Abstract

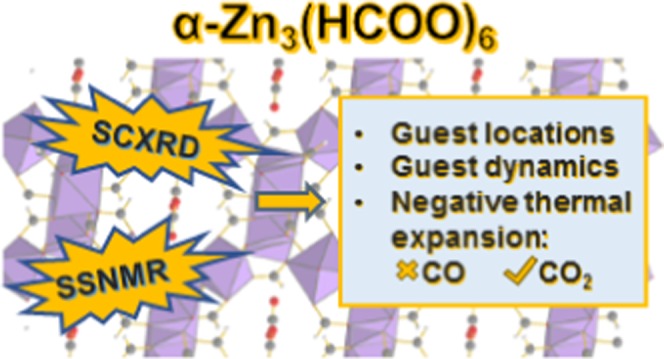

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are promising gas adsorbents. Knowledge of the behavior of gas molecules adsorbed inside MOFs is crucial for advancing MOFs as gas capture materials. However, their behavior is not always well understood. In this work, carbon dioxide (CO2) adsorption in the microporous α-Zn3(HCOO)6 MOF was investigated. The behavior of the CO2 molecules inside the MOF was comprehensively studied by a combination of single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) and multinuclear solid-state magnetic resonance spectroscopy. The locations of CO2 molecules adsorbed inside the channels of the framework were accurately determined using SCXRD, and the framework hydrogens from the formate linkers were found to act as adsorption sites. 67Zn solid-state NMR (SSNMR) results suggest that CO2 adsorption does not significantly affect the metal center environment. Variable-temperature 13C SSNMR experiments were performed to quantitatively examine guest dynamics. The results indicate that CO2 molecules adsorbed inside the MOF channel undergo two types of anisotropic motions: a localized rotation (or wobbling) upon the adsorption site and a twofold hopping between adjacent sites located along the MOF channel. Interestingly, 13C SSNMR spectroscopy targeting adsorbed CO2 reveals negative thermal expansion (NTE) of the framework as the temperature rose past ca. 293 K. A comparative study shows that carbon monoxide (CO) adsorption does not induce framework shrinkage at high temperatures, suggesting that the NTE effect is guest-specific.

Introduction

Gas separation and capture are essential for many industrial processes, such as chemical production, flue gas purification, and natural gas treatment.1 Various separation techniques have been developed. However, these procedures are typically energy intensive,2 motivating research into alternative separation and capture techniques.3−5 Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are crystalline solids with metal-based nodes linked by organic bridges6−8 and are strong candidates among the suggested technologies.3,9−12 MOFs have permanent porosities and large surface areas, making them promising for gas adsorption.3 As a solid adsorbent, MOFs can provide a more energy-efficient approach than conventional chemical absorption methods.9,13 As compared to traditional porous materials such as zeolites, MOFs are more versatile and adaptable as their gas adsorption performance can be optimized by systematically varying the metal centers and organic linkers.9,11,13−15 These promising attributes of MOFs and the pressing need for alternative gas adsorbents have led to a rapid growth in novel MOF synthesis.16,17 Nonetheless, the detailed adsorption behaviors of many MOFs are still unknown.

M3(HCOO)6 (M = Mg, Zn, Mn, Co, Ni, and Fe),18−37 a family of microporous MOFs constructed from formate linkers, has shown great potential as gas capture media. These MOFs are thermally robust (stable up to ca. 400–500 K)18−21,31,35 and can be synthesized using relatively straightforward procedures and inexpensive reagents.36−38 M3(HCOO)6 frameworks are also capable of guest adsorption.19−24,27,33,39−44 For instance, α-Mg3(HCOO)6 has demonstrated remarkable results for carbon dioxide (CO2) capture.27,39,40,42 A 27.4 kJ mol–1 isosteric heat of CO2 adsorption (Qst(CO2)) was measured,27 which is among the highest found for MOFs without open metal sites or basic (i.e., nonacidic) functional groups.45 Selective gas adsorption ability was also reported,27,42,46,47 with preferential adsorption for CO2 over methane and nitrogen gas.27 Although there is abundant knowledge on CO2–α-Mg3(HCOO)6 systems, experimental reports on CO2 adsorption using other M3(HCOO)6 frameworks are relatively scarce and have only been performed for the Mn analogue.22,29,42 Furthermore, CO2 has been the focus of many gas-loaded M3(HCOO)6 studies. However, there is limited information on other gas–M3(HCOO)6 systems. To the best of our knowledge, carbon monoxide (CO) adsorption in M3(HCOO)6 has yet to be studied. Since a complete characterization of gas–MOF systems is crucial for identifying successful gas absorbents, these knowledge gaps must be filled to advance MOF-based gas capture technologies.

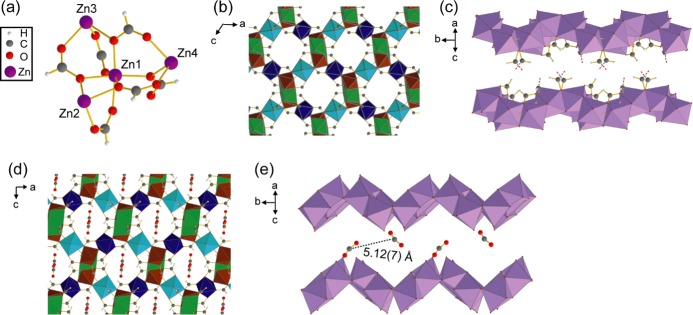

Besides α-Mg3(HCOO)6, α-Zn3(HCOO)6 has also shown promising gas adsorption abilities. α-Zn3(HCOO)6 has the same topology as α-Mg3(HCOO)6 but contains a different metal center. Four crystallographically inequivalent Zn atoms act as metal nodes in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 (Figure 1).21 Each Zn center is fully coordinated to six formate oxygens, resulting in a slightly distorted [ZnO6] octahedron. The extended α-Zn3(HCOO)6 lattice is constructed from chains of edge-sharing [ZnO6] octahedra that are further connected by vertex-sharing [ZnO6] octahedra. This arrangement results in zigzag-shaped porous channels that propagate along the crystallographic b axis. The channel interiors are lined with formate hydrogens and oxygens, which have been shown to act as guest adsorption sites.21,43 Even though α-Zn3(HCOO)6 and α-Mg3(HCOO)6 have the same topology, differences in adsorption behavior can still be expected. Gas affinity differences have been observed between various M3(HCOO)6 frameworks.23,42,43,46 In the case of α-Zn3(HCOO)6 and α-Mg3(HCOO)6, computational investigations have shown that α-Zn3(HCOO)6 binds stronger to acetylene, methane, nitrogen, hydrogen, and CO2 compared to α-Mg3(HCOO)6.46 Similar results were also obtained in a recent methane adsorption study, in which a stronger methane–MOF interaction was detected for α-Zn3(HCOO)6 due to its smaller pore size.43 These studies suggest that α-Zn3(HCOO)6 can be a more efficient gas adsorbent than the Mg analogue due to the structural effects of accommodating the larger metal center. Unfortunately, limited experimental characterization has been conducted on the gas adsorption ability of α-Zn3(HCOO)6. Besides methane,43 its adsorption behavior has only been studied for hydrogen, nitrogen, iodine, and several solvents.21

Figure 1.

(a) Connectivity between the four crystallographically inequivalent Zn centers in α-Zn3(HCOO)6. (b) Extended crystal structure of α-Zn3(HCOO)6, as viewed along the crystallographic b axis. Framework hydrogens are omitted for clarity. (c) Porous channel of α-Zn3(HCOO)6, as viewed perpendicular to the crystallographic b axis. The [ZnO6] units connecting the top and bottom of the channel are omitted for clarity. The C–O bonds between the omitted [ZnO6] units and the linker carbons are shown as red and gray dashed lines. (d) Extended crystal structure of CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6, as viewed along the crystallographic b axis. (e) MOF channel as viewed perpendicular to the crystallographic b axis, showing the adsorbed CO2 locations and the distance between neighboring CO2. Distance error is given in parentheses. Hydrogens, framework carbons, and [ZnO6] units that connect the top and bottom of the channel are omitted. In all figures, carbon atoms are gray, oxygen atoms are red, hydrogen atoms are white, and zinc atoms are purple. Octahedra represent [ZnO6] units in (b)–(d), with different colors signifying [ZnO6] with crystallographically distinct Zn atoms in (b) and (d).

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) is commonly employed to characterize the structure of guest-loaded MOFs.48−51 SCXRD probes the long-range crystal structure and can provide information on framework connectivity and geometries with atomic resolution. In ideal cases, SCXRD can also accurately locate the guest molecules, identify the guest binding sites, and determine the site occupancies. SCXRD has been widely employed in MOF characterization to study gas adsorption52−55 and monitor framework structural transformations.56−58 Even though SCXRD is a powerful structural characterization method, MOF single crystals of suitable size and quality can be difficult to obtain. Furthermore, detailed guest dynamics studies can be challenging to conduct since SCXRD experiments only provide time-averaged structural data and are commonly performed at cryogenic temperatures that restrict or immobilize guests. In these cases, the pairing of SCXRD with solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (SSNMR) spectroscopy can provide fruitful results. SSNMR spectroscopy probes short-range ordering and local structure. It can provide insights into host–guest interactions59−61 and guest dynamics.41,62−70 Both metal– and linker–guest interactions can be directly examined using SSNMR,39,66,67,71,72 allowing for the main adsorptive interactions to be identified. Moreover, molecular motion can alter the SSNMR spectral appearance in a predictable manner due to the anisotropic nature of most NMR interactions. Therefore, motional information (i.e., the types of motions and the parameters defining the motions) can be obtained from variable-temperature (VT) SSNMR experiments via spectral simulations.73 With knowledge of the crystal structure, a detailed motional model can be developed for guests within MOF frameworks.41,63−67,70 Thus, the combination of SSNMR spectroscopy and SCXRD can provide a complete picture of guest behavior inside MOFs.

