Abstract

The study demonstrates protein tyrosine nitration as a functional post-translational modification (PTM) in biology and pathobiology of the oomycete Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary, the most harmful pathogen of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Using two P. infestans isolates differing in their virulence toward potato cv. Sarpo Mira we found that the pathogen generates reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in hyphae and mature sporangia growing under in vitro and in planta conditions. However, acceleration of peroxynitrite formation and elevation of the nitrated protein pool within pathogen structures were observed mainly during the avr P. infestans MP 946-potato interaction. Importantly, the nitroproteome profiles varied for the pathogen virulence pattern and comparative analysis revealed that vr MP 977 P. infestans represented a much more diverse quality spectrum of nitrated proteins. Abundance profiles of nitrated proteins that were up- or downregulated were substantially different also between the analyzed growth phases. Briefly, in planta growth of avr and vr P. infestans was accompanied by exclusive nitration of proteins involved in energy metabolism, signal transduction and pathogenesis. Importantly, the P. infestans-potato interaction indicated cytosolic RXLRs and Crinklers effectors as potential sensors of RNS. Taken together, we explored the first plant pathogen nitroproteome. The results present new insights into RNS metabolism in P. infestans indicating protein nitration as an integral part of pathogen biology, dynamically modified during its offensive strategy. Thus, the nitroproteome should be considered as a flexible element of the oomycete developmental and adaptive mechanism to different micro-environments, including host cells.

Keywords: protein tyrosine nitration, peroxynitrite, reactive nitrogen species, pathogen offensive strategy, Phytophthora infestans, potato, late blight

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is a crucial signaling molecule during both the highly conserved pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) triggered immunity (PTI) and in a highly specific effector-triggered immunity (ETI) (e.g., Asai and Yoshioka, 2009; Perchepied et al., 2010; Bellin et al., 2013; Schlicht and Kombrink, 2013). Although NO is neither a strong oxidant nor a strong reductant (Bartesaghi and Radi, 2018), the NO burst occurring at the site of attempted host colonization may effectively stimulate a further sequence of defense events (Arasimowicz-Jelonek and Floryszak-Wieczorek, 2011; Vandelle and Delledonne, 2011). It is well established that the signaling mode of NO action at the molecular level involves post-translational modification (PTM) of proteins including protein tyrosine (Tyr) residue nitration via the NO-derived molecule - peroxynitrite (ONOO-). Although this reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and ONOO--dependent protein nitration were first identified in animals as toxic events contributing to oxidative and nitrosative stress in the biological milieu, there is increasing evidence that Tyr nitration is a selective process with a well-defined target (Radi, 2013). According to Bartesaghi et al. (2007) nitro-Tyr yield is low under physiological conditions and only 1–5 nitro-Tyr residues per 10,000 tyrosines is detectable. It has also been shown that the phenomenon is dependent on the protein composition, structure, its intracellular concentration, localization and interaction with other molecules (Abello et al., 2009). This PTM affects the activity, stability or the intracellular location of proteins, thus potentially altering their functions and signal transduction (Greenacre and Ischiropoulos, 2001). It has been experimentally confirmed that nitration of critical Tyr residues may lead to both activating and suppressing of protein function (e.g., Ji et al., 2006; Chaki et al., 2009b; Begara-Morales et al., 2015; Yeo et al., 2015). Interestingly, some data showed that the selective nitration of Tyr residues via ONOO- may also interfere with signaling processes associated with protein Tyr phosphorylation (Monteiro et al., 2008; Aburima et al., 2010).

Importantly, generation and potential functions of NO during biotic interactions have so far been analyzed solely from the point of view of the host plant. However, too often the role of NO within the pathogen is ignored when considering plant-pathogen interactions (Mur et al., 2006; Arasimowicz-Jelonek and Floryszak-Wieczorek, 2014, 2016). Recent advances in understanding of plant-pathogen systems have shown that plant pathogens are also capable of NO synthesis and might employ NO to colonize the host (Turrion-Gomez and Benito, 2011; Samalova et al., 2013). Unfortunately, the functional role of RNS in this systematically heterogeneous group of microorganisms has not been thoroughly studied to date. However, eukaryotic plant pathogens belonging to Fungi and fungus-like Oomycetes, potentially cope with various NO biosynthetic and NO detoxification routes (Arasimowicz-Jelonek and Floryszak-Wieczorek, 2016). For example, NO generation has been detected in mycelia of Blumeria graminis (Prats et al., 2008), Oidium neolycopersici (Piterková et al., 2011), Magnaporthe oryzae (Samalova et al., 2013) and in hyphae and infection structures of the oomycete Bremia lactucae (Sedlárová et al., 2011). Although, precise mechanism of NO-mediated regulation in plant pathogens has not been yet clarified, experimental data revealed NO participation during pathogen development, virulence and its survival in the host (Arasimowicz-Jelonek and Floryszak-Wieczorek, 2014, 2016). Since protein nitration is a universal mechanism of intracellular signaling found in organisms belonging to distinct systematic groups, it may be suspected that similarly, to mammals and plants Tyr nitration might greatly affect protein function also in filamentous plant pathogens, such as e.g., fungi and oomycetes. In confirmation, the first and to date the only report revealed the presence of nitrated proteins in the crude extract of the sunflower downy mildew oomycete Plasmopara halstedii, however, the identification and potential relevance of this PTM in the pathogen biology remains unexplored (Chaki et al., 2009a).

The oomycete Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary is a causative agent of late blight disease responsible for the great Irish famine in the mid-nineteenth century. Currently, late blight is considered as the most devastating disease of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.), generating costs of up to one billion euro per year in the EU alone (Resjö et al., 2017). In turn, potato is the largest non-cereal food crop worldwide and the fourth most important food crop after rice, wheat and maize with 300 million tons of annual global production (Raymundo et al., 2018). Thus, the pathogen is regarded as a threat to global food security. Although P. infestans has been studied for more than a century, progress made on disease control of host crops is still unsatisfactory, in part due to the fast evolution and adaptive capacity of the pathogen to new micro-environments (Forbes, 2012).

Since environmental adaptation of pathogens could be achieved at the molecular level through PTM of proteins, knowledge of NO-dependent PTM in biology and pathobiology of hemibiotrophic P. infestans seems to be essential. In the present study we characterized the NO metabolic status defined as the nitroproteome pattern during in vivo and in planta P. infestans hyphal growth conditions. An experimental approach involved avirulent (avr) and virulent (vr) P. infestans isolates (in reference to the potato genotype ‘Sarpo Mira’), creating a useful background for the identification of candidates of protein nitration, favorable host colonization.

Materials and Methods

Pathogen Culture

Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary – the avirulent isolate MP 946 (race 1.3.4.7.10.11) and the virulent MP 977 (race 1.2.3.4.6.7.10) in reference to the potato cv. Sarpo Mira, was provided by the Plant Breeding Acclimatization Institute (IHAR), Research Division in Młochów, Poland. For in vitro studies: the oomycete was grown for 9 days in the dark on a cereal-potato medium supplemented with dextrose. For in planta studies: potato plants were inoculated by spraying with 3 ml of a freshly prepared suspension of sporangia and zoospores (5.0 × 105 sporangia per ml) and incubated in a sterile boxes for 9 days at 16°C and 95% relative humidity in the darkness (sporangia of P. infestans were obtained by washing 14-day-old cultures with cold distilled water and zoospores were released by incubating the sporangia in water at 4°C for 2 h). The area under disease progress was evaluated on potato leaves 9 days after inoculation using a scale from I to IV (James, 1971), which represented the percentage of leaf area covered by late blight symptoms (I = 1 to 9%; II = 10 to 24%; III = 25 to 49%; IV = 50 to 100%; Supplementary Figure S1).

The hyphae growing in vitro or in planta were manually collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. Additionally, hyphae in planta were isolated by dipping the infected leaf in 5% cellulose acetate (dissolved in acetone), letting the acetone evaporate, and stripping the cellulose acetate film off the leaves according to Both et al. (2005).

Plant Material

Plants of the tetraploid potato cv. Sarpo Mira came from the Potato Gene bank (Plant Breeding and Acclimatization Institute – IHAR-PIB in Bonin, Poland). Potato seedlings propagated through in vitro culture were transferred to the soil (a composition of high peat moss approx. 50% in the substrate) and kept in a phytochamber with 16 h of light (180 μmol⋅m-2⋅s-1) at 18 ± 2°C and 60% humidity up to the stage of ten leaves.

Nitric Oxide and Peroxynitrite Detection

Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite formation was measured quantitatively using Cu-FL (2-{2-chloro-6-hydroxy-5-[2-methylquinolin-8-ylamino)methyl]-3-oxo-3H-xanthen-9-y1}benzoic acid, Strem Chemicals) and APF (aminophenyl fluorescein, Sigma), respectively. Pathogen samples (0.1 g) were incubated in the dark for 1 h in a mixture containing 10 μM Cu-FL in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.2) or 5 μM APF in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). After the incubation, the probes were transferred into 24-well plates (1 ml per well). Fluorescence in the reaction was measured using spectrofluorometer (Fluorescence Spectrometer Perkin Elmer LS50B, United Kingdom) at 488 nm excitation and 516 nm emission (for NO detection) and 490 nm excitation and 510 nm emission (for ONOO- detection) filters. Fluorescence was expressed as relative fluorescence units. Additionally, 1 mM cPTIO or 50 μM ebselen were used to scavenge NO and ONOO-, respectively.

