Abstract

Objective:

Apathy and depression have each been associated with an increased risk of conversion from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to Alzheimer disease (AD).These symptoms often co-occur and the contribution of each to risk of AD is not clear.

Methods:

National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center participants diagnosed with MCI at baseline and followed until development of AD or loss to follow-up (n = 4,932) were included. The risks of developing AD in MCI patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) (apathy only, depression only, or both) were compared to that in those without NPS in a multivariate Cox regression survival analysis adjusting for baseline cognitive impairment, years of smoking, antidepressant use, and AD medication use.

Results:

Thirty-seven percent (N=1713) of MCI patients developed AD (median follow-up 23 months). MCI patients with both apathy and depression had the greatest risk (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.37; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.17–1.61; p < 0.0001; Wald χ2 = 14.70; df=1). Those with apathy only also had a greater risk (HR = 1.24; 95% CI: 1.05 −1.47; p = 0.01; Wald χ2 = 6.22; df=1), but not those with depression only (HR = 1.08; 95% CI: 0.95–1.22; p=0.25; Wald χ2 = 1.30; df=1). Post-hoc analyses suggested depression may exacerbate cognitive decline in MCI patients with apathy (odds ratio = 0.70; 95% CI 0.52–0.95; p = 0.02; Wald χ2 =5.28; df=1), compared to those without apathy.

Conclusion:

MCI patients with apathy alone or both apathy and depression are at a greater risk of developing AD compared to those with no NPS. Interventions targeting apathy and depression may reduce riskof AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, apathy, depression, mild cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

Apathy and depression are two of the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and often co-occur with one another. Although apathy can occur in the context of depression, it can also occur independently and is often underdiagnosed and undertreated.1 Apathy differs from depression. Although some patients demonstrate loss of motivation or pleasure, depression is characterized by low mood and negative cognitions such as guilt, hopelessness, or suicidal ideation.2 In contrast, those with apathy demonstrate reduced emotion and reactiveness when stimulated, in addition to reduced goal-directed activities. In recognition of these differences, diagnostic criteria for apathy have now been proposed.3

Findings from neuroimaging studies in patients with apathy4 and depression,5 and studies that compare apathy and depression,6 report differences in brain structural volumes, brain hypoperfusion, white matter tract integrity, and white matter hyperintensities. Considering that both apathy and depression have also been linked to cognitive decline, they are each associated with different domains of executive functioning, indicating possible differences in frontal lobe pathology.7 Furthermore, patients with MCI with apathy demonstrate a lower capacity to carry out activities of daily living compared with patients with depression, suggesting that apathy may have a greater impact on caregiver burden.8

A number of studies in cognitively normal elderly individuals and patients with MCI have supported apathy and depression as risk factors for conversion to Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Donovan et al.9 reported that only depression, and not apathy, was a significant predictor of disease progression in patients with MCI. Vicini Chilovi et al.10 and Palmer et al.11 reported that apathy was a significant risk factor for conversion to AD. However, Vicini Chilovi et al.10 reported that depression without apathy was associated with reduced risk of conversion to AD, whereas

Palmer et al.11 reported that depression did not increase risk of AD. These studies had relatively small sample sizes, with variability in how both depression and apathy were assessed that may have contributed to the conflicting findings. Additional studies with larger sample sizes and standardized assessments are needed to elucidate whether these NPS have an overlapping or additive impact on risk of conversion from MCI to AD.

We therefore wish to determine, in a larger analysis than previously completed, the relative contributions of apathy and depression to the risk of conversion from MCI to AD. We hypothesized that apathy and depression would both individually be associated with increased risk of AD, whereas apathy and depression combined would be associated with a greater risk than either alone.

METHODS

Study Sample

The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database includes data collected annually from past and present Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs) in the United States. Enrolled participants undergo a physical assessment, in addition to standardized clinical and neuropsychological assessments. Participants may also volunteer to provide imaging and laboratory specimens at specific ADCs. In September 2005, the NACC implemented the uniform dataset (UDS) at all ADCs, which collects longitudinal data prospectively, using standardized clinical evaluations. This article includes data from UDS visits conducted between September 2005 and February 2018. Participants undergo an annual assessment, and information on demographics, neuropsychological testing, and clinical diagnoses are obtained at each visit. Although all participants range in cognitive status (cognitively normal, MCI, or dementia), for the purposes of this article, we included participants with a diagnosis of MCI at baseline, and who had one or more follow-up UDS visits.

