Key Points

Question

Do differences in cataract surgery and total procedural volume exist between US male and female residents during ophthalmology residency training?

Findings

This analysis of the case logs of 1271 ophthalmology residents from 24 US ophthalmology residency programs estimates that female residents performed 7.8 to 22.2 fewer cataract operations and 36.0 to 80.2 fewer total procedures compared with their male counterparts from 2005 to 2017, and the gap widened during this period for total procedural volume.

Meaning

The current state of surgical training in ophthalmology residency programs deserves further study to ensure that male and female residents have equivalent training experiences.

This analysis of case logs from US ophthalmology residency programs assesses differences between male and female ophthalmology residents for cataract surgery and total procedural volume.

Abstract

Importance

Although almost equal numbers of male and female medical students enter into ophthalmology residency programs, whether they have similar surgical experiences during training is unclear.

Objective

To determine differences for cataract surgery and total procedural volume between male and female residents during ophthalmology residency.

Design, Setting, Participants

This retrospective, longitudinal analysis of resident case logs from 24 US ophthalmology residency programs spanned July 2005 to June 2017. A total of 1271 residents were included. Data were analyzed from August 12, 2017, through April 4, 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Variables analyzed included mean volumes of cataract surgery and total procedures, resident gender, and maternity or paternity leave status.

Results

Among the 1271 residents included in the analysis (815 men [64.1%]), being female was associated with performing fewer cataract operations and total procedures. Male residents performed a mean (SD) of 176.7 (66.2) cataract operations, and female residents performed a mean (SD) of 161.7 (56.2) (mean difference, −15.0 [95% CI, −22.2 to −7.8]; P < .001); men performed a mean (SD) of 509.4 (208.6) total procedures and women performed a mean (SD) of 451.3 (158.8) (mean difference, −58.1 [95% CI, −80.2 to −36.0]; P < .001). Eighty-five of 815 male residents (10.4%) and 71 of 456 female residents (15.6%) took parental leave. Male residents who took paternity leave performed a mean of 27.5 (95% CI, 13.3 to 41.6; P < .001) more cataract operations compared with men who did not take leave, but female residents who took maternity leave performed similar numbers of operations as women who did not take leave (mean difference, −2.0 [95% CI, −18.0 to 14.0]; P = .81). From 2005 to 2017, each additional year was associated with a 5.5 (95% CI, 4.4 to 6.7; P < .001) increase in cataract volume and 24.4 (95% CI, 20.9 to 27.8; P < .001) increase in total procedural volume. This increase was not different between genders for cataract procedure volume (β = −1.6 [95% CI, −3.7 to 0.4]; P = .11) but was different for total procedural volume such that the increase in total procedural volume over time for men was greater than that for women (β = −8.0 [95% CI, −14.0 to −2.1]; P = .008).

Conclusions and Relevance

Female residents performed 7.8 to 22.2 fewer cataract operations and 36.0 to 80.2 fewer total procedures compared with their male counterparts from 2005 to 2017, a finding that warrants further exploration to ensure that residents have equivalent surgical training experiences during residency regardless of gender. However, this study included a limited number of programs (24 of 119 [20.2%]). Future research including all ophthalmology residency programs may minimize the selection bias issues present in this study.

Introduction

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires that ophthalmology residency programs enable residents to perform a minimum number of procedural cases and ensure that their trainees have “equivalent educational opportunities.”1(p16) Prior research on cataract surgical training based on data from 1999 to 2002 found that surgical competency improves with increasing case volumes, even beyond the minimum number of required cataract operations for graduation (currently 86).2 The rate of intraoperative complications continues to decrease and operating efficiency continues to increase at case volumes beyond 160. More recent studies3,4 have also found that operating efficiency continues to improve after residents have completed more than 100 cataract cases. These findings suggest the importance of performing a sufficient number of cases during training to graduate as competent ophthalmic surgeons, which may be higher than the current ACGME minimum requirement of 86 cases.

This study examined whether differences exist in cataract surgery and total procedural volumes between male and female residents during ophthalmology training. Disparities between genders have been documented in many areas of ophthalmology, including female underrepresentation in the ranks of academic department chairs, program directors, and faculty.5 Outside the academic setting, a survey of ambulatory surgery centers in Florida found that female surgeons performed fewer than half as many cataract operations per year as male surgeons.6 A systematic review of other surgical specialties has found that at the resident level, no differences in surgical skills exist between men and women,7 but differences between men and women in ophthalmology surgical training have yet to be examined. This study was intended to explore whether such differences exist on the procedural case volume level.

