN membranes and the structural composition of CS, it was certain that −NH2 groups did exist on the surface of the CSGA–PAN membranes. Other research works also reported that heat treatment could induce the further cross-linking reaction between the residual unreacted amine and acyl chloride groups.24,25 Thus, when the TMC solution was poured on the m-phenylenediamine (MPD)-impregnated support, the −COCl groups of TMC not only reacted with the −NH2 groups of MPD, but also with those of CS.26 As a result, the newly formed byproduct of the IP, −CONH, had generated good adhesion between the polyamide layer and cross-linked CS layer. The average thickness of the polyamide layers is approximately 100 nm for all four supports. Generally, no notable morphological difference is observed on the top surface and cross-sectional SEM images due to the same IP procedures.

Figure 3.

Top surface SEM images of four TFC–CS–PAN membranes: (A) TFC–CS–PAN-1 (magnification 10k×); (B) TFC–CS–PAN-1 (magnification 50k×); (C) TFC–CS–PAN-2 (magnification 10k×); (D) TFC–CS–PAN-2 (magnification 50k×); (E) TFC–CS–PAN-3 (magnification 10k×); (F) TFC–CS–PAN-3 (magnification 50k×); (G) TFC–CS–PAN-4 (magnification 10k×); and (H) TFC–CS–PAN-4 (magnification 50k×).

Figure 4.

Cross-sectional SEM images of four TFC–CS–PAN membranes: (A) TFC–CS–PAN-1 (magnification 5k×); (B) TFC–CS–PAN-1 (magnification 30k×); (C) TFC–CS–PAN-2 (magnification 5k×); (D) TFC–CS–PAN-2 (magnification 30k×); (E) TFC–CS–PAN-3 (magnification 5k×); (F) TFC–CS–PAN-3 (magnification 30k×); (G) TFC–CS–PAN-4 (magnification 5k×); and (H) TFC–CS–PAN-4 (magnification 30k×).

Therefore, the surface morphologies of the TFC–CS–PAN membranes and the CSGA–PAN membranes were further characterized by atomic force microscopy (AFM). As described in Figure 5, forming smoother cross-linked CS layer leads to a decrease of the roughness of nanofiber surface in terms of Ra and Rmax, which results in a slight decrease of the roughness of polyamide layer. These results indicate a good agreement with the SEM images.

Figure 5.

AFM images and data of TFC–CS–PAN membranes and CSGA–PAN membranes.

2.2. Chemical Composition of CSGA–PAN and TFC–CS–PAN Membranes

The ATR-FTIR spectra in Figure 6 confirm the presence of the cross-linked CS layer and polyamide layer. Characteristic peaks of PAN are located at 2243.3 and 2243.0 cm–1 representing −C≡N stretching.6 Compared to PAN nanofibers, the peaks of CSGA–PAN-4 at 1651.1 and 1559.2 cm–1 ascribed to amide −C=O (amide I peak) and −N–H (amide II peak) become stronger due to the cross-linking of CS chains.6 The absence of the peak at 1590 cm–1 (−NH2 band) also confirms the occurrence of cross-linking reaction between GA and the NH2 groups.27−29 The emerging peak of TFC–CS–PAN-4 at 1610.9 cm–1 could be attributed to the aromatic amide of the polyamide layer.30 Moreover, the peak at 2243 cm–1 almost disappears in the spectra of TFC–CS–PAN-4, which also indicates that the polyamide layer and the cross-linked CS layer are flawless and shield the −C≡N stretching from being characterized by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy.

Figure 6.

ATR-FTIR spectra of the (a) PAN nanofibers, (b) cross-linked CS, (c) CSGA–PAN-4, and (d) TFC–CS–PAN-4 membranes.

The formation scheme of polyamide (Figure 7) shows that a polyamide layer usually consists of the cross-linking and linear structure. In this formation scheme, X represents the cross-linking portion of the resulting polyamide and Y represents the linear part. If X = 1, the O/N ratio is 1 and the resultant polyamide is fully cross-linking. Similarly, when Y = 1, the O/N ratio is 2 and the resultant polyamide is fully linear.31 The relative atomic fractions and the cross-linking degrees of the polyamide layer are presented in Table 1. The cross-linking degree of the active layer could be estimated from following eqs 3 and 4

| 1 |

| 2 |

On the basis of the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) results, the cross-linking portions increase from 0.11 to 0.80 with increasing CS and GA concentrations. In other words, smaller pore size result in higher cross-linking degree of active layers, thus affecting membrane performances.

Figure 7.

Formation scheme of polyamide.