Classification of Apathy and Depression

The subject health history (UDS Form A5) is completed by a clinician or ADC staff based on participant or co-participant report. Apathy and depression are separate items on UDS Form A5, and are characterized as present, absent, or unknown. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Questionnaire (NPI-Q) is a behavioral assessment completed by the clinician or other trained health professional and includes an assessment of 12 behaviors: delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, depression/dysphoria, anxiety, elation/euphoria, disinhibition, irritability/lability, motor disturbance, nighttime behaviors, and appetite/eating. If an NPS is present, the severity of the symptom is rated as 1) mild; 2) moderate; or 3) severe. We identified clinically significant apathy and/or depression as either moderate (score = 2) or severe (score = 3) on the NPI-Q12 (UDS Form B5). Participants did not have any clinically significant NPS at baseline if each of their NPS were rated as absent, or of mild severity on the NPI-Q (UDS Form B5). Depression was also determined by clinical diagnosis that may include Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’ criteria for major depressive disorder (UDS Form D1). Finally, a score of 5 or greater on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was identified as clinically significant depressive symptoms (UDS Form B6).13 Participants with neither apathy nor depression, and who had other clinically significant NPS were excluded.

Classification of AD Diagnosis

A consensus team or physician diagnosed dementia using the results of a structured clinical history, neuropsychology testing, and validated assessments of symptoms and function. Dementia of the AD type was diagnosed according to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria prior to 2015,14 and the National Institute on Aging/Alzheimer’s Association criteria15 after 2015. Participants were also identified as having an AD diagnosis, if AD was the primary or contributing cause of cognitive impairment, which included participants who had either probable or possible dementia of the AD type. The accuracy of the clinical diagnoses of AD in the NACC dataset has been validated with neuropathological criteria for AD.16

Medication and Medical Illness History

Antidepressant, antipsychotic, anxiolytic, and AD medication

A category for U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for AD symptoms was reviewed; this included current use of memantine and cholinesterase inhibitors. A category of prescribed antidepressants was also examined, which included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, serotonin-norepi-nephrine reuptake inhibitors, phenylpiperazine, tetracyclic, and miscellaneous antidepressants. Current use of antipsychotic and anxiolytic medications were also examined. Antipsychotics included atypical antipsychotics, miscellaneous antipsychotics, psychotherapeutic combinations, phenothiazine psychotics, and thioxanthenes. Anxiolytics included barbiturates, benzodiazepines, sedative, hypnotics, and miscellaneous anxiolytics.

Medical Condition and Health Behaviors

A structured health history form was used to collect medical conditions associated with depression and AD. This form was based on reports from the subject or coparticipant. A medical condition was considered present if it was recent/active or remote/inactive. Medical conditions included were heart attack/ cardiac arrest, atrial fibrillation, stroke, transient ischemic attack, diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. The health history form was also used to collect information regarding alcohol abuse. Participants were considered to have alcohol abuse if they reported recent/active or remote/inactive clinically significant impairment over a 12-month period demonstrated in one of the following areas: work, driving, legal, or social. Participants were also asked the total number of years they smoked cigarettes.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline demographics, medication history, and assessments were compared between patients with apathy only, depression only, apathy and depression, and no clinically significant NPS. Bivariate survival analyses were conducted with demographics, medical conditions, health behaviors, medication use, and APOE E4 allele variables to determine predictors associated with an increased risk of conversion to AD. Significant predictors from bivariate analyses were assessed for multicollinearity and included as covariates in the multivariate Cox regression.

Post-hoc analyses were conducted to further investigate the effect of apathy, depression, and both apathy and depression on AD conversion. Specifically, a binary logistic regression was computed to determine the odds of apathy, depression, and apathy x depression interaction term, in predicting conversion to AD from MCI. Subgroup analyses were then conducted within individuals who had and did not have apathy to determine whether depression increased the odds of conversion to AD from MCI. In all post-hoc analyses, significant predictors from previously conducted bivariate analyses were included as covariates.