Reactive Nitrogen Species Detection by Fluorescence Microscopy

Nitric oxide formation was detected using a fluorescent DAF-2DA dye (Calbiochem), while ONOO- production was localized using the fluorescent reagent aminophenyl fluorescein, APF (Sigma). Phytophthora infestans isolates were incubated with 10 mM DAF-2DA or 10 mM APF, prepared in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) for 1 h at room temperature. Additionally, 1 mM cPTIO or 50 μM ebselen were used to scavenge NO and ONOO-, respectively. After incubation, samples were washed several times in the same buffer and immediately examined under a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using standard filters and collection modalities for DAF-2DA (excitation 495 nm; emission 515 nm) and APF (excitation 490 nm; emission 515 nm) green fluorescence. Images were processed and analyzed using an LSM Image Browser (Zeiss).

Peroxynitrite Generator and Scavenger Treatment

To evaluate the effect of exogenous ONOO-, P. infestans hyphae were sprayed with ONOO- generator (50 μM 3-Morpholinosydnonimine, SIN-1, Calbiochem), which gradually decomposed to yield equimolar amounts of NO and O2-. Scavenger of ONOO- (50 μM ebselen, Sigma) were used to estimate the effect of endogenous ONOO- on protein Tyr nitration. Control cultures were treated with sterile water. After 24 h of hyphae incubation protein 3-nitrotyrosine assay was performed.

Protein 3-Nitrotyrosine Assay

Pathogen samples (0.2 g) were ground in liquid nitrogen to a fine powder, suspended in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.6) with 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT and 1 mM PMSF and centrifuged at 10 000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The protein concentration in the supernatant was determined with the Bradford (1976) assay, using BSA as the standard. 3-nitrotyrosine in a protein sample was measured using the OxiSelectTM Nitrotyrosine ELISA Kit (Cell Biolabs Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Protein Extraction, 2D Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blotting

Protein extraction for 2D electrophoresis was carried out according to Méchin et al. (2007). Briefly, pathogen samples (0.5 g) were ground in liquid nitrogen to a fine powder and proteins were precipitated with a cold TCA-acetone solution with the addition of 2-mercaptoethanol (0.07%) for minimum 1 h at -20°C. The proteins were then solubilized using DeStreak Rehydration Solution (GE HealthCare) supplemented with 20 mM DTT and 0.2% Bio-Lyte buffer (Bio-Rad). The concentration of proteins in the final samples was evaluated with the use of a commercial 2-D Quant Kit (GE Healthcare), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Approximately 100 μg of proteins were loaded onto 7 cm IPG strips with 3–10 pH gradients (Bio-Rad). The strips were rehydrated overnight and used for isoelectrofocusing (IEF) using a Protean IEF cell system (Bio-Rad). The run was carried out in the following order: (i) 300 V (1 h), (ii) 3500 V (1.5 h), and (iii) 3500 V (total 20,000 Vh). For the SDS-PAGE, the strips were equilibrated 2 times for 15 min in an equilibration buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.8, 6 M urea, 30% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.002% Bromophenol blue), first containing 65 mM DTT, followed by an equilibration buffer with 135 mM iodoacetamide. For separation in the second dimension the strips were applied to 10% precast polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad) and run in a Mini-PROTEAN Tetra Cell (Bio-Rad) at a constant current (20 mA per gel) with a Prestained Protein Ladder (Thermo Scientific). For Western blot analyses, proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes. After transfer, membranes were used for cross-reactivity assays with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against nitrotyrosine (Life Technologies, 1:1000 dilutions). To check the specificity of the anti-nitrotyrosine antibodies, sodium dithionite solution was used to reduce nitrotyrosine to aminotyrosine (Supplementary Figure S2). Briefly, the control PVDF membrane was incubated with solution of 10 mM sodium dithionite in 50 mM pyridine-acetate buffer (pH 5.0) for 1 h at room temperature. After the reaction, the membrane was equilibrated with 0.2% v/v Tween-20 in Tris–buffered saline and then incubated with anti-nitrotyrosine antibody as described above. For immunodetection the goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Agrisera) and Lumi-Light western blotting substrate (Roche) was used. At least three independent blots from different experiments were analyzed. The intensity of spots was quantified using a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad) coupled with a high-resolution camera, and protein spot intensity was analyzed by means of the MultiGauge (release 2.2) Fuji software. The quantitative results of protein Tyr nitration were calculated using MultiGauge software (Fuji) by summing the pixels intensity within each protein spot image, and the data were presented in comparison to the control sample average of 0 (control – in vitro growth of P. infestans).

Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Protein Identification

Protein identification was performed using liquid chromatography coupled to the mass spectrometer at the Laboratory of Mass Spectrometry, Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences (Warsaw, Poland). Protein spots were carefully cut out from the PVDF membranes manually under a binocular microscope using a sterile, disposable razor blade and subjected to the standard procedure of trypsin digestion as described earlier (Arasimowicz-Jelonek et al., 2016). Briefly, a concentrated and desalted peptide solution was separated on a nano-Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography RP-C18 column (Waters, BEH130 C18 column, 75 mm i.d., 250 mm long) of a nanoACQUITY UPLC system, using a 45 min linear acetonitrile gradient. Column outlet was directly coupled to the electrospray ionization (ESI) ion source of the Orbitrap Velos type mass spectrometer (Thermo), working in the regime of data dependent MS to MS/MS switch with the HCD type peptide fragmentation. An electrospray voltage of 1.5 kV was used. Raw data were pre-processed with the Mascot Distiller software (v. 2.4.2.0; Matrix Science), then obtained peptide masses and fragmentation spectra were matched to the Phytophthora UniProt database (18,581 sequences; 7,696,749 residues) using the Mascot search engine (Mascot Daemon v. 2.4.0, Mascot Server v. 2.4.1, and Matrix Science). The following parameters were adopted for database searches: enzyme specificity was set to semiTrypsin, peptide mass tolerance to 20 ppm and fragment mass tolerance to 0.1 Da. The protein mass was left as unrestricted, and mass values as monoisotopic with one missed cleavages being allowed. Alkylation of cysteine by carbamidomethylation was fixed and oxidation of methionine and carboxymethylation on lysine were set as a variable modification. Protein identification was performed using the Mascot search engine, with the probability-based algorithm. The expected value threshold of 0.05 was used for analysis, which means that all peptide identifications had less than a 1 in 20 chance of being a random match.

Statistical Analysis

All results are based on three biological replicates derived from three independent experiments. For each experiment, means of the obtained values (n = 9) were calculated along with standard deviations. To estimate the statistical significance between means, the data were analyzed with the use of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Dunnett’s test at the level of significance α = 0.05 or α = 0.01. The differences between protein spots in both P. infestans growth phases were determined using ANOVA followed by a student t-test with p < 0.05 as the limit of significance.

Results and Discussion

Reactive Nitrogen Species Generation in P. infestans Structures

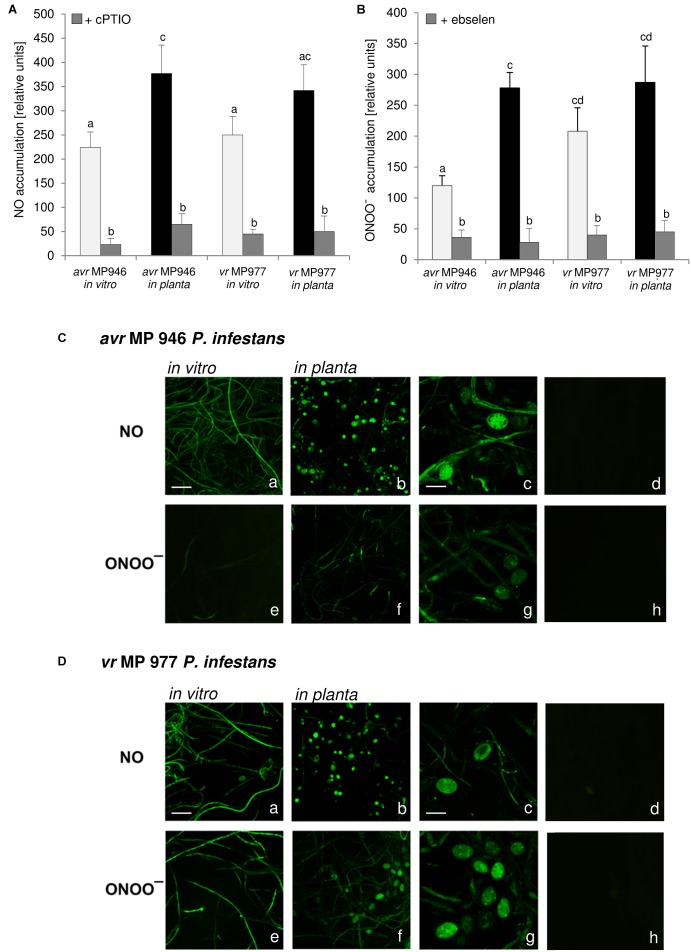

Nitric oxide and ONOO- production in P. infestans growing in vitro and in planta were detected quantitatively using DAF-2DA and APF fluorochrome, respectively. The experiment documented that both isolates, differing in their virulence pattern on the ‘Sarpo Mira’, are able to generate RNS (Figure 1). However, vr MP 977 presented significantly higher levels of ONOO- under in vitro conditions (Figure 1A,B). The interaction with the plant led to boosted ONOO- formation mainly in the avr MP 946 isolate (Figure 1B). Additional real-time imaging of RNS production in both P. infestans isolates revealed green fluorescence localized particularly in hyphae and mature sporangia growing on the medium and in planta, respectively (Figure 1C,D). Importantly, avr MP 946 P. infestans presented far weaker ONOO- formation when growing on the medium and only contact with potato plants provoked a considerable increase in ONOO- emission (Figure 1B,C).