Table 1. Relative Atomic Fractions Determined by XPS and the Cross-Linking Degrees of the Four Polyamide Layers.

| membranes | C (%) | O (%) | N (%) | other (%) | O/N | X value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFC–CS–PAN-1 | 69.05 | 17.77 | 9.64 | 3.54 | 1.84 | 0.11 |

| TFC–CS–PAN-2 | 71.14 | 17.20 | 9.83 | 1.83 | 1.75 | 0.18 |

| TFC–CS–PAN-3 | 68.51 | 17.35 | 11.45 | 2.69 | 1.52 | 0.39 |

| TFC–CS–PAN-4 | 73.55 | 13.50 | 11.79 | 1.16 | 1.15 | 0.80 |

2.3. Water Contact Angles and Mechanical Property

Figure 8 shows the water contact angles of PAN nanofibers and CSGA–PAN and TFC–CS–PAN membranes. The water contact angles decrease significantly from 132° for PAN nanofibers to 45–61° for CS-coated membranes, implying that the membrane surface becomes more hydrophilic. This could be attributed to abundant hydrophilic groups like −NH2 and −OH groups on the cross-linked CS layers. The improvement of the hydrophilicity together with the smoother surface of cross-linked CS layers might be beneficial to the IP processes. Compared to those of CSGA–PAN, the water contact angles of the TFC–CS–PAN membranes increase to 72–75°. The reason might be that relatively more hydrophobic polyamide layers had covered the hydrophilic groups of the cross-linked CS layers. Moreover, the fact that the larger roughness has an effect on the enhancement of the surface hydrophilicity accounts for this phenomenon.32,33

Figure 8.

Water contact angles of PAN nanofibers and CSGA–PAN and TFC–CS–PAN membranes.

Table 2 shows that the PAN nanofibers have excellent mechanical properties. Only a slight reduction in the mechanical properties was observed when nanofibers were tested in wet states. Therefore, these modified nanofibers could avoid the swelling state when exposed in water and become an appropriate candidate for water treatment.

Table 2. Mechanical Properties of the PAN Nanofibers Tested in Dry and Wet States.

| test items | dry | wet |

|---|---|---|

| break strength (MPa) | 8.8 ± 0.5 | 7.3 ± 0.3 |

| Young’s modulus (MPa) | 730.0 ± 65.0 | 660.0 ± 53.0 |

| elongation at break (%) | 54.5 ± 8.0 | 48.5 ± 7.0 |

2.4. RO Performance

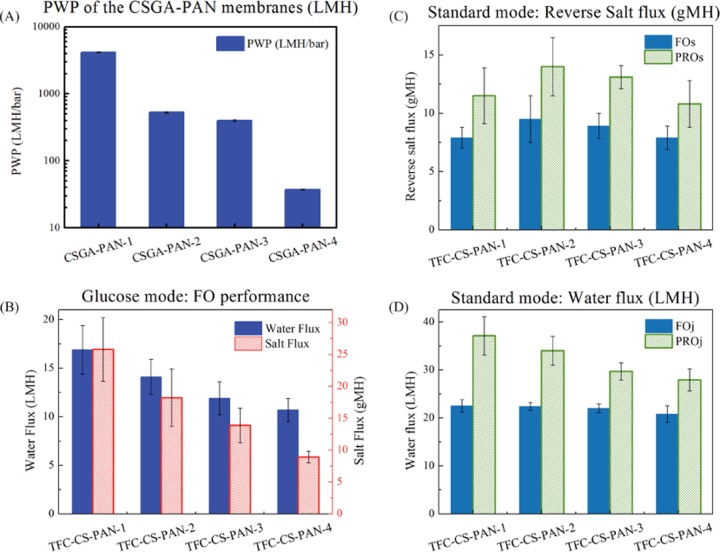

The PAN nanofibers and CSGA–PAN membranes were first tested under RO mode. The PAN nanofibers’ pure water permeability (PWP) can be as high as 10 283 ± 992 L·m–2·h–1·bar–1 (LMH·bar–1), which exhibits superior PWP. This should ascribe to the water transport pathway provided by the unique scaffold-like structure with high porosity and low tortuosity. Also the hydrophobic property weakens the interaction between water molecules and the pathway; thus, flow resistance is reduced and water molecules slide through the pathway.34 As shown in Figure 9, the average pore sizes of the PAN nanofibers and CSGA–PAN membranes are 483, 463, 452, 305, and 24.1 nm. Increasing the CS and GA concentrations in cross-linking CS solution can dramatically minimize the pore sizes of membranes surface and make preparations for next IP procedures.

Figure 9.

Pore size distribution and average pore size: (A) PAN nanofibers (483 nm), CSGA–PAN-1 (463 nm), CSGA–PAN-2 (452 nm), and CSGA–PAN-3 (305 nm) and (B) CSGA–PAN-4 (24.1 nm).

Figure 9A,B presents the permeabilities of water and NaCl, respectively. As revealed in Table 3, the performances of TFC–CS–PAN membranes follow the same trend as those of the CSGA–PAN membranes. Pure water permeance A decreases with decreasing pore sizes of the support. On the other hand, NaCl rejections gradually increase with decreasing pore size. Considering the fact that the morphologies and kinds of functional groups are similar among these TFC–CS–PAN membranes, the performance differences might be caused by the cross-linking degree difference. According to the XPS results (Table 1), the higher X value means the more aromatic amides of the cross-linking portion presented in the polyamide layer. Therefore, TFC–CS–PAN membranes based on the support with smaller pore size exhibited a lower water permeation and a higher NaCl rejection.

