Abstract

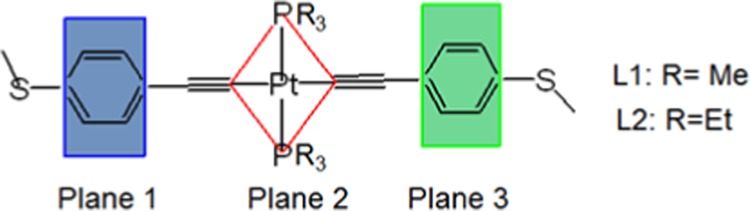

Two organometallic ligands L1 (trans-[p-MeSC6H4C≡C-Pt(PR3)2-C≡CC6H4SMe; R = Me]) and L2 (R = Et) react with CuX salts (X = Cl, Br, I) in MeCN to form one-dimensional (1D) or two-dimensional (2D) coordination polymers (CPs). The clusters formed with copper halide can either be step cubane Cu4I4, rhomboids Cu2X2, or simply CuI. The formed CPs with L1, which is less sterically demanding than L2, exhibit a crystallization solvent molecule (MeCN), whereas those formed with L2 do not incorporate MeCN molecules in the lattice. These CPs were characterized by X-ray crystallography, thermogravimetric analysis, IR, Raman, absorption, and emission spectra as well as photophysical measurements in the presence and absence of crystallization MeCN molecules for those CPs with the solvent in the lattice (i.e., [(Cu4I4)L1·MeCN]n (CP1), [(Cu2Br2)L1·2MeCN]n (CP3), and [(Cu2Cl2)L1·MeCN]n (CP5)). The crystallization molecules were removed under vacuum to evaluate the porosity of the materials by Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (N2 at 77 K). The 2D CP shows a reversible type 1 adsorption isotherm for both CO2 and N2, indicative of microporosity, whereas the 1D CPs do not capture more solvent molecules or CO2.

Introduction

The use of organometallic ligands for the synthesis of coordination polymers1 (CPs) and metal-organometallic frameworks (MOFs), mostly aimed at catalytic purposes,2 has been the topic of a relatively recent interest. In parallel, the incorporation of S-containing moieties into organometallic fragments has been a long-standing approach in ligand design,3 and sulfur-containing organics are also well known to assemble Cu(I)-containing species to form one-dimensional (1D), two-dimensional (2D), and three-dimensional coordination polymers.4 Concurrently, the use of the rigid and readily modulable trans-bisacetynylplatinum(II) synthon −C6H4C≡C–Pt(PR3)2–C≡CC6H4– (R = simple alkyls or aryls) [Pt] for the preparation of organometallic polymers has been thoroughly investigated in the past decades, mostly to shine light on their photonic and electrochemical properties and to design light-harvesting and light-emitting devices.5−9 The approach of anchoring of a S-containing residue onto a [Pt] scaffold has been recently performed and used to prepare 2D networks containing Ag nanoparticles.10 The strategy in this case was to generate the corresponding dithiolates,11 which exhibit a different affinity with metals in comparison to the softer thioethers. These materials were not designed for their ability to capture small molecules like MOFs but rather to exploit their assembling ability10 and electronic conductivity.11

In a recent study on 1D and 2D coordination polymers generated by luminescent CuI clusters and flexible RC6H4S(CH2)8SC6H4R (R = t-Bu, Me, respectively) dithioethers, the presence of macrocycles within their framework has been revealed.12 Despite their low porosity, these materials exhibit the reversible removal of small molecules, such as nitriles, MeOH, and CO2, suggesting that they somewhat act like MOFs. However, the major challenge for these materials is that the combination of mono- and dithioethers with CuX salts (X = Cl, Br, I, CN) stubbornly leads to a complete unpredictability of the outcome of the Cu cluster acting as the node and the dimensionality of the coordination polymer.4

We now report the design of two series of coordination polymers prepared from CuX salts (X = Cl, Br, I) and trans-MeSC6H4C≡C-Pt(PR3)2-C≡CC6H4SMe (R = Me (L1), Et (L2)) in MeCN, where two trends are observed. First, the dimensionality of the resulting polymers is not affected whether R = Me or Et. Second, the polymers formed with L1 reveal the presence of crystallization MeCN molecules in the lattice, whereas those formed with L2 do not, despite the identical nature of some of these materials (notably [(Cu2X2)L1]n and [(Cu2X2)L2]n; X = Cl, Br).

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Structure Description

L1 and L2 differ only by their R group, Me versus Et. On the basis of past experience, such a subtle difference usually leads to a major variability in nature of the copper(I) cluster (often referred to as secondary building unit; SBU) and polymer dimensionality when flexible chains are used in the thioether ligands.4a−4c,19 This is not the case for the rigid L1 and L2 with CuX (X = Cl, Br), which lead in all four cases to 1D polymers CP3–CP6 (Scheme 1, Tables 1 and 2, and Figure 1). These materials belong to a category of coordination polymers previously reported for the trans-bis(phenylacetylnyl)bis(triphenylphosphine)platinum(II) complex, where rhomboid-type SBUs are anchored via a η2–C≡C coordination bonds (Cu2Br2 and Ag2(CF3SO3)2).13,14,15 During the course of this study, the X-ray structure of L2 was obtained (SI) and is found to be consistent with that in the literature,7j,16 without any further description.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of L1, L2, and CP1–CP6 in MeCN.

(i) cis-PtCl2(PMe3)2 (L1) and trans-PtCl2(PEt3)2 (L2), NHEt2, CuI, tetrahydrofuran.

Table 1. Comparison of Selected Structural Features of CP1–CP6.

| CP1 | CP2 | CP3 | CP4 | CP5 | CP6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBU structure | Cu4I4 | CuI | Cu2Br2 | Cu2Br2 | Cu2Cl2 | Cu2Cl2 |

| CP dimensionality | 2D | 1D | 1D | 1D | 1D | 1D |

| crystallization mol./[Pt] | MeCN | 2 (MeCN) | MeCN | |||

| nb of trivalent Cu | 2/2 | 2/0 | 2/0 | 2/0 | 2/0 | 2/0 |

| nb of tetravalent Cu | ||||||

| nb of Cu–S bonds | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| nb of Cu–X bonds | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| nb of Cu–(η2–C≡C) bonds | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Table 2. Bond Distances in the Rhomboid Cu2X2 Units in CP3–CP6.

|

CP3 |

CP4 |

CP5 |

CP6 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bond | (Å) | bond | (Å) | bond | (Å) | bond | (Å) |

| Cu1–Cu2 | 3.190(5) | Cu1–Br1#2 | 2.411(4) | Cu1–Cu1 | 3.0898(6) | Cu2–Cu2 | 3.146(1) |

| Cu1–Br1 | 2.423(5) | Cu1–Br1 | 2.462(3) | Cu1–Cl1 | 2.3070(9) | Cl3–Cu2#2 | 2.2806(1) |

| Cu1–Br2 | 2.401(5) | Cu1–Cu1 | 3.289(1) | Cl1–Cu1 | 2.2878(8) | Cl3–Cu2 | 2.3302(1) |

| Cu2–Br2 | 2.418(5) | Cl1–Cl1 | 3.401(1) | Cl3–Cl3 | 3.371(1) | ||

| Cu2–Br1 | 2.407(5) | ||||||

| Br1–Br2 | 3.619(4) | ||||||

Figure 1.

