Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

To report clinical predictors of transition to dementia in Motoric Cognitive Risk Syndrome (MCR); a pre-dementia syndrome characterized by cognitive complaints and slow gait.

METHODS:

We examined if cognitive or motoric impairments predicted transition to dementia in 610 older adults with MCR from three cohorts. Association of cognitive (Logical memory, Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), cognitive complaint severity and Mini-mental state examination (MMSE)) and motoric factors (gait velocity) with dementia risk was computed using Cox models.

RESULTS:

There were 156 incident dementias (134 Alzheimer’s disease). In the pooled sample, Logical memory (adjusted Hazard ratio (aHR) 0.91), cognitive complaint severity (aHR 1.53) and MMSE (aHR 0.75) predicted transition of MCR to dementia. CDR score ≥0.5 predicted dementia (aHR 3.18) in one cohort. Gait velocity did not predict dementia.

DISCUSSION:

While MCR is a motoric-based pre-dementia syndrome, severity of cognitive but not motoric impairments predicts conversion to dementia.

Keywords: Dementia, Cohort studies, Incidence studies, gait disorders, Motoric Cognitive Risk syndrome

INTRODUCTION

The Motoric Cognitive Risk Syndrome (MCR) is a pre-dementia syndrome characterized by the presence of cognitive complaints and slow gait in older individuals without dementia or disability.1, 2 MCR predicted risk of developing major cognitive decline and dementia (Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia) in over 5000 older adults from five independent aging cohorts, including the three cohorts in this study.1, 2 MCR has incremental predictive validity for dementia compared to its individual components of either subjective cognitive complaints or slow gait, and even after accounting for overlap with Mild Cognitive Impairment syndrome (MCI).1, 2 Subjective cognitive complaints are associated with reduced cognitive function and increased risk of dementia.3, 4 Gait changes in aging are multifactorial in nature with both neurological and non-neurological causes.5, 6 Nonetheless, presence of slow gait in older adults predicts dementia irrespective of the underlying etiology.2, 7 But, it is as yet not clear whether it is the severity of the cognitive or the motoric components at the time of diagnosis of MCR that predicts future transition to dementia. This information would be of practical value for clinicians assessing dementia risk in patients identified with MCR as well as help guide future research. Herein, we examine cognitive and motoric predictors of dementia in individuals with MCR from three prospective cohort studies.

METHODS

This MCR study includes individual data from participants from three established aging studies in USA: the Einstein Aging Study,2 the Rush Memory and Aging project8 and the Religious Orders Study.1 Individual study goals and design have been published. In brief, the Einstein Aging Study (EAS) is a prospective study of cognitive aging in community-dwelling adults age 70 and over in the Bronx county (mean age 79.3y, 62% women, 66% Caucasian, 28% African-American).2, 7 The Chicago-based Rush Memory and Aging project (MAP) is a clinical-pathologic study of chronic conditions of aging (mean age 79.7y, 74% women, 93% Caucasian, 6% African-American).8 The Religious Orders Study (ROS) enrolled religious clergy age 55 and over from more than 40 groups across USA (mean age 76.0y, 71% women, 92% Caucasian, 7% African-American).9

Baseline data was collected from 1994 to 2018 in the three cohorts, and follow-up ranged from 0 to 23 years. Two cohorts recruited regionally2, 8 and one nationally.9 All cohorts contained information at baseline and annual follow-up visits on cognitive complaints, cognitive tests, gait speed, mobility disability and dementia. From the 4,597 individuals at baseline across the three cohorts we excluded participants less than 60 years old (n = 33) and those missing gait speed (n = 354) or cognitive complaint assessments (n = 7). We excluded 211 participants diagnosed with dementia at diagnostic case conferences at or prior to the baseline visit for this analysis. Following exclusions, the eligible sample included 3,992 individuals aged 60 and older. Of the 3,992 individuals, 610 participants had MCR at baseline, and were included in the analysis.

