ABSTRACT

Introduction: To restore full function following nerve crush injuries is critical but challenging. In an attempt to develop a viable therapy, we evaluated the effect of rat adipose‐derived stem cells (rASC) in 2 different settings of a sciatic crush injury model. Methods: In the first group, after 14 days of nerve crush injury, rASCs were injected distal to the lesion under ultrasound guidance. In the other group, alleviation of compression through clip removal (CR) was combined with epineural injection of rASCs. Gait analyses, MRI, gastrocnemius muscle weight ratio (MWR), and histomorphometry were performed for outcome analysis. Results: CR combined with rASC injection resulted in less muscle atrophy, as evidenced by MWR. These findings are further supported by better functional and anatomical outcomes. Discussion: Animals treated with CR and epineural stem cell injection showed enhanced anatomical and functional recovery. Muscle Nerve 58: 566–572, 2018

Keywords: adipose stem cell, axonal regeneration, nerve crush injury, nerve repair, ultrasound‐guided cell injection

Abbreviations

- ASC

adipose‐derived stem cell

- CI

confidence interval

- CM

culture medium

- CR

clip removal

- drASC

differentiated rat ASC

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- E

experimental

- FA

fractional anisotropy

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FD

fiber density

- hASC

human ASC

- ITS

intermediate toe spread

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cell

- MT

myelin thickness

- MWR

muscle weight ratio

- N

normal

- PL

print length

- rASC

rat ASC

- SC

Schwann cell

- SFI

sciatic functional index

- SVF

stromal vascular fraction

- TS

toe spread

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Severe nerve injury has a devastating impact on a patient's quality of life.1 Although much knowledge exists on the mechanisms of injury and regeneration, there are currently no reliable treatment options that ensure full functional recovery.2 It has been reported that complete recovery of an acutely compressed nerve can take weeks to years.2

Sciatic nerve crush is a well‐established model for the studies of acute neuropathy.3 Nerve damage after crush injury is induced by direct external pressure itself and ischemia when the crushing force exceeds the capillary perfusion pressure.4 Usually, nerve crush injury is less severe than nerve transection injury because the basement membrane of Schwann cells (SC) covering the nerve fascicles and fibers is anatomically intact and enables SCs to provide pathways to guide the regeneration of axons.4 After injury to the sciatic nerve, SCs and macrophages rapidly remove myelin debris and produce extracellular matrix molecules, chemokines, inflammatory cytokines, and proteolytic enzymes as well as a number of growth factors that play crucial roles in axonal regeneration and neuronalsurvival.5

In a study reported by Mackinnon and Dellon,6 20%–40% of the patients achieved very good recovery after nerve repair, but few injuries recovered fully. A recent case‐controlled study compared the outcomes of nerve surgery in patients with isolated peripheral compression versus those with double crush syndrome treated with peripheral nerve and cervical spine operations. At a minimum of 18 months after peripheral nerve surgery, it was shown that the double crush group exhibited a greater frequency of persistent signs of nerve irritability (47%) and muscle weakness (53%) compared with the control group (31% and 20%, respectively).7

Cell transplantation has gained wide interest for treating nerve injuries.8 In recent years, much attention has been paid to adipose‐derived stem cells (ASC). They represent a readily available source for the isolation of potentially useful stem cells and, thus, are very attractive for tissue engineering purposes.9 The purpose of this study is to test the hypothesis that, in the nerve crush injury model, clip removal (CR; nerve decompression) with epineural rat ASC (rASC) injection results in a superior outcome compared with CR with sham injection or rASC injection only without CR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

The experimental group design and time points were chosen on the basis of our previous reports and experience.8, 10, 11, 12 We created a crush injury using a polymeric ligating clip on the left sciatic nerve of 56 female Sprague‐Dawley rats. All the following experiments were conducted after 2 weeks of chronic crush injury. Animals were randomized into 4 groups with 2 end‐points, 28 and 42 days.

ASC: an ultrasound‐guided injection of 0.5 × 106 rASCs suspended in 25 μl of culture medium (CM; Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium, 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 1% penicillin/streptomycin) was performed in the epineurium just distal to the clip

CM: an ultrasound‐guided injection of 25 μl of CM was performed at the same location.

CR ASC: the clip was removed, and 0.5 × 106 rASC suspended in 25 μl of CM was injected at the same location

CR CM: the clip was surgically removed, and 25 μl of CM was injected in the epineurium at the lesion site

The crushed area was subsequently marked with a single epineural suture (Ethilon 8‐0; Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA).

Gait analyses with calculation of the sciatic functional index (SFI) were conducted by using a walking track at 14, 28, and 42 days. Postmortem imaging with a 3‐Tesla MRI machine was performed. Fractional anisotropy (FA), a measure of fiber integrity, was obtained for the proximal and distal part of the lesion and compared with the contralateral nerve. The gastrocnemius muscle weight ratio (MWR) was calculated, and histomorphometric analyses were performed.

