Abstract

Objective

The objective of this research was to develop a principles framework to guide action on Māori/Indigenous homelessness in Aotearoa incorporating Rangatiratanga (Māori self-determination), Whānau Ora (Government policy that places Māori families at the center of funding, policy and services) and Housing First.

Method

Three pathways were identified as creating opportunities for action on Māori homelessness: Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi is the Māori self-determination pathway; Whānau Ora, a government-sponsored policy supports whānau/family as the pathway for Māori wellbeing and disparities reduction; and Housing First, an international pathway with local application for homelessness that is being implemented in parts of Aotearoa. The potential opportunities of the three pathways shaped interviews with authoritative Māori about Māori principles (derived from the three pathways) for addressing Māori homelessness. Twenty interviews were conducted with Māori experts using Kaupapa Māori research processes, eliciting advice about addressing Māori homelessness. A principles framework called Whare Ōranga was developed to synthesise these views.

Results

Addressing Māori homelessness must be anchored in rights-based and culturally aligned practice empowered by Māori worldviews, principles and processes. Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which endorses Māori tribal self-determination and authority, and Whānau Ora as a government obligation to reduce inequities in Māori homelessness, are the foundations for such action. Colonisation and historical trauma are root causes of Māori homelessness. Strong rights-based frameworks are needed to enact decolonisation and guide policy. These frameworks exist in Tino Rangatiratanga/Māori self-determination and Whānau Ora.

Conclusion

Whare Ōranga: An Indigenous Housing Interventions Principles Framework was developed in Aotearoa/New Zealand to end Māori homelessness. Future research is needed on the practical application of this framework in ending Māori homelessness. Moreover, the use value of the Whare Ōranga Framework as a workable approach to ending homelessness in other indigenous populations is yet to be considered.

Keywords: Housing first, Homelessness, Indigenous, Māori, Treaty of waitangi, Whānau ora, Kaupapa māori, Colonisation, Wellbeing

Highlights

-

•

Whare Ōranga: An Indigenous Housing Interventions Principles Framework was developed in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

-

•

Addressing Māori homelessness must be anchored in rights-based and culturally aligned practice empowered by Māori worldviews.</span>

-

•

Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and Whānau Ora as a government obligation to reduce inequities, are the foundations for action.

1. Introduction

Aotearoa1 has a relatively strong, albeit imperfect, legislative and institutional framework2 for addressing the historical wrongs and contemporary effects of colonisation (Orange, 2015). For this reason, New Zealand is an excellent place to test an indigenous lens on applying international solutions to problems that disproportionately affect indigenous peoples. Māori are four times more likely to be homeless than New Zealanders of European descent/Pākehā (Kate Amore, 2016). Currently one percent of New Zealanders are homeless, and “homelessness is worsening in New Zealand in both numbers and as a proportion of the population”(Kate Amore, 2016, p. 7). This upward trend accelerated between the 2006 and 2013 censuses, more so for Māori than for NZ European/Pākēha (Kate Amore, 2016). In 2013, 12,754 Māori were homeless, comprising 32% of the homeless population compared to comprising just 14.9% of the total population (Kate Amore, 2016). This paper places a Māori lens on homelessness in Aotearoa/New Zealand by developing a principles framework to inform homelessness interventions for Māori incorporating Tino Rangatiratanga (Māori sovereignty and self detemination), Whānau Ora (governmental policy of whānau (family) centered services) and Housing First.

1.1. Background

Inequities in homelessness fit into a context in which a number of interlinked inequities disproportionately affect Māori (Poata-Smith, 2013), across many domains including health (Harris et al., 2006) and housing (A. Johnson, Howden-Chapman, & Eaqub, 2018). Historical policies that alienated Māori from land, and made it difficult for Māori to access home ownership have ongoing inter-generational ramifications (Bierre, 2009). Entrenched Western legal assumptions continue to make it very difficult for Māori to build housing on communally-owned land (Ruru, 2017b), and Māori have far lower rates of home ownership than NZ Europeans, at 28% and 57% respectively (A. Johnson et al., 2018).

Inequities for Māori are primarily explained by the effects of colonisation. Te Tiriti o Waitangi expedited the process of colonisation by paving the way for the usurpation of Māori sovereignty, and is upheld as a central founding document of Aotearoa/New Zealand (Orange, 2015). The English version of Te Tiriti ceded sovereignty to the British Crown, the Māori version ceded British governance (over British subjects) while securing Māori tribal sovereignty. The differences in the English language and Māori language versions of Te Tiriti o Waitangi are a source of contention about the legitimacy of the Treaty as a colonial instrument, manifesting contemporarily through the government's approach to Te Tiriti principles of partnership, participation and protection, and through an as yet unrealised right to sovereignty (Tino rangatiratanga) for Iwi and Māori. The opportunities afforded by Te Tiriti settlements potentially render Iwi and rūnanga key players in housing homeless Māori. Both government and Iwi have a role to play in addressing Māori homelessness.

Homelessness is anchored for Māori in the enduring effects of colonisation and historical trauma. Aboriginal researcher Laws states “when you look at the consequences and impacts of the historical trauma and the ongoing effects, it puts Aboriginal homelessness in 2016 in a new perspective” (Laws, 2016, p. 30). Similarly, Bingham et al. found that pathways into homelessness were different for Indigenous Canadians compared to non-indigenous (Bingham et al., 2019). They argue that the ongoing effects of colonisation and trauma are responsible for the pathways into homelessness for indigenous peoples, and that existing homelessness and health services do not adequately address these root causes. Existing homelessness interventions in New Zealand tend towards an individualised approach, at the expense of more collectively-oriented interventions. Collectively-oriented indigenous solutions and cultural values such as whānaungatanga (collectivism) and Papakāinga – Māori builds on Māori land (Ruru, 2017a), are foundational and critical to solutions for Māori homelessness, and potentially enable a move towards decolonisation.

Poor living conditions, economic struggles, stress, stigma, and social exclusion associated with homelessness affect physical, psychological, emotional, and social well-being (Hodgetts, Radley, Chamberlain, & Hodgetts, 2007). As identified by Bingham et al. (2019), mutliple pathways into homelessness that may differ for different groups, require multiple solutions that attend to the individual as well as a more collective approach where appropriate. Understanding the role of historical trauma requires a holistic understanding of the network of influences upon a person or a community that render some affected by adversity, and others resilient. As pointed out in indigenous trauma literature, “cultural protective factors buffer the negative effects of traumatic events on our wellness” (Walters, 2006, p. 29).

The New Zealand Government defines homelessness as individuals having no options to acquire safe and secure housing: are without shelter, in temporary accommodation, sharing accommodation with a household or living in uninhabitable housing (Statistics New Zealand, 2009). Amore et al. reviewed this definition, extending it to include multiple dimensions of habitability (K Amore, Viggers, Baker, & Howden-Chapman, 2013). Both of these definitions are intended to apply at a population-wide level and so do not fully account for indigenous perspectives on homelessness. Indigenous definitions of homelessness tend to include aspects of connection and relationship. The Definition of Indigenous Homelessness in Canada for example includes “individuals, families and communities isolated from their relationship to land, water, place, family, kin, each other, animals, cultures, languages and identities” (Thistle, 2012). Similarly, Paul Memmott's concept of ‘spiritual homelessness’ describes Indigenous Australians who are homeless in the mainstream sense, but who also are disconnected from kin and country (Memmott, 2015). This definition recognises that the concept of ‘home’ has different meanings for Indigenous Australians than for those of European descent. Interventions that assume a Western definition of homelessness may continue a pattern of disconnection by failing to address these wider aspects of homelessness.