All participating studies obtained written informed consent and approval from local institutional review boards. The institutional review board of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine approved this analysis.

MCR diagnosis:

MCR diagnosis adapts operational criteria for MCI,1 and is defined as presence of memory complaints and slow gait in older individuals without dementia or mobility disability.2 Memory complaints from participants were recorded by interviewers based on positive responses on the following two questions that were common to all three cohorts: ‘trouble remembering’ and ‘if memory was worse than 10 years ago.’2 Positive responses to both questions was ‘frequently’ or ‘sometimes’ in EAS and ‘very often’, ‘often’ and ‘sometimes’ in MAP and ROS. Unlike other pre-dementia syndromes, cognitive tests are not used or required for MCR diagnosis.1, 2 Informants were not available for all participants. Hence, informant reports were not used to define or confirm cognitive complaints. Gait speed (cm/sec) at normal pace was measured using an instrumented walkway (GAITRite, CIR systems) in EAS.10 Gait at normal pace was timed over a fixed distance from a standing start, and converted to speed (cm/sec) in MAP and ROS cohorts.9 Slow gait was defined as walking speed one standard deviation below age and sex specific means in each cohort to overcome variability in cohorts.2, 11 High reliability has been reported for gait speed measured using timed and instrumented methods.12 MCR prevalence rates in studies using timed gait and instrumented methods had excellent agreement.1

Dementia transition predictors:

We utilized four measures to examine cognitive predictors of MCR transition. We selected two measures that were independent of the dementia diagnosis procedure in each cohort: Logical memory test13 and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR).14 As a secondary step, we also examined two cognitive measures that were possibly dependent of the dementia diagnosis procedure: severity of subjective cognitive complaints and Mini-Mental State examination (MMSE) scores.

The Logical memory test, a story recall task from the Wechsler Memory Scale - revised,13 was administered in all cohorts using the same protocol, and was independent of the dementia diagnosis procedures in each cohort.15 The number of story units recalled immediately (range 0 to 25) was used as the predictor.

The CDR, a semi-structured interview with patient and caregiver, was done in all participants by study clinicians only in the EAS; blinded to neuropsychological test results and independent of dementia diagnosis. EAS study clinicians were also blinded to the results of the gait assessments. CDR score of ≥0.5 (mild or greater impairment) at time of MCR diagnosis was examined as an independent predictor of transition from MCR to dementia.

We identified four subjective cognitive complaint items assessed in all three cohorts: difficulty or inability managing medications or finances, trouble remembering, and if memory was worse than 10 years ago. Two of the four items were used in determining cognitive complaints for MCR diagnosis, as noted earlier. Hence, this measure could possibly be dependent on the dementia diagnosis procedure, though we did not use the individual cognitive complaint items for prognostication. We derived a severity score for the four subjective cognitive complaints items using item response theory (IRT).16 Specifically, we fit a 2-parameter IRT model for the subjective cognitive complaints items with logit link where the latent trait is scaled along theta, and the two item-wise parameters each represent item discrimination and item difficulty. IRT uses a likelihood approach to estimate the underlying factor, and can handle missing data under the missing at random (MAR) assumption. Parameters were estimated using the maximum likelihood method with robust standard errors. The estimate of the latent trait for each participant, which reflects the severity of cognitive complaints, was obtained using Bayes modal estimation, and is referred to as the ‘cognitive complaint severity score’. For the current analysis the range of this composite score within all of the samples was −0.43 to 2.09. Analyses were performed using Mplus 8. We also examined the predictive validity of a ‘cognitive complaint count’ (maximum score 4) based on the number of positive responses to the four questions used to derive the severity score. This secondary analysis was done only in the pooled sample due to missing data on responses to individual questions.