RESULTS

This analysis included 4,932 participants with MCI (mean ± standard deviation age = 73.2 ± 9.2; Mini-Mental State Examination = 27.1 ± 2.5; 50% [N = 2,482] male; and 35% [N = 1,713] participants that converted to AD). Of these participants, 8% had apathy only, 31% had depression only, 14% had apathy and depression, and 48% had no NPS. Participants who did not have clinically significant apathy and/or depression, and who had other clinically significant NPS were excluded from analyses (N = 377). Baseline clinical characteristics based on NPS group are included in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and Medical History of Study Participants at Baseline

| Apathy Only N=388 |

Depression Only N=1514 |

Apathy + Depression N=686 |

No NPS N=2344 |

Test Statistic and Degrees of Freedom: χ2(df) or F(df) |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 73.9 (8.6) | 71.5(9.3) | 70.8 (9.3) | 74.9 (8.8) | F(3,4931) = 60.9 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male, %) | 266 (68.6) | 606 (40.0) | 389 (56.7) | 1221 (52.1) | Χ2(3) = 129.9 | <0.001 |

| Education (mean, SD) | 15.4(3.2) | 15.3(3.4) | 15.3(3.3) | 15.3(3.3) | F(3,4914) = 0.2 | 0.90 |

| MMSE (mean, SD) | 26.7(2.6) | 27.3 (2.4) | 27.0(2.6) | 27.2 (2.5) | F(3,4501) = 7.4 | <0.001 |

| Antidepressants (yes, %) | 47(12.2) | 819 (54.5) | 384 (56.2) | 181 (7.8) | χ2(3)= 1272.6 | <0.001 |

| Antipsychotic (yes, %) | 0 (0.0) | 51 (3.4) | 30 (4.4) | 10 (0.4) | χ2(3) = 76.6 | <0.001 |

| Anxiolytics (yes, %) | 45(11.7) | 277 (18.4) | 123(18.0) | 159(6.8) | χ2(3)= 136.6 | <0.001 |

| AD medications (yes, %) | 122(31.8) | 366 (24.3) | 216(31.6) | 461 (19.8) | Χ2(3) = 56.8 | <0.001 |

| Heart attack (ever, %) | 27 (7.0) | 86 (5.7) | 38 (5.6) | 152(6.5) | χ2(3) 1.9 | 0.60 |

| Atrial fibrillation (ever, %) | 25 (6.5) | 120 (8.0) | 47 (6.9) | 188(8.1) | χ2(3) 2.0 | 0.58 |

| Stroke (ever, %) | 20 (5.2) | 95 (6.3) | 44 (6.5) | 125 (5.3) | χ2(3) 2.4 | 0.50 |

| TIA (ever, %) | 25 (6.5) | 78 (5.2) | 36 (5.3) | 128 (5.5) | χ2(3) 1.0 | 0.80 |

| Hypertension (ever, %) | 216(55.7) | 827 (54.8) | 391 (57.2) | 1253 (53.7) | Χ2(3) = 2.8 | 0.42 |

| Diabetes (ever, %) | 65 (16.9) | 233 (15.4) | 106(15.5) | 325 (13.9) | χ2(3) 3.4 | 0.33 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (ever, %) | 223 (57.9) | 827 (55.3) | 391 (57.5) | 1255 (54.2) | χ2(3) 3.6 | 0.31 |

| Smoking (years, mean, SD) | 12.47 (21.0) | 14.61 (23.1) | 13.87 (21.8) | 12.37 (20.4) | F(3,4915) = 3.7 | 0.01 |

| Alcohol abuse (ever, %) | 18(4.7) | 128 (8.5) | 56 (8.2) | 77 (3.3) | χ2(3) I 55.8 | <0.001 |

| APOE4 allele (N, %) | 144(42.7) | 546(44.1) | 240 (42.6) | 813(41.1) | Χ2(3) = 2.9 | 0.42 |

Notes: One-way analysis of variance for continuousvariables and the χ2test for categorical variables.df: degrees of freedom; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; SD: standard deviation; TIA: transient ischemic attack.

Selection of Covariates

Bivariate survival analyses were conducted to determine which clinical characteristics were associated with increased risk of conversion to AD (Table 2). Clinical variables that remained significantly associated with AD included Mini-Mental State Examination, years of smoking, antidepressant use, and AD medication use. These variables were then assessed for multicollinearity and were determined to not be collinear with one another (variance inflation factor cutoff <2.5). As such, all significant predictors were entered into a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model.

TABLE 2.