Colonisation and the breakdown of cultural support means there are many Māori with no active connection to their whānau. Durie's classification of whānau for whom cultural knowledge was lost led them to states of disorganisation (whānau wetewete); whānau who lack respect for each other (whānau tūkino); restricted families (whānau pōhara) who are well intentioned but often lack the resources to take action to realise their aspirations and hopes, and isolated whānau (whānau tū-mokemoke) who are alienated from Māori networks (Durie, 1997). They struggle to reclaim knowledge of who they are (Lawson-Te Aho, 2010). Sadly, Māori principles and values like whanaungatanga are often outside the awareness and experience of this group of disconnected whānau (Lawson-Te Aho, 2010). These are the people who might benefit most from solutions to Māori homelessness that are grounded in connection to Māori communities, cultural practices, worldviews and values. Whilst homelessness for Māori is complex and diverse, a pattern of disconnection consistent with Durie's classifications arises in stories from people with lived experience. In a storytelling project in Te Whanganui-a-Tara (Wellington), Māori participants highlighted the experience of state care and juvenile detention as catalysts towards homelessness, as well as difficult home environments (Ngā Taonga & Te Pūaroha Compassion Soup Kitchen, 2018). One participant penned a poem about disconnection from cultural roots (Ngā Taonga & Te Pūaroha Compassion Soup Kitchen, 2018, p. 61).

Māori historical narratives of resistance, resilience, and survival in response to these traumatic histories suggest that solutions to Māori homelessness provide opportunity for the tangible and outward expression of Māori cultural values of whanaungatanga, manaakitanga, aroha, and kohā (Groot, Hodgetts, Nikora, & Leggatt-Cook, 2011; Groot, Hodgetts, Nikora, & Rua, 2011).That is, reclaiming Māori cultural practices (decolonisation) such as the development of collective cultural housing. There are many examples of resilience and survival of Māori impacted by the enduring effects of colonisation that move beyond traumatising histories, beyond survival to pro-active reclaiming and stepping into multi-generational solutions that give revitalised meaning to being Māori anchored in reclaimed Māori cultural values, principles, and aspirations and rights. Exemplars in this space can be seen in the work of Durie (Lawson-Te Aho, 2010) who stated that whānau working to support each other is an important contributing factor for building whānau strength, resilience and wellbeing. The transformation of thinking about building onto the capacity of whānau to provide their own solutions to the challenges that confront them is exemplified in a unique New Zealand government policy called Whānau Ora. This is a government sponsored policy that offers a specialised response to Māori homelessness centered on collective whānau-centered intervention design (Te Puni Kōkiri, 2017).

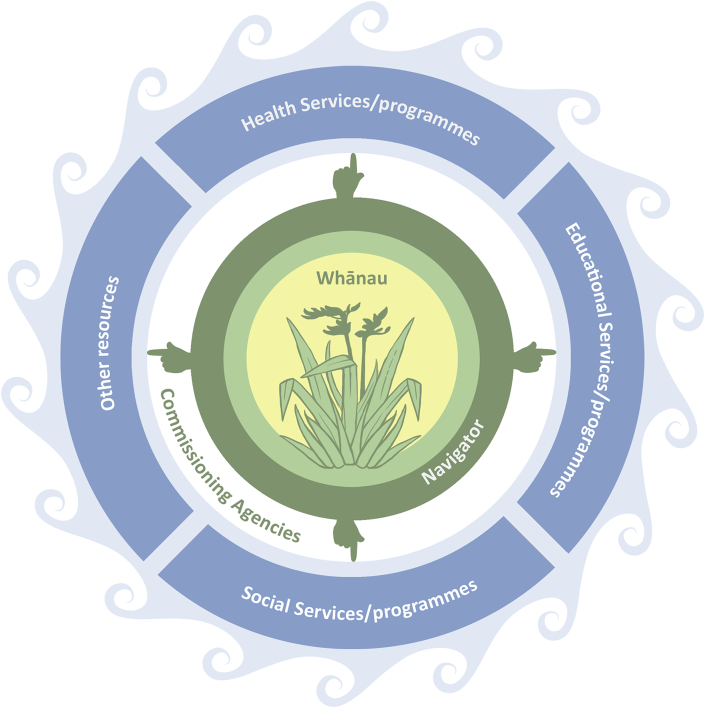

Whānau Ora combines the legislative and principles framework established in the text of the two versions (Māori and English) of Te Tiriti o Waitangi with Whānau Ora, to reorient public health practice into a government sponsored, whānau-centered approach to Māori wellbeing. Whānau Ora translates as the complete wellbeing of Māori families. Safe, affordable, warm, health affirming housing anchored in Māori cultural structures, values and principles is a key policy and practice challenge for those working within the Māori homelessness space. However, there is extensive scope in the alignment between Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles and Whānau Ora to begin to shift responses to Māori homelessness towards a more self-determining set of practices that align with iwi, hapū and whānau development (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Whānau diagram.

1.2. Housing First

A leading effort internationally to end homelessness is Housing First. Housing First is an approach to expedite permanent housing without preconditions and barriers to entry, such as service participation requirements. Support services are offered to maximise housing stability, to prevent returns to homelessness, and improve outcomes and wellbeing, as opposed to addressing pre-determined treatment goals prior to permanent housing entry. Services are informed by harm reduction and self-determination (Pleace, 2011; Sam Tsemberis, 2013). Housing First rests on the premise that housing is a human right, and that the best place from which to address complex issues is from within the stability and security of permanent housing.

Housing First has been successfully implemented in many contexts, including throughout the US, Canada, and the European Union. Positive outcomes, including reduced ill health and accidents, reduced imprisonment, reduced costs of homelessness, and greater integration into communities, have been shown in varying degrees across all contexts (Busch-Geertsema, 2014; DeSilva, Manworren, & Targanoski, 2011; Goering et al., 2011; Kuehn, 2012; Ly & Latimer, 2015; Russolillo, Patterson, McCandless, Moniruzzaman, & Somers, 2014). Despite this success, and a somewhat developed literature on indigeneity and homelessness (Leach, 2010; Memmott, 2015; Memmott, Birdsall-Jones, & Greenop, 2012; Parity Magazine: Responding to Indigenous Homelessness in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, 2016; Parsell, 2018), there has been relatively little attention paid to the experience of Housing First for indigenous people, and for the implications of Housing First in relation to indigenous worldviews, principles, and frameworks.

