Abstract

Current efforts to prevent progression from islet autoimmunity to type 1 diabetes largely focus on immunomodulatory approaches. However, emerging data suggest that the development of diabetes in islet autoantibody–positive individuals may also involve factors such as obesity and genetic variants associated with type 2 diabetes, and the influence of these factors increases with age at diagnosis. Although these factors have been linked with metabolic outcomes, particularly through their impact on β-cell function and insulin sensitivity, growing evidence suggests that they might also interact with the immune system to amplify the autoimmune response. The presence of factors shared by both forms of diabetes contributes to disease heterogeneity and thus has important implications. Characteristics that are typically considered to be nonimmune should be incorporated into predictive algorithms that seek to identify at-risk individuals and into the designs of trials for disease prevention. The heterogeneity of diabetes also poses a challenge in diagnostic classification. Finally, after clinically diagnosing type 1 diabetes, addressing nonimmune elements may help to prevent further deterioration of β-cell function and thus improve clinical outcomes. This Perspectives in Care article highlights the role of type 2 diabetes–associated genetic factors (e.g., gene variants at transcription factor 7-like 2 [TCF7L2]) and obesity (via insulin resistance, inflammation, β-cell stress, or all three) in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes and their impacts on age at diagnosis. Recognizing that type 1 diabetes might result from the sum of effects from islet autoimmunity and type 2 diabetes–associated factors, their interactions, or both affects disease prediction, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes is the most common form of pediatric diabetes, and if the current increase in incidence continues in the U.S., the number of cases is expected to triple to almost 600,000 U.S. children by 2050 (1). Interestingly, the number of new cases of type 1 diabetes is likely as large as that among adults, although overall, type 2 diabetes is diagnosed more frequently in older individuals (2).

It is possible to predict the development of type 1 diabetes before clinical diagnosis on the basis of genetic (HLA and non-HLA genes), immunologic (islet autoantibodies), and metabolic (e.g., low C-peptide, abnormal glucose) factors (reviewed in ref. 3). Realizing that the identifiable appearance of multiple islet autoantibodies and the occurrence of metabolic abnormalities precede clinical type 1 diabetes underscores an opportunity for preventing disease. Several therapeutic agents have shown promise because of their ability to arrest the decline in β-cell function in those who have been recently diagnosed, thereby providing strong support for the concept of intervening in at-risk individuals before diagnosis in order to halt the progression to clinical disease (4). Some trials, however, have failed to show efficacy in prevention for the overall cohort but still suggest the possibility of effect in specific subsets, such as younger participants (reviewed in ref. 5). This observation points toward the heterogeneity of type 1 diabetes as a barrier against effective and safe approaches to disease prevention. Dissecting the pathogenic mechanisms that underlie various type 1 diabetes phenotypes will probably lead to improvements in trial results. In this article, we refer to type 1 diabetes as a disorder “due to autoimmune β-cell destruction, usually leading to absolute insulin deficiency,” and to type 2 diabetes as “due to a progressive loss of β-cell insulin secretion frequently on the background of insulin resistance,” as defined by the American Diabetes Association (6).

Growing evidence indicates that genetic and metabolic factors known to contribute to type 2 diabetes might also play a role in the pathogenesis and development of diabetes in individuals who have markers of islet autoimmunity. This Perspectives in Care article reviews recent data on the role of type 2 diabetes–associated factors, including gene variants, obesity, and their interactions with age, that have recently been demonstrated to influence progression to diabetes in individuals with circulating islet autoantibodies. These factors might work through nonimmune mechanisms (e.g., insulin resistance or β-cell function defects) but could also interact with the immune system to accelerate the autoimmune destruction of β-cells. Recognizing the role of factors typically associated with type 2 diabetes in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes has important implications. Specifically, nonautoimmune causes may need to be considered in predictive algorithms that aim to identify at-risk individuals, when designing strategies to prevent the disease, and after clinical diagnosis, when establishing treatments that are tailored to the pathogenic mechanisms at play in a given individual.

Type 2 Diabetes–Associated Genes

Genetics are considered to account for about 50% of the risk of type 1 diabetes. The HLA region is the main contributor to the heritability of type 1 diabetes, and various genotypes within the highly polymorphic region confer significant risk for or protection against disease (reviewed in ref. 7). In addition, over 50 non-HLA genetic factors have been reported in association with type 1 diabetes (reviewed in ref. 7). The influence of type 1 diabetes–associated genes, however, varies among subsets of individuals; for example, this influence weakens as the age at diagnosis increases (8). Conversely, genetic variants in type 2 diabetes–associated regions are found more often in certain subsets of individuals with autoimmune type 1 diabetes; these variants are linked to distinctive phenotypes and possibly contribute to pathogenesis.

TCF7L2

TCF7L2 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the genetic factors most strongly associated with type 2 diabetes (9). In addition, they increase the risk for cystic fibrosis–related diabetes (10). TCF7L2 gene variants are linked with impaired insulin secretion, defects in incretin- and glucose-induced glucagon suppression, abnormal insulin processing, increased hepatic glucose release during fasting, and abnormal β-cell development (reviewed in ref. 11), as well as insulin resistance (12).