Hazard Ratios for Development of AD for Each Predictor Variable in Bivariate Analyses

| Predictor Variable | N | Hazard Ratios (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | df, p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 4,932 | 1.00(0.99–1.00) | 1.47 | 1, 0.23 |

| Sex (male compared to female) | 4,932 | 1.06(0.97–1.17) | 1.66 | 1, 0.20 |

| Education (years) | 4,915 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 2.04 | 1, 0.15 |

| MMSE | 4,502 | 0.91 (0.89–0.92)b | 115.63 | 1, <0.001 |

| Medical Conditions (Presence versus Absence) | ||||

| Diabetes | 4,915 | 1.01 (0.87–1.16) | 0.01 | 1, 0.91 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 4,878 | 0.98(0.89–1.07) | ||

| Hypertension | 4,917 | 0.98(0.89–1.07) | 0.24 | 1, 0.62 |

| Heart attack | 4,921 | 0.99(0.81–1.21) | 0.004 | 1, 0.95 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4,910 | 1.04(0.88–1.25) | 0.02 | 1, 0.63 |

| Stroke | 4,914 | 1.01 (0.82–1.25) | 0.01 | 1, 0.92 |

| TIA | 4,880 | 0.99(0.80–1.21) | 0.02 | 1, 0.89 |

| Health Behaviors | ||||

| Smoking (years) | 4,919 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01)a | 7.56 | 1, 0.006 |

| Alcohol abuse (presence versus absence) | 4,919 | 1.03 (0.82–1.28) | 0.05 | 1, 0.82 |

| Medications (Use versus No Use) | ||||

| Antidepressants | 4,894 | 1.20 (1.08–1.33)b | 11.02 | 1, 0.001 |

| Antipsychotics | 4,894 | 1.26(0.80–1.98) | 1.001 | 1, 0.32 |

| Anxiolytic | 4,894 | 0.98(0.83–1.15) | 0.07 | 1, 0.79 |

| AD medications | 4,894 | 1.50 (1.36–1.65)b | 63.29 | 1, <0.001 |

| Other Risk Factors | ||||

| APOE4 allele (presence versus not) | 4,117 | 1.06(0.96–1.17) | 1.19 | 1, 0.28 |

CI: confidence interval; df: degrees of freedom; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; TIA: transient ischemic attack.

p<0.05.

p<0.001.

Main Outcome

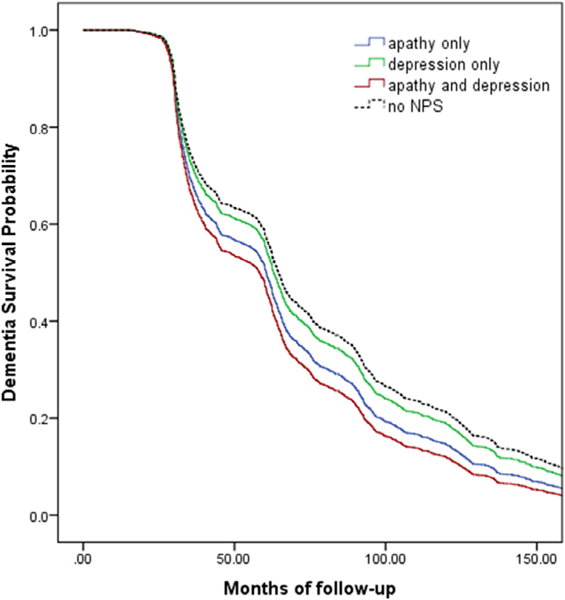

After adjusting for the previous predictors, participants with MCI with both apathy and depression had the greatest risk of conversion to AD. However, participants with MCI with apathy only also had a significantly greater risk of conversion to AD compared with patients with no NPS (Fig. 1, Table 3). Participants with MCI with depression only did not have a significantly greater risk of conversion to AD compared with patients with no NPS. Visual inspection of Kaplan-Meier curves indicated that the proportional hazards assumption was not violated.

FIGURE 1.

Survival to development of AD based on the presence of apathy only, depression only, apathy and depression, or no NPS, at baseline.

TABLE 3.