Here, we studied CO2 and CO adsorption within α-Zn3(HCOO)6. The guest binding sites and adsorption mechanism were identified by SCXRD. Static VT 13C SSNMR spectroscopy was employed to examine the guest dynamics, and a motional model was developed for the adsorbed guests. Unexpected trends in the chemical shift (CS) tensor parameters and motional parameters as a function of temperature were observed during our CO2 study, indicating the negative thermal expansion (NTE) of the framework. The presence of NTE was also supported by 1H → 13C cross-polarization (CP) NMR experiments. Lastly, we compared the dynamics of CO2 adsorbed in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 to those adsorbed in similar MOFs.

Results and Discussion

Behavior of CO2 Adsorbed in α-Zn3(HCOO)6

To determine the number and location of guest adsorption sites in α-Zn3(HCOO)6, we have solved the crystal structure of CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 using SCXRD (Figure 1). CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 crystallizes in the monoclinic system (space group P21/n) with unit cell parameters a = 11.326(2) Å, b = 9.821(1) Å, c = 14.441(2) Å, and β = 91.297(5)°. The crystallographic data are summarized in Tables S1–S7. Like the empty MOF, the CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 has four crystallographically inequivalent Zn atoms sitting in the center of slightly distorted [ZnO6] octahedra. Similar to the activated α-Zn3(HCOO)6, the framework contains the chains of edge-sharing [ZnO6] connected by vertex-sharing [ZnO6], with porous channels running along the crystallographic b axis. The CO2 guests were found near the walls of the porous channels, forming zigzag CO2 chains with neighboring CO2 ca. 5 Å apart. The CO2 molecules sitting at the top of the zigzag array are crystallographically equivalent to those at the bottom of the array. Thus, α-Zn3(HCOO)6 contains only one distinct CO2 adsorption site. The guests also display relatively large and anisotropic ellipsoids at 120 K (Figures 2 and S1). The thermal ellipsoids extend toward the adjacent CO2, suggesting that the adsorbed CO2 molecules move between neighboring adsorption sites even at 120 K.

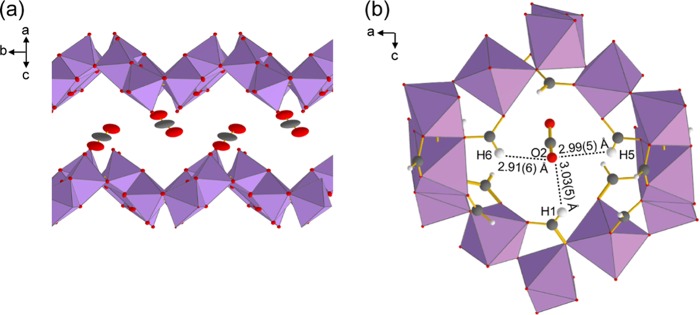

Figure 2.

(a) CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 MOF channel with atoms appearing as thermal ellipsoids. The ellipsoids are at the 50% probability level. Hydrogens, framework carbons, and [ZnO6] units connecting the top and bottom of the channel are omitted for clarity. (b) Local pore structure of CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6. One of the CO2 oxygens (O2) points toward the three formate hydrogens (H1, H5, and H6) that extend into the channel. Carbons are dark gray, oxygens are red, hydrogens are white, and [ZnO6] units are purple octahedra.

Insights into the host–guest interaction were also obtained via SCXRD. First, the [ZnO6] octahedra in the CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 and the empty framework have equivalent O–Zn–O angles and Zn–O distances (Table S8). Therefore, CO2 adsorption does not alter the immediate environment of the Zn centers, and the adsorbed CO2 molecules clearly do not interact with the Zn. This result is confirmed by 67Zn SSNMR spectroscopy (Figures S2 and S3), and a detailed discussion on the 67Zn SSNMR data is given in the Supporting Information. Moreover, the adsorbed CO2 are located close to the framework hydrogens (Hframework), with one of its oxygens (O2) pointing toward the three Hframework (H1, H5, and H6) that extend into the channel (Figure 2). The O2···Hframework distances range from 2.91 to 3.03 Å, which are noticeably shorter than those between CO2 and other framework atoms (Figure S4). Although the crystal structure of α-Mg3(HCOO)6 loaded with CO2 has not been reported, computational studies have shown that CO2 in α-Mg3(HCOO)6 are also located near the Hframework.39,46 The adsorption is driven by Hframework···O=C=O interactions, and the O···Hframework distance was calculated to be ca. 3.2 Å.39 Since the O2···Hframework distances for CO2 in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 are also close to 3.2 Å, this suggests that Hframework···O=C=O interactions are also responsible for CO2 adsorption in α-Zn3(HCOO)6. Weak hydrogen bonds have been reported as the main host–guest interaction for other guests (e.g., tetrahydrofuran, acetonitrile, acetone) in α-Zn3(HCOO)6, with hydrogen bond acceptors primarily interacting with the Hframework.21

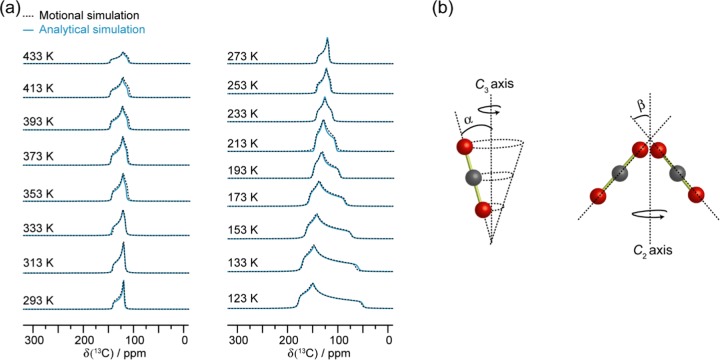

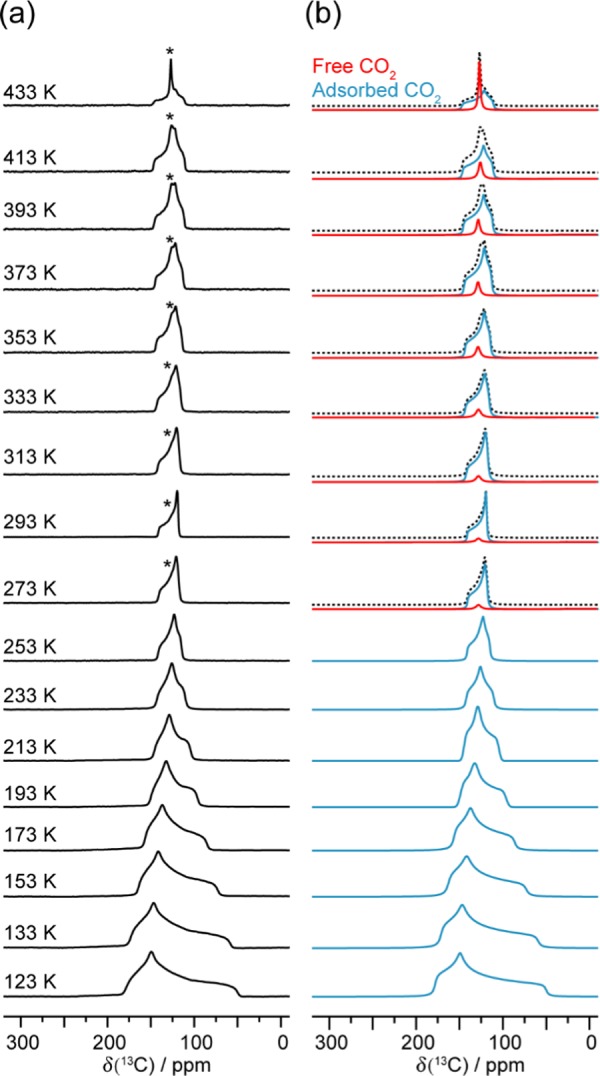

Static VT 13C SSNMR experiments were conducted from 123 to 433 K on CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 to investigate CO2 motions, and the spectra are shown in Figure 3. Since isotopically labeled 13CO2 gas was used, only CO2 signals will contribute significantly to the spectra. A narrow resonance at ca. 126 ppm was found from 273 to 433 K and is attributed to unbound CO2. This assignment is consistent with the 132 ppm isotropic chemical shift (δiso) value previously reported for free CO2.74 A 13C powder pattern was also observed at each temperature, which is ascribed to CO2 bound to the framework. The observation of a single powder pattern indicates the presence of one unique adsorption site, consistent with the SCXRD results.

Figure 3.

(a) Experimental static VT 13C SSNMR spectra of 13CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 recorded from 123 to 433 K at 9.4 T, and (b) the corresponding analytical simulations. Asterisk (*) denotes the unbound CO2 resonance. The spectra simulated from 273 to 433 K are given as summations (dotted black trace) of the adsorbed (solid blue trace) and free (solid red trace) CO2 signals. The 13C CS tensor parameters obtained from the analytical simulations are provided in Table S10.