Table 3. RO Performance of the TFC FO Membranes.

| membranes | A (LMH·bar–1) | B (LMH) | rejection (NaCl %) | S* (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFC–CS–PAN-1 | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 11.5 ± 0.9 | 46.5 ± 1.0 | 350 |

| TFC–CS–PAN-2 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 59.9 ± 2.9 | 378 |

| TFC–CS–PAN-3 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 66.0 ± 4.5 | 349 |

| TFC–CS–PAN-4 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.41 ± 0.1 | 83.5 ± 2.8 | 298 |

2.5. FO Performance of the Standard Mode

Figure 10C,D reveals the FO performances of water flux (Jv) and reverse salt flux (Js) in standard mode. Unexpectedly, the differences of the FO performance seem less significant compared to those of the RO performance. Jv decreases 24.8% and Js is 6.0% in PRO mode, while the PWP decreases 75% and NaCl rejection increases 37% under RO mode. The reason might be that the substrate plays a more important role in the FO process than that in the RO process. In the RO process, the water flux and salt rejection are dominated by the active layers, while the substrates merely provide the mechanical support.35 The concentration polarization of both internal and external can be ignored when the feed concentration is not very high.36 However, when it comes to the FO process, Jv and Js are affected by both the active layer and the substrate due to the fact that driving force is the osmotic pressure difference across the membranes.37 Let us take FO mode as an example. When the active layer is placed against the feed solution (AL-FS mode, named as FO mode as well), the membrane surface osmotic pressure (πD,m) on the permeate side was diluted and found to be inevitably lower than the bulk draw osmotic pressure (πD,b). In the meantime, the membrane surface osmotic pressure (πF,m) on the feed side was concentrated and higher than the bulk feed osmotic pressure (πF,b). Therefore, the experimental osmotic pressure difference (ΔπE = πD,m – πF,m) across the membranes would be lower than the theoretical one (ΔπT = πD,b – πF,b).37

Figure 10.

Membrane performance: (A) PWP of the CSGA–PAN membranes, (B) FO performance of the glucose mode, (C) water flux of the standard mode, and (D) reverse salt flux of the standard mode.

When the pore sizes of the TFC–CS–PAN membranes decrease, the flow resistance increases and Jv should decrease accordingly. Meanwhile, it also results in the higher salt rejection, meaning that less amounts of salt passed through the selective layers and the πF,m was less concentrated. Therefore, the new osmotic pressure difference (ΔπE′) was closer to ΔπT. In other words, the driving force should be higher. Moreover, considering that flow direction of Js is opposite to that of Jv, decreasing Jv facilitates Js.38,39 As shown in Figure 11A, Jv and Js of the standard mode are affected not only by the flow resistance but also by each other. In fact, the decreasing effect of the increased flow resistance on Jv and Js has been counteracted by the increase of driving force to some extent. As a result, the changes of FO performances are not so significant as those of RO performances.

Figure 11.

FO process of (A) the standard mode and (B) the glucose mode.

2.6. FO Performance of the Glucose Mode

In practical FO applications, the feed solution cannot be the deionized (DI) water that has little osmotic pressure and the draw solution can be other kinds of solutes that have smaller diffusion coefficient than NaCl.40,41 Moreover, the aforementioned discussions indicate that the FO performance of the standard mode had inherent limitations. To address these issues, the glucose mode (2 M glucose solution as draw solution, 0.1 M NaCl solution as feed, FO mode) was adopted to measure the FO performance. In this mode, water and salt (NaCl, Js) have the same flow direction, which is from the feed to the draw solution. Glucose is chosen as draw solution for several reasons: (i) given that the molecular weight of glucose is 180.16 g·mol–1, even the TFC–CS–PAN-1 with the lowest NaCl rejection (46.5%) have >95% rejection of glucose. Compared to Js, the reverse salt flux (glucose) can be ignored; (ii) the osmotic pressure of the 2 M glucose is 55 atm, which is close to the osmotic pressure (47 atm) of 1 M NaCl.42,43

Figure 11B demonstrates the FO process of the glucose mode. When flow resistance increases, Jv and Js decrease 65.5 and 36.7%, respectively, indicating that the pore sizes of the polyamide layer become smaller. And the data were also close to the 75% decrease of the PWP and 37% increase of the NaCl rejection under RO mode. Due to the same flow direction of the water and salt flux, the salt flux is no longer suppressed by the water flux. Furthermore, the decreasing Js also indicate that less amounts of salt reach the membrane surface on the draw solution side and πF,m becomes smaller. From this perspective, the driving force is reduced. Another noteworthy thing is that the Jv of glucose mode is lower than that of standard mode although the driving force is almost same. It should be related to the different diffusion coefficient of the draw solutes. Glucose as draw solution with larger molecular weight has the lower diffusion coefficient (0.7 × 10–9 m2·s–1) and is more likely affected by ICP than NaCl (1.4 × 10–9 m2·s–1).40,41

For the proper evaluation of FO glucose performance of the introduced membranes, the comparison of other reported membranes is summarized in Table 4. Water flux of the TFC–CS–PAN membranes is relatively high compared to the other membranes when glucose is draw solution and DI water or low-concentration NaCl is feed solution. Overall, the introduced method to fabricate membranes expands FO membrane industrial applications and produces commercial FO membranes with high water flux and salt rejection.