The EAS used the Blessed-Information-Memory-Concentration test to assess general mental status whereas MAP and ROS cohorts used the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).2, 8, 15 Total scores on these tests were not used in any cohort to assign dementia diagnosis. But MAP and ROS use orientation items on MMSE to assign dementia diagnosis but not the total score.17 We converted Blessed scores (range 0 to 32; lower better) in EAS to MMSE (range 0 to 30; higher better) using a validated conversion formula in order to have a common objective measure to test as a predictor in all cohorts.18 The results of our analyses were the same in the EAS when using either the original Blessed scores or transformed MMSE scores.

We examined gait speed (cm/sec) as the motoric predictor of transition to dementia. Everyone in this MCR sample met age and sex based criteria for slow gait. Hence, gait velocities examined as dementia predictor were all by definition within the slow gait range. As a secondary analysis, we examined gait speed dichotomized at 40 cm/sec, a common cutscore used to define mobility disability.19

Dementia diagnosis:

All available clinical and neuropsychological information on all subjects were reviewed at consensus case conferences in EAS, and dementia diagnosis was assigned using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual fourth edition19 and subtyped using established criteria for Alzheimer’s disease type dementia (AD).20 The MAP and ROS cohorts used a computer-based system of prediction rules to guide clinical judgment for the diagnosis of dementia and AD as it was not operationally feasible or cost-efficient to interview informants or perform case conferences for all evaluations.15 Good agreement between clinical dementia diagnoses and pathological findings were reported in all three cohorts.9, 15, 20–22

Analysis:

Results are reported for individual cohorts and pooling samples using meta-analysis. The onset of dementia was assigned at the follow-up visit at which criteria were met. Person-years of follow-up were calculated as the time between baseline visit and final follow-up examination or incident dementia, whichever occurred first. Cox proportional-hazards models were used to compute hazard ratios adjusted for age, sex and education (aHR) with 95% CI associated with the selected risk factors for developing incident dementia. The proportional hazards assumptions were examined graphically and analytically, and were adequately met for all variables except MMSE in the MAP cohort. In order to obtain an overall effect using a common model we conducted Cox proportional-hazard models in all samples for the meta-analysis, and reported differences among the cohorts separately. Statistical analyses were done using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.). The datasets used for the analyses are available at request from the individual studies.

RESULTS

Cohort characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were 610 individuals with prevalent MCR; 171 EAS, 268 MAP and 171 ROS. The ages of the 610 MCR participants ranged from 62 to 98 years, with 70% women. Mean education level was 14.8 years, which was explained by the higher education level in the ROS cohort. Over a median follow-up period of 2.9 years, 156 individuals in the pooled sample developed dementia (134 AD). Dementia rates and follow-up time for the individual cohorts are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of participating MCR cohorts.

| Variables | EAS | MAP | ROS | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample, n | 1,283 | 1,921 | 1,393 | 4,597 | |

| MCR sample, n (%) | 171 (13.3) | 268 (13.9) | 171 (12.3) | 610 (13.3) | |

| Study baseline year | 2002 | 1997 | 1994 | - | |

| Age Range | 70.4-98.5* | 62.9-98.7 | 64.8-98.2 | 62.9-98.7 | |

| Women, % | 63 | 74 | 69 | 70 | |

| Education, mean (SD) y | 13.7 (3.3) | 13.8 (4.0) | 17.5 (3.8) | 14.8 (4.1) | |

| Incident dementia among persons with MCR, n | 16 | 68 | 72 | 156 | |

| Post-MCR follow-up time, median (range) y | 1.1 (11.7) | 3.0 (14.3) | 6.5 (22.1) | 2.9 (22.1) | |

| Gait speed, mean (SD) cm/s | 58.4 (14.0)* | 35.7 (7.6) | 36.7 (11.3) | 42.4 (14.7) | |

