Abstract

Herein, we report a novel type of smart graphene oxide nanocomposites (MGO@PNB) with excellent magnetism and high thermosensitive ion-recognition selectivity of lead ions (Pb2+). The MGO@PNB are fabricated by immobilizing superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles (NPs) and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-benzo-18-crown-6 acrylamide) thermosensitive microgels (PNB) onto graphene oxide (GO) nanosheets using a simple one-step solvothermal method and mussel-inspired polydopamine chemistry. The PNB are composed of cross-linked poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) chains with numerous appended 18-crown-6 units. The 18-crown-6 units serve as hosts that can selectively recognize and capture Pb2+ from aqueous solution, and the PNIPAM chains act as a microenvironmental actuator for the inclusion constants of 18-crown-6/Pb2+ host–guest complexes. The loaded Fe3O4 NPs endow the MGO@PNB with convenient magnetic separability. The fabricated MGO@PNB demonstrate remarkably high ion-recognition selectivity of Pb2+ among the coexisting metal ions because of the formation of stable 18-crown-6/Pb2+ inclusion complexes. Most interestingly, the MGO@PNB show excellent thermosensitive adsorption ability toward Pb2+ due to the incorporation of PNIPAM functional chains on the GO. Further thermodynamic studies indicate that the adsorption of Pb2+ onto the MGO@PNB is a spontaneous and endothermic process. The adsorption kinetics and isotherm data can be well described by the pseudo-second-order kinetic model and the Langmuir isotherm model, respectively. Most importantly, the Pb2+-loaded MGO@PNB can be more easily regenerated by alternatively washing with hot/cold water than the commonly used regeneration methods. Such multifunctional graphene oxide nanocomposites could be used for specific recognition and removal of Pb2+ from water environment.

1. Introduction

Lead is one of the most common heavy metals, which is widely used in modern industries, including storage batteries, painting pigments, ammunitions, textiles and steels, etc.1−3 Lead ions (Pb2+) are usually delivered in soil and water body along with industrial wastewater and can accumulate in the human body through food chains or drinking water, thus causing serious effects on human health and environment.4−7 Even a very low level of lead intake can bring about permanent damage to the central nerve system, immune system, brain, and kidneys,1−7 especially to children’s intellectual development.8−10 Therefore, effective recognition and removal of Pb2+ from aqueous environment is of vital importance, and there is a great scientific significance for water treatment.1 To date, a variety of technologies have been developed to identify and remove Pb2+ from water environment, such as precipitation, ion exchange, solvent extraction, membrane process, and adsorption.3,11−18 By contrast, adsorption is a competitive approach because of its easy operation, high efficiency, and low cost.3,12−14,19−22 The key of this technology is to develop high-performance adsorbents. Traditional adsorbents for Pb2+ recognition and removal have some drawbacks, such as lack of selectivity and sensitivity, tedious operational process, and low efficiency, which have restricted their wide applications. Therefore, to develop high-performance adsorbent materials for specific recognition and removal of Pb2+ from water environment is highly desired.

Various kinds of functional materials, including hydrogel-based devices, gating membranes, and porous nanomaterials, have been recently developed for specific recognition and removal of Pb2+ from water.11,23−28 Among those materials, 18-crown-6, possessing remarkably high selectivity and sensitivity toward Pb2+ by forming stable 1:1 (18-crown-6/Pb2+) inclusion complexes, provides a novel strategy to specifically discriminate and remove Pb2+ from aqueous solution.11,26−30 For example, novel Pb2+-imprinted crown ether (Pb(II)-IIP) particles were synthesized by using Pb2+ as template and 4-vinylbenzo-18-crown-6 as a functional monomer to specifically recognize and remove Pb2+ from environmental water.26 Several Pb2+-responsive smart materials were also developed to detect and remove Pb2+ from aqueous solution by incorporating 18-crown-6 units into poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) polymers.11,27,28,31 PNIPAM, a well-known thermosensitive polymer, can experience dramatic swelling/shrinking conformational changes as environmental temperature is changed across its lower critical solution temperature (LCST) around 32 °C. More importantly, those Pb2+-responsive smart materials can be facilely regenerated by raising the ambient temperature above the LCST of PNIPAM chains, which results in the desorption of Pb2+ from the cavity of crown ether. Although those crown ether-based smart materials can selectively identify and remove Pb2+ from aqueous solution, most of these processes are sophisticated and have low efficiency. Magnetic graphene oxide (MGO) typically obtained by depositing some superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles (NPs) onto the graphene oxide (GO)32−34 is an excellent adsorption material due to its large specific surface area, high stability, abundant oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface, and convenient magnetic separability.35−43 But it cannot be utilized in specific recognition and removal of Pb2+ from aqueous environment because of the lack of ion-recognized sites on the surface, which limits its practical applications to some extent. Incorporating some smart materials, such as 18-crown-6 with high ion-recognition selectivity44 and PNIPAM with excellent thermosensitivity, into MGO to fabricate smart nanocomposites could address the above-mentioned problems.

