Abstract

This article reports 2-year outcomes from a cluster randomized controlled trial of the Early Risers (ER) program implemented as a selective preventive intervention in supportive housing settings for homeless families. Based on the goals of this comprehensive prevention program, we predicted that intervention participants receiving ER services would show improvement in parenting and child outcomes relative to families in treatment-as-usual sites. The sample included 270 children in 161 families, residing in 15 supportive housing sites; multi-method, multi-informant assessments conducted at baseline and yearly thereafter included parent and teacher report of child adjustment, parent report of parenting self-efficacy, and parent-child observations that yielded scores of effective parenting practices. Data were modeled in HLM7 (4 level model accounting for nesting of children within families and families within housing sites). Two years post-baseline, intent-to-treat/ITT analyses indicated that parents in the ER group showed significantly improved parenting self-efficacy, and parent report indicated significant reductions in ER group children’s depression. No main effects of ITT were shown for observed parenting effectiveness. However, over time, average levels of parenting self-efficacy predicted observed effective parenting practices, and observed effective parenting practices predicted improvements in both teacher- and parent-report of child adjustment. This is the first study that we know of to demonstrate prevention effects of a program for homeless families residing in family supportive housing.

Keywords: homeless families/children, supportive housing, prevention, Early Risers, parenting

Introduction

Effectiveness trials of family-based prevention programs offer the potential to extend the generalizability of prevention practices to new populations, and hitherto overlooked risk contexts. Homelessness represents one such risk context. Homeless families - typically comprising a mother with two or more young children per family - were the most rapidly growing segment of the homeless population in the first decade of this century (US Department of Housing and Urban Development/HUD, 2008).

Furthermore, recent decreases in the homeless population have not extended to families, who in 2012 accounted for nearly 38% of the homeless population (HUD, 2013).

In addition to facing the challenges of homelessness (i.e. housing and food insecurity, hunger, extreme poverty, instability of educational setting), children in homeless families are likely to experience related contextual risks, such as exposure to violence, parental mental health problems, and child protection involvement (Anooshian, 2005; Shinn, Rog, & Culhane, 2006). These place children at high risk for social, emotional and behavioral problems (e.g. Lee et al., 2010; Kilmer, Cook, Crusto, Strater, & Haber, 2012). Moreover, the impact of homelessness on children’s adjustment appears to extend beyond the period of homelessness itself. For example, formerly homeless children living in family supportive housing show high rates of exposure to child maltreatment, parental substance abuse, and parental mental illness (Gewirtz, Hart- Shegos, & Medhanie, 2008). Rates of behavioral and emotional difficulties among these children appear to be greater than those in low SES housed families, and comparable to children identified with behavior and conduct problems in the permanently housed community (Lee et al., 2010). Overall, these data are consistent with research on childhood adversity that documents both concurrent and future negative health consequences of adverse or toxic childhood experiences (e.g. Shonkoff et al., 2012).

Developmental research from a social interaction learning perspective has demonstrated how stressful family contexts (e.g. parental psychopathology, substance use, family transitions) provide fertile ground for the development of child behavior problems and depression via impaired parenting practices. For example, Patterson (1982) documented an ‘early starter’ antisocial trajectory that begins with disruptive behavior in early childhood and the elementary years, and continues with peer rejection, depressive symptoms, deviant peer association, and escalating conduct problems (e.g., delinquency, truancy, drug use, risky sexual behavior) in adolescence, and disrupted work placements, hospitalizations and/or jail time in adulthood. Coercive parenting practices predict child antisocial behavior; conversely, positive parenting practices have been shown to reduce child behavior problems and depression (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999).

Parenting practices (i.e. behaviors used to socialize and teach children, including discipline, problem-solving, monitoring, positive involvement, and encouragement) are particularly important for their influence on child adjustment when families are living in high-risk circumstances (e.g., Forgatch & Patterson, 1999; Masten et al., 1999; Werner & Smith, 1992). Relatively little research, most of it cross-sectional, has been conducted on parenting in homeless families, but extant data suggest that homelessness may be associated with impaired parenting practices. In a small sample of 77 sheltered homeless preschoolers, parent reports of their own parenting (measured with the Parenting Practices Scale; Strayhorn, Strayhorn, & Weidman, 1988), were associated with parent- reported behavior problems on the Child Behavior Checklist; Bassuk et al., 1997). Koblinsky, Morgan, and Anderson (1997) reported homeless mothers of young children as providing a less structured environment, stimulation for learning, and warmth and acceptance, compared to housed mothers.

Parenting self-efficacy – parents’ cognitions about their ability to influence their children’s behavior and development (Jones & Prinz, 2005) – appears to be key to effective parenting practices, and also may be undermined by homelessness. Using a cross-lagged longitudinal design with a sample of 189 Mexican-American families with adolescents, Dumka, Gonzales, Wheeler, & Millsap (2010) found higher parenting self- efficacy to predict subsequent positive parental control and reduced youth conduct problems. Earlier data from an economically disadvantaged sample of inner-city families indicated that economic hardship negatively impacted parenting self-efficacy (Elder, Eccles, Ardelt, and Lord, 1995). However, even among this disadvantaged sample, parents with a strong sense of parenting self-efficacy demonstrated more effective teaching, monitoring, and discipline strategies with their children. In a sample of 127 homeless mothers, higher parenting self-efficacy was significantly positively associated with observed effective parenting practices (i.e. discipline, problem-solving, encouragement, warmth), and parent reports of child adjustment (Gewirtz et al., 2009).

Although homeless families would appear to be prime populations for psychosocial prevention programs aimed at reducing child behavior problems and depression, and improving parenting competencies, few such programs have been rigorously evaluated (e.g., Perlman et al, 2012; Gewirtz, Burkhart, Loehman, & Haukebo, 2014; Herbers & Cutuli, 2014). This is not surprising given the high mobility of homeless families and the short-term nature of most shelters. However, an emerging solution to the increasing problem of family homelessness – family supportive housing –provides a unique opportunity for prevention (Gewirtz, 2007). Supportive housing provides longer- term subsidized housing (up to 18 months and beyond) with case management services for families who have experienced long-term homelessness and have caregivers with disabilities (HUD, 2014). Because supportive housing is often provided in clustered sites, this resource provides a potentially efficient portal for the provision of psychosocial prevention programming (Gewirtz & August, 2008).