FIGURE 1.

Reactive nitrogen species formation in P. infestans growing under in vitro and in planta conditions. (A) Nitric oxide and (B) peroxynitrite accumulation measured as Cu-Fl and APF fluorescence, respectively. Values represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates derived from three independent experiments (n = 9). Columns marked with the same letter are not significantly different (Dunnett’s test) at p < 0.05. Bio-imaging of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite formation in (C) avr MP 946 and (D) vr MP 977 P. infestans. Pathogen structures growing in vitro (a,e), in planta (b–d, f–h) and in planta in the presence of 1 mM cPTIO (d) or 50 μM ebselen (h). Images show general phenomena representative of three individual experiments. Bars indicate 20 μm (a,b,e,f) and 100 μm (c,d,g,h).

As stated earlier, pathogens belonging to Fungi and fungus-like Oomycetes have active sources of NO and pathways of its detoxication, which defend them against NO-induced damages and ensure the vital level required for the signaling function both in the pathogen physiological state and during host tissue colonization (Arasimowicz-Jelonek and Floryszak-Wieczorek, 2014). Importantly, RNS production observed in P. infestans was accelerated during in planta sporangia development. It can be assumed that NO and ONOO- could mediate nuclear division, or degeneration of a proportion of the nuclei in the sporangium providing sporangia with the ability to release zoospores in rapid succession. The presence of NO was also observed in the infection structures of another oomycete, B. lactucae, grown both on susceptible and resistant lettuce cultivars, however, the plant genotype determined the timing of the pathogen development. A strong NO signal was detected in the tip of the germ tube and the appressorium, which is a prerequisite for tissue penetration. A weaker NO signal was detected in developing primary and secondary vesicles, intracellular hyphae and in haustoria on susceptible lettuce (Sedlárová et al., 2011).

Peroxynitrite Formation in P. infestans Is Accompanied by Protein Tyrosine Nitration

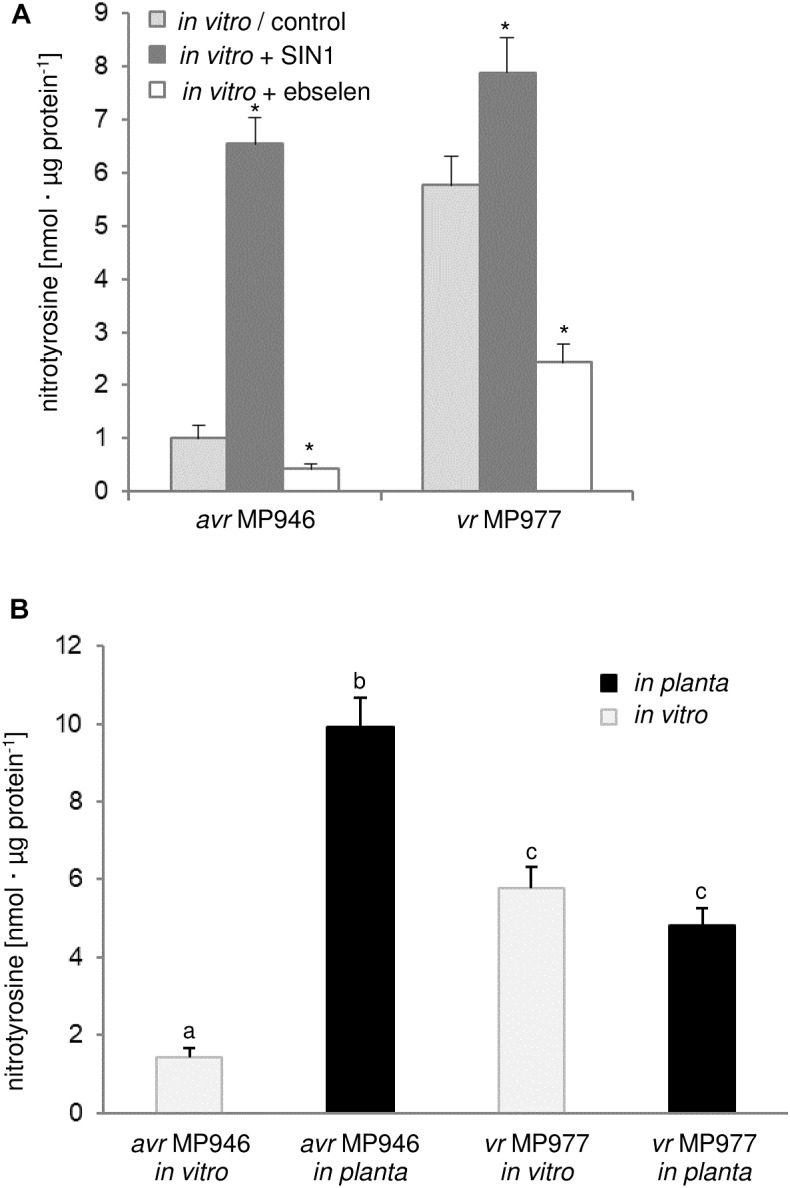

There is evidence that ONOO- fulfills an important role during the plant-pathogen interaction creating a cellular redox milieu toward plant defense expression (Durner et al., 1998; Alamillo and García-Olmedo, 2001; Arasimowicz-Jelonek et al., 2016). However, there is no information available on the ONOO- mode of action in relation to any fungal and fungal-like pathogens. Searching for the functional role of the RNS in P. infestans we identified a protein pool potentially targeted by ONOO- via nitration. Firstly, we analyzed the abundance of nitrated proteins in P. infestans hyphae of avr MP 946 and vr MP 977 isolates during in vitro and in planta conditions (Figure 2). Based on immunoassay we found that the total amount of nitrated proteins varied greatly between isolates during both in vitro and in planta growth phases. A considerable increase in ONOO- formation noted in the avr MP 946 isolate during contact with the host tissues was accompanied by the highest level of the total protein pool undergoing nitration. It was ca. 9-fold greater in comparison to in vitro growth conditions of avr MP 946. In contrast, quantitative changes in the nitrated protein pool of vr MP 977 P. infestans growing in planta revealed only a slightly lowered expression of nitrated proteins (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Quantification of protein Tyr nitration of avr MP 946 and vr MP 977 P. infestans. (A) Quantification of nitrated proteins measured as 3-nitrotyrosine content in avr MP 946 and vr MP 977 P. infestans structures enriched or depleted with ONOO- during in vitro growth; 3-nitrotyrosine content was estimated 5 h after P. infestans pretreatment with 50 μM SIN-1 or 50 μM ebselen; asterisks indicate values that differ significantly from the control (untreated) culture of avr MP 946 or vr MP 977 at ∗p < 0.05. (B) 3-nitrotyrosine content in avr MP 946 and vr MP 977 P. infestans growing under in vitro and in planta conditions; the results were calculated using the standard curve and expressed as nmol 3-nitrotyrosine/μg protein; values represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates derived from three independent experiments (n = 9); columns marked with the same letter are not significantly different (Dunnett’s test) at p < 0.05.

As we indicated before, potato ETI is accompanied by a periodic ca. 3-fold induction of ONOO- production starting within the first hour after challenge with the oomycete (Arasimowicz-Jelonek et al., 2016). Thus, avr MP 946 P. infestans during the contact with potato was exposed to both innate ONOO- and host-derived ONOO- (Arasimowicz-Jelonek et al., 2016; Izbiańska et al., 2018). In consequence, boosted and pathophysiological levels of RNS in planta may result in an elevated level of nitrated proteins within pathogen structures. Moreover, avr MP 946 features a relatively low-efficient strategy to remove RNS and suppress its excessive accumulation (data not presented), which additionally accelerates in planta homeostasis misbalance and promotes pathogen subjugation. In contrast, vr MP 977 seems to be perfectly adapted to both plant- and pathogen-derived RNS production, since only slight fluctuation in the total protein pool undergoing nitration was observed during late blight development. Therefore, changes in the total protein pool undergoing Tyr nitration phenomena in P. infestans structures in response to the host may reflect homeostasis misbalance connected to stress-associated conditions. It is generally accepted that RNS depending on its abundance within the cellular milieu may provoke opposite effects (Yu et al., 2014). An elevated level of ONOO- contributes to oxidative and nitrosative stress in cells and Tyr nitration has been assumed to be a reliable marker of nitro-oxidative stress, since this PTM is frequently associated with pathophysiological states (Corpas et al., 2007). On the other hand, nitrated proteins may also be present in living cells under optimal physiological conditions, which strengthens the hypothesis that via Tyr nitration ONOO- could be involved in cooperation with NO in a broad spectrum of signaling and regulatory processes (Arasimowicz-Jelonek and Floryszak-Wieczorek, 2011; Vandelle and Delledonne, 2011). It should be noted that pathogens may employ nitration phenomenon to cause disease. For example, Streptomyces spp. including S. scabies, S. acidiscabies and S. turgidiscabies produce phytotoxin thaxtomin, a nitrated dipeptide which inhibits cellulose synthesis (Bignell et al., 2014). Moreover, nitration of lipopeptide arylomycin produced by Streptomyces sp. Tü 6075 improves its antibacterial activity (Schimana et al., 2002).