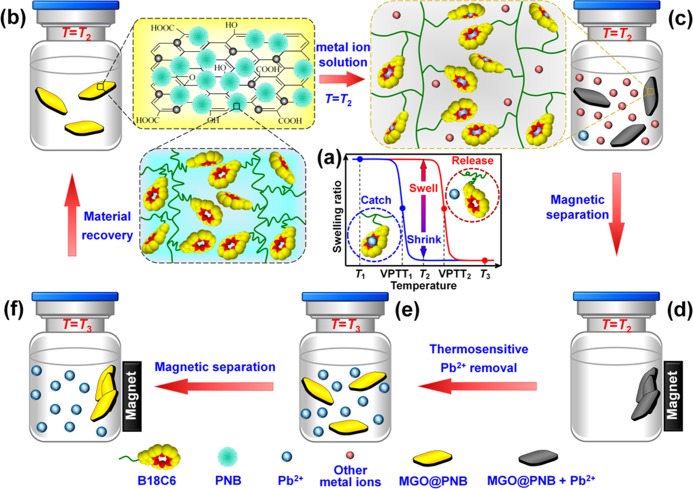

Herein, we report a novel type of smart graphene oxide nanocomposites (MGO@PNB) with excellent magnetism and highly thermoresponsive ion-recognition selectivity of Pb2+ based on the host–guest interactions of 18-crown-6 and Pb2+. The MGO@PNB are fabricated by immobilizing superparamagnetic Fe3O4 NPs and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-benzo-18-crown-6 acrylamide) thermosensitive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-benzo-18-crown-6 acrylamide) (PNB) microgels onto the graphene oxide (GO) nanosheets using the simple one-step solvothermal method and mussel-inspired polydopamine chemistry. The PNB are composed of cross-linked PNIPAM chains with numerous appended 18-crown-6 units, which serve as host receptors to specifically recognize and capture Pb2+ from aqueous solution. The PNIPAM chains act as a microenvironmental actuator for the inclusion constants of 18-crown-6/Pb2+ complexes. The proposed concept of the thermosensitive adsorption and separation of Pb2+ from aqueous solution by MGO@PNB is schematically illustrated in Figure 1. When Pb2+ ions appear in aqueous solution, the pendent 18-crown-6 units can capture them by forming stable charged 18-crown-6/Pb2+ complexes. This will cause the volume phase-transition temperature (VPTT) of PNB to shift positively from a low-temperature VPTT1 to a higher-temperature VPTT2 because of the enhancement of hydrophilicity of the polymer chains and the repulsion among the charged 18-crown-6/Pb2+ complexes (Figure 1a).11,28,44 As the operating temperature (T2) is set between VPTT1 and VPTT2, the PNB isothermally change from a shrunken state to a swollen one by recognizing Pb2+ in aqueous solution. As a result, Pb2+ are easily captured by 18-crown-6 units and removed from the water as the ambient temperature is kept at a certain value below VPTT2 (Figure 1b,c). After the complexes of 18-crown-6 and the captured Pb2+ reach saturation on the MGO@PNB, the Pb2+-recognized MGO@PNB can be easily isolated from water under an external magnet (Figure 1c,d). Afterward, the PNB become shrunken and hydrophobic as the operating temperature is increased to T3 above the VPTT2. This causes the desorption of Pb2+ from the 18-crown-6 units because of the thermo-induced reduction in inclusion constants between 18-crown-6 and the captured Pb2+ (Figure 1e).11,45,46 That is to say, the recognition and separation of Pb2+ from the aqueous solution and the regeneration of MGO@PNB can be easily achieved by simply varying the operating temperature and applying an external magnetic field (Figure 1f).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the thermosensitive adsorption and separation of Pb2+ from aqueous solution by MGO@PNB. (a) Pendent 18-crown-6 units on the PNB microgels can capture Pb2+ ions by forming stable charged 18-crown-6/Pb2+ complexes, which cause the volume phase-transition temperature (VPTT) of PNB to shift positively from a low-temperature VPTT1 to a higher-temperature VPTT2 because of the enhancement of hydrophilicity of the polymer chains and the repulsion among the charged 18-crown-6/Pb2+ complexes. (b, c) As the operating temperature (T2) is set between VPTT1 and VPTT2, the PNB isothermally change from a shrunken state to a swollen one by recognizing Pb2+ in aqueous solution. As a result, Pb2+ are easily captured by 18-crown-6 units and removed from the water as the ambient temperature is kept at a certain value below VPTT2. (d) After the complexes of 18-crown-6 and the captured Pb2+ reach saturation on the MGO@PNB, the Pb2+-recognized MGO@PNB can be easily isolated from water under an external magnet. (e) PNB become shrunken and hydrophobic as the operating temperature is increased to T3 above the VPTT2. This causes the desorption of Pb2+ from the 18-crown-6 units because of the thermo-induced reduction in inclusion constants between 18-crown-6 and the captured Pb2+. (f) Separation of Pb2+ from the aqueous solution and the regeneration of MGO@PNB can be achieved by simply varying the operating temperature and applying an external magnetic field.

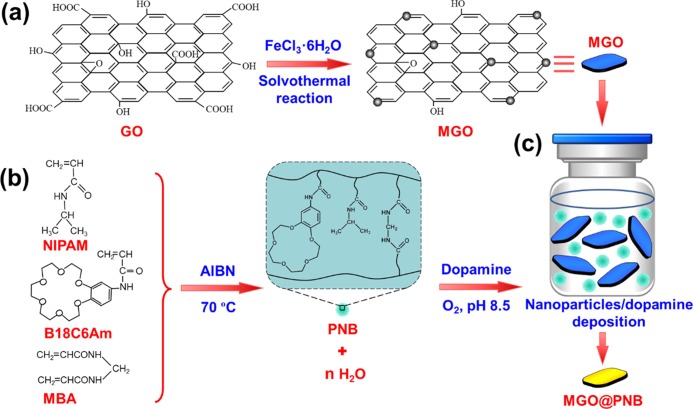

The detailed fabrication process of MGO@PNB is shown in Figure 2. First, MGO are prepared by a versatile one-step solvothermal method (Figure 2a).47−50 Then, PNB are synthesized by a simple precipitation copolymerization method using N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) and acrylamide-modified benzo-18-crown-6 (B18C6Am) as the functional monomers (Figure 2b).51 The PNB are immobilized onto the MGO via self-polymerization of bio-adhesive dopamine (DA) at a weak alkaline condition (pH 8.5, Figure 2c), finally causing the formation of MGO@PNB.52−56 Since DA is a biomolecule with plentiful catechol and amine functional groups and can easily self-polymerize into polydopamine (PDA) under weak alkaline conditions, these multifunctional PDA layers endow strong adhesion onto a wide range of substrates. The unique property of PDA provides an effective strategy to immobilize PNB onto the MGO.52−56 Compared to the current technologies, the suggested separation process by using such smart graphene nanocomposites is facilely operated and environmentally friendly, which shows great potentials in specific recognition and removal of Pb2+ from water environment.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the fabrication of MGO@PNB. (a) MGO are prepared by a one-step solvothermal method. (b) PNB are synthesized by a simple precipitation copolymerization method by using N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) and acrylamide-modified benzo-18-crown-6 (B18C6Am) as the functional monomers. (c) PNB are immobilized onto the MGO via self-polymerization of bio-adhesive dopamine (DA) at a weak alkaline condition (pH 8.5).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Materials Characterizations

The typical TEM images of MGO and MGO@PNB are shown in Figure 3a,b. Compared to the MGO, the MGO@PNB show a dramatically different microstructure. They have a crumpled and flakelike structure, and the GO nanosheets are loaded with black Fe3O4 NPs with an average size of about 80 nm, which endows the MGO@PNB with excellent magnetic separability. After depositing of PNB onto the MGO, grayish PNB microgels with good sphericity and monodispersity are observed on the MGO. The morphological and microstructural changes of nanocomposites indicate the successful immobilization of PNB onto the MGO, thus resulting in the formation of MGO@PNB.