Experimental Animals

All experiments were performed on 8‐week‐old female Sprague–Dawley rats weighting approximately 250 grams (Harlan Laboratories BV, The Netherlands). The local veterinary commission (No. 2672) and the cantonal veterinary office approved our study. All experiments were conducted by following strict guidelines and ethical standards. The animals were euthanized at the end of the study by using a CO2 gas chamber.

Isolation and Culture of rASCs and PKH Labeling

Fat tissue was harvested and processed from donor animals prior to the start of the surgical interventions as previously described13 to obtain a sufficient number of transplantable cells. Some of the rASCs were pretreated with the PKH26 Red Fluorescent Cell Linker kit (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). PKH26‐pretreated cells were transplanted for long‐term in vivo cell tracking in 1 animal per group. This linker is a yellow‐orange cell fluorescent dye incorporated into lipid regions of the cellmembrane.14, 15 An aqueous solution (Diluent C; Sigma‐Aldrich) was used to optimize the labeling process, enhancing dye solubility and staining efficiency while maintaining cell viability.16 The cells were washed with a serum‐free medium because the serum proteins and lipids also bind the dye. After having been washed, the rASCs were suspended in Diluent C, and the PKH26 ethanolic dye solution was promptly added. Serum was added after 2 min to stop the staining process (FBS; Gibco, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). The cells subsequently underwent centrifugation at 1,500 rpm to be resuspended in fresh CM after several rinses with CM.

Microsurgical Procedure

All operations were performed by the same surgeon, as described earlier.8, 10 The sciatic nerve was freed by using microsurgical scissors over a distance of 1 cm and then compressed with a polymer ligating clip approximately 1 cm distal to the intervertebral foramen (Weck Hem‐o‐lok polymer ligation system, Teleflex Medical, Morrisville, NC, USA), similarly to previous studies (Supp. Info. Fig. 1).17, 18 The site was rinsed with sterile saline solution, the muscle and skin layers were sutured with absorbable Vicryl 4‐0 (Ethicon), and the wound was disinfected with Betadine (Mundipharma Medical, Hamilton, Bermuda). After 2 weeks, therapy was initiated as described earlier. An insulin 30 gauge needle (Sterican; B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) was used for all injections. The volume and number of rASCs used were based on our previous experiences.8, 10, 19

Ultrasound Guided Injections

An ultrasound system combined with a high‐frequency linear transducer (Flex Focus 400 exp; BK Ultrasound, Peabody, MA, USA) was used to guide the injections. The scans were acquired in B‐mode with a frequency of 18 MHz. Under isoflurane anesthesia, the sciatic nerve was localized with ultrasound imaging. The nervous bundle could easily be found lateral to the femur on the left thigh of the rat. The vessels were identified by using the Doppler probe in color modes to avoid inadvertent injury. After identification of the clip, rASCs or CM alone was injected distally. The injection site was visually confirmed via a slight swelling of the nerve on the monitor screen.

Histomorphometry

We carried out a histomorphometrical assessment of the semithin osmium tetroxide‐p‐phenylenediamine‐stained cross‐sections. The observer was blinded to the experimental groups and explanted tissue samples. Digital pictures of the representative fields of the myelinated nerve areas were taken by using a light photomicroscope (BX43F; Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA) at × 10 and ×40. The pictures were processed in ImageJ 1.48 (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) to quantify fiber density (FD) and myelin thickness (MT). The number of nerve fibers per 0.01 mm2 was counted to obtain the FD. Myelin thickness calculated by using the following equation: difference between the fiber diameter and axonal diameters divided by 2. The ratio of the MT and the FD was calculated by dividing the values from the distal part by the values from the proximal part.

Explantation Technique, Cross‐Sections, and Measure of Muscle Atrophy

We proceeded to tissue explantation immediately after acquisition of the MRI data, as previously described.10 In animals with the PKH26‐pretreated cells, a piece of their nerves was snap frozen with Tissue‐Tek O.C.T compound (Sakura Finetek, Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands) in isopentane precooled to −20 °C. Images were acquired with a fluorescence microscope to assess the presence of transplanted cells. Weight measurements of the gastrocnemius muscle on the experimental side (left) and the contralateral side (right) were performed to calculate the MWR. The muscles were weighed on a precision scale (Mettler‐Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland) in 0.1‐mg increments.

MRI With Diffusion Tensor Imaging Sequences

MRI studies were carried out with a human scanner to assess nerve regeneration. Data were acquired by using the 3‐Tesla MAGNETOM Prisma syngo MR D13D scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) combined with the Hand/Wrist 16 coil (sixteen channels; Siemens Healthcare) to accommodate the animal size. At 28 and 42 days after injections and/or removal of the clip, the animals were humanely killed to perform the imaging studies. The diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) sequences were obtained in a transverse plane by using an echo time of 69 ms, a repetition time of 5,700 ms, and a voxel size of 2 × 2 × 2 mm.