Table 4. Water Fluxes and NaCl Rejections (RO) of Various Flat-Sheet TFC Membranes.

| sample | Jv (LMH) | rejection (NaCl %) | test condition | refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFC–CS–PAN-3 | 11.9 | 66.0 | feed: 0.1 M NaCl | this work |

| TFC–CS–PAN-4 | 10.7 | 83.5 | draw: 2.0 M glucose | |

| M 13 | 11.0 | 88.1–89.7 | feed: 0.1 M NaCl | (44) |

| HTI FO membrane | 7.8 | 90.2–92.6 | draw: 2.0 M glucose | |

| coated composite membrane | 3.8 | 55.0 | feed: DI water | (45) |

| draw: 1.0 M glucose | ||||

| CA membrane with poly(ethylene terephthalate) mesh embedded | 3.5 | N/A | feed: 0.2 M NaCl | (46) |

| draw: 1.5 M glucose | ||||

| CTA/CA membrane | 7.5 | N/A | feed: 0.5 M NaCl | (47) |

| draw: 2 M glucose |

3. Conclusions

In this work, a sublayer of cross-linked CS fabricated on the hydrophobic PAN microporous nanofibers could facilitate the IP process and have a significant impact on membrane performances. Using these identical PAN nanofibers as supports, the role of the polyamide layers as a singular independent variable was focused. Generally, we found that increasing the CS–GA concentrations not only decreased the pore sizes of the sublayer, but also changed the surface properties. On this basis, the formed polyamide layers became more selective and led to different RO and FO performances. Therefore, introducing the sublayer into the selective layer and supporting layer could be an alternative method when designing new membranes (Figures 12 and 13).

Figure 12.

Structural composition of CS.

Figure 13.

Fabrication process of TFC–CS–PAN membranes.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN, 500 kDa) was supplied from Shanghai Jinshang Petroleum Co. Ltd. m-Phenylenediamine (MPD, A.R., ≥99%), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, A.R., ≥99%), N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc, A.R., ≥99%), hexane (C6H14, A.R., ≥99.5%), glutaraldehyde (GA, 25%), chitosan (CS, 80.0–95.0% deacetylated, viscosity: 50–800 mPa·s, 600–700 kDa), sodium chloride (NaCl, A.R., ≥99.5%), acetic acid (C2H4O2, A.R., ≥99.5%), and sodium dodecyl benzenesulfonate (SDBS, C.P., ≥85.0%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. Trimesoyl chloride (TMC, ≥98%) were purchased from Qingdao Benzo Chemical Company (China). Deionized (DI) water was prepared in our lab.

4.2. Fabrication of PAN Nanofibers

The method we used to fabricate the PAN nanofibers is modification of the previous published work.48,49 PAN powder (10 wt %) was dissolved in a co-solvent system of DMAc and DMF with 1:1 weight ratio under room temperature to obtain a homogeneous solution. A 10.0 mL of the as-prepared solution was placed into a syringe pump and electrospun onto a piece of paper using a laboratory-scale electrospinning system, and the specific experimental conditions of PAN electrospinning are summarized in Table 5. After 4.5 h electrospun time, the pristine nanofiber mat was peeled off and then sandwiched between two pieces of paper and laminated through a paper laminator (no. 3893, Deli, China) at 120 °C to improve the mechanical property and obtain the smooth surface for further preparation of polyamide barrier layer. Thicknesses of the membranes were determined using a digital microcaliper, and they decreased from 80 ± 5 to 60 ± 3 μm after 120 °C hot-pressing (Table 6).