Figure 3.

Typical TEM images of MGO (a) and MGO@PNB (b). (c) Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra of MGO, MGO@PNB, and PNB. (d) TG curves of MGO and MGO@PNB. (e) Magnetization hysteresis loops of MGO and MGO@PNB at room temperature. The insets show the dispersion (a′) and separation (b′) behaviors of MGO@PNB in the absence and presence of an external magnetic field in water.

The successful fabrication of MGO@PNB is also confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy. Figure 3c shows the FT-IR spectra of MGO, MGO@PNB, and PNB. The characteristic peaks of GO at 1043 cm–1 for the C–O–C stretching vibration in epoxy group and at 1724 cm–1 for the C=O stretching vibration of −COOH groups are all found in the FT-IR spectrum of MGO. Moreover, the characteristic peaks at 592 cm–1 for the Fe–O stretching vibration, the asymmetric stretching vibrations of −SO3– groups at 1213 cm–1, and the C=O asymmetric stretching vibrations of COO– in PSSMA at 1407 and 1581 cm–1 are also observed, indicating a successful anchoring of Fe3O4 NPs and PSSMA molecules onto the GO.47−50 After immobilizing PNB onto the MGO, the typical double peaks at 1363 and 1392 cm–1 for isopropyl group and the characteristic peak of C=O stretching vibrations at 1648 cm–1 from PNIPAM are all found in the FT-IR spectra of MGO@PNB.51 Meanwhile, the peaks of benzo-18-crown-6, including a strong peak at 1521 cm–1 (shoulder peak) for C=C skeletal stretching vibration in the phenyl ring, a peak at 1230 cm–1 for C–O asymmetric stretching vibration in Ar–O–R groups,51 and a peak at 1128 cm–1 for C–O symmetric stretching vibration in R–O–R groups, are also observed in the FT-IR spectra of MGO@PNB, indicating the successful fabrication of MGO@PNB.

The thermal properties of MGO and MGO@PNB are shown in Figure 3d. For MGO, the first weight loss at temperature below about 350 °C is attributed to the evaporation of the physically adsorbed water onto the MGO, and the second mass loss from 350 to 600 °C is due to the decomposition of −COOH, −OH, and C–O–C groups from GO and PSSMA molecules covalently bound onto the MGO.50 Compared to the TG curve of MGO, the MGO@PNB demonstrate a weight loss of 44.80 wt % due to the decomposition of PNB and PDA thin layer onto the MGO. The immobilization amount of PNB onto the MGO is calculated to be about 295.1 mg/g on the basis of the TGA results, which shows again the successful fabrication of MGO@PNB.

The loaded Fe3O4 NPs onto the MGO@PNB enable the functional nanocomposites with convenient magnetic separability from contaminated aqueous solution. The magnetization hysteresis loops of the MGO and MGO@PNB at room temperature are shown in Figure 3e. The hysteresis and coercivity are almost undetectable when the applied magnetic field is removed, indicating high superparamagnetism of the MGO and MGO@PNB. Therefore, these functional nanocomposites will not aggregate by retaining any magnetism, and will be redispersed rapidly after removing the external magnet (Figure 3a′, inset). The magnetization saturation (Ms) values of the MGO and MGO@PNB are 34.9 and 15.9 emu/g, respectively. The obvious decrease of the Ms value is due to the existence of nonmagnetic organic substances, including PNB and PDA layer on the MGO. However, the MGO@PNB still demonstrate excellent magnetic responsiveness and can be completely isolated from the aqueous solution under an external magnetic field within 2 min, and then redispersed in water by slight shaking (Figure 3b′, inset). Such excellent magnetism of the MGO@PNB facilitates good recycling of the functional nanocomposites from water.

2.2. Theremoresponsive Property and Pb2+-Recognized Responsive Behaviors of PNB

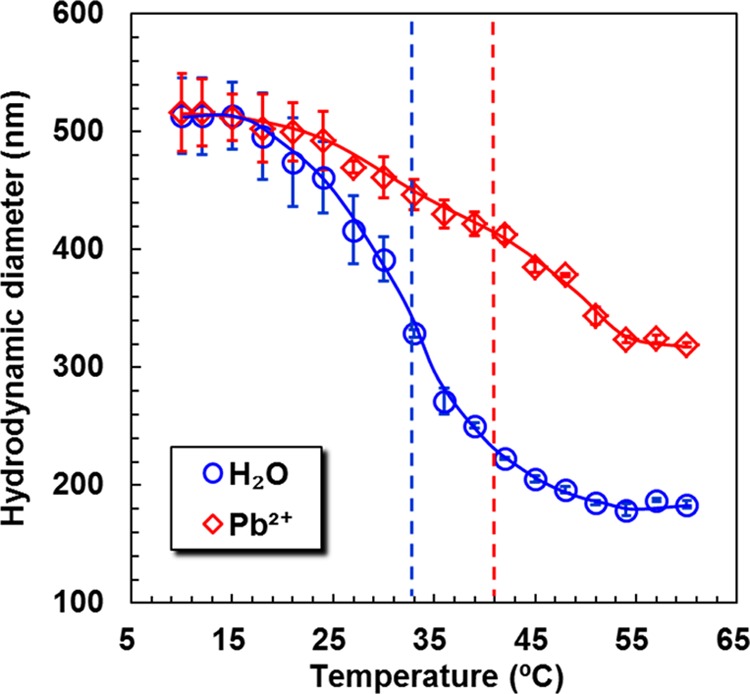

The thermosensitive shrunken behaviors of PNB microgels in water and Pb2+ aqueous solution (20 mmol/L) are shown in Figure 4. As expected, PNB in both water and Pb2+ aqueous solution undergo rapid size decrease as the environmental temperature is varied across a corresponding temperature region due to the excellent thermosensitivity of PNIPAM chains. The volume phase-transition temperature (VPTT) of PNB in water is around 33 °C, consistent with the VPTT of pure PNIPAM microgels (∼32 °C).51 By contrast, the hydrodynamic diameters of PNB decrease dramatically at higher temperatures in Pb2+ aqueous solution upon increasing the temperature. The VPTT of PNB in Pb2+ aqueous solution shifts obviously to a higher temperature (∼41 °C) compared to that in water, showing an evident Pb2+-recognized responsive property. Such a dramatically positive shift of VPTT for PNB in Pb2+ aqueous solution is due to the enhancement of hydrophilicity of the copolymer and the repulsion interactions among the charged 18-crown-6/Pb2+ complexes.11,28,57 That is to say, PNB can isothermally change from a shrunken state to a swollen one in the presence of Pb2+ as the ambient temperature is set at a certain value between the two VPTTs of microgels in water and Pb2+ aqueous solution.