The VT 13C spectra were analytically simulated (Figure 3), and the apparent 13C CS tensor parameters obtained for adsorbed CO2 are provided in Table S10. Compared to the CS tensor span (Ω) of rigid CO2 (335 ppm),74 the recorded Ω values of CO2 in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 are consistently smaller (ca. 128–36 ppm from 123 to 433 K). In agreement with the large CO2 thermal ellipsoids obtained from SCXRD, the smaller Ω implies that the CO2 still displays motions despite being confined in the framework. This is further supported by the dependence of Ω and skew (κ) on temperature. The motional behavior of CO2 in MOFs has been well documented, and the static 13C SSNMR line shapes of CO2 have been consistently observed to vary with temperature.39,63,64,66−70,75 The Ω and/or κ generally exhibit unidirectional change with temperature. For example, the Ω usually decreases with increasing temperature due to the increased mobility of CO2 at higher temperatures.66,67,70,75 However, this is not the case for CO2 in α-Zn3(HCOO)6. In the temperature range of 123–293 K, the Ω indeed decreases monotonically with increasing temperature as expected (Table S10 and Figure S5). The trend is reversed in the high-temperature range of 293–433 K. Above 293 K, instead of decrease, the Ω increases slightly with increasing temperature. A larger Ω is typically associated with decreased CO2 mobility.66 The temperature dependence of Ω from 293 to 433 K suggests that within this temperature range, the degree of CO2 motion decreases with increasing temperature. The κ also exhibits a similar trend. We attribute the observed peculiar temperature dependencies of Ω and κ of 13CO2 adsorbed in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 to the NTE of the MOF at temperatures above 293 K as the slight shrinkage of the framework resulting from the NTE can lead to a more confined CO2 with reduced mobility. Even though the NTE has yet to be reported for α-Zn3(HCOO)6, it has been observed in other Zn formate MOFs.76,77 For instance, the Zn octahedra and formate linkers of Zn(HCOO)2·2(H2O) distort upon heating.76 This results in a “hinge-strut”-like framework motion and an anisotropic thermal expansion of the framework with NTE along the crystallographic c axis (i.e., the unit cell shrinks along the c axis as temperature increases). Similar observations were reported for the [CH3NH3][Zn(HCOO)3] and [C(NH2)3][Zn(HCOO)3] frameworks, which displayed moderate NTE along the c axis when the temperature was raised from 110 to 300 K.77

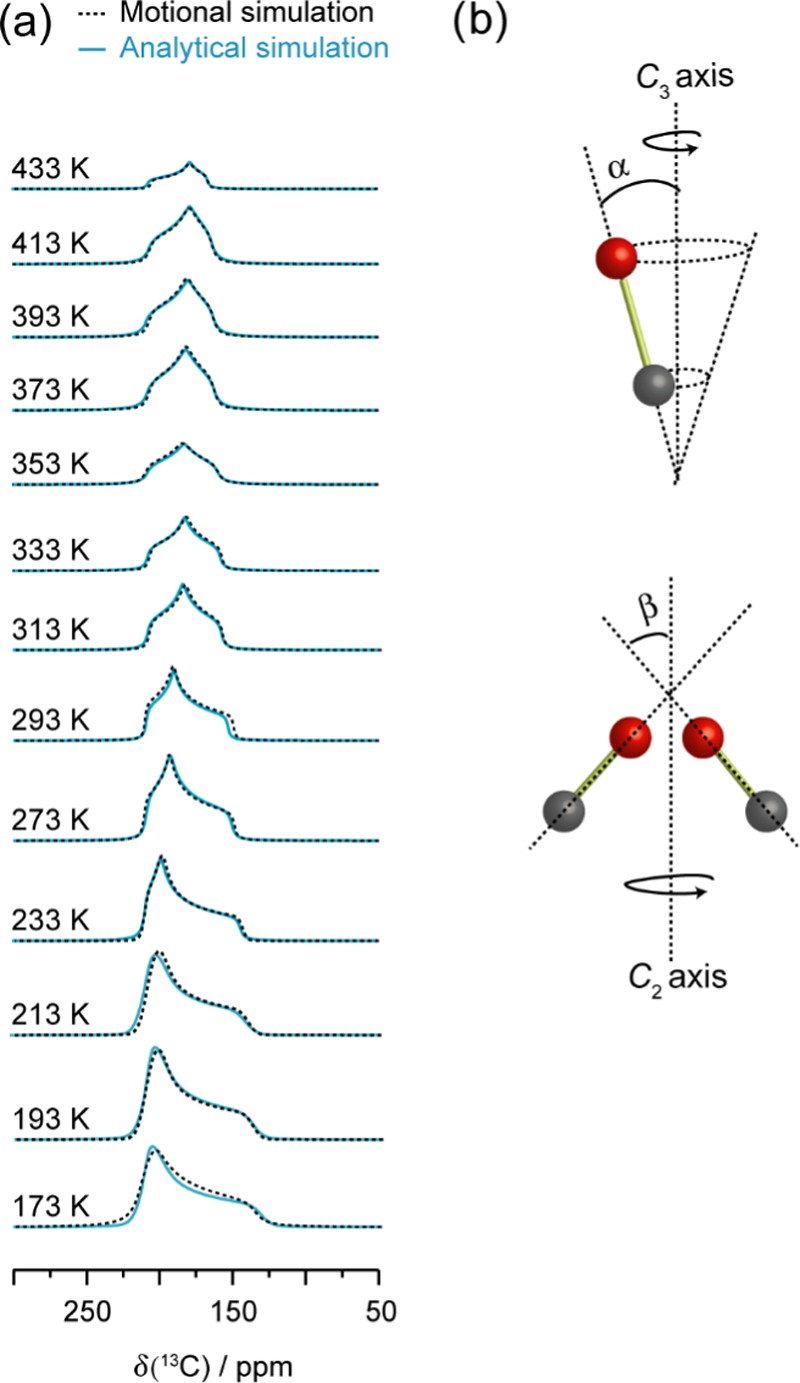

To further examine the CO2 dynamics, 13C SSNMR line shapes for CO2 undergoing molecular motions were modeled via motional simulations (Figure 4). Information on the motional types (e.g., wobbling, hopping, swinging, etc.) with their associated angles and rates can be acquired from these simulations.78 Spectra generated using a threefold (C3) rotation (as described by the angle α) and a twofold (C2) jump (as governed by the angle β) provided an excellent agreement with the experimental spectra. Both motions occur at rates that are on the order of magnitude of ca. ≥107 Hz, which is fast on the NMR time scale given that the breadth of the powder pattern of rigid CO2 is on the order of 104 Hz at 9.4 T.74 Additional simulation results provided in the Supporting Information (Figure S9) clearly suggest that the observed changes in experimental spectra as a function of temperature are due to the change in the motional angles rather than motional rates.

Figure 4.

(a) Motional simulations of the adsorbed CO2 resonance (dotted black trace), and the corresponding analytical simulation (solid blue trace) acquired by fitting the VT 13C SSNMR spectra (Figure 3). The motional simulations were constructed using a C3 rotation (b, left) and a C2 jump (b, right) for the CO2 dynamics. The angles α and β govern these two motions, and the corresponding values are provided in Table S10. Both motions occur at rates on the order of magnitude of ca. ≥107 Hz in the studied temperature range.

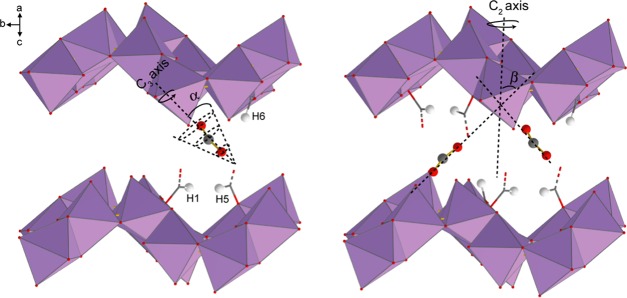

Since SCXRD suggests that the CO2 is adsorbed at the framework hydrogen, the SSNMR data thus indicate that the CO2 undergoes a local rotation (or “wobbling”) modeled by a C3 rotation and a nonlocalized C2 jump between two neighboring framework hydrogens pointing toward the center of the channel (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Illustration of the (left) wobbling and (right) hopping motions displayed by CO2 adsorbed in α-Zn3(HCOO)6. The CO2 wobbles locally upon the hydrogen-based adsorption site through the angle α and hops between adjacent adsorption sites located along the crystallographic b axis at an angle β. Carbons are dark gray, oxygens are red, hydrogens are white, and [ZnO6] units are purple octahedra. All framework carbons and hydrogens are omitted for clarity except for H1, H5, and H6 and the corresponding carbons. The red and gray dashed lines represent C–O bonds between the carbons and [ZnO6] units that connect the top and the bottom of the channels. These units are also omitted for clarity.

The angles (α and β) defining the C3 and C2 motions also change with temperature (Table S10), whereas the motional rates remain the same across the experimental temperature range (see the Supporting Information for a more detailed discussion on the motional rates). The temperature dependencies of the motional angles are consistent with the dynamic model described above. For example, α, the angle describing the amplitude of the local (C3) rotation, gradually climbs from 37.0 to 49.5° when the temperature is raised from 123 to 293 K. Such change is expected as an increase in temperature should result in an increase in the amplitude of the local rotation. However, CO2 displayed a decrease in wobbling and hopping at temperatures higher than 293 K. Between 293 and 443 K, α declined slightly from 49.5 to 47.5°. This is consistent with the proposed NTE effect, which results in a more restricted CO2 wobbling at higher temperatures. The angle β describing the alignment of CO2 with respect to the channel also dropped from 47.0 to 40.0° in this temperature range.