Evidence is accumulating that SNPs in this region may also influence the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes in certain subsets of individuals, particularly those with fewer classic factors linked to type 1 diabetes, such as a lack of multiple islet autoantibodies or type 1 diabetes–susceptible HLA genotypes. Among children with type 1 diabetes, those who expressed a single islet autoantibody at diagnosis were more likely than those with multiple autoantibodies to carry a type 2 diabetes–associated TCF7L2 gene variant (13). This finding is consistent with data from children and adults with type 1 diabetes participating in the TrialNet Pathway to Prevention study, which follows autoantibody-positive relatives at risk for progression to type 1 diabetes, or the TrialNet New Onset clinical trials (14). The probability is low that some of these single islet autoantibody cases are false positives because, in the TrialNet Pathway to Prevention study, single autoantibody positivity must be confirmed from a separate blood sample; in the TrialNet New Onset clinical trials, islet autoantibodies are measured after a clinical diagnosis of type 1 diabetes has been made. Both strategies reduce the probability of false positivity. The individuals in the TrialNet studies who developed type 1 diabetes despite having only mild islet autoimmunity, as reflected by single autoantibody positivity, had a genetic factor known to cause type 2 diabetes. Of note, in the TrialNet analysis, the relationship between single autoantibody positivity and type 2 diabetes–associated TCF7L2 gene variants was limited to participants older than 12 years of age (14), possibly indicating that TCF7L2-associated mechanisms are relatively slow to cause diabetes or, alternatively, that they need to interact with sex hormones (e.g., via insulin resistance, defects in glucagon suppression, or other pathways). In a T1D Exchange BioBank study, participants with autoimmune type 1 diabetes who carried a type 2 diabetes–associated TCF7L2 SNP were less likely to have the HLA genotype DRB1*03:01/DR4 (DRB1*04:01, *04:05, or *04:02), which indicates high risk for type 1 diabetes, than were participants without the TCF7L2 variant (0 of 13 vs. 27 of 92 participants; P = 0.023) (15). This inverse association between type 1 diabetes– and type 2 diabetes–related genes also supports the concept that individuals who have type 1 diabetes in the absence of typical high-risk influences carry type 2 diabetes–associated factors.

Individuals with type 1 diabetes who carry the type 2 diabetes–associated TCF7L2 gene variant may display a distinct phenotype. We found that, in addition to being more likely to have a single islet autoantibody, TrialNet participants who have autoimmune type 1 diabetes and carry the type 2 diabetes–associated TCF7L2 SNP had at diagnosis a smaller area under the curve for glucose and a larger area under the curve for C-peptide (14). These milder metabolic characteristics are closer to those usually observed in type 2 diabetes, which might suggest that diabetes in these individuals could be largely the result of type 2 diabetes–associated mechanisms. Because most individuals with single autoantibody positivity do not progress to type 1 diabetes, the presence of the type 2 diabetes–associated TCF7L2 variant could be what ultimately caused progression to clinical disease. Therefore, diabetes in these cases could have resulted from the addition of TCF7L2-associated mechanisms to some degree of β-cell loss caused by mild islet autoimmunity (Fig. 1). On the other hand, this additive model may not apply to individuals with aggressive autoimmune destruction of β-cells that would render negligible the milder, slowly progressive effect of TCF7L2 mechanisms.

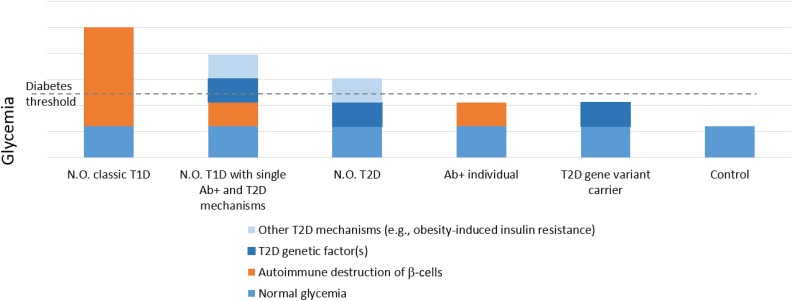

Figure 1.

Postulated model for the relative contributions of autoimmune and nonimmune pathogenic mechanisms to the glucose levels observed in various settings. Individuals with classic type 1 diabetes (T1D) usually present with extreme hyperglycemia and autoimmune destruction of β-cells as the main pathogenic mechanisms. Individuals with only mild autoimmunity (e.g., positive for a single autoantibody) may exceed the glycemic threshold for diabetes in the presence of additional diabetogenic factors, such as type 2 diabetes (T2D)–associated TCF7L2 gene variants, other T2D-associated mechanisms (e.g., insulin resistance), or both. Individuals with classic T2D may exceed the glycemic threshold for diabetes because of the combination of genetic (e.g., TCF7L2 gene) and other (e.g., insulin resistance) mechanisms. Individuals with islet autoantibody positivity (Ab+) in the early stages do not exceed the diabetes threshold, but their glucose may be higher than that in control individuals. Similarly, individuals who carry the T2D-associated TCF7L2 genetic variant have higher glucose than controls but may not exceed the glycemic threshold for diabetes if they lack other risk factors. N.O., new onset.

