Abstract

Relativistic and nonrelativistic density functional theory calculations were used to investigate rare or nonexistent ruthenium and osmium analogues of nitrosylhemes. Strong ligand field effects and, to a lesser degree, relativistic effects were found to destabilize {RuNO}7 porphyrins relative to their {FeNO}7 analogues. Substantially stronger relativistic effects account for the even greater instability and/or nonexistence of {OsNO}7 porphyrin derivatives.

Introduction

“Compounds whose structures do not offend the normal rules of valence, but which are nevertheless characterized by a low degree of stability”, reviewed by Dasent over a half-century ago,1,2 continue to fascinate chemists.3 The ruthenium and osmium analogues of nitrosylhemes4,5 arguably provide paradigmatic examples of such species. Transition-metal nitrosyls6−10 are conveniently described in terms of the Enemark–Feltham notation,11 which assigns an effective d electron count to a metal center and consists of the sum of the numbers of metal d and NO π* electrons. According to this notation, nitrosylheme is an {FeNO}7 complex, which may be formally thought of as derived from Fe(II), a d6 ion, and NO•. Unlike nitrosylhemes, which are stable and widespread in both biology and coordination chemistry, analogous {RuNO}7 porphyrin species have only been characterized in solution as electrogenerated species12−14 and genuine {OsNO}7 porphyrins, to our knowledge, remain unknown.15 In a similar vein, only a small handful of nonporphyrin {RuNO}7 and {OsNO}7 species have been reported, generally only as solution-state species.16−23 Presented herein is a density functional theory (DFT) study aimed at explaining the rarity and instability of {RuNO}7 and {OsNO}7 porphyrins. In particular, we have sought to determine whether relativistic effects24 play a significant role in influencing the stability of these species.

Given that there is no such thing as a nonrelativistic reality, relativistic effects by definition are purely theoretical quantities. For a given property, the relativistic effect consists of the difference between a value calculated at an adequately high level of relativistic theory and that calculated with an analogous nonrelativistic theory. Over a series of studies on porphyrinoid complexes involving group 6,25−27 7,28,29 8,30−32 and 1133−35 elements, we and others have found that, for the 5d elements, relativistic effects affect redox potentials by up to a few hundred mV and UV–vis absorption maxima by several tens of nm; relativistic effects on the analogous 4d complexes are by comparison much smaller. Here, we have used relativistic and nonrelativistic DFT calculations on two series of {MNO}7 porphyrins, viz., the five-coordinate (5c) M(Por)(NO) series and the six-coordinate (6c) M(Por)(NO)(ImH) series (M = Fe, Ru, Os; Por = porphyrinato; ImH = imidazole), to assess the importance of nonrelativistic ligand field effects and relativistic effects to the relative stabilities of the complexes.

Results and Discussion

The BP8636,37-D338/STO-TZ2P and B3LYP36,39,40-D3/STO-TZ2P optimized geometries of the molecules do not warrant a great deal of comment (Table 1). The calculations largely reproduce the short, experimentally observed Fe–N(O) distances, significantly longer Fe–N(ImH) distances (a reflection of the trans influence of NO), and FeNO angles of ∼140°. The calculations also reproduce (not shown here) the experimentally observed tilting of the Fe–N(O) vector relative to the heme normal and the asymmetry of the equatorial Fe–N bonds.41,42 Although there are no experimental precedents, the heavy element complexes Ru(Por)(NO), Ru(Por)(NO)(ImH), and Os(Por)(NO) exhibit the same structural trends. Curiously, scalar-relativistic zeroth-order regular approximation (ZORA)43,44 BP86-D3 calculations yield a dramatically anomalous optimized geometry for Os(Por)(NO)(ImH), characterized by a linear OsNO unit. Analogous scalar-relativistic B3LYP-D3 calculations, on the other hand, yield the expected bent geometry. Another notable point is that the scalar-relativistic BP86-D3 calculations predict a significant shortening of the Os–N(O) distance in Os(Por)(NO)(ImH), relative to its 5-coordinated analogue Os(Por)(NO), whereas all the other calculations indicate a lengthening of the M–N(O) distance in the presence of the imidazole ligand.

