Abstract

Background

Sparse population-based data are available on the prevalence and etiology of chronic liver disease (CLD) in Italy. The study aims to assess the role of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in CLD according to age, gender and ethnicity.

Methods

Clinically diagnosed CLD in the general population aged 20–59 years in the Veneto Region (North-Eastern Italy) were identified through the Adjusted Clinical Groups System, by record linkage of the archive of subjects enrolled in the Regional Health System with Hospital Discharge Records, Emergency Room visits, Chronic disease registry for copayment exemptions, and the Home care database. Age-standardized prevalence rates (PR) were computed in Italians and immigrants, based on country of citizenship.

Results

Overall 22,934 subjects affected by CLD in 2016 were retrieved, 21% related to HBV and 43% to HCV infection. The prevalence of HCV-related CLD was higher in males, peaking at 50–54 years (males = 11/1000; females = 4/1000). The PR of HBV-related CLD was almost negligible in the Italian population (1/1000), and higher among immigrants, especially from East Asia (males = 17/1000; females = 11/1000) and Sub-Saharan Africa (males = 13/1000; females = 10/1000).

Conclusion

Specific population sub-groups identified by age, gender, and ethnicity, were demonstrated to be at increased risk, and these trends are in line with global epidemiological patterns of viral hepatitis.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Infectious disease, Chronic liver disease, Viral hepatitis, Immigrants

1. Introduction

Chronic liver disease (CLD) represents an important medical and public health problem worldwide and is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality [1]. There is a large degree of geographic variation in the burden of CLD, depending on the prevalence of causative factors such as viral hepatitis infection, including hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, alcohol consumption, diabetes and the metabolic syndrome [2].

The most common etiologic factor for CLD in Italy has traditionally been represented by HCV, especially in the elderly population, due to a widespread diffusion associated with unsafe medical procedures after World War II [3]. The effect of such epidemic is now vanishing as shown by a reduced proportion of HCV-related liver cirrhosis in Italy in the last decades [4]. Also mortality from liver cirrhosis and liver cancer is currently decreasing in Italy, mostly due to a fall in the transmission of HCV and universal vaccination against HBV [5].

However, several factors could reverse this favorable trend especially among young and middle-aged adults. An increase in HCV-related mortality among males aged 50–54 years has been recently reported in Northern Italy [6]. The role of HBV infection, in spite of very high vaccination coverage of the native population under 35 years, might increase due to massive immigration from countries with intermediate or high endemicity [7]. Lastly, an increased occurrence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is expected, due to the ongoing epidemic of diabetes and the metabolic syndrome [8].

The Veneto Region (Northeastern Italy, about 4.9 million inhabitants) is a highly industrialized area, having one of the highest prevalence of resident foreign population in Italy distributed across many countries of origin, mainly Eastern Europe, Asia, and Africa [9]. Few population-based studies on the burden of liver diseases have been carried out in Italy [10]. Aim of the study is to investigate the prevalence of CLD, and the role of hepatitis B and C virus infection across population groups stratified by age, gender and ethnicity in Veneto by means of linked electronic health archives.

2. Methods

All legal residents in the Veneto Region aged 20–59 years were included in the study. The archive of subjects enrolled in the Regional Health System was linked with routinely available electronic health records for the year 2016: Hospital Discharge Records, Emergency Room visits, Chronic disease registry for copayment exemptions, Home care visits. To assure a more complete retrieval of chronic conditions, hospital discharge records were investigated also for the period 2011–2015. By linkage of the above archives, the Johns Hopkins University Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) System v.10.0.2 has been adopted to identify patients affected by CLD, using the specific Expanded Diagnosis Clusters (EDC) GAS05 [11,12]. CLD was then classified by aetiology using the following International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition-Clinical Modification codes: HBV-related CLD (070.2x, 070.3x, 070.42, 070.52), HCV-related CLD (070.41, 070.44, 070.51, 070.54, 070.7x), alcohol –related CLD (571.0 and 571.3, or CLD in the presence of other alcohol-related diagnoses: 291.x, 303.x, 305.0, 357.5, 425.5, 535.3, 5710, 5711, 5712, 5713, 980.0, V11.3), biliary cirrhosis (571.6). All analyses were carried out on routinely collected health records submitted to a standardized anonymization process that assigns to each subject a unique code allowing record linkage between electronic archives, without any possibility of back-retrieving his identity; no informed consent was necessary.