Hazard Ratios for Development of AD for Each Predictor Variable in Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazard Survival Analyses

| Predictor Variables | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | df, p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apathy only | 1.24(1.05–1.47)a | 6.22 | 1, 0.013 |

| Depression only | 1.08 (0.95–1.22) | 1.30 | 1, 0.25 |

| Apathy and depression | 1.37(1.17–1.61)b | 14.70 | 1, <0.001 |

| Neither apathy nor depression (ref) | – | – | – |

| MMSE score | 0.91 (0.89–0.93)b | 104.70 | 1, <0.001 |

| Years of smoking | 1.003 (1.00–1.01)a | 8.98 | 1, 0.003 |

| Antidepressant use | 1.04 (0.92–1.18) | 0.46 | 1, 0.50 |

| No antidepressant use (ref) | – | – | – |

| AD medication use | 1.42 (1.28–1.58)b | 43.41 | 1, <0.001 |

| No AD medication use (ref) | – | – | – |

CI: confidence interval; df: degrees of freedom; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; ref: reference group.

p<0.05.

p<0.001.

Post-Hoc Analyses

After adjusting for predictors, the presence of apathy, and apathy x depression, were significantly associated with an increased odds of conversion to AD in participants with MCI. The presence of depression only in participants with MCI did not significantly increase the odds of conversion to AD (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Odds Ratios for Development of AD for Each Predictor Variable in Binary Logistic Regression

| Predictor Variables | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | df, p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apathy only | 1.48 (1.16–1.88)a | 10.02 | 1, 0.002 |

| Depression only | 1.09 (0.92–1.23) | 1.07 | 1, 0.30 |

| Apathy by depression | 0.66 (0.48–0.91)a | 6.60 | 1, 0.01 |

| MMSE score | 0.84 (0.82–0.86)b | 165.64 | 1, <0.001 |

| Years of smoking | 0.998(0.995–1.001) | 1.63 | 0.20 |

| Antidepressant use | 0.85 (0.72–1.01) | 3.50 | 0.06 |

| No antidepressant use (ref) | – | – | – |

| AD medication use | 2.89 (2.49–3.34)b | 199.06 | 1, <0.001 |

| No AD medication use (ref) | – | ||

CI: confidence interval; df: degrees of freedom; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; ref: reference group.

p<0.05.

p<0.001.

Subsequent subgroup analyses indicated that the apathy x depression interaction term was significant such that in participants with MCI who had apathy, the presence of depression was significantly associated with conversion to AD, whereas the presence of depression in participants with MCI who did not have apathy was not associated with conversion to AD (Tables 5, 6).

TABLE 5.

Odds Ratios for Development of AD for Each Predictor Variable in Binary Logistic Regression in MCI Patients With Apathy

| Predictor Variables | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | df, p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression only | 0.70 (0.52–0.95)a | 5.28 | 1, 0.02 |

| MMSE score | 0.86 (0.82–0.91)b | 27.91 | 1, <0.001 |

| Years of smoking | 1.001 (0.995–1.01) | 0.19 | 1, 0.67 |

| Antidepressant use | 0.91 (0.67–1.23) | 0.36 | 1, 0.55 |

| No antidepressant use (ref) | – | – | – |

| AD medication use | 2.52 (1.90–3.35)b | 40.56 | 1, <0.001 |

| No AD medication use (ref) | – | – | – |

CI: confidence interval; df: degrees of freedom; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; ref: reference group.

p<0.05.

p<0.001.

TABLE 6.

Odds Ratios for Development of AD for Each Predictor Variable in Binary Logistic Regression in MCI Patients With No Apathy

| Predictor Variables | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | df, p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression only | 1.11 (0.93–1.32) | 1.31 | 1, 0.25 |

| MMSE score | 0.83 (0.80–0.86)a | 138.64 | 1, <0.001 |

| Years of smoking | 0.997 (0.994–1.001) | 2.67 | 1, 0.10 |

| Antidepressant use | 0.83 (0.68–1.01) | 3.42 | 1, 0.06 |

| No antidepressant use (ref) | – | – | – |

| AD medication use | 3.02 (2.55–3.59)a | 159.22 | 1, <0.001 |

| No AD medication use (ref) | – | – | – |

CI: confidence interval; df: degrees of freedom; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; ref: reference group.

p<0.001.

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal study, we report that patients with MCI with both apathy and depression have a significantly greater risk of conversion to AD compared with patients with MCI with no NPS, and that this risk is greater compared with patients with MCI with apathy, or depression only. Post-hoc analyses suggest that this may be due to depression exacerbating cognitive decline in patients with apathy.