Table 1. Scalar-Relativistic (rel) and Nonrelativistic (nrel) Structural Parameters (Å, deg) for the Five- (5c) and Six-Coordinate (6c) Complexes Obtained from BP86-D3/TZ2P (without Parentheses) and B3LYP-D3/TZ2P (in Parentheses) Geometry Optimizations.

| Fe(Por)(NO) |

Ru(Por)(NO) |

Os(Por)(NO) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5c | nrel | rel | nrel | rel | nrel | rel |

| M–N(NO) | 1.698 (1.796) | 1.690 (1.792) | 1.827 (1.831) | 1.811 (1.808) | 1.862 (1.866) | 1.807 (1.809) |

| N–O | 1.176 (1.164) | 1.177 (1.170) | 1.183 (1.167) | 1.187 (1.177) | 1.185 (1.171) | 1.197 (1.189) |

| M–N1 | 1.998 (2.009) | 1.993 (2.007) | 2.062 (2.069) | 2.053 (2.060) | 2.081 (2.078) | 2.052 (2.061) |

| M–N2 | 2.026 (2.026) | 2.021 (2.024) | 2.082 (2.086) | 2.072 (2.078) | 2.091 (2.088) | 2.070 (2.073) |

| ∠M–N–O | 144.6 (140.9) | 144.6 (141.2) | 139.9 (140.6) | 140.8 (140.5) | 138.7 (138.5) | 143.8 (142.4) |

| Fe(Por)(NO)(ImH) |

Ru(Por)(NO) |

Os(Por)(NO)(ImH) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6c | nrel | rel | nrel | rel | nrel | rel |

| M–N(NO) | 1.739 (1.791) | 1.733 (1.774) | 1.880 (1.910) | 1.858 (1.878) | 1.914 (1.943) | 1.762 (1.863) |

| N–O | 1.181 (1.162) | 1.182 (1.166) | 1.186 (1.169) | 1.188 (1.177) | 1.186 (1.172) | 1.176 (1.186) |

| M–N1 | 2.005 (2.013) | 2.000 (2.011) | 2.068 (2.074) | 2.058 (2.061) | 2.079 (2.079) | 2.074 (2.061) |

| M–N2 | 2.023 (2.024) | 2.018 (2.027) | 2.073 (2.077) | 2.063 (2.072) | 2.082 (2.083) | 2.076 (2.068) |

| M–N(Im) | 2.107 (2.078) | 2.097 (2.102) | 2.167 (2.179) | 2.154 (2.177) | 2.152 (2.157) | 2.133 (2.174) |

| ∠M–N–O | 139.5 (138.7) | 139.4 (139.3) | 139.0 (141.2) | 140.6 (139.7) | 142.8 (140.1) | 179.8 (143.6) |

Depending on the functional, the nonrelativistic calculations indicate a modest to substantial lowering of the adiabatic ionization potentials (IPs) for the 5-coordinated series down the group 8 triad, a reflection of the greater ligand field destabilization of eg-type (in Oh symmetry) 4d and 5d orbitals relative to the 3d orbitals (Table 2). The sixth ligand also exerts a major influence on the IPs, lowering them by up to an eV, relative to the 5-coordinated series. By and large, relativistic effects on the IPs proved marginal (<0.1 eV) for Fe, slightly higher for Ru (∼0.2 eV), and substantial (∼0.5 eV) for the 5-coordinate Os complex, consistent with the expected relativistic destabilization of the Os 5d orbitals relative to the Ru 4d orbitals. Once again, the scalar-relativistic BP86-D3 results on Os(Por)(NO)(ImH) proved anomalous, predicting a modest 0.1 eV lowering of the adiabatic IP relative to the nonrelativistic BP86-D3 calculations.