| Slow gait cutscores (cm/s) | Men 60-74y | 88.1* | 50.5 | 56.6 | - |

| Men ≥75y | 72.3 | 45.1 | 44.5 | - | |

| Women 60-74y | 76.7* | 48.8 | 52.1 | - | |

| Women ≥75y | 66.5 | 40.7 | 36.9 | - | |

| Logical memory test Immediate recall, mean (SD) | 10.2 (4.0) | 10.0 (4.3) | 10.9 (4.3) | 10.3 (4.2) | |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 26.1 (1.6)** | 27.0 (2.9) | 27.8 (2.0) | 27.0 (2.5) | |

| BIMC, mean (SD) | 2.7 (2.2) | - | - | - | |

| Cognitive complaint severity score, mean (SD) | −0.2 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.6) | 0.1 (0.7) | 0.0 (0.6) | |

Abbreviations: EAS: Einstein Aging Study; MAP: Memory and Aging Project; ROS: Religious Orders Study; BIMC: Blessed-Information-Memory-Concentration test; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination.

EAS sample age of entry was 70 and over.

For EAS, MMSE scores were converted from BIMC scores.

Cognitive predictors:

Table 2 shows that the Logical memory immediate recall scores (higher better) predicted dementia in the pooled sample (aHR 0.91, 95% CI 0.87-0.96) as well as two out of the three cohorts.

Table 2. MCR transition to Incident dementia: cognitive and motoric predictors.

Cox proportional-hazards models with associations reported as Hazard ratios adjusted for age, sex, education (aHR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

| Predictors | EAS aHR (95% CI) | MAP aHR (95% CI) | ROS aHR (95% CI) | Pooled aHR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive predictors independent of dementia diagnosis | ||||

| Logical memory test Immediate recall (0-25) | 0.88 (0.78-0.98) | 0.90 (0.84-0.97) | 0.94 (0.88-1.01) | 0.91 (0.87-0.96) |

| CDR scale ≥0.5* | 3.18 (1.08-9.34) | - | - | - |

| Cognitive predictors possibly dependent of dementia diagnosis | ||||

| Cognitive complaint severity score | 2.19 (0.94-5.11) | 1.77 (1.20-2.61) | 1.28 (0.93-1.76) | 1.53 (1.16-2.02) |

| MMSE total score (0-32) | 0.73 (0.58-0.93) | 0.79 (0.70-0.88) | 0.70 (0.60-0.81) | 0.75 (0.69-0.81) |

| Motoric predictor | ||||

| Gait speed, cm/sec | 1.01 (0.96-1.07) | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) | 0.98 (0.96-1.01) | 0.99 (0.97-1.01) |

Abbreviations: EAS: Einstein Aging Study; MAP: Memory and Aging Project; ROS: Religious Orders Study; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; CDR: Clinical Dementia rating.

CDR only done in the EAS cohort.

Of the 171 EAS participants with MCR, the study clinicians rated 91 as 0, 72 as 0.5, and 8 as 1 on the CDR scale. CDR ≥0.5 predicted transition to dementia in EAS participants with MCR (aHR 3.18, 95% CI 1.08-9.34). The 8 cases with CDR of 1 at baseline did not meet dementia criteria at consensus case conferences. Results were in the same direction when these eight cases were excluded from this analysis, though not significant (aHR 2.53, 95% CI 0.81-7.95).

Table 2 shows that the cognitive complaint severity score at the visit at which MCR was diagnosed predicted transition to dementia in MAP as well as in the pooled sample (aHR 1.53, 95% CI 1.16-2.02). The cognitive complaint severity score also predicted transition to AD in the pooled sample (aHR 1.52, 95% CI 1.07-2.15).

General mental status assessed by MMSE (higher scores better) predicted transition to dementia in all three cohorts individually as well as in the pooled sample (aHR 0.75, 95% CI 0.69-0.81).