Oak ridge thermal ellipsoid plot (ORTEP) representations of a fragment of the 1D polymers CP3 (top left), CP4 (top right), CP5 (bottom left), and CP6 (bottom right). The thermal ellipsoids are set at 50% probability. Yellow = S, pale purple = Pt, orange = P, brown = Cu, dark red = Br, green = Cl, blue = C, white = H, and purple = N.

Conclusively, there is a clear selectivity favoring the ethynyl unit over the thioether by the Cu(I) cation. Moreover, L1 bears smaller PMe3 groups comparatively to PEt3 and so the voids left by the former group are compensated by MeCN crystallization molecules. This trend where L1 uses MeCN to occupy the empty spaces is also noted for CuI salt (i.e., no MeCN in the lattice of CP2; Figure 2, Table 3). However, two drastic differences are noted. First, the dimensionality is 2D for both CPs via the use of S–Cu coordinations. Second, the SBUs used by CP1 and CP2 also differ. The former uses the known step cubane SBU, and the latter material assembles through a mononuclear Cu–I complex. To the best of our knowledge, the use of a single Cu–I SBU is unprecedented in the formation of CPs built upon thioethers and CuX salts (X = Cl, Br, I, CN).4a−4c

Figure 2.

Top: (a) ORTEP representation of a fragment of CP1. The thermal ellipsoids are set at 50% probability. Yellow = S, purple = Pt, brown = Cu, orange = P, green = I, blue = C, and white = H. Only one MeCN molecule is shown inside a cavity. (b) View of the Cu4I4 step-like cluster. (c) Extended fragment of CP1. Yellow = S, purple = I, brown = Cu, orange = P, gray = C, and silver = Pt. Bottom: ORTEP representation of a fragment of CP2. The thermal ellipsoids are set at 50% probability. Yellow = S, pale purple = Pt, orange = P or Cu when attached to two I, green = I, dark purple = N, blue = C, and white = H.

Table 3. Selected Bond Distances for CP1 and CP2 (See Figure 2).

|

CP1 |

CP2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| bond | (Å) | bond | (Å) |

| Cu1–Cu1 | 2.8416(9) | Cu1–I1 | 2.544(2) |

| Cu2–Cu1 | 2.8736(8) | Cu2–I2 | 2.550(2) |

| Cu1–I1 | 2.6274(6) | Cu1–S1 | 2.294(4) |

| Cu1–I2 | 2.6409(9) | Cu2–S2 | 2.307(4) |

| Cu2–I1 | 2.5742(6) | ||

| I2–I2 | 4.1903(7) | ||

| I2–I2 | 4.4712(8) | ||

| Cu1–S1 | 2.335(1) | ||

One interesting structural feature is the significant distortion that L1 and L2 experience upon coordination. Indeed, the most notable structural deviations from an ideal geometry are the C–C≡C angles. In L1 and L2, these angles are only within 4° from the linearity, but fall in the range of approximately 153–169° in CP1–CP6 (Tables 4 and 5). These distortions are also noted in the interplanar C6H4···C6H4 distances. In L1, this distance is 0.88 Å but increases to distances varying from 1.48 to 3.19 Å for CP1 and CP4–CP6. In case of L2, CP2, and CP3, the C6H4 planes of the ligands form dihedral angles with each other.

Table 4. Interplanar C6H4···C6H4 Distances and C–C≡C Angles within L1 and L2.

| L1 | L2 | CP1 | CP2 | CP3 | CP4 | CP5 | CP6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D (planes 1 and 3) (Å) | 0.881 | a | 2.283 | a | a | 3.122 | 1.484 | 3.190 |

| C–C≡C angle (deg) | 176.1 | 176.6 | 159.8 | 169.1 | 161.0 | 155.0 | 163.5 | 155.2 |

| 177.2 | 152.8 | 165.5 |

Not measured as the planes are not parallel.

Table 5. Measured Angles between Planes 1, 2, and 3a.

| planes | L1 (deg) | L2 (deg) | CP1 (deg) | CP2 (deg) | CP3 (deg) | CP4 (deg) | CP5 (deg) | CP6 (deg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 and 2 | 30.22 | 72.88 | 42.64 | 38.65 | 37.27 | 88.47 | 41.74 | 89.67 |

| 2 and 3 | 30.22 | 70.42 | 42.64 | 39.33 | 40.24 | 88.48 | 41.74 | 89.67 |

| 1 and 3 | a | 2.68 | a | 3.65 | 3.89 | a | a | a |

Not measured as the planes 1 and 3 are parallel.

Thermal Stability

The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) trace of L2 is used as comparison (see SI for traces and data). It exhibits two major weight losses near 260 and 435 °C most likely corresponding to the loss of one PEt3 (exp. ∼15%, calcd = 16%) and one C≡CC6H4SMe (exp. ∼ 26%, calcd = 21%), respectively. These two plateaus represent a “fingerprint” observed in all of the coordination polymers investigated. Neither L1 nor L2 exhibit crystallization molecules based on their X-ray structures and so no weight loss associated with solvent losses is observed (i.e., at lower temperature).

Conversely, the presence of MeCN molecules is evident from the weight losses depicted in the TGA traces for CP1 and CP3 in the vicinity of 100 °C (Figure 3, see SI for data). The expected absence of MeCN in the lattice of CP2, CP4, and CP6 is also obvious by the lack of weight loss in the 25–200 °C window. In addition, the effect of ν(C≡C) in the two ligands (L1 and L2) on the formation of CPs was monitored using IR and Raman (for L1, CP1, CP3, and CP5) spectroscopy measurements. These values for the IR data are observed to be in the range of ∼2108 cm–1 for L2CP1–CP6, whereas it was confirmed that the Raman values for L1, CP1, CP3, and CP5 also fall in relatively the same range of ∼2108 cm–1 (see SI).

Figure 3.

Top: Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns of CP1; black = calculated from the single-crystal X-ray data, blue = measured from (crushed) single crystals, and red = after removing the MeCN crystallization molecule under vacuum. Bottom: CO2 (red; at 273 K) and N2 (black; at 77 K) sorption isotherms for CP1, measured from single crystals. Closed circles = adsorption; open circles = desorption.

Surprisingly, CP5 does not show any weight loss associated with the crystallization molecule. This is due to the crystal “instability” of the latter, which exhibit quick evaporation of the solvent crystallization molecules. The X-ray structure was obtained by selecting a suitable crystal in the mother liquor and then dipping it in glue to avoid solvent evaporation. For TGA analysis, the use of glue is obviously impossible and the solvent is completely gone after about 1 day. Prior to discussing the particularity of CP3 and CP5, the gas sorption of CP1 is presented.

Gas Sorption Measurements and Solvent Removal of MeCN in CP1

Gas sorption isotherms (CO2 and N2) of CP1 at low pressure ranging between 0 and 1100 mbar (∼1.1 atm) were measured (Figure 4, bottom). The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) data reveal that CP1 is weakly porous (Tables 5 and 6; a space-filling model of the X-ray structure is given in the SI). The CO2 sorption at 273 K and N2 sorption at 77 K exhibit type 1 isotherms, which again corroborate the presence of microporous materials. Moreover, despite the low surface area of 79.5 m2/g for CP1 upon removal of MeCN, this microporous material is still able to adsorb up to 16.8 cm3/g STP of CO2 at ∼1.1 bar.

Figure 4.

TGA traces focusing on the temperature range where the solvent loss occurs in CP1 (i.e., MeCN) as synthesized, showing solvent loss. Black: CP1 and CP3 were used as single crystals; red: TGA curve after the solvent removal under vacuum; blue: TGA trace after exposition to MeCN vapor. Full TGA traces are provided in the SI. For CP5, the MeCN solvent evaporated too quickly to be observed. The TGA trace is the same as that for the blue and red traces of CP3. We note that CP5 does not exhibit a plateau in this range.