Table 2. Nonrelativistic (nrel) and Scalar-relativistic (rel) Adiabatic IPs (in eV) of the Complexes Studied: BP86-D3/TZ2P and B3LYP-D3/TZ2P (within Parentheses).

| complexes | nrel | rel |

|---|---|---|

| Fe(Por)(NO) | 6.27 (6.71) | 6.22 (6.63) |

| Ru(Por)(NO) | 5.92 (6.00) | 5.79 (5.83) |

| Os(Por)(NO) | 5.82 (5.78) | 5.38 (5.27) |

| Fe(Por)(NO)(ImH) | 5.41 (5.81) | 5.35 (5.79) |

| Ru(Por)(NO)(ImH) | 5.06 (5.21) | 4.91 (5.00) |

| Os(Por)(NO)(ImH) | 4.79 (4.98) | 4.69 (4.47) |

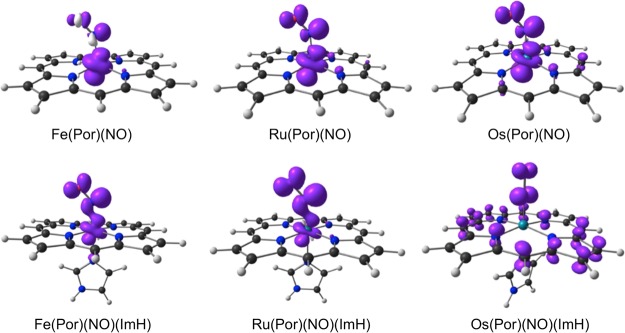

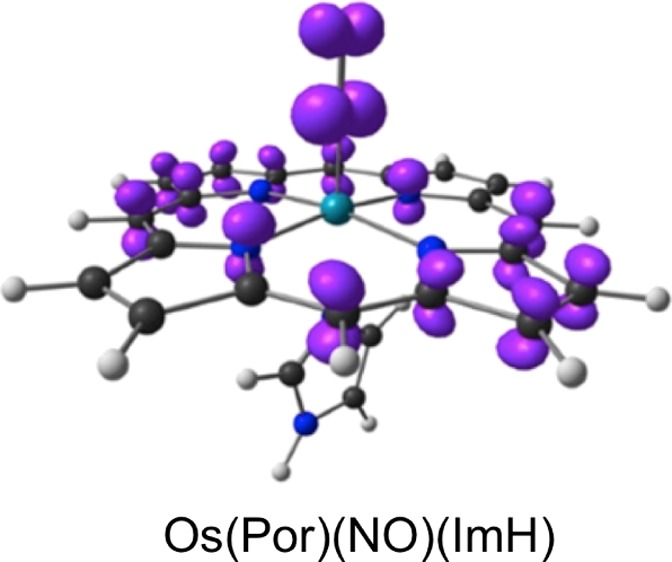

An examination of the scalar-relativistic spin density profiles of the complexes studied (Table 3 and Figure 1) provided an explanation for the above anomalous findings. The presence of a sixth ligand in {FeNO}7 porphyrins generally drives much of the spin density from the metal to the NO,45,46 which is indeed what is observed; the Ru spin density profiles also reveal the same trend. For Os(Por)(NO)(ImH), on the other hand, the scalar-relativistic spin density profile proved dramatically different, which is consistent with an essentially {OsNO}6–Por•3– radical formulation. This computational result nicely parallels experimental observations by Richter-Addo and coworkers,15 who concluded on the basis of infrared spectroelectrochemical studies that one-electron reduction of Os[OEP](NO)(SEt) (OEP = octaethylporphyrin) initially yields an {OsNO}6–Por•3– radical anion, which subsequently, presumably upon valence tautomerism, loses NO. The {OsNO}6–Por•3– formulation provides a simple explanation for the linearity of the OsNO unit and the short Os–N(O) distance for Os(Por)(NO)(ImH).

Table 3. Selected Mulliken Spin Populations from ZORA Scalar-relativistic BP86-D3/TZ2P and B3LYP-D3/TZ2P (in Parentheses) Calculations.

| complex | M | N | O |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe(Por)(NO) | 0.931 (0.861) | 0.056 (0.162) | 0.005 (0.068) |

| Ru(Por)(NO) | 0.575 (0.477) | 0.213 (0.289) | 0.124 (0.173) |

| Os(Por)(NO) | 0.489 (0.456) | 0.226 (0.288) | 0.131 (0.172) |

| Fe(Por)(NO)(ImH) | 0.511 (0.194) | 0.297 (0.503) | 0.174 (0.297) |

| Ru(Por)(NO)(ImH) | 0.175 (0.146) | 0.421 (0.504) | 0.262 (0.304) |

| Os(Por)(NO)(ImH) | –0.040 (0.074) | 0.140 (0.490) | 0.083 (0.299) |

Figure 1.