Data on age, gender, and country of citizenship of the study population was obtained from the archive of subjects enrolled in the Regional Health System. The prevalence of CLD with different etiologies was compared across gender, 5-year age groups, and immigrant groups classified according to country of citizenship. Immigrants can obtain Italian citizenship by marriage or –on demand-after a minimum of 10 consecutive years of legal residence; their children - if born in Italy-can obtain it after their 18th birthday. As a consequence, the immigrant population identified by citizenship includes second generation immigrants (mostly limited to pediatric age groups), and excludes subjects born abroad who acquired the Italian citizenship and are classified as Italians. To deal with larger numbers and to compare with findings from previous studies, countries of citizenship were grouped by area of origin based on macro-geographical regions [9]. Since electronic health data are less complete in older age classes, and the elderly immigrant population is small, comparisons were restricted to residents aged 20–59 years, to deal with a more homogeneous adult population. According to previous studies carried out in the Veneto Region [9], specific analysis on immigrants from Central-South America and from high income countries were not performed due to low numbers. Since within the adult population immigrant groups have different age structures, age-standardized prevalence rates (World Standard Population [13]) were computed, with 95% confidence intervals obtained by means of the method based on the gamma distribution [14].

3. Results

The study population included 2,604,575 residents aged 20–59 years; immigrants were 351,530 and accounted for 13.5% of study subjects. Within the immigrant population, the most represented group was from Eastern Europe (55% out of all immigrant residents), followed by North Africa (11%), South Asia (the Indian sub-continent, 10%), Sub-Saharan Africa (9%), and other Asian countries (8%, mainly East Asia, including China and the Philippines).

Overall 22,934 subjects (63.7% males) affected by CLD were identified by linked electronic health archives in 2016. The overall prevalence of CLD was 11.1/1000 population (95% Confidence Interval 10.9–11.2) among males and 6.4/1000 (6.3–6.5) among females. Table 1 shows the distribution by gender and aetiology; the latter was coded according to non-mutually exclusive categories (2.7% of patients being classified into multiple etiologies). The most common cause of CLD was HCV infection (43.1%), followed by HBV (20.7%) and alcohol (11.3%). The proportion of CLD related to HCV infection was higher in males, and the proportion related to HBV infection was larger in females. About one out four patients (25.4%) could not be attributed to any of the above categories.

Table 1.

Distribution of chronic liver disease by gender and aetiology (according to non-mutually exclusive categories). Residents aged 20–59 years, Veneto Region (Italy), 2016.

| Males |

Females |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| All chronic liver diseases | 14600 | 8334 | ||