Table 5. Experimental Conditions of PAN Nanofibers Fabrication.

| sample | PAN (wt %) | DMAc (wt %) | DMF (wt %) | voltage potential (kV) | tip-collector distance (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAN nanofibers | 10 | 45 | 45 | 15–16 | 15 |

Table 6. Experimental Conditions of CSGA–PAN Membranes Fabrication.

| CS solution |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample | CS (g) | water (mL) | acetic acid (mL) | GA solution (g) | GA/CS (wt/wt) |

| CSGA–PAN-1 | 1.25 | 198 | 2 | 4.0 | 0.8 |

| CSGA–PAN-2 | 1.50 | 198 | 2 | 4.8 | |

| CSGA–PAN-3 | 1.75 | 198 | 2 | 5.6 | |

| CSGA–PAN-4 | 2.00 | 198 | 2 | 6.4 | |

4.3. Surface Modification with CS

The modification method involves cross-linking of CS and GA. CS powder was dissolved in a 200 mL mixture of water and acetic acid and stirred at 50 °C for 4 h to obtain a homogenous solution. The CS solution was poured onto the as-electrospun nanofibers for 20 min and then placed upside down during the drying process in ambient temperature to remove the redundant CS solution on the surface. In the meantime, a certain amount of GA solution was added into the 200 mL CS solution for cross-linking for 20 min and then the GA–CS solution was poured onto the CS side of the composite nanofibers for another 20 min, followed by removing the excessive GA–CS solution and drying thoroughly. The GA–CS solution contains 1.25, 1.50, 1.75, and 2.0 g of CS with the addition of 4, 4.8, 5.6, and 6.4 g GA, respectively. For convenience, these composite membranes were denoted CSGA–PAN-1, CSGA–PAN-2, CSGA–PAN-3, and TFC–CSGA–PAN-4, respectively.

4.4. IP of Polyamide Layer

The selective layer was prepared by the conventional IP method.17 TMC (0.15 wt %, n-hexane as solvent) solution and MPD (3.0 wt %, pure water as solvent, SDBS 0.1 wt % as surfactant) solution were used for the IP. Sodium dodecyl benzenesulfonate (SDBS), like sodium dodecyl sulfate, is a common type of surfactant.50 They can lower the interfacial tension due to their amphiphilic nature.51 Therefore, we believe that the use of SDBS can improve the wettability of the support, promote monomer migration to the interface region, and enhance the efficiency of the polymerization.52 First, the side of the modified nanofiber mats was contacted by the MPD solution for 300 s. Excess MPD solution was removed from the support surface using an air knife. The nanofiber supports were then dipped into TMC solution for 120 s to form the polyamide film. The resulting composite membranes were subsequently cured in an oven at 80 °C for 5 min for further polymerization. The TFC–CS–PAN membranes were thoroughly washed and stored in DI water at ambient temperature. Likewise, these TFC membranes were named as TFC–CS–PAN-1, TFC–CS–PAN-2, TFC–CS–PAN-3, and TFC–CS–PAN-4, respectively.

4.5. Characterizations

The water contact angles (θ) of nanofiber membranes were measured by a contact angle meter (JC2000A, provided by Shanghai Zhong Cheng Digital Equipment Co., Ltd., China). Five different locations for the membranes were subjected to the droplet of 2 μL water. All samples were tested three times and averaged. The morphologies of the membranes were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) images. The nanofiber membranes were coated with Pd via sputtering before being examined by a scanning electron microscope (JEOL, JSM-5600LV). The average fiber diameter of the nanofibers was determined by measuring 20 different fibers. The roughness of the membrane’s top surface was characterized by AFM (Nanoscope IIIa Multimode) with a scanning area of 5.0 μm × 5.0 μm. The surface chemical composition of membranes was characterized by an ATR-FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet Corporation). The mechanical property was evaluated using QJ210A (Shanghai Qingji Instrument Technology Co. Ltd., China). Membranes were cut into rectangular stripes of 4.0 cm × 1.5 cm dimensions and pulled in tension at a constant elongation speed with an initial length of 2.0 cm. The total porosity ε (%) of the resultant membranes is determined by the gravimetric method as defined in the following equation

| 3 |

where m1 (g) is the weight of the wet membrane without excess water on the surface, m2 (g) is the weight of the dry membrane, ρw (g·cm–3) is the water density, and ρp (g·cm–3) is the polymer density.

4.6. Evaluation of Membrane Performance

A laboratory-made cross-flow RO testing unit (2 bar) was used to evaluate the intrinsic properties, which were the pure water permeability (A) (PWP, L·m–2·h–1·bar–1, abbreviated as LMH·bar–1) and the observed salt rejection (Rs). Both of them can determine the salt permeability (B) (L·m–2·h–1, abbreviated as LMH) of prepared TFC membrane described elsewhere.53 The feed concentration (1000 ppm NaCl) and the salt concentration were measured using a DDS-11A conductance meter (Shanghai Neici Instrument Company, China). Both A and B are the intrinsic properties and are used to derive the structural parameter of the membranes.54 The average pore sizes and distributions of PAN nanofibers, CSGA–PAN-1, CSGA–PAN-2, and CSGA–PAN-3 were determined by the bubble-pressure method (Beishide Instrument 3H-2000PB, China), while CSGA–PAN-4’s were characterized by the solute transport of a 100 mg·L–1 dextran (molecular weight 40k–2000k) solution via ultrafiltration experiments.55,56