In this paper, we report outcome data from an effectiveness trial of Early Risers, an empirically-supported, theory-based intervention originally developed to reduce child conduct problems among those children identified as demonstrating behavior problems in kindergarten (i.e. an indicated prevention program). In the current study, we tested the effectiveness of Early Risers as a selective prevention program (i.e. targeting those children at risk for behavior problems and depression by virtue of their exposure to homelessness) for formerly homeless families living in supportive housing.

The Early Risers “Skills for Success” Prevention Program

Early Risers (ER) was originally designed to interrupt the ‘early-starter’ pathway to antisocial behavior (Moffitt, 1993; Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989) using social cognitive and social interaction learning approaches to intervention. Program goals are accomplished by affecting positive growth in child, parent, and family competencies that act to buffer the relations between early child, parent, and family risk factors and the subsequent development of youth conduct and associated problems (i.e. depression). The intervention design includes two complementary components, ‘child’ and ‘family’, delivered in tandem over a two- to three-year period. Each component offers individual program elements that address multiple competence domains (e.g., child social skills, parenting behavioral management skills) and social contexts (school support, family support) implicated in the “early-starter” pathway. The conceptual underpinnings of the components (grounded in social learning, social-cognitive, and social ecosystems theories) are fully described in August, Realmuto, Winters, and Hektner (2001). The theoretical constructs undergirding the components map onto conceptually-based malleable intervention targets including parent competence and resources (i.e. improved parenting practices and parenting self-efficacy), and child adjustment (i.e. reduced externalizing and depression problems).

The Current Study: Early Risers-Healthy Families Network (ER-HFN)

The ER-HFN study tested the effectiveness of the ER model on child- and parent outcomes in a cluster randomized trial conducted in a supportive housing context. Using an intent-to-treat approach, we evaluated the program’s impact on three target outcomes linked to child and family components: child adjustment (depression and externalizing behavior problems), parents’ cognitive psychological resources (i.e. parenting self- efficacy), and parenting practices. Specifically, hypotheses were as follows:

Compared to those in the services-as-usual condition, children in families assigned to the Early Risers program condition will show fewer behavioral and depression problems from baseline to 2-years post- baseline.

Compared to those in the services-as-usual condition, parents in families assigned to the Early Risers program condition will show improved parenting self-efficacy from baseline to 2-years post-baseline.

Compared to those in the services-as-usual condition, parents in families assigned to the Early Risers program condition will show improved observed effective parenting practices from baseline to 2- years post-baseline.

In addition, as an exploratory aim, we examined longitudinal associations among outcome variables, given earlier findings that mothers’ parenting self-efficacy was significantly associated with observed parenting practices, and child adjustment (Gewirtz et al., 2009).

Methods

Supportive housing sites

Participating sites were sixteen private, non-profit family supportive housing agencies, serving more than 95% of formerly homeless families resident in clustered family supportive housing in large metropolitan area in the Midwest. With one exception (a site which housed three of the families in this study)1 all sites provided private apartments for families, with multiple units in a building. Families were required to be homeless at the time of admission, and to demonstrate caregiver disability (typically mental illness/substance use disorder), or flight from domestic violence or prostitution.

Participants

The sixteen housing sites were randomly assigned to intervention or comparison conditions and in each site, over a one-year recruitment period, all caregivers living with at least one 6–12 year old child were invited to participate in the study. The flow of study participants by site allocation is presented in Figure 1 as a CONSORT chart (Altman et al., 2001). One of the 16 sites was dropped from the study during the recruitment phase because it had no families who were interested in participating. At baseline, 161 families with 270 children provided consent/assent to enroll in the program. Twenty-eight of these families (with 40 children) relocated or dropped out of the study immediately after recruitment and prior to baseline assessment. The attrition occurred across 11 sites (M=2.5 families, range=1–6). No significant group difference was detected between the two intervention conditions. Of the remaining 133 families (with 230 children), mean child age was 8.10 years (SD = 2.3), and 51% of children were girls. Sixty-six percent of the children had a sibling also in the study, and the number of children per family varied from 1 to 5 with a mean of 1.6 children per family. All of the participating families were single-headed, and families were overwhelmingly female-headed (98.5%). The number of families per study site ranged from 1 to 34 with a mean of 13.4 children per study site. Average annual parent income was $10,371.59 (SD = $5,486.73). On average, parents were high school graduates or equivalent (M = 11.98 years of education, SD = 1.61).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of study participant flow through housing site randomization, enrollment, baseline assessment, follow-up 1 and follow-up 2. Family retention rates based on numbers of Level 1 children assessed repeatedly over time.

Half of the families were African-American, 19% were Caucasian, 20% self-identified as multiracial, and 11% other minority groups (6% Native American, 3% Hispanic, 2% Asian).

Intervention Components

Early Risers is a multi-component prevention program consisting of child and family/parent components, delivered over a 2-year period starting and ending in the summer. Child component activities included an after school program, held two afternoons per week for 2 hours each time, and a six week, half-day summer camp held over three summers. Both child activities utilized the Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies/PATHS curriculum (Kusche & Greenberg, 1993), aimed at improving child social-emotional competence. In addition, a literacy curriculum was delivered in tandem with PATHS, focused on improving reading and comprehension skills (August et al., 2006). Tools used to improve reading skills, fluency and comprehension included (a) reading aloud with comprehension probes, (b) vocabulary building through key words from the books, and (c) lesson-related activity sheets. The family/parent components of Early Risers included family support services (case management) and quarterly Family Fun nights, aimed at offering information on key child development topics with parent- child activities and a meal provided. In the second program year, mothers were invited to participate in Parenting Through Change (PTC; Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999), a 14-week parent training program originally developed for separating and divorcing mothers and modified for this population (Gewirtz & Taylor, 2009). PTC aims to improve five core parenting skills – teaching through encouragement, discipline, problem-solving, monitoring, and positive involvement – and is delivered using active teaching (role play and discussion). PTC was delivered in a group format at each site. Families also were offered a school-based monitoring and mentoring program, aimed at improving home- school communication, helping parents to navigate children’s school needs, and school- based academic coaching. One hundred and eighteen children (94%) attended at least one after-school session with an average attendance of 49.9% (SD=25.9, range = 2–100). A total of 75 children (60%) attended at least one summer camp session and their average attendance was 65% (SD=30.4, range 5–100). On average, children received 20.47 hours of school-based monitoring and mentoring (SD = 21.89, range = 0.03 – 103.55). Sixty-eight parents (84%) attended at least one parent session (Family Fun nights or PTC) with average attendance of 7.96 sessions (SD = 5.80, range = 1–21). On average, parents received 7.63 hours of family support services (SD = 6.42, range = 0.08 – 27.27).