Furthermore, TCF7L2 gene variants could influence the progression of islet autoimmunity. In a recent analysis of TrialNet Pathway to Prevention participants, obese and overweight individuals with a single confirmed insulin autoantibody (microinsulin autoantibody assay) or IA-2 autoantibody were more likely to progress to multiple autoantibody positivity in the presence of a type 2 diabetes–associated TCF7L2 risk allele, whereas this effect was not present in lean participants (16). The effect of the interaction between the TCF7L2 SNPs and BMI on type 2 diabetes risk has been reported previously (17). Although the mechanisms underlying this interaction are unknown, they could involve acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 5, a protein that influences fatty acid metabolism and whose expression is regulated by TCF7L2 (12). In addition, elevated BMI increased the progression of islet autoimmunity (i.e., from single confirmed to multiple autoantibody positivity) in a specific subset of individuals—namely, children older than 9 years of age without the high-risk type 1 diabetes–associated HLA haplotypes (C.T. Ferrara, S.M. Geyer, C.E.-M., I.M. Libman, D.J. Becker, S.E. Gitelman, M.J.R., unpublished data). Hence, TCF7L2 gene variants could exacerbate islet autoimmunity through obesity-induced pathways (detailed in the next section).

In contrast to insulin autoantibody and IA-2 autoantibody as single confirmed autoantibodies, the TCF7L2 risk allele was associated with a lower risk of progression to multiple autoantibody positivity when GAD65 was the first autoantibody (GAD autoantibody [GADA]) (16). Because TCF7L2 is involved in β-cell differentiation, abnormalities in gene expression could provide protection against antigen spreading by hiding β-cells from the autoimmune attack. The opposite influence of TCF7L2, based on autoantibody specificity, in individuals with single autoantibody positivity is not surprising; previous reports have described two distinct forms of type 1 diabetes: one with insulin autoantibody as the first autoantibody in young children and an association with HLA-DR4, and the other with GADA as the first positive autoantibody in older subjects and usual association with HLA-DR3 (18).

Taken together, these data indicate that individuals with milder islet autoimmunity, as reflected by single autoantibody positivity, may develop diabetes in the presence of an additional diabetogenic factor such as a type 2 diabetes–associated TCF7L2 gene variant; thus, these people have at onset metabolic characteristics that are closer to those of type 2 diabetes (e.g., lower glucose, higher C-peptide). In addition, TCF7L2 SNPs could influence the progression of islet autoimmunity, with different effects based on autoantibody specificity and age. However, further studies are necessary to fully define the mechanisms involved and establish whether they act independently or through interaction.

Gli-Similar 3 Protein

Mutations in Gli-similar 3 protein (GLIS3) cause a syndrome comprising neonatal diabetes, congenital hypothyroidism, glaucoma, hepatic fibrosis, and polycystic kidney disease (reviewed in ref. 19). GLIS3 gene variants are also associated with both type 2 and type 1 diabetes (19). Studies have demonstrated that GLIS3 influences progression to type 1 diabetes in children who are genetically at risk (20), autoantibody-positive children (21), and adults (22). GLIS3 is a member of the Krüppel-like zinc finger protein subfamily, which is predominantly expressed in the pancreas, thyroid, and kidney. GLIS3 is a transcription factor, a key regulator of pancreatic β-cell development and health, and an important regulator of insulin gene expression (19). As such, GLIS3 contributes to the control of fetal islet differentiation via transactivation of neurogenin 3, which, when impaired, leads to neonatal diabetes. GLIS3 is also required for β-cell survival and proliferation in response to insulin resistance, which could be the mechanism responsible for predisposition toward type 2 diabetes. Interestingly, GLIS3 gene variants increased β-cell apoptosis and cytokine-induced β-cell death via alternative splicing of the proapoptotic protein Bim and exacerbated formation of the proapoptotic variant BimS in cultures of INS-1E cells, FACS-purified rat β-cells, and human islets. Therefore, this region seems to be involved in both nonimmune (e.g., insulin resistance) and autoimmune (e.g., proinflammatory cytokines) pathways that lead to β-cell loss and diabetes. Furthermore, by increasing β-cell susceptibility to apoptosis, variants in this region might provide a shared path through which both nonimmune and immune factors can harm fragile β-cells (23). However, it is not known whether a specific type 1 diabetes phenotype is associated with this variant.

Obesity

The increasing prevalence of obesity has been proposed as one factor contributing to the rising incidence of type 1 diabetes. The accelerator or overload hypothesis postulates a relationship between overnutrition and insulin resistance in the development of type 1 diabetes (24). A study of 9,248 German and Austrian children demonstrated higher SD score (SDS) weight and SDS BMI at onset in children who were younger at onset of type 1 diabetes (25). The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth (SEARCH) study also observed that, among youth with low C-peptide, SDS BMI and age were inversely related at the onset of type 1 diabetes (26), despite the weight loss that usually precedes diagnosis. The Australian BabyDiab study, a prospective birth study of patients’ first-degree relatives, followed infants for over 5 years and found that weight and BMI predicted islet autoimmunity at 2 years of age and over time (27). Data from both pediatric and adult participants in the Diabetes Prevention Trial–Type 1 (DPT-1) showed that HOMA of insulin resistance was significantly associated with progression to diabetes (28). Furthermore, a DPT-1 Risk Score, which includes BMI, predicts progression to diabetes (29). Data from TrialNet indicate that higher SDS BMI or BMI percentile in obese adolescents (ages 13–20 years), and higher HOMA of insulin resistance in adults (though not in the overall group), moderately increased the risk of type 1 diabetes (30). The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study, an international trial following from birth children at increased risk for type 1 diabetes, found that development of islet autoimmunity was related to weight measures at 12 months but not at 24 or 36 months; however, no association was found between weight or height and progression to type 1 diabetes diagnosis (31).