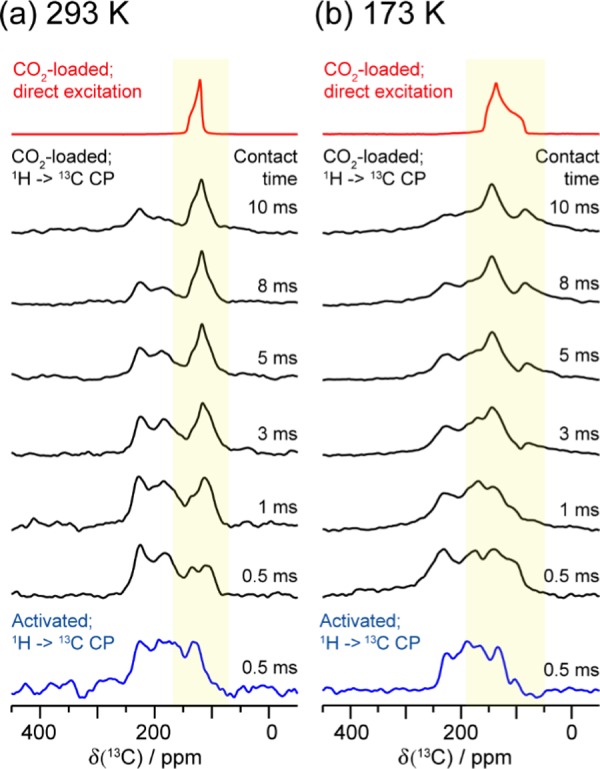

1H → 13C CP SSNMR experiments were also performed to investigate the adsorptive behavior of CO2 loaded in the α-Zn3(HCOO)6 framework. The CP spectra were acquired at two temperatures, 173 and 293 K, using various CP contact times (Figure 6). In 1H → 13C CP experiments, polarization is transferred from 1H nuclei to neighboring 13C nuclei.79 The polarization transfer is mediated by heteronuclear dipolar interactions, which is sensitive to 1H–13C internuclear distances as well as molecular mobility. As a result, stationary 13C nuclei that are in very close proximity to protons will give strong CP signals at short contact times. Mobile 13C nuclei and/or 13C nuclei that are far away from protons will require long contact times to be detected or might not be detectable at all by CP experiments.

Figure 6.

Static 13C SSNMR spectra of 13CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 recorded using direct excitation (red traces) and 1H → 13C CP (black traces) at (a) 293 and (b) 173 K. The 1H → CP SSNMR spectra were obtained using various CP contact times (0.5–10 ms). The location of the adsorbed 13CO2 resonance deduced from the direct-excitation spectrum is highlighted with a yellow box. The 1H → 13C CP spectra of the activated framework are also provided for reference (blue traces, CP contact time = 0.5 ms). All spectra were acquired at 9.4 T.

When a short contact time of 0.5 ms was employed, the CP spectra of both empty and CO2-loaded MOFs are dominated by the 13C signals from the organic linkers in the framework (Figure 6). This observation is not unexpected since the framework carbons in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 are covalently bonded to the hydrogens; therefore, the framework 13C in the H–COO– fragment can give observable CP signals despite being at natural abundance. At any given temperature, the CP signal due to 13CO2 adsorbed in the MOF was detected at longer CP contact times (i.e., 1–10 ms), with the CP intensity increasing with contact time. This is because the 1H–13C dipolar interaction between the adsorbed 13CO2 and framework hydrogens is relatively weak due to the long distances between the 13CO2 and the linker hydrogens, and the interaction is further attenuated by the anisotropic CO2 motions. As a result, a longer contact time is needed for polarization transfer.

Normally, the CP signals for 13CO2 adsorbed inside MOFs are weaker at higher temperatures than those at lower temperatures due to an increase in CO2 mobility.39,66 Interestingly, the opposite is observed in the present case: the CP signal due to the 13CO2 adsorbed in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 is more intense at 293 K than at 173 K at any given contact time, indicating that the 1H–13C dipolar interaction between adsorbed 13CO2 and framework hydrogens is slightly stronger at higher temperatures. This result is consistent with the proposed NTE effect as a slight contraction of the framework at higher temperatures will result in a slight reduction in the distances between the framework hydrogens and 13CO2, leading to a stronger CP intensity. Thus, the 1H → 13C CP experiments not only are consistent with the fact that the CO2 adsorption sites are the framework hydrogens, but also support the proposed NTE.

CO Adsorption and Dynamics in α-Zn3(HCOO)6

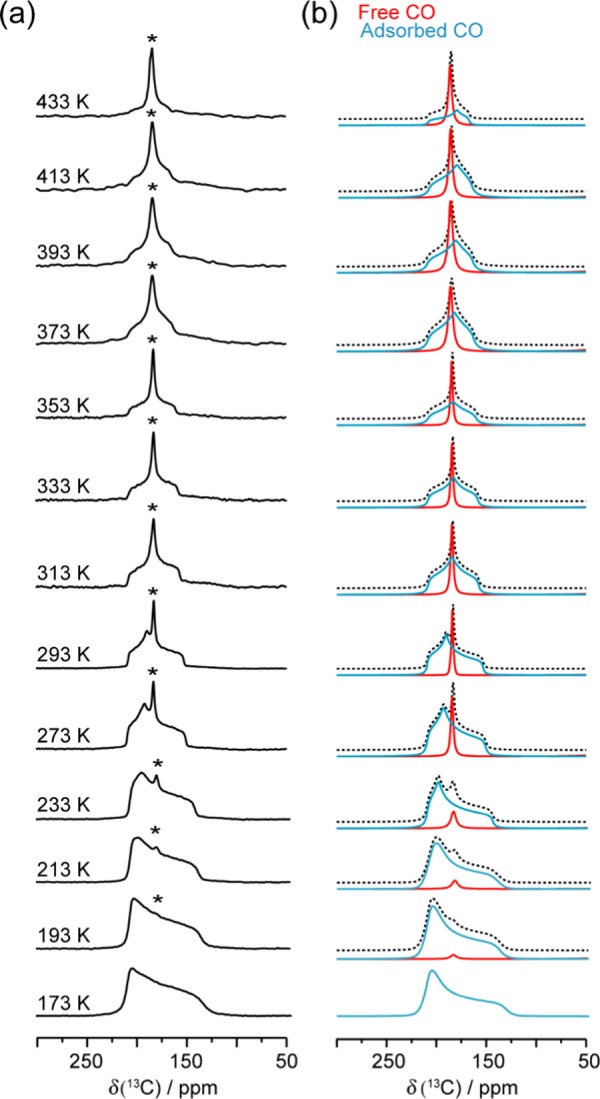

To examine if the NTE phenomenon observed in the CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 framework is guest dependent, carbon monoxide (CO) adsorption in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 was studied via static VT 13C SSNMR spectroscopy. Experiments were performed from 173 to 433 K to encompass the starting point of the NTE observed for CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6, and the spectra are shown in Figure 7. A single powder pattern corresponding to adsorbed CO was detected within the temperature range of 193–433 K, along with a sharp isotropic peak corresponding to unbound CO (δiso = ca. 184 ppm). The changes in the line shape and breadth of the broad powder patterns indicate that the CO molecules experience molecular motions inside the MOF. The apparent 13C CS tensor parameters were extracted from spectral simulations, and the tensor parameters are temperature-dependent (Table S11). The apparent Ω varies from 77 to 41 ppm in the studied temperature range, which is drastically smaller than the Ω of rigid CO (353 ppm).74 Moreover, the Ω and κ of CO have a different temperature dependence compared to those of CO2: the Ω and κ of CO adsorbed inside the MOF exhibit a monotonic decrease with increasing temperature (Figure 8). Since the kinetic diameter of CO (3.76 Å)80 is larger than that of CO2 (3.30 Å)80 and closer to the pore size of α-Zn3(HCOO)6 (dpore = 4.44 Å),46 the chemical shift anisotropy powder pattern of CO should be more sensitive to framework contraction that leads to reduced CO mobility. The fact that the apparent Ω of CO only unidirectionally decreases with increasing temperature in the entire temperature range of 173–433 K implies that the α-Zn3(HCOO)6 framework does not exhibit NTE at high temperatures when CO is the guest molecule. Guest molecules have also influenced the thermal expansion behavior of other metal formate frameworks.77,81 For instance, the size of the cations in the [AmineH+][Mn(HCOO)3] MOFs (AmineH+ = [(CH2)3NH2]+ and [(NH2)3C]+)77 and their hydrogen bonding strength with the host framework81 can both affect the expansion magnitude. In the case of CO- and CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6, our 13C SSNMR results suggest that NTE only occurs for the CO2-loaded MOF in the studied temperature range.

Figure 7.

(a) Experimental static VT 13C SSNMR spectra of 13CO in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 obtained from 173 to 433 K (Bo = 9.4 T), and (b) the corresponding analytical simulations. Free CO resonances are marked with asterisks (*). The analytical simulations acquired from 193 to 433 K are given as summation spectra (dotted black trace) constructed from the free (solid red trace) and adsorbed (solid blue trace) CO resonances. The 13C CS tensor parameters obtained from the simulations can be found in Table S11.

Figure 8.

Comparison between the apparent (a) Ω(13C) and (b) κ(13C) of CO2 (open red circles) and CO (solid black squares) in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 at various temperatures. The vertical dashed line marks the temperature (ca. 293 K) where the Ω and κ trends begin to reverse for CO2. The Ω and κ values were obtained from analytical simulations as shown in Figures 3 and 7. The measured values can be found in Tables S10 and S11.