Interventionists

Four full-time family advocates, who were hired as employees of the housing agencies and had prior experience providing case management or advocacy services to homeless families, delivered the ER program. Their education levels varied from an associate’s degree to a bachelor’s degree. Each advocate was responsible for delivering program services at two housing sites. Advocates received training in the overall ER program, as well as specific training in PATHS, and in Parenting Through Change. Training involved in-person didactic presentation, coaching, and guided discussion along with role playing activities. Each family advocate received approximately 40 hours of initial training for all program components. Ongoing coaching was provided by the ER program manager via live observation facilitation and weekly feedback meetings.

Fidelity to the Early Risers intervention components was assessed using observational measures (Forgatch, Knutson, Rains, Sigmarsdottir, 2011; Lee et al., 2008). Fidelity of implementing PATHS and Family Fun nights was assessed using a 15-item checklist that measures ‘adherence-content’, ‘adherence-delivery’, and ‘quality of delivery’. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1=not at all to 5=nearly all the time. Categories were averaged across multiple observation points. Mean scores for PATHS were 4.5 for ‘adherence-content’, 4.0 for ‘adherence-delivery’ and 4.5 for ‘quality of delivery’. Mean scores for Family Fun nights were 3.7 for ‘adherence- content’, 3.6 for ‘adherence-delivery’ and 3.7 for ‘quality of delivery’. Fidelity for PTC was assessed on five dimensions (knowledge, structure, teaching, process, and overall development) by reliable, trained coders rating videotapes of the PTC sessions on a 1–9 Likert type scale that has demonstrated predictive validity (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 2011). Mean scores were in the adequate to good range (5–7).

Assessment Procedures

Written consent was obtained from parents in accordance with procedures approved by the IRB of the University of Minnesota. Study research assistants completed assessments in the family’s apartment. A parent was asked to be present together with the index child. Where more than one child in the family was within the target age group, separate assessment sessions were scheduled for parent(s) and each child. Each parent received a $50 gift card for completing each assessment. Teachers received surveys with instructions for completion; for each completed packet teachers received a $20 gift card. Teacher data were available for 81% of the sample at baseline, 80% at 12-months, and 74% at 24-months post baseline. Assessments were conducted following recruitment, prior to the start of the intervention, and at 12- and 24-months post baseline.

Measures

Control variables.

Child age, parent income, race/ethnicity, and education were assessed in the context of a structured interview administered to parents (mothers or other female caretakers) during baseline data collection. Child age was measured in years since birth and child gender was scored as “1” for boys and “2” for girls. Parent education was years of schooling completed. Parent income was annualized dollar amount from reported weekly, monthly, and annual income. Racial/ethnic status of children was identified by mothers and was assessed at baseline. Variables were entered as dummy coded contrasts in the multivariate models coded 1 for “yes” and 0 for “no” with European Americans as the comparison group. Because of the infrequent cases for racial and ethnic minorities other than African Americans, categories were collapsed to European American, African American, and other Minority for analyses.

Outcome variables.

Outcome variables included parenting and child measures.

Parenting self-efficacy.

The Parental Locus of Control scale (Campis, Lyman, & Prentice-Dunn, 1986) assesses parents’ perceptions of their parenting control and efficacy with their child(ren). Forty-seven items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). For this analyses, we used the 10-item parenting self-efficacy subscale ranging from 10 to 50 (other subscales assess child’s control of parent’s life, parental responsibility, parental control of child’s behavior, and parental belief in fate/chance). The parenting self-efficacy scale included items such as “what I do has little effect on my child’s behavior” and “no matter how hard a parent tries, some children will never learn to mind.” The scale was scored to reflect higher levels of parenting self-efficacy (α=.67). Evidence for internal consistency (α=.44-.79) and construct and discriminant validity (r=.00-.54) were reported by Campis et al. (1986).

Parenting practices.

Parenting practices were assessed using observational ratings of mother-child interaction during Family Interaction Tasks (FITs). Drawn from prior observational studies of parent-child relationships in middle childhood, and modified for families experiencing homeless, the FITs provide validated measures of parenting practices demonstrating convergent validity, external validity predictive of children’s developmental outcomes, and measures that are clinically sensitive to parent training intervention (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999; Gewirtz, DeGarmo, & Medhanie, 2011). The FITs in the present study lasted approximately 20 minutes. First, the dyad was asked to solve two 5-minute problem-solving tasks (Issue A and B) that required resolving current self-selected conflict issues. During the problem solving task parents and children are asked to each identify a topic to discuss. For the first 5 minutes they are instructed to talk about the problem that the parent picked (e.g., talking back and arguing with parents) and try to find a way to solve it. For the last 5 minutes they are instructed to discuss the issue that the child picked (e.g., doing homework) and try to figure out a way to solve it. Following this, mother and child engaged in three cooperation, competition and teaching tasks: a guessing game, labyrinth game, and tangoes task. At the end families were debriefed in order to address any concerns or questions.

FITs were videotaped and coded using previously validated ratings of key parenting practices predictive of children’s developmental outcomes (DeGarmo et al., 2004) including skill encouragement, positive involvement, problem solving outcome, and inept coercive discipline. Trained coders, blind to families’ assignment to study conditions, provided Likert-type ratings after directly viewing each of the respective interaction tasks, and overall global impressions were provided after viewing and scoring all of the tasks. To assess coder agreement, 24% of the videotaped sessions were randomly selected for reliability checks. For Likert type rating scales we computed the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) as an index of inter-rater reliability. Inept coercive discipline was an 11-item scale score rated on a 5-point scale; items included mother was… overly strict, authoritarian, erratic, inconsistent, oppressive, used nagging or nattering to get compliance, and so on. Cronbach’s α was .87. Coder ICC was .69.

