Abstract

The detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis‐specific antibodies in human sera has been a rapid and important diagnostic aid for tuberculosis (TB) control and prevention. However, any single antigen is not enough to be used to cover the antibody profiles of all TB patients. In this study, a novel fusion protein was constructed using gene splicing by overlap extension (SOEing), and then the antibody level against it in 171 TB patients and 86 controls was evaluated by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay. Compared with the three individual antigen (16 kDa: sensitivity 19.9%, specificity 96.5%; MPT64: sensitivity 75.4%, specificity34.9%; 38 kDa: sensitivity 33.3%, specificity 83.7%), the fusion protein antigen (sensitivity 42.1%, specificity 89.5%) gave the best diagnostic performance with the largest receiver operating characteristic curve area 0.656 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.590–0.721; P<0.01). These results suggested that the novel fusion protein antigen successfully constructed by gene SOEing provided the improved diagnostic performance for TB, and other mycobacterial multiepitope fusion proteins may also be worthy of investigation for further enhancing the detection sensitivity. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 25:344–349, 2011. © 2011 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Rv2031c, Rv1980c, Rv0934, fusion protein, ROC

INSTRUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the greatest health care problems in the world. In 2009, there were 9.4 million new TB cases, including 1.1 million cases among people with HIV 1. The development of a rapid and accurate test for the diagnosis is a priority for TB control. Importantly, the search for the specific biomarkers of TB and the marriage of biomarkers has still been the focus of detection sensitivity 2, 3, 4. Accordingly, our previous studies reported a new candidate antigen Rv3425 5, 6 and then it was used to develop a novel multi‐antigen enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test (sensitivity 61.8% and specificity 93.0%) together with other two well‐known immunodominant antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) 7.

Alternatively, it would be an effective strategy to design recombinant fragments and express novel fusion protein antigens according to the reported immunodominant antigens of M. tuberculosis. In this study, a novel fusion fragment from M. tuberculosis Rv2031c (hspX), Rv1980c (mpt64), and Rv0934 (pstS1) genes were analyzed by bioinformatics and found having potential diagnostic value. The 16 kDa (HspX) antigen is a cytosolic regulatory protein specific to the M. tuberculosis complex, and is essential for the survival of the bacilli in the hostile environment of the host, particularly during latency 8. MPT64 and the 38 kDa (PstS1) are also immunodominant antigens for serodiagnosis of TB 9, 10. Accordingly, the fusion fragment was expressed as an antigen with multiepitopes, and then the fusion protein antigen was evaluated for serodiagnosis of TB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Two hundred and fifty‐seven serum samples (n=257) from HIV‐seronegative individuals were studied. Serum samples (n=171) from active TB patients (age range: 3–77 years) were collected at Linyi Chest Hospital, Shandong, China. There were 94 men and 77 women, but only 138 patients had the positive tuberculin skin test (TST) when the serum samples were taken. In this study, active TB patients were confirmed by the isolation and identification of M. tuberculosis 11, 12, as well as clinical and radiological findings. They were classified into three groups: (i) smear‐positive for acid‐fast bacilli and culture‐positive pulmonary TB (n=63); (ii) smear‐negative culture‐positive pulmonary TB (n=74); and (iii) extra‐pulmonary TB (n=34). All the patients had not yet started anti‐TB chemotherapy when the serum samples were taken.

Serum samples (n=86) were also obtained from non‐TB patients (age range: 10–86 years) and healthy donors (age range: 1–55 years) at the same hospital and used as controls. There were 44 men and 42 women, but only 24 subjects had the positive TST when the serum samples were taken. All the control subjects had no TB previously, and had negative chest X‐rays and negative sputum culture results for M. tuberculosis. Sera were stored at −20°C.

