To the Editor:Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is highly prevalent in women. The main risk factors for IDA include a low intake of iron, poor absorption, and high iron requirements such as those observed during pregnancy or with menorrhagia.1

Treatment includes controlling the bleeding and replenishing lost iron. Oral iron remains the front‐line standard primarily because of its convenience and low cost. However, international guidelines recommend intravenous (IV) iron as the preferred route when there is intolerance of oral iron, limited absorption, or when there is a high iron need.2, 3, 4

Iron isomaltoside (also known as ferric derisomaltose) is one of the newer IV iron formulations able to supply a complete replacement dose in a short, single visit in most patients.

Herein, we present data from a subpopulation of gynecology patients with IDA from a previously reported trial.5 The objective was to compare the efficacy and safety of iron isomaltoside to iron sucrose in gynecology patients (corresponding to 48.5% of those in the larger trial) with IDA and who were intolerant of, or unresponsive to oral iron therapy or who would benefit from rapid iron repletion.

Patients were randomized 2:1 to iron isomaltoside (Monofer®, Pharmacosmos A/S, Holbaek, Denmark) or iron sucrose (Venofer®, Vifor Pharma, Glattbrugg, Switzerland).5

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients with a hemoglobin (Hb) increase of ≥2 g/dL from baseline (ie, dosing) at any time from week 1 to 5. Secondary efficacy endpoints were time to Hb increase ≥2 g/dL, and change in Hb, s‐ferritin, transferrin saturation (TSAT), and total quality of life (QoL) score (Short Form 36 [SF‐36] questionnaire). Safety endpoints included the number of patients who experienced any adverse drug reaction (ADR). The primary endpoint was tested for non‐inferiority. If the 95% confidence interval (CI) was above 0, this was evidence of superiority in terms of statistical significance at the 5% level. Remaining endpoints were only tested for superiority.

Two hundred forty‐eight patients were randomized to either the iron isomaltoside (164) or iron sucrose group (84). Baseline characteristics were comparable between the treatment groups. The mean cumulative dose of iron isomaltoside was 1687 (SD: 381) mg and of iron sucrose 1154 (SD: 368) mg. The difference in cumulative doses is reflective of the ability to administer a larger dose of iron isomaltoside in a single setting resulting in fewer administrations and a shorter treatment period to reach the desired iron dose.

The primary analysis was conducted on both the full analysis set (FAS) (N = 237) and the per protocol (PP) analysis set (N = 223).

There were more responders in the iron isomaltoside group compared to the iron sucrose group. A risk difference of 13.9%‐points in the FAS and 14.3%‐points in the PP set as well as non‐inferiority of iron isomaltoside to iron sucrose was observed.

A predetermined test for superiority was performed, confirming superiority of iron isomaltoside over iron sucrose (FAS: P = .033; PP: P = .031).

In the FAS, the largest increase in Hb from baseline to any time from week 1 to week 5 (mean [SD]) was 2.83 (1.33) g/dL in the iron isomaltoside group and 2.34 (1.22) g/dL in the iron sucrose group. Increases in Hb in the PP analysis set were consistent with superiority of iron isomaltoside over iron sucrose (2.88 [1.30] vs. 2.39 [1.20] g/dL). For both FAS and PP, the difference between iron isomaltoside and iron sucrose was statistically significant (P < .001).

Analysis of time to Hb increase ≥2 g/dL showed a statistically significantly shorter time to Hb increase ≥2 g/dL in the iron isomaltoside group compared with the iron sucrose group with a hazard ratio (HR) (95% CI) of 1.71 (0.19; 0.89) (P = .0026).

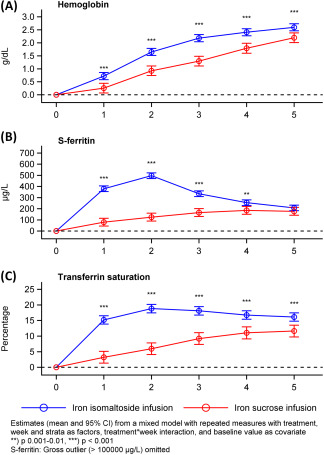

The change from baseline in Hb and TSAT was statistically significantly higher in the iron isomaltoside compared to the iron sucrose group at each time point (P ≤ .0005 and P ≤ .0001, respectively) (Figure 1), and s‐ferritin was statistically significantly higher with iron isomaltoside at weeks 1 to 4 (P ≤ .002) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Change in hemoglobin, s‐ferritin, and transferrin saturation over time by treatment group, full analysis set. CI: confidence interval

In both treatment groups, the SF‐36 scores in the eight health domains improved from baseline to weeks 2 and 5. There were no differences between the groups.