The FO performance was determined by two kinds of process. In the standard process, 1.0 mol·L–1 (M) NaCl solution was used as draw solution (DS) and DI water was used as the feed solution (FS). Osmotic flux tests were carried out in both FO (the active layer faces the feed solution) and pressure-retarded osmosis (PRO, the active layer faces the draw solution) mode. The water flux (Jv, L·m–2·h–1, abbreviated as LMH) was defined as the volume change of feed solutions per unit time and unit area. Similarly, the reverse salt flux (Js, g·m–2·h–1, abbreviated as gMH) from the draw solution to the feed solution was calculated by dividing the NaCl mass flow rate by the membrane area and test time. The structural parameter (S) can be determined by the following equation modified without considering the effect of external concentration polarization in the PRO process54

| 4 |

where Ds is the diffusion coefficient of the draw solute, Jw is the measured osmotic flux, A is the pure water permeability, B is the solute permeability, and πdraw and πfeed are the osmotic pressure of the bulk draw solution and feed solution, respectively.

In another process, denoted as glucose mode, 2.0 M aqueous glucose solution was used as draw solution (DS) and 0.1 M NaCl solution was used as the feed solution (FS). Osmotic flux tests were carried out in FO mode. Different from standard mode, the salt flux (Js) of glucose mode was from the feed solution to the draw solution, which was also detected by the conductance meter in the draw solution.