Table 6. Gas Adsorption Data for CP1, CP3, and CP5a.

| gas | T (K) | P (mbar) | quantity adsorbed (cm3/g STP) | surface area (m2/g) | pore volume (cm3/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP1 | CO2 | 273 | 1046 | 16.8 | 79.5 | 0.027 |

| N2 | 77 | 972 | 2.6 | 2.3 | <0.01 | |

| CP3 | CO2 | 273 | 1046 | 1.9 | 0.5 | <0.01 |

| N2 | 77 | 1001 | b | c | c | |

| CP5 | CO2 | 273 | 1046 | 1.8 | 1.3 | <0.01 |

| N2 | 77 | 994 | 0.7 | 0.4 | <0.01 |

For CO2, estimation of the structural parameters was made using density functional theory (DFT) calculations model, whereas for N2 gas, the surface area was measured from BET.

Too small to be estimated.

Not calculated.

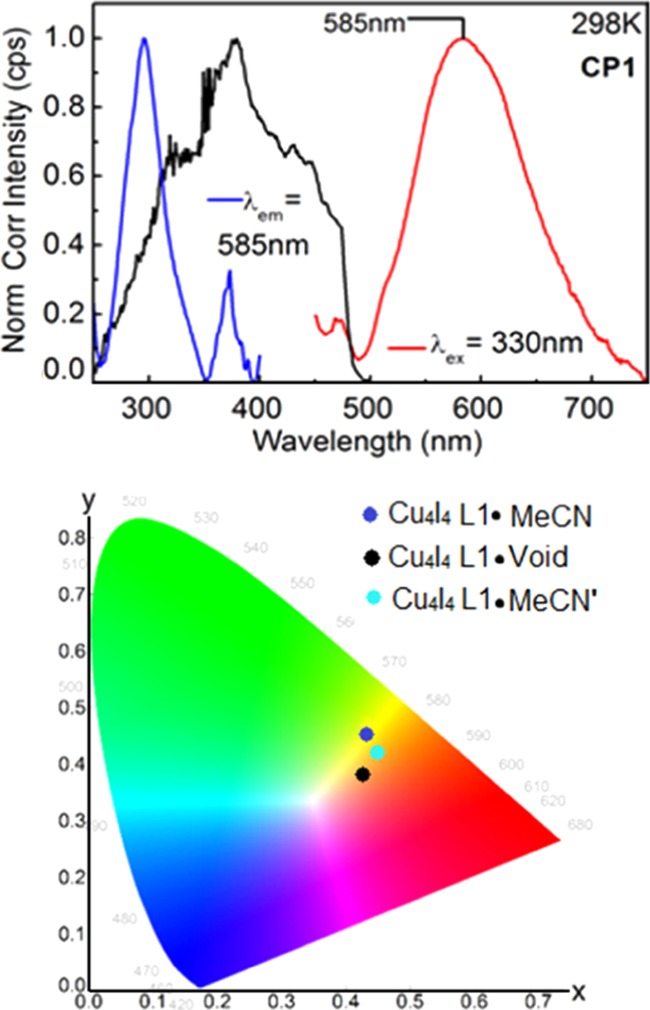

The powder XRD pattern of CP1 directly measured from the resulting solid after the synthesis exhibits a close similarity with the calculated one using X-ray data extracted from the single crystal, thus confirming its identity. Upon removing the solvent under vacuum (as monitored by TGA, Figure 4), the resulting powder XRD pattern exhibits only modest modifications (at 2θ ≈ 10 and 42°, Figure 4), indicating that the polymer structure is intact. More importantly, the peak positions (i.e., 2θ values) remain unaffected within 0.2° upon removing the MeCN. This result indicates that the 2D grid is rather rigid. The reversible removal and reintroduction of the MeCN molecules in the framework of CP1 was also monitored using the chromaticity measurements as it is conveniently found emissive at 298 K (Figure 5). The chromaticity data undergo a slight change upon removing the crystallization molecule (from the purple dot to the black dot).

Figure 5.

Top: Absorption (black), excitation (blue), and emission (red) spectra of CP1. Bottom: Chromaticity diagram of CP1 before (0.43270, 0.44875) and after removing MeCN (0.42015, 0.38006) and after reintroducing it from vapor (0.44754, 0.42595).

As shown, the emission spectrum of CP1 is observed to have a featureless broad band with maximum at 585 nm at room temperature. This feature in these CPs has been previously reported by our group and found to originate from the triplet state due to a large Stokes shift between the absorption maximum with the emission peak. In addition, on the basis of the previous DFT and time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) calculations, the nature of the excited states for CP1 originates from both intra-L1 (intra-ligand ππ* mixed with MLCT; M = Pt, L = π*–C≡CC6H4) and MXLCT (metal-to-ligand charge transfer, Cu4I4 →L1; MX = Cu4I4; L = L1).17a,17b

Upon partial reintroduction of the solvent (∼33% based on TGA data in Figure 4), the chromaticity data expectedly exhibit again a slight modification moving almost in the direction toward its original position in the chromaticity diagram (from the black dot to the turquoise dot) in Figure 5. Thus, CP1 is capable of releasing MeCN (and CO2), but the uptake is difficult (i.e., slow). Even though the uptake is lower than that in many microporous materials, type I adsorption isotherm is observed.

Special Cases of CP3 and CP5

Both materials exhibit MeCN crystallization molecules in their lattices (Figure 1), but TGA analyses indicate that there is no readsorption of the solvent after removal for CP3 (Figure 4, right) and not at all for CP5 when the single crystals are exposed to air for a certain time (SI).

In an attempt to figure out this particular result, CP3 was subjected to necessary crushing for powder XRD analysis, and the resulting pattern turned out to be completely different from the calculated pattern extracted from its X-ray data (Figure 6). This experiment indicates that CP3 has changed during crushing, a resulting structure exhibiting no crystallization molecules based on the TGA traces (Figures 4). In an attempt to figure out whether this mechanical stress induces only an evaporation of the solvent without altering the 1D structure of the polymer (as this was the case for CP1) (Figure 3), the experimental powder XRD traces of CP3 were compared to the calculated ones of CP4 and CP6 (Figure 7, bottom), two polymers for which no crystallization molecules exist in the lattice even though L2 was used for the synthesis of latter CPs.

Figure 6.

Powder XRD patterns upon crushing single crystals (blue), calculated (black), after MeCN removal (red), and recovered from MeCN (green) for CP3 (CP5 is provided in the SI).

Figure 7.

Powder XRD patterns upon crushing the single crystals (blue) and calculated (black) for CP2, CP4, and CP6.

The attempt was unsuccessful as there is no resemblance. The conclusion is that CP3 and CP5 are unstable with time, temperature, and vacuum conditions as they lose the solvent meaning these are kinetic products becoming thermodynamic ones because the solvent does not reenter their lattice. Moreover, when these materials are subjected to increased pressure from crushing, there is an irreversible change of structure (i.e., new thermodynamic product). The latter process could be the result of a combination of both losing the solvent and leaving space for reorganization of the structure. Because the structures of CP3 and CP5 are unknown after subjecting them to these conditions, this possible explanation is still speculative.

Crystal Transformation of CP3 and CP5

To determine whether there is transformation for CP3 and CP5, powder of CP3 after MeCN removal was redissolved in MeCN and prismlike crystals similar to those obtained after synthesis were formed. However, the powder XRD measurements confirmed that the pattern of the recovered crystals from the initial powder is not identical to the calculated PXRD pattern. These crystals were only verified by PXRD, which indicated that the molecule is not identical (Figure 6, green line).