Methods

This retrospective, longitudinal study analyzed case logs for residents graduating from July 2005 through June 2017, which were the years of data available through the ACGME Accreditation Data System website to residency program directors at the time of this study. In August 2017, we contacted program and associate program directors of all 119 US ophthalmology residency programs through an email listserv of the Association of University Professors of Ophthalmology requesting voluntary, anonymous participation by submitting deidentified case log data, including graduation year, resident gender, number of cataract procedures performed as primary surgeon, total number of procedures performed, and parental leave status, for each of their graduating residents during the study period. Each program was also asked to identify its size (small [≤3 residents per year], medium [4-6 residents per year], or large [≥7 residents per year]) and location (Northeast, South, Midwest, or West). Institutional review board approval was obtained via Columbia University Medical Center, which did not require informed consent for the use of deidentified data.

The association among gender, leave, year, and cataract and total procedural volumes was analyzed using univariate and multivariate ordinary least squares regression analysis. Additional analyses included the interactions between gender and leave and between gender and calendar year on case volume. The primary study outcomes were the overall differences in cataract surgery and total procedural volumes between male and female residents. Our secondary outcomes were case volume differences between men and women while controlling for parental leave status and calendar year. Statistical analyses were conducted using StataMP, version 14 (StataCorp LP) with 2-sided significance testing and statistical significance set at <.05.

Results

Twenty-four of 119 total US ophthalmology residency programs (20.2%) submitted data on 1271 residents (815 men [64.1%] and 456 women [35.9%]) who graduated from 2005 to 2017. Comparing programs that submitted data with those that did not (95 of 119 [79.8%]), we found no difference in region (5 of 30 in the Northeast, 5 of 31 in the Midwest, 10 of 41 in the South, and 5 of 17 in the West; P = .62), program director gender (male program directors, 19 of 25 included programs vs 69 of 94 not included; P = .79), program director academic rank (7 of 37 directors of included programs were assistant professors, 8 of 37 were associate professors, and 8 of 25 were full professors; P = .47), or program director appointment duration in years (mean [SD] program director appointment duration, 6.1 [5.4] among included programs vs 5.4 [5.4] among not included programs; P = .49). Programs that submitted data had more residents than programs that did not participate (mean [SD], 4.7 [1.4] vs 4.0 [1.6]; P = .02). Mean (SD) cataract volume was 176.7 (66.2) for male residents and 161.7 (56.2) for female residents. Mean (SD) total procedural volume was 509.4 (208.6) for male residents and 451.3 (158.8) for female residents. One hundred fifty-six residents (85 of 815 men [10.4%] and 71 of 456 women [15.6%]) took parental leave (Table 1).

Table 1. Cataract Surgery and Total Procedural Volume, by Gender.

| Characteristic | All Residents | Male Residents | Female Residents |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of residents | 1271 | 815 | 456 |

| Maternity or paternity leave | 156 | 85 | 71 |

| No. of cataract operations, mean (SD) | 171.3 (63.2) | 176.7 (66.2) | 161.7 (56.2) |

| No. of total surgical procedures, mean (SD) | 488.5 (194.2) | 509.4 (208.6) | 451.3 (158.8) |