4.7. Instrumentation

Scanning electron microscope (JEOL, JSM-5600LV), atomic force microscope (Nanoscope IIIa Multimode), ATR-FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet Corporation), contact angle meter (JC2000A, provided by Shanghai Zhong Cheng Digital Equipment Co., Ltd., China). The mechanical property was evaluated using QJ210A (Shanghai Qingji Instrument Technology Co. Ltd., China). RO and FO testing units were made in our lab.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2015M571513) and the National Science and Technology Support Project of China (2014BAB07B01 and 2015BAB09B01).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Service R. F. Desalination Freshens Up. Science 2006, 313, 1088–1090. 10.1126/science.313.5790.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon M. A.; Bohn P. W.; Elimelech M.; Georgiadis J. G.; Marinas B. J.; Mayes A. M. Science and technology for water purification in the coming decades. Nature 2008, 452, 301–10. 10.1038/nature06599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. B.; Freeman B. D.; Zhang Z. B.; Sankir M.; McGrath J. E. Highly chlorine-tolerant polymers for desalination. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6019–24. 10.1002/anie.200800454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darre N. C.; Toor G. S. Desalination of Water: a Review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2018, 4, 104–111. 10.1007/s40726-018-0085-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elimelech M.; Phillip W. A. The future of seawater desalination: Energy, technology, and the environment. Science 2011, 333, 712–717. 10.1126/science.1200488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S.-F.; Dong Y.; Zheng Y.-M.; Zhong L.-B.; Yuan Z.-H. Self-sustained hydrophilic nanofiber thin film composite forward osmosis membranes: Preparation, characterization and application for simulated antibiotic wastewater treatment. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 523, 205–215. 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.09.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G.-R.; Xu J.-M.; Feng H.-J.; Zhao H.-L.; Wu S.-B. Tailoring structures and performance of polyamide thin film composite (PA-TFC) desalination membranes via sublayers adjustment-a review. Desalination 2017, 417, 19–35. 10.1016/j.desal.2017.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue S.-M.; Ji C.-H.; Xu Z.-L.; Tang Y.-J.; Li R.-H. Chlorine resistant TFN nanofiltration membrane incorporated with octadecylamine-grafted GO and fluorine-containing monomer. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 545, 185–195. 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.09.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W.; Chen Q.; Ge Q. Recent advances in forward osmosis (FO) membrane: Chemical modifications on membranes for FO processes. Desalination 2017, 419, 101–116. 10.1016/j.desal.2017.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Q.-C.; Wang J.; Wang X.; Chen B.-Z.; Guo J.-L.; Jia T.-Z.; Sun S.-P. A hydrophilicity gradient control mechanism for fabricating delamination-free dual-layer membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 539, 392–402. 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Q.-C.; Liu M.-L.; Cao X.-L.; Wang Y.; Xing W.; Sun S.-P. Structure design and applications of dual-layer polymeric membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 562, 85–111. 10.1016/j.memsci.2018.05.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. Y.; Chung T.-S.; Qin J.-J. Polybenzimidazole (PBI) nanofiltration hollow fiber membranes applied in forward osmosis process. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 300, 6–12. 10.1016/j.memsci.2007.05.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chi X. Y.; Zhang P. Y.; Guo X. J.; Xu Z. L. Interforce initiated by magnetic nanoparticles for reducing internal concentration polarization in CTA forward osmosis membrane. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 44852 10.1002/app.44852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. E.; Sun W. G.; Wu Q.; Kong Y. F.; Xu Z. L.; Xu S. J.; Zheng X. P. Effect of cellulose triacetate membrane thickness on forward-osmosis performance and application for spent electroless nickel plating baths. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 45049 10.1002/app.45049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S. S.; Chen S.-S.; Li C.-W.; Nguyen N. C.; Nguyen H. T. A comprehensive review: electrospinning technique for fabrication and surface modification of membranes for water treatment application. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 85495–85514. 10.1039/C6RA14952A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Hsiao B. S. Electrospun nanofiber membranes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2016, 12, 62–81. 10.1016/j.coche.2016.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bui N.-N.; Lind M. L.; Hoek E. M. V.; McCutcheon J. R. Electrospun nanofiber supported thin film composite membranes for engineered osmosis. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 385–386, 10–19. 10.1016/j.memsci.2011.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian M.; Qiu C.; Liao Y.; Chou S.; Wang R. Preparation of polyamide thin film composite forward osmosis membranes using electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) nanofibers as substrates. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 118, 727–736. 10.1016/j.seppur.2013.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L.; McCutcheon J. R. Hydrophilic nylon 6,6 nanofibers supported thin film composite membranes for engineered osmosis. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 457, 162–169. 10.1016/j.memsci.2014.01.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puguan J. M. C.; Kim H.-S.; Lee K.-J.; Kim H. Low internal concentration polarization in forward osmosis membranes with hydrophilic crosslinked PVA nanofibers as porous support layer. Desalination 2014, 336, 24–31. 10.1016/j.desal.2013.12.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chi X.-Y.; Zhang P.-Y.; Guo X.-J.; Xu Z.-L. A novel TFC forward osmosis (FO) membrane supported by polyimide (PI) microporous nanofiber membrane. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 427, 1–9. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.07.259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L.; McCutcheon J. R. Impact of support layer pore size on performance of thin film composite membranes for forward osmosis. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 483, 25–33. 10.1016/j.memsci.2015.01.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obaid M.; Mohamed H. O.; Yasin A. S.; Fadali O. A.; Khalil K. A.; Kim T.; Barakat N. A. M. A novel strategy for enhancing the electrospun PVDF support layer of thin-film composite forward osmosis membranes. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 102762 10.1039/C6RA18153H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.-H.; Kwon S. J.; Shin M. G.; Park M. S.; Lee J. S.; Park C. H.; Park H.; Lee J.-H. Polyethylene-supported high performance reverse osmosis membranes with enhanced mechanical and chemical durability. Desalination 2018, 436, 28–38. 10.1016/j.desal.2018.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.; Wang S.; Zhao P.; Liang H.; Zhang W.; Crittenden J. High-performance polyamide thin-film composite nanofiltration membrane: Role of thermal treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 435, 415–423. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.11.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.-J.; Wang L.-J.; Xu Z.-L.; Zhang H.-Z. Novel chitosan-piperazine composite nanofiltration membranes for the desalination of brackish water and seawater. J. Polym. Res. 2018, 25, 118 10.1007/s10965-018-1514-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osman Z.; Arof A. K. FTIR studies of chitosan acetate based polymer electrolytes. Electrochim. Acta 2003, 48, 993–999. 10.1016/S0013-4686(02)00812-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Peh M. H.; Thong Z.; Chung T.