| HBV-related | 2800 | 19% | 1951 | 23% |

| HCV-related | 6608 | 45% | 3281 | 39% |

| Alcohol-related | 1956 | 13% | 636 | 8% |

| Biliary cirrhosis | 131 | 1% | 369 | 4% |

| Unknown aetiology | 3579 | 25% | 2248 | 27% |

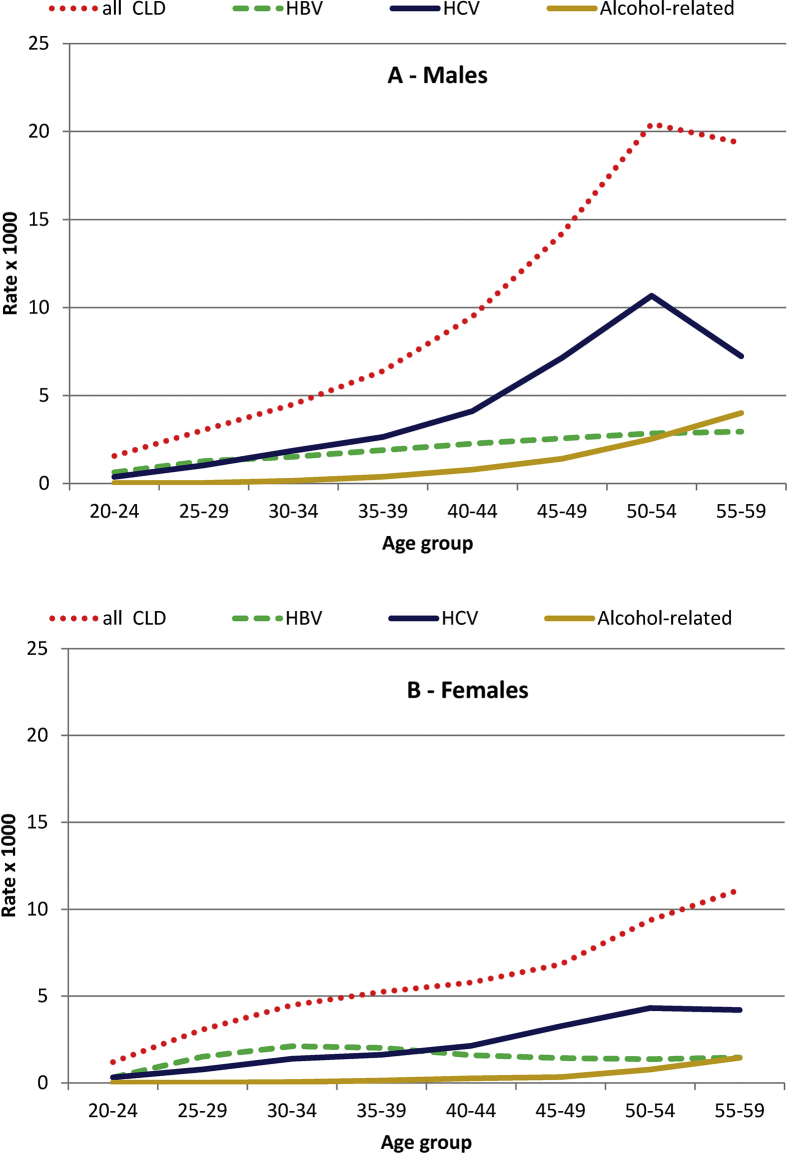

The prevalence of CLD among males increased with age until 50–54 years, with a slight decline in the subsequent age class (Fig. 1); such specific pattern was due to the distribution of HCV-related CLD, reaching a peak of 11/1000 in males aged 50–54. The prevalence of HBV showed a constant increase with age and the prevalence of alcohol-related CLD a steep increase with age. Among females, a lower overall prevalence of CLD, a less clear peak in HCV-related CLD (4/1000 in subjects aged 50–54 years), and a steady prevalence of HBV-related CLD across age classes were observed.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence (per 1000 population) of chronic liver disease (CLD) in males (A) and females (B) by age and aetiology. Veneto Region (Italy), 2016.

The overall prevalence of CLD was higher in immigrants than in Italians, except for older males, where rates were slightly higher in the native population (Table 2). The prevalence of HBV-related CLD was negligible among Italian citizens aged <40 years, showing only a moderate increase in older age classes. Among immigrants compared to Italians prevalence rates were at least ten times higher in younger subjects (20–39 years), and 3–5 fold higher in middle-aged adults (40–59 years). Notably, immigrants accounted for as much as 42% of HBV-related CLD in males (1179/2800) and 56% in females (1083/1951). The increase of prevalence of HCV-related CLD with age was steeper in Italians than immigrants among males; among females, the rates were higher in immigrants in all age classes.

Table 2.

Italian and immigrant population aged 20–59 years in the Veneto region (Italy): age-specific and crude prevalence rates of all chronic liver diseases (CLD), HBV- and HCV-related CLD.

| Age Class | n |

rate per 1000 population |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italians | Immigrants | Italians | Immigrants | ||