Nitroproteome-Wide Identification of Tyrosine Nitration in P. infestans

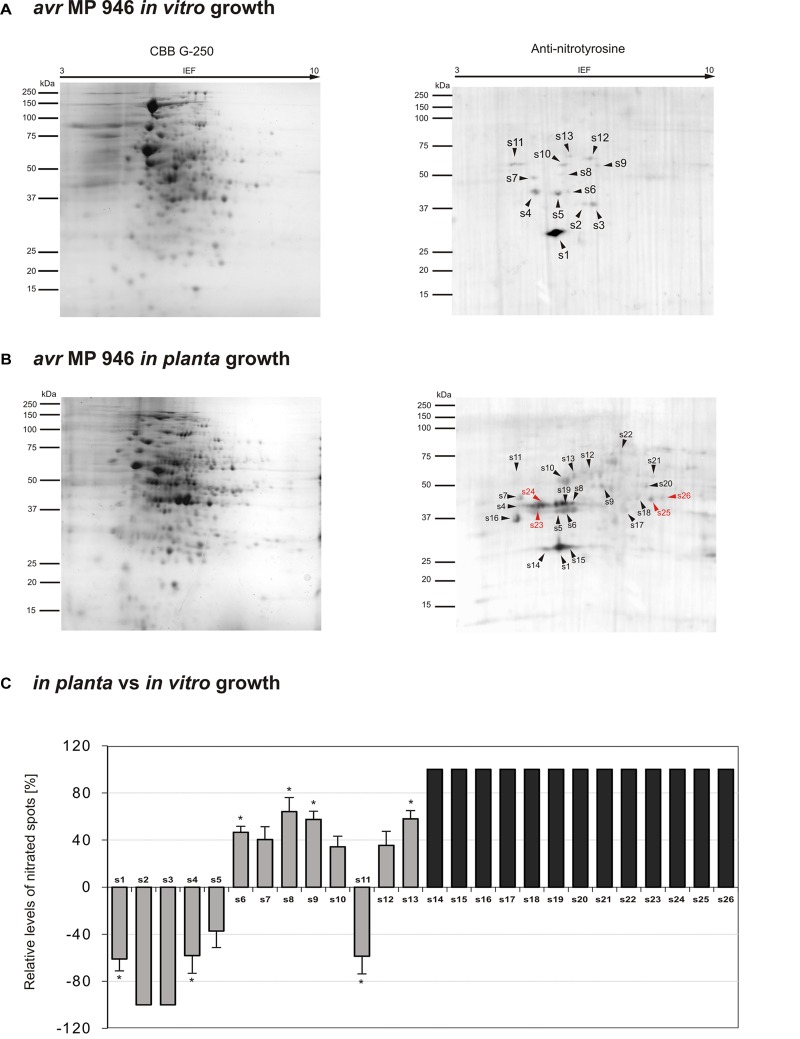

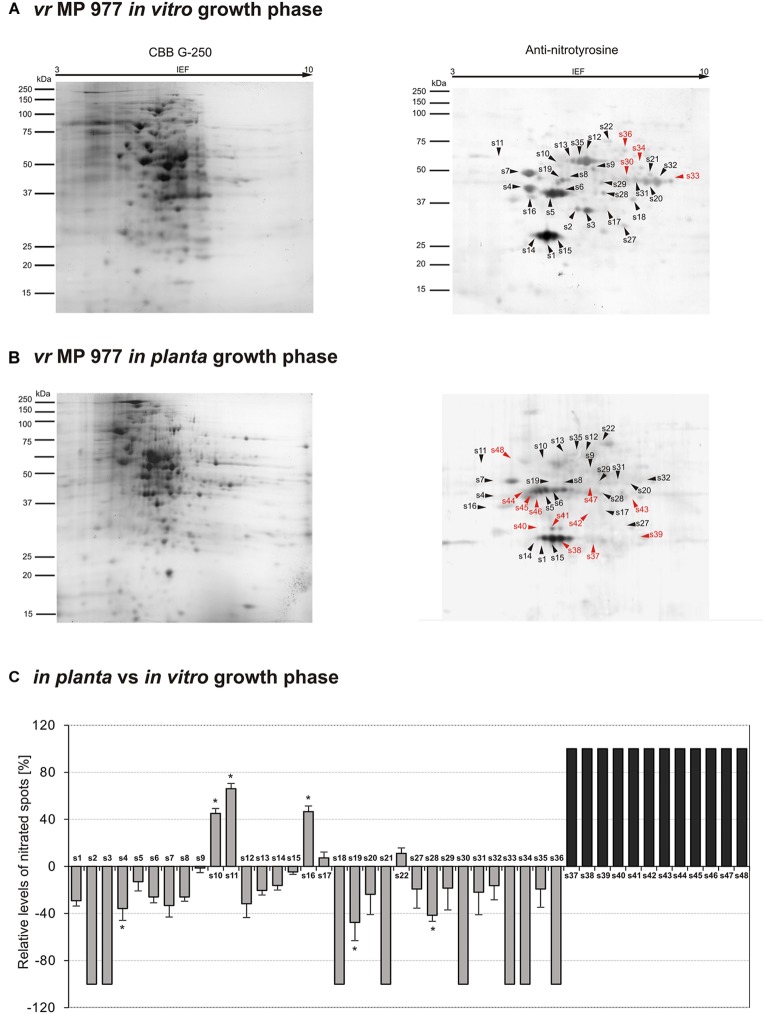

The observed quantitative differences have encouraged us to take the next step aimed at nitrated protein identification. Identification of 3-nitrotyrosine-containing proteins and mapping of nitrated residues is a challenging task due to the limited incidence of this modification in biological samples (Abello et al., 2009). Importantly, a low number of proteins are preferential targets of nitration (usually fewer than 100 proteins per proteome), in contrast with the large number of proteins modified by other post-translational events such as phosphorylation, acetylation and, notably, S-nitrosylation (Batthyány et al., 2017). In our study, Tyr nitration protein patterns of P. infestans isolates during in vitro and in planta growth were detected with an antibody against nitrotyrosine (Figure 3, 4). A total of 48 spots detected in avr MP 946 and vr MP 977 isolates during all three immuno-blot biological replicates were analyzed by LC–MS–MS/MS mass spectrometry after trypsin digestion using the MASCOT search engine to analyze MS data in order to identify proteins from primary-sequence databases. The identified immunopositive proteins are listed in Table 1. In some cases the selected proteins derived from P. infestans were identified as heterogeneous with more than one protein identified within them, however, a majority of spots were homogenous, containing one specific protein and clear identifications was demonstrated (Table 1). However, these proteins should be considered putatively nitrated until the nitration sites have been identified by sequence analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Tyrosine nitration pattern of avr MP 946 P. infestans growing (A) in vitro and (B) in planta. Representative 2D electrophoresis (pH 3–10 for the first dimension) of avr P. infestans stained with CBB G-250 and representative immunoblots probed with a polyclonal antibody against nitrotyrosine diluted at 1:1000. Molecular-mass standards (kDa) are indicated on the left. Arrowheads indicate all the immunoreactive spots, the symbols (s1–s26) refer to the proteins listed in Table 1. Red arrowheads indicate spots specific to the avr MP 946 P. infestans growing phase. (C) The quantitative results of protein Tyr nitration were calculated by summing the pixels intensity within each protein spot image, and the data were presented in comparison to the control sample average of 0 (control – in vitro growth phase of avr MP 946 P. infestans). Asterisks indicate values that differ significantly from the control at ∗p < 0.05.

FIGURE 4.

Tyrosine nitration pattern of vr MP 977 P. infestans growing (A) in vitro and (B) in planta. Representative 2D electrophoresis (pH 3–10 for the first dimension) of avr P. infestans stained with CBB G-250 and representative immunoblots probed with a polyclonal antibody against nitrotyrosine diluted at 1:1000. Molecular-mass standards (kDa) are indicated on the left. Arrowheads indicate all the immunoreactive spots, the symbols (s1–s48) refer to the proteins listed in Table 1. Red arrowheads indicate spots specific to the vr MP 977 P. infestans growing phase. (C) The quantitative results of protein Tyr nitration were calculated by summing the pixels intensity within each protein spot image, and the data were presented in comparison to the control sample average of 0 (control – in vitro growth phase of vr MP 977 P. infestans). Asterisks indicate values that differ significantly from the control at ∗p < 0.05.

Table 1.