To obtain additional information on the behavior of CO in the MOF, motional simulations were also performed on the 13CO SSNMR line shapes, and the results are provided in Figure 9. The adsorbed CO molecules were found to simultaneously undergo a C3 rotation and a C2 jump, which are described by the angles α and β, respectively (Figure 9). These motions occur in the fast motion regime (ca. on the order of magnitude of ≥107 Hz) and are analogous to those exhibited by CO2. Since CO and CO2 generally have the same adsorption sites in MOFs82−87 and CO can also act as a hydrogen bond acceptor,87−91 CO in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 is likely adsorbed at the hydrogen of the formate linker. 67Zn SSNMR experiments were also conducted, and CO adsorption was found to have no significant influence on the immediate Zn environments (Figure S2). Thus, the C3 rotation corresponds to a localized wobbling upon the hydrogen-based adsorption site, and the C2 jump describes hopping between adjacent adsorption sites located along the channel (Figure S6). Previous computational studies showed that both the carbon and oxygen of CO are capable of hydrogen bonding, but a stronger interaction was observed for C···H as compared to O···H.88,89 Therefore, CO likely interacts with the hydrogens of α-Zn3(HCOO)6 via the carbon atom. Consistent with the apparent 13C CS parameters, motional simulation results also revealed unidirectional trends in α and β as a function of temperature. α increased from 45.0 to 47.5° and β climbed from 20.0 to 39.5° when the temperature was raised from 173 to 433 K (Table S11 and Figure S7), indicating a lack of NTE for the CO-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 framework.

Figure 9.

(a) Motional simulations of the CO resonance (dotted black trace) recorded from 173 to 433 K in α-Zn3(HCOO)6. The corresponding analytical simulation (solid blue trace) from Figure 7 is also provided for comparison. The motional simulation was obtained using a (b) C3 rotation and C2 jump. The motional parameters obtained from the simulation are provided in Table S11.

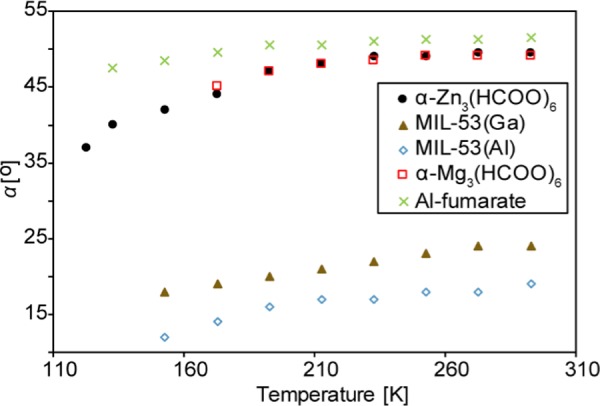

Comparison of CO2 Dynamics in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 and Other MOFs with Hydrogen-Based Adsorption Sites

In recent years, we have examined CO2 dynamics in three types of MOFs where the CO2 molecules are adsorbed at the framework hydrogen atoms: (i) MIL-53 (M), M = Al, Ga;66 (ii) α-Mg3(HCOO)6;39 and (iii) Al-fumarate.67 In (i) and (iii), the CO2 molecules are adsorbed at the hydrogens of the bridging hydroxyl groups, whereas in (ii) the CO2 molecules are adsorbed at the hydrogens of the formate linkers. The common motion experienced by CO2 in these types of MOFs is the local rotation or wobbling motion. As mentioned earlier, this motion involves the CO2 molecule adsorbed at the framework hydrogen wobbling through an angle α between the longitudinal axis of CO2 and the wobbling axis (Figure 5). Since α defines the space that CO2 sweeps through during the rotation, it may be related to the strength of the interaction between CO2 and hydrogen.40,66 Thus, a stronger O=C=O···H interaction can result in a smaller wobbling angle. Figure 10 and Table 1 show that the α of CO2 adsorbed in the MIL-53-based MOFs are remarkably smaller than those in the formate-based MOFs. This suggests that the hydrogens in the OH groups of MIL-53 have a stronger acidity compared to the hydrogens in the H–COO– fragments of α-M3(HCOO)6, resulting in a stronger interaction with CO2. For MIL-53, the α of CO2 in MIL-53 (Al) is consistently smaller than that in MIL-53 (Ga) at any given temperature, indicating that the nature of the metal center plays a role in host–guest interaction.66 However, the situation in α-M3(HCOO)6 is different. The α of CO2 in Zn- and Mg-formate are very similar, implying that the metal does not affect the CO2 motion in a significant way. The α of CO2 in Al-fumarate MOF is the largest among the MOFs discussed here. Since Al-fumarate and MIL-53 (Al) have the same framework topology and metal center, the large difference in the degree of local rotation obviously results from the nature of the organic linker.

Figure 10.

Wobbling angles (α) of CO2 adsorbed in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 (solid black circles), α-Mg3(HCOO)6 (open red squares), MIL-53 (Ga) (solid brown triangles), MIL-53 (Al) (open blue diamonds), and Al-fumarate (green crosses) at various temperatures. The numerical values are also provided in Table 1. The α-Zn3(HCOO)6 data was obtained from motional simulations (Figure 4). The α-Mg3(HCOO)6, MIL-53, and Al-fumarate data were acquired from refs (39, 66), and (67), respectively.

Table 1. Wobbling Angles (α) of CO2 Adsorbed in α-Zn3(HCOO)6, α-Mg3(HCOO)6, MIL-53 (Al), MIL-53 (Ga), and Al-Fumarate at Different Temperatures.

| α

(deg) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| temperature (K) | α-Zn3(HCOO)6 | α-Mg3(HCOO)6a | MIL-53 (Al)b | MIL-53 (Ga)b | Al-fumaratec |

| 273 | 49.5 ± 0.5 | 49.0 ± 0.1 | 21.0 ± 0.5 | 24.0 ± 0.5 | 51.3 ± 0.2 |

| 253 | 49.0 ± 0.5 | 49.0 ± 0.1 | 20.0 ± 0.5 | 23.0 ± 0.5 | 51.3 ± 0.2 |

| 233 | 49.0 ± 0.5 | 48.5 ± 0.1 | 19.0 ± 0.5 | 22.0 ± 0.5 | 51.0 ± 0.2 |

| 213 | 48.0 ± 0.5 | 48.0 ± 0.1 | 19.0 ± 0.5 | 21.0 ± 0.5 | 50.5 ± 0.2 |

| 193 | 47.0 ± 0.5 | 47.0 ± 0.1 | 18.0 ± 0.5 | 20.0 ± 0.5 | 50.5 ± 0.2 |

| 173 | 44.0 ± 0.5 | 45.0 ± 0.1 | 17.0 ± 0.5 | 19.0 ± 0.5 | 49.5 ± 0.2 |

| 153 | 42.0 ± 0.5 | 16.0 ± 0.5 | 18.0 ± 0.5 | 48.5 ± 0.2 | |

| 133 | 40.0 ± 0.5 | 47.5 ± 0.2 | |||

| 123 | 37.0 ± 0.5 | ||||

Conclusions

CO2 adsorption in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 MOF was characterized comprehensively by SCXRD and SSNMR, and insights into the behavior of CO2 and its influence on the MOF framework were attained. Using SCXRD, the positions of the CO2 molecules inside the MOF channel were accurately determined, and the framework hydrogens act as adsorption sites. Static VT 13C SSNMR results reveal that the CO2 molecules undergo anisotropic motions upon adsorption. Two types of motions were observed via spectral simulations: a localized wobbling upon the hydrogen-based adsorption site and a twofold hopping between adjacent sites located along the porous MOF channel. The dynamic behavior of CO2 in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 was compared with that of other related MOFs where CO2 is also adsorbed at the framework hydrogen. Furthermore, the SSNMR results indicate that CO2 adsorption leads to the NTE of the α-Zn3(HCOO)6 framework at temperatures ≥293 K. However, this NTE phenomenon was not observed in CO-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6, implying that the adsorption-induced NTE is guest-dependent. Thus, the thermal behavior of guest-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 can potentially be employed as an alternative strategy to tune its gas adsorption properties.

Methods

Sample Preparation

α-Zn3(HCOO)6 was synthesized based on a previously reported procedure with minor modifications.21 Briefly, a solution containing 25.0 mL of methanol (MeOH, Fisher Chemical, 99.8%), 1.6 mL of formic acid (Alfa Aesar, 97%), and 4.2 mL of trimethylamine (EMD Millipore Corporation, 99.5%) was added dropwise into a glass jar containing 25 mL of MeOH and 3.0 g of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (BDH Laboratory Supplies, 98%). The jar was then sealed with parafilm and small holes were created to allow for slow evaporation of the MeOH at room temperature. Colorless, transparent crystals were obtained after 3 days. The crystals were separated by vacuum filtration, and five methanol washes were performed.

For the SSNMR and powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) studies, the MOF was activated by placing ca. 0.15 g of the as-made sample, which was ground into a fine powder, into the bottom of an L-shaped glass tube. The glass tube was then attached to a Schlenk line and heated to 353 K for 18 h under dynamic vacuum (≤1 mbar), resulting in the “activated” MOF. The activated sample was then loaded with 13CO2 (Sigma-Aldrich, 99% 13C isotope enriched) and/or 13CO (Sigma-Aldrich, 99% 13C isotope enriched) gas. This was accomplished by first introducing a known amount of the gas into the Schlenk line and then freezing the gas in the MOF by submerging the glass tube in liquid nitrogen. A flame-sealing procedure was then performed to remove the glass tube from the vacuum line. The gas loading level used in this study is expressed by a molar ratio of guest molecules to Zn. A loading level of 0.1 guest molecule/Zn was employed for all the 13CO2 and low-temperature (T = 173–293 K) 13CO experiments. A loading level of 0.075 13CO/Zn was employed for the high-temperature (T = 313–433 K) experiments to minimize the intensity of the free CO SSNMR signal. The 13CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 sample employed for SCXRD analysis was prepared based on the same activation and gas adsorption procedure outlined above. However, no grinding was performed, and the activated MOF was saturated with CO2.

PXRD was performed on the as-made and activated α-Zn3(HCOO)6, and good agreement was obtained between the experimental and calculated powder patterns (Figure S8).