Figure 4.

Temperature-dependent shrunken behaviors of PNB in water and 20 mmol/L Pb2+ aqueous solution.

2.3. Thermosensitive Adsorption and Thermodynamic Study of Pb2+ by MGO@PNB

As observed in Figure 4, the PNB microgels immobilized onto the MGO@PNB exhibit dramatically thermosensitive volume phase changes in Pb2+ aqueous solutions as the environmental operating temperature is varied across its VPTT due to the excellent thermosensitivity of PNIPAM chains. Therefore, verification of the Pb2+ adsorption and the regeneration of functional nanocomposites can be easily achieved by simply changing the operating temperature, and the thermosensitive adsorption of Pb2+ onto the MGO@PNB is investigated at three typical temperatures (25, 45, and 65 °C) and the results are shown in Figure 5a. The equilibrium adsorption of Pb2+ onto the MGO@PNB at 25 °C (lower than the VPTT value of PNB) is much higher than that at 45 °C (slightly higher than the VPTT value of PNB) and 65 °C (higher than the VPTT value of PNB). This indicates that the thermosensitivity of PNIPAM chains onto the MGO@PNB affects the interactions between the 18-crown-6 units and Pb2+. Such dramatic thermo-induced reduction in adsorption capacities of Pb2+ onto the MGO@PNB is mainly due to the decrease of the inclusion constant of 18-crown-6/Pb2+ complexes as the environmental operating temperature is increased.11,45,46,58 As the environmental operating temperature is set at 25 °C, the PNIPAM chains are swollen and the inclusion constants of 18-crown-6/Pb2+ complexes are large, which is beneficial for 18-crown-6 units to capture Pb2+ from aqueous solution and form stable 18-crown-6/Pb2+ inclusion complexes, thus leading to higher adsorption capacities of MGO@PNB toward Pb2+. However, as the environmental operating temperature is increased above the VPTT value of PNB, the PNIPAM chains are shrunken and the inclusion constants of 18-crown-6/Pb2+ complexes decrease. As a result, part of captured Pb2+ release from the cavities of 18-crown-6 units, causing decrease of adsorption capacities of Pb2+. Therefore, the MGO@PNB can be conveniently regenerated by simply raising the environmental temperature.

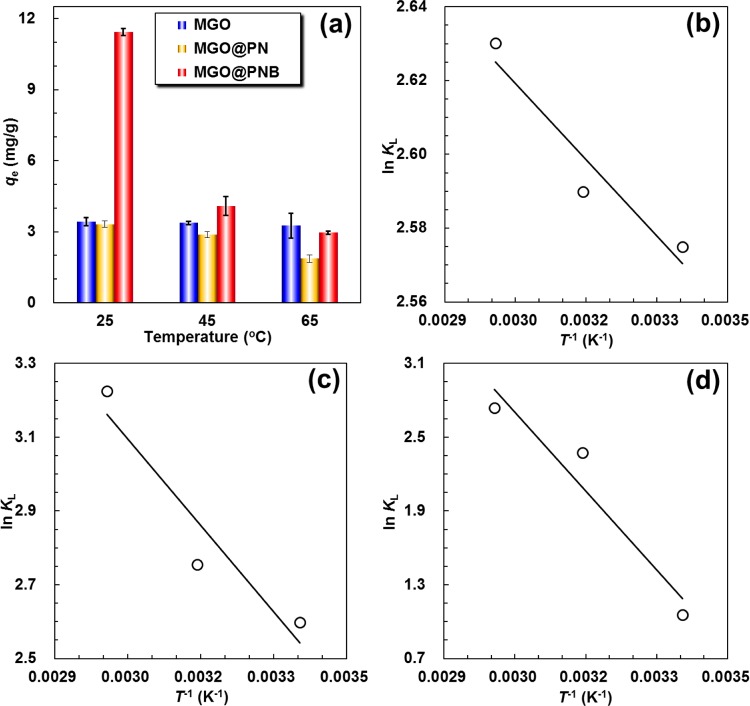

Figure 5.

(a) Thermosensitive adsorption of Pb2+ onto the MGO, MGO@PN, and MGO@PNB at 25, 45, and 65 °C. van’t Hoff plots for adsorption of Pb2+ onto the MGO (b), MGO@PN (c), and MGO@PNB (d). The initial concentration of Pb2+ and the dosage of adsorbents were 50 and 1.5 mg/mL, respectively.

By contrast, the equilibrium adsorption capacities of Pb2+ onto MGO@PN and MGO at 25 °C are much lower than those of MGO@PNB since MGO@PN and MGO cannot form 18-crown-6/Pb2+ inclusion complexes with Pb2+ due to the absence of crown ether units. Moreover, the equilibrium adsorption capacity of Pb2+ onto the MGO at 25 °C is almost the same as that at 45 and 65 °C, showing no thermosensitive adsorption ability of MGO toward Pb2+, while the equilibrium adsorption capacity of Pb2+ onto the MGO@PN at 25 °C is slightly higher than those at 45 and 65 °C because of the presence of thermosensitive PNIPAM chains onto the MGO@PN.