Nitrated proteins in P. infestans growing in vitro and in planta isolated from PVDF membrane and identified by LC-MS-MS/MS.

| No. | Protein name | Score | Gene ID | Functional category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 105 | PITG_12377 | Nucleobase-containing compound metabolism |

| S2 | Histone H4∗ | 110 | PITG_03552 | Nucleobase-containing compound metabolism |

| S3 | Tubulin alpha chain∗ | 94 | PITG_07996 | Cytoskeleton organization |

| S4 | Heat shock protein 90∗ 14-3-3 protein epsilon Calmodulin∗ |

138 137 91 |

PITG_06415 PITG_19017 PITG_06514 | Cell redox homeostasis / response to stress Signal transduction Signal transduction |

| S5 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase∗ Histone H3∗ Peroxiredoxin-2∗ |

76 60 56 |

PITG_02786 PITG_03551 PITG_15492 | Carbohydrate metabolism / energy metabolism Nucleobase-containing compound metabolism Cell redox homeostasis / response to stress |

| S6 | PREDICTED: ATP-dependent RNA helicase SUPV3L1 | 122 | PITG_11795 | Nucleobase-containing compound metabolism |

| S7 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 72 | PITG_00319 | Proteolysis / protein metabolism |

| S8 | PREDICTED: Structural maintenance of chromosomes protein | 60 | PITG_05757 | Nucleobase-containing compound metabolism |

| S9 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 137 | PITG_12490 | Signal transduction |

| S10 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 1, mitochondrial | 60 | PITG_06815 | Pathogenesis |

| S11 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase∗ | 95 | PITG_01938 | Carbohydrate metabolism / energy metabolism |

| S12 | Putative uncharacterized protein Actin-like protein |

152 78 |

PITG_06853 PITG_15078 | Endonuclease activity / protein metabolism Cytoskeleton organization |

| S13 | Xanthine dehydrogenase | 58 | PITG_02284 | Oxidation-reduction process / others |

| S14 | PREDICTED: Secreted RxLR effector peptide protein, (fragment) Secreted RxLR effector peptide protein PREDICTED: Secreted RxLR effector peptide protein |

25 20 19 |

PITG_05074 PITG_23137 PITG_15764 |

Signal transduction / pathogenesis Signal transduction / pathogenesis Signal transduction / pathogenesis |

| S15 | Triosephosphate isomerase∗ | 144 | PITG_13116 | Carbohydrate metabolism / energy metabolism |

| S16 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 | 728 | PITG_17261 | Ribosome biogenesis / protein metabolism |

| S17 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-2-like protein | 343 | PITG_09556 | Ribosome biogenesis /signal transduction |

| S18 | Aspartate aminotransferase | 574 | PITG_02256 | Carbohydrate metabolism / energy metabolism |

| S19 | PREDICTED: NmrA-like family protein | 216 | PITG_14492 | Cell redox homeostasis / response to stress |

| S20 | Glutamate dehydrogenase∗ | 194 | PITG_07671 | Nitrogen metabolism / protein metabolism |

| S21 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 143 | PITG_13946 | Signal transduction |

| S22 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | 1178 | PITG_10210 | Carbohydrate metabolism / energy metabolism |

| S23 | PREDICTED: Secreted RxLR effector peptide protein | 24 | PITG_06059 | Hydrolase activity / pathogenesis |

| S24 | PREDICTED: Alcohol dehydrogenase | 103 | PITG_10292 | Oxidoreductase activity / others |

| S25 | PREDICTED: Type I inositol-3,4-bisphosphate 4-phosphatase | 48 | PITG_12548 | Signal transduction |

| S26 | Peroxiredoxin-like protein∗ | 123 | PITG_00585 | Cell redox homeostasis / response to stress |

| S27 | Carbonic anhydrase∗ | 292 | PITG_00682 | Carbohydrate metabolism / energy |

| S28 | PREDICTED: Secreted RxLR effector peptide protein | 23 | PITG_04081 | Signal transduction / pathogenesis |

| S29 | PREDICTED: Voltage-gated potassium channel subunit beta | 184 | PITG_03719 | Transport / signal transduction |

| S30 | PREDICTED: Secreted RxLR effector peptide protein | 22 | PITG_01904 | Signal transduction / pathogenesis |

| S31 | Transient receptor potential Ca2 channel (TRP-CC) family protein | 86 | PITG_05737 | Signal transduction |

| S32 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein Histone H2B |

205 114 |

PITG_11244 PITG_03550 | Cell redox homeostasis / response to stress Nucleobase-containing compound metabolism |

| S33 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 74 | PITG_16013 | Unclassified |

| S34 | PREDICTED: NAD-specific glutamate dehydrogenase | 71 | PITG_08802 | Nitrogen metabolism / protein metabolism |

| S35 | PREDICTED: Inositol-3-phosphate synthase Pyruvate kinase∗ |

404 91 |

PITG_01700 PITG_09400 |

Lipid metabolism / energy metabolism Carbohydrate metabolism / energy metabolism |

| S36 | 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase, mitochondrial | 187 | PITG_07197 | Lipid metabolism / energy metabolism |

| S37 | Crinkler (CRN) family protein | 28 | PITG_23273 | Host-translocated effectors / pathogenesis |

| S38 | Triosephosphate isomerase∗ | 122 | PITG_16048 | Carbohydrate metabolism / energy metabolism |

| S39 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 77 | PITG_12486 | tRNA processing / nucleobase-containing compound metabolism |

| S40 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 78 | PITG_00160 | Signal transduction |

| S41 | Crinkler (CRN) family protein | 24 | PITG_20172 | Host-translocated effectors / pathogenesis |

| S42 | Prohibitin | 210 | PITG_00827 | DNA replication / nucleobase-containing compound metabolism |

| S43 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 114 | PITG_01555 | Cytoskeleton organization |

| S44 | Serine/threonine protein kinase | 99 | PITG_14221 | Protein phosphorylation / signal transduction |

| S45 | Syntaxin-like protein | 42 | PITG_01470 | Intracellular protein transport / signal transduction |

| S46 | PREDICTED: Choline/Carnitine O-acyltransferase | 42 | PITG_17907 | Transferase activity / other |

| S47 | 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate coenzyme A ligase, mitochondrial | 89 | PITG_03685 | Oxidation-reduction process / other |

| S48 | ATP synthase subunit beta | 533 | PITG_06595 | ATP metabolic process / energy metabolism |

Asterisks indicate proteins which have previously been functionally confirmed as nitrated in animal or plant systems.

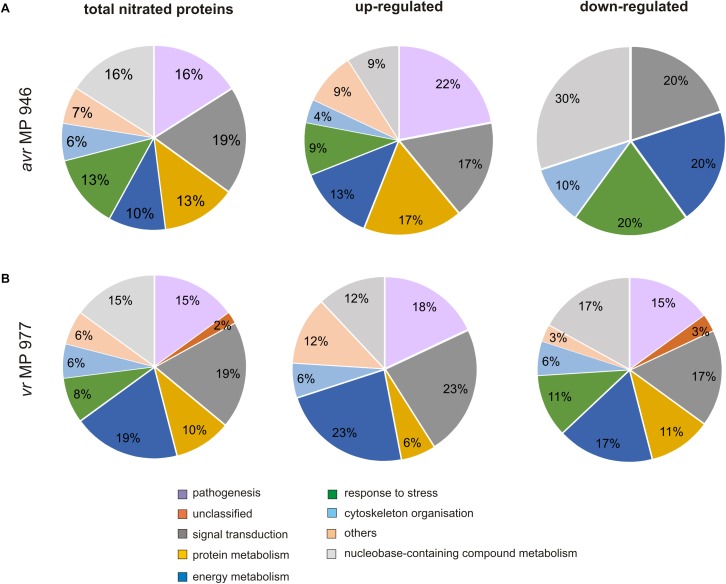

To gain further insights into the nitroproteome of P. infestans, the proteins identified from both pathogen isolates were classified into nine functional categories corresponding to different biological processes, which are displayed in Figure 5. The category containing the highest number of identified protein candidates for nitration in both isolates is related to signal transduction (19%), followed by proteins related to metabolic process requiring nucleobase containing compounds (15–16%) and pathogenesis (15–16%). Importantly, in vr MP 977, the proteins associated with energy metabolism constituted the most-represented functional category in addition to proteins involved in signal transduction (19%) (Figure 5B). These results indicate that the nitrated proteins, widely distributed within pathogen structures, are involved in a variety of processes in P. infestans.

FIGURE 5.

Functional classification and distribution of 48 nitrated protein spots identified by LC–MS–MS/MS analysis in (A) avr MP 946 and (B) vr MP 977 P. infestans. The area for each group indicates the relative percentage of proteins (%) in that group. The color code represents the functional classification according to the UniProt database.

Importantly, 12 of the identified proteins have previously been functionally confirmed to be nitrated in animal or plant systems (Table 1). These include histones H3, H4 and pyruvate kinase (Ghesquière et al., 2009), tubulin alpha chain (Tedeschi et al., 2005), heat shock protein 90 (Franco et al., 2013), calmodulin (Smallwood et al., 2003), peroxiredoxin-2 (Randall et al., 2014, 2016), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Palamalai and Miyagi, 2010), fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase (Koeck et al., 2004), glutamate dehydrogenase (Piszkiewicz et al., 1971), carbonic anhydrase (Chaki et al., 2013) and triosephosphate isomerase (Gao et al., 2017).

P. infestans Virulence Pattern Determine Nitroproteome Status

Proteomic analysis of nitrated proteins in hyphae of avr MP 946 P. infestans resulted in the identification of 13 spots during in vitro (Figure 3A) and 24 spots during in planta phases, respectively (Figure 3B). Eleven protein spots were found to be common for both growth conditions; in turn, as many as 2 (s2, s3) spots were specific to in vitro growth and 13 (s14–s26) spots were specific to in planta growth (Figure 3C in gray color). Importantly, 4 out of 13 spots appearing in planta were exclusively nitrated in hyphae of avr MP 946 P. infestans growing on potato (s23–s26, Figure 3B in red color). These 4 unique candidates for nitration included secreted RXLR effector peptide protein (predicted), alcohol dehydrogenase (predicted), type I inositol-3,4-bisphosphate 4-phosphatase (predicted) and peroxiredoxin-like protein.