A radiologist specializing in DTI who was blinded to the groups processed the DTI sequences in MITK Diffusion open source software (German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany) to calculate FA. The FA value is a measure of fiber integrity. An FA of zero indicates that diffusion is isotropic and going in all directions (unrestricted or equally restricted), whereas an FA of 1 means that diffusion is restricted along 1 axis, which can be seen, for example, in intact nerve fibers. FA values were obtained for the experimental side (left nerve) proximally and distally to the clip and for the contralateral side (right nerve) that served as control.

Gait Analyses With CatWalk

Functional gait analyses were acquired 14 days after the compressive injury to assess the locomotion status of the injured limb before the initiation of treatments. Follow‐up evaluations were then carried out after another 14 and 28 days. The computed walking track Catwalk XT (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands) was used to assess gait parameters, and the SFI was calculated from those data, as previously described.20, 21 Two consecutive runs were acquired under the same conditions for each rat. An observer who was blinded to the study groups manually measured the print length (PL), toe spread (TS, distance between first and fifth digits) and intermediate toe spread (ITS, distance between second and fourth digits) on both experimental (E) and normal limbs (N) to determine the SFI. The software calculates the SFI22 by using the formula SFI = 38.8 (EPL − NPL) / NPL + 109.5 (ETS − NTS) / NTS + 13.3 (EITS − NITS) / NITS − 8.8. An SFI of 0 indicates a normal sciatic function, and an SFI of −100 means that total deficiency could be seen after a complete nerve transection.

Statistical Analysis

The values are shown as mean and SD/SEM from at least 3 animals per group, and all experimental samples were conducted in triplicate. One‐way analysis of variance tests with corresponding post hoc tests (Bonferroni or Tukey; Prism version 5.0 for Windows; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) were used for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Postoperative Outcome of the Animals

All animals undergoing the procedure recovered well from surgery, and no postoperative complications such as an open wound or auto mutilation of the affected limb were noted, thus allowing us to include all study rats in the data.

Histomorphometry

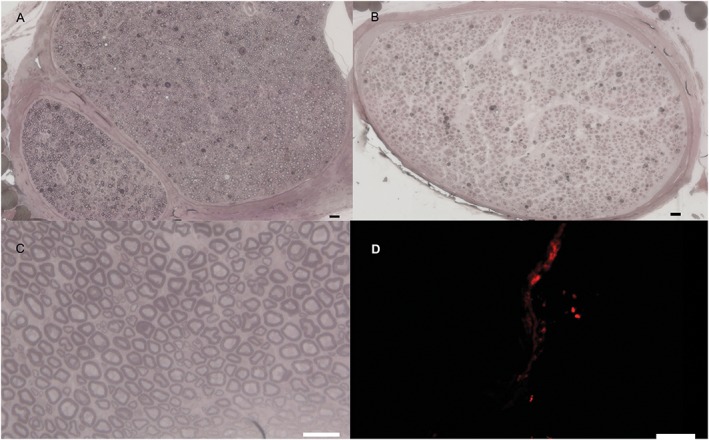

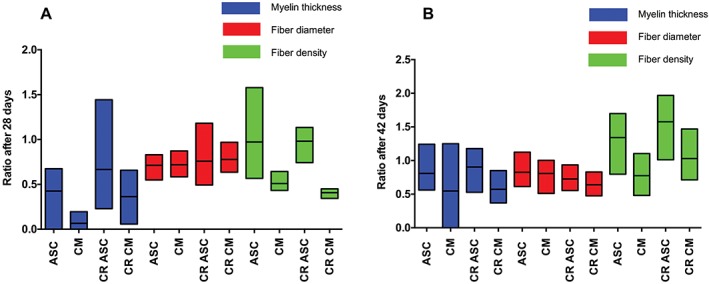

Representative semithin osmium tetroxide‐p‐phenylenediamine‐stained cross‐sections are shown in Figure 1. After 42 days, we successfully confirmed cell viability by using PKH26‐labeled rASCs (Fig. 1D). Semiquantitative analyses after 28 and 42 days are shown in Figure 2. Although there was no significant difference between the groups after 28 and 42 days, MT, fiber diameter, and FD showed the highest ratio in the rASC and CR rASC groups after 28 and 42 days. The CR rASC group showed a higher ratio compared with the rASC group for the MT and FD after 28 and 42 days (0.7 ± 0.4 vs. 0.4 ± 0.2 and 0.98 ± 0.1 vs. 0.97 ± 0.3 after 28 days and 0.9 ± 0.2 vs. 0.8 ± 0.2 and 1.6 ± 0.3 vs. 1.3 ± 0.3 after 42 days, respectively). A lower ratio was found for the CM and CR CM groups after 28 and 42 days, although a relatively high ratio was also observed in the CM group for fiber diameter after 28 and 42 days (0.7 ± 0.1 and 0.8 ± 0.2 after 28 and 42 days, respectively).