To further investigate the adsorption mechanisms of Pb2+ onto the functional nanocomposites, the thermodynamic parameters for the adsorption process, such as free-energy change (ΔG), enthalpy change (ΔH), and entropy change (ΔS), which provide in-depth information about internal energy changes that are associated with adsorption, were calculated by the following van’t Hoff equations:59−61

| 1 |

| 2 |

where KL is the Langmuir constant, R is the gas constant (8.314 J/(mol K)), and T is the temperature (K). The enthalpy change is obtained by calculating the slope of a plot of ln KL versus T–1 (Figure 5b–d), and the thermodynamic parameters obtained at three different temperatures are listed in Table 1. The negative values of ΔG indicate that the adsorption processes of Pb2+ onto these functional nanocomposites are feasible and spontaneous.59−61 The more negative value of ΔG with the decrease of temperature indicates that lower temperature would be beneficial for the adsorption. The negative values of slope or the positive values of ΔH suggest the endothermic adsorption processes, and the positive values of ΔS reflect the increased randomness at the solid–liquid interface during the adsorption of Pb2+ onto those functional nanocomposites.59−61

Table 1. Thermodynamic Parameters for the Adsorption of Pb2+ onto MGO, MGO@PN, and MGO@PNB at Different Temperatures.

| adsorbent | T (K) | ln KL | ΔG (kJ/mol) | ΔH (kJ/mol) | ΔS (J/(mol K)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGO | 298.15 | 2.57 | –6.37 | 1.14 | 25.21 |

| 318.15 | 2.59 | –6.88 | |||

| 338.15 | 2.63 | –7.38 | |||

| MGO@PN | 298.15 | 2.60 | –6.30 | 12.96 | 64.61 |

| 318.15 | 2.75 | –7.60 | |||

| 338.15 | 3.22 | –8.89 | |||

| MGO@PNB | 298.15 | 1.06 | –2.94 | 35.64 | 129.42 |

| 318.15 | 2.38 | –5.53 | |||

| 338.15 | 2.74 | –8.12 |

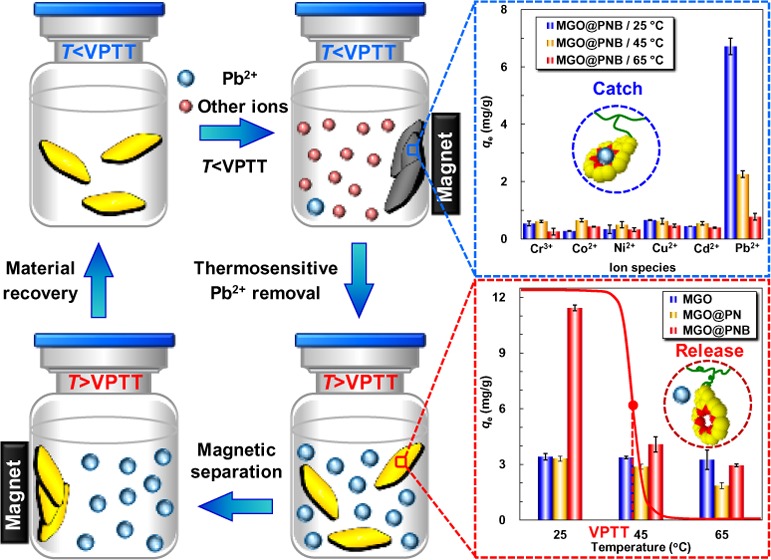

2.4. Thermosensitive Ion-Recognition Selectivity of MGO@PNB

To evaluate the ion-recognition selectivity of MGO@PNB toward specific metal ions, the Pb2+ adsorption experiments at different temperatures in mixed metal ions solutions as a simulate-contaminated wastewater containing some common coexisting ions, such as Pb2+, Cr3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Cd2+, are investigated and the results are shown in Figure 6. The adsorption ability of MGO@PNB toward Pb2+ at 25 °C is much higher than that at 45 and 65 °C. This is due to that a much larger inclusion constant of 18-crown-6/Pb2+ complexes benefited from the swollen PNIPAM chains while the operating temperature (25 °C) is lower than the VPTT value of PNB, which is consistent with the results in Figure 5a. Most interestingly, the MGO@PNB with 18-crown-6 units exhibit much higher adsorption ability toward Pb2+, and the equilibrium adsorption capacity of Pb2+ at 25 °C is almost 7 times higher than that of the other metal ions. The significant difference in the adsorption capacities of different metal ions onto the MGO@PNB is mainly due to the selective formation of crown-ether/metal-ion inclusion complexes between 18-crown-6 units and the suitable metal ions, which is dominated by the size/shape fitting or matching effects between the host (crown ether receptor) and the guest (metal ions).44,46,57,62 MGO@PNB are capable of specifically and selectively capturing Pb2+ from the mixed metal-ion solutions to form stable 18-crown-6/Pb2+ inclusion complexes. This remarkably increases the adsorption capacity of MGO@PNB toward Pb2+.11,28,44,57 By contrast, the metal ions, such as Cr3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Cd2+, cannot form inclusion complexes with 18-crown-6 units because of unfit or unmatched size/shape,44,57 thus resulting in small adsorption capacities of Cr3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Cd2+ onto the MGO@PNB. Therefore, these metal ions cannot be effectively recognized and removed by MGO@PNB. As a comparison, MGO and MGO@PN without 18-crown-6 units demonstrate low adsorption abilities toward all of the metal ions at all setting temperatures. The adsorption capacities are much lower than that of MGO@PNB because of no crown ether units on the MGO to form complexes with metal ions. The metal ions in solutions can only interact with −COO– groups on the MGO via electrostatic attractions, thus exhibiting very low adsorption ability toward metal ions.63

Figure 6.

Specific recognition and adsorption of Pb2+ onto MGO (a), MGO@PN (b), and MGO@PNB (c) in mixed metal-ion solutions containing Pb2+, Cr3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Cd2+ at different temperatures. The initial concentration of these metal ions and the dosage of functional nanocomposites were 25 and 2.0 mg/mL, respectively.

2.5. Effect of Contact Time and Adsorption Kinetics

Since adsorption kinetics that describes the solute uptake rate and the mechanism of adsorption is one of the important characteristics defining the adsorption efficiency and contact time of the adsorption interaction, the effect of contact time on the adsorption of Pb2+ onto MGO and MGO@PNB was studied. As is shown in Figure 7, the adsorption capacities of Pb2+ onto both MGO and MGO@PNB increase quickly with increasing contact time within the first 4 min and then rise slowly until the adsorption reaches equilibrium after 20 min, suggesting that the prepared MGO@PNB have rapid adsorption abilities toward Pb2+. The initial high adsorption rate may be ascribed to the abundant active sites on the particle surface. On the basis of the above result, a contact time of 20 min was adopted for the subsequent adsorption studies.

Figure 7.

Effect of contact time on adsorption of Pb2+ onto MGO and MGO@PNB. The initial concentration of Pb2+ and the dosage of functional nanocomposites were 50 and 1.5 mg/mL, respectively.