Interestingly, we report that depression in the absence of clinically significant apathy in MCI was not associated with a greater risk of AD conversion compared with the presence of no NPS. Although previous studies report that a history of depression in elderly individuals and patients with MCI is a significant risk factor for AD conversion,17 apathy was not considered separately. Longitudinal-cohort studies have reported that apathy and depression are two of the most common and persistent NPS in patients with MCI, occurring in approximately 15% and 20%, respectively.12 Because of their high prevalence, apathy and depression are likely to co-occur with one another. As such, the impact of apathy should be taken into account when investigating depression as a risk factor for AD conversion.

Underlying AD pathology may be responsible for the additive risk associated with the presence of both apathy and depression in patients with MCI. Specifically, neuropathological, neuroimaging, and neurochemical studies in patients with MCI and AD have reported that AD pathophysiology,18,19 brain hypo-metabolism,20,21 and changes in neurotransmitter systems22,23 are associated with the presence of apathy and depression, independently. These pathologies have also been associated with an increased risk of conversion to AD, and increased AD severity. Therefore, the presence of apathy or depression in patients with MCI may increase the risk of AD conversion through AD pathology, and the increased risk associated with the presence of both symptoms may be because of the combined pathological burden.

In a pharmacological challenge study with dextroamphetamine in AD patients with apathy, apathy was associated with a blunted behavioral response to dextroamphetamine, suggesting that apathy may be associated with an impaired dopaminergic (DA) brain reward system.24 Following this study, in a small clinical trial with the psychostimulant methylphenidate, Herrmann et al.25 reported that DA changes predicted therapeutic response, further supporting a link between the DA system and apathy. Interestingly, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been reported to worsen apathy in some patients with depressive symptoms.26 As such, although the DA brain reward system may be associated with apathy, changes in the serotonergic system in patients that exhibit depressive symptoms may exacerbate symptoms of apathy.

Our findings identified that years of smoking was associated with an increased risk of conversion to AD. A number of studies have demonstrated that smoking is associated with the presence of AD patho-physiology27 and oxidative stress.28 Furthermore, as greater oxidative stress has been shown to exacerbate AD pathology,29 smoking may increase the risk of AD conversion through increasing oxidative stress. In this study, the lack of significant associations between other cardiovascular risk factors and risk of conversion to AD contradicts other studies that have reported that diabetes,30 history of heart attack,31 and the presence of an APOE 4 allele32 increases the risk of AD conversion. However, this may be due to our study sample, in which these risk factors had similar rates of occurrence between patients with MCI with apathy, depression, both apathy and depression, and no NPS.

In our sample we found that antidepressant use was not associated with risk of AD conversion. There are some studies that indicate a protective effect for antidepressants, but findings have been inconsistent. Specifically, antidepressants for the treatment of depression have demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties that may be beneficial in reducing AD-related proinflammatory processes and pathology.33 Conversely, some lines of evidence have suggested that in certain instances antidepressants could increase apathy,34,35 which may be associated with increased risk. Interestingly, in our study sample, approximately 20% of patients with MCI (12% apathy only, 8% no NPS) were prescribed an antidepressant despite not having a past or current diagnosis of depression. These patients may have been prescribed antidepressants for reasons other than depression such as anxiety, insomnia, or anorexia. It is also possible that patients with apathy were misdiagnosed as having depression, or were treated by a physician who chose to treat their apathy with an antidepressant. Unfortunately, as data prior to NACC enrollment are not available, we were unable to study this finding further.

Initial between-group comparisons indicated that patients with MCI with apathy, depression, or both NPS were more often treated with an AD medication compared with patients with MCI with no NPS. The frequency of this medication use may be considered high given the lack of evidence supporting a significant benefit of cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) on cognition in patients with MCI,36 and on NPS in patients with MCI and AD.37 Support for their lack of efficacy is further substantiated by our findings as we report that AD medication use was associated with an increased risk of conversion to AD. This finding does not necessarily mean that these medications worsened cognition, but rather did not prevent conversion to AD in a subgroup of patients considered to be high risk. However, the rates of AD medication use reported reflect current prescription practices in the United States of ChEIs in this patient population.38 It is also possible that ChEIs were prescribed for the treatment of apathy. Previous randomized controlled trials with ChEIs have demonstrated a small benefit for apathy in patients with AD.39 However, because these studies did not actively recruit patients with apathy, their efficacy on clinically significant apathy is unclear.