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of the Fusion Protein

The fusion protein was cloned and expressed using gene splicing by overlap extension (Gene SOEing) method, as previously described 13. Briefly, the gene fragments of Rv2031c (GenBank identifier (GI): 15609168), Rv1980c (GI: 15609117), and Rv0934 (GI: 57116801) were obtained by PCR with genomic DNA of M . tuberculosis H37Rv strains as template; the primers and parameters for thermal cycle amplification are shown in Table 1. Then, the fusion gene fragment was obtained by PCR with above PCR products as templates and with SOE‐1 and SOE‐6 as primers, and was cloned at the Xho I and Nco I sites of the cloning vector pET30a with six N‐terminal histidine sequence tags. The clones were confirmed by sequencing (Sangon Sequencing Facility, Shanghai, China) and the construct was then transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain (Novagen, Madison, WI) for the fusion protein expression. Finally, the overexpressed His‐tagged fusion protein was purified from the soluble cellular materials contained in 1,000 ml of isopropyl‐b‐d‐thiogalactopyranoside‐induced batch cultures by Ni‐NTA His‐binding resin affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer's protocol (Bio‐Rad Laboratories Ltd., Shanghai, China). After dialyzing against 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, containing 100 mM NaCl and glycerol 3% (v/v), the purity and the content of the fusion protein were assessed by SDS‐PAGE analysis and Bradford's assay (14), respectively.

Table 1.

PCR Primers and Thermal Cycle Parameters for Amplification

| Template | Fragment | Primer | Sequence | Enzyme sites | PCR parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fRv2031c | SOE‐1 | 5′catgccatggagatgaaagaggggcgctacg 3′a | Nco I | 94°C for 5 min | |

| SOE‐2b | 5′cgcgtggagtgccaccgccaccttcggttggcttcccttccg 3′ | – | Then 30 cycles | ||

| Genomic DNA of | fRv1980c | SOE‐3b | 5′ggcggtggcactccacgcgaagccccc 3′ | – | 94°C for 45 sec |

| M. tuberculosis H37Rv | SOE‐4c | 5′cgtcccagccaccgccaccgttcgtgactgcgaagttctg 3′ | – | 62°C for 45 sec | |

| fRv0934 | SOE‐5c | 5′ggcggtggctgggacgacccgcagatcg 3′ | – | 72°C for 45 sec | |

| SOE‐6 | 5′agctcgagctatttcgatgcgaagccagccg 3′a | Xho I | Then 72°C for 10 min |

aUnderlined are restriction enzyme cut sites.

bSOE‐2 and SOE‐3 are two complemented primers.

cSOE‐4 and SOE‐5 are two complemented primers.

ELISA and Data Analysis

The ELISA was performed as previously described 7 except that polystyrene flat‐bottom microtiter plates (Costar) were coated (100 μl/well) with the concentration of 2.0 μg/ml fusion antigen, 5.0 μg/ml of 38 kDa antigen (ImmunoDiagnostics, Inc., Woburn, MA), and 5.0 μg/ml of 16 kDa antigen or 2.5 μg/ml of MPT64 (Fudan University, Shanghai, China), respectively.

The differences between the values for the groups were analyzed by Student t‐test. A level of statistical significance of P<0.05 was accepted. For analyzing the behavior of diagnostic performance, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to organize and select classifiers based on their performance, according to the previous studies 15, 16. In addition, the optimal cutoff values were chosen when Youden's index (sensitivity+specificity −1) was maximal. Subsequently, individual was scored as positive for the specific antibody response when its optical density value was greater than or equal to the cutoff value. All data were analyzed using the Statistical Program for Social Sciences 13.0 software program (SPSS, Inc., Chicago).

RESULTS

Expression and Purification of the His‐Tagged Fusion Protein

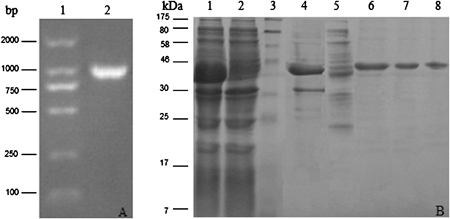

Three separate PCR‐generated sequences (fRv2031c, fRv1980c, fRv0934) were joined together and formed a recombinant molecule. The molecular weight indicated by agarose gel electrophoresis was above 1,000 bps (Fig. 1A), which was close to the theoretical value (1,040 bps). Then, the corresponding fusion gene fragment was cloned to the vector pET30a and was confirmed by sequencing. After the expression vector was constructed and expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain, the His‐tagged fusion protein was purified and fractionated by electrophoresis on a 12% polyacrylamide gel. A single band was observed on the staining gel with coomassie brilliant blue dye (Fig. 1B). Because the fusion protein was largely present in the soluble fraction, the purification was carried out under native conditions from soluble fractions with a yield of 8.3 mg of protein per liter of culture. Finally, the His‐tagged fusion protein was purified to >95% homogeneity on a nickel affinity column and was used for immunoreactivity analyses.