A report on the implementation of Housing First in Australia for example, where indigenous people have four times the rate of homelessness as the general population (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011), did not make any mention of the implications of the Housing First programme for indigenous people (G. Johnson, Parkinson, & Parsell, 2012). However, it did make two salient points. Firstly, that Housing First-type programmes will need to adapt to the local context and conditions; we take this to infer responding to the particular demographics and needs of the local homeless population as well as the local policy context. Second, that whilst Housing First has been successful at housing people, it has been less successful at effective social integration (G. Johnson et al., 2012, p. 11). Given the centrality of more relational concepts in indigenous definitions of homelessness, social integration may be a meaningful outcome for indigenous people.

One of the more developed examples in the literature is on the experience of indigenous peoples in Canada (including First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples), who are overwhelmingly overrepresented in the Canadian homeless population (The Homeless Hub, 2016). A report on the experience of First Nations people housed through a Housing First programme in Edmonton, Alberta, made the claim that “the Housing First model, due to its client-centred and harm reduction approaches, is evolving towards adoption of a decolonisation process in the way it is delivered” (Bodor, Chewka, Smith-Windsor, Conley, & Pereira, 2011). Whereas more paternalistic approaches to homelessness responses may be seen to continue a pattern of colonisation, the upended (bottom up) values of a Housing First approach – including self-determination, respect, and autonomy - according to the Alberta report, has the potential to contribute to a ‘vibrant future’ for indigenous communities in Alberta.

The challenge for Māori is addressing concerns around collective self-determination rather than the deconstructed focus on individual self-determination. This means in practice, that Housing First might best operate on a clear and committed understanding of the whakapapa or kinship of the homeless indigenous person in the context of their cultural communities and connections. For Housing First to respond to the context of Māori homelessness, a wider understanding of homelessness and home is required, in line with the indigenous definitions of homelessness described earlier. A Māori sense of place is described by Walker, who asserts that mythology, tradition and histories all make vital contributions to the ‘deeply rooted sentiments of Māori attachment to land’ (Walker, 1990, p. 70). In Māori cultural narratives, land is personified as Papatūānuku, earth mother from whom all terrestrial life springs and to which all returns in death. Māori were traditionally organised as small whānau/family units and hapū/sub tribes/collectives of whānau bonded to locations by communal practices such as māra kai/gardening, resource utilisation, defence against invaders, burial sites and the consecration of sacred sites (Waitangi Tribunal, 2004). Māori homelessness is about considerably more than a structure or dwelling, but an opportunity for the lived expression of Māori identities. The main objective of this research was to develop a principles framework to inform indigenous homelessness interventions for Māori incorporating Tino Rangatiratanga (Māori self-determination), Whānau Ora and Housing First.

2. Method

A Kaupapa Māori Research process was applied in this small study of twenty Māori experts speaking about Māori homelessness. The key informants included Māori researchers, Te Tiriti experts, Kaumātua/esteemed elders; researchers, academics, Māori homelessness activists and experts in decolonisation and re-indigenisation. These informants participated on the basis of anonymity to help ensure open discussion. Ethics approval was given by [redacted for peer review]. Two participants had lived experience of homelessness, and half had experience with homelessness in their own whānau. Others had experience working in the homelessness sector. Participants were gathered through a triangulation process from existing contacts who were known to be leaders, and people working in the housing and homelessness kaupapa. In addition, a member of the research team had lived experience of homelessness, and others in the research team had extensive experience either in homelessness kaupapa or Kaupapa Māori research (see Fig. 2).

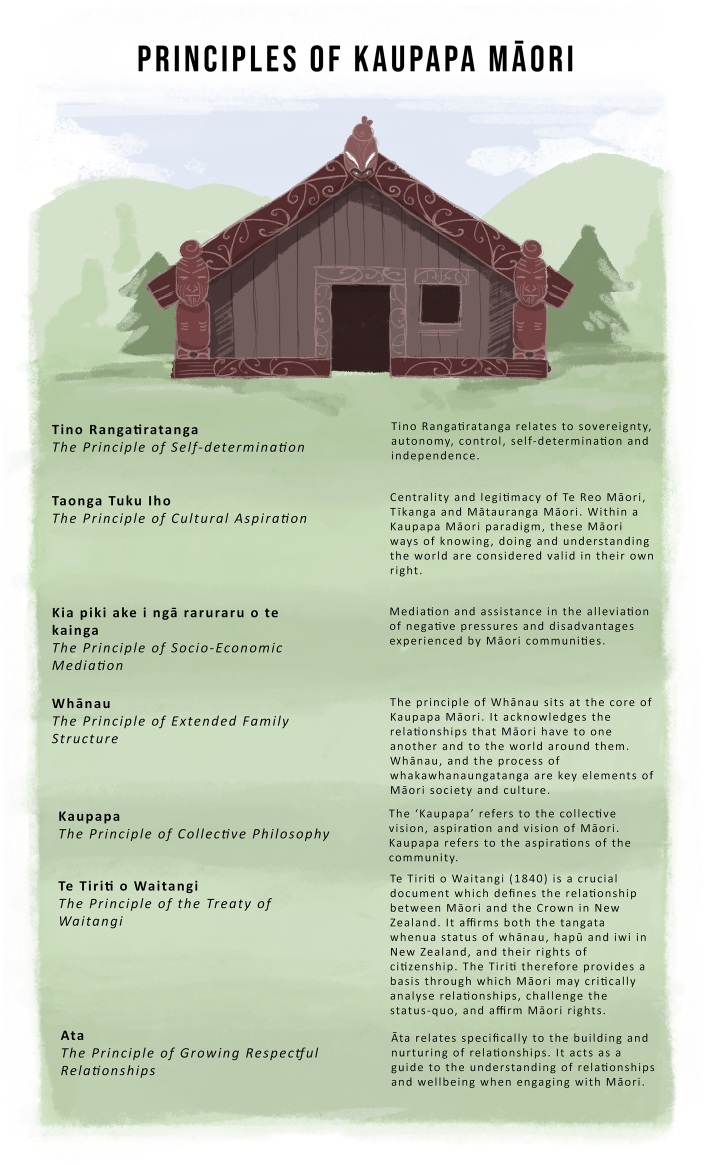

George et al., (2017) clarifies that Kaupapa Māori Research (KMR) grew out of a resistance to the marginalisation of Māori in Aotearoa/New Zealand (Bishop, 1996; George et al., 2017; L. T.; Smith, 1999; Walker, 1990). Moreover, Bishop (1996) argued that research with Māori must have a “methodology of participation” with research being “participant-driven” (Bishop, 1996, p. 224; 226). Pipi et al. (2004) define Kaupapa Māori as an “emancipatory theory” in which a common goal is the self-determining right to have, for example, research theories, methods and methodologies which “enrich, empower and enlighten” all those who are involved in any particular research project (Pipi et al., 2004). Kaupapa Māori is therefore a critical theory which discusses “notions of critique, resistance, struggle, and emancipation” (L. T. Smith, 1999, p. 3). Kaupapa Māori research practices advocate the legitimacy of Māori knowledge, culture and values as given, and has a clear emancipatory agenda. Key values underpinning Kaupapa Māori research include an unequivocal commitment to research that advances Māori development, preserves, protects and grows Mātauranga Māori or Māori knowledge and for whom, and those on the receiving end of the research process are instrumental in having their voices influence and direct the research process. Smith (1990) outlines the key principles underpinning KMR (G. H. Smith, 1990), shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Principles of kaupapa Māori (from Smith, 1990).