Prosocial parenting was the mean of two positive parenting practice scales, parent’s skill encouragement and positive involvement. Skill encouragement was based on 9 items rating the mother’s ability to promote children’s skill development through contingent encouragement and scaffolding strategies observed during the labyrinth, guessing game, and tangoes tasks. Cronbach’s α was .78. Coder ICC was .54. Positive involvement was based on 31 items selected from the refreshment, tasks, clean up, problem solving, and game tasks. Cronbach’s α was .96. Coder ICC was .88. Problem solving outcome was assessed with a 9-item scale scored for each of the two problem solving discussions.

Items were rated on a 5-point scale indicating the solution quality, extent of resolution, apparent satisfaction, likelihood of follow through, etc. Cronbach’s α was .92 for Issue A and .93 for Issue B. Coder ICC was .79 and .67, respectively across Issues A and B.

Child adjustment.

Child adjustment was assessed with two standardized measures. The Behavior Assessment System for Children (2nd Ed.) – (BASC2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) is a multidimensional system used to assess broad domains of externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and adaptive skills (alphas = .84-.90).

Items are rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 = never to 3 = almost always. Age- and gender-specific normative scores are provided in the form of T-scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. T scales are preferred particularly for composite scales and are more likely to meet normality assumptions of growth analyses (Distefano & Kamphaus, 2008). The BASC-2 are specifically computed as linear transformations of the raw scores (see Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). Teacher (TRS) and parent rating scales (PRS) of the BASC2 were utilized in this study; moderate to good reliability and validity are reported (Reynolds & Camphaus, 2004). In this study we focused on the depression (TRS α = .84, PRS α = .88). and externalizing problem scales (TRS α = .90, PRS α = .86). We chose depression specifically as opposed to the broader dimension of internalizing because we wanted to specify and test a replication hypothesis based on prior findings of outcomes from the evaluation of the PTC intervention which demonstrated reductions in children’s depression and externalizing symptoms with samples of at-risk mothers (DeGarmo et al., 2004; Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999).

The Behavioral and Emotional Rating Scale: A Strength-Based Approach to Assessment (2nd Ed.) (BERS2; Epstein, 2004) is a standardized measure designed to assess the behavioral and emotional strengths of children. The strength index scale T scores from the teacher and parent rating forms (α = .90 and .84, respectively) were used in this study. Items are rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 = not at all like the student to 3=very much like the student.

Attrition analyses.

These were conducted comparing participants who were retained at Time 3 (66%) with the families who were lost to follow up (34%). Results indicated that no significant differences were observed for intervention condition, site, female caretaker’s age, annual income, education, child’s age, gender, ethnicity, initial severity of externalizing problems, and depression. The means and standard deviations for the child and parent outcomes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for Study Outcome Variables Across Time by Group Condition

| Control |

Intervention |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow Up 1 | Follow Up 2 | Baseline | Follow Up 1 | Follow Up 2 | |||||||

| Variables | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Parent Outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Observed Parenting | 2.72 | .65 | 3.19 | .68 | 3.16 | .47 | 2.88 | .60 | 3.20 | .58 | 3.09 | .55 |

| Poor Parental Self-efficacy | 34.28 | 5.59 | 34.35 | 5.03 | 34.23 | 4.82 | 33.25 | 5.09 | 33.92 | 5.87 | 34.64 | 4.32 |

| Child Outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Strengths-Parent report | 47.47 | 8.71 | 48.02 | 9.43 | 47.77 | 9.82 | 47.35 | 9.56 | 47.93 | 8.27 | 49.44 | 8.35 |

| Depression-Parent report | 58.83 | 14.35 | 58.03 | 14.99 | 60.25 | 15.54 | 58.13 | 11.43 | 55.35 | 10.18 | 52.61 | 9.09 |

| Strengths -Teacher report | 47.76 | 10.35 | 48.24 | 11.10 | 49.72 | 10.24 | 47.66 | 10.24 | 47.15 | 9.75 | 47.53 | 10.39 |

| Externalizing-Teacher report | 57.54 | 11.75 | 58.69 | 13.47 | 55.20 | 12.74 | 60.08 | 13.93 | 60.05 | 14.09 | 58.55 | 12.90 |

Analytic Strategy and Multilevel Framework

The present study was a clustered randomized control trial with randomization occurring at the housing site level. Parents and children are clustered or nested within sites, and children are nested within families. Further, repeated assessments over time were also nested within individual children. The analysis plan, then, required a four level analysis to account for non-independence of observations in the data with Level 1 repeated outcomes nested within children at Level 2, children nested within mothers at Level 3, and mothers nested within housing sites at Level 4. Ignoring clustering increases risk of Type 1 error and downward biasing standard errors (Clarke, 2008).

Specifically, hypotheses were tested with hierarchical linear growth models in HLM7 (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, Congdon, & du Tolt, 2011). HLM is a multilevel regression framework also known as mixed modeling. Growth modeling is a special case of multilevel modeling where the time-varying outcomes are repeated measures at Level 1 nested within individuals at Level 2. Time invariant variables such as baseline covariates and random assignment to intervention or control condition at the Level 4 housing site level, are entered as predictors of time-ordered growth rates at Level 1. HLM allows Level 1 missing data for estimates of growth rates; data must be non-missing for the time-invariant fixed effects covariates (e.g., gender, age at baseline, random assignment).

For the continuous level data for child outcomes and parent outcomes, model specification took the general form of the following, where child outcomes were parent reported strengths, parent reported depression, teacher reported strengths, and teacher reported externalizing; parent outcomes were parental efficacy and parenting practices.

where at Level 1, child outcome is a function of the baseline intercept ѱ0 for each child, a linear growth rate ѱ1 estimated over two years, plus a random error term ε. Time weighting was 0, 1, and 2, representing baseline intercepts and linear growth over two years (Biensanz et al., 2008). Focusing on Time as the growth rate for the dependent variable, after summarizing individual growth rates at Level 1, the Level 2 model then regresses growth slopes on child predictors as π11; Level 3 parent predictors as β101; and the Level 4 random assignment group contrast as γ1001 (ER Group Assignment).