Figure 1.

The analysis of the final PCR product (1,040 bps) (A) and the fusion protein purification (B). (A) 1. DNA marker (Watson Biotechnologies, Shanghai, China); 2. PCR product, and (B) lane 1, the induced BL21 cells; lane 2, the non‐induced BL21 cells; lane 3, molecular weight marker (P7708, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), Lane 4, insoluble fraction of BL21 (DE3) transformed with the fusion plasmid; lane 5, soluble fraction of BL21 (DE3) transformed with the fusion plasmid; lane 6–8, purified fusion proteins. Proteins were visualized with Coomassi brilliant blue staining.

ELISA Assays for IgG Antibodies

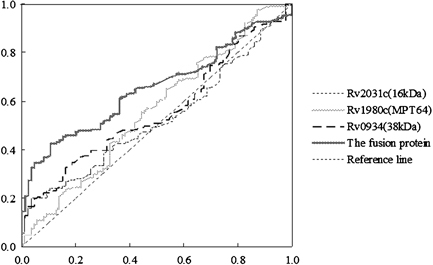

Individual values of antibodies against 16 kDa, MPT64, 38 kDa, and the fusion protein antigen were used for the generation of ROC curves (Fig. 2). The areas under the curves and 95% CIs were calculated in Table 2. Compared with ROC area under the curve provided by the individual antigens (16 kDa: 0.523; MPT64: 0.561; 38 kDa: 0.559), the ROC area achieved by the fusion antigen was higher, 0.656 (95% CI, 0.590–0.721; P<0.01), indicating a higher level of overall accuracy. Accordingly, the optimal cutoff values of the optical densities of antibody responses to the 16 kDa, MPT64, 38 kDa, and the fusion protein antigen for diagnosing TB patients were 0.343, 0.102, 0.264, and 0.278, respectively. As a result, in 171 TB patients and 86 controls, the sensitivities of detecting antibody responses to the 16 kDa, MPT64, 38 kDa, and the fusion protein antigen were 19.9, 75.4, 33.3, and 42.1%, respectively, and the specificities were 96.5, 34.9, 83.7, and 89.5%, respectively (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Evaluation of four antigens using ELISA by Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curves.

Table 2.

Area Under the ROC Curve

| Asymptotic 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test result variable(s) | Area | Standard errora | Asymptotic sig.b | Lower bound | Upper bound |

| 16 kDa (Rv2031c) | 0.523 | 0.037 | 0.539 | 0.452 | 0.595 |

| MPT64 (Rv1980c) | 0.561 | 0.038 | 0.112 | 0.485 | 0.636 |

| 38 kDa (Rv0934) | 0.559 | 0.036 | 0.122 | 0.488 | 0.630 |

| The fusion protein | 0.656 | 0.034 | 0.000 | 0.590 | 0.721 |

aUnder the nonparametric assumption.

bNull hypothesis: true area=0.5.

Table 3.

Sensitivities and Specificities of ELISA Assays for IgG Antibodies Against 16 kDa, MPT64, 38 kDa, and the Fusion Protein Antigen, Respectively

| 16 kDa | MPT64 | 38 kDa | Fusion protein | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivitya | ||||

| Total (n=171) | 19.9% (34) | 65.5% (112) | 33.3% (57) | 42.1% (72) |

| Smear positive TB (n=63) | 31.7% (20) | 87.3% (55) | 52.4% (33) | 57.1% (36) |

| Smear negative TB (n=74) | 9.5% (7) | 71.6% (53) | 27.0% (20) | 28.4% (21) |

| Extra‐pulmonary TB (n=34) | 20.6% (7) | 11.8% (4) | 11.8% (4) | 44.1% (15) |

| Specificityb | ||||

| Total (n=86) | 96.5% (83) | 34.8% (30) | 83.7% (72) | 89.5% (77) |

| Non‐TB diseases (n=38) | 92.1% (35) | 36.8% (14) | 86.8% (33) | 92.1% (35) |

| Healthy control (n=48) | 100.0% (48) | 33.3% (16) | 81.3% (39) | 87.5% (42) |

aSensitivity was determined by dividing the number of positive cases by the total number of TB patients.

bSpecificity was determined by dividing the number of negative controls by the total number of controls.