| Males | |||||

| All CLD | |||||

| 20–29 yrs | 293 | 261 | 1.4 | 7.3 | |

| 30–39 yrs | 1060 | 529 | 4.6 | 9.7 | |

| 40–49 yrs | 4157 | 713 | 11.7 | 14.1 | |

| 50–59 yrs | 7151 | 436 | 20.2 | 17.5 | |

| Overall 20–59 yrs | 12661 | 1939 | 11.1 | 11.7 | |

| HBV | |||||

| 20–29 yrs | 35 | 194 | 0.2 | 5.4 | |

| 30–39 yrs | 133 | 358 | 0.6 | 6.6 | |

| 40–49 yrs | 548 | 435 | 1.5 | 8.6 | |

| 50–59 yrs | 905 | 192 | 2.6 | 7.7 | |

| Overall 20–59 yrs | 1621 | 1179 | 1.4 | 7.1 | |

| HCV | |||||

| 20–29 yrs | 136 | 33 | 0.7 | 0.9 | |

| 30–39 yrs | 592 | 67 | 2.6 | 1.2 | |

| 40–49 yrs | 2222 | 93 | 6.2 | 1.8 | |

| 50–59 yrs | 3368 | 97 | 9.5 | 3.9 | |

| Overall 20–59 yrs | 6318 | 290 | 5.5 | 1.8 | |

| Females | |||||

| All CLD | |||||

| 20–29 yrs | 255 | 242 | 1.3 | 6.3 | |

| 30–39 yrs | 743 | 666 | 3.3 | 10.7 | |

| 40–49 yrs | 1932 | 597 | 5.6 | 11.4 | |

| 50–59 yrs | 3400 | 499 | 9.8 | 15.1 | |

| Overall 20–59 yrs | 6330 | 2004 | 5.7 | 10.8 | |

| HBV | |||||

| 20–29 yrs | 30 | 184 | 0.2 | 4.8 | |

| 30–39 yrs | 147 | 444 | 0.7 | 7.1 | |