2.1. The research questions

Two questions were administered to twenty Māori research participants:

-

1.

What are your views about Māori homelessness? Prompt – how should Maori homelessness be solved?

-

2.

Which principles should underpin Māori housing and homelessness policy, research and action?

Interviews were conducted at a place nominated by the participant, by a Māori student who was involved with the research team, and the lead author. The themes from the interviews were coded and analysed by the student under supervision from the lead author (Clark & Braun, 2014), using the principles of Kaupapa Māori research as a theoretical and analytical framework (intended to advance Māori aspirations for self-determination). As defined by Clark and Braun (2014), this approach reflects a theoretical thematic analysis, which is driven by the ‘theoretical and epistemological commitments’ of the researcher. Following from the principles of Kaupapa Māori methodology, the existing knowledge and relationships of the researcher(s) informs the theoretical thematic analysis, in an iterative way with research participants. Superordinate themes were identified that aligned directly with Kaupapa Māori principles. Sub-ordinate themes were those themes that clarified the superordinate themes. The emergent themes aligned with existing discourse in Aotearoa about Māori agency and housing. These themes were reaffirmed after discussion with the original participants.

2.2. Visual representation of approaches

The representation of public health concepts through visual means is a valuable component of communication and dissemination, and assists in effective translation of policy implications (Bernhardt, 2004; Ombler & Donovan, 2017). Visual methods have previously been used to bridge Māori and non-Māori perspectives in research (Bryant, Allan, & Smith, 2017). A visual representation of the framework developed in this paper, was considered to be an effective means of distilling the complex interactions of the three sets of principles discussed. A Māori graphic artist was commissioned to design the diagram.

3. Results

The results of the interviews are reported as key themes using verbatim comments from the informants to highlight their key ideas. The themes from the research were triangulated with key aspects of Māori and indigenous homelessness, and Māori aspirations to lead Māori development responses situated in iwi/tribal development opportunities under Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

3.1. Theme: Māori worldview and Māori values

Whakapapa is the foundation of our worldview. It conveys and confers principles, ethics, determines Tikanga, roles within the iwi, hapu, whānau, moemoeā, kaupapa … and much more. (Kaumātua)

Māori values evidenced in our work are core Māori values aroha, manaakitanga, awhi – speak up for those without a voice; help because you can; extend love and support to those who may be deemed unlovable by society and deviant/undeserving by government decree (through policies). (Māori activist)

Whakapapa or kinship is identified as the foundation of a Māori worldview. Each iwi has its own whakapapa, stories and narratives of ancestors, their feats and legacies and capacity to reconnect current day descendants of ancestors with their whānau, hapū and iwi. Whakapapa creates a duty of care for those who are joined together by blood and common ancestry.3 This is not a treatise on specific Māori values. It is recognition that Māori worldviews and values are foundational when developing solutions to Māori homelessness.

3.2. Theme: Te Tiriti o Waitangi

Māori homelessness is a Treaty issue (Māori activist)

Failure to fully honour Te Tiriti has produced homeless whānau in our own homelands, our own whenua (Māori activist)

Te Tiriti o Waitangi is the foundational document for New Zealand, and is critical to addressing all aspects of the relationship between the ‘colonial settler government’ and Māori. The Crown is obligated to protect Māori Tiriti rights. The right to self-determination or Tino Rangatiratanga is foremost amongst these.

The Māori version of Te Tiriti guarantees our Rangatiratanga. We never gave up our right to exercise Rangatiratanga. Why would we? Not only was that culturally unachievable, it makes no sense that would actually happen. That is a lie, a fabrication (Māori Treaty expert)

Principles shift. The language of the Māori version of the Treaty is clear and rights based (Māori Treaty lawyer)

The precedence in international law of treaties written in the indigenous language having legal precedence (contra proferentem4 rule) has not been upheld with Te Tiriti o Waitangi. However, according to these respondents, that does not negate Tino Rangatiraranga, and the Waitangi Tribunal's 2014 report that Māori did not cede sovereignty supports this view (Waitangi Tribunal, 2014). Te Tiriti has a role in addressing the enduring effects of colonisation and in giving effect to Tino Rangatiratanga, making clear that there is a role for Iwi to play in addressing Māori homelessness.

It is important to define the spheres of Tiriti influence. The government interprets and enacts Te Tiriti o Waitangi in hauora in the form of three (tiriti) principles of partnership, participation and protection. These principles directly link to article three which called upon the colonial government to treat Māori as ‘having the same rights and privileges as British subjects”. A modern interpretation is reducing inequalities and inequities in Māori homelessness relative to the whole population. Te Tiriti therefore also provides a legitimate mechanism to challenge the government to take action to end Māori homelessness.

3.3. Theme: colonisation – as both causal and explanatory of Māori Homelessness

Māori homelessness is an outcome of colonisation (Māori activist)

…. .the duplicity of the wording of the Māori and English versions of the Treaty has cast Māori into homelessness by rendering us/them homeless in our own lands from the mass alienation of our lands and attack on our sovereignty (Māori Treaty lawyer)

The explanations for Māori homelessness are firmly anchored in colonisation and the rapid alienation of Māori land, destruction of a Māori economic base, demise of Māori worldviews and oppression of Māori during the colonial period of New Zealand history and beyond. The effects of colonisation are asserted to pass from generation to generation through the mechanics of colonisation and historical trauma, defined as “… cumulative emotional and psychological wounding, over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma experiences” (Brave Heart, 2003). The generational effects of dispossession and cultural decimation are explanatory of Māori homelessness creating an imperative for change beginning with decolonisation. This finding aligns with the approach of Housing First in Aboriginal communities in Edmonton, Canada, in which all staff are trained in culturally-appropriate service, and Native agencies – the Bent Arrow Trust and the Native Counselling Services - are partners in delivering HF, and lead the HF programme for indigenous people (Alberta Native News, 2017; Bodor et al., 2011). Decolonisation in this context is viewed as both individual and collective, leading to ‘increased self-determination, social, economic, cultural and political independence and identity development’ ((Verniest, n.d.) cited in (Bodor et al., 2011)).

3.4. Theme: Tino Rangatiratanga/Self Determination

The Treaty is an agreement that can be adapted to meet new circumstances - the principle of development (Māori Treaty lawyer)

Notwithstanding the two different versions of the Te Tiriti o Waitangi that differ on the extent to which government recognises a right to a home, self-determination is widely considered to be a critical principle underpinning homelessness solutions (Sam Tsemberis, 2013; S. Tsemberis, Gulcur, & Nakae, 2004). In these interviews, the right to self-determination was unanimously associated with all levels of action on Māori homelessness. For example, a duty of iwi to act on their position as “sovereign iwi nations” was identified by several of the respondents. Tino Rangatiratanga is used more often in public policy discourse around iwi taking charge of the responses to the needs of their populations. The duties of the government to enact as a fiduciary duty/caretaker duty in the form of good governance towards New Zealanders, including enacting policies and legislation that further promote equity in housing, health, education cannot be transferred to iwi without their consent. Even then,

“the duties enshrined in articles 1 and 3 of the English language version of the Treaty, the basis for the establishment of the government in Aotearoa/New Zealand, must be upheld” (Māori Treaty lawyer).