Other studies did not find evidence for the involvement of obesity in type 1 diabetes pathogenesis (reviewed in ref. 32), which could be related, at least in part, to differences in study populations, the timing of BMI assessments in relation to type 1 diabetes diagnosis, and study design (e.g., prospective studies are generally better suited to studying causality than are cross-sectional approaches).

To overcome the limitation of using BMI measured at a single time point, we recently analyzed the effect of cumulative excess BMI, which incorporates longitudinal measures of age- and sex-adjusted BMI. We studied 1,117 pediatric participants in the observational arm of the TrialNet Pathway to Prevention study and, after adjusting for age, sex, and number of autoantibodies, we found that children with cumulative BMI in the overweight or obese range had a 63% greater risk of type 1 diabetes (33). Of note, the threshold for the detrimental influence of BMI on type 1 diabetes risk was lower in girls (particularly if younger than 12) than in boys (particularly if older than 12). A potential explanation for this differential effect by age and sex is that the increase in BMI in growing boys largely reflects muscle mass buildup driven by testosterone. On the other hand, at the same BMI, girls might have a higher percentage of body fat. Similarly, among adult participants in the observational TrialNet Pathway to Prevention study, the risk of progression to type 1 diabetes was increased in men 35 years or older and women younger than 35 years who had a sustained BMI above the threshold for obesity (34), which could be related to the ratio of testosterone to estrogen shifting in opposite directions in men and women as they age. Of note, other factors (e.g., puberty, pregnancy, aging) might also induce insulin resistance, which could, in the same way, accelerate the progression to type 1 diabetes in at-risk individuals.

A recent study using Mendelian randomization found evidence for causal associations between genetic variants linked to early childhood obesity and type 1 diabetes (35). That meta-analysis studied 5,913 type 1 diabetes cases and 8,828 reference samples, analyzed 23 SNPs associated with childhood obesity, and found a 32% increased risk of type 1 diabetes (odds ratio 1.32 [95% CI 1.06–1.64]) associated with a 1-SD increase in BMI. Although the precise mechanisms are still unknown, some potential explanations have been proposed for the relationship between obesity and type 1 diabetes. At a purely metabolic level, obesity is thought to accelerate the clinical onset of type 1 diabetes by increasing insulin resistance, and thus insulin needs, in individuals whose ability to secrete insulin has already been compromised by autoimmune-mediated β-cell dysfunction and loss. This could explain why an association between higher BMI and younger age at onset was found only in persons with compromised β-cell function, as reflected by low C-peptide levels, in some of the studies (26). Because an obesity-induced proinflammatory adipokine profile has been demonstrated to lead to β-cell death in type 2 diabetes (reviewed in ref. 36), a more speculative explanation for the influence of elevated BMI on type 1 diabetes is that obesity-induced inflammation could contribute to β-cell death in type 1 diabetes (similar to type 2 diabetes).

Finally, chronically increased β-cell secretory demand, occurring as a result of overnutrition, obesity, and insulin resistance, may lead to the activation of intrinsic β-cell stress pathways that could either trigger autoimmunity through the formation of neoantigens or act independently to accelerate autoimmune-mediated β-cell death. Among the most studied of these pathways is β-cell endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, which is activated when an imbalance exists between the need to produce insulin and the ability of the ER to process and properly fold insulin molecules. Expression of ER stress markers is upregulated in pancreatic sections from human organ donors with type 1 diabetes (37). Furthermore, in vitro studies have shown that human β-cell responses to type I interferon cytokines (specifically IFN-α) include activation of β-cell ER stress signaling and a feed-forward cycle of inflammation (including chemokine release), along with massive HLA class I overexpression, which serves as a homing signal for self-reactive T cells (38). Along these lines, the development of β-cell ER stress and other immune-induced stress pathways has been linked with the development of highly immunogenic neoantigens that are produced through a variety of processes (39). Furthermore, lipid-induced β-cell fragility (i.e., susceptibility to apoptosis) might contribute to the interaction between obesity and islet autoimmunity (23). In summary, several pathways have been proposed that could plausibly explain the effects of obesity on the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes: by altering the balance between insulin secretion and insulin requirements, by contributing to β-cell death, by augmenting the autoimmune attack on β-cells, or all three.

These findings raise the important possibility that agents targeting either insulin resistance or β-cell health could improve outcomes in type 1 diabetes. To date, however, few studies have addressed this question. Although some studies have tested the effects of metformin, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, sodium–glucose cotransporter (SGLT) 2 inhibitors, dual SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibitors, pramlintide, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, thiazolidinediones, and α-glucosidase inhibitors on glucose control, insulin dose, body weight, and other clinically relevant outcomes, noninsulin therapies have not been well developed for use in type 1 diabetes (40).