Results

Parenting Outcomes

To evaluate hypotheses, we specified three-wave linear growth models as noted directly above. We entered variables in theoretical blocks, also known as hierarchical entry (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003) first entering the main effects of random assignment plus baseline control variables (Model 1). In the second block, for measures that were repeated over time such as parenting, we entered time-varying predictors of child outcomes (Model 2). Estimands for time-varying covariates are the average of synchronous time period effects controlling for other variables in the model, e.g., the average level of parenting over three waves (see Singer & Willett, 2003 for discussion of average effect of parenting over three time points). We also evaluated a third block of variables which were the “time-ordered” change slopes for predictors at level one, or the linear increases or decreases (Model 3). Analogous to the growth slope for the outcome, for example, the change scores are time weighted level one predictors (i.e., Δ change in parenting = time × time-varying parenting).

For child and parent outcomes, only average level time varying effects obtained significance, therefore, results are presented that focus on estimates from Models 1 and 2 only. Results for the parent outcomes are shown in Table 2. The intercept and time variables represent the covariate adjusted intercept levels and growth rates. Starting with Model 1, no main effect of the intervention was observed for changes in maternal parenting practices. However, mothers in the ER group increased in parenting self- efficacy at a greater rate than mothers in the comparison group (ѱ = .87, p <.05). In Model 2 we entered parenting self-efficacy as a predictor of parenting practices as we previously found support for maternal parenting as a mediator of parenting self-efficacy on child adjustment (Gewirtz et al., 2009). The time varying prediction model showed that parenting self-efficacy had a beneficial impact on parenting over time as expected (ѱ = .04, p <.001), and further, this effect was moderated or amplified by the intervention condition (ER group × parenting self-efficacy ѱ = .01, p <.05). That is, the beneficial impact of improved parenting self-efficacy was greater for the ER intervention group than the control condition. The proportion of explained variance (PVE) was .16 and .07 respectively for the parenting and parenting self-efficacy models, based on the residual variance of the models (PVE = unconditional residual variance minus the variance of the conditional or compositional model, divided by the unconditional variance). The effect size for the main effect of ER on parenting self-efficacy was a medium to large effect (ES = .79) calculated as the group mean differences in growth rates divided by the standard deviation of the growth rates in the unconditional model (Feingold, 2009).

Table 2.

Unstandardized HLM Estimands for 2 Year Growth Rates in Parent Outcomes

| Observed Parenting Practices |

Parenting Self Efficacy |

|

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||

| Intercept | 2.86*** | 33.69 |

| Time (growth rate) | 42*** | −.41 |

| Baseline Predictors | ||

| ER Group | −.04 | .87* |

| Age | −.01 | .07 |

| Boy | −.08 | −.40 |

| African American | −.14* | −.31 |

| Other Minority | −.05 | −.13 |

| Model 2 | ||

| Time Varying Predictors (average effects) | ||

| Parenting self-efficacy | .04*** | --- |

| ER Group × self-efficacy | .01* | --- |

| PVE | .16 | .07 |

Note: PVE = proportion of variance explained;

p < .001;

p < .001;

p < .05;

p <.10

Child Outcomes

We next tested for main effects of the intervention on child outcomes and whether changes in parenting practices and parenting self-efficacy were linked to growth in child outcomes. Results of the child outcome models are shown in Table 3. There was no main effect of the ER intervention on parent reported child strengths. However, Model 2 indicated that more effective observed parenting practices predicted higher reported child strengths (ѱ = 1.58, p <.01) and parenting self-efficacy predicted increases in strengths (ѱ = .20, p <.01). For example, for every one unit increase in observed parenting there were 1.58 unit increases on the BASC interpersonal strengths scale. A main effect of the intervention was observed for parent reported child depressive symptoms. Children in the ER group had greater reductions in depressive symptoms relative to their control counterparts (ѱ = −2.13, p <.01). The covariate adjusted growth rate also indicated that the sample was reported to increase in depression over time. Parenting efficacy had a marginal beneficial effect on depressive symptoms (ѱ = −.16, p <.10).

Table 3.

Unstandardized HLM Estimands for Predictors of 2 Year Growth Rates for Child Outcomes

| Strengths Parent Report |

Depression Parent Report |

Strengths Teacher Report |

Externalizing Teacher Report |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||||

| Intercept | 35.67*** | 64.21*** | 42 77*** | 64.18*** |

| Time (growth rate) | −0.77 | 4.91** | −0.66 | 1.89 |

| Baseline Predictors | ||||

| ER Group | −0.06 | −2.13** | −1.58 | 2.38 |

| Age | 0.02 | −0.35* | −0.00 | −0.03 |

| Boy | −0.06 | −1.12 | 0.85 | −1.96 |

| Black | 1.47† | −2.98** | 1.57 | −2.35 |

| Other Minority | −0.63 | −1.52 | 2.24 | −3.17 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Level 1 Time Varying Predictors | ||||

| Observed Parenting | 1.58** | −0.06 | 2.11* | −2.30* |

| Parenting Efficacy | 0.20** | −0.16† | −0.05 | 0.07 |

| PVE | .10 | .14 | .05 | .07 |

Note: PVE = proportion of variance explained;

p < .001;

p < .001;

p < .05;

p <.10

For teacher reported variables, no main effects of the intervention were observed. However, over time, maternal parenting practices predicted teacher reported strengths (ѱ = 2.11, p <.05) and externalizing (ѱ = −2.30, p <.05) in the expected direction. No independent effects of parenting self-efficacy were found for teacher reported outcomes.