Figure 1.

Representative images of semithin osmium tetroxide‐p‐phenylenediamine‐stained cross‐sections. (A) Representative image (×10) of a healthy nerve. (B) Representative image (×10) of a cross‐section of the distal part of the crushed nerve (rat adipose‐derived stem cell [ASC] group after 28 days). (C) Representative image (×40) of a cross‐section of the distal part of the crushed nerve treated with ASCs and clip removal after 28 days. (D) Representative image (×20) of PKH26‐labeled cells 28 days after ASC injection. Scale bars = 20 μm in (A–C); 100 μm in D. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 2.

Floating bars (minimum to maximum, line represents mean) of histomorphometric analyses at 28 (A) and 42 (B) days for each group. The ratio was calculated by dividing the values from the distal part by the values from the proximal part. Statistical adjustments for multiple comparisons showed no statistical significance between clips and their corresponding CR groups at 28 and 42 days. ASC, adipose‐derived stem cell; CM, culture medium; CR, clip removal. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Gastrocnemius MWR

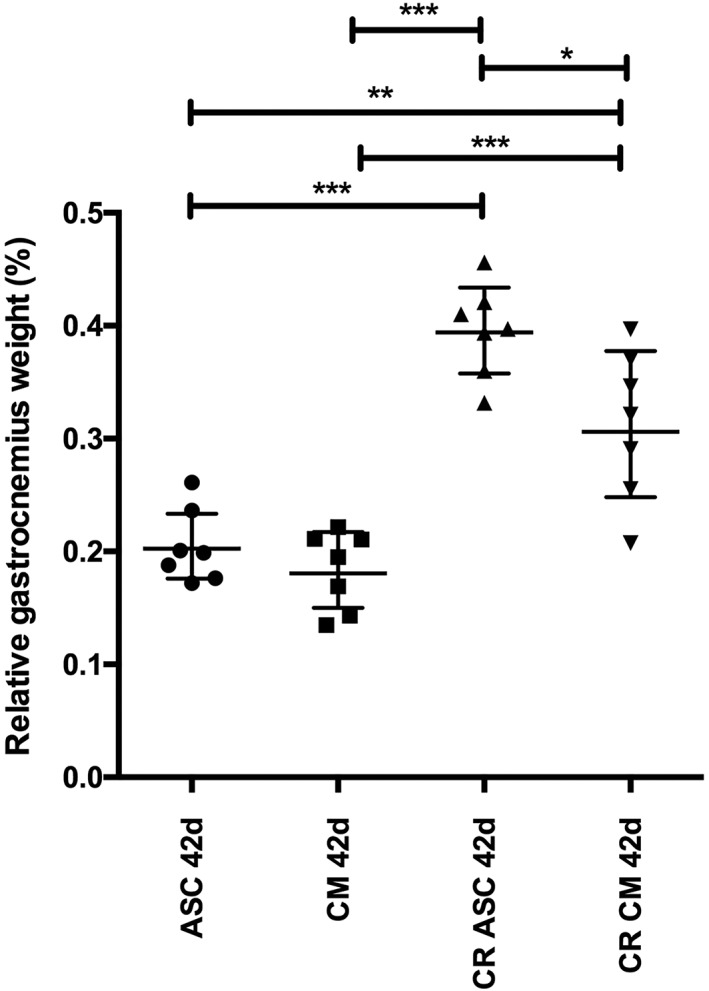

Figure 3 shows the mean MWR with a 95% confidence interval (CI) at 42 days for each group. At 42 days (28 days posttreatment), was 0.21 ± 0.03 for the MWR rASC group, 0.18 ± 0.04 for the CM group, 0.40 ± 0.04 for the CR and rASC group, and 0.31 ± 0.07 for the CR group with CM. There were no significant differences between the rASC and CM‐only groups. However, there was a significant difference between the CR group treated with rASC and the CR group treated with CM, with a mean difference of 0.08 (P < 0.05). Overall, the CR combined with rASC group showed the least muscle atrophy, with ratio values significantly higher than those of the other groups.

Figure 3.

Overall average relative gastrocnemius weight (gastrocnemius MWR) at 42 days for each group. Data are expressed as the mean and 95% CI. There was a significant difference between the CR group treated with ASC (CR ASC) and the CR group treated with CM (CR CM), with a mean difference of 0.08310. *(P) < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001. ASC, adipose‐derived stem cell; CI, confidence interval; CM, culture medium; CR, clip removal; MWR, muscle weight ratio.