Age

While younger age at seroconversion accelerates the progression of islet autoimmunity and the development of type 1 diabetes, older age is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes. The factors responsible for the latter association are unclear and probably complex. Among the multiple mechanisms implicated are age-related insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction (reviewed in ref. 41), ER stress secondary to chronic activation of mTORC1 (42), and declining NAD+ levels (43).

In autoimmune diabetes, the rate of progression to insulin insufficiency decreases with age, and latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) is at the extreme of the spectrum. LADA (reviewed in ref. 44) is usually defined as autoimmune diabetes diagnosed after age 30 that does not require insulin treatment in order to maintain glucose control and avoid ketosis for at least the first 6 months. Compared with children with type 1 diabetes, adults with LADA have higher C-peptide at diagnosis, a lower mean number of islet autoantibodies, and a weaker association with HLA. Factors linked with type 2 diabetes are more common in LADA—namely, overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes–related genetic variants—than in childhood-onset type 1 diabetes (44). It should be noted that racial differences exist in the clinical, immunologic, and genetic factors associated with LADA (reviewed in ref. 45). By using type 1 and type 2 diabetes genetic risk scores, a recent study found that although LADA is genetically closer to type 1 than to type 2 diabetes, it has an important type 2 diabetes genetic load (46); however, controversy exists as to the role of specific contributing genes. A lower GADA titer has been linked to a metabolic phenotype closer to that of type 2 diabetes (47). Therefore, LADA represents an example of diabetes that results from the additive effect (and possibly interaction) of autoimmune β-cell loss and type 2 diabetes mechanisms, with clinical implications. Sulfonylureas may hasten insulin dependence in individuals with LADA, but newer noninsulin drugs such as glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors have demonstrated positive effects on glucose control and possibly on β-cell function (reviewed in ref. 48).

Age at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes was negatively correlated with the type 1 diabetes genetic risk score, which combines odds ratios for 30 SNPs that tag HLA (e.g., HLA DQ2/DQ8, indicating the highest risk, and the protective DRB1*15:01, among others) and non-HLA regions (8). Similarly, the type 1 diabetes genetic risk score was a strong predictor of progression from single confirmed to multiple autoantibody positivity in individuals younger than age 35 but not in older participants (49). It is possible that a subset of individuals who develop autoimmune diabetes at an older age have a lighter type 1 diabetes genetic load and thus a less aggressive autoimmune attack on β-cells, with primarily nonautoimmune factors (e.g., obesity, type 2 diabetes–linked genetic factors) acting as more important contributors to their disease. As seen in type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance and β-cell function defects may require more time to cause disease than islet autoimmunity. Furthermore, the association between type 2 diabetes–associated TCF7L2 variants and single autoantibody positivity at the onset of type 1 diabetes was restricted to individuals 12 years of age and older (n = 504), whereas it was not found in younger children, although the sample size was smaller (n = 306) (16). On the other hand, in individuals with aggressive islet autoimmunity and thus rapid and profound insulin deficiency, severe autoimmune β-cell loss would substantially reduce the relative contribution of potential nonautoimmune factors such as insulin resistance or β-cell function defects.

In summary, we postulate that in individuals with mild, slowly progressive islet autoimmunity, nonimmune diabetogenic factors may promote progression to clinical diabetes (Fig. 2). Although the aggressiveness of islet autoimmunity is inversely correlated with age (reviewed in ref. 5), the importance of nonimmune mechanisms increases with age (Fig. 3). The finding that immunomodulatory therapies to prevent progression of type 1 diabetes are less effective in adults than in children further supports this hypothesis (5).

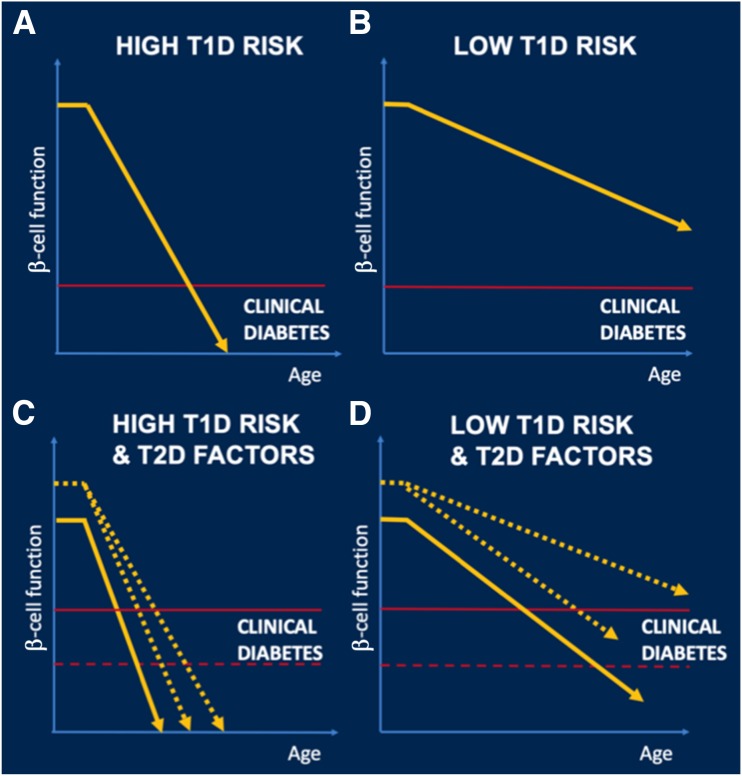

Figure 2.