Scalar-relativistic BP86-D3 spin density plots for the complexes studied. Majority and minority spin densities are shown in purple and ivory, respectively.

Conclusions

Low IPs, which translate to low oxidation potentials, provide a partial explanation for the rarity and/or nonexistence of {RuNO}7 and {OsNO}7 porphyrin complexes. Relativistic effects play a particularly major role in lowering the IPs of potential {OsNO}7 species. The sixth ligand plays a critically important role in determining the stability of the species in question: the {MNO}7 state may spontaneously lose NO or otherwise decompose in the presence of strong-field trans ligands such as alkoxide, thiolate, or aryl. The equatorial ligand is also important; thus, whereas electroreduction of certain {RuNO}6 porphyrins occurs reversibly and yields {RuNO}7 species in solution,12−14 electroreduction of {RuNO}6 corroles occurs irreversibly, with concomitant loss of NO.32 Last but not least, the fact that the BP86-D3 and B3LYP-D3 methods afford radically different electronic descriptions for the six-coordinate {OsNO}7 model complex underscores the need for further methodological investigations for heavy-element–containing compounds, especially for open-shell 4d and 5d transition-metal complexes.

Computational Methods

All calculations were carried out with the Amsterdam Density Functional (ADF 2016)47,48 program system (see above for additional details). Relativistic effects were taken into account via the ZORA approximation to the two-component Dirac equation, applied both as a scalar correction and with spin–orbit coupling (SOC). For structural parameters and IPs, the SOC results proved essentially identical to those obtained from scalar relativistic calculations; accordingly, only the latter are explicitly tabulated in this paper. Suitably tight convergence criteria were used throughout, as implemented in the ADF program system. Frequency analyses were performed for all optimized geometries to confirm the absence of imaginary frequencies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants 262229 and 179568 from the Research Council of Norway and the National Research Fund of the Republic of South Africa.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b01434.

Optimized Cartesian coordinates (26 pages) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Dasent W. E.Nonexistent Compounds: Compounds of Low Stability; Marcel Dekker: New York, 1965; pp 1–182. [Google Scholar]

- Dasent W. E. Non-existent compounds. J. Chem. Educ. 1963, 40, 130–134. 10.1021/ed040p130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann R. Why Think Up New Molecules?. Am. Sci. 2008, 96, 372–374. 10.1511/2008.74.372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Smallest Biomolecules: Diatomics and their Interactions with Heme Proteins; Ghosh A., Ed.; Elsevier, 2008; pp 1–603. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt A. P.; Lehnert N. Heme-Nitrosyls: Electronic Structure Implications for Function in Biology. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2117–2125. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter-Addo G. B.; Legzdins P.. Metal Nitrosyls; Oxford University Press: New York, 1992; pp. 353–384 [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie G. R. A.; Scheidt W. R. Solid-State Structures of Metalloporphyrin NOx Compounds. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 1067–1090. 10.1021/cr000080p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. Metalloporphyrin–NO Bonding: Building Bridges with Organometallic Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005, 38, 943–954. 10.1021/ar050121+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A.; Hopmann K. H.; Conradie J.. Electronic Structure Calculations: Transition Metal–NO Complexes in Computational Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry, Solomon E. I.; Scott R. A.; King R. B., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Chichester, UK, 2009; pp. 389– 410. [Google Scholar]