To further investigate the mechanism of the adsorption processes, the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models are used to fit the experimental data.18,64,65 These two kinetic models can be expressed in linear forms as follows:

| 3 |

| 4 |

where qe and qt are the adsorption capacities of Pb2+ at equilibrium state and at any time t, respectively, and k1 and k2 represent the rate constants of pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models, respectively. The fitting of the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models can be checked by plotting ln(qe – qt) against t and t/qt against t (Supporting Information Figure S1) by the linear regression analysis, respectively. And the values of qe and rate constants (k1 and k2) can be determined from the intercept and slope of the linear plots. The corresponding adsorption kinetic parameters of these two kinetic models, including correlation coefficients (R2), k1, k2, and the calculated qe,cal values, are displayed in Table 2. It can be observed that the qe,cal value of the MGO@PNB calculated through the pseudo-second-order model (11.60 mg/g) is much closer to the experimental qe (11.67 mg/g). Besides, R2 (0.9978) of the pseudo-second-order model for MGO@PNB is slightly higher than that of the pseudo-first-order model (0.9932), indicating that the adsorption process follows the pseudo-second-order model rather than the pseudo-first-order model. Therefore, it can be deduced that the Pb2+ adsorption onto the MGO@PNB involves all of the steps of adsorption, including external film diffusion, chemisorption, and internal particle diffusion.18,64,65 Furthermore, the chemisorption between the metal ions and binding sites of adsorbent, which is the main rate-limiting factor and controlled by the supramolecular host–guest interaction of 18-crown-6 toward Pb2+ in this system, dominates the Pb2+ adsorption process of MGO@PNB.27,63

Table 2. Adsorption Kinetic Parameters of MGO and MGO@PNB toward Pb2+ at 25 °C.

| pseudo-first-order model |

pseudo-second-order model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adsorbent | qe,exp (mg/g) | qe,cal (mg/g) | k1 | R2 | qe,cal (mg/g) | k2 | R2 |

| MGO | 3.35 | 1.01 | 0.317 | 0.9836 | 3.39 | 1.101 | 0.9994 |

| MGO@PNB | 11.67 | 4.59 | 0.202 | 0.9932 | 11.60 | 0.197 | 0.9978 |

2.6. Effect of Initial Ion Concentrations and Adsorption Isotherms

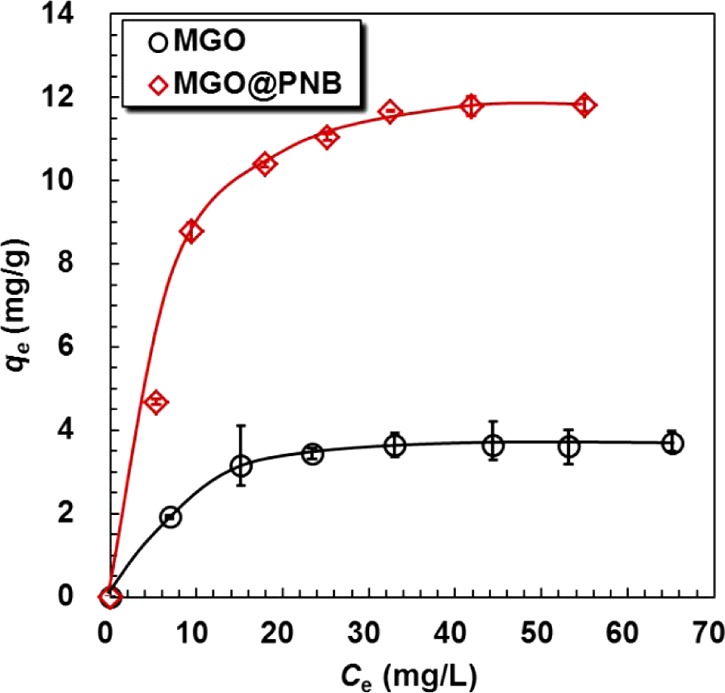

Figure 8 shows the effect of initial ion concentrations on the adsorption of Pb2+ onto MGO and MGO@PNB. The Pb2+ adsorption are highly dependent on the initial ion concentrations and increase with increasing initial Pb2+ concentrations due to excessive active sites available on the adsorbent, which can interact with the relatively insufficient Pb2+ ions in solution. Because the Pb2+ ions in bulk solution are surplus, only parts of them can interact with finite active sites on the adsorbent, thus causing a flat increase until arriving at saturation adsorption at higher ion concentrations. By contrast, the adsorption capacity of Pb2+ onto the MGO is much lower than that of MGO@PNB due to the absence of crown ether units, leading to the inability to form stable 18-crown-6/Pb2+ inclusion complexes.

Figure 8.

Effect of initial ion concentration on the adsorption of Pb2+ onto MGO and MGO@PNB. The dosage of functional nanocomposites was 1.5 mg/mL, and the operation temperature was 25 °C.

The equilibrium adsorption isotherm can provide some important information about the surface properties of adsorbents, the adsorption behaviors, and the design of adsorption systems, which reflects the relationship between the amount of adsorbate uptaken by the adsorbents and the concentration of adsorbate remaining in solution when the adsorption process reaches equilibrium.18,66Figure 9 shows the adsorption isotherms of Pb2+ by MGO and MGO@PNB. The adsorption capacities of Pb2+ onto MGO and MGO@PNB increase initially and then gradually reach saturation adsorption. To make a further investigation on both the adsorption mechanism and affinity of the adsorbent, the experimental equilibrium data of Pb2+ adsorption onto MGO and MGO@PNB at pH 5.0 and 25 °C are fitted by the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models.18,66 The Langmuir isotherm model is often applicable that the adsorption is localized on a monolayer and occurs on a homogeneous surface with all of the adsorption sites having equal adsorbate affinity, whereas the Freundlich isotherm model presumes that the multilayer of the adsorption process occurs on a heterogeneous adsorption surface.18,66 These two isotherm models can be expressed in linear forms by the following equations

| 5 |

| 6 |

where qe and qm (mg/g) are the equilibrium and maximum adsorption capacities of the adsorbent, respectively; Ce (mg/L) is the equilibrium solution concentration of Pb2+; KL (L/mg) represents the Langmuir constant, which relates to the affinity of the binding sites; and KF and n are the Freundlich constants that represent the adsorption capacity and adsorption intensity, respectively. On the basis of the above equations, the values of qm and KL for the Langmuir model can be determined from the slope and intercept of the linear plot of Ce/qe versus Ce, whereas the values of KF and 1/n for the Freundlich model can be determined from the slope and intercept of the linear plot of ln qe versus ln Ce (Supporting Information Figure S2). The relevant parameters calculated from the Langmuir and Freundlich models are listed in Table 3. The correlation coefficients of MGO@PNB (R2 = 0.9893) and MGO (R2 = 0.9945) obtained from the Langmuir isotherm model are very close to 1 and much higher than those from the Freundlich isotherm model, indicating that the Langmuir isotherm fits better with the experimental adsorption data. Besides, the maximum monolayer adsorption capacity (qmax) values for MGO@PNB and MGO calculated from the Langmuir isotherm are 11.76 and 3.66 mg/g, respectively, which are all in accordance with the experimental values (11.82 and 3.70 mg/g, respectively). This suggests again that the Pb2+ adsorption onto MGO@PNB and MGO is a monolayer adsorption and follows the Langmuir isotherm.