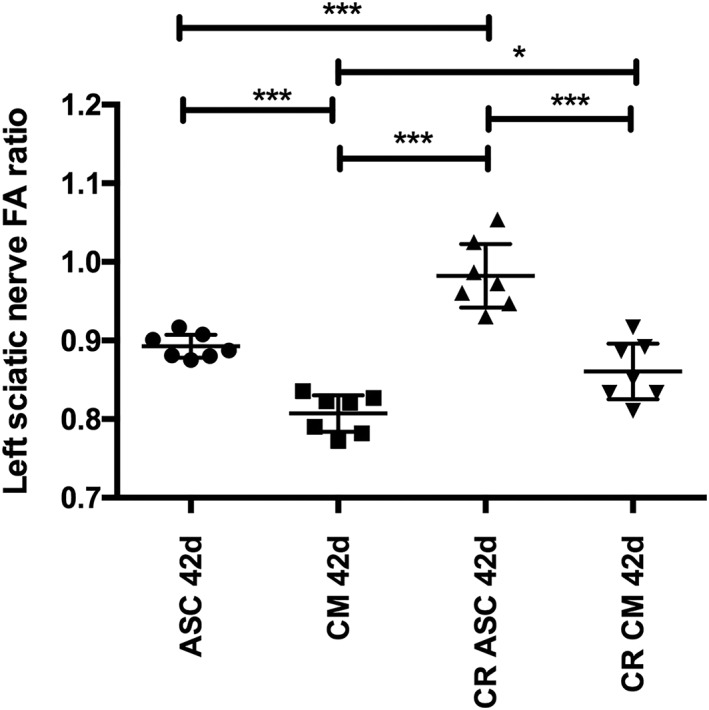

Fractional Anisotropy

The mean FA value for the right sciatic nerve, which served as an internal control, was 0.774 (n = 28) at 28 days and 0.765 (n = 28) at 42 days. The mean FA value for the left sciatic nerve measured proximal to the clip lesion was 0.773 (n = 28) at 28 days and 0.770 (n = 28) at 42 days. As expected, those values were not significantly different. To assess nerve regeneration with the FA values measured distal to the lesion, the ratio of the left distal FA value and the left proximal FA value were obtained (left distal FA/left proximal FA). Figure 4 shows the mean FA ratios with a 95% CI at 42 days for each group. At 42 days (28 days posttreatment), the FA value ratio was 0.893 ± 0.02 for the rASC group, 0.810 ± 0.03 for the CM group, 0.982 ± 0.04 for the CR with rASC group, and 0.861 ± 0.04 for the CR group with CM. The CR combined with rASC group was the group with FA ratio values closest to 1. The rASC‐only and the CR with CM groups showed very similar FA ratio values, with no statistically significant difference between their results. The rASC group FA ratio values were also significantly better than those of the CM‐only group.

Figure 4.

Overall average FA ratios for the left sciatic nerve at 42 days for each group. Data are expressed as mean and 95% CI. The CR group treated with ASC (CR ASC) showed the FA ratio values closest to 1. The ASC and CR CM groups showed very similar FA ratio values, with no statistically significant difference between their results. The ASC group's FA ratio was also superior to that of the CM‐only group. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001. ASC, adipose‐derived stem cell; CI, confidence interval; CM, culture medium; CR, clip removal; FA, fractional anisotropy