The comparative analyses of the obtained nitroproteome maps revealed that the in planta phase of avr MP 946 was accompanied by a lowered expression of 3 common spots (s1, s4, s5), whereas the presence of 2 spots (s2, s3) was no longer detected (Figure 3C). Interestingly, these reduced/absent nitrated proteins included proteins involved mainly in cellular redox homeostasis and signal transduction (Table 1). Additionally, the in planta phase of avr MP 946 revealed diminished expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (s11).

Abundance profiles of nitrated proteins showed that 7 protein spots (s6–s10, s12, s13) were upregulated and 13 appeared de novo (s14–s26) during in planta hyphal growth of avr MP 946 (Figure 3C), however, only 4 of them (s10, s16, s17, s22) were common with vr MP 977 growing in planta (Figure 4C). These highly abundant spots included proteins involved in protein and carbohydrate metabolisms, signal transduction and pathogenesis (Table 1).

The qualitative nitroproteome analysis of the vr MP 977 P. infestans isolate resulted in the identification of a wider spectrum of nitrated proteins in comparison to the avr MP 946 (Figure 4). Nitroproteome maps revealed 32 spots during in vitro (Figure 4A) and 36 spots during in planta phases (Figure 4B). Twenty four protein spots were found to be common for both growth conditions. As many as 8 (s2, s3, s18, s21, s30, s33, s34, and s36) spots were specific to in vitro growth and 4 of them (s30, s33, s34, and s36 in red color) were indicated as exclusively nitrated in hyphae of vr MP 977 P. infestans growing in vitro (Figure 4A). In turn, during in planta growth we identified 12 (s37–s48) specific spots and all of them were marked as exclusively nitrated in hyphae of MP 977 P. infestans growing on potato (Figure 4B,C in gray color). The vr MP 977-specific candidates for nitration included two crinkler (CRN) family proteins, triosephosphate isomerase, prohibitin, serine/threonine protein kinase, syntaxin-like protein, choline/carnitine O-acyltransferase, 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate coenzyme A ligase (predicted), a mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit beta and three uncharacterized proteins.

Apart from the nitrated proteins common with avr MP 946 (s1–s5), analyses of the vr MP 977 isolate in the in planta phase showed a diminished expression of 16 other protein spots (s6–s9, s12–s15, s19, s20, s27–s29, s31, s32, s35), while the presence of 6 spots (s18, s21, s30, s33, s34, s36) was no longer detected (Figure 4C). These protein spots contain protein associated with carbohydrate/lipid metabolisms, oxidation-reduction processes and pathogenesis (Table 1).

Additionally, 5 spots (s10, s11, s16, s17, s22) were upregulated and 12 (s37–s48) appeared de novo in vr MP 977 when growing in planta. Interestingly, these 12 spots were found to be unique for vr MP 977 (Figure 4C) and the identified amino acid sequences (Supplementary Table S1) corresponded to the protein involved mainly in the processes of protein metabolism and signal transduction (Table 1).

Identification and Metabolic Fate of the Differentially Expressed Nitrated Proteins of P. infestans During an Interaction With the Host

Post-translational modifications are some of the most important mechanisms activating, changing or suppressing protein functions in living organisms. Targeted nitration via ONOO- could control protein structure and in consequence reversibly or irreversibly downregulate its activity (Yakovlev and Mikkelsen, 2010; Sengupta and Bhattacharjee, 2016). Alternatively, selective Tyr nitration regulates enzyme catalytic attributes or does not affect protein activity completely (Daiber et al., 2013). Based on this assumption, protein nitration may have biological consequences comparable with those of protein phosphorylation, i.e., may be involved in redox signaling (Kanski and Schoneich, 2005). Thus, the pool of nitrated proteins expressed in P. infestans could correspond to proteins in their inactive configuration reinforcing nitro-oxidative signaling.

Identification of immunoreactive spots, which expression in planta was downregulated in both P. infestans isolates, indicated NO-dependent events connected with primary metabolism, including nitration of proteins involved in the nucleobase-containing compound and carbohydrate metabolism, cytoskeleton organization, signal transduction and cell redox homeostasis. One of the identified nitrated proteins engaged in signal transduction was calmodulin (PITG_06514). It is well known that calmodulin is a calcium binding protein that serves as a molecular switch to regulate a network of the Ca2+ signaling pathway (Johnson, 2006). Importantly, recent studies indicate essential roles for cytoplasmic Ca2+ in the regulation of most aspects of oomycete biology, including pathogen virulence (Zheng and Mackrill, 2016). According to Zheng et al. (2018), the P. infestans RXLR effector SFI5 requires association with calmodulin for PTI suppressing activity. Thus, the substantially reduced pool of nitrated calmodulin (PITG_06514) in planta could favor the P. infestans offensive strategy. As it was also noted in planta in vr MP 977, the downregulated nitration of the transient receptor potential (TRP) channel superfamily (PITG_05737) and voltage-gated potassium channels (VGCC) (PITG_03719), which can act as Ca2+ channels, may have numerous effects on the regulation of oomycete Ca2+ signaling during host colonization. It is worth pointing that next to cell redox homeostasis, also heat shock proteins (Hsps) have been implicated in fungal pathogenicity. As it was indicated by Martinez-Rossi et al. (2017), Hsps display specific roles in fungi, such as dimorphic transition, antifungal resistance and virulence. Among the identified proteins in vr MP 977 showing a decreased nitration in planta, three were related to cell redox homeostasis. One of these proteins (PITG_14492) is a member of the NmrA-like family and could act as a redox sensor and regulator of transcription (Lamb et al., 2003). Thus, NmrA-like proteins might detect the degree of host defense response and contribute to the effective regulation of the pathogen’s offensive strategy. Importantly, the avr P. infestans-potato interaction was accompanied by elevated NmrA-like protein nitration.

It should be noted that energy metabolism is an important target for NO during P. infestans in planta growth. Diminished expression of nitrated proteins during in planta growth of vr MP 977 involved many metabolic regulators, including enzymes that may mobilize reserves and maintain energy homeostasis. These proteins included triosephosphate isomerase, aspartate aminotransferase, carbonic anhydrase, pyruvate kinase, inositol-3-phosphate synthase and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase. Thus, the decreased expression of nitrated proteins involved in carbohydrate and lipid pathways during in planta growth might accelerate energy and metabolic intermediates in P. infestans infection structures. Moreover, in order to export cell wall components and defend against host-derived toxic compounds plants need to mobilize stored energy reserves (Resjö et al., 2017). Importantly, five other nitrated proteins engaged in energy metabolism were either found in greater amounts or appeared de novo.

Four of the NO-regulated proteins identified in both P. infestans isolates during the in planta phase were involved in nucleic acid metabolisms. Two of these proteins, i.e., nitrated ATP-dependent RNA helicase SUPV3L1 and the structural maintenance of chromosome protein were oppositely expressed in the analyzed isolates and upregulation of these proteins was observed only in avr MP 946. This could reflect the importance of this protein group as the main target for nitration during interactions with the plant. The relevance of the proper metabolism regulation of nucleobase-containing compounds for pathogen survival within the host was postulated earlier, since defects in nucleic acid metabolism may lead to an inappropriate activation of nucleic acid sensors (Lee-Kirsch, 2010; Sharma et al., 2015).

Among the identified nitrated proteins related to signal transduction, four showed an increased expression or appeared de novo in both isolates, however, only guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-2-like protein (PITG_09556) revealed common upregulation. This PTM may result in synergistic or antagonistic relations between signaling hubs and modulate signal transduction attenuating pathogen offensive.

Several proteins related to pathogenicity sensu stricto were also found to be nitrated in P. infestans. The genome of P. infestans is one of the largest among oomycetes (240 Mb), containing an extremely large pool of predicted genes coding for disease-promoting effector proteins, leading to an exceptionally high potential to adapt to new control strategies of the potato crop. In P. infestans these predicted host-translocated effectors encompass the RXLR (containing the conserved motif RXLR for arginine, any amino acid, leucine, and arginine) and CRN (crinkler or crinkling- and necrosis-inducing protein) effectors. These are large and complex protein families, with around 560 RXLRs and 200 CRNs members encoded in the genome (Meijer et al., 2014), allowing oomycetes to manipulate plant immunity and promote infection. Some of the RXLR and CRN effectors have been experimentally verified, and their function as virulence and avirulence factors have been elucidated (Haas et al., 2009). Importantly, we detected a relatively large quantity of potentially nitrated cytosolic RXLR (5 identified) and CRN (2 identified) effectors, which were differentially expressed during in planta growth. In the case of the avr MP 946 isolate, nitration of RXLRs (PITG_23137, PITG_06059) was upregulated, whereas in vr MP 977 all identified RXLRs (PITG_01904, PITG_04081, PITG_22813) exhibited downregulated expression. Moreover, the vr P. infestans–potato interaction resulted in nitration of two CRN effectors (PITG_23273, PITG_20172). Since P. infestans has the capacity to rapidly change its repertoire of effectors and thereby escape recognition by resistant potato varieties, the PTM of effector proteins seems to be a promising signpost for further analysis. NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 1 (PITG_06815) was one of the pathogenicity-related proteins that were more abundant in both isolates growing in planta. Moreover, another putative pathogenicity related protein included actin like protein (PITG_15078), playing an important role during appressorium formation in this filamentous organism (Kots et al., 2017).