Study strengths included a large sample of participants, providing sufficient power to detect between-group differences and predictors of AD conversion. This dataset was also well-characterized, which included AD diagnoses that were completed by experienced clinicians in specialized memory-clinic settings. The inclusion of NPI-Q severity scores allowed us to identify patients who had clinically significant NPS in addition to inclusion of other measures of NPS. Despite several study strengths, these results must also be reviewed in the context of study limitations. The sample included in this analysis may not be considered representative of the general population because patients were attending specialist memory clinics. Another limitation was that depression was not diagnosed with a standardized interview, although assessments were completed by experienced clinicians and informed by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’ criteria. In addition, the diagnosis of apathy was not completed with an apathy-specific scale, such as the Apathy Evaluation Scale, which would have allowed us to investigate subdomains of apathy (e.g., behavior, cognition, and emotional domains).40 However, the assessment of apathy was completed by experienced clinicians as part of a structured assessment. Finally, we did not have data regarding age of first onset of NPS or biomarker data that may have allowed us to disentangle whether NPS caused, exacerbated, or occurred as a consequence of AD pathology.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our findings indicate that patients with MCI with either apathy alone or apathy and depression are at a significantly greater risk of conversion to AD compared with patients with no NPS. Future studies focusing on the early detection and treatment of apathy and depression in patients with MCI should be explored to determine if this can reduce risk of AD.

The NACC database is funded by a National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, M.D.), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, M.D.), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, M.D.), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, M.D., Ph.D.), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, M.D., Ph.D.), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, Psy.D.), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, Ph.D.), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, M.D., Ph.D.), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, M.D., Ph.D.), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, Ph.D.), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, M.D.), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, M.D.), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, M.D.), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, M. D.), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, M.D., M. S.), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, M.D.), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, Ph.D.), P50 AG005131 (PI James Brewer, M.D., Ph.D.), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, M.D.), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swer-dlow, M.D.), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, Ph. D.), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, M.D., Ph.D.), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, M.D., Ph.D.), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, M.D.), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, M.D.), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, M.D.), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, Ph.D.), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, M.D.), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, M.D., F.R. C.P.), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, M.D.), and P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, M.D., Ph.D.)

KLL has received research grants from the National Institute of Aging, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Fund, the Alzheimer Society of Canada, Alzheimer’s Association, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Brain Canada, AbbVie, Lundbeck, and Axovant Sciences Ltd., and has received honoraria from AbbVie, Otsuka, and Lundbeck. MR is funded by a CIHR Doctoral Research Award (the Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarships Doctoral Award). NH has received research grants from the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Fund, the Alzheimer Society of Canada, the National Institute of Health Research, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Brain Canada, Alzheimer’s Association, Lundbeck, Axo-vant Sciences Ltd., and Roche, and consultation fees from Lilly, Merck, and Astellas. For the remaining authors none were declared.

