Abstract

This observational study evaluates the association of dual prescribing for Veterans Affairs and Medicare Part D benefits with unsafe prescription exposure in a national cohort of older veterans.

Veterans 65 years and older with prescription drug benefits from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) are almost universally eligible for Medicare Part D (hereinafter referred to as Part D). Although dual eligibility may increase access to necessary medications, receiving prescriptions from 2 systems (dual use) may also fragment care and undermine prescribing safety. Previous work showed that dual VA–Part D prescription drug use is a risk factor for potentially unsafe medication (PUM) exposure in veterans with dementia1 and opioid users.1,2 However, whether these risks generalize to the entire Medicare-covered population of older VA users remains unknown. We evaluated the association of dual prescription use through the VA and Part D (vs VA-only use) with the prevalence of PUM exposure in a national cohort of dually eligible older veterans.

Methods

We linked national VA and Part D records of use of health care services and prescriptions in a cohort of 279 940 veterans who were continuously enrolled in VA and Part D and received at least 1 medication through the VA in 2015. We further limited the study to veterans 68 years or older on January 1, 2015.1 We categorized these veterans as dual users (ie, ≥1 medication from the VA and Part D) or VA-only users. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the VA, which waived the need for informed consent.

Dates of administrative health care data use and analysis ranged from January 1, 2012, through December 31, 2015. We examined 4 previously validated PUM measures in 2015: any prescription for a Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set high-risk medication in the elderly (PUM-HEDIS); any exposure to prescriptions with an anticholinergic cognitive burden score of at least 3 (PUM-ACB); any overlapping days of exposure to drug combinations with high risk for severe interactions (PUM-DDI); and a composite measure of any type of PUM exposure.3 We also examined an alternative definition of dual use: the proportion of total prescriptions (VA plus Part D) received from the VA in 2015. Several covariates differed at baseline. We used entropy balancing to achieve covariate balance.4 Unlike propensity weighting, entropy balance weighting directly adjusts the weights to sample means and variances, reducing the effect of model misspecification (Table).

Table. Adjusted Use of PUM Among Older Veterans in 2015 by VA-Only vs Dual VA–Medicare Part D Usea.

| Medication Safety Measure | Dual VA–Part D Use (n = 52 839) | VA-Only Use (n = 227 101) | Differenceb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any PUM | |||

| Exposure, % (95% CI) | 49.7 (49.2-50.0) | 34.9 (34.6-35.2) | +14.8 (14.3-15.3) |

| aOR (95% CI) | 1.84 (1.80-1.88) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Days exposed (95% CI)c | 72.7 (71.6-73.9) | 53.3 (52.5-54.1) | +19.4 (18.1-20.8) |

| PUM-HEDIS | |||

| Exposure, % (95% CI) | 19.3 (18.9-19.6) | 11.6 (11.4-11.8) | +7.7 (7.3-8.1) |

| aOR (95% CI) | 1.82 (1.77-1.88) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Days exposed (95% CI) | 20.2 (19.7-20.8) | 16.0 (15.6-16.4) | +4.2 (3.6-4.9) |

| PUM-ACB | |||

| Exposure, % (95% CI) | 38.6 (38.2-39.0) | 29.0 (28.7-29.3) | +9.6 (9.1-10.0) |

| aOR (95% CI) | 1.53 (1.50-1.57) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Days exposed (95% CI) | 49.6 (48.8-50.4) | 36.1 (35.5-36.7) | +13.5 (12.5-14.5) |

| PUM-DDI | |||

| Exposure, % (95% CI) | 4.4 (4.2-4.6) | 1.4 (1.3-1.5) | +3.0 (2.8-3.1) |

| aOR (95% CI) | 3.25 (3.02-3.48) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Days exposed (95% CI) | 2.9 (2.7-3.1) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | +1.7 (1.5-1.9) |

Abbreviations: ACB, anticholinergic cognitive burden; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; DDI, drug-drug interactions (drug combinations with high risk for severe interactions); HEDIS, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set for high-risk medication in the elderly; NA, not applicable; PUM, potentially unsafe medications; VA, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Includes 279 940 veterans. Covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, US region, county rurality, VA enrollment priority status, Elixhauser comorbidities, number of comorbidities, Veteran Integrated Service Network number, and low-income subsidy status. All covariates were entropy balanced to a standardized difference of P < .001.

All comparisons across Drug Benefit User Groups were statistically significant at the P < .001 level. Bias-corrected bootstrapping was used for assessing the number of days.

Indicates the sum of PUM-HEDIS, PUM-ACB, and PUM-DDI exposure days in 2015. A day when a patient was exposed to all 3 PUMs would count as 3 exposure days.

Results

Among 279 940 Medicare-eligible older veterans receiving a prescription from the VA, 18.9% (95% CI, 18.7%-19.0%) were dual users and 44.3% (95% CI, 37.3%-51.4%) were exposed to at least 1 PUM in 2015. Among dual users, 49.7% (95% CI, 49.2%-50.0%) were exposed to any PUM type, including 38.6% (95% CI, 38.2%-39.0%) to PUM-ACB, 19.3% (95% CI, 18.9%-19.6%) to PUM-HEDIS, and 4.4% (95% CI, 4.2%-4.6%) to PUM-DDI.