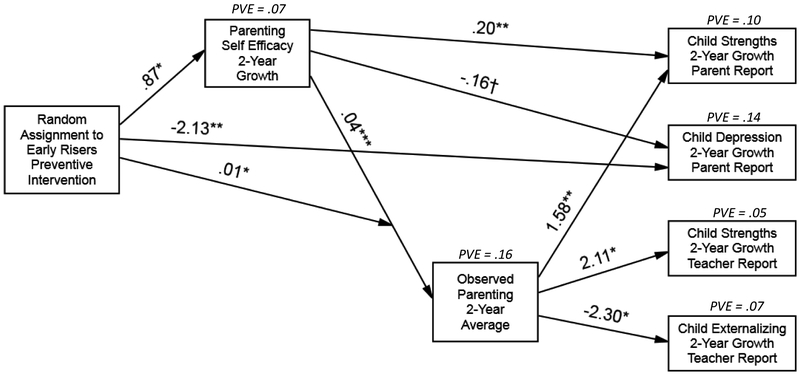

Overall, the predictive models explained 10 and 14 percent of the variance respectively in parent reported strengths and depression, and explained 5 and 7 percent respectively in teacher reported strengths and externalizing. In summary, there was a main effect of the ER intervention on parenting self-efficacy, and self-efficacy was linked to observed parenting. Without a direct effect of the intervention on parenting, full mediational analyses were precluded (cf. Gewirtz et al., 2009), or what Xao, Lynch, & Chen characterize as complimentary mediation. Thus, we proceeded to test for indirect effects (or indirect mediation, Xao et al., 2010). Support was obtained for the 4–1-1 cross- level indirect effect of the ER program on parenting through parental efficacy (indirect effect = .036, SE = .017, t = 2.14, p <.04). As a time-varying predictor, observed parenting in turn was linked to three of the four child outcomes reported by parents and teachers. Only one main effect was observed for child outcomes, parent report of depression symptoms, with the data indicating that the sample as a whole was at risk for growth in depression. The effect size for the main effect of the ER program on parent reported depression was large (ES = 1.2). To illustrate effects of the Early Risers preventive intervention program and relations among study variables, a summary of the study findings illustrating the unstandardized four-level model-based effects is displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Heuristic summary of statistically significant study findings illustrating the unstandardized four-level model-based effects for the Early Risers preventive intervention and relations among study outcomes. Parameters are from HLM tables in text. PVE = proportion of variance explained; ***p < .001; **p < .001; *p < .05; †p <.10.

Discussion

Results from this intent-to-treat analysis of the Early Risers program in supportive housing indicate that the intervention had direct and indirect effects on the putative outcomes. Parents assigned to the Early Risers condition showed significant improvements in parenting self-efficacy over time compared with parents in the control sites. This is particularly important because the circumstances of family homelessness (e.g., extreme poverty, lack of a capacity to meet children’s basic needs, child welfare involvement) provide fertile ground for extreme disempowerment and low self-efficacy in parenting. ER family advocates reported that helping formerly homeless mothers to gain confidence in their ability to parent was a key project goal, and they accomplished this by teaching mothers how to access resources and supports and coaching them in effective communication and problem-solving. Our findings resonate with the recommendations of Thompson, Kaslow, Short, & Wyckoff (2002) from their study of abused African American women - that interventions to improve self-efficacy should help women access social network support and material resources. Indeed, Matlin, Molock & Tebes (2011) demonstrated the crucial role of family and peer support in reducing suicidality risk and moderating links between depression and suicidality among African American youth.

Consistent with earlier research (Elder et al., 1995; Gewirtz et al., 2009) growth in parenting self-efficacy predicted more effective observed parenting practices. That is, mothers with higher parenting self-efficacy were observed – on average - to be more effective at family-problem solving, contingent discipline, warmth, and encouragement.

We found no main effects of the intervention on parenting practices, and we speculate that this may be related to the timing of the parenting intervention. PTC (the most intensive parenting element of ER) was provided only in the program’s second year (ending several months prior to the two year assessment). In an efficacy trial of PTC, intervention effects on observed parenting practices were found beginning 6 months post- intervention, but these effects grew over time (Forgatch, Patterson, & DeGarmo, 2009).

Over time, improvements in parenting self-efficacy as a result of the intervention were associated with more effective observed parenting practices. In our study, testing the effect of parenting as a time varying predictor of parental efficacy also obtained a significant association (model not shown); and therefore, there is likely a reciprocal and mutually reinforcing relation among the constructs of parenting self-efficacy and parenting practices. That is, as mothers feel more self-efficacy in the parenting role, they demonstrate more effective parenting, which, in turn, helps them feel better at parenting. A similar such process was documented for changes in maternal depression and effective parenting practices for a single mother sample in the original randomized trial of the PTC program (Patterson, DeGarmo, & Forgatch, 2004).

In turn, stronger observed effective parenting practices were associated with better teacher- and parent-reports of child adjustment in three of the four child adjustment indices (teacher report of child externalizing, and both teacher and parent report of child strengths). Prior ER studies have demonstrated that self-reported parenting practices (discipline in particular) mediated long-term improvements in child conduct problems (Bernat, August, Hektner, & Bloomquist, 2007). However, this is the first ER study to strengthen measurement by including observational measures of parenting.

Our findings suggest that, in this population of homeless families, the ER intervention may provide a catalyst for change that impacts the family system over time, by empowering parents to have greater confidence in their capacity to parent effectively, which then is associated with improvements in parenting practices, and child adjustment.

The ER intervention had a direct or main effect on parent reports of child depression such that assignment to the Early Risers condition was associated with significant reductions in parent report of child depression symptoms over the 2 years. This finding occurred despite an overall increase in depression symptoms in the sample over the same time period, which is unsurprising given the stress associated with high mobility and extreme poverty in this population of families and consistent with data revealing high rates of depressive symptoms in homeless children and parents (Bassuk et al., 1998). The extremely adverse context and overall depression trend highlights the salience of our main effect finding of reduced child depressive symptoms in the ER condition. One reason for this finding might be that the child-focused elements of the ER intervention (i.e. the PATHS after-school and summer camp programs) specifically target socio-emotional functioning in children. For example, children are taught to identify, label and regulate their own emotions, and address dysfunctional cognitions. In parallel to our findings regarding parenting self-efficacy in mothers, it is possible that the most proximal effect of the intervention overall was to boost positive cognitions and emotions in parents and children – reflected in the reductions in child depressive symptoms and the improvements in parenting efficacy in their mothers. We acknowledge, however, that these analyses rely on maternal, rather than child self-report. It is possible that a social desirability bias led intervention group mothers to under-report children’s depression.

At two years post-baseline, the ER intervention did not have direct effects on other indices of child adjustment (i.e. conduct problems or strengths). However, subsequent analyses at three years post-baseline indicated main effects of the intervention on child conduct problems (Piehler, August, Bloomquist, Gewirtz, Lee, & Lee, 2013).