Figure 9.

Adsorption isotherms of Pb2+ by MGO and MGO@PNB. The dosage of nanocomposites was 1.5 mg/mL, and the operation temperature was 25 °C.

Table 3. Langmuir and Freundlich Isotherm Parameters for Pb2+ Adsorption by MGO and MGO@PNB at 25 °C.

| Langmuir model |

Freundlich model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adsorbent | qmax (mg/g) | KL (L/mg) | RL | R2 | n | KF | R2 |

| MGO | 3.66 | 0.199 | 0.201–0.334 | 0.9954 | 3.786 | 1.350 | 0.7879 |

| MGO@PNB | 11.76 | 0.149 | 0.283–0.441 | 0.9893 | 2.800 | 3.256 | 0.7966 |

Moreover, the essential feature of the Langmuir isotherm can be expressed in terms of a dimensionless constant separation factor (RL), which is used to evaluate the feasibility of adsorption onto an adsorbent.59 The RL can be calculated by the following equation:

| 7 |

where C0 (mg/L) is the initial ion concentrations in aqueous solution and KL (L/mg) is the Langmuir constant. The value of RL indicates the type of the isotherm to be unfavorable (RL > 1), linear (RL = 1), favorable (0 < RL < 1), or irreversible (RL = 0).59 The RL values of Pb2+ adsorption onto MGO@PNB and MGO ranged from 0.201 to 0.441, indicating that the Pb2+ adsorption onto MGO@PNB and MGO is a favorable process.

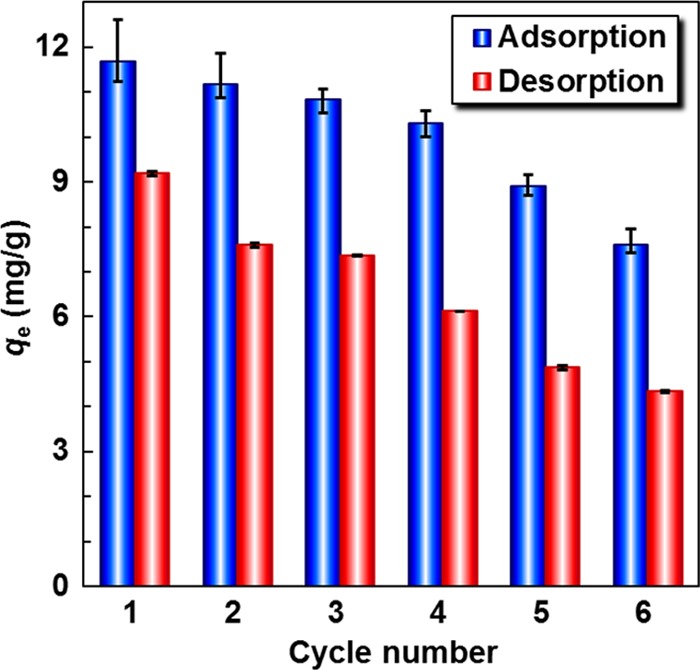

2.7. Regeneration of MGO@PNB

The regeneration and recycling of an adsorbent is very important for its practical applications. As shown in Figure 3e, the Fe3O4 NPs loaded on the MGO@PNB endow them with convenient separability from aqueous solution under an external magnetic field. Thus, the regeneration of Pb2+-loaded MGO@PNB can be easily implemented by using a magnet and then flushing alternatively with hot water (70 °C) and cold water (25 °C). The Pb2+ adsorption/desorption from the MGO@PNB are performed for six successive cycles, and the results are shown in Figure 10. The desorption capacities of Pb2+-loaded MGO@PNB are slightly lower than the adsorption capacities for each cycle. This is due to that some parts of Pb2+ adsorbed on the MGO@PNB cannot desorb from the cavities of crown ether during the regeneration process and the amount of MGO@PNB would also incur loss during the washing process. However, the Pb2+ adsorption capacities of MGO@PNB at 25 °C only lose about 20% after six successive adsorption/desorption cycles, indicating that the as-fabricated MGO@PNB have excellent recyclability. Compared to the commonly used regeneration methods using strong acid and/or strong base or inorganic salt solutions through repeated ultrasonication,16,18−22,67−69 the proposed strategy for the regeneration of MGO@PNB herein is not only much simpler but also more environmentally friendly.

Figure 10.

Adsorption and desorption ability of MGO@PNB toward Pb2+ in six successive cycles. The initial Pb2+ concentration and the dosage of nanocomposites were 50 and 1.5 mg/mL, respectively.

We also compare the adsorption performances of the MGO@PNB toward Pb2+ with the traditional adsorbents reported recently,16,18−22,67 and the results are listed in Table 4. Although those traditional adsorbents show higher adsorption capacities for single-lead ion system than the MGO@PNB developed in this work, they have some evident drawbacks, such as lack of ion selectivity and sensitivity of Pb2+, operational complexity, and environmental unfriendliness upon regenerating those adsorbents. This limits the practical applications of these materials to some degree. By contrast, the as-prepared MGO@PNB demonstrate highly thermosensitive ion-recognition selectivity of Pb2+ among the coexisting metal ions. Most importantly, the Pb2+-loaded MGO@PNB can be easily regenerated by alternatively washing with hot/cold water instead of using strong acids, strong bases, and/or inorganic salt solutions,16,18−22,67 which is much simpler and environmentally friendly compared to the commonly regenerated techniques of adsorbents. And the low adsorption capacity of MGO@PNB toward Pb2+ is because the incorporation amount of crown ether units on the functional graphene nanocomposites is not high. Further studies on improving the adsorption capacity of Pb2+ are being carried out by our group.