The shape and form of Tino Rangatiratanga as found in HF is to empower clients (individuals and/or their families) to make decisions around their housing requirements which is framed as self-determination and consumer choice. The shape and form of Tino Rangatiratanga from an Iwi view is to support the aspirations of those who whakapapa/are direct descendants of the iwi and hapū by birth right and blood. In this case, the iwi leadership is culturally bound to progress the aspirations of the whakapapa/blood descendants of the iwi and hapū (Graham, 2005). This is a very different responsibility and duty of care from Māori consumer choice and self-determination.

3.5. Theme: Te Tiriti underpins rights based discourse

A home is a right guaranteed in Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Government as Treaty partner is legally and morally obliged to act to end Māori homelessness (Māori researcher/academic).

The case for ending Māori homelessness is anchored in Te Tiriti. A rights argument underpins ending homelessness as a human right, an indigenous right in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and a Māori right in Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Any intervention must therefore recognise housing as a right.

3.6. Theme: decolonisation and Re-indigenisation

The time to decolonise Māori homelessness is long overdue but decolonisation is only part of the process. Re-indigenisation is the next part of the process (Māori activist)

The agenda for decolonisation of homelessness discourse has been promoted in homelessness studies with indigenous populations (Christensen, 2013). Decolonisation refers to unpacking the effects of colonisation and its instrumentality in creating homelessness, in this case Māori homelessness in a land that was once fully controlled by Māori.

The agenda for decolonisation must also include the agenda for re-indigenisation, reclaiming Māori ways of (in this case) housing our whānau who are homeless (Māori researcher/academic)

Re-indigenisation refers to reclaiming and reasserting Māori ways, values, processes, tikanga and kawa as the primary pathways by which to respond to homelessness. For example, the re-development of papakāinga (collective housing on tribal land); Māori architectural forms/vernacular architecture (marae-style housing) and other forms of housing that reflect Māori values, practices and worldviews.

3.7. Whare Ōranga framework

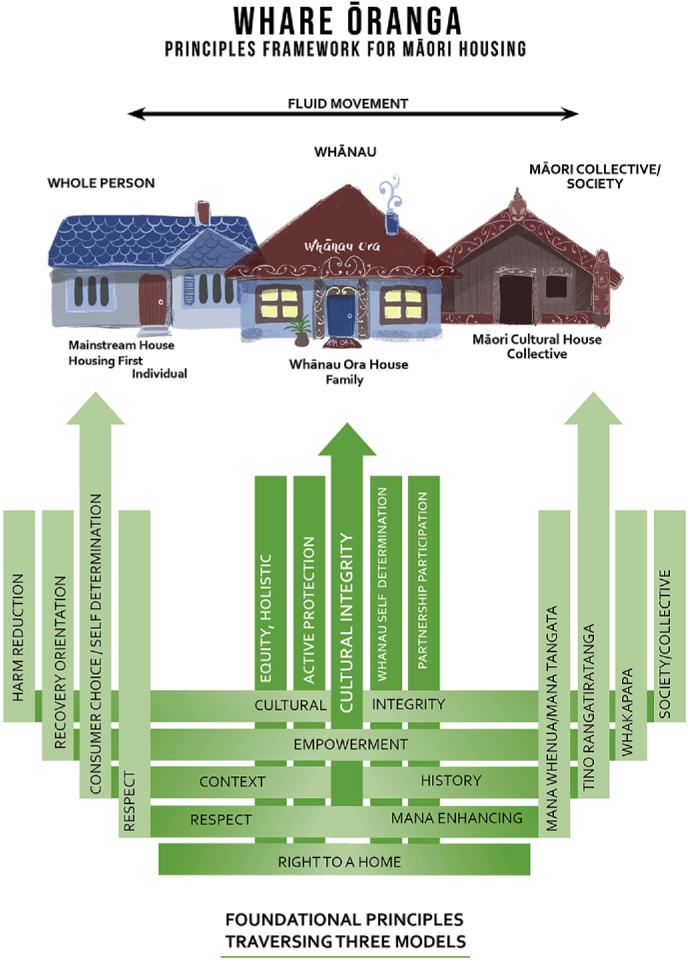

The Principles Framework for Māori Housing shows the principles underpinning Housing First. HF focuses on the individual and their family; whereas, Whānau Ora focuses on the cultural collective of whānau and the principles of the Te Tiriti o Waitangi. In a self-determining model i.e. the Māori cultural house in the model below, Tino Rangatiratanga is anchored in Te Tiriti o Waitangi, that addresses homelessness at the Māori collective, societal level and which guarantees Māori control over all aspects of Māori well-being and development. Each part of the model enables different action to be taken to end Māori homelessness. The model is fluid, empowering Māori individuals and their whānau to move from Housing First to Whānau Ora to Tino Rangatiratanga housing and back again (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Whare Ōranga: A principled model for action on Māori homelessness.

This framework is collated from the views collected above. This is a visual representation of a holistic approach to addressing Māori homelessness, and the foundational principles that traverse the three models.

4. Discussion

Homelessness is particularly destructive and common for Māori, and there is a clear obligation on the NZ government and Iwi to address this. Solutions need to: encourage Self Determination; work with the existing framework of Whānau Ora; and draw on international best practise such as Housing First.

Article Two of Te Tiriti legitimates Māori control over Māori possessions, and Māori self-determination.

In 1991 the Waitangi Tribunal said, ‘The cession by Māori of sovereignty to the Crown was in exchange for the protection by the Crown of Māori rangatiratanga (Waitangi Tribunal, 1991).

In our context, this article creates a duty to support iwi self-determination and iwi-led development including papakāinga housing. Some iwi (for example, Ngāi Tāhu/Tainui) who have received payment to settle historical grievances and the claims of justice are now actively involved in housing their people. For example, papakāinga/communal housing development on tribal lands is an example of Māori led solutions although somewhat constrained within the ambit of government policy. Iwi/tribal-led papakāinga/communal housing development enabled by financial settlements for breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi have and continue to enable iwi to fund papakāinga housing on Māori land, thereby drawing Māori with tribal connections, home to the tribal fold. There are a number of opportunities to respond to Māori homelessness in ways that strengthen and rebuild Māori collective cultural practices with papakāinga (communal housing) being one pre-eminent model of practice that situates and nestles Māori homelessness within a greater tribal context. One such example is papakāinga developments that Ngāi Tahu has initiated. Those developments, such as homes on land at Tuahiwi marae near Kaiapoi (McLachlan, 2019), are on tribal land and therefore, Ngāi Tāhu whānau (those who can prove their ancestry) have first right to be housed. Ngāi Tāhu's core value of manaakitanga, caring for everyone within the tribal area also means that non-Ngāi Tāhu can access the benefits of Ngāi Tāhu led development in a controlled way. The existence of papakāinga housing does not remove the state's fiduciary duty towards those in need.