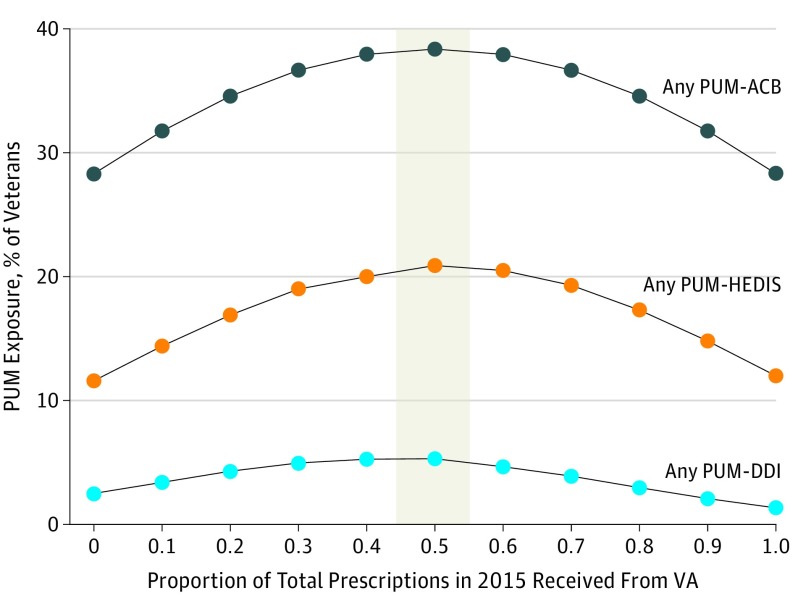

In adjusted results, dual use was associated with increased odds of any PUM exposure (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.84; 95% CI, 1.80-1.88) and an additional 19.4 days of exposure (95% CI, 18.1-20.8 days) (Table). Dual use was also associated with increased odds of PUM-HEDIS (aOR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.77-1.88), PUM-ACB (aOR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.50-1.57), and PUM-DDI (aOR, 3.25; 95% CI, 3.02-3.48). Dual use measured as the proportion of total 2015 prescriptions from the VA revealed that PUM exposure was lowest among VA-only users, and PUM exposure peaked in veterans receiving prescriptions in near-equal proportions (50:50) from the VA and Part D (Figure).

Figure. Probability of Potentially Unsafe Medication (PUM) Exposure.

Exposure to PUM was measured as any prescription for a Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set high-risk medication in the elderly (PUM-HEDIS), prescriptions with an anticholinergic cognitive burden score of at least 3 indicating any daily exposure (PUM-ACB), and any overlapping days of exposure to drug-drug interactions (PUM-DDI). The proportion of total prescriptions from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was measured as total VA prescriptions divided by total VA plus Medicare Part D prescriptions. A proportion of 0.50 indicates 50% from the VA and 50% from Part D (shaded area).

Discussion

Dual use of VA and Part D prescription drug benefits was associated with an almost 2-fold increase in the odds of exposure to any PUM compared with VA-only use and more than 3 times the odds of exposure to severe drug-drug interactions. Despite the limitations of observational studies, our results show that the prescribing safety risks associated with dual VA–Part D use are not limited to high-risk subgroups.1,2 Policies that increase veterans’ access to non-VA health care professionals therefore may unintentionally jeopardize patient safety. Furthermore, it is possible that the safety risks found in this study of veterans may extend to all patients who receive prescriptions across disconnected health care providers or systems. To mitigate these potential risks, policies intended to expand access to non-VA providers must ensure patient information is shared and integrated into routine practice for all patients seeking care across multiple health care systems.5,6

References

- 1.Thorpe JM, Thorpe CT, Gellad WF, et al. Dual health care system use and high-risk prescribing in patients with dementia: a national cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(3):157-163. doi: 10.7326/M16-0551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gellad WF, Thorpe JM, Zhao X, et al. Impact of dual use of Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare Part D drug benefits on potentially unsafe opioid use. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):248-255. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pharmacy Quality Alliance. Medication safety: PQA medication safety measures. Drug-drug interactions (2017 update) (DDI-2017). February 19, 2019. https://www.pqaalliance.org/medication-safety. Updated August 28, 2018. Accessed February 19, 2019.

- 4.Hainmueller J, Xu Y. Ebalance: a Stata package for entropy balancing. J Stat Softw. 2013;54(7):1-18. doi: 10.18637/jss.v054.i07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sisk R. Trump signs $55 billion bill to replace VA Choice Program. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2018/06/06/trump-signs-55-billion-bill-replace-va-choice-program.html. Posted June 6, 2018. Accessed March 2, 2019.

- 6.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . The 2008. Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/downloads/tr2008.pdf. March 25, 2008. Accessed March 15, 2019.