Therefore, this speculation of the crystal transformation for CP3 and CP5 upon solvent removal is assumed to be correct because the obtained single crystals after redissolving in MeCN showed also different PXRD patterns from any previous ones (Figure 6).

On the other hand, PXRD patterns for CP2, CP4, and CP6 as synthesized were compared to the calculated PXRD patterns and found to be identical (Figure 7). This clearly indicates that CP2, CP4, and CP6 do not undergo any crystal transformation upon crushing. In addition, the fact that these do not incorporate the solvent in the cavity means that they do not collapse. Therefore, we can conclude that the 1D CPs (CP3 and CP5) with MeCN in the voids will not hold the solvent for long as the acetonitrile seems to evaporate upon crushing the crystals.

Conclusions

Ligand design going from L1 to L2 (i.e., PMe3 to PEt3) permitted to generate 1D coordination polymers without any crystallization solvent trapped in the voids. The predictability comes in effect due to the length of alkyl chain on the PEt3 of L2 as compared to L1, which has PMe3. Even though CP3–CP6 are identical as they are all coordinated in the same fashion and are 1D CPs, CP3 and CP5 show crystallization molecules (MeCN in their voids), whereas CP4 and CP6 have no crystallization molecule. This is so because of the crystallization molecules which will occupy the voids available for the polymers made with L1 as there is a short alkyl chain (i.e., PMe3), whereas for the polymers made from L2, no solvent occupies the voids due to steric hindrance of the alkyl chain (i.e., PEt3) and thus resulting in more compact lattice as there is no space available for the solvent to be trapped in. This phenomenon is illustrated by the formation of a 2D CP1 when L1 is used, and MeCN is seen trapped in the cavity when L2 forms a 1D CP2 and the cluster step cubane SBU has broken.

Experimental Section

Materials

CuI, CuBr, CuCl, and trans- and cis-dichlorobis(trimethylphosphine)platinum(II), were purchased from Aldrich. L1 was prepared as previously reported by our group,17a whereas L2 (see SI) was prepared according to a standard procedure outlined as L1 above and as reported in the literature11b,11c,13 using 4-ethynylthioanisole, which was synthesized as previously reported.17a,18

Synthesis of [(Cu4I4)L1·MeCN]n (CP1)

Acetonitrile (5 mL) was bubbled under argon for 20 min. L1 (50 mg, 0.078 mmol) was added, followed by CuI (29.7 mg, 0.16 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The mixture was slightly heated and then allowed to cool at room temperature, thus forming crystals. The solvent was removed and dried under vacuum. Anal. Calcd for C14H19Cu2I2NPPt0.50S (742.76): C, 19.99; H, 2.26; N, 1.67%. Found: C, 20.82; H, 2.47; N, 1.52%. IR (cm–1): 2966, ν(CH); 2876, ν(CH); 2108, ν(C≡C); 1647, ν(C=C).

Synthesis of [(Cu2I2)L2]n (CP2)

Acetonitrile (5 mL) was bubbled under argon for 20 min. L2 (30.0 mg, 0.041 mmol) was added, followed by CuI (15.6 mg, 0.082 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The mixture was slightly heated and allowed to cool at room temperature, which facilitates crystal formation. The solvent was removed and dried under vacuum for 1 day. Anal. Calcd for C30H44Cu2I2P2PtS2 (1106.68): C, 32.52; H, 3.98%. Found: C, 32.48; H, 4.42%. IR (cm–1): 2971, ν(CH); 2868, ν(CH); 2107, ν(C≡C); 1663, ν(C=C).

Synthesis of [(Cu2Br2)L1·2MeCN]n (CP3)

Acetonitrile (5 mL) was bubbled under argon for 20 min. L1 (50.0 mg, 0.078 mmol) was added, followed by CuBr (22 mg, 0.16 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The mixture was slightly heated and allowed to cool at room temperature, facilitating crystal formation. Anal. Calcd for C28H38Br2Cu2N2P2PtS2 (1010.65): C, 33.24; H, 3.76; N, 2.77%. Found: C, 31.89; H, 3.63; N, 0.25%. The found elemental analysis in this case is lower due to suspected desolvation of the CP. IR (cm–1): 2968, ν(CH); 2889, ν(CH); 2109, ν(C≡C); 1650, ν(C=C).

Synthesis of [(Cu2Br2)L2]n (CP4)

Acetonitrile (5 mL) was bubbled under argon for 20 min. L2 (30.0 mg, 0.041 mmol) was added, followed by CuBr (11.8 mg, 0.082 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The mixture was slightly heated and allowed to cool at room temperature, facilitating crystal formation. Anal. Calcd for C30H44Br2Cu2P2PtS2 (1012.70): C, 35.54; H, 4.34%. Found: C, 35.60; H, 4.31%. IR (cm–1): 2970, ν(CH); 2867, ν(CH); 2107, ν(C≡C); 1661, ν(C=C).

Synthesis of [(Cu2Cl2)L1·MeCN]n (CP5)

Acetonitrile (5 mL) was bubbled under argon for 20 min. L1 (40.0 mg, 0.062 mmol) was added, followed by CuCl (12.3 mg, 0.13 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The mixture was slightly heated and allowed to cool at room temperature, facilitating crystal formation. Anal. Calcd for C28H38Cl2Cu2N2P2PtS2 (921.78 C, 36.45; H, 4.12; N, 3.04%. Found: C, 32.73; H, 3.72; N, 0.49%). The found elemental analysis in this case is lower due to suspected desolvation of the CP. IR (cm–1): 2978, ν(CH); 2887, ν(CH); 2110, ν(C≡C); 1645, ν(C=C).

Synthesis of [(Cu2Cl2)L2]n (CP6)

Acetonitrile (5 mL) was bubbled under argon for 20 min. L2 (20.0 mg, 0.050 mmol) was added, followed by CuCl (8.9 mg, 0.10 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The mixture was slightly heated and allowed to cool at room temperature, facilitating crystal formation. Anal. Calcd for C30H44Cl2Cu2P2PtS2 (923.78): C, 38.96; H, 4.76%. Found: C, 38.83; H, 4.67%. IR (cm–1): 2970, ν(CH); 2868, ν(CH); 2108, ν(C≡C); 1669, ν(C=C).

Gas Sorption Isotherm Measurements

Gas sorption isotherms were measured using Micromeritics instrument “Accelerated Surface Area and Porosimetry” (ASAP 2020) analyzer at low pressure ranging between 0 and 1100 mbar (∼1.1 bar). Warm and cold free space correction measurements were performed for the isotherms using ultrahigh-purity He gas with purity of 99.999%. The other gases used are of high grade with purities of 99.999 and 99.99% for N2 and CO2 gases, respectively. The measurements were performed at 77 K for N2 gas, whereas for CO2 gas, the measurements were performed at 273 K. Before performing the sorption measurements, the samples were heated under reduced pressure of 600 mbar at 110 °C for approximately 6 h and their mass was measured. Then, the samples were backfilled with N2 and transported to the analysis port where further evacuation was done for 2 h before starting the whole analysis. The surface area and pore volumes were calculated by Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET)19,20b,21 and density functional theory (DFT)20 models for N2 and CO2, respectively.

Important notice. Single crystals were grown from evaporation of acetonitrile solutions. For analyses, such as BET and TGA, the crystals were carefully selected from the dried sample under a microscope. For powder diffraction and luminescence analyses, these crystals were then crushed using a mortar to introduce the powder inside the capillaries.