In direct response to the experience of Māori homelessness, some initiatives reflect the principles developed in the model, though these may require greater support and integration. A Kāinga Strategic Action Plan has been developed by the Independent Māori Statutory Board in Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland), which emphasises the principles of Te Tiriti, whānau-focused approaches, and ending homelessness as a critical outcome (Independent Māori Statutory Board, 2019). As a direct response to a homeless crisis point, Te Puea Marae, an urban marae in Tāmaki Makaurau, has enacted the principle of manaakitanga by opening as a shelter during winter months, and by assisting people into housing (Neilson, 2018). Their tikanga approach views that people who are assisted become part of the wider Te Puea whānau, and are integrated into the Te Puea community. Also in Tāmaki Makaurau, Ngāti Whātua at Ōrākei Marae create a sense of belonging and connection for local homeless people by engaging them in māra kai (communal food gardens) (King, 2014). This has been viewed as helping to establish a sense of identity and connection to Māori cultural values and practices (King, 2014).

Derived from the principles of Te Tiriti, New Zealand has a framework for Māori wellbeing, called Whānau Ora, grounded in the central role of whānau/family in Māori well-being (Kara et al., 2011; Kidd, Gibbons, Lawrenson, & Johnstone, 2010; Te Puni Kōkiri, 2017). Whānau Ora, literally meaning the complete wellbeing of Māori families, is a government model that deconstructs artificial barriers between housing, health, and education, integrating them into one model of care that is driven by the whānau based on their priorities. It is an inside out model rather than the typical government-funded outside in model of intervention. Whānau Ora is continually evolving with large scale Whānau Ora commissioning agencies now managing programme funding for the government. The role of government agencies is diminished in this model and the commissioning agencies are comprised of tribal/iwi representatives to enhance greater alignment between Whānau Ora as a government funded programme and iwi development. The Māori Housing Network, housed within the Ministry of Māori Development (Te Puni Kōkiri) supports whānau, hapū and individuals, whānau and rōpū with practical support and financial assistance for a range of housing activities. It supports whānau with information, advice and practical support to improve and develop whānau housing and works alongside whānau, hapū and iwi to help them with housing goals, project planning, developing funding proposals, and providing agreed funding as projects are implemented. Whānau Ora works at the collective level of whānau/extended family networks.

Based on Article One of Te Tiriti, in the 1990's a fiduciary duty was described by the courts requiring the government to protect Māori interests. The wellbeing of homeless Māori is one such Māori interest requiring protection. The protection of Māori interests to be housed and not be homeless is visible in Housing First, Aotearoa although not explicitly stated as a Tiriti based commitment. Housing First offers a universalist approach to housing the homeless based on need rather than, for example, specific Māori cultural imperatives. While the HF work with a small Aboriginal population in Edmonton, Canada is evolving, evaluation findings from 2010 recommended that HF undergo a programme of decolonisation and that an Aboriginal worldview underpin their work with this population (Bodor et al., 2011). Whether that has implications for HF Aotearoa's work with Māori is unclear.

Article Three of the English version of Te Tiriti afforded “Māori the “same rights and privileges as British subjects”("Treaty of Waitangi," 1840). This is often called the ‘equity principle’ that legitimates Māori access to government funded services alongside any other New Zealander. While barriers to access and differential access to care have been found to impede and deny equitable outcomes for Māori, Māori have a right to a home. We will know our framework has succeeded if Māori are no more likely to be homeless than Pākeha, preferably by ending homelessness in both groups.

5. Conclusion

The Whare Ōranga model recognises the right to a home with the entitlement sourced in different places. For example, Housing First operates on the Human Rights principle of a ‘right to a home’; Whānau Ora operates specifically on the basis of the core Māori value of whanaungatanga, a more collective approach to Māori homelessness that extends beyond the individual centered approach of Housing First.

There is a close and growing alignment between Whānau Ora and iwi self-determination in strategies and actions to support Māori into a home. Tribal self-determination models work to capitalise on tribally owned land to house whole communities of Māori connected by whakapapa/kinship. Two approaches to Housing First are commonly used: scatter site, or congregate housing. The scatter-site approach has been credited with better outcomes, argued as being due to integration with a more diverse community than congregate sites would encourage, and by avoiding concentrations of disadvantage. An indigenous connection-based approach may offer a solution to the initial loss of peer connections seen in scatter-site models of Housing First in Europe (Busch-Geertsema, 2014).

There is alignment between the practice principles of Housing First, Whānau Ora and Tino Rangatiratanga (Tribal and Cultural Self Determination), with each making a potentially vital contribution to ending Māori homelessness. However, the potential of a practice alignment between the three approaches is yet to be fully realised. This framework has been discussed with interested partners, including the Auckland Housing First collective and their Māori governance board, the Independent Māori Statutory Board, the Housing First community of practice, and the Ministry of Social Development. There was strong support for a collective vision between programs from the Māori organizations, but most noted that it assumed a capacity and funding for Whānau Ora and papakāinga housing that does not currently exist. Greater effort is needed in New Zealand to manage and fund programs holistically especially across government ministries and funding streams. It should be achievable to more closely align the efforts of Housing First, Whānau Ora and Iwi Self Determination and a test case of such an alignment might be sought particularly with tangata and whānau Māori who are estranged from their cultural identities and have no pathway back to reconnecting with Māori cultural whānau, hapū, and iwi frameworks. Such alignments will depend on the local context, however resourcing and flexibility of funding by central government is a precursor to any large pilots.

The Principles model in this study is fluid, allowing for movement between three distinctive types of action on Māori homelessness anchored in three different relationships underpinned by the Te Tiriti o Waitangi and exemplified in Housing First, Whānau Ora and iwi self-determination. Ideally, being able to join the dots between Housing First, Whānau Ora and Tribal Housing initiatives, might just fulfil the vision of ending Māori homelessness permanently. That is certainly the potential of aligning the principles of practice of the three approaches for the development of a cohesive, integrated and workable implementation trial. Moreover, this exploration of the ways in which the principles of Housing First can connect to indigenous principles in New Zealand adds to the international picture of Housing First's relationship to indigenous communities in colonised countries.

Ethics

Ethical approval was given by the University of Otago Human Research Ethics Committee ref D18/274.

Footnotes

This research was made possible with funding from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (New Zealand) as part of the Ending Homelessness in New Zealand: Housing First research programme.

Please see Glossary for translations of words in Te Reo Māori.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi and its associated offices, the Waitangi Tribunal, and the Office of Treaty Settlements, as well as the Māori Land Court.

There is also a process of whāngai or cultural adoption that enacts the duties of whakapapa. Whāngai was not raised as a value in this study but it is an important consideration in the enactment of duties of care or manaakitanga.

The contra proferentem rule states, broadly, that where there is doubt about the meaning of the contract, the words will be construed against the person who put them forward.