-S. Thin Film Interfacial Cross-Linking Approach To Fabricate a Chitosan Rejecting Layer over Poly(ether sulfone) Support for Heavy Metal Removal. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 472–479. 10.1021/ie503809c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Zhang J.; Jiang Q.; Xia W. Physicochemical and structural characteristics of chitosan nanopowders prepared by ultrafine milling. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 309–313. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C. Y.; Kwon Y.-N.; Leckie J. O. Effect of membrane chemistry and coating layer on physiochemical properties of thin film composite polyamide RO and NF membranes: I. FTIR and XPS characterization of polyamide and coating layer chemistry. Desalination 2009, 242, 149–167. 10.1016/j.desal.2008.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akin O.; Temelli F. Probing the hydrophobicity of commercial reverse osmosis membranes produced by interfacial polymerization using contact angle, XPS, FTIR, FE-SEM and AFM. Desalination 2011, 278, 387–396. 10.1016/j.desal.2011.05.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obaid M.; Ghouri Z. K.; Fadali O. A.; Khalil K. A.; Almajid A. A.; Barakat N. A. Amorphous SiO2 NP-Incorporated Poly(vinylidene fluoride) Electrospun Nanofiber Membrane for High Flux Forward Osmosis Desalination. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 4561–4574. 10.1021/acsami.5b09945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y. C.; Chi X. Y.; Xu Z. L.; Guo X. J. Morphological controlling of CTA forward osmosis membrane using different solvent-nonsolvent compositions in first coagulation bath. J. Polym. Res. 2017, 24, 156 10.1007/s10965-017-1311-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Li L.; Wei Y.; Xue J.; Chen H.; Ding L.; Caro J.; Wang H. Water Transport with Ultralow Friction through Partially Exfoliated g-C3 N4 Nanosheet Membranes with Self-Supporting Spacers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 8974–8980. 10.1002/anie.201701288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo H.-R.; Cao G.-P.; Wang M.; Zhang H.-H.; Song C.-C.; Fang X.; Wang T. Controlling the morphology and performance of FO membrane via adjusting the atmosphere humidity during casting procedure. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 433, 945–956. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.08.158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sablani S. S.; Goosen M. F. A.; Al-Belushi R.; Wilf M. Concentration polarization in ultrafiltration and reverse osmosis: a critical review. Desalination 2001, 141, 269–289. 10.1016/S0011-9164(01)85005-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon J. R.; Elimelech M. Influence of concentrative and dilutive internal concentration polarization on flux behavior in forward osmosis. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 284, 237–247. 10.1016/j.memsci.2006.07.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bian L.; Fang Y.; Wang X. Experimental investigation into the transmembrane electrical potential of the forward osmosis membrane process in electrolyte solutions. Membranes 2014, 4, 275–286. 10.3390/membranes4020275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian L.; Fang Y.; Wang X. Water and solute transport phenomena in forward osmosis process. CIESC J. 2014, 65, 2813–2820. 10.3969/j.issn.0438-1157.2014.07.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C.; Ma P.; Zhu C.; Chen M. Measurement and correlation on diffusion coefficients of aqueous glucose solutions. CIESC J. 2005, 56, 1–5. 10.3969/j.issn.0438-1157.2014.07.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H.; Matsumura M.; Veliky I. A. Diffusion characteristics of substrates in Ca-alginate gel beads. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1984, 26, 53–58. 10.1002/bit.260260111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace M.; Cui Z.; Hankins N. P. A thermodynamic benchmark for assessing an emergency drinking water device based on forward osmosis. Desalination 2008, 227, 34–45. 10.1016/j.desal.2007.04.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Achilli A.; Cath T. Y.; Childress A. E. Selection of inorganic-based draw solutions for forward osmosis applications. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 364, 233–241. 10.1016/j.memsci.2010.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Xu J.; Lu J.; Shan B.; Gao C. Enhanced performance of cellulose triacetate membranes using binary mixed additives for forward osmosis desalination. Desalination 2017, 405, 68–75. 10.1016/j.desal.2016.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X.; Liu Z.; Hua M.; Kang T.; Li X.; Zhang Y. Poly(ethylene glycol) crosslinked sulfonated polysulfone composite membranes for forward osmosis. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 43941 10.1002/app.43941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li G.; Wang J.; Hou D.; Bai Y.; Liu H. Fabrication and performance of PET mesh enhanced cellulose acetate membranes for forward osmosis. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 45, 7–17. 10.1016/j.jes.2015.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G.; Li X.-M.; He T.; Jiang B.; Gao C. Cellulose triacetate forward osmosis membranes: preparation and characterization. Desalin. Water Treat. 2013, 51, 2656–2665. 10.1080/19443994.2012.749246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bui N. N.; McCutcheon J. R. Hydrophilic nanofibers as new supports for thin film composite membranes for engineered osmosis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 1761–1769. 10.1021/es304215g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui N.-N.; McCutcheon J. R. Nanoparticle-embedded nanofibers in highly permselective thin-film nanocomposite membranes for forward osmosis. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 518, 338–346. 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.06.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.; Wang X.; Wang Y. Design of Carbon Black/Polypyrrole Composite Hollow Nanospheres and Performance Evaluation as Electrode Materials for Supercapacitors. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1795–1801. 10.1021/sc5001034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo R.; Calabrese I.; Gelardi G.; Turco Liveri M. L.; Pojman J. A. The apparently anomalous effects of surfactants on interfacial tension in the IBA/water system near its upper critical solution temperature. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2016, 294, 1425–1430. 10.1007/s00396-016-3904-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klaysom C.; Hermans S.; Gahlaut A.; Van Craenenbroeck S.; Vankelecom I. F. J. Polyamide/Polyacrylonitrile (PA/PAN) thin film composite osmosis membranes: Film optimization, characterization and performance evaluation. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 445, 25–33. 10.1016/j.memsci.2013.05.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb S.; Titelman L.; Korngold E.; Freiman J. Effect of porous support fabric on osmosis through a Loeb-Sourirajan type asymmetric membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 1997, 129, 243–249. 10.1016/S0376-7388(96)00354-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cath T.; Childress A.; Elimelech M. Forward osmosis: Principles, applications, and recent developments. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 281, 70–87. 10.1016/j.memsci.2006.05.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Huang M.-L.; Cao Y.; Ma X.-H.; Xu Z.-L. Fabrication, characterization and separation properties of three-channel stainless steel hollow fiber membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 515, 144–153. 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.05.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q.; Chung T.-S.; Santoso Y. E. Tailoring pore size and pore size distribution of kidney dialysis hollow fiber membranes via dual-bath coagulation approach. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 290, 153–163. 10.1016/j.memsci.2006.12.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]