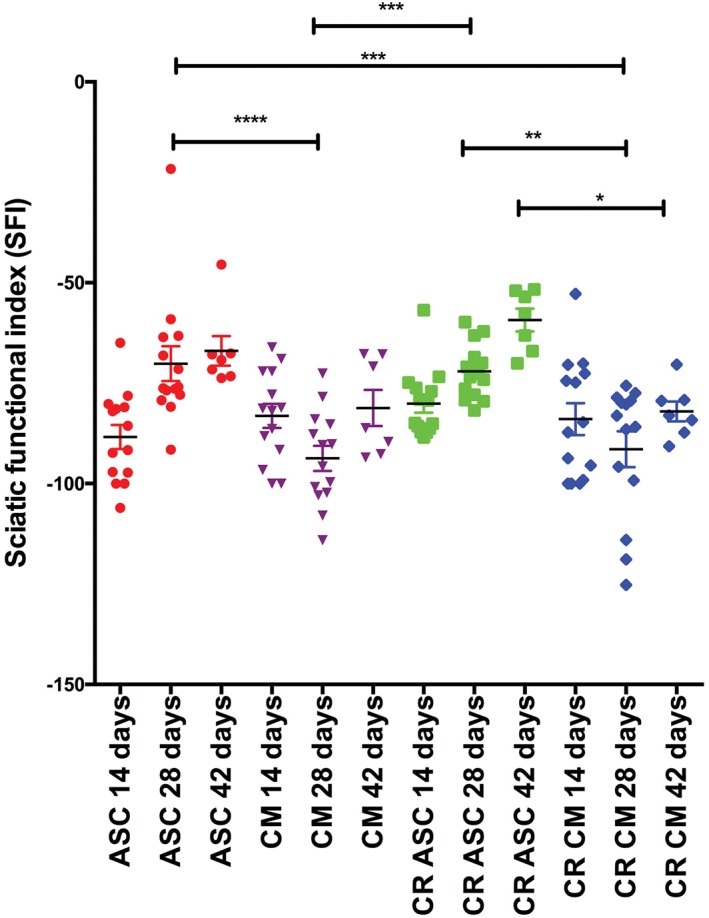

Sciatic Functional Index

Functional analysis showed the best values in the rASC group with CR (−80.1 ± 8.5, −72.1 ± 6.8, and −59.3 ± 7.5 after 14, 28, and 42 days, respectively) and the rASC alone group (−88.4 ± 11.2, −70 ± 16.3, and −67 ± 9.8 after 14, 28, and 42 days, respectively). The lowest results were found in the CM group (−83.2 ± 11.2, −93.7 ± 11.7, and −81.2 ± 11.9 after 14, 28, and 42 days, respectively) and the CM with CR group (−84 ± 15, −91.4 ± 16.7, and −82 ± 6.6 after 14, 28, and 42 days, respectively; Fig. 5). There was a statistically significant difference between the rASC with CR group and the CM with CR group after 42 days, whereas there was no statistically significant difference between the rASC group and the rASC with CR group. Moreover, there was no statistically significant difference between the CM group and the CM with CR group.

Figure 5.

Sciatic function index at 14, 28, and 42 days for each group. Data are expressed as the mean and SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001. ASC, adipose‐derived stem cell; CI, confidence interval; CM, culture medium; CR, clip removal; SFI, sciatic function index. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that rASCs accelerated nerve regeneration after sciatic nerve crush injury with superior functional and morphological results after CR. Statistical adjustments for multiple comparisons, however, showed no significant differences between the CR groups and the corresponding clips on groups for the ratio of MT, fiber diameter, or FD after 28 and 42 days. There was a significant difference in relative gastrocnemius weight in the CR groups compared with the clips on groups after 42 days. There was no statistical significance between the corresponding groups and time points. Overall average FA ratios showed a significant difference only between the CR group with rASC injection and the clip on the group with CM injection, with overall higher values in the CR groups. The SFI showed better values in the CR groups compared with the clip on groups; however, there was no statistically significant difference between any of these groups and time points.

The relative gastrocnemius weight ratio was inferior in the rASC group compared with functional, histomorphological, and MRI analyses in the rASC group, indicating that functional and morphological analyses are not always correlative, as previously reported.10 In most animal studies, immunocytochemistry is the standard method used to measure peripheral neural regeneration.8, 23 Although MRI is a highly attractive imaging modality to monitor the maximum efficacy of cellular therapies,24 only a few investigations have been conducted to date.8

Crush injuries usually occur from an acute traumatic compression of the nerve from a blunt object.25 In chronic compression injuries, a degraded, thinner myelin sheath is seen, as evidenced by an increased g ratio.25 To ameliorate this, SCs proliferate and increase their metabolism to undergo remyelination.25

ASCs produce and release various angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A, VEGF C, and hepatocyte growth factor, which are known to be responsible for neoangiogenesis and the improvement of stem cell microenvironment for grafts, at higher quantities than SCs.26, 27 Moreover, ASCs might differentiate into SCs28 and promote nerve regeneration by providing neurotrophic growth factors.29

Previous studies sought to restore sciatic nerve function after injury by using artificial nerve conduits and scaffolds as well as by delivering cells directly at the lesion site.8, 10, 30, 31 The criticism has been raised that this route of administration induces additional trauma to the injection site as well as that it is difficult to treat multiple or diffuse sites of injury.3 In contrast, in our study, by using an ultrasound guided injection method, the operator was able precisely to assess the correct injection site by being able to visualize swelling of the nerve on the monitor screen during liquid inoculation. Systemic administration of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) capable of reaching the damaged peripheral nerve injury has been suggested.3 It is possible that the mechanism promoting nerve regeneration is not due to differentiation of ASCs but rather suggests a bystander effect, including the production of in situ molecules, which may modulate the local environment with downregulation of inflammation and promotion of axonal regeneration.31

Previous studies have shown that human and autologous stem cell transplantation in a rat sciatic nerve injury model improve peripheral nerve regeneration.8 Kappos et al. 10 recently compared a number of transplantable cells that show promise in peripheral nerve repair. These include rASCs, differentiated rASCs (drASCs), rat SCs, and human ASCs (hASC) from the superficial and deep abdominal layer as well as the human SVF. They found that rats treated with drASCs had a higher mean SFI than those with undifferentiated rASCs and an even higher mean SFI than rats with an autograft.10