Glossary:

Most of these definitions were obtained via the Māori dictionary (Moorfield, 2017).

- Aotearoa

New Zealand.

- Aroha

love, compassion, empathy

- Awhi

to embrace, cherish

- Hapū

kinship group, sub-tribe, clan. The primary political unit in traditional Māori society. A number of related hapū sharing adjacent territories usually form a looser tribal federation (iwi)

- Hauora

Health, wellbeing

- Iwi

tribe, extended kinship group, or nation, usually formed of a series of sub-tribes (Hapū)

- Kaumātua

esteemed elders

- Kaupapa

topic, programme, policy, matter for discussion, initiative.

- Kaupapa Māori

A Māori approach, topic, or customary practice.

- Kawa

Maori protocol and etiquette

- Kohā

gift, offering, contribution

- Māori

a collective term for the indigenous people of Aotearoa/New Zealand.

- Mana

prestige, authority, status

- Manaakitanga

hospitality, kindness, generosity

- Māra kai

garden

- Marae

the open area in front of the wharenui (large meeting house) where formal greeting and discussions take place. Often also used to refer to the complex of buildings around the marae

- Mātauranga Māori

Māori knowledge and wisdom

- Moemoeā

dream

- Ngāi Tāhu

the principal Māori Iwi of the southern region of New Zealand.

- Pākehā

A collective term for New Zealanders of European descent

- Papakāinga

housing development for Māori on their ancestral land.

- Papatūānuku

Earth, Earth mother and wife of Rangi-nui (the sky) – all living things originate from them

- Pōhara

poor, impoverished, poverty-stricken

- Rōpū

group, party of people

- Rūnanga

council or iwi authority – assemblies called to discuss issues of concern to iwi or the community

- Tangata

Human, individual

- Te Tiriti o Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840, between the British Crown and most (not all) Māori leaders of Iwi

- Tikanga

custom, correct procedure

- Tino Rangatiratanga

Self-determination, sovereignty

- Tūkino

Oppression

- Tū-mokemoke

Stand alone, solitary

- Wetewete

Undo or unravel

- Whāngai

customary practice of fostering or adopting a child, normally related by blood

- Whakapapa

genealogy

- Whānau

Family and extended family

- Whānau Ora

Family health – a New Zealand governmental programme to empower and increase the wellbeing of communities and extended families, driven by Māori cultural values

- Whanaungatanga

relationship, kinship, sense of family connection

- Whare Ōranga

House (Whare) Wellbeing (Ōranga)

- Whenua

land, nation, placenta

References

- Alberta Native News . 2017. Two new housing first teams to help end homelessness in Edmonton.https://www.albertanativenews.com/two-new-housing-first-teams-to-help-end-homelessness-in-edmonton/ [Google Scholar]

- Amore K. 2016. Severe housing deprivation in Aotearoa/New Zealand 2001-2013.http://www.healthyhousing.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Severe-housing-deprivation-in-Aotearoa-2001-2013-1.pdf Retrieved from Wellington. [Google Scholar]

- Amore K., Viggers H., Baker M., Howden-Chapman P. 2013. Severe housing deprivation: The problem and its measurement.www.statisphere.govt.nz Retrieved from Wellington. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . 2011. A profile of homelessness for aboriginal and torres strait islander people.https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/9d3002f1-b68e-4c63-ac67-0e783698e381/12344.pdf.aspx?inline=true Retrieved from Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt J.M. Communication at the core of effective public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(12):2051–2053. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierre S. Doctor of Philosophy), University of Otago; Dunedin: 2009. Constructing housing quality, health, and private rental housing: A critical analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham B., Moniruzzaman A., Patterson M., Distasio J., Sareen J., O'Neill J. Indigenous and non-indigenous people experiencing homelessness and mental illness in two Canadian cities: A retrospective analysis and implications for culturally informed action. BMJ Open. 2019;9(e02478) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024748. 10/1136/bmjopen-2018-024748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop R. Dunmore Press Ltd; Palmerston North: 1996. Whakawhānaungatanga: Collaborative research stories. [Google Scholar]

- Bodor D.R., Chewka D., Smith-Windsor M., Conley S., Pereira N. 2011. Perpectives on the housing first program with indigenous participants.http://homewardtrust.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Perspectives-on-the-Housing-First-Program-with-Indigenous-Participants.pdf Retrieved from Canada: Blue Quills First Nation College. [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart M.Y.H. The historical trauma response among natives and its relationship with substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):7–13. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant M., Allan P., Smith H. Climate change adaptations for coastal farms: Bridging science and Mātauranga Māori with art and design. The Plant Journal. 2017;2(2):497–518. [Google Scholar]

- Busch-Geertsema V. Housing First Europe - results of a European social experimentation project. European Journal of Homelessness. 2014;8(1) [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J. Our home, our way of life': Spiritual homelessness and the sociocultural dimensions of indigenous homelessness in the northwest territories (NWT), Canada. Social & Cultural Geography. 2013;14(7):804–828. [Google Scholar]

- Clark V., Braun V. Thematic analysis. In: Teo T., editor. Encyclopedia of critical psychology. Springer; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- DeSilva M.B., Manworren J., Targanoski P. Impact of a housing first program on health utilization outcomes among chronically homeless persons. Journal of Primary & Community Health. 2011;2(1):16–20. doi: 10.1177/2150131910385248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durie M.H. Whanau, whanaungatanga, and healthy Māori development. In: Te Whaiti P., McCarthy M., Durie A., editors. Mai i rangitea. Auckland University Press; Auckland: 1997. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- George L., Dowsett G., Lawson Te-Aho K., Milne M., Pirihi W., Flower L. 2017. Final report for project He Ara Taiora: Suicide prevention for Ngātiwai youth through the arts (LGB-2016-28888) (Retrieved from Whāngarei) [Google Scholar]

- Goering P., Streiner D., Adair C., Aubry T., Barker J., Distasio J. The at home/chez soi trial protocol: A pragmatic, multi-site, randomised controlled trial of a housing first intervention for homeless individuals with mental illness in five Canadian cities. BMJ. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000323. http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/1/2/e000323.full.pdf Open, November 14(1(2)) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J. He āpiti hono, he tātai hono: That which is joined remains an unbroken line: Using whakapapa (genealogy) as the basis for an indigenous research framework. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education. 2005;34:86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Groot S., Hodgetts D., Nikora L., Rua M. Māori and homelessness. In: McIntosh T., Muholland M., editors. Māori and social issues. Huia Publishers; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Groot S., Hodgetts D., Nikora L.W., Leggatt-Cook C. A Māori homeless woman. Ethnography. 2011;12(3):375–397. [Google Scholar]