Intriguingly, three of the proteins that we found to be nitrated, were also identified as potentially phosphorylated on Tyr residues (Resjö et al., 2014). These include actin-like proteins (PITG_15078; s12), heat shock 70 kDa protein (PITG_11244; s32) and serine/threonine protein kinase (PITG_14221; s44). Several reports point to a dynamic interplay between protein Tyr nitration and phosphorylation, which is dependent on the concentration of nitrating agents in the biological milieu. Competition between phosphorylation and nitration occurs within the same sensitive Tyr residue. While Tyr phosphorylation is induced at lower concentrations of peroxynitrite, at relatively higher amounts the process is inactivated and it is also irreversible (Sengupta and Bhattacharjee, 2016). Although the competition correlation between phosphorylation and nitration is as yet poorly understood, it might partially explain the dynamic change in nitroproteome during the switch between in vitro and in planta pathogen growth.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, presented findings contribute further insight into P. infestans molecular biology and for the first time indicate protein Tyr nitration as a common phenomenon within pathogen structures, engaged in the regulation of metabolic activities under in vitro and in planta conditions. Thus, the nitroproteome should be considered as a flexible element of the oomycete adaptation strategy to different micro-environments.

Definitely, due to the increased awareness of fungicide effects and the phasing out of various effective crop protection compounds, the identification of NO-mediated functional modifications may contribute to improvements in modern potato protection strategies against late blight disease.

Author Contributions

MA-J and JF-W planned and designed the research. KI performed the experiments. KI, JGa, and JGz collected and analyzed the data. TJ performed the statistical analysis. MA-J wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the grant of National Science Centre (Project No. NCN 2014/13/B/NZ9/02177).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01516/full#supplementary-material

The index of disease development on potato leaves at 9 dpi with avr MP 946 and vr MP 977 P. infestans based on a I–IV point scale, which represents the percentage of leaf area covered by late blight symptoms. Values are means of average disease indexes from 10 leaves from three independent experiments.

Tyrosine nitration pattern of avr MP 946 (A) and vr MP 977 (B) P. infestans growing in vitro and in planta conditions, using 10 mM sodium dithionite as control of anti-nitrotyrosine antibody specificity. Treatment PVDF membranes with sodium dithionite (prior to incubation with the polyclonal antibody against nitrotyrosine diluted at 1:1000) converts nitrotyrosine in aminotyrosine, allowing the detection of false positive spots. Molecular-mass standards (kDa) are indicated on the left.

Amino acid sequence of the identified homologous proteins (matched peptides derived from P. infestans shown in bold red).