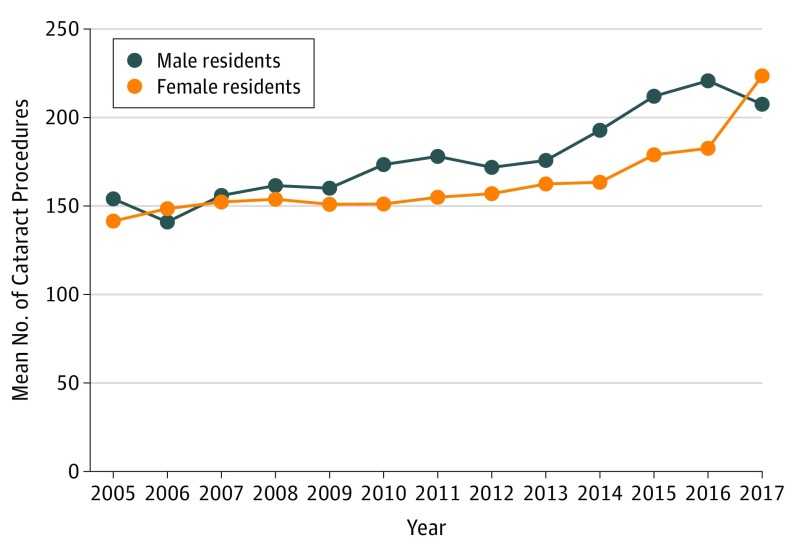

In the univariate regression analysis for cataract surgery volume, being female was associated with performing a mean of 15.0 fewer operations (95% CI, −22.2 to −7.8; P < .001) (Table 2). Gender had a similar association (mean difference, −15.3 [95% CI, −23.5 to −7.2]; P < .001) on cataract surgery volume when parental leave status was included in the regression analysis. Multivariate analyses also showed that being male and taking parental leave was associated with an increase in cataract surgery volume compared with male residents who did not take leave (mean difference, 27.5 [95% CI, 13.3-41.6]; P < .001); however, female residents taking maternity leave performed similar numbers of cataract operations as female residents not taking leave (mean difference, −2.0 [95% CI, −18.0 to 14.0]; P = .81). When calendar year was also included in the regression analysis, a strong association occurred between each additional calendar year and performing more cataract operations (β = 5.5 [95% CI, 4.4-6.7]; P < .001) (Figure 1), although the association of year with the difference between male vs female residents was not significant (β = −1.6 [95% CI, −3.7 to 0.4]; P = .11) (Table 2).

Table 2. Association of Gender, Parental Leave, and Calendar Year With Cataract Surgery Volume and Total Procedural Volume.

| Variable | Regression Coefficient (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cataract Surgery Volume | Total Procedural Volume | |||||

| Analysis 1a | Analysis 2b | Analysis 3c | Analysis 4d | Analysis 5e | Analysis 6f | |

| Gender, mean difference | −15.0 (−22.2 to −7.8) | −15.3 (−23.5 to −7.2) | −6.0 (−20.5 to 8.4) | −58.1 (−80.2 to −36.0) | −64.1 (−89.3 to −38.9) | −18.1 (−60.8 to 24.5) |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | .41 | .001 | <.001 | .40 |

| Leave, mean difference | NA | 27.5 (13.3 to 41.6) | 25.9 (12.4 to 39.5) | NA | 20.0 (−23.7 to 63.8) | 13.3 (−26.7 to 53.2) |

| P value | NA | <.001 | <.001 | NA | .37 | .52 |

| Gender × leave, β coefficient | NA | −29.5 (−50.8 to −8.1) | −29.5 (−50.0 to −9.0) | NA | −25.4 (−91.7 to 41.0) | −25.9 (−86.5 to 34.7) |

| P value | NA | .007 | .005 | NA | .45 | .40 |

| Year, β coefficient | NA | NA | 5.5 (4.4 to 6.7) | NA | NA | 24.4 (20.9 to 27.8) |

| P value | NA | NA | <.001 | NA | NA | <.001 |

| Gender × year, β coefficient | NA | NA | −1.6 (−3.7 to 0.4) | NA | NA | −8.0 (−14.0 to −2.1) |

| P value | NA | NA | .11 | NA | NA | .008 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Regression analysis of cataract surgery volume and gender.

Regression analysis of cataract surgery volume, gender, and leave status.

Regression analysis of cataract surgery volume, gender, leave status, and year.

Regression analysis of total procedural volume and gender.

Regression analysis of total procedural volume, gender, and leave status.

Regression analysis of total procedureal volume, gender, leave status, and year.

Figure 1. Mean Cataract Surgery Volume by Calendar Year and Gender.