| 40–49 yrs | 311 | 293 | 0.9 | 5.6 | |

| 50–59 yrs | 380 | 162 | 1.1 | 4.9 | |

| Overall 20–59 yrs | 868 | 1083 | 0.8 | 5.8 | |

| HCV | |||||

| 20–29 yrs | 100 | 28 | 0.5 | 0.7 | |

| 30–39 yrs | 301 | 134 | 1.3 | 2.1 | |

| 40–49 yrs | 924 | 165 | 2.7 | 3.2 | |

| 50–59 yrs | 1414 | 215 | 4.1 | 6.5 | |

| Overall 20–59 yrs | 2739 | 542 | 2.5 | 2.9 | |

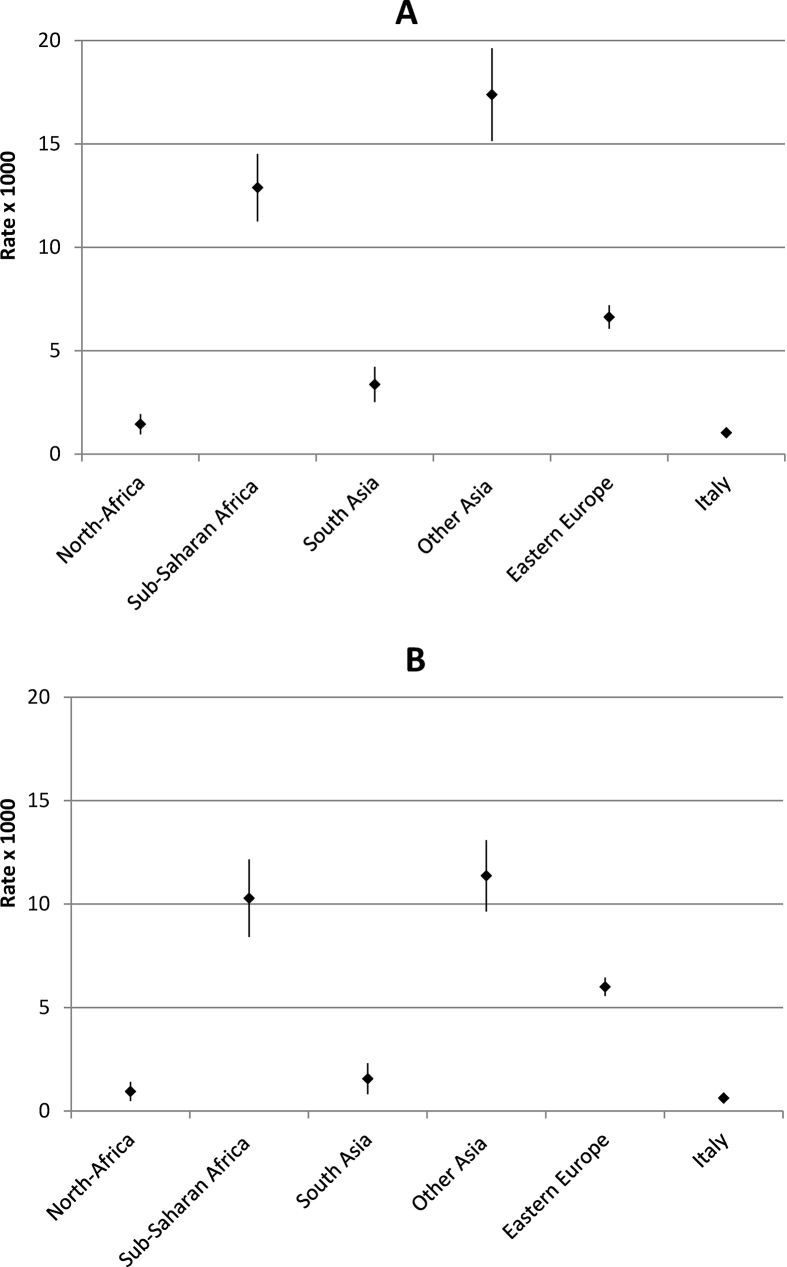

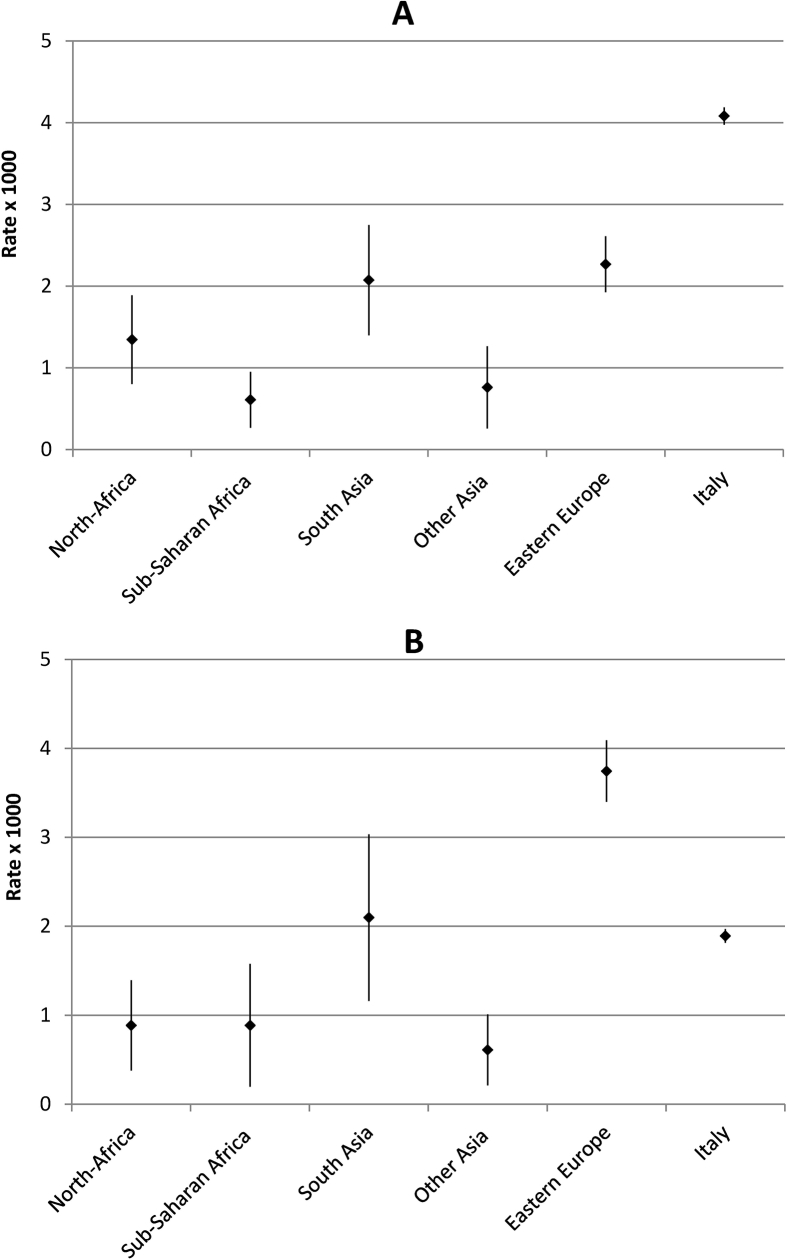

Age-standardized prevalence rates of HBV and HCV-related CLD by area of provenience are shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. The highest prevalence rates of HBV-related CLD were observed among immigrants from other Asian countries (mainly East Asia, males 17/1000; females 11/1000) and Sub-Saharan Africa (males 13/1000; females 10/1000), with the lowest figures among Italians (about 1/1000 in both genders). As regards HCV, among males the highest prevalence was observed in Italian residents; among females the highest rates were registered in immigrants from Eastern Europe (4/1000) followed by South Asians and Italians (2/1000).