No statistically significant difference was found among the subgroups in TB patients for factors associated with TB risk, such as age, gender, and TST test (data not shown). On the other hand, the sensitivities of antibody detection with each of the three individual antigens were 9.5–31.7%, 11.8–87.3%, and 11.8–52.4% in the subgroup TB patients, respectively. But that with the fusion antigen was 57.1% in 63 smear‐positive pulmonary TB, 28.4% in 74 smear‐negative pulmonary TB, and 44.1% in 34 extra‐pulmonary TB (Table 3). With respect to the non‐TB disease (n=38) and healthy controls (n=48), none to 32 serum samples from them reacted against one of the three individual antigens; only three and six serum samples showed antibodies to the fusion protein antigen, respectively.

The results between the fusion antigen ELISA and multi‐antigen ELISA were also analyzed. The detection criteria of the multi‐antigen ELISA were set; i.e., the serum tested was determined to be TB positive if any two or three antigens (16 kDa, MPT64, 38 kDa) specifically reacted with it. In total, the sensitivity estimate for the fusion antigen test was 42.1% (72/171), which was a little lower than the estimate for the combined antigen (44.4%, 76/171), but the specificity estimate for the fusion antigen test was 89.5% (77/86), higher than that for the combined antigen (83.5%, 72/86) (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

It would be an effective strategy to design recombinant fragments and express novel fusion protein antigens, according to the reported immunodominant antigens of M. tuberculosis (9) for serodiagnosis of TB. In this study, a novel fusion protein antigen (fRv2031c+fRv1980c+fRv0934) of M. tuberculosis was successfully constructed with multiepitopes by gene SOEing method. Of the 63 sera from smear‐positive pulmonary TB patients, 36 (57.1%) had antibodies to the fusion antigen. Furthermore, among the most problematic cases in terms of diagnosis (smear‐negative pulmonary TB and extra‐pulmonary TB patients), TB antibodies were detectable in a small proportion of patients (<28%) with individual antigen, except MPT64 (71.6%). However, they were detectable with the fusion protein antigen in a larger proportion, i.e., 28.4% (21/74) for smear‐negative pulmonary TB patients and 44.1% (15/34) for extra‐pulmonary TB patients. Of all the 171 active TB patients, the total detection sensitivity of the combination of the three antigens was 44.4% (76/171), and almost the same sensitivity was achieved by the use of fusion protein antigen, but the total detection specificity of the fusion protein antigen was improved to 89.5%. The optimal cutoff values in the study were chosen when Youden's index was maximal. But, looking at ROC curve it could be found better sensitivity and specificity for single MPT64, approximately 42% and 66%, respectively. Accordingly, the fusion protein antigen seems to overcome cross‐reactivity, probably mainly related to MPT64, without changing the sensitivity.

The area under the ROC curve of the fusion protein antigen ELISA was 0.656 (95% CI, 0.590–0.721; P<0.01) in this study, suggesting a better overall diagnostic performance than the three individual antigens. On the other hand, the positive result of the TST test is often considered as latent infection in China. In this study, 24 of the control subjects were TST positive while 62 of them were TST negative when the serum samples were taken. However, our results showed no statistically significant difference between TST positive and TST negative controls for the test; this may be owing to the use of the specific selected antigens. In addition, the smear‐positive pulmonary TB patients were almost (90.5%, 57/63) associated with severe disease (based on X‐ray findings) in the study. Of the sera from 63 smear‐positive pulmonary TB patients, 40 sera were tested as positive in TB patients by the combination of the three antigens, of which 31 sera were also tested as TB positive by the fusion protein antigen, whereas another 5 sera were tested as TB positive only by the fusion protein (data not shown). Therefore, the constructed fusion protein revealed the same association.