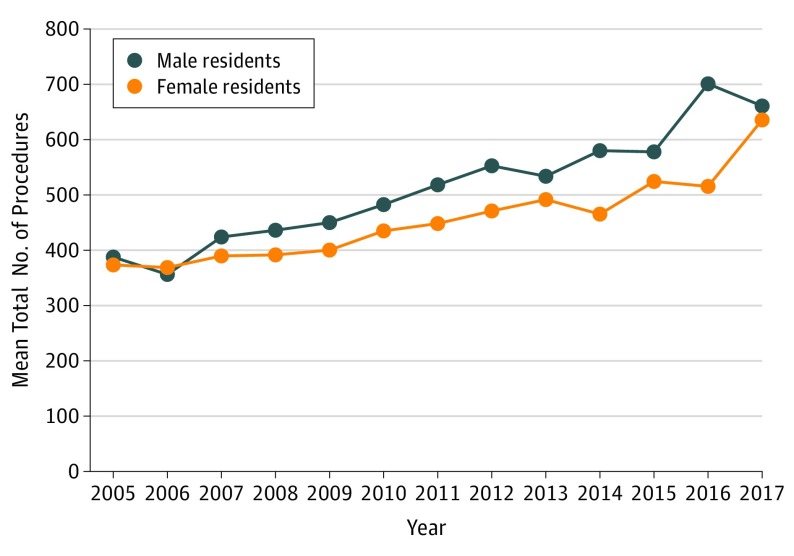

For total procedural volume, gender had a similar association with volume, with women performing fewer total procedures compared with men (mean difference, −58.1 [95% CI, −80.2 to −36.0]; P < .001) in the univariate analysis (Table 2). However, parental leave status was not associated with total procedural volume for male (mean difference, 20.0 [95% CI, −23.7 to 63.8]; P = .37) or female (mean difference, −25.4 [95% CI, −91.7 to 41.0]; P = .45) residents. Similar to cataract surgery volume, calendar year was associated with increasing total procedural volume (β = 24.4 [95% CI, 20.9-27.8]; P < .001), but with each additional calendar year, the differential between genders increased, with female residents performing fewer total procedures compared with male residents (β = −8.0 [95% CI, −14.0 to −2.1]; P = .008) (Figure 2). When analyzing individual programs for cataract surgery, 17 of 24 (70.8%) had male residents performing more operations; for total procedures, 20 of 24 (83.3%) had male residents performing more total procedures.

Figure 2. Mean Total Procedural Volume by Calendar Year and Gender.

Discussion

Our study of 1271 ophthalmology residents from 2005 to 2017 found that graduating female residents performed a mean of 7.8 to 22.2 fewer cataract operations and 36.0 to 80.2 fewer total procedures than male residents. Both male and female residents, however, performed approximately twice the minimum number of cataract operations required by the ACGME. Male residents taking parental leave performed more cataract operations than those not taking parental leave, but female residents taking parental leave performed similar numbers of operations as those who did not take leave. We also found that cataract surgery and total procedural volume increased with time, and a gap increased between male and female resident case volume for total procedures but not cataract surgery. The increase in cataract case volume over time may be due to an expanding and aging population requiring cataract surgery, less stringent indications for patients to undergo cataract surgery, or residency programs’ iterative improvement processes to increase case volume for female and male residents.

Including parental leave in our analysis provided additional insight into the case volume difference between male and female residents. We found that regardless of parental leave status, female residents performed fewer cataract operations compared with male residents. Moreover, analysis of the data by calendar year shows that the difference between male and female resident case volumes appeared to be driven by the middle years in our data set; in fact, for the beginning and end of the study period, male and female residents were performing similar numbers of cases. This finding highlights the importance of examining an extended period, because analyzing a small number of years could yield a completely different conclusion. Factors on several different levels may explain why these differences exist, including but not limited to (1) resident-level factors such as how male vs female residents may explain, consent, and book patients for surgery; (2) attending-level factors such as whether teaching faculty may be more likely to hand off cases to male vs female residents; and (3) patient-level factors such as how patients may perceive male and female resident physicians explaining the same surgical procedure in the same manner. In addition, institutional-level factors affect a residency program’s case volume, including time spent in attending- vs resident-driven clinics, operating room availability for residents, attending staffing availability, ease of booking resident surgical cases, and residency program size. How these institutional-level factors may differentially affect male vs female residents needs additional attention.

Further exploring resident characteristics may also help explain the unexpected finding that male residents taking parental leave perform more cataract operations than their male counterparts who do not: differences in age, personality, financial support, family support, and other areas may exist between these 2 groups. Although our data set does not contain this information, age would be a particularly important factor to consider. If male residents taking parental leave are older than male residents who do not take leave, this difference may favor the former if attendings are more willing to pass on cases to older residents and patients are more willing to undergo surgery with older residents. Beyond the differences in baseline characteristics between these 2 groups of male residents, on the residency level, programs may be making an extra effort to help male residents taking parental leave find surgical cases to make up for the leave time. For female residents, residency programs may also be making the effort to assist those who take parental leave, because case volumes for female residents taking parental leave are similar to those for female residents not taking parental leave. One concerning trend that deserves special mention is the growing gap in total procedural volume between male and female residents as time progresses. Although we are encouraged that overall case volume increased from 2005 to 2017, it is unclear why the increase asymmetrically affects male and female residents. Our study also found that for total procedural volume, parental leave did not have an effect on case volume for male or female residents. One possible explanation may be that if residents are more likely to take parental leave in their third year, taking leave would have less of an effect on procedural volume during the first and second years of residency when many laser and other procedures are performed.