- Harris R., Tobias M., Jeffreys M., Waldegrave K., Karlsen S., Nazroo J. Effects of self-reported racial discrimination and deprivation on Māori health and inequalities in New Zealand: Cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2006;367(9527):1958–1959. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68890-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgetts D., Radley A., Chamberlain K., Hodgetts A. Health inequalities and homelessness: Considering material, spatial and relational dimensions. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12(5):709–725. doi: 10.1177/1359105307080593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Independent Māori Statutory Board . 2019. Kāinga: Strategic action plan.https://www.imsb.maori.nz/publications/kainga-strategic-action-plan/ Retrieved from Auckland. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A., Howden-Chapman P., Eaqub S. 2018. A stocktake of New Zealand's housing.https://www.beehive.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2018-02/A%20Stocktake%20Of%20New%20Zealand%27s%20Housing.pdf Retrieved from Wellington. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G., Parkinson S., Parsell C. 2012. Policy shift or program drift? Implementing housing first in Australia.https://www.ahuri.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/2064/AHURI_Final_Report_No184_Policy_shift_or_program_drift_Implementing_Housing_First_in_Australia.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kara E., Gibbons V., Kidd J., Blundell R., Turner K., Johnstone W. Developing a kaupapa Māori framework for whānau ora. Alternative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples. 2011;7(2):100–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd J., Gibbons V., Lawrenson R., Johnstone W. A whanau ora approach to health care for Maori. Journal of Primary Health Care. 2010;2(2):163–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King P. University of Waikato; 2014. Homeless Māori men: Re-connection, Re-joining, and Re-membering ways of being. (Master of applied psychology (community psychology))https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10289/8783/thesis.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn B.M. Supportive housing cuts costs of caring for the chronically homeless. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308(1):17–19. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws D. 2016. Māori, aboriginal and torres strait islander homelessness. Parity. September. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson-Te Aho K. 2010. Definitions of whānau: A review of selected literature.http://www.superu.govt.nz/sites/default/files/definitions-of-whanau.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Leach A. The roots of aboriginal homelessness in Canada. Parity. 2010;23(9):12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ly A., Latimer E. Housing first impact on costs and associated cost offsets: A review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;60(11):475–487. doi: 10.1177/070674371506001103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan L.-M. New $3.7m housing development signals new era for Christchurch marae. RNZ. 2019, 17 April https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/387264/new-3-point-7m-housing-development-signals-new-era-for-christchurch-marae [Google Scholar]

- Memmott P. Differing relations to tradition amongst Australian indigenous homeless people. Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review. 2015;XXVI(2):59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Memmott P., Birdsall-Jones C., Greenop K. 2012. Why are special services needed to address Indigenous homelessness? Retrieved from Australia:) [Google Scholar]

- Moorfield J.C. 2017. Māori dictionary.http://maoridictionary.co.nz/ [Google Scholar]

- Neilson M. NZ Herald; 2018, 19 September. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12127899 (Te Puea Marae model of manaakitanga 'key' to tackling homelessness crisis). [Google Scholar]

- Ngā Taonga, Te Pūaroha Compassion Soup Kitchen . Te Pūaroha Compassion Soup Kitchen and Massey University School of English and Media Studies; Wellington: 2018. Te hā tangata: A human library on homelessness. [Google Scholar]

- Ombler J., Donovan S. 2017. What does art have to do with public health, and how can they work together?https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/pubhealthexpert/2017/04/10/what-does-art-have-to-do-with-public-health-and-how-can-they-work-together/ [Google Scholar]

- Orange C. Bridget Williams Books; 2015. The Treaty of Waitangi. [Google Scholar]

- Parity Magazine . 2016. Responding to indigenous homelessness in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand.http://chp.org.au/parity/back-issues-and-orders/parity-2016/september-2016-responding-to-indigenous-homelessness-in-australia-and-aotearoa-new-zealand/ [Google Scholar]

- Parsell C. Routledge; Oxon and New York: 2018. The homeless person in contemporary society. [Google Scholar]

- Pipi K., Cram F., Hawke R., Hawke S., Huriwai T., Mataki T., Tuuta C. A research ethic for studying Māori and iwi provider success. Social policy Journal of New Zealand Te Puna Whakaaro. 2004;23 https://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/journals-and-magazines/social-policy-journal/spj23/23-a-research-ethic-for-studying-mori-and-iwi-provider-success-p141-153.html [Google Scholar]

- Pleace N. The ambiguities, limits and risks of Housing First from a European perspective. European Journal of Homelessness. 2011;5(2) [Google Scholar]

- Poata-Smith E.T.A. Inequality and Māori. In: Rashbrooke M., editor. Inequality: A New Zealand crisis. Bridget Williams Books; Wellington: 2013. pp. 148–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ruru J. Papakāinga and whanau housing on Māori freehold land. In: Toomey E., Finn J., France-Hudson B., Ruru J., editors. Revised legal frameworks for ownership and use of multi-dwelling units. Research Report ER23; 2017. pp. 121–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ruru J. 2017. When the home is on Māori Land: Beware the legal issues.http://sustainablecities.org.nz/2017/10/seminar-when-the-home-is-on-maori-land-beware-the-legal-issues/ [Google Scholar]

- Russolillo A., Patterson M., McCandless L., Moniruzzaman A., Somers J. Emergency department utilisation among formerly homeless adults with mental disorders after one year of housing first interventions: A randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Housing Policy. 2014;14(1):79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Smith G.H. Taha Māori: Pakeha capture. In: Codd J., Harker R., Nash R., editors. Political issues in New Zealand education. Dunmore Press Ltd; Palmerston North: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Smith L.T. University of Otago Press; Dunedin: 1999. Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics New Zealand . 2009. New Zealand definition of homelessness. (Retrieved from Wellington) [Google Scholar]

- Te Puni Kōkiri . 2017. Whānau Ora.https://www.tpk.govt.nz/en/whakamahia/whanau-ora/ [Google Scholar]

- The Homeless Hub . 2016. Indigenous peoples.http://homelesshub.ca/about-homelessness/population-specific/indigenous-peoples [Google Scholar]

- Thistle J. 2012. Definition of indigenous homelessness in Canada.https://www.homelesshub.ca/IndigenousHomelessness [Google Scholar]

- Treaty of Waitangi, (1840).

- Tsemberis S. Housing first: Implementation, dissemination, and program fidelity. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2013;16(4):235–239. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2013.847745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsemberis S., Gulcur L., Nakae M. Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(4):651–656. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verniest, L. (n.d.). Allying with the medicine wheel: Social work practice with aboriginal peoples. (Unpublished manuscript. Kanata, Ontario, Canada).

- Waitangi Tribunal . 1991. Ngāi Tahu land report.https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_68476209/Wai27.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Waitangi Tribunal . 2004. The mohaka ki ahuriri report.https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_68598011/Wai201.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Waitangi Tribunal . 2014. Te paparahi o te raki inquiry.http://waitangitribunal.govt.nz/inquiries/district-inquiries/te-paparahi-o-te-raki-northland [Google Scholar]

- Walker R. Penguin; 1990. Ka whawhai tonu matou: Struggle without end. [Google Scholar]

- Walters K. Paper presented at the indigenous indicators of well-being: Perspectives, practices, solutions, Wellington. 2006, 14-17 June. Indigenous perspectives in survey research: Conceptualising and measuring historical trauma, microaggressions, and colonial trauma response. [Google Scholar]