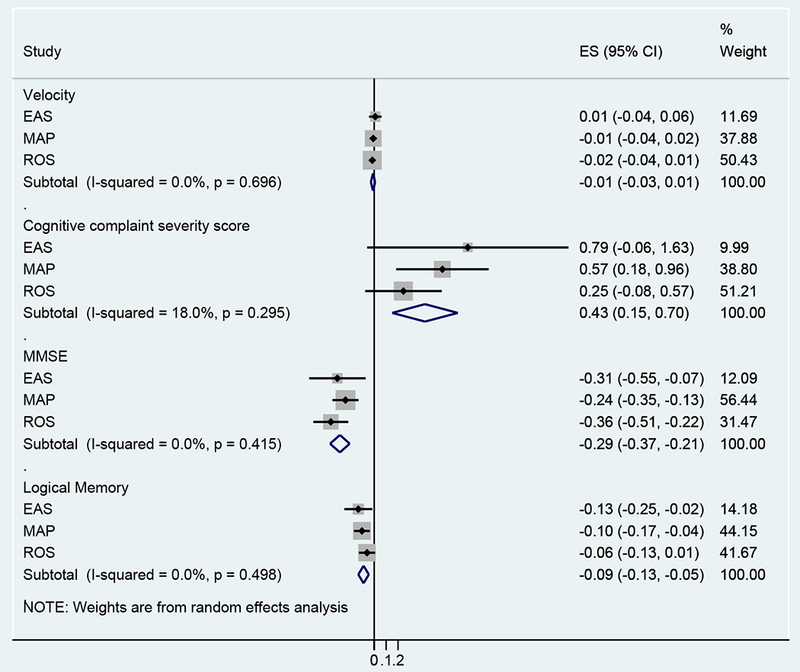

Figure 1 graphically shows the estimates (log of hazard ratios) for the association of prevalent MCR with risk of incident dementia in individual studies as well as in the pooled sample. The I2 statistic indicates shows good consistency across the three cohorts with low degree of heterogeneity.

Figure 1. MCR transition to Incident dementia: cognitive and motoric predictors.

The estimates (ES) are the log of Hazard Ratios. For each study the ES are graphically represented by dots and the horizontal bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. The grey boxes surrounding the dot graphically represent study weighting in the analysis, which is also shown in the last column. The diamond is the pooled estimate. EAS: Einstein Aging Study; MAP: Memory and Aging Project; ROS: Religious Orders Study

Motoric predictors:

Table 2 shows that gait speed was not a significant predictor of transition of MCR to dementia in the individual cohorts or in the pooled sample. Gait speed also did not predict transition to AD in the pooled sample (aHR 0.99, 95% CI 0.97-1.01).

The 299 individuals with MCR and gait speed ≤40 cm/sec were at higher risk of developing dementia compared to the 311 individuals with MCR with gait speed faster than 40 cm/sec (aHR 1.81, 95% CI 1.15-2.85). Of the 299 MCR cases with gait velocity ≤40 cm/sec, 30 had MMSE scores <24. When these 30 individuals with low MMSE scores were excluded, gait velocity ≤40 cm/sec did not predict dementia (aHR 1.41, 95% CI 0.86-2.31).

Sensitivity analyses:

The mean cognitive complaint count in the pooled sample was 1.3±0.8. The cognitive complaint count predicted transition to dementia in the pooled sample (aHR 1.30, 95% CI 1.01-1.68).

Given the well-described associations between cognitive and motor function,23 we examined the effect of their interaction on dementia risk. The interaction term between gait speed and MMSE scores did not predict transition to incident dementia in the pooled sample (aHR 0.99, 95% CI 0.91-1.07).

To allow for non-proportional hazard assumption for MMSE in the MAP cohort we included an interaction variable for time and MMSE in the model (aHR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02-1.07) indicating that the effect of MMSE is stronger at earlier time points and diminishes over time in MAP.