- Mingos D. M. P.Historical Introduction to Nitrosyl Complexes; Structure and Bonding; Springer, 2014; Vol. 153, pp 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Enemark J. H.; Feltham R. D. Principles of structure, bonding, and reactivity for metal nitrosyl complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1974, 13, 339–406. 10.1016/s0010-8545(00)80259-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadish K. M.; Adamian V. A.; van Caemelbecke E.; Tan Z.; Tagliatesta P.; Bianco P.; Boschi T.; Yi G.-B.; Khan M. A.; Richter-Addo G. B. Synthesis, Characterization, and Electrochemistry of Ruthenium Porphyrins Containing a Nitrosyl Axial Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 1343–1348. 10.1021/ic950799t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P.; Das A. K.; Sarkar B.; Niemeyer M.; Roncaroli F.; Olabe J. A.; Fiedler J.; Záliš S.; Kaim W. Redox Properties of Ruthenium Nitrosyl Porphyrin Complexes with Different Axial Ligation: Structural, Spectroelectrochemical (IR, UV–Visible, and EPR), and Theoretical Studies. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 7106–7113. 10.1021/ic702371t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink J. R.; Abucayon E. G.; Ramuglia A. R.; Fadamin A.; Eilers J. E.; Richter-Addo G. B.; Shaw M. J. Electrochemical Investigation of the Kinetics of Chloride Substitution upon Reduction of [Ru(porphyrin)(NO)Cl] Complexes in Tetrahydrofuran. ChemElectroChem 2018, 5, 861–871. 10.1002/celc.201701001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter S. M.; Lee J.; Hixson C. A.; Powell D. R.; Wheeler R. A.; Shaw M. J.; Richter-Addo G. B. Fiber-optic infrared reflectance spectroelectrochemical studies of osmium and ruthenium nitrosyl porphyrins containing alkoxide and thiolate ligands. Dalton Trans. 2006, 1338–1346. 10.1039/b510717b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan R. W.; Brown G. M.; Meyer T. J. Reversible electron transfer to the nitrosyl group in ruthenium nitrosyl complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 894–895. 10.1021/ja00837a036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan R. W.; Meyer T. J. Reversible electron transfer in ruthenium nitrosyl complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1977, 16, 574–581. 10.1021/ic50169a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann F.; Kaim W.; Baraldo L. M.; Slep L. D.; Olabe J. A.; Fiedler J. Reduction of the NO+ ligand in the pentacyanonitrosylosmate(II) ion. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1999, 285, 129–133. 10.1016/s0020-1693(98)00254-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner M.; Scheiring T.; Kaim W.; Slep L. D.; Baraldo L. M.; Olabe J. A.; Záliš S.; Baerends E. J. EPR Characteristics of the [(NC)5M(NO)]3– Ions (M = Fe, Ru, Os). Experimental and DFT Study Establishing NO as a Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 5704–5707. 10.1021/ic010452s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieger M.; Sarkar B.; Záliš S.; Fiedler J.; Escola N.; Doctorovich F.; Olabe J. A.; Kaim W. Establishing the NO oxidation state in complexes [Cl5(NO)M]n–, M = Ru or Ir, through experiments and DFT calculations. Dalton Trans. 2004, 1797–1800. 10.1039/b404121f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz S.; Sarkar B.; Sieger M.; Kaim W.; Roncaroli F.; Olabe J. A.; Záliš S. EPR Insensitivity of the Metal-Nitrosyl Spin-Bearing Moiety in Complexes [LnRuII-NO•]k. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 2004, 2902–2907. 10.1002/ejic.200400042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P.; Sarkar B.; Sieger M.; Niemeyer M.; Fiedler J.; Záliš S.; Kaim W. The Metal–NO Interaction in the Redox Systems [Cl5Os(NO)]n–, n= 1–3, and cis-[(bpy)2ClOs(NO)]2+/+: Calculations, Structural, Electrochemical, and Spectroscopic Results. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 4602–4609. 10.1021/ic0517669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri G. K.; Kaim W. Electronic structure alternatives in nitrosylruthenium complexes. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 4471–4478. 10.1039/c002173c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyykkö P. Relativistic effects in chemistry: more common than you thought. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2012, 63, 45–64. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032511-143755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu A. B.; Vazquez-Lima H.; Gagnon K. J.; Ghosh A. Tungsten Biscorroles: New Chiral Sandwich Compounds. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22, 6914–6920. 10.1002/chem.201504848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu A. B.; Vazquez-Lima H.; McCormick L. J.; Ghosh A. Relativistic effects in metallocorroles: comparison of molybdenum and tungsten biscorroles. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 5830–5833. 