Pan et al. 32 applied hyperbaric oxygen to a rat crushed sciatic nerve that was embedded in a fibrin glue rich with amniotic fluid MSCs. The authors reported that the amniotic fluid MSCs/hyperbaric oxygen combined treatment produced the best effect. However, samples of amniotic membrane must be collected immediately after caesarean surgery.33 Therefore, we chose rASCs to accelerate peripheral nerve regeneration because it has been shown that ASCs enhance peripheral nerve regeneration in 86% of experiments.34

Our results are also in line with those of Song et al. 35 These researchers reported that ASCs significantly improved the erectile response to cavernous nerve stimulation and increased endogenous phosphor‐endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation and angiogenic factors compared with controls (nerve crush and phosphate buffered saline).35

For future studies, we will evaluate the effect of CR‐only as a comparison group. Moreover, direct comparison between our groups is limited because we injected rASCs or CM under ultrasonographic control (groups 1 and 2), which requires skills, whereas in the other groups (groups 3 and 4), rASCs or CM were injected to the sciatic nerve by open surgery. In addition, longer term studies are required, including electrodiagnostic tests, and analyses of muscle biopsies are required to determine the ideal strategy for the treatment of sciatic nerve crush injury.

In conclusion, our results indicate that rASCs showed accelerated nerve regeneration in the sciatic nerve crush injury model. Particularly, epineural injection of rASCs with CR showed promising results.

Part of this material was presented at the Global Spine Congress; April 2016; Dubai, United Arab Emirates and at the European Association of Neurosurgical Societies annual meeting; October 2015; Madrid, Spain.

Ethical Publication Statement: We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supplementary figure Microsurgical exploration of the proximal sciatic nerve under microscope (Carl Zeiss®). The black star indicates the clip and black arrow indicates the sciatic nerve.