Hypothesis of the role of type 2 diabetes (T2D) factors in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes (T1D). Compared with individuals with high-risk factors for T1D (e.g., multiple positive islet autoantibodies) (A), those with low-risk factors (e.g., single islet autoantibody positivity) (B) have low rate of progression to T1D and most of them never develop diabetes. However, the presence of T2D factors can accelerate progression to diabetes in at least three ways (C and D). Firstly, the balance between insulin needs and insulin secretion that maintains euglycemia (horizontal red line) could be altered by insulin resistance induced by obesity and/or T2D-associated TCF7L2 genetic variants. Secondly, T2D-associated TCF7L2 SNPs and obesity can accelerate the rate of progression to T1D (yellow slope) by increasing the risk of conversion from single to multiple autoantibody positivity. Finally, β-cell function before the start of the autoimmune destruction of β-cells could be decreased because of T2D-associated genetic variants (start of the horizontal segment in yellow line on the y-axis). Although T2D factors could be present in individuals with high T1D risk factors (C) and accelerate their onset of clinical disease, the relative effect of T2D factors in these individuals is small because of the overwhelming aggressivity of their β-cell destruction. In comparison, in individuals with low risk T1D factors (D), T2D factors are decisive in their progression to diabetes.

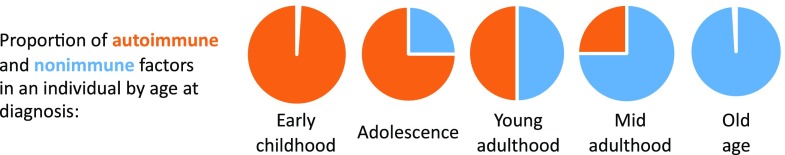

Figure 3.

Postulated model for the relative proportions of autoimmune and nonimmune factors, by age at presentation, in individuals with autoimmune diabetes. Aggressive autoimmune destruction of β-cells is the main cause of type 1 diabetes in young children. Older youth may have milder islet autoimmunity, but the addition of (or interaction with) nonimmune factors (e.g., puberty-induced insulin resistance) can cause progression to diabetes. As age advances, the relative proportion of autoimmune factors is smaller (because islet autoimmunity tends to be milder), and thus nonimmune factors (e.g., type 2 diabetes–associated TCF7L2 gene variants, obesity-induced mechanisms) contribute to diabetes in individuals who develop clinical disease. The autoimmune component is minimal in older individuals, and most of their diabetes has a nonimmune origin.

Implications of the Role of Type 2 Diabetes–Associated Factors in Type 1 Diabetes Pathogenesis

The DPT-1 Risk Score, which is a predictor of type 1 diabetes in autoantibody-positive individuals (29), incorporates BMI. Similarly, type 2 diabetes–related genetic loci, such as TCF7L2 and GLIS3 SNPs, could be incorporated into models in order to predict progression to clinical diabetes in specific subsets of individuals who are at risk for type 1 diabetes (e.g., those positive for a single autoantibody). Furthermore, it is possible that end points based solely on blood glucose, without considering information on insulin secretion, cannot distinguish the predominant diabetogenic mechanisms (e.g., type 1 vs. type 2 diabetes) in autoantibody-positive individuals who progress to diabetes. In this regard, Index60, a combined measure of C-peptide and glucose levels, could be more specific for predicting or diagnosing diabetes due to autoimmune loss of β-cells (50).

Investigations to prevent the decline in β-cell function before and after the clinical onset of type 1 diabetes may need to also address nonautoimmune pathways that could add to or perhaps amplify the autoimmune response. This could lead to the development of adjuvants that complement immunomodulatory therapies. This personalized approach would involve incorporating therapies that target diabetogenic mechanisms regulated by TCF7L2 or GLIS3 gene variants. Similarly, the addition of lifestyle and behavioral modifications (e.g., for controlling body weight) may be warranted in certain individuals in order to delay the onset of type 1 diabetes and further deterioration of β-cell function.

The involvement of type 2 diabetes–related genetic factors and obesity in the development of type 1 diabetes also poses difficulties for diagnosis and treatment. Clinicians may realize that both type 1 and type 2 mechanisms are present in certain individuals. Classifying these cases as just one type may overlook pathologic pathways (e.g., rapid β-cell loss or insulin resistance) that require therapy. Because β-cell preservation has been demonstrated to improve clinical outcomes in individuals with type 1 diabetes, preventing and managing obesity/overweight and providing treatments specific to other type 2 diabetes pathways (e.g., those regulated by TCF7L2 gene variants) may be warranted in order to protect β-cells from further damage.