Fig. 2.

Standardized prevalence rates with 95% confidence intervals (per 1000 population; World Standard Population) of HBV-related chronic liver disease among males (A) and females (B) aged 20–59 years in Italians and immigrants by area of provenience. Veneto Region (Italy), 2016.

Fig. 3.

Standardized prevalence rates with 95% confidence intervals (per 1000 population; World Standard Population) of HCV-related chronic liver disease among males (A) and females (B) aged 20–59 years in Italians and immigrants by area of provenience. Veneto Region (Italy), 2016.

4. Discussion

The prevalence of CLD in North-Eastern Italy displays great variability among young and middle-aged adults according to age, gender and ethnicity.

The most common risk factor for CLD remains HCV infection. Data collected in the past decades showed that Italy was affected by the highest prevalence of HCV infection within Europe, with a steep increase with age and higher rates in Southern regions [15]. More recent studies suggested that HCV prevalence was decreasing in Italy [4, 16, 17], as well as in all Europe [18], due to the vanishing of the most affected older birth cohorts. However, seroprevalence surveys demonstrated a bimodal distribution of HCV infection both in Northern and in Southern Italy [17, 19, 20], with a minor peak in younger subjects and a higher one in the elderly. These findings suggest the occurrence of two epidemic waves of HCV infection in Italy: the first in the 1950s, due to unsafe medical procedures, and the second one in young people in the late 1970s and in the 1980s, due to the diffusion of intravenous drug use [3]. Such second epidemic wave was confirmed by analyses of Italian death certificates, with an exponential increase of HCV-related mortality with age, and a further peak observed in the 50-54-year age-group especially among males [21]. This second wave can also explain the increase in HCV-related mortality observed from 2008-2012 to 2013–2016 among middle-aged males in the Veneto Region [6]. A similar finding was reported in the US, where HCV infection mostly affected baby boomers, and HCV-related mortality was steadily increasing [22]. Also in Europe most HCV-infected patients are between 45 and 60 years old, indicating a possible target birth-cohort group for screening programs [18]. Overall, these findings suggest that the HCV burden in Italy is shifting from the elderly population to subjects born in the 1960s, resulting in increasing HCV-related morbidity and mortality among middle-aged adults. The availability of directing acting antivirals (DAA) for HCV treatment is expected not only to reduce the progression of liver disease and consequently mortality among HCV patients, but also the burden of HCV infection at the population level [23]. In Italy, treatment with DAA became available in 2015 and was initially restricted to patients with advanced liver disease; only recently (2017) it was made available to patients with less severe disease stages [24].

The epidemiological scenario of HBV- and HCV-related CLD in Italy is also influenced by mass immigration from areas of the world at high prevalence of viral hepatitis [24]. As regards HCV, all immigrant groups are at lower prevalence than the Italian population, except for women from Eastern Europe. This gender effect might partly be an artifact due to higher diagnostic pressure among females of childbearing age, with a possible underestimation of HCV rates among Eastern European males. In fact, awareness of chronic HBV or HCV is low in all populations but among migrants it tends to be even lower; in Europe, Romania (the most common country of origin of immigrants to Italy) is among the nations with the highest reported HCV prevalence rates [25].

After the availability of highly effective therapies for HCV, the role of HBV has become overshadowed in public health prioritization [26]. HBV infection in Italy has shown a progressive reduction in prevalence over the past decades [7], and now its burden among native young adults is negligible. By contrast, almost all immigrant groups are disproportionally affected by HBV-related CLD. Rates observed in different immigrant groups are consistent with seroprevalence surveys carried out among undocumented immigrants in Southern Italy [27], and reflect the global epidemiology of the disease: the highest prevalence was found among subjects from Eastern Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, followed by immigrants from countries usually considered at intermediate endemicity in South Asia and Eastern Europe [28, 29]. It must be remarked that in high endemicity countries the most common routes of acquiring infection are perinatal transmission and infection during pre-school years, and for this reason WHO recommends universal birth-dose vaccination [25]; however among countries with the greatest number of infected children, only China displays a high timely birth dose coverage [26]. In the Veneto region, about half of the burden of HBV in the adult population is currently accounted for by immigrants, similarly to reports from Northern Europe [30].