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1. Grinsell D, Keating CP. Peripheral Nerve Reconstruction after injury: a review of clinical and experimental therapy. Biomed Res Int 2014;698256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Menorca RM, Fussell TS, Elfar JC. Nerve physiology: Mechanisms of injury and recovery. Hand Clin 2013;29(3):317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marconi S, Castiglione G, Turano E, Bissolotti G, Angiari S, Farinazzo A, et al. Human adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells systemically injected promote peripheral nerve regeneration in the mouse model of sciatic crush. Tissue Eng Part A 2012;18(11–12):1264–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ozturk C. Peripheral nerve surgery models sciatic nerve crush injury model In: Siemionow MZ, editor. Plastic and reconstructive surgery: experimental models and research. London: Springer Verlag; 2015. p 513–516. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gold R, Archelos JJ, Hartung HP. Mechanisms of immune regulation in the peripheral nervous system. Brain Pathol 1999;9(2):343–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL. Surgery of the peripheral nerve. New York: Thieme; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wessel LE, Fufa DT, Canham RB, La Bore A, Boyer MI, Calfee RP. Outcomes following peripheral nerve decompression with and without associated double crush syndrome: a case control study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;139(1):119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tremp M, Meyer Zu Schwabedissen M, Kappos EA, Engels PE, Fischmann A, Scherberich A, et al. The regeneration potential after human and autologous stem cell transplantation in a rat sciatic nerve injury model can be monitored by MRI. Cell Transplant 2015;24(2):203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sterodimas A, de Faria J, Nicaretta B, Pitanguy I. Tissue engineering with adipose‐derived stem cells (ADSCs): current and future applications. JPlast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2010;63(11):1886–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kappos EA, Engels PE, Tremp M, Meyer zu Schwabedissen M, di Summa P, Fischmann A, et al. Peripheral nerve repair: multimodal comparison of the long‐term regenerative potential of adipose tissue‐derived cells in a biodegradable conduit. Stem Cells Dev 2015;24(18):2127–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. di Summa PG, Kingham PJ, Raffoul W, Wiberg M, Terenghi G, Kalbermatten DF. Adipose‐derived stem cells enhance peripheral nerve regeneration. JPlast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2010;63(9):1544–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. di Summa PG, Kingham PJ, Campisi CC, Raffoul W, Kalbermatten DF. Collagen (NeuraGen(R)) nerve conduits and stem cells for peripheral nerve gap repair. Neurosci Lett 2014;572:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Engels PE, Tremp M, Kingham PJ, di Summa PG, Largo RD, Schaefer DJ, et al. Harvest site influences the growth properties of adipose derived stem cells. Cytotechnology 2013;65(3):437–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Horan PK, Melnicoff MJ, Jensen BD, Slezak SE. Fluorescent cell labeling for in vivo and in vitro cell tracking. Methods Cell Biol 1990;33:469–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wallace PK, Tario JD Jr, Fisher JL, Wallace SS, Ernstoff MS, Muirhead KA. Tracking antigen‐driven responses by flow cytometry: monitoring proliferation by dye dilution. Cytometry A 2008;73(11):1019–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Poon RY. Flow cytometry and cell sorting protocols In: Diamond RA, DeMaggio S, editors. In living color. New York: Springer Verlag; 2000. p 302–352. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gocmen S, Sirin S, Oysul K, Ulas UH, Oztas E. The effects of low‐dose radiation in the treatment of sciatic nerve injury in rats. Turk Neurosurg 2012;22(2):167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kizilay Z, Erken HA, Cetin NK, Aktas S, Abas BI, Yilmaz A. Boric acid reduces axonal and myelin damage in experimental sciatic nerve injury. Neural Regen Res 2016;11(10):1660–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kalbermatten DF, Kingham PJ, Mahay D, Mantovani C, Pettersson J, Raffoul W, et al. Fibrin matrix for suspension of regenerative cells in an artificial nerve conduit. JPlast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2008;61(6):669–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bozkurt A, Tholl S, Wehner S, Tank J, Cortese M, O'Dey D, et al. Evaluation of functional nerve recovery with visual‐static sciatic index (SSI)—a novel computerized approach for the assessment of the SSI. JNeurosci Methods 2008;170(1):117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haastert K, Lipokatic E, Fischer M, Timmer M, Grothe C. Differentially promoted peripheral nerve regeneration by grafted Schwann cells over‐expressing different FGF‐2 isoforms. Neurobiol Dis 2006;21(1):138–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bain JR, Mackinnon SE, Hunter DA. Functional evaluation of complete sciatic, peroneal, and posterior tibial nerve lesions in the rat. Plast Reconstr Surg 1989;83(1):129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yi C, Dahlin LB. Impaired nerve regeneration and Schwann cell activation after repair with tension. Neuroreport 2010;21(14):958–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cheng LN, Duan XH, Zhong XM, Guo RM, Zhang F, Zhou CP, et al. Transplanted neural stem cells promote nerve regeneration in acute peripheral nerve traction injury: assessment using MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;196(6):1381–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Menorca RMG, Fussell TS, Elfar JC. Peripheral nerve trauma: mechanisms of injury and recovery. Hand Clin 2013;29(3):317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sowa Y, Imura T, Numajiri T, Nishino K, Fushiki S. Adipose‐derived stem cells produce factors enhancing peripheral nerve regeneration: influence of age and anatomic site of origin. Stem Cells Dev 2012;21(11):1852–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takeda K, Sowa Y, Nishino K, Itoh K, Fushiki S. Adipose‐derived stem cells promote proliferation, migration, and tube formation of lymphatic endothelial cells in vitro by secreting lymphangiogenic factors. Ann Plast Surg 2015;74(6):728–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kingham PJ, Kalbermatten DF, Mahay D, Armstrong SJ, Wiberg M, Terenghi G. Adipose‐derived stem cells differentiate into a Schwann cell phenotype and promote neurite outgrowth in vitro . Exp Neurol 2007;207(2):267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kalbermatten DF, Schaakxs D, Kingham PJ, Wiberg M. Neurotrophic activity of human adipose stem cells isolated from deep and superficial layers of abdominal fat. Cell Tissue Res 2011;344(2):251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Deumens R, Bozkurt A, Meek MF, Marcus MA, Joosten EA, Weis J, et al. Repairing injured peripheral nerves: bridging the gap. Prog Neurobiol 2010;92(3):245–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kang JR, Zamorano DP, Gupta R. Limb salvage with major nerve injury: current management and future directions. JAm Acad Orthop Surg 2011;19(Suppl 1):S28–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pan HC, Chin CS, Yang DY, Ho SP, Chen CJ, Hwang SM, et al. Human amniotic fluid mesenchymal stem cells in combination with hyperbaric oxygen augment peripheral nerve regeneration. Neurochem Res 2009;34(7):1304–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dizaji Asl K, Shafaei H, Soleimani Rad J, Nozad HO. Comparison of characteristics of human amniotic membrane and human adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells. World J Plast Surg 2017;6(1):33–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Walocko FM, Khouri RK Jr, Urbanchek MG, Levi B, Cederna PS. The potential roles for adipose tissue in peripheral nerve regeneration. Microsurgery 2016;36(1):81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Song KM, Jin HR, Park JM, Choi MJ, Kwon MH, Kwon KD, et al. Intracavernous delivery of stromal vascular fraction restores erectile function through production of angiogenic factors in a mouse model of cavernous nerve injury. JSex Med 2014;11(8):1962–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supplementary figure Microsurgical exploration of the proximal sciatic nerve under microscope (Carl Zeiss®). The black star indicates the clip and black arrow indicates the sciatic nerve.