Instruments

Solid-state UV−vis were recorded using a Varian Cary 50 spectrophotometer at 298 K with a grazing-angle transmittance apparatus having a homemade 77 K sample holder. Steady-state fluorescence and excitation spectra were measured on an Edinburgh Instruments FL980 phosphorimeter equipped with single monochromators. All samples were fished out as single crystals under the microscope and were crushed prior to use. The steady-state fluorescence spectra were recorded using a capillary. These spectra were corrected for instrument response. The Edinburgh Instruments FL980 phosphorimeter is equipped with a “flash” pulsed lamp. The repetition rate of the pulse can be adjusted from 1 to 100 Hz. The instrument was also used to measure the chromaticity. The TGA traces were acquired on a PerkinElmer TGA 7 apparatus in the temperature range of 20−900 °C at 10 °C/ min under an argon atmosphere. The figures were treated by Origin software.

X-ray Crystallography

A clear pale yellow prismlike single crystal of L2 was measured on a Bruker Apex DUO system equipped with a Cu Kα ImuS microfocus source with MX optics (λ = 1.54186 Å). Clear light yellow prismlike single crystals of CP1, CP3, and CP6; a clear intense yellow prismlike single crystal of CP2, a clear pale orange prismlike single crystal of CP4, and a clear light orange prismlike single crystal of CP5 were measured on a Bruker Kappa APEX II DUO CCD system equipped with a TRIUMPH curved crystal monochromator and a Mo fine-focus tube (λ = 0.71073 Å). Diffraction data were recorded at 173 K for L2, CP1, CP2, CP3, CP4, CP5, and CP6. A total of 797 frames were collected for L2, CP1, CP2, CP3, CP4, CP5, and CP6. The frames were integrated with the Bruker SAINT22 software package using a narrow-frame algorithm for all CPs and a wide-frame alogarithm was used for L2. Data were corrected for absorption effects using the multiscan method (SADABS).22 The structures were solved and refined using the Bruker SHELXTL software package using space group P1 with Z = 1 for L2, space group P1̅ with Z = 2 for CP1, space group P1̅, with Z = 1 for CP4, CP5, and CP6, space group P1211 with Z = 2 for CP2, and space group P1 with Z = 1 for CP3. All nonhydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic thermal parameters. The hydrogen atoms were placed in calculated positions and included in final refinement in a riding model with isotropic temperature parameters set to Uiso(H) = 1.5 Ueq(C). Crystal data, data collection, and structure refinement of all compounds are presented in Table S1. Important notice: the crystal structures of CP3 and CP5 undergo a phase change upon crushing. The structure of the resulting materials is not known.

Powder XRD Measurements

Each sample of CP1–CP4 and CP6 were mixed with a small amount of Paratone oil and cut to approximately 0.3 × 0.3 × 0.3 mm3. The samples were placed on a sample holder, which was then mounted on a Bruker APEX DUO X-ray diffractometer at 173 K. A total number of six correlated runs per sample were done with φ scan of 360°. Each sample was then exposed to 270 s on the Cu microfocus anode (1.54184 Å) and the CCD APEX II detector at 150 mm distance. The runs were collected from −12 to −72° 2θ and 6 to 36° ω were treated and integrated with the XRW2 Eval Bruker software to produce WAXD diffraction patterns from 2.5 to 80° 2θ. The patterns were treated with Diffrac.Eva version 2.0 from Bruker.

Procedure for Solvent Removal and Exposure to Solvent Vapor

A small amount of polymers CP1, CP3, and CP5 were inserted in small vials, and the crystallization molecules were removed by heating under reduced pressure (600 mbar) up to 110 °C for 6 h. The removal of the crystallization molecules was confirmed with TGA measurements. The samples treated in this manner were also inserted in small vials, which were then placed in a desiccator containing solvent (MeCN) in a larger recipient. These vials were exposed under reduced pressure (500 mbar) at room temperature for 2 days. For CP1, the reintroduction of the solvent was possible, at least in part, but this was not the case for CP3 and CP5.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Fonds de recherche du Québec-Nature et technologies (FRQNT), and the Centre Quebecois des Materiaux Fonctionnels (CQMF).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.7b01352.

Crystallographic data in CIF format are provided for both L2 and CP1–CP6 (CIF) (CIF) (CIF) (CIF) (CIF) (CIF) (CIF)