Based on our findings, we recommend that program directors look at the case volumes of male and female residents within their own programs. If differences exist, they should examine how program policies may differ between men and women starting with the following issues: (1) how the program helps residents make up for case volume when taking parental leave; (2) how rotation schedules can be adjusted based on timing of parental leave to minimize disruption to resident education; and (3) how and when attendings pass on surgical cases to residents. Future streams of research may also determine whether the difference in male and female case volumes is clinically significant and what is an acceptable difference between residents regardless of gender. Previous research suggests that clinically meaningful improvements between the 160th and 180th cases performed may exist in terms of decreasing the rate of vitreous loss and improving operating efficiency.2 If these findings hold true, then reducing the case volume difference between men and women is important to ensure that male and female residents are trained to be equally competent ophthalmic surgeons.

Limitations

First, submission of anonymous case log data was solicited via email and performed voluntarily by 24 participating programs of a total of 119. The resident case volume for the participating programs may have different trends than the programs that did not submit their data, resulting in selection bias that cannot be fully addressed without including data for all ophthalmology residency training programs. Programs participating in this study may be more interested in parity of male and female resident case volumes and consequently had less of a gender difference than programs not participating in this study, thus resulting in an underestimate of the actual difference between male and female resident case volumes. On the other hand, program directors who are more unsure about how their case volumes differ by gender may be more likely to participate, and these types of programs may have a greater gender difference than the mean. Second, program directors submitted case log data based on the self-reporting of their past residents, but we were unable to verify the accuracy of the self-reported numbers. In addition, no oversight of the entry of case log information by residents for ACGME reporting requirements was available. Late entry results in the possibility of recall bias; one potential concern is that residents with fewer case volumes may be more likely to record all of their cases so as to meet ACGME requirements. If male and female residents are performing differing numbers of cases, recall bias may affect these 2 groups of residents differently.

Third, we did not have data on the duration of parental leave taken, which may have an effect on an individual resident’s case volume; this duration may be different for male vs female residents and a possible explanation for why parental leave had a differential effect on case volume for male vs female residents. In addition, some residents taking extended parental leaves may have had different graduation dates from residency training, which could affect their case volume. Fourth, we did not account for subspecialty choice for each graduating resident, which may be an additional explanatory factor for the difference in case volume between male and female residents if one gender is more likely to enter certain ophthalmology subspecialties; for example, for residents pursuing fellowship training in neuro-ophthalmology or retina, it may be less of a priority for those residents to perform greater numbers of cataract operations compared with residents going into comprehensive ophthalmology, cornea, or glaucoma. Fifth, different residency programs may have varying definitions of what counts as a primary surgical case. In addition, male vs female residents may have varying thresholds for what they might count as a primary case, which may artificially increase or decrease the case volume gap between the sexes. This effect is unknown and could not be accounted for in our study.

Conclusions

Female residents in the 24 programs evaluated from 2005 to 2017 performed fewer cataract operations and total procedures during training compared with male residents irrespective of parental leave status, and the gap between male and female residents for total procedural case volume grew from 2005 to 2017. Given the limited number of programs providing data based on voluntary participation in this study in addition to our inability to verify the accuracy of submitted case log data, these conclusions should represent preliminary findings that serve as the basis for replication and validation in larger cohorts in future investigations. Educators must be aware of these differences to address the apparent disparities and their root causes.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Ophthalmology. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/240_ophthalmology_2017-07-01.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed September 1, 2017.

- 2.Randleman JB, Wolfe JD, Woodward M, Lynn MJ, Cherwek DH, Srivastava SK. The resident surgeon phacoemulsification learning curve. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(9):1215-1219. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.9.1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taravella MJ, Davidson R, Erlanger M, Guiton G, Gregory D. Characterizing the learning curve in phacoemulsification. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(6):1069-1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.12.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiggins MN, Warner DB. Resident physician operative times during cataract surgery. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2010;41(5):518-522. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20100726-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah DN, Volpe NJ, Abbuhl SB, Pietrobon R, Shah A. Gender characteristics among academic ophthalmology leadership, faculty, and residents: results from a cross-sectional survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17(1):1-6. doi: 10.3109/09286580903324892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.French DD, Margo CE, Campbell RR, Greenberg PB. Volume of cataract surgery and surgeon gender: the Florida ambulatory surgery center experience 2005 through 2012. J Med Pract Manage. 2016;31(5):297-302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali A, Subhi Y, Ringsted C, Konge L. Gender differences in the acquisition of surgical skills: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(11):3065-3073. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4092-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.