To account for diagnostic misclassification of dementia as MCR at baseline, we excluded 23 individuals who developed dementia in the first year of follow-up. Of the 8 EAS MCR cases rated as 1 on the CDR scale, three converted to dementia in the first year and five did not return for follow-up after their baseline visit. Hence, none of the CDR 1 cases were included in this sensitivity analysis. Logical memory (aHR 0.93, 95% CI 0.89-0.98) and MMSE scores (aHR 0.79, 95% CI 0.68-0.93) predicted dementia in the pooled sample, and the cognitive severity score (aHR 1.28, 95% CI 0.96-1.70) reached borderline significance.

DISCUSSION

MCR syndrome, which encompasses cognitive and motoric deficits, offers a clinically accessible approach to identifying patients at high risk for dementia in clinical settings that does not require extensive resources.1, 2 In this multi-center study of 610 persons with MCR syndrome aged 60 and older, severity of cognitive impairments at time of MCR diagnosis that was assessed in multiple ways was a more consistent predictor of transition from MCR to dementia than gait speed. Cognitive test performance, cognitive complaints and clinical rating of cognitive status predicted transition to incident dementia and incident AD. In contrast, speed within the slow gait range in individuals with MCR did not predict transition to dementia. This observation will be of practical prognostication value to clinicians diagnosing patients with MCR. Simple questions about severity and number of cognitive complaints could help clinicians determine who among their patients who meet criteria for MCR would progress to dementia. In our secondary analysis, each additional cognitive complaint was associated a 30 percent increased risk of transitioning from MCR to dementia. Our observations support MCR as a pre-dementia syndrome with a motoric phenotype but with dementia transition risk being driven by severity of cognitive impairments at the time of diagnosis.

The Logical memory test immediate recall scores were not used to assign dementia diagnoses in our cohorts. The CDR score was assigned in EAS by the study clinician without knowledge of neuropsychological or gait test results, and before the consensus diagnosis conference. The cognitive complaint severity score was derived using IRT methodology, and was not available for the dementia diagnostic procedures in any cohort. Impairment in basic activities of daily living but not in instrumental activities (included in the cognitive complaint severity score) were used to assign dementia diagnosis. The total MMSE score was not used to assign dementia diagnosis in MAP and ROS; only certain MMSE items were utilized in the diagnostic algorithm.15 While Blessed scores were not directly used to assign dementia diagnosis in EAS, diagnosticians may have been aware of the scores at case conferences. Hence, while our secondary measures (cognitive complaints severity and MMSE) may not have been completely independent of the dementia diagnosis, the consistency of the associations between these measures and dementia risk in all cohorts as well as the confirmation of the association by our independent primary measures (Logical memory test and CDR rating) lends confidence to the premise that severity of cognitive impairments at time of diagnosis of MCR drives dementia transition risk.

There is an extensive literature, including our previous studies,23, 24 which support slow gait as a dementia risk marker. In these studies, slow gait at baseline in older individuals without dementia predicted risk of developing incident dementia even after accounting for cognitive test performance.7, 23 Indeed, the MCR construct was based on these findings.1, 2 However, it appears that once older adults with slow gait develop cognitive complaints (and thus, meet MCR criteria1, 2), their risk of conversion to dementia is driven by their cognitive rather than their motoric status at the time of diagnosis. This is not to imply that slow gait is not predictive of dementia in general or that slow gait within the MCR group is not reflective of underlying brain pathology.25, 26 The slow gait component of MCR is a marker of brain pathologies that result in motor manifestations in their earliest stages. The predictive nature of cognitive complaints and tests in MCR patients may reflect worsening of dementia related pathology or spread of pathology into brain areas responsible for other non-motor behaviors and cognitive impairments associated with dementia.25, 26 Furthermore, gait variables other than speed might be more predictive of transition of MCR to dementia than gait speed.7, 27 More research, including clinicopathological investigations, are needed to build on these findings.