Summary of X-ray data collection and refinement of L2 and CP1–CP6, IR spectra of L1, L2, and CP1–CP6. TGA of L2 and CP1–CP6, Raman spectra of L1, CP1, CP3, and CP5. Ball and stick representation of CP2–CP6 and powder XRD of CP5 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Gwengo C.; Iyer R.; Raja M. Rational Design and Synthesis of a New Organometallic Ligand,1-Ferrocenyl-3-(5-bromopyridyl)-prop-3-enol-1-one and Its Heteronuclear Coordination Polymer, {Cu[1-ferrocenyl-3-(5-bromopyridyl)prop-1,3-dionate]2}n. Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 49–53. 10.1021/cg2014573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Wei K.-J.; Ni J.; Liu Y. Heterobimetallic Metal-Complex Assemblies Constructed from the Flexible Arm-Like Ligand 1,1′-Bis[(3-pyridylamino)carbonyl]ferrocene: Structural Versatility in the Solid State. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 1834–1848. 10.1021/ic9021855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yang Y.-Y.; Wong W.-T. A novel 2-D interlinking zigzag-chain d–f mixed-metal coordination polymer generated from an organometallic ligand. Chem. Commun. 2002, 0, 2716–2717. 10.1039/B206823K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kerr A. T.; Kumalah S. A.; Holman K. T.; Butcher R. J.; Cahill C. L. Uranyl Coordination Polymers Incorporating η5-Cyclopentadienyliron-Functionalized η6-Phthalate Metalloligands: Syntheses, Structures and Photophysical Properties. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2014, 24, 128–136. 10.1007/s10904-013-9980-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Müller M.; Hermes S.; Kaehler K.; van den Berg M. W. E.; Muhler M.; Fischer R. A. Loading of MOF-5 with Cu and ZnO Nanoparticles by Gas-Phase Infiltration with Organometallic Precursors: Properties of Cu/ZnO@MOF-5 as Catalyst for Methanol Synthesis. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 4576–4587. 10.1021/cm703339h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Vitillo J. G.; Groppo E.; Bordiga S.; Chavan S.; Ricchiardi G.; Zecchina A. Stability and Reactivity of Grafted Cr(CO)3 Species on MOF Linkers: A Computational Study. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 5439–5448. 10.1021/ic9004664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kumalah S. A.; Holman K. T. Polymorphism and Inclusion Properties of Three-Dimensional Metal-Organometallic Frameworks Derived from a Terephthalate Sandwich Compound. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 6860–6872. 10.1021/ic900816h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Oisaki K.; Li Q.; Furukawa H.; Czaja A. U.; Yaghi O. M. A Metal–Organic Framework with Covalently Bound Organometallic Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 9262–9264. 10.1021/ja103016y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Pullen S.; Fei H.; Orthaber A.; Cohen S. M.; Ott S. Enhanced Photochemical Hydrogen Production by a Molecular Diiron Catalyst Incorporated into a Metal–Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16997–17003. 10.1021/ja407176p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Sesolis H.; Dubarle-Offner J.; Chan C. K. M.; Puig E.; Gontard G.; Winter P.; Cooksy A. L.; Yam V. W. W.; Amouri H. Highly Phosphorescent Crystals of Square-Planar Platinum Complexes with Chiral Organometallic Linkers: Homochiral versus Heterochiral Arrangements, Induced Circular Dichroism, and TD-DFT Calculations. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 8032–8037. 10.1002/chem.201601161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gang Z.; Zhongming W. Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem. 1994, 24, 677–689. 10.1080/00945719408000142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Chung L.-H.; Yeung C.-F.; Ma D.-L.; Leung C.-H.; Wong C.-Y. Metal–Indolizine Zwitterion Complexes as a New Class of Organometallic Material: a Spectroscopic and Theoretical Investigation. Organometallics 2014, 33, 3443–3452. 10.1021/om5003705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Liu H.; Bandeira N. A. G.; Calhorda M. J.; Drew M. G. B.; Felix V.; Novosad J.; de Biani F. F.; Zanello P. J. Organomet. Chem. 2004, 689, 2808–2819. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2004.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Santos I. G.; Hagenbach A.; Abram U. Stable gold (III) complexes with thiosemicarbazone derivatives. Dalton Trans. 2004, 0, 677–682. 10.1039/B312978K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Huang G.; Chen B.; Liu C.; Ma Y.; Liu Y. Transition metal(II) complexes of (E)-cinnamoylferrocene (S)-methylcarbodithioylhydrazone. Transition Met. Chem. 1998, 23, 589–592. 10.1023/A:1006952930584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Jin G.-X.; Herberhold M. The oligoselenide metallacycle complex Cp*Re(NBut) (Se4) as an organometallic ligand. Preparation of the M(CO)5 (M = Cr, Mo, W) adducts [Cp*Re(NBut)(Se4){M(CO)5}2]. Transition Met. Chem. 1998, 23, 529–530. 10.1023/A:1006970915369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Bolinger C. M.; Weatherill T. D.; Rauchfuss T. B.; Rheingold A. L.; Day C. S.; Wilson S. R. (CH3CSH4)2V2S4 as an Organometallic Ligand: Preparation of Iron, Cobalt, Nickel, and Iridium Derivatives and Structures of a V4Ni Cluster and Three V2Fe Clusters. Inorg. Chem. 1986, 25, 634–643. 10.1021/ic00225a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Wilkes S. B.; Bowlas C. J.; Butler I. R.; Underhill A. E. Novel Materials Based on Metallocene-Dithiolenes. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. Sci. Technol., Sect. A 1993, 234, 213–218. 10.1080/10587259308042918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Harvey P. D.; Knorr M. Designs of 3-Dimensional Networks and MOFs Using Mono- and Polymetallic Copper(I) Secondary Building Units and Mono- and Polythioethers: Materials Based on the Cu–S Coordination Bond. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2016, 26, 1174–1197. 10.1007/s10904-016-0378-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Harvey P. D.; Knorr M. Stabilization of (CuX)n Clusters (X = Cl, Br, I; n = 2, 4, 5, 6, 8) in Mono- and Dithioether-Containing Layered Coordination Polymers. J. Cluster Sci. 2015, 26, 411–459. 10.1007/s10876-014-0831-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Harvey P. D.; Knorr M. Luminescent Coordination Polymers Built Upon Cu4X4 (X = Br,I) Clusters and Mono- and Dithioethers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2010, 31, 808–826. 10.1002/marc.200900893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Henline K. M.; Wang C.; Pike R. D.; Ahern J. C.; Sousa B.; Patterson H. H.; Kerr A. T.; Cahill C. L. Structure, Dynamics, and Photophysics in the Copper(I) Iodide–Tetrahydrothiophene System. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 1449–1458. 10.1021/cg500005p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Sina A. A. I.; Al-Rafia S. M. I.; Ahmad M. F.; Paul R. K.; Islam S. M. S.; Younus M.; Raithby P. R.; Ho C.-L.; Lo Y. H.; Liu L.; Wong W.-Y. Synthesis, Structures and Properties of Novel Platinum(II) Acetylide Complexes and Polymers with Tri(tolyl)phosphine as the Auxiliary Ligand. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2015, 25, 427–436. 10.1007/s10904-014-0071-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ho C.-L.; Poon S.-Y.; Lo Pi.-K.; Wong M.-S.; Wong W.-Y. Synthesis, Characterization and Photophysical Properties of Metallopolyynes and Metallodiynes of Platinum(II) with Dibenzothiophene Derivatives. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2013, 23, 206–215. 10.1007/s10904-012-9761-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Wang Q.; He Z.; Wild A.; Wu H.; Cao Y.; Schubert U. S.; Chui C.-H.; Wong W.-Y. Platinum–Acetylide Polymers with Higher Dimensionality for Organic Solar Cells. Chem. – Asian J. 2011, 6, 1766–1777. 10.1002/asia.201100111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Li L.; Chow W.-C.; Wong W.-Y.; Chui C.-H.; Wong R. S.-M. Synthesis, characterization and photovoltaic behavior of platinum acetylide polymers with electron-deficient 9,10-anthraquinone moiety. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 1189–1197. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.08.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Wang Q.; Wong W.-Y. New low-bandgap polymetallaynes of platinum functionalized with a triphenylamine-benzothiadiazole donor–acceptor unit for solar cell applications. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 432–440. 10.1039/C0PY00273A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Liu L.; Chen M.; Yang J.; Liu S.-Z.; Du Z.-L.; Wong W.-Y. Preparation, characterization, and electrical properties of dual-emissive Langmuir-Blodgett films of some europium-substituted polyoxometalates and a platinum polyyne polymer. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 879–888. 10.1002/pola.23839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Wong W.-Y.; Chow W.-C.; Cheung K.-Y.; Fung M.-K.; Djurisic A. B.; Chan W.-K. Harvesting solar energy using conjugated metallopolyyne donors containing electron-rich phenothiazine–oligothiophene moieties. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 694, 2717–2726. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2009.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Ho C.-l.; Wong W.-y. Synthesis, Characterization and Photoluminescent Properties of New Platinum-Containing Poly (fluorenyleneethynylene) Anchored with Carbazole Pendants. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2009, 27, 455–464. 10.1142/S0256767909004126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Wong W.-Y.; Guo Y.; Ho C.-L. Synthesis, Optical Properties and Photophysics of Group 10–12 Transition Metal Complexes and Polymer Derived from a Central Tris(p-ethynylphenyl)amine Unit. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2009, 19, 46–54. 10.1007/s10904-008-9233-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j Liu L.; Ho C.-L.; Wong W.-Y.; Cheung K.-Y.; Fung M.-K.; Lam W.-T.; Djurisic A. B.; Chan W.-K. Effect of Oligothienyl Chain Length on Tuning the Solar Cell Performance in Fluorene-Based Polyplatinynes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 2824–2833. 10.1002/adfm.200800439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; k Liu L.; Qiao L.-X.; Liu S.-Z.; Cui D.-M.; Zhang C.-M.; Zhou Z.-J.; Du Z.-L.; Wong W.-Y. Polyplatinayne/polyoxometalate composite Langmuir-Blodgett films: Preparation, structural characterization, and potential optoelectronic applications. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2008, 46, 3193–3206. 10.1002/pola.22654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; l Wong W.-Y.; Poon S.-Y. Synthesis, Characterization and Photoluminescence of Dimeric and Polymeric Metallaynes of Group 10–12 Metals Containing Conjugation-breaking Diphenylmethane Unit. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2008, 18, 155–162. 10.1007/s10904-007-9180-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; m Yang L.; Feng J.-K.; Wong W.-Y.; Poon S.-Y. Electronic structure and optical properties of germanium-bridged platinum(II)-containing diethynylfluorene monomer and oligomers: A theoretical investigation. Polymer 2007, 48, 6457–6463. 10.1016/j.polymer.2007.06.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; n Wong W.-Y.; Poon S.-Y.; Shi J.-X.; Cheah K.-W. Synthesis, Optical Properties, and Photoluminescence of Organometallic Acetylide Polymers of Platinum Functionalized with Si and Ge-Bridged Bis(3,6-Diethynyl-9-butylcarbazole). J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2007, 17, 189–200. 10.1007/s10904-006-9082-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; o Liu L.; Wong W.-Y.; Shi J.-X.; Cheah K.-W.; Lee T.-H.; Leung L. M. Synthesis, spectroscopy, structures and photophysics of metal alkynyl complexes and polymers containing functionalized carbazole spacers. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006, 691, 4028–4041. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2006.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; p Wong W.-Y.; Poon S.-Y.; Shi J.-X.; Cheah K.-W. Synthesis and light-emitting properties of platinum-containing oligoynes and polyynes derived from oligo(fluorenyleneethynylenesilylene)s. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2006, 44, 4804–4824. 10.1002/pola.21588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; q Liu L.; Wong W.-Y.; Poon S.-Y.; Cheah K.-W. Synthesis, Characterization and Optoelectronic Properties of Dimeric and Polymeric Metallaynes Derived from 3,6-Bis(buta-1,3-diynyl)-9-butylcarbazole. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2005, 15, 555–567. 10.1007/s10904-006-9009-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; r Liu L.; Wong W.-Y.; Poon S.-Y.; Shi J.-X.; Cheah K.-W.; Lin Z. Effect of Acetylenic Chain Length on the Tuning of Functional Properties in Fluorene-Bridged Polymetallaynes and Their Molecular Model Compounds. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 1369–1378. 10.1021/cm052655a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; s Ho C. L.; Yu Z. Q.; Wong W. Y. Multifunctional polymetallaynes: properties, functions and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5264–5295. 10.1039/C6CS00226A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; t Ho C. L.; Wong W. Y. Metal-containing polymers: Facile tuning of photophysical traits and emerging applications in organic electronics and photonics. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 2469–2502. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; u Ho C. L.; Wong W. Y. Charge and energy transfers in functional metallophosphors and metallopolyynes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 1614–1649. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; v Wong W. Y.; Ho C. L. Di-, oligo-and polymetallaynes: syntheses, photophysics, structures and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 2627–2690. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; w Wong W.-Y. Luminescent organometallic poly (aryleneethynylene)s: functional properties towards implications in molecular optoelectronics. Dalton Trans. 2007, 0, 4495–4510. 10.1039/b711478h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; x Wong W. Y. Molecular design, synthesis and structure-property relationship of oligothiophene-derived metallaynes. Comments Inorg. Chem. 2005, 26, 39–74. 10.1080/02603590590920514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhan H.-M.; Lamare S.; Ng A.; Kenny T.; Guernon H.; Chan W.-K.; Djurisic A. B.; Harvey P. D.; Wong W.-Y. Synthesis and Photovoltaic Properties of New Metalloporphyrin-Containing Polyplatinyne Polymers. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 5155–5167. 10.1021/ma2006206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Goudreault T.; He Z.; Guo Y.; Ho C.-L.; Zhan H.; Wang Q.; Ho K. Y.-F.; Wong K.-L.; Fortin D.; Yao B.; Xie Z.; Wang L.; Kwok W.-M.; Harvey P. D.; Wong W.-Y. Synthesis, Light-Emitting, and Two-Photon Absorption Properties of Platinum-Containing Poly(arylene-ethynylene)s Linked by 1,3,4-Oxadiazole Units. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 7936–7949. 10.1021/ma1009319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Soliman A. M.; Zysman-Colman E.; Harvey P. D. Strategic Modulation of the Photonic Properties of Conjugated Organometallic Pt–Ir Polymers Exhibiting Hybrid CT-Excited States. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2015, 36, 627–632. 10.1002/marc.201400542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang X.; Fortin D.; Brisard G.; Harvey P. D. Drastic Tuning of the Photonic Properties of ″(Push–Pull)n″ trans-Bis(ethynyl)bis(Tributylphosphine)Platinum(II)-Containing Polymers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2014, 35, 992–997. 10.1002/marc.201400018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Soliman A. M.; Fortin D.; Zysman-Colman E.; Harvey P. D. Unexpected evolution of optical properties in Ir–Pt complexes upon repeat unit increase: towards an understanding of the photophysical behaviour of organometallic polymers. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 6271–6273. 10.1039/c2cc32492j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Soliman A. M.; Fortin D.; Zysman-Colman E.; Harvey P. D. Photonics of a Conjugated Organometallic Pt–Ir Polymer and Its Model Compounds Exhibiting Hybrid CT Excited States. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2012, 33, 522–527. 10.1002/marc.201100721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Gagnon K.; Aly S. M.; Brisach-Wittmeyer A.; Bellows D.; Berube J.-F.; Caron L.; Abd-El-Aziz A. S.; Fortin D.; Harvey P. D. Conjugated Oligomers and Polymers of cis- and trans-Platinum(II)-para- and ortho-bis(ethynylbenzene)quinone Diimine. Organometallics 2008, 27, 2201–2214. 10.1021/om7010563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Cekli S.; Winkel R. W.; Schanze K. S. Effect of Oligomer Length on Photophysical Properties of Platinum Acetylide Donor–Acceptor–Donor Oligomers. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 5512–5521. 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b03977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Price R. S.; Dubinina G.; Wicks G.; Drobizhev M.; Rebane A.; Schanze K. S. Polymer Monoliths Containing Two-Photon Absorbing Phenylenevinylene Platinum(II) Acetylide Chromophores for Optical Power Limiting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 10795–10805. 10.1021/acsami.5b01456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Chen Z.; Hsu H.-Y.; Arca M.; Schanze K. S. Triplet Energy Transport in Platinum-Acetylide Light Harvesting Arrays. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 7198–7209. 10.1021/jp509130b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Goswami S.; Wicks G.; Rebane A.; Schanze K. S. Photophysics and non-linear absorption of Au(I) and Pt(II) acetylide complexes of a thienyl-carbazole chromophore. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 17721–17728. 10.1039/C4DT02123A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Shelton A. H.; Price R. S.; Brokmann L.; Dettlaff B.; Schanze K. S. High Efficiency Platinum Acetylide Nonlinear Absorption Chromophores Covalently Linked to Poly(methyl methacrylate). ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 7867–7874. 10.1021/am401834f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Ogawa K.; Guo F.; Schanze K. S. Phosphorescence quenching of a platinum acetylide polymer by transition metal ions. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2009, 207, 79–85. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2009.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Mei J.; Ogawa K.; Kim Y.-G.; Heston N. C.; Arenas D. J.; Nasrollahi Z.; McCarley T. D.; Tanner D. B.; Reynolds J. R.; Schanze K. S. Low-Band-Gap Platinum Acetylide Polymers as Active Materials for Organic Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2009, 1, 150–161. 10.1021/am800104k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Guo F.; Ogawa K.; Kim Y.-G.; Danilov E. O.; Castellano F. N.; Reynolds J. R.; Schanze K. S. A fulleropyrrolidine end-capped platinum-acetylide triad: the mechanism of photoinduced charge transfer in organometallic photovoltaic cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 2724–2734. 10.1039/b700379j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Guo F.; Kim Y.-G.; Reynolds J. R.; Schanze K. S. Platinum–acetylide polymer based solar cells: involvement of the triplet state for energy conversion. Chem. Commun. 2006, 0, 1887–1889. 10.1039/B516086C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Westlund R.; Malmstroem E.; Lopes C.; Oehgren J.; Rodgers T.; Saito Y.; Kawata S.; Glimsdal E.; Lindgren M. Efficient Nonlinear Absorbing Platinum(II) Acetylide Chromophores in Solid PMMA Matrices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 1939–1948. 10.1002/adfm.200800265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Fratoddi I.; Battocchio C.; Groia A. L.; Russo M. V. Nanostructured polymetallaynes of controlled length: Synthesis and characterization of oligomers and polymers from 1,1′-bis-(ethynyl)4,4′-biphenyl bridging Pt(II) or Pd(II) centers. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2007, 45, 3311–3329. 10.1002/pola.22081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Vestberg R.; Westlund R.; Eriksson A.; Lopes C.; Carlsson M.; Eliasson B.; Glimsdal E.; Lindgren M.; Malmstroem E. Dendron Decorated Platinum(II) Acetylides for Optical Power Limiting. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 2238–2246. 10.1021/ma0523670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Jura M.; Koentjoro O. F.; Raithby P. R.; Sharp E. L.; Wilson P. J. Optical and Electronic Properties of Metal-containing Poly-ynes and their Organic Precursors. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 2005, 846, 59–64. 10.1557/PROC-846-DD3.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matassa R.; Fratoddi I.; Rossi M.; Battocchio C.; Caminiti R.; Russo M. V. Two-Dimensional Networks of Ag Nanoparticles Bridged by Organometallic Ligand. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 15795–15800. 10.1021/jp304407p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Reichert J.; Ochs R.; Beckmann D.; Weber H. B.; Mayor M.; Löhneysen H. v. Driving Current through Single Organic Molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 176804 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.176804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Webera H. B.; Reicherta J.; Ochsa R.; Beckmann D.; Mayora M.; Löhneysen H. v. Conductance properties of single-molecule junctions. Phys. E 2003, 18, 231–232. 10.1016/S1386-9477(02)00986-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Mayor M.; von Hänisch C.; Weber H. B.; Reichert J.; Beckmann D. A trans-Platinum(II) Complex as a Single-Molecule Insulator. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1183–1186. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnot A.; Juvenal F.; Lapprand A.; Fortin D.; Knorr M.; Harvey P. D. Can Highly Flexible Copper (I) Cluster-containing 1D and 2D Coordination Polymers Exhibit MOF-like Properties?. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 11413–11421. 10.1039/C6DT01375A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bonnot A.; Knorr M.; Guyon F.; Kubicki M. M.; Rousselin Y.; Strohmann C.; Fortin D.; Harvey P. D. 1,4-Bis(arylthio)but-2-enes as Assembling Ligands for (Cu2X2)n (X = I, Br; n = 1, 2) Coordination Polymers: Aryl Substitution, Olefin Configuration, and Halide Effects on the Dimensionality, Cluster Size, and Luminescence Properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 774–788. 10.1021/acs.cgd.5b01360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Knorr M.; Bonnot A.; Lapprand A.; Khatyr A.; Strohmann C.; Kubicki M. M.; Rousselin Y.; Harvey P. D. Reactivity of CuI and CuBr toward Dialkyl Sulfides RSR: From Discrete Molecular Cu4I4S4 and Cu8I8S6 Clusters to Luminescent Copper(I) Coordination Polymers. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 4076–4093. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Harvey P. D.; Bonnot A.; Lapprand A.; Strohmann C.; Knorr M. Coordination RC6H4S(CH2)8SC6H4R/(CuI)n Polymers (R (n) = H (4); Me (8)): An Innocent Methyl Group that Makes the Difference. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2015, 36, 654–659. 10.1002/marc.201400659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Knorr M.; Khatyr A.; Dini A Ahmed; El Yaagoubi A.; Strohmann C.; Kubicki M. M.; Rousselin Y.; Aly S. M.; Fortin D.; Lapprand A.; Harvey P. D. Copper(I) Halides (X = Br, I) Coordinated to Bis(arylthio)methane Ligands: Aryl Substitution and Halide Effects on the Dimensionality, Cluster Size, and Luminescence Properties of the Coordination Polymers. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 5373–5387. 10.1021/cg500905z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lang H.; del Villar A.; Walfort B.; Rheinwald G. Synthesis and reactivity of platinum (II) and copper (I) coordination polymers; the solid-state structure of trans-(Ph3PhPt [(, 2_C=-CPh) CuBrh}n and trans-(Ph3PhPt [(, 2-e-= CPh) CuN]2. J. Organomet. Chem. 2004, 689, 1464–1471. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2003.11.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lang H.; del Villar A.; Walfort B. {trans-(Ph3P)2Pt[(μ-σ,η2-C≡CPh)AgOTf]2}n: a novel coordination polymer with Pt(C≡CPh)2 and Ag[μ-OS(O)(CF3)O]2Ag linkages. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2004, 7, 694–697. 10.1016/j.inoche.2003.08.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter J. P.; Lukehart C. M. Probing the electronic structure of selected diplatinum (μ-alkenylidene) complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1991, 190, 7–10. 10.1016/S0020-1693(00)80225-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Juvenal F.; Langlois A.; Bonnot A.; Fortin D.; Harvey P. D. Luminescent 1D- and 2D-Coordination Polymers using CuX Salts (X = Cl, Br, I) and a Metal-containing Dithioether Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 11096–11109. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b01703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chatt J.; Shaw B. L. 808. Alkyls and aryls of transition metals. Part II. Platinum (II) derivatives. J. Chem. Soc. 1959, 0, 4020–4033. 10.1039/jr9590004020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Hsung R. P.; Babcock J. R.; Chidsey C. E. D.; Sita L. R. Thiophenol protecting groups for the palladium-catalyzed heck reaction: Efficient syntheses of conjugated arylthoils. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 4525–4528. 10.1016/0040-4039(95)00861-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Dai C.; Yuan Z.; Collings J. C.; Fasina T. M.; Thomas R. Ll; Roscoe K. P.; Stimson L. M.; Yufit D. S.; Batsanov A. S.; Howard J. A. K.; Marder T. B. Crystal engineering with p-substituted 4-ethynylbenzenes using the C–H···O supramolecular synthon. CrystEngComm 2004, 6, 184–188. 10.1039/B404502E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roques N.; Mouchaham G.; Duhayon C.; Brandès S.; Tachon A.; Weber G.; Bellat J. P.; Sutter J. P. A Robust Nanoporous Supramolecular Metal–Organic Framework Based on Ionic Hydrogen Bonds. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 11690–11694. 10.1002/chem.201403638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Landers J.; Gor G. Y.; Neimark A. V. D. Density functional theory methods for characterization of porous materials. Colloids Surf., A 2013, 437, 3–32. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2013.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Vaidhyanathan R.; Iremonger S. S.; Dawson K. W.; Shimizu G. K. H. An amine-functionalized metal organic framework for preferential CO2 adsorption at low pressures. Chem. Commun. 2009, 5230–5232. 10.1039/b911481e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae Y.-S.; Yazaydın A. O.; Snurr R. Q. Evaluation of the BET Method for Determining Surface Areas of MOFs and Zeolites that Contain Ultra-Micropores. Langmuir 2010, 26, 5475–5483. 10.1021/la100449z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAINT; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, 2008.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.