Some limits of the study should be taken into account: first, only clinically diagnosed CLD registered within health records could be tracked, with an underestimation of the prevalence probably more pronounced among the immigrant population. A second limit is the use of citizenship to identify immigrant groups instead of country of birth, or of more specific features such as language; however, citizenship was the most reliable information to identify ethnic groups in health records. Restricting analyses to the adult population allowed to deal with more accurate diagnoses, to more properly compare the immigrant with the native population, and to avoid a further underestimation of rates among immigrants, more probable in older age classes, mainly due to unregistered remigration to the country of origin [9]. Third, since CLD was classified according to ICD9-CM codes registered in patients' health records, no information whether HBV or HCV infection was defined on serological markers or viral loads was available. Lastly, the use of routinely collected clinical data on CLD aetiology may provide valuable results for identifying HBV- and HCV-related, but not alcohol-related CLD. Indeed, both hospital-based and population-based studies in Italy found a minor role of alcohol as a cause of CLD [4, 10], which is likely an underestimate, as shown by studies assessing subjects’ history of alcohol intake through interviews with standardized questionnaires [31]. Since alcohol intake is often poorly evaluated in the current clinical practice, some CLD cases with unknown aetiology are likely due to alcohol intake; moreover, in subjects with combined viral hepatitis infection and high alcohol intake, the diagnosis in clinical records probably mention only the viral aetiology [10].