References

- 1.Marin RS, Firinciogullari S, Biedrzycki RC: Group differences in the relationship between apathy and depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 1994; 182:235–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy ML, Cummings JL, Fairbanks LA, et al. : Apathy is not depres-sion.J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:314–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robert P, Lanctot KL, Aguera-Ortiz L, et al. : Is it time to revise the diagnostic criteria for apathy in brain disorders? The 2018 international consensus group. Eur Psychiatry 2018; 54:71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apostolova LG, Akopyan GG, Partiali N, et al. : Structural correlates of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2007; 24:91–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holthoff VA, Beuthien-Baumann B, Pietrzyk U, et al. : [Changes in regional cerebral perfusion in depression.SPECT monitoring of response to treatment]. Nervenarzt 1999; 70:620–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starkstein SE, Mizrahi R, Capizzano AA, et al. : Neuroimaging correlates of apathy and depression in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009; 21:259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakaaki S, Murata Y, Sato J, et al. : Association between apathy/ depression and executive function in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 2008; 20:964–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zahodne LB, Tremont G: Unique effects of apathy and depression signs on cognition and function in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 28:50–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donovan NJ, Amariglio RE, Zoller AS, et al. : Subjective cognitive concerns and neuropsychiatric predictors of progression to the early clinical stages of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014; 22:1642–1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chilovi Vicini B, Conti M, Zanetti M, et al. : Differential impact of apathy and depression in the development of dementia in mild cognitive impairment patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2009; 27:390–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmer K, Di Iulio F, Varsi AE, et al. : Neuropsychiatric predictors of progression from amnestic-mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: the role of depression and apathy. J Alzheimers Dis 2010; 20:175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, et al. : Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA 2002; 288:1475–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg SA: How to try this: the Geriatric Depression Scale: Short Form. Am J Nurs 2007; 107:60–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. : Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984; 34:939–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. : The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011; 7:263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beach TG, Monsell SE, Phillips LE, et al. : Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005–2010. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2012; 71:266–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessing LV: Depression and the risk for dementia. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012; 25:457–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mori T, Shimada H, Shinotoh H, et al. : Apathy correlates with pre-frontal amyloid beta deposition in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014; 85:449–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrington KD, Lim YY, Gould E, et al. : Amyloid-beta and depression in healthy older adults: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2015; 49:36–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delrieu J, Desmidt T, Camus V, et al. : Apathy as a feature of prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: an FDG-PET ADNI study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015; 30:470–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krell-Roesch J, Ruider H, Lowe VJ, et al. : FDG-PET and neuropsychiatric symptoms among cognitively normal elderly persons: the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. J Alzheimers Dis 2016; 53:1609–1616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chong TT, Husain M: The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology and treatment of apathy. Prog Brain Res 2016; 229:389–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fakhoury M: Revisiting the serotonin hypothesis: implications for major depressive disorders. Mol Neurobiol 2016; 53:2778–2786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, Black SE, et al. : Apathy associated with Alzheimer disease: use of dextroamphetamine challenge. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008; 16:551–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrmann N, Rothenburg LS, Black SE, et al. : Methylphenidate for the treatment of apathy in Alzheimer disease: prediction of response using dextroamphetamine challenge. J Clin Psycho-pharmacol 2008; 28:296–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sansone RA, Sansone LA: SSRI-induced indifference. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2010; 7:14–18 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durazzo TC, Mattsson N, Weiner MW, et al. : Interaction of cigarette smoking history with APOE genotype and age on amyloid level, glucose metabolism, and neurocognition in cognitively normal elders. Nicotine Tob Res 2016; 18:204–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isik B, Ceylan A, Isik R: Oxidative stress in smokers and nonsmokers. Inhal Toxicol 2007; 19:767–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang WJ, Zhang X, Chen WW: Role of oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed Rep 2016; 4:519–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu WL, von Strauss E, Qiu CX, et al. : Uncontrolled diabetes increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a population-based cohort study. Diabetologia 2009; 52:1031–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jefferson AL, Beiser AS, Himali JJ, et al. : Low cardiac index is associated with incident dementia and Alzheimer disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2015; 131:1333–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, et al. : Gene dose of apo-lipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science 1993; 261:921–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hannestad J, DellaGioia N, Bloch M: The effect of antidepressant medication treatment on serum levels of inflammatory cytokines: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011; 36: 2452–2459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodwin GM, Price J, De Bodinat C, et al. : Emotional blunting with antidepressant treatments: a survey among depressed patients. J Affect Disord 2017; 221:31–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothschild AJ, Raskin J, Wang CN, et al. : The relationship between change in apathy and changes in cognition and functional outcomes in currently non-depressed SSRI-treated patients with major depressive disorder. Compr Psychiatry 2014; 55:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sobow T, Kloszewska I: Cholinesterase inhibitors in mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurol Neurochir Pol 2007; 41:13–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trinh NH, Hoblyn J, Mohanty S, et al. : Efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional impairment in Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2003; 289:210–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mucha L, Shaohung S, Cuffel B, et al. : Comparison of cholinesterase inhibitor utilization patterns and associated health care costs in Alzheimer’s disease. J Manag Care Pharm 2008; 14:451–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruthirakuhan MT, Herrmann N, Abraham EH, et al. : Pharmacological interventions for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 5:CD012197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guercio BJ, Donovan NJ Munro CE, et al. : The Apathy Evaluation Scale: acomparison of subject, informant, and clinician report in cognitively normal elderly and mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 2015; 47:421–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]