X-ray Diffraction

SCXRD analysis was performed at 120 K using a Bruker-Nonius KappaCCD Apex2 diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). The sample was mounted on a MiTeGen polyimide micromount with a small amount of Paratone-N oil. A symmetry constrained fit of 9044 reflections with 6.12° < 2θ < 135.18° was employed to determine the unit cell dimensions. SAINT92 was used for frame integration. The raw data was then scaled and adsorption corrected via a multiscan averaging of symmetry-equivalent data using SADABS.93

PXRD patterns were obtained using a Rigaku diffractometer with Co Kα radiation (λ = 1.7902 Å). 2θ values were set to range from 5 to 45° with an increment of 0.02° and a scanning rate of 10° min–1.

13C SSNMR Spectroscopy

All 13C SSNMR experiments were performed using a Varian Infinity Plus spectrometry at 9.4 T (Oxford wide-bore magnet; νo(13C) = 100.5 MHz) equipped with a 5 mm HX Varian/Chemagnetics static probe. Chemical shifts were externally referenced using the methylene carbon signal from ethanol.

For the VT experiments, temperature calibration was performed using the 207Pb chemical shift of Pb(NO3)2.9494 An error of ±2 K is associated with the temperatures. A Varian VT temperature unit was employed. The spectra were obtained using a DEPTH-echo pulse sequence with continuous wave proton decoupling to suppress the probe background signal.66,95 An interpulse delay of 40 μs was used for all experiments, and the recorded FID were left-shifted to the echo maxima. For the CO2-loaded samples, spectra were recorded from 123 to 433 K. A π/2 pulse length of 2.35 μs was employed. Apart from the spectrum recorded at 293 K, which consists of 46 656 scans, ca. 1024 scans were executed for each spectrum. A recycle delay of 3 s was used for acquisitions at temperatures between 173 and 353 K, and the delay was set to 5 s for all other temperatures. For the CO-loaded samples, spectra were recorded from 173 to 433 K. The π/2 pulse length was set to 3.30 μs. To obtain a suitable signal-to-noise ratio, ca. 1000–4600 scans were collected for each spectrum. A recycle delay of 5 s was used for spectra acquired at 273–353 K, whereas a delay of 7 s was employed for all other temperatures.

Two types of simulation were performed on the static VT 13C SSNMR spectra: analytical simulations and motional simulations. Analytical simulations were conducted to extract the apparent 13C CS tensor parameters. WSolids96 was employed for the analytical simulations. Motional simulations were performed to quantitatively examine the guest dynamics. These simulations were executed using EXPRESS,73 which simulates the effect of Markovian jump dynamics on SSNMR line shapes. The EXPRESS73 simulations were performed at 9.4 T using the 13C NMR parameters of rigid CO2 and CO,74 separately, as input parameters. Powder averaging was carried out using 2000 powder increments and the ZCW method. The spectral width was set to 100 kHz, and 2k points were used in the FID. The motional types, rates, and angles were systematically altered until agreement was reached between the simulated and experimental spectra.

The 1H → 13C CP experiments were performed with continuous wave proton decoupling and echo acquisition (i.e., τ1–π–τ2–acq). Spectra were recorded at 173 and 293 K, and the contact times were set to 0.5, 1, 3, 5, 8, and 10 ms. A π/2 pulse length of 2.85 μs was used for the empty, activated MOF, whereas a π/2 pulse length of 3.55 μs was executed for the gas-loaded samples. A recycle delay of 1 s and an interpulse delay (τ1) of 40 μs were used for all experiments. The spectra were obtained using ca. 3600–5560 scans. The recorded FID were left-shifted to the echo maxima.

Acknowledgments

Y.H. thanks the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada for a Discovery grant. Access to the 21.1 T NMR spectrometer, along with CASTEP software and computational hardware, was provided by the National Ultrahigh-Field NMR Facility for Solids (Ottawa, Canada), a national research facility funded by a consortium of Canadian Universities, supported by the National Research Council Canada and Bruker BioSpin and managed by the University of Ottawa (http://nmr900.ca).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b03623.

SCXRD data for CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 at 120 K (Tables S1–S7); comparison between the [ZnO6] octahedra geometries in activated and CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 (Table S8); Oak Ridge thermal ellipsoid plot drawing of the asymmetric unit of CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 (Figure S1); 67Zn SSNMR procedures; 67Zn SSNMR results and discussion; 67Zn SSNMR spectra of CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 (Figures S2 and S3); calculated 67Zn NMR parameters for the Zn centers in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 (Table S9); local pore structure of CO2-loaded α-Zn3(HCOO)6 (Figure S4); apparent 13C CS tensor parameters and motional angles of CO2 adsorbed in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 at 123–433 K (Table S10); apparent 13C tensor parameters and motional angles of CO adsorbed in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 at various temperatures (Table S11); 13C CS tensor parameters and motional angles of CO2 in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 plotted as a function of temperature (Figure S5); illustration of the wobbling and hopping motions of CO in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 (Figure S6); motional angles of CO and CO2 in α-Zn3(HCOO)6 plotted as a function of temperature (Figure S7); experimental and simulated PXRD patterns of as-made and activated α-Zn3(HCOO)6 (Figure S8); discussion on the influence of temperature on the motional rates of CO2 in α-Zn3(HCOO)6; static 13CO2 SSNMR spectra simulated using different motional rates (Figure S9) (PDF)