5. Conclusion

In spite of study limits, the record linkage among electronic health databases allowed us to provide a comprehensive picture of the distribution of CLD among young and middle-aged adults in a vast area in North-Eastern Italy. The use of data routinely collected during the delivery of health care allowed us to obtain population-based figures, avoiding bias due to referral patterns typical of multicenter studies. Moreover, data on the immigrant population were not retrieved within highly selected groups, e.g. asylum seekers or undocumented immigrants, but represented a large diverse population from several different world areas, with full access to regional health services. Although rates were underestimated since only clinically-diagnosed CLD could be tracked, specific population sub-groups were identified according to age, gender, and ethnicity at higher prevalence of HBV and HCV-related CLD. Such groups, often under-represented in surveys of the general population, should be the focus of more detailed studies in order to design targeted preventive, testing, and treatment strategies.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Ugo Fedeli, Francesco Donato: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Francesco Avossa, Angela De Paoli: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Eliana Ferroni: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Maria Chiara Corti: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Tsochatzis E.A., Bosch J., Burroughs A.K. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2014;383:1749–1761. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1151–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puoti M., Girardi E. Chronic hepatitis C in Italy: the vanishing of the first and most consistent epidemic wave. Dig. Liver Dis. 2013;45:369–370. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stroffolini T., Sagnelli E., Gaeta G.B., Sagnelli C., Andriulli A., Brancaccio G. Characteristics of liver cirrhosis in Italy: evidence for a decreasing role of HCV aetiology. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2017;38:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fedeli U., Avossa F., Guzzinati S., Bovo E., Saugo M. Trends in mortality from chronic liver disease. Ann. Epidemiol. 2014;24:522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fedeli U. Increasing mortality associated with the more recent epidemic wave of Hepatitis C virus infection in Northern Italy. J. Viral Hepat. 2018 Mar 13 doi: 10.1111/jvh.12893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sagnelli E., Sagnelli C., Pisaturo M., Macera M., Coppola N. Epidemiology of acute and chronic hepatitis B and delta over the last 5 decades in Italy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7635–7643. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saracco G.M., Evangelista A., Fagoonee S., Ciccone G., Bugianesi E., Caviglia G.P. Etiology of chronic liver diseases in the Northwest of Italy, 1998 through 2014. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8187–8193. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i36.8187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedeli U., Avossa F., Ferroni E., Schievano E., Bilato C., Modesti P.A., Corti M.C. Diverging patterns of cardiovascular diseases across immigrant groups in Northern Italy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018;254:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zani C., Pasquale L., Bressanelli M., Puoti M., Paris B., Coccaglio R. The epidemiological pattern of chronic liver diseases in a community undergoing voluntary screening for hepatitis B and C. Dig. Liver Dis. 2011;43:653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starfield B., Kinder K. Multimorbidity and its measurement. Health Policy. 2011;103:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corti M.C., Avossa F., Schievano E., Gallina P., Ferroni E., Alba N. A case-mix classification system for explaining healthcare costs using administrative data in Italy. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018;54:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad O., Boschi-Pinto C., Lopez A., Murray C., Lozano R., Inoue M. World Health Organization; 2001. Age Standardization of Rates: a New WHO Standard. GPE Discussion Paper Series: n. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fay M.P., Feuer E.J. Confidence intervals for directly adjusted rates: a method based on the gamma distribution. Stat. Med. 1997;16:791–801. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970415)16:7<791::aid-sim500>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . ECDC; Stockholm: 2010. Hepatitis B and C in the EU Neighbourhood: Prevalence, burden of Disease and Screening Policies. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guadagnino V., Stroffolini T., Caroleo B., Menniti Ippolito F., Rapicetta M., Ciccaglione A.R. Hepatitis C virus infection in an endemic area of Southern Italy 14 years later: evidence for a vanishing infection. Dig. Liver Dis. 2013;45:403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andriulli A., Stroffolini T., Mariano A., Valvano M.R., Grattagliano I., Ippolito A.M. Declining prevalence and increasing awareness of HCV infection in Italy: a population-based survey in five metropolitan areas. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018 Feb 20;(18):30072–30074. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.02.015. pii: S0953-6205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papatheodoridis G.V., Hatzakis A., Cholongitas E., Baptista-Leite R., Baskozos I., Chhatwal J. Hepatitis C: the beginning of the end-key elements for successful European and national strategies to eliminate HCV in Europe. J. Viral Hepat. 2018;25(Suppl 1):6–17. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fabris P., Baldo V., Baldovin T., Bellotto E., Rassu M., Trivello R. Changing epidemiology of HCV and HBV infections in Northern Italy: a survey in the general population. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2008;42:527–532. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318030e3ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polilli E., Tontodonati M., Flacco M.E., Ursini T., Striani P., Di Giammartino D. High seroprevalence of HCV in the Abruzzo Region, Italy: results on a large sample from opt-out pre-surgical screening. Infection. 2016;44:85–91. doi: 10.1007/s15010-015-0841-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fedeli U., Grande E., Grippo F., Frova L. Mortality associated with hepatitis C and hepatitis B virus infection: a nationwide study on multiple causes of death data. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017;23:1866–1871. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i10.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ly K.N., Hughes E.M., Jiles R.B., Holmberg S.D. Rising mortality associated with hepatitis C virus in the United States, 2003-2013. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;62:1287–1288. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salmon D., Mondelli M.U., Maticic M., Arends J.E., ESCMID Study Group for Viral Hepatitis The benefits of hepatitis C virus cure: every rose has thorns. J. Viral Hepat. 2018;25:320–328. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viganò M., Perno C.F., Craxì A. AdHoc (advancing hepatitis C for the optimization of cure) working party. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in Italy: a consensus report from an expert panel. Dig. Liver Dis. 2017;49:731–741. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma S., Carballo M., Feld J.J., Janssen H.L. Immigration and viral hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2015;63:515–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polaris Observatory Collaborators Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;3:383–403. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coppola N., Alessio L., Gualdieri L., Pisaturo M., Sagnelli C., Minichini C. Hepatitis B virus infection in undocumented immigrants and refugees in Southern Italy: demographic, virological, and clinical features. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2017;6:33. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0228-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . ECDC; Stockholm: 2016. Epidemiological Assessment of Hepatitis B and C Among Migrants in the EU/EEA. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanaway J.D., Flaxman A.D., Naghavi M., Fitzmaurice C., Vos T., Abubakar I. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;388:1081–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30579-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marschall T., Kretzschmar M., Mangen M.J., Schalm S. High impact of migration on the prevalence of chronic hepatitis B in The Netherlands. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008;20:1214–1225. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32830e289e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellentani S., Saccoccio G., Costa G., Tiribelli C., Manenti F., Sodde M. Drinking habits as cofactors of risk for alcohol induced liver damage. The Dionysos Study Group. Gut. 1997;41:845–850. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.6.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]