Moreover, our results are congruent with the results of the original PTC efficacy study with single mothers, which showed that reductions in child depression preceded reductions in child behavior problems (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999) for those in the intervention group. Prior ER findings indicated reductions in child oppositional-defiant problems lasting over 6 years following intervention (August et al., 2001; Bernat et al., 2007), particularly among youth with higher baseline conduct problems. The trajectories of change in child behavior may differ between populations (i.e. homeless vs. housed populations in prior studies) particularly because of the greater prevalence of depression in homeless populations. An earlier study comparing these families with families in an earlier ER trial of primarily inner-city youth with conduct problems demonstrated that the current sample had comparable levels of conduct problems to that group, but that parents in this sample showed far higher levels of mental health problems; Lee et al., 2010).

Several limitations of the study should be highlighted. First, as noted earlier, we relied on parents’ report of their children’s depressive symptoms, which may be inferior to children’s own reports, partly because internal states are likely best reported on by the individual experiencing them, and partly because maternal reports may have been more subject to desirability bias, as noted earlier. Second, our parent sample was overwhelmingly female-headed and single, so our results cannot be generalized to two parent or male-headed homeless families. Prevention studies with the highest risk populations often are beset with challenges; our high attrition rates (22% at 1-year follow-up and 34% at 2-year follow up) attest to this. Recruiting more than one child per family enabled us to increase sample size and therefore power to detect effects; this also reflected the reality of the prevention program service delivery, which included all children in the family. The analytic method (HLM7) enabled examination of the interrelationships between outcome variables while simultaneously accounting for the multiple levels of clustering in this study; i.e., more than one participating child per family, multiple families within housing site, time, and intervention/control.

Our findings suggest that family supportive housing may provide a special opportunity to promote child adjustment in an extremely high-risk population. The ER intervention directly enhanced family members’ feelings about themselves and their efficacy, suggesting that improving feelings of worth and effectiveness in homeless parents and their children may be an important first step in improving other indices of adjustment. Empowering homeless mothers might optimally include explicit strategies to improve their confidence in their own capacities to parent; instilling a sense of efficacy in parenting may be key to improving parenting practices For children, social cognitive and social learning prevention strategies may be key to reducing depressive symptoms.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide findings from a randomized controlled trial of a prevention program targeting parenting and child adjustment in supportive housing. Moreover, this homeless sample was largely African American and multiracial, extending the generalizability of our findings to a more heterogeneous minority population. African American mothers are overrepresented among homeless families, even controlling for poverty status, yet few prevention programs have successfully reached them. Recent longitudinal data (Fothergill, Doherty, Robertson, & Ensminger, 2012) suggests that family-related risk factors (teen parenting, violence, poor conduct, adolescent substance use) predict subsequent homelessness in African-Americans. Moreover, compared with European American families, parenting practices are stronger protective factors against conduct and substance use risk behaviors in African American families (Wallace et al. 2002). Given that, family-based prevention programs targeting parenting may be especially important for this population.

Further research should use data from parents and their children, particularly on ratings of depressive symptoms. Tests of other family-focused prevention programs will reveal whether our findings (of proximal change in affective and cognitive variables prior to behavior changes) are unique to this study, or more typical in this highly stressed population. The results from this trial reflect both the benefits and the challenges of conducting prevention research with extremely high-risk families. Despite significant logistical and methodological challenges, the data suggest that the ER program appears to have provided psychosocial benefits to formerly homeless children and their parents.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant MH074610–01 from the Child and Adolescent Preventive Intervention Program, NIMH, and in part by Grant P30 DA023920, Division of Epidemiology, Services and Prevention Branch, NIDA. We acknowledge with gratitude the 16 agencies comprising the Healthy Families Provider Network, as well as Hart-Shegos and Associates, the Family Supportive Housing Center, LLC, and the Family Housing Fund. Their partnership and work to support formerly homeless children and families has been invaluable. In particular, we are grateful to all the families who participated in this Early Risers prevention trial.

Footnotes

Although a partner in the provider group of the family supportive housing agencies, this specific site functions more as an extended-stay shelter rather than a formal transitional or permanent supportive housing program. As such, they provide bedrooms to clients rather than apartments.

Contributor Information

Abigail H. Gewirtz, Department of Family Social Science & Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota.

David S. DeGarmo, University of Oregon & Oregon Social Learning Center

Susanne Lee, Department of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota

Nicole Morrell, Department of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota

Gerald August, Departments of Family Social Science & Psychiatry, University of Minnesota

References

- Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, El-bourne D, . . . the CONSORT GROUP (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). (2001). The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 134, 663–694. 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anooshian LJ (2005). Violence and aggression in the lives of homeless children. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10, 129–152. 10.1016/j.avb.2003.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, Bloomquist ML, Lee SS, Realmuto GM, & Hektner JM (2006). Can evidence-based prevention programs be sustained in community practice settings? The Early Risers’ Advanced-Stage Effectiveness Trial. Prevention Science, 7, 151–165. 10.1007/s11121-005-0024-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, Realmuto GM, Hektner JM, & Bloomquist ML (2001). An integrated components preventive intervention for aggressive elementary school children: The early risers program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 614–626. 10.1037/0022-006X.69.4.614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk EL, Buckner JC, Perloff JN, & Bassuk SS (1998). Prevalence of mental health and substance use disorders among homeless and low-income housed mothers. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 1561–1564. 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk EL, Weinreb LF, Dawson R, Perloff JN, & Buckner JC (1997). Determinants of behavior in homeless and low-income housed preschool children. Pediatrics, 100, 92–100. 10.1542/peds.100.1.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat DH, August GJ, Hektner JM, & Bloomquist ML (2007). The Early Risers preventive intervention: Testing for six-year outcomes and mediational processes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 605–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesanz JC, Deeb-Sossa N, Papadakis AA, Bollen KA, & Curran PJ (2004). The role of coding time in estimating and interpreting growth curve models. Psychological Methods, 9, 30–52. 10.1037/1082-989X.9.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campis LK, Lyman RD, & Prentice-Dunn S (1986). The parental locus of control scale. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 15, 260–267. 10.1207/s15374424jccp1503_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P (2008). When can group level clustering be ignored? Multilevel models versus single-level models with sparse data. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 62, 752–758. 10.1136/jech.2007.060798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, & Aiken L (2003). Applied multiple regression correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, & Brody GH (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38, 179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Patterson GR, & Forgatch MS (2004). How do outcomes in a specified parent training intervention maintain or wane over time? Prevention Science, 5, 73–89. 10.1023/B:PREV.0000023078.30191.e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano C, & Kamphaus RW (2008). Latent growth curve modeling of child behavior in elementary school. Research in the Schools, 15, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Wheeler LA, & Millsap RE (2010). Parenting self-efficacy and parenting practices over time in Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 522–531. doi: 10.1037/a0020833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GHJ, Eccles JS, Ardelt M, & Lord S (1995). Inner-city parents under economic pressure. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 57, 771–784. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein MH (2004). BERS-2: Behavioural and Emotional Rating Scale (2nd ed.) Examiner’s manual. Austin, TX: ProEd. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A (2009). Effect sizes for growth-modeling analysis for controlled clinical trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychological Methods, 14, 43–53. 10.1037/a0014699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, & DeGarmo DS (1999). Parenting through change: An effective prevention program for single mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 711–724. 10.1037/0022-006X.67.5.711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Knutson N, Rains L, & Sigmarsdottir M (2011). Fidelity of implementation rating system: The manual for PMTO. Eugene, OR: ISII. [Google Scholar]