Crystallographic data (CIF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Rousseau R. W., Ed.; Handbook of Separation Process Technology; Wiley: New York, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sholl D. S.; Lively R. P. Seven Chemical Separations to Change the World. Nature 2016, 532, 435–437. 10.1038/532435a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-R.; Kuppler R. J.; Zhou H.-C. Selective Gas Adsorption and Separation in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1477–1504. 10.1039/b802426j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo P.; Drioli E.; Golemme G. Membrane Gas Separation: A Review/State of the Art. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 4638–4663. 10.1021/ie8019032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders D. F.; Smith Z. P.; Guo R.; Robeson L. M.; McGrath J. E.; Paul D. R.; Freeman B. D. Energy-efficient Polymeric Gas Separation Membranes for a Sustainable Future: A Review. Polymer 2013, 54, 4729–4761. 10.1016/j.polymer.2013.05.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H.; Cordova K. E.; O’Keeffe M.; Yaghi O. M. The Chemistry and Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science 2013, 341, 1230444 10.1126/science.1230444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.-C.; Long J. R.; Yaghi O. M. Introduction to Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 673–674. 10.1021/cr300014x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.-C.; Kitagawa S. Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5415–5418. 10.1039/C4CS90059F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro D. M.; Smit B.; Long J. R. Carbon Dioxide Capture: Prospects for New Materials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6058–6082. 10.1002/anie.201000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.; Drese J. H.; Jones C. W. Adsorbent Materials for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Large Anthropogenic Point Sources. ChemSusChem 2009, 2, 796–854. 10.1002/cssc.200900036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmabkhout Y.; Guillerm V.; Eddaoudi M. Low Concentration CO2 Capture Using Physical Adsorbents: Are Metal–Organic Frameworks Becoming the New Benchmark Materials?. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 296, 386–397. 10.1016/j.cej.2016.03.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herm Z. R.; Bloch E. D.; Long J. R. Hydrocarbon Separations in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 323–338. 10.1021/cm402897c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-R.; Ma Y.; McCarthy M. C.; Sculley J.; Yu J.; Jeong H.-K.; Balbuena P. B.; Zhou H.-C. Carbon Dioxide Capture-Related Gas Adsorption and Separation in Metal-Organic Frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 1791–1823. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett C. A.; Helal A.; Al-Maythalony B. A.; Yamani Z. H.; Cordova K. E.; Yaghi O. M. The Chemistry of Metal–Organic Frameworks for CO2 Capture, Regeneration and Conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 17045. 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-R.; Yu J.; Lu W.; Sun L.-B.; Sculley J.; Balbuena P. B.; Zhou H.-C. Porous Materials with Pre-designed Single-molecule Traps for CO2 Selective Adsorption. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1538 10.1038/ncomms2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X.; Wang Y.; Li D.-S.; Bu X.; Feng P. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Separation. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705189 10.1002/adma.201705189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.; Xie L.-H.; Wang X.; Liu X.-M.; Li J.; Li J.-R. Applications of Metal–organic Frameworks for Green Energy and Environment: New Advances in Adsorptive Gas Separation, Storage and Removal. Green Energy Environ. 2018, 3, 191–228. 10.1016/j.gee.2018.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Zhang B.; Fujiwara H.; Kobayashi H.; Kurmoo M. Mn3(HCOO)6: A 3D Porous Magnet of Diamond Framework with Nodes of Mn-Centered MnMn4 Tetrahedron and Guest-modulated Ordering Temperature. Chem. Commun. 2004, 416–417. 10.1039/B314221C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Zhang B.; Kurmoo M.; Green M. A.; Fujiwara H.; Otsuka T.; Kobayashi H. Synthesis and Characterization of a Porous Magnetic Diamond Framework, Co3(HCOO)6, and Its N2 Sorption Characteristic. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 1230–1237. 10.1021/ic048986r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Zhang B.; Zhang Y.; Kurmoo M.; Liu T.; Gao S.; Kobayashi H. A Family of Porous Magnets, [M3(HCOO)6] (M = Mn, Fe, Co and Ni). Polyhedron 2007, 26, 2207–2215. 10.1016/j.poly.2006.10.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Zhang Y.; Kurmoo M.; Liu T.; Vilminot S.; Zhao B.; Gao S. [Zn3(HCOO)6]: A Porous Diamond Framework Conformable to Guest Inclusion. Aust. J. Chem. 2006, 59, 617–628. 10.1071/CH06176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dybtsev D. N.; Chun H.; Yoon S. H.; Kim D.; Kim K. Microporous Manganese Formate: A Simple Metal–Organic Porous Material with High Framework Stability and Highly Selective Gas Sorption Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 32–33. 10.1021/ja038678c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X.; Sun T.; Hu J.; Wang S. Highly Enhanced Selectivity for the Separation of CH4 Over N2 on Two Ultra-microporous Frameworks with Multiple Coordination Modes. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 186, 137–145. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2013.11.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rood J. A.; Noll B. C.; Henderson K. W. Synthesis, Structural Characterization, Gas Sorption and Guest-Exchange Studies of the Lightweight, Porous Metal–Organic Framework α-[Mg3(O2CH)6]. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 5521–5528. 10.1021/ic060543v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K.; Olson D. H.; Lee J. Y.; Bi W.; Wu K.; Yuen T.; Xu Q.; Li J. Multifunctional Microporous MOFs Exhibiting Gas/Hydrocarbon Adsorption Selectivity, Separation Capability and Three-Dimensional Magnetic Ordering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 2205–2214. 10.1002/adfm.200800058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mallick A.; Saha S.; Pachfule P.; Roy S.; Banerjee R. Structure and Gas Sorption Behavior of a New Three Dimensional Porous Magnesium Formate. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 1392–1401. 10.1021/ic102057p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanopoulos I.; Bratsos I.; Tampaxis C.; Kourtellaris A.; Tasiopoulos A.; Charalambopoulou G.; Steriotis T. A.; Trikalitis P. N. Enhanced Gas-sorption Properties of a High Surface Area, Ultramicroporous Magnesium Formate. CrystEngComm 2015, 17, 532–539. 10.1039/C4CE01667J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viertelhaus M.; Anson C. E.; Powell A. K. Solvothermal Synthesis and Crystal Structure of One-Dimensional Chains of Anhydrous Zinc and Magnesium Formate. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2005, 631, 2365–2370. 10.1002/zaac.200500202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.-P.; Yang H.; Wang F.; Du Z.-Y. A Microporous Manganese-based Metal–Organic Framework for Gas Sorption and Separation. J. Mol. Struct. 2014, 1074, 19–21. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2014.05.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viertelhaus M.; Adler P.; Clérac R.; Anson C. E.; Powell A. K. Iron(II) Formate [Fe(O2CH)2]·1/3HCO2H: A Mesoporous Magnet – Solvothermal Syntheses and Crystal Structures of the Isomorphous Framework Metal(II) Formates [M(O2CH)2]·n(Solvent) (M = Fe, Co, Ni, Zn, Mg). Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 2005, 692–703. 10.1002/ejic.200400395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Zhang Y.; Liu T.; Kurmoo M.; Gao S. [Fe3(HCOO)6]: A Permanent Porous Diamond Framework Displaying H2/N2 Adsorption, Guest Inclusion, and Guest-Dependent Magnetism. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 1523–1536. 10.1002/adfm.200600676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viertelhaus M.; Henke H.; Anson C. E.; Powell A. K. Solvothermal Synthesis and Structure of Anhydrous Manganese(II) Formate, and Its Topotactic Dehydration from Manganese(II) Formate Dihydrate. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 2003, 2283–2289. 10.1002/ejic.200200699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X.; Sun T.; Hu J.; Wang S. Synthesis Optimization of the Ultra-microporous [Ni3(HCOO)6] Framework to Improve Its CH4/N2 Separation Selectivity. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 42326–42336. 10.1039/C4RA05407E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J.; Sun T.; Ren X.; Wang S. HF-assisted Synthesis of Ultra-microporous [Mg3(OOCH)6] Frameworks for Selective Adsorption of CH4 Over N2. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2015, 204, 73–80. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2014.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Hu K.; Gao S.; Kobayashi H. Formate-based Magnetic Metal–Organic Frameworks Templated by Protonated Amines. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 1526–1533. 10.1002/adma.200904438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-W.; Guo Y.; Tao A.; Fischer M.; Sun T.-J.; Moghadam P. Z.; Fairen-Jimenez D.; Wang S.-D. “Explosive” Synthesis of Metal-Formate Frameworks for Methane Capture: An Experimental and Computational Study. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 11437–11440. 10.1039/C7CC06249D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-W.; Sun T.-J.; Guo Y.; Ke Q.-L.; Wang S.-D. Facile and Mild Synthesis of Metal–Formate Frameworks for Methane Adsorptive Separation. Chem. Lett. 2017, 46, 1766–1768. 10.1246/cl.170793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rood J. A.; Henderson K. W. Synthesis and Small Molecule Exchange Studies of a Magnesium Bisformate Metal–Organic Framework: An Experiment in Host–Guest Chemistry for the Undergraduate Laboratory. J. Chem. Educ. 2013, 90, 379–382. 10.1021/ed3000099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.; Lucier B. E. G.; Zhang Y.; Ren P.; Zheng A.; Huang Y. Sizable Dynamics in Small Pores: CO2 Location and Motion in the α-Mg Formate Metal-Organic Framework. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 6130–6141. 10.1039/C7CP00199A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucier B. E. G.; Zhang Y.; Huang Y. Complete Multinuclear Solid-State NMR of Metal-Organic Frameworks: The Case of α-Mg-Formate. Concepts Magn. Reson., Part A 2016, 45A, e21410 10.1002/cmr.a.21410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucier B. E. G.; Zhang Y.; Lee K. J.; Lu Y.; Huang Y. Grasping Hydrogen Adsorption and Dynamics in Metal–Organic Frameworks Using 2H Solid-state NMR. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 7541–7544. 10.1039/C6CC03205B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsonenko D. G.; Kim H.; Sun Y.; Kim G.-H.; Lee H.-S.; Kim K. Microporous Magnesium and Manganese Formates for Acetylene Storage and Separation. Chem. Asian J. 2007, 2, 484–488. 10.1002/asia.200600390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Lucier B. E. G.; Michael F.; Gan Z.; Boyle P. D.; Desveaux B.; Huang Y. A Multifaceted Study of Methane Adsorption in Metal-Organic Frameworks by Using Three Complementary Techniques. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 7866–7881. 10.1002/chem.201800424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham T.; Forrest K. A.; Falcão E. H. L.; Eckert J.; Space B. Exceptional H2 Sorption Characteristics in a Mg2+-based Metal–Organic Framework with Small Pores: Insights From Experimental and Theoretical Studies. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 1786–1796. 10.1039/C5CP05906B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumida K.; Rogow D. L.; Mason J. A.; McDonald T. M.; Bloch E. D.; Herm Z. R.; Bae T.-H.; Long J. R. Carbon Dioxide Capture in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 724–781. 10.1021/cr2003272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M. DFT-based Evaluation of Porous Metal Formates for the Storage and Separation of Small Molecules. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 219, 249–257. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.06.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M.; Hoffmann F.; Fröba M. New Microporous Materials for Acetylene Storage and C2H2/CO2 Separation: Insights from Molecular Simulations. ChemPhysChem 2010, 11, 2220–2229. 10.1002/cphc.201000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth A. J.; Peters A. W.; Vermeulen N. A.; Wang T. C.; Hupp J. T.; Farha O. K. Best Practices for the Synthesis, Activation, and Characterization of Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 26–39. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b02626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gándara F.; Bennett T. D. Crystallography of Metal–Organic Frameworks. IUCrJ 2014, 1, 563–570. 10.1107/S2052252514020351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington E. J.; Vitórica-Yrezábal I. J.; Brammer L. Crystallographic Studies of Gas Sorption in Metal-Organic Frameworks. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2014, 70, 404–422. 10.1107/S2052520614009834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.-P.; Liao P.-Q.; Zhou H.-L.; Lin R.-B.; Chen X.-M. Single-crystal X-ray Diffraction Studies on Structural Transformations of Porous Coordination Polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5789–5814. 10.1039/C4CS00129J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowsell J. L. C.; Spencer E. C.; Eckert J.; Howard J. A. K.; Yaghi O. M. Gas Adsorption Sites in a Large-Pore Metal-Organic Framework. Science 2005, 309, 1350–1354. 10.1126/science.1113247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. R.; Wright P. A.; Devic T.; Serre C.; Férey G.; Llewellyn P. L.; Denoyel R.; Gaberova L.; Filinchuk Y. Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction Studies of Carbon Dioxide and Fuel-Related Gases Adsorbed on the Small Pore Scandium Terephthalate Metal Organic Framework, Sc2(O2CC6H4CO2)3. Langmuir 2009, 25, 3618–3626. 10.1021/la803788u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao P.-Q.; Zhou D.-D.; Zhu A.-X.; Jiang L.; Lin R.-B.; Zhang J.-P.; Chen X.-M. Strong and Dynamic CO2 Sorption in a Flexible Porous Framework Possessing Guest Chelating Claws. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 17380–17383. 10.1021/ja3073512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidhyanathan R.; Iremonger S. S.; Shimizu G. K. H.; Boyd P. G.; Alavi S.; Woo T. K. Direct Observation and Quantification of CO2 Binding Within an Amine-Functionalized Nanoporous Solid. Science 2010, 330, 650–653. 10.1126/science.1194237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.; Wang X.; Omary M. A. Crystallographic Observation of Dynamic Gas Adsorption Sites and Thermal Expansion in a Breathable Fluorous Metal–Organic Framework. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2500–2505. 10.1002/anie.200804739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. B.; Furukawa H.; Nam H. J.; Jung D.-Y.; Jhon Y. H.; Walton A.; Book D.; O’Keeffe M.; Yaghi O. M.; Kim J. Reversible Interpenetration in a Metal–Organic Framework Triggered by Ligand Removal and Addition. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 8791–8795. 10.1002/anie.201202925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock N.; Wu Y.; Christensen M.; Cameron L. J.; Peterson V. K.; Bridgeman A. J.; Kepert C. J.; Iversen B. B. Elucidating Negative Thermal Expansion in MOF-5. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 16181–16186. 10.1021/jp103212z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Li S.; Zheng A.; Liu X.; Yu N.; Deng F. Solid-state NMR Studies of Host–Guest Interaction between UiO-67 and Light Alkane at Room Temperature. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 14261–14268. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b04611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gul-E-Noor F.; Michel D.; Krautscheid H.; Haase J.; Bertmer M. Time Dependent Water Uptake in Cu3(btc)2 MOF: Identification of Different Water Adsorption States by 1H MAS NMR. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 180, 8–13. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2013.06.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Li J.; Tang J.; Deng F. Host-guest Interaction of Styrene and Ethylbenzene in MIL-53 Studied by Solid-state NMR. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 2018, 90, 1–6. 10.1016/j.ssnmr.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda T.; Kurokawa K.; Omichi H.; Miyakubo K.; Eguchi T. Phase Transition and Molecular Motion of Cyclohexane Confined in Metal-Organic Framework, IRMOF-1, as Studied by 2H NMR. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007, 443, 293–297. 10.1016/j.cplett.2007.06.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X.; Scott E.; Ding W.; Mason J. A.; Long J. R.; Reimer J. A. CO2 Dynamics in a Metal–Organic Framework with Open Metal Sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 14341–14344. 10.1021/ja306822p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.-C.; Kim J.; Kong X.; Scott E.; McDonald T. M.; Long J. R.; Reimer J. A.; Smit B. Understanding CO2 Dynamics in Metal–Organic Frameworks with Open Metal Sites. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4410–4413. 10.1002/anie.201300446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. D.; Lucier B. E. G.; Terskikh V. V.; Wang W.; Huang Y. Wobbling and Hopping: Studying Dynamics of CO2 Adsorbed in Metal–Organic Frameworks via 17O Solid-State NMR. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 3360–3365. 10.1021/jz501729d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Lucier B. E. G.; Huang Y. Deducing CO2 motion, Adsorption Locations and Binding Strengths in a Flexible Metal-Organic Framework without Open Metal Sites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 8327–8341. 10.1039/C5CP04984A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Lucier B. E. G.; McKenzie S. M.; Arhangelskis M.; Morris A. J.; Friščić T.; Reid J. W.; Terskikh V. V.; Chen M.; Huang Y. Welcoming Gallium- and Indium-Fumarate MOFs to the Family: Synthesis, Comprehensive Characterization, Observation of Porous Hydrophobicity, and CO2 Dynamics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 28582–28596. 10.1021/acsami.8b08562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gul-E-Noor F.; Mendt M.; Michel D.; Pöppl A.; Krautscheid H.; Haase J.; Bertmer M. Adsorption of Small Molecules on Cu3(btc)2 and Cu3–xZnx(btc)2 Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOF) As Studied by Solid-State NMR. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 7703–7712. 10.1021/jp400869f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marti R. M.; Howe J. D.; Morelock C. R.; Conradi M. S.; Walton K. S.; Sholl D. S.; Hayes S. E. CO2 Dynamics in Pure and Mixed-Metal MOFs with Open Metal Sites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 25778–25787. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b07179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.; Lucier B. E. G.; Boyle P. D.; Huang Y. Understanding The Fascinating Origins of CO2 Adsorption and Dynamics in MOFs. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 5829–5846. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b02239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brozek C. K.; Michaelis V. K.; Ong T.-C.; Bellarosa L.; López N.; Griffin R. G.; Dincă M. Dynamic DMF Binding in MOF-5 Enables the Formation of Metastable Cobalt-Substituted MOF-5 Analogues. ACS Cent. Sci. 2015, 1, 252–260. 10.1021/acscentsci.5b00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutrisno A.; Terskikh V. V.; Shi Q.; Song Z.; Dong J.; Ding S. Y.; Wang W.; Provost B. R.; Daff T. D.; Woo T. K.; Huang Y. Characterization of Zn-Containing Metal–Organic Frameworks by Solid-State 67Zn NMR Spectroscopy and Computational Modeling. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 12251–12259. 10.1002/chem.201201563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vold R. L.; Hoatson G. L. Effects of Jump Dynamics on Solid State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Line Shapes and Spin Relaxation Times. J. Magn. Reson. 2009, 198, 57–72. 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeler A. J.; Orendt A. M.; Grant D. M.; Cutts P. W.; Michl J.; Zilm K. W.; Downing J. W.; Facelli J. C.; Schindler M. S.; Kutzelnigg W. Low-Temperature 13C Magnetic Resonance in Solids. 3. Linear and Pseudolinear Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 7672–7676. 10.1021/ja00337a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.; Chen S.; Chen W.; Lucier B. E. G.; Zhang Y.; Zheng A.; Huang Y. Analyzing Gas Adsorption in an Amide-Functionalized Metal Organic Framework: Are the Carbonyl or Amine Groups Responsible?. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 3613–3617. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b00681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H.; Wei W.; Li Y.; Wu R.; Feng G.; Li W. Uniaxial Negative Thermal Expansion and Mechanical Properties of a Zinc-Formate Framework. Materials 2017, 10, 151. 10.3390/ma10020151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collings I. E.; Hill J. A.; Cairns A. B.; Cooper R. I.; Thompson A. L.; Parker J. E.; Tang C. C.; Goodwin A. L. Compositional Dependence of Anomalous Thermal Expansion in Perovskite-like ABX3 Formates. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 4169–4178. 10.1039/C5DT03263F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witherspoon V. J.; Xu J.; Reimer J. A. Solid-State NMR Investigations of Carbon Dioxide Gas in Metal–Organic Frameworks: Insights into Molecular Motion and Adsorptive Behavior. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 10033–10048. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines A.; Gibby M. G.; Waugh J. S. Proton-enhanced NMR of Dilute Spins in Solids. J. Chem. Phys. 1973, 59, 569–590. 10.1063/1.1680061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breck D. W.Zeolite Molecular Sieves: Structure, Chemistry and Use; Wiley: New York, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Thirumurugan A.; Barton P. T.; Lin Z.; Henke S.; Yeung H. H.-M.; Wharmby M. T.; Bithell E. G.; Howard C. J.; Cheetham A. K. Mechanical Tunability via Hydrogen Bonding in Metal–Organic Frameworks with the Perovskite Architecture. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7801–7804. 10.1021/ja500618z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y. T. A.; Babcock T. K.; Chen S.; Lucier B. E. G.; Huang Y. CO Guest Interactions in SDB-based Metal-Organic Frameworks – A Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Investigation. Langmuir 2018, 34, 15640–15649. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b02205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordiga S.; Regli L.; Bonino F.; Groppo E.; Lamberti C.; Xiao B.; Wheatley P. S.; Morris R. E.; Zecchina A. Adsorption Properties of HKUST-1 Toward Hydrogen and Other Small Molecules Monitored by IR. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 2676–2685. 10.1039/b703643d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García E. J.; Mowat J. P. S.; Wright P. A.; Pérez-Pellitero J.; Jallut C.; Pirngruber G. D. Role of Structure and Chemistry in Controlling Separations of CO2/CH4 and CO2/CH4/CO Mixtures over Honeycomb MOFs with Coordinatively Unsaturated Metal Sites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 26636–26648. 10.1021/jp309526k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzano L.; Civalleri B.; Chavan S.; Palomino G. T.; Areán C. O.; Bordiga S. Computational and Experimental Studies on the Adsorption of CO, N2, and CO2 on Mg-MOF-74. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 11185–11191. 10.1021/jp102574f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzano L.; Civalleri B.; Sillar K.; Sauer J. Heats of Adsorption of CO and CO2 in Metal–Organic Frameworks: Quantum Mechanical Study of CPO-27-M (M = Mg, Ni, Zn). J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 21777–21784. 10.1021/jp205869k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Li H.; Hou X.-J. Amine-Functionalized Metal Organic Framework as a Highly Selective Adsorbent for CO2 over CO. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 19814–19821. 10.1021/jp3052938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Doan V. D.; Cho W. J.; Valero R.; Tehrani A. Z.; Madridejos J. M. L.; Kim K. S. Intriguing Electrostatic Potential of CO: Negative Bond-ends and Positive Bond-cylindrical-surface. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16307 10.1038/srep16307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A. Y. Theoretical Investigation of Hydrogen Bonds between CO and HNF2, H2NF, and HNO. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 10805–10816. 10.1021/jp062291p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areán C. O. Dinitrogen and Carbon Monoxide Hydrogen Bonding in Protonic Zeolites: Studies From Variable-temperature Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 2008, 880, 31–37. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2007.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Areán C. O.; Tsyganenko A. A.; Manoilova O. V.; Palomino G. T.; Mentruit M. P.; Garrone E. Amphipathic Hydrogen Bonding of CO in Protonic Zeolites. Chem. Commun. 2001, 455–456. 10.1039/b009747k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruker-AXS . SAINT, version 2013.8; Bruker-AXS: Madison, WI, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bruker-AXS . SADABS, version 2012.1; Bruker-AXS: Madison, WI, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dybowski C.; Neue G. Solid state 207Pb NMR spectroscopy. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2002, 41, 153–170. 10.1016/S0079-6565(02)00005-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cory D. G.; Ritchey W. M. Suppression of Signals From the Probe in Bloch Decay Spectra. J. Magn. Reson. (1969) 1988, 80, 128–132. 10.1016/0022-2364(88)90064-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eichele K.WSolids, version 1.20.21; University of Tübingen: Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.