The ADR profiles in the treatment groups were similar to the ones observed in the main trial.5

One (0.6%) in the iron isomaltoside group experienced serious ADRs (serious adverse reactions [SARs]; dyspnea and pruritic rash) for which the patient was admitted to the hospital. On the day after receiving iron isomaltoside, the subject experienced pruritic rash. There was no involvement of mucous membranes or fever. The event had a duration of 11 days and the patient made full recovery. No SAR was observed in the iron sucrose group.

In this trial, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of IV iron isomaltoside in comparison to iron sucrose in gynecological patients with IDA. The women were primarily pre‐menopausal with a history of menorrhagia but were otherwise healthy.

For the primary endpoint, the proportion reaching a Hb increase from baseline of ≥2 g/dL at any time between week 1 and 5, both non‐inferiority and superiority was confirmed for iron isomaltoside compared to iron sucrose. Furthermore, a significantly shorter time to Hb increase ≥2 g/dL was observed with iron isomaltoside. For all biochemical efficacy parameters (Hb, s‐ferritin, and TSAT) measured, more rapid and/or greater improvements were found with iron isomaltoside. These findings are in agreement with results of the main trial.5

QoL improved in both treatment groups during the trial. In a previous trial including women with postpartum hemorrhage, a single dose of iron isomaltoside led to statistically significant differences in fatigue and depression scores, as well as in hematological and iron parameters, all favoring iron isomaltoside when compared with standard medical care.6

Treatment with iron isomaltoside and iron sucrose was generally well tolerated with <1% SARs.

In conclusion, iron isomaltoside was more effective than iron sucrose in ensuring a rapid improvement in Hb and other iron‐related parameters. Larger doses of iron isomaltoside can be administered within a shorter time to achieve full iron correction. Iron isomaltoside administration was well tolerated in gynecological patients with IDA.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Lars L. Thomsen is employed by Pharmacosmos A/S, and the investigators/institutions received a fee per patient. Richard Derman has been a consultant for Pharmacosmos A/S. Michael Auerbach has received research funding from Pharmacosmos A/S and AMAG Pharmaceuticals and has consulted for Pharmacosmos A/S, AMAG Pharmaceuticals, and Luitpold Pharmaceuticals. Maureen M. Achebe served on a scientific advisory board for AMAG Pharmaceuticals. Eloy Roman and Gioi N. Smith‐Nguyen have no further conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the investigators and trial personnel for their contribution to the trial, the statistical support from Jens‐Kristian Slott Jensen, Slott Stat, and the medical writing assistance of Eva‐Maria Damsgaard Nielsen in editing the manuscript. Eva‐Maria Damsgaard Nielsen is employed at Pharmacosmos A/S.

Funding information Pharmacosmos A/S

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO Global database on anaemia, Center for Disease Control and Prevention . Worldwide Prevalence of Anaemia 1993–2005. Spain: World Health Organization; 2008. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43894/9789241596657_eng.pdf;jsessionid=DE0809C8C8FB930B8F4B38088937C629?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dignass AU, Gasche C, Bettenworth D, et al. European consensus on the diagnosis and management of iron deficiency and anaemia in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9(3):211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease, 2012, Vol.2 http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/pdf/KDIGO-Anemia%20GL.pdf. Accessed December 21, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gasche C, Berstad A, Befrits R, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of iron deficiency and anemia in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(12):1545–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Derman R, Roman E, Modiano MR, Achebe MM, Thomsen LL, Auerbach M. A randomized trial of iron isomaltoside versus iron sucrose in patients with iron deficiency anemia. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(3):286–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holm C, Thomsen LL, Norgaard A, Langhoff‐Roos J. Single‐dose intravenous iron infusion or oral iron for treatment of fatigue after postpartum haemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial. Vox Sang. 2017;112(3):219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]