Conclusions

Evidence is accumulating that factors such as obesity or type 2 diabetes–associated genes that regulate insulin secretion or action may play a role in the development and progression of type 1 diabetes, and their relative importance increases with age at diagnosis. We hypothesize that, at least in certain subsets of individuals, diabetes might be the result of the sum of autoimmune and nonautoimmune influences, their interactions, or both. In cases where the autoimmune component is only mild, type 2 diabetes–associated factors could take on a decisive role in the development of clinical diabetes. Recognizing the role of type 2 diabetes mechanisms in some individuals will improve our ability to predict progression to clinical disease among those at risk for type 1 diabetes, shed light on current challenges of diagnosing the type of diabetes, and open new opportunities to design personalized approaches for treating and preventing this disease.

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Amanda Posgai, University of Florida Diabetes Institute, for contributing to the discussion and providing an editorial review of the manuscript. The authors apologize to those researchers whose valuable work could not be cited because of constraints on the number of references allowed.

Funding. M.J.R. is partly supported by the National Institutes of Health-National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (U01 DK103180-01). C.E.-M. is supported by the National Institutes of Health-NIDDK (grant nos. R01 DK093954 and P30 DK097512), a Veterans Affairs Merit Award (I01BX001733), and a Strategic Research Agreement from JDRF (2-SRA-2018-493-A-B). C.E.-M. is also supported by gifts from the Sigma B Sorority, the Ball Brothers Foundation, the George and Frances Ball Foundation, the Holiday Management Foundation, the Thomas Trust, and the Weise family. A.K.S. is partly supported by National Institutes of Health-NIDDK (grant no. DK094712). M.A.A. is supported by the National Institutes of Health (P01 AI42288, U54 HL142766, and UC4 DK108132), JDRF, the Jeffrey Keene Family Professorship, and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Imperatore G, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, et al.; SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group . Projections of type 1 and type 2 diabetes burden in the U.S. population aged <20 years through 2050: dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality, and population growth. Diabetes Care 2012;35:2515–2520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas NJ, Jones SE, Weedon MN, Shields BM, Oram RA, Hattersley AT. Frequency and phenotype of type 1 diabetes in the first six decades of life: a cross-sectional, genetically stratified survival analysis from UK Biobank. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:122–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Insel RA, Dunne JL, Atkinson MA, et al. Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: a scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2015;38:1964–1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bingley PJ, Wherrett DK, Shultz A, Rafkin LE, Atkinson MA, Greenbaum CJ. Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet: a multifaceted approach to bringing disease-modifying therapy to clinical use in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2018;41:653–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leete P, Mallone R, Richardson SJ, Sosenko JM, Redondo MJ, Evans-Molina C. The effect of age on the progression and severity of type 1 diabetes: potential effects on disease mechanisms. Curr Diab Rep 2018;18:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Diabetes Association 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care 2019;42(Suppl. 1):S13–S28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redondo MJ, Steck AK, Pugliese A. Genetics of type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2018;19:346–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perry DJ, Wasserfall CH, Oram RA, et al. Application of a genetic risk score to racially diverse type 1 diabetes populations demonstrates the need for diversity in risk-modeling. Sci Rep 2018;8:4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant SF, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, et al. Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 2006;38:320–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackman SM, Hsu S, Ritter SE, et al. A susceptibility gene for type 2 diabetes confers substantial risk for diabetes complicating cystic fibrosis. Diabetologia 2009;52:1858–1865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin T. Current understanding on role of the Wnt signaling pathway effector TCF7L2 in glucose homeostasis. Endocr Rev 2016;37:254–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia Q, Chesi A, Manduchi E, et al. The type 2 diabetes presumed causal variant within TCF7L2 resides in an element that controls the expression of ACSL5. Diabetologia 2016;59:2360–2368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redondo MJ, Muniz J, Rodriguez LM, et al. Association of TCF7L2 variation with single islet autoantibody expression in children with type 1 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2014;2:e000008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redondo MJ, Geyer S, Steck AK, et al.; Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group . TCF7L2 genetic variants contribute to phenotypic heterogeneity of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2018;41:311–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redondo MJ, Grant SF, Davis A, Greenbaum C; T1D Exchange Biobank . Dissecting heterogeneity in paediatric type 1 diabetes: association of TCF7L2 rs7903146 TT and low-risk human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes. Diabet Med 2017;34:286–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redondo MJ, Steck AK, Sosenko J, et al.; Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group . Transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene polymorphism and progression from single to multiple autoantibody positivity in individuals at risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2018;41:2480–2486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timpson NJ, Lindgren CM, Weedon MN, et al. Adiposity-related heterogeneity in patterns of type 2 diabetes susceptibility observed in genome-wide association data. Diabetes 2009;58:505–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bingley PJ, Boulware DC, Krischer JP; Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group . The implications of autoantibodies to a single islet antigen in relatives with normal glucose tolerance: development of other autoantibodies and progression to type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2016;59:542–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen X, Yang Y. Emerging roles of GLIS3 in neonatal diabetes, type 1 and type 2 diabetes. J Mol Endocrinol 2017;58:R73–R85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frohnert BI, Laimighofer M, Krumsiek J, et al. Prediction of type 1 diabetes using a genetic risk model in the Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young. Pediatr Diabetes 2018;19:277–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steck AK, Xu P, Geyer S, et al.; Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group . Can non-HLA single nucleotide polymorphisms help stratify risk in TrialNet relatives at risk for type 1 diabetes? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:2873–2880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winkler C, Krumsiek J, Buettner F, et al. Feature ranking of type 1 diabetes susceptibility genes improves prediction of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2014;57:2521–2529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liston A, Todd JA, Lagou V. Beta-cell fragility as a common underlying risk factor in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Trends Mol Med 2017;23:181–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkin TJ. The accelerator hypothesis: weight gain as the missing link between type I and type II diabetes. Diabetologia 2001;44:914–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knerr I, Wolf J, Reinehr T, et al.; DPV Scientific Initiative of Germany and Austria . The ‘accelerator hypothesis’: relationship between weight, height, body mass index and age at diagnosis in a large cohort of 9,248 German and Austrian children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 2005;48:2501–2504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dabelea D, D’Agostino RB Jr., Mayer-Davis EJ, et al.; SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group . Testing the accelerator hypothesis: body size, beta-cell function, and age at onset of type 1 (autoimmune) diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006;29:290–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Couper JJ, Beresford S, Hirte C, et al. Weight gain in early life predicts risk of islet autoimmunity in children with a first-degree relative with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:94–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu P, Cuthbertson D, Greenbaum C, Palmer JP, Krischer JP; Diabetes Prevention Trial-Type 1 Study Group . Role of insulin resistance in predicting progression to type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2314–2320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sosenko JM, Skyler JS, Mahon J, et al.; Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet and Diabetes Prevention Trial-Type 1 Study Groups . Use of the Diabetes Prevention Trial-Type 1 Risk Score (DPTRS) for improving the accuracy of the risk classification of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014;37:979–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meah FA, DiMeglio LA, Greenbaum CJ, et al.; Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group . The relationship between BMI and insulin resistance and progression from single to multiple autoantibody positivity and type 1 diabetes among TrialNet Pathway to Prevention participants. Diabetologia 2016;59:1186–1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elding Larsson H, Vehik K, Haller MJ, et al.; TEDDY Study Group . Growth and risk for islet autoimmunity and progression to type 1 diabetes in early childhood: The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young study. Diabetes 2016;65:1988–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkin TJ. The accelerator hypothesis: a review of the evidence for insulin resistance as the basis for type I as well as type II diabetes. Int J Obes 2009;33:716–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrara CT, Geyer SM, Liu YF, et al.; Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group . Excess BMI in childhood: a modifiable risk factor for type 1 diabetes development? Diabetes Care 2017;40:698–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tchernof A, Despres JP. Sex steroid hormones, sex hormone-binding globulin, and obesity in men and women. Horm Metab Res 2000;32:526–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Censin JC, Nowak C, Cooper N, Bergsten P, Todd JA, Fall T. Childhood adiposity and risk of type 1 diabetes: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunmore SJ, Brown JE. The role of adipokines in β-cell failure of type 2 diabetes. J Endocrinol 2013;216:T37–T45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marhfour I, Lopez XM, Lefkaditis D, et al. Expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress markers in the islets of patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2012;55:2417–2420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marroqui L, Dos Santos RS, Op de Beeck A, et al. Interferon-α mediates human beta cell HLA class I overexpression, endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis, three hallmarks of early human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2017;60:656–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomaidou S, Zaldumbide A, Roep BO. Islet stress, degradation and autoimmunity. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018;20(Suppl. 2):88–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tosur M, Redondo MJ, Lyons SK. Adjuvant pharmacotherapies to insulin for the treatment of type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 2018;18:79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Helman A, Avrahami D, Klochendler A, et al. Effects of ageing and senescence on pancreatic β-cell function. Diabetes Obes Metab 2016;18(Suppl. 1):58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 2012;149:274–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verdin E. NAD+ in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration. Science 2015;350:1208–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mishra R, Hodge KM, Cousminer DL, Leslie RD, Grant SFA. A global perspective of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2018;29:638–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar A, de Leiva A. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) in Asian and European populations. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2017;33:e2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cousminer DL, Ahlqvist E, Mishra R, et al.; Bone Mineral Density in Childhood Study . First genome-wide association study of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults reveals novel insights linking immune and metabolic diabetes. Diabetes Care 2018;41:2396–2403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu L, Li X, Xiang Y, et al.; LADA China Study Group . Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults with low-titer GAD antibodies: similar disease progression with type 2 diabetes: a nationwide, multicenter prospective study (LADA China Study 3). Diabetes Care 2015;38:16–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pieralice S, Pozzilli P. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults: a review on clinical implications and management. Diabetes Metab J 2018;42:451–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Redondo MJ, Geyer S, Steck AK, et al.; Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group . A type 1 diabetes genetic risk score predicts progression of islet autoimmunity and development of type 1 diabetes in individuals at risk. Diabetes Care 2018;41:1887–1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nathan BM, Boulware D, Geyer S, et al.; Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet and Diabetes Prevention Trial–Type 1 Study Groups . Dysglycemia and Index60 as prediagnostic end points for type 1 diabetes prevention trials. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1494–1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]