However, this study also has several limitations. First, serum samples from healthy control subjects were lack of sera from patients in whom pulmonary TB was initially suspected, but who were later found to have nontuberculous respiratory disease or more exposed individuals (such as in high TB endemic area), and this may result in overestimate specificity of the fusion protein antigen assay. Second, our results showed no statistically significant difference between TST positive and TST negative controls. But the criteria for defining subjects with known TB contact or TB latent infection based on the TST result may have some flaws; further investigation would be under way together with other criteria, such as interferon gamma release assays. Third, the clinical technicians performed the tests not in a double blind manner, meaning their test reading were not blinded to patient diagnosis or results of the culture when using the fusion protein antigen ELISA (blinded to diagnosis and study group).

In conclusion, a recombinant fragment from M. tuberculosis H37Rv Rv2031c, Rv1980c and Rv0934 genes was successfully expressed as a novel fusion protein. The ROC analysis indicated that the fusion protein antigen had a better overall diagnostic performance than the three individual antigens. However, further improvement in the sensitivity of such a serological test is imperative and other mycobacterial multiepitope fusion proteins may be also worthy of investigation.

Contributor Information

Yu‐Feng Liu, Email: cz711010@163.com.

Shu‐Lin Zhang, Email: slzhang@shsmu.edu.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO . Multidrug and Extensively Drug‐Resistant TB (M/XDR‐TB): 2010 Global Report on Surveillance and Response. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. (WHO/HTM/TB/2010.2013). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shen G, Behera D, Bhalla M, Nadas A, Laal S. Peptide‐based antibody detection for tuberculosis diagnosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2009;16:49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sumi S, Radhakrishnan VV. Diagnostic significance of humoral immune responses to recombinant antigens of mycobacterium tuberculosis in patients with pleural tuberculosis. J Clin Lab Anal 2010;24:283–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McNerney R, Daley P. Towards a point‐of‐care test for active tuberculosis: Obstacles and opportunities. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011;9:204–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang HM, Wang JL, Lei JQ, et al. PPE protein (Rv3425) from DNA segment RD11 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A potential B‐cell antigen used for serological diagnosis to distinguish vaccinated controls from tuberculosis patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 2007;13:139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang JL, Qie YQ, Zhang HM, et al. PPE protein (Rv3425) from DNA segment RD11 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A novel immunodominant antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces humoral and cellular immune responses in mice. Microbiol Immunol 2008;52:224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang SL, Zhao JW, Sun ZQ, et al. Development and evaluation of a novel multiple‐antigen ELISA for serodiagnosis of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 2009;89:278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Demissie A, Leyten EM, Abebe M, et al. Recognition of stage‐specific mycobacterial antigens differentiates between acute and latent infections with Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Clin Vaccine Immunol 2006;13:179–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oettinger T, Andersen AB. Cloning and B‐cell‐epitope mapping of MPT64 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Infect Immun 1994;62:2058–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Young D, Kent L, Rees A, Lamb J, Ivanyi J. Immunological activity of a 38‐kilodalton protein purified from Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Infect Immun 1986;54:177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang SL, Shen JG, Shen GH, et al. Use of a novel multiplex probe array for rapid identification of Mycobacterium species from clinical isolates. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2007;23:1779–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Metchock B, Nolte FS, Wallace RJ. Mycobacterium. In: Murray PR, Baron EJ, Pfaller MA, Tenover FC, Yolken RH, editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology, seventh edition Washington, DC: ASM Press; 1999. p 399–437. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Horton RM. PCR‐mediated recombination and mutagenesis. SOEing together tailor‐made genes. Mol Biotechnol 1995;3:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein‐dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976;72:248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Swets JA. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 1988;240:1285–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kashyap RS, Rajan AN, Ramteke SS, et al. Diagnosis of tuberculosis in an Indian population by an indirect ELISA protocol based on detection of Antigen 85 complex: A prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2007;7:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]