Gait speed within the MCR range, examined as a continuous variable, did not predict transition to dementia. Since our focus was only on individuals with MCR, the restricted range of gait velocities within this group may in part explain our negative finding. However, slow gait is the criterion used to define MCR. We reported that MCR has incremental predictive validity for dementia compared to slow gait alone in the overall populations in our participating cohorts.1, 2 Moreover, higher gait speeds (excluded by the MCR definition) are less likely to be associated with risk of developing dementia.7 A caveat was that individuals with MCR with slowest gait (defined dichotomously) had an increased risk of dementia. However, this risk is mostly explained by overlap of individuals with MCR in this slowest gait group with those with worse cognitive scores. Once these individuals were excluded, the slowest gait category did not predict transition of MCR to dementia. Furthermore, the interaction term between gait speed and MMSE scores did not predict transition to incident dementia. Utilizing only memory related questions in MCR diagnosis as well as the high proportion of AD among the incident dementia cases might be an alternate explanation for why cognitive complaints but not gait velocity predicts dementia. This issue needs to be further examined in future studies with other dementia subtypes and using a wider array of cognitive complaints.

A key strength is that our study was based on three large well-established aging cohorts with validated and reliable cognitive and motor assessment protocols as well as diagnostic procedures, and that partook in previous MCR studies.1, 2 We used cohort specific cutscores to determine slow gait to account for the variability in gait speed performance that has been reported between samples and across age groups,10, 11 and this slow gait definition is consistent with the approach used in our previous MCR studies.1, 2 Our sensitivity analyses account for alternate explanations such as interactions between cognitive and motor function. MCR cases did not have disability and were ambulatory; suggesting that this was a relatively healthy cohort. The mean MMSE scores for the MCR cases were high (26 to 28) in all cohorts. Also, 53% of MCR cases in EAS received a CDR rating of 0 and only 5% received a CDR rating of 1. Hence, it is unlikely that most MCR cases were at the cusp of dementia. Furthermore, we accounted for participants with dementia being misclassified as MCR by excluding those who did convert to dementia in the first year of follow-up.

Several limitations are noted. The composition of our cohorts needs to be considered while interpreting findings. The average level of education was high, especially in the ROS, and our findings should be tested in more diverse samples. As with any retrospective analysis, the investigation was limited to data already collected. Not all procedures and tests were uniform across the cohorts. The follow-up time was shorter and number of dementia outcomes was less in individuals with MCR in EAS. However, both the median and range of follow-up for individuals with MCR criteria in the other two cohorts was long. We corroborated the dementia findings also with incident AD as the outcome; however, other dementia subtypes were not present in sufficient numbers to examine as outcomes.

Clinicians who diagnose patients with MCR in clinical settings can ask questions about the severity of cognitive complaints to help prognostication and to guide management. Furthermore, it is useful for clinicians to know that once patients meet MCR criteria, slowness of gait, a prominent feature of this pre-dementia syndrome, is no longer a predictor of transition to dementia. This observation is in contrast to non-MCR cases where slow gait is a predictor of dementia. In research settings, where more extensive cognitive assessments are done, objective deficits on cognitive testing in patients with MCR can help identify those at highest risk of transitioning to dementia to conduct further investigations or to target for therapeutic trials.

Research in context.

Systematic review:

The authors reviewed the literature using traditional (e.g., PubMed) sources and meeting abstracts and presentations. Since Motoric Cognitive Risk syndrome is a recently described pre-dementia syndrome, there is little information about predictors of transition to dementia.

Interpretation:

Our findings led to an identifying cognitive but not motoric status at time of diagnosis of Motoric Cognitive Risk syndrome as the predictor of transition to dementia. This finding is consistent with the conceptualization of Motoric Cognitive Risk syndrome as a cognitive syndrome.