10.1039/c7cc01549f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schies C.; Alemayehu A. B.; Vazquez-Lima H.; Thomas K. E.; Bruhn T.; Bringmann G.; Ghosh A. Relativistic effects in metallocorroles: comparison of molybdenum and tungsten biscorroles. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 5830–5833. 10.1039/C7CC01549F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einrem R. F.; Braband H.; Fox T.; Vazquez-Lima H.; Alberto R.; Ghosh A. Synthesis and Molecular Structure of 99Tc Corroles. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22, 18747–18751. 10.1002/chem.201605015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einrem R. F.; Gagnon K. J.; Alemayehu A. B.; Ghosh A. Metal-Ligand Misfits: Facile Access to Rhenium-Oxo Corroles by Oxidative Metalation. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22, 517–520. 10.1002/chem.201504307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao M.-S.; Scheiner S. Relativistic effects in iron-, ruthenium-, and osmium porphyrins. Chem. Phys. 2002, 285, 195–206. 10.1016/s0301-0104(02)00836-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu A. B.; Gagnon K. J.; Terner J.; Ghosh A. Oxidative Metalation as a Route to Size-Mismatched Macrocyclic Complexes: Osmium Corroles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 14411–14414. 10.1002/anie.201405890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu A. B.; Vazquez-Lima H.; Gagnon K. J.; Ghosh A. Stepwise Deoxygenation of Nitrite as a Route to Two Families of Ruthenium Corroles: Group 8 Periodic Trends and Relativistic Effects. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 5285–5294. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b00377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtfeger P. Relativistic effects in properties of gold. Heteroat. Chem. 2002, 13, 578–584. 10.1002/hc.10093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pyykkö P. Theoretical chemistry of gold. III. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1967–1997. 10.1039/b708613j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas K. E.; Vazquez-Lima H.; Fang Y.; Song Y.; Gagnon K. J.; Beavers C. M.; Kadish K. M.; Ghosh A. Ligand Noninnocence in Coinage Metal Corroles: A Silver Knife-Edge. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015, 21, 16839–16847. 10.1002/chem.201502150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys. 1988, 38, 3098–3100. 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P. Density-functional approximation for the correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1986, 33, 8822–8824. 10.1103/physrevb.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Perdew J. P. Erratum. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1986, 34, 7406. 10.1103/physrevb.34.7406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens P. J.; Devlin F. J.; Chabalowski C. F.; Frisch M. J. Ab Initio Calculation of Vibrational Absorption and Circular Dichroism Spectra Using Density Functional Force Fields. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 11623–11627. 10.1021/j100096a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidt W. R.; Duval H. F.; Neal T. J.; Ellison M. K. Intrinsic Structural Distortions in Five-Coordinate (Nitrosyl)iron(II) Porphyrinate Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 4651–4659. 10.1021/ja993995y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A.; Wondimagegn T. A Theoretical Study of Axial Tilting and Equatorial Asymmetry in Metalloporphyrin–Nitrosyl Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 8101–8102. 10.1021/ja000747p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Lenthe E.; Baerends E. J.; Snijders J. G. Relativistic regular two-component Hamiltonians. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 4597–4610. 10.1063/1.466059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Lenthe E.; Baerends E. J.; Snijders J. G. Relativistic total energy using regular approximations. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 101, 9783–9792. 10.1063/1.467943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tangen E.; Svadberg A.; Ghosh A. Toward modeling H-NOX domains: A DFT study of heme-NO complexes as hydrogen bond acceptors. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 7802–7805. 10.1021/ic050486q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praneeth V. K. K.; Haupt E.; Lehnert N. Thiolate coordination to Fe(II)–porphyrin NO centers. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2005, 99, 940–948. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The ADF program system uses methods described in:te Velde G.; Bickelhaupt F. M.; Baerends E. J.; Guerra C. F.; van Gisbergen S. J. A.; Snijders J. G.; Ziegler T. Chemistry with ADF. Comput. Chem. 2001, 22, 931–967. 10.1002/jcc.1056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For additional details on all aspects of the calculations, see the ADF program manual: http://www.scm.com/ADF/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.