- Fothergill KE, Doherty EE, Robertson JA, & Ensminger ME (2012). A prospective study of childhood and adolescent antecedents of homelessness among a community population of African Americans. Journal of Urban Health, 89, 432–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH (2007). Promoting children’s mental health in family supportive housing: A community-university partnership for formerly homeless children and families. Journal of Primary Prevention, 28, 359–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, & August GJ (2008). Incorporating multifaceted mental health prevention services in community sectors-of-care. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11, 1–11. 10.1007/s10567-007-0029-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, Burkhart K, Loehman J, & Haukebo B (2014). Research on programs designed to support positive parenting In Haskett ME, Perlman S, & Cowan BA (Eds.), Supporting families experiencing homelessness: Current practices and future directions (pp. 173–186). New York, NY: Springer Press; 10.1007/978-1-4614-8718-0_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, Degarmo DS, & Medhanie A (2011). Effects of mother’s parenting practices on child internalizing trajectories following partner violence. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 29–38. 10.1037/a0022195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz A, DeGarmo D, Plowman E, August G, & Realmuto G (2009). Parenting, parental mental health, and child functioning in families residing in supportive housing. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79, 336–347. 10.1037/a0016732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, Hart-Shegos E, & Medhanie A (2008). Psychosocial status of children and youth in supportive housing. American Behavioral Scientist, 51, 810–823. 10.1177/0002764207311989 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz A, & Taylor T (2009). Participation of homeless and abused women in a parent training program In Hindsworth MF & Lang TB (Eds.), Community participation and empowerment (pp. 97–114). Hauppage, NY: Nova. [Google Scholar]

- Herbers JE, & Cutuli JJ (2014). Programs for homeless children and youth: A critical review of evidence In Haskett ME, Perlman S, & Cowan BA (Eds.), Supporting families experiencing homelessness: Current practices and future directions (pp. 187–207). New York, NY: Springer Press; 10.1007/978-1-4614-8718-0_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- HUD. (2010). The 2010 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress iii (2010), http://www.hudhre.info/documents/2010HomelessAssessmentReport.pdf

- HUD. (2013). The 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Washington, DC: US Department of Housing and Urban Development; https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/ahar-2013-part1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jones TL, & Prinz RJ (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25, 341–363. 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer RP, Cook JR, Crusto C, Strater KP, & Haber MG (2012). Understanding the ecology and development of children and families experiencing homelessness: Implications for practice, supportive services, and policy. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82, 389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblinsky SA, Morgan KM, & Anderson EA (1997). African-American homeless and low-income housed mothers: Comparison of parenting practices. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 67, 37–47. 10.1037/h0080209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusche CA, & Greenberg MT (1993). The PATHS (Promoting alternative thinking strategies) curriculum. Deerfield, MA: Channing-Bete Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, August GJ, Realmuto GM, Horowitz JW, Bloomquist ML, & Klimes-Dougan B (2008). Fidelity at a distance: Assessing implementation fidelity of the Early Risers Prevention Program in a going-to-scale intervention trial. Prevention Science, 9, 215–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, August GJ, Gewirtz AH, Klimes-Dougan B, Bloomquist ML, & Realmuto GM (2010). Identifying unmet mental health needs in children of formerly homeless mothers living in a supportive housing community sector of care. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 421–432. 10.1007/s10802-009-9378-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Hubbard JJ, Gest SD, Tellegen A, Garmezy N, & Ramirez M (1999). Competence in the context of adversity. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 143–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlin SL, Molock SD, & Tebes JK (2011). Suicidality and depression among African American adolescents: The role of family and peer support and community connectedness. American journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81, 108–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent anti-social behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701. 10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR (1982). Coercive family process (Vol. 3). Eugene, OR: Castalia Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, & Ramsey E (1989). A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist, 44, 329–335. 10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Forgatch MS, & DeGarmo DS (2010). Cascading effects following intervention. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman S, Cowan B, Gewirtz A, Haskett M, & Stokes L (2012). Promoting positive parenting in the context of homelessness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82, 402–412. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01158.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piehler TF, Bloomquist M, August GJ, Gewirtz AH, Lee S, & Lee W (2014). Executive functioning as a mediator of conduct problems prevention in children of homeless families residing in temporary supportive housing. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 681–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong Y, Congdon J, & Tolt M (2011). HLM7: Hierarchical linear & nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: SSI, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, & Kamphaus RW (2004). Behavior assessment system for children (2nd ed.). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M, Rog DJ, & Culhane DP (2006). Family homelessness: Background research findings and policy options. Washington, DC: Interagency Council on Homelessness. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, McGuinn L, . . . Wood DL (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129, e232–e246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, & Willett JB (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195152968.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strayhorn JM, & Weidman CS (1988). A parent practices scale and its relation to parent and child mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(5), 613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Kaslow NJ, Short LM, & Wyckoff S (2002). The mediating roles of perceived social support and resources in the self-efficacy-suicide attempts relation among African American abused women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 942–949. 10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE, & Smith RS (1992). Overcoming the odds: High risk children from birth to adulthood. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Lynch JG, & Chen Q (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 197–206. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/651257 [Google Scholar]