Future directions:

The findings have both clinical and research implications. Clinicians who diagnose patients with Motoric Cognitive Risk syndrome can use the severity of cognitive complaints to help predict transition to dementia and guide management. In research settings where more extensive cognitive assessments are done, objective deficits on cognitive testing in patients with MCR can help identify those at highest risk of transitioning to dementia to conduct biological studies or to target for therapeutic trials.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The research was supported by the National Institute On Aging (NIA) under award number R56AG057548. Funding agencies for the participating cohorts are as follows. The Einstein Aging Study is funded by the NIH/National Institute on Aging grant (PO1 AG03949). The Memory & Aging Project and the Religious Orders study are supported by the NIH/National Institute on Aging grants (P30AG10161, R01AG15819, R01AG17917, R01AG34374, R01AG33678) and the Illinois Department of Public Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: No disclosure to report for any author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Verghese J, Annweiler C, Ayers E, et al. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome: multicountry prevalence and dementia risk. Neurology 2014;83:718–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, Holtzer R. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome and the risk of dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013;68:412–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabin LA, Smart CM, Crane PK, et al. Subjective Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: An Overview of Self-Report Measures Used Across 19 International Research Studies. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 2015;48 Suppl 1:S63–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmand B, Jonker C, Hooijer C, Lindeboom J. Subjective memory complaints may announce dementia. Neurology 1996;46:121–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verghese J, Ambrose AF, Lipton RB, Wang C. Neurological gait abnormalities and risk of falls in older adults. J Neurol 2010;257:392–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verghese J, LeValley A, Hall CB, Katz MJ, Ambrose AF, Lipton RB. Epidemiology of gait disorders in community-residing older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:255–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, Holtzer R, Xue X. Quantitative gait dysfunction and risk of cognitive decline and dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007;78:929–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett DA, Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Schneider JA. Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 2018;64:S161–s189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the religious orders study. Curr Alzheimer Res 2012;9:628–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh-Park M, Holtzer R, Xue X, Verghese J. Conventional and robust quantitative gait norms in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1512–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capistrant BD, Glymour MM, Berkman LF. Assessing mobility difficulties for cross-national comparisons: results from the World Health Organization Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lifton RP. Individual genomes on the horizon. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1235–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wechsler D WMS-R: Wechsler memory scale-revised: manual. San Antonio, Tx: Psychological Corporation, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 1982;140:566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, et al. Decision rules guiding the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in two community-based cohort studies compared to standard practice in a clinic-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology 2006;27:169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.FM L Applications of Item Response Theory to Practical Testing Problems. Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaun Associates, Inc;, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, et al. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology 2002;59:198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thal LJ, Grundman M, Golden R. Alzheimer’s disease: a correlational analysis of the Blessed Information-Memory-Concentration Test and the Mini-Mental State Exam. Neurology 1986;36:262–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perera S, Patel KV, Rosano C, et al. Gait Speed Predicts Incident Disability: A Pooled Analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016;71:63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crystal HA, Dickson D, Davies P, Masur D, Grober E, Lipton RB. The relative frequency of “dementia of unknown etiology” increases with age and is nearly 50% in nonagenarians. Arch Neurol 2000;57:713–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickson DW, Davies P, Bevona C, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis: a common pathological feature of dementia in very old (> or = 80 years of age) humans. Acta Neuropathol 1994;88:212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verghese J, Crystal HA, Dickson DW, Lipton RB. Validity of clinical criteria for the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 1999;53:1974–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen JA, Verghese J, Zwerling JL. Cognition and gait in older people. Maturitas 2016;93:73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snijders AH, van de Warrenburg BP, Giladi N, Bloem BR. Neurological gait disorders in elderly people: clinical approach and classification. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blumen HM, Allali G, Beauchet O, Lipton RB, Verghese J. A Gray Matter Volume Covariance Network Associated with the Motoric Cognitive Risk Syndrome: A Multi-Cohort MRI Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blumen HM, Brown LL, Habeck C, et al. Gray matter volume covariance patterns associated with gait speed in older adults: a multi-cohort MRI study. Brain imaging and behavior 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allali G, Ayers EI, Verghese J. Motoric Cognitive Risk Syndrome Subtypes and Cognitive Profiles. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016;71:378–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]