References

- Abello N., Kerstjens H. A., Postma D. S., Bischoff R. (2009). Protein tyrosine nitration: selectivity, physicochemical and biological consequences, denitration, and proteomics methods for the identification of tyrosine-nitrated proteins. J. Proteome Res. 8 3222–3238. 10.1021/pr900039c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aburima A., Riba R., Naseem K. M. (2010). Peroxynitrite causes phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein through a PKC dependent mechanism. Platelets 21 421–428. 10.3109/09537104.2010.483296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamillo J. M., García-Olmedo F. (2001). Effects of urate, a natural inhibitor of peroxynitrite-mediated toxicity, in the response of Arabidopsis thaliana to the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae. Plant J. 25 529–540. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00984.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arasimowicz-Jelonek M., Floryszak-Wieczorek J. (2011). Understanding the fate of peroxynitrite in plant cells – from physiology to pathophysiology. Phytochemistry 72 681–688. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arasimowicz-Jelonek M., Floryszak-Wieczorek J. (2014). Nitric oxide: an effective weapon of the plant or the pathogen? Mol. Plant Pathol. 15 406–416. 10.1111/mpp.12095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arasimowicz-Jelonek M., Floryszak-Wieczorek J. (2016). Nitric oxide in the offensive strategy of fungal and oomycete plant pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 7:252. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arasimowicz-Jelonek M., Floryszak-Wieczorek J., Izbiańska K., Gzyl J., Jelonek T. (2016). Implication of peroxynitrite in defense responses of potato to Phytophthora infestans. Plant Pathol. 65 754–766. 10.1111/ppa.12471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asai S., Yoshioka H. (2009). Nitric oxide as a partner of reactive oxygen species participates in disease resistance to nectrotophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea in Nicotiana benthamiana. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22 619–629. 10.1094/MPMI-22-6-0619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartesaghi S., Ferrer-Sueta G., Peluffo G., Valez V., Zhang H., Kalyanaraman B., et al. (2007). Protein tyrosine nitration in hydrophilic and hydrophobic environments. Amino Acids 32 501–515. 10.1007/s00726-006-0425-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartesaghi S., Radi R. (2018). Fundamentals on the biochemistry of peroxynitrite and protein tyrosine nitration. Redox Biol. 14 618–625. 10.1016/j.redox.2017.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batthyány C., Bartesaghi S., Mastrogiovanni M., Lima A., Demicheli V., Radi R. (2017). Tyrosine-nitrated proteins: proteomic and bioanalytical aspects. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 26 313–328. 10.1089/ars.2016.6787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begara-Morales J. C., Sánchez-Calvo B., Chaki M., Mata-Pérez C., Valderrama R., Padilla M. N., et al. (2015). Differential molecular response of monodehydroascorbate reductase and glutathione reductase by nitration and S-nitrosylation. J. Exp. Bot. 66 5983–5996. 10.1093/jxb/erv306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellin D., Asai S., Delledonne M., Yoshioka H. (2013). Nitric oxide as a mediator for defense responses. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 26 271–277. 10.1094/MPMI-09-12-0214-CR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignell D. R. D., Fyans J. K., Cheng Z. (2014). Phytotoxins produced by plant pathogenic Streptomyces species. J. Appl. Microbiol. 116 223–235. 10.1111/jam.12369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Both M., Eckert S. E., Csukai M., Müller E., Dimopoulos G., Spanu P. D. (2005). Transcript profiles of Blumeria graminis development during infection reveal a cluster of genes that are potential virulence determinants. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18 125–133. 10.1094/MPMI-18-0125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilising the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72 248–254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaki M., Carreras A., López-Jaramillo J., Begara-Morales J. C., Sánchez-Calvo B., Valderrama R., et al. (2013). Tyrosine nitration provokes inhibition of sunflower carbonic anhydrase (β-CA) activity under high temperature stress. Nitric Oxide 29 30–33. 10.1016/j.niox.2012.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaki M., Fernández-Ocaña A. M., Valderrama R., Carreras A., Esteban F. J., Luque F., et al. (2009a). Involvement of reactive nitrogen and oxygen species (RNS and ROS) in sunflower-mildew interaction. Plant Cell Physiol. 50 265–279. 10.1093/pcp/pcn196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaki M., Valderrama R., Fernández-Ocaña A. M., Carreras A., López-Jaramillo J., Luque F., et al. (2009b). Protein targets of tyrosine nitration in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) hypocotyls. J. Exp. Bot. 60 4221–4234. 10.1093/jxb/erp263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpas F. J., Carreras A., Valderrama R., Chaki M., Palma J. M., del Río L. A., et al. (2007). Reactive nitrogen species and nitrosative stress in plants. Plant Stress 1 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Daiber A., Daub S., Bachschmid M., Schildknecht S., Oelze M., Steven S., et al. (2013). Protein tyrosine nitration and thiol oxidation by peroxynitrite-strategies to prevent these oxidative modifications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 7542–7570. 10.3390/ijms14047542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durner J., Wendehenne D., Klessig D. F. (1998). Defense gene induction in tobacco by nitric oxide, cyclic GMP, and cyclic ADP-ribose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 10328–10333. 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes G. A. (2012). Using host resistance to manage potato late blight with particular reference to developing countries. Potato Res. 55 205–216. 10.1007/s11540-012-9222-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franco M. C., Ye Y., Refakis C. A., Feldman J. L., Stokes A. L., Basso M., et al. (2013). Nitration of Hsp90 induces cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 1102–1111. 10.1073/pnas.1215177110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W., Zhao J., Li H., Gao Z. (2017). Triosephosphate isomerase tyrosine nitration induced by heme–NaNO2–H2O2 or peroxynitrite: effects of different natural phenolic compounds. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 36:e21893. 10.1002/jbt.21893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghesquière B., Colaert N., Helsens K., Dejager L., Vanhaute C., Verleysen K., et al. (2009). In vitro and in vivo protein-bound tyrosine nitration characterized by diagonal chromatography. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8 2642–2652. 10.1074/mcp.M900259-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenacre S. A., Ischiropoulos H. (2001). Tyrosine nitration: localisation, quantification, consequences for protein function and signal transduction. Free Radic. Res. 34 541–581. 10.1080/10715760100300471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas B. J., Kamoun S., Zody M. C., Jiang R. H., Handsaker R. E., Cano L. M., et al. (2009). Genome sequence and analysis of the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Nature 461 393–398. 10.1038/nature08358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izbiańska K., Floryszak-Wieczorek J., Gajewska J., Meller B., Kuźnicki D., Arasimowicz-Jelonek M. (2018). RNA and mRNA nitration as a novel metabolic link in potato immune response to Phytophthora infestans. Front. Plant Sci. 9:672. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W. C. (1971). An illustrated series of assessment keys for plant diseases, their preparation and usage. Can. Plant Dis. Surv. 51 39–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y., Neverova I., Van Eyk J. E., Bennett B. M. (2006). Nitration of tyrosine 92 mediates the activation of rat microsomal glutathione S-transferase by peroxynitrite. J. Biol. Chem. 281 1986–1991. 10.1074/jbc.M509480200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C. K. (2006). Calmodulin, conformational states, and calcium signaling. A single-molecule perspective. Biochemistry 45 14233–14246. 10.1021/bi061058e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanski J., Schoneich C. (2005). Protein nitration in biological aging: proteomic and tandem mass spectrometric characterization of nitrated sites. Methods Enzymol. 396 160–171. 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)96016-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeck T., Levison B., Hazen S. L., Crabb J. W., Stuehr D. J., Aulak K. S. (2004). Tyrosine nitration impairs mammalian aldolase A activity. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3 548–557. 10.1074/mcp.M300141-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kots K., Meijer H. J. G., Bouwmeester K., Govers F., Ketelaar T. (2017). Filamentous actin accumulates during plant cell penetration and cell wall plug formation in Phytophthora infestans. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 74 909–920. 10.1007/s00018-016-2383-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb H. K., Leslie K., Dodds A. L., Nutley M., Cooper A., Johnson C., et al. (2003). The negative transcriptional regulator NmrA discriminates between oxidized and reduced dinucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 278 32107–32114. 10.1074/jbc.M304104200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Kirsch M. A. (2010). Nucleic acid metabolism and systemic autoimmunity revisited. Arthritis Rheum. 62 1208–1212. 10.1002/art.27372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Rossi N. M., Peres N. T., Rossi A. (2017). Pathogenesis of dermatophytosis: sensing the host tissue. Mycopathologia 182 215–227. 10.1007/s11046-016-0057-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méchin V., Damerval C., Zivy M. (2007). Total protein extraction with TCA-acetone. Methods Mol. Biol. 355 1–8. 10.1385/1-59745-227-0:1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer H. J., Mancuso F. M., Espadas G., Seidl M. F., Chiva C., Govers F., et al. (2014). Profiling the secretome and extracellular proteome of the potato late blight pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13 2101–2113. 10.1074/mcp.M113.035873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro H. P., Arai R. J., Travassos L. R. (2008). Protein tyrosine phosphorylation and protein tyrosine nitration in redox signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10 843–889. 10.1089/ars.2007.1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mur L. A., Carver T. L., Prats E. (2006). NO way to live; the various roles of nitric oxide in plant–pathogen interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 57 489–505. 10.1093/jxb/erj052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamalai V., Miyagi M. (2010). Mechanism of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase inactivation by tyrosine nitration. Protein Sci. 19 255–262. 10.1002/pro.311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perchepied L., Balagué C., Riou C., Claudel-Renard C., Rivière N., Grezes-Besset B., et al. (2010). Nitric oxide participates in the complex interplay of defense-related signaling pathways controlling disease resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23 846–860. 10.1094/MPMI-23-7-0846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piszkiewicz D., Landon M., Smith E. L. (1971). Bovine glutamate dehydrogenase. Loss of allosteric inhibition by guanosine triphosphate and nitration of tyrosine-412. J. Biol. Chem. 246 1324–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piterková J., Hofman J., Mieslerová B., Sedláøová M., Luhová L., Lebeda A., et al. (2011). Dual role of nitric oxide in Solanum spp.–Oidium neolycopersici interactions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 74 37–44. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2011.04.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prats E., Carver T. L. W., Mur L. A. J. (2008). Pathogen-derived nitric oxide influences formation of the appressorium infection structure in the phytopathogenic fungus Blumeria graminis. Res. Microbiol. 159 476–480. 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radi R. (2013). Protein tyrosine nitration: biochemical mechanisms and structural basis of functional effects. Acc. Chem. Res. 46 550–559. 10.1021/ar300234c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall L., Manta B., Nelson K. J., Santos J., Poole L. B., Denicola A. (2016). Structural changes upon peroxynitrite-mediated nitration of peroxiredoxin 2; nitrated Prx2 resembles its disulfide-oxidized form. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 590 101–108. 10.1016/j.abb.2015.11.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall L. M., Manta B., Hugo M., Gil M., Batthyàny C., Trujillo M., et al. (2014). Nitration transforms a sensitive peroxiredoxin 2 into a more active and robust peroxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 289 15536–15543. 10.1074/jbc.M113.539213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymundo R., Asseng S., Robertson R., Petsakos A., Hoogenboom G., Quiroz R., et al. (2018). Climate change impact on global potato production. Eur. J. Agric. 100 87–98. 10.1016/j.eja.2017.11.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resjö S., Ali A., Meijer H. J., Seidl M. F., Snel B., Sandin M., et al. (2014). Quantitative label-free phosphoproteomics of six different life stages of the late blight pathogen Phytophthora infestans reveals abundant phosphorylation of members of the CRN effector family. J. Proteome Res. 13 1848–1859. 10.1021/pr4009095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resjö S., Brus M., Ali A., Meijer H. J. G., Sandin M., Govers F., et al. (2017). Proteomic analysis of Phytophthora infestans reveals the importance of cell wall proteins in pathogenicity. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 16 1958–1971. 10.1074/mcp.M116.065656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samalova M., Johnson J., Illes M., Kelly S., Fricker M., Gurr S. (2013). Nitric oxide generated by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae drives plant infection. New Phytol. 197 207–222. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04368.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimana J., Gebhardt K., Höltzel A., Schmid D. G., Süssmuth R., Müller J., et al. (2002). Arylomycins A and B, new biaryl-bridged lipopeptide antibiotics produced by Streptomyces sp. Tü 6075. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and biological activities. J. Antibiot. 55 565–570. 10.7164/antibiotics.55.565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicht M., Kombrink E. (2013). The role of nitric oxide in the interaction of Arabidopsis thaliana with the biotrophic fungi, Golovinomyces orontii and Erysiphe pisi. Front. Plant Sci. 4:351. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlářová M., Petřivalskı M., Piterková J., Luhová L., Kočřov J., Lebeda A. (2011). Influence of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species on development of lettuce downy mildew in Lactuca spp. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 129 267–280. 10.1007/s10658-010-9626-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S., Bhattacharjee A. (2016). Dynamics of protein tyrosine nitration and denitration: a review. J. Proteo. Genomics 1:105 10.15744/2576-7690.1.105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Fitzgerald K. A., Cancro M. P., Marshak-Rothstein A. (2015). Nucleic acid-sensing receptors: rheostats of autoimmunity and autoinflammation. J. Immunol. 195 3507–3512. 10.4049/jimmunol.1500964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood H. S., Galeva N. A., Bartlett R. K., Urbauer R. J., Williams T. D., Urbauer J. L., et al. (2003). Selective nitration of Tyr99 in calmodulin as a marker of cellular conditions of oxidative stress. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 16 95–102. 10.1021/tx025566a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi G., Cappelletti G., Negri A., Pagliato L., Maggioni M. G., Maci R., et al. (2005). Characterization of nitroproteome in neuron-like PC12 cells differentiated with nerve growth factor: identification of two nitration sites in alpha-tubulin. Proteomics 5 2422–2432. 10.1002/pmic.200401208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrion-Gomez J. L., Benito E. P. (2011). Flux of nitric oxide between the necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea and the host plant. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12 606–616. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00695.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandelle E., Delledonne M. (2011). Peroxynitrite formation and function in plants. Plant Sci. 181 534–539. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev V. A., Mikkelsen R. B. (2010). Protein tyrosine nitration in cellular signal transduction pathways. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 30 420–429. 10.3109/10799893.2010.513991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo W. S., Kim Y. J., Kabir M. H., Kang J. W., Ahsan-Ul-Bari M., Kim K. P. (2015). Mass spectrometric analysis of protein tyrosine nitration in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 34 166–183. 10.1002/mas.21429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Lamattina L., Spoel S. H., Loake G. J. (2014). Nitric oxide function in plant biology: a redox cue in deconvolution. New Phytol. 202 1142–1156. 10.1111/nph.12739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Mackrill J. J. (2016). Calcium signaling in Oomycetes: an evolutionary perspective. Front. Physiol. 7:123. 10.3389/fphys.2016.00123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X., Wagener N., McLellan H., Boevink P. C., Hua C., Birch P. R. J., et al. (2018). Phytophthora infestans RXLR effector SFI5 requires association with calmodulin for PTI/MTI suppressing activity. New Phytol. 219 1433–1446. 10.1111/nph.15250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The index of disease development on potato leaves at 9 dpi with avr MP 946 and vr MP 977 P. infestans based on a I–IV point scale, which represents the percentage of leaf area covered by late blight symptoms. Values are means of average disease indexes from 10 leaves from three independent experiments.

Tyrosine nitration pattern of avr MP 946 (A) and vr MP 977 (B) P. infestans growing in vitro and in planta conditions, using 10 mM sodium dithionite as control of anti-nitrotyrosine antibody specificity. Treatment PVDF membranes with sodium dithionite (prior to incubation with the polyclonal antibody against nitrotyrosine diluted at 1:1000) converts nitrotyrosine in aminotyrosine, allowing the detection of false positive spots. Molecular-mass standards (kDa) are indicated on the left.

Amino acid sequence of the identified homologous proteins (matched peptides derived from P. infestans shown in bold red).