Table 4. Comparison of Pb2+ Adsorption on Various Adsorbents.

| adsorbent | qmax (mg/g) | regeneration method | refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| sludge-derived biochar | 30.88 | washing with HCit, EDTA, and HCl | (16) |

| mango peel waste | 97.07 | washing with HCI | (18) |

| phosphorylated magnetic chitosan composite | 151.06 | washing with HCI | (19) |

| magnetic anaerobic granule sludge/chitosan composite | 97.97 | washing with Na2EDTA | (20) |

| magnetic hydroxypropyl Chitosan/oxidized multiwalled CNTs | 101.10 | washing with NaOH | (21) |

| graphenes magnetic material | 27.95 | washing NaOH and HCl | (22) |

| poly(AMPSG/AAc/NVP/HEMA) hydrogel | 22.73 | washing with HNO3 | (67) |

| MGO@PNB | 11.76 | washing with hot/cold water | this study |

Besides, to further investigate the chemical stability of the MGO@PNB, the degree of iron leaching into the aqueous solution was measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) after each adsorption/regeneration process mentioned above.70 The measured and calculated values of iron leaching from MGO@PNB are listed in Table 5. The theoretical value is calculated to be ≤11.20 μg/L since the content of iron impurity is ≤0.00002% for HNO3, which is used to adjust the pH value of aqueous solutions, whereas the measured value in aqueous solution after each regeneration cycle is in the range of 8.11–10.52 μg/L, indicating the excellent chemical stability of the MGO@PNB. All of those results indicate that the developed MGO@PNB herein can be used for specific recognition and removal of Pb2+ from aqueous environment.

Table 5. Measured and Calculated Values of Iron Leaching for Magnetic MGO@PNB.

| measured values after each cycle (μg/L) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | calculated value (μg/L) |

| 9.68 ± 1.37 | 9.55 ± 0.17 | 9.06 ± 2.06 | 10.52 ± 0.64 | 8.11 ± 0.03 | ≤11.20 |

3. Conclusions

In summary, a novel type of smart graphene oxide nanocomposites (MGO@PNB) with excellent magnetism and highly thermosensitive ion-recognition selectivity of Pb2+ has been successfully developed by immobilizing superparamagnetic Fe3O4 NPs and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-benzo-18-crown-6 acrylamide) thermosensitive microgels (PNB) onto the GO using simple one-step solvothermal method and mussel-inspired polydopamine chemistry. The PNB are composed of cross-linked PNIPAM chains with numerous appended 18-crown-6 units. The 18-crown-6 units can selectively recognize and capture Pb2+ in aqueous solution, and the PNIPAM chains serve as a microenvironmental actuator for the inclusion constants of 18-crown-6/Pb2+ complexes. The loaded Fe3O4 NPs endow the MGO@PNB with convenient magnetic separability. The resulted MGO@PNB demonstrate high ion-recognition selectivity of Pb2+ among the coexisting metal ions, including Cr3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Cd2+, and Pb2+, by forming stable 18-crown-6/Pb2+ inclusion complexes and the excellent thermosensitive adsorption ability toward Pb2+ due to the incorporation of PNIPAM functional chains on the MGO. The adsorption process is spontaneous and endothermic and fits well with the pseudo-second-order model and the Langmuir isotherm model. Most importantly, the Pb2+-loaded MGO@PNB can be easily regenerated by alternatively washing with hot/cold water. Such multifunctional graphene nanocomposites developed herein have great potentials in specific recognition and removal of Pb2+ from water environment.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

N-Isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry and purified by recrystallization with a mixture of hexane and acetone (50/50, v/v). Benzo-18-crown-6 acrylamide (B18C6Am) was synthesized from 4-nitro-benzo-18-crown-6 (NB18C6, Sigma-Aldrich) according to ref (26). Graphene oxide (GO) was prepared from graphite powders (325 mesh, Qingdao Huatai Lubricating & Sealing Tech. Co., Ltd.) according to refs47−50. Poly(4-styrenesulfonic acid-co-maleic acid, SS/MA = 3:1) sodium salt (PSSMA, Mw =20 000), tris(hydroxymethyl) methylaminomethane (THAM), and dopamine hydrochloride (DA) were purchased from Aladdin Chemicals. 2,2′-Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), N,N′-methylenediacrylamide (MBA), sodium acetate (NaAc), and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) were obtained from Chengdu Kelong Chemicals, and AIBN was recrystallized with ethanol before use. All other chemicals were of analytical grade and used as received. Deionized water (18.2 MΩ, 25 °C) from a Milli-Q plus purification system (Millipore) was used throughout the experiments.

4.2. Synthesis of MGO@PNB

MGO@PNB were fabricated by immobilizing PNB onto MGO using the adhesion property of DA under weak alkaline condition (pH = 8.5).52−55 MGO and PNB were synthesized according to refs47−51. The detailed synthesis process is shown in the Supporting Information.

4.3. Characterizations

The morphologies and microstructures of functional nanocomposites were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-2010, JEOL, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 120 kV. Samples dispersed at an appropriate concentration were dropped onto a carbon-coated Cu grid, followed by air drying. The chemical structures and compositions of functional nanocomposites were characterized by a Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrometer (IR 200, Thermo Nicolet). The hydrodynamic sizes of PNB were tested by a dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument (Zetasizer Nano-ZS, Malvern Instruments, UK) with a scattering angle of 90°. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the functional nanocomposites was performed on a Mettler TGA/SDTA851e° (Switzerland) at a heating rate of 5 °C/min from 20 to 650 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. The magnetism of functional nanocomposites was measured by a vibrating sample magnetometer on a model 6000 physical property measurement system (Quantum Design). The stabilities of functional nanocomposites during adsorption processes were measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Thermo Fisher).

4.4. Adsorption Experiments

To study the thermosensitive adsorption behaviors and the adsorption thermodynamics of MGO@PNB toward metal ions, three typical operating temperatures, including 25 °C (lower than the VPTT of PNB), 45 °C (slightly higher than the VPTT of PNB), and 65 °C (higher than the VPTT of PNB), were chosen as the investigated temperatures. In detail, 15 mg of MGO@PNB (or MGO) was added in the preheated vials contained 10 mL of Pb2+ solutions at 25 °C. The initial Pb2+ concentration was 50 mg/L, and the pH values were adjusted to 5.0 with a negligible volume of 10 wt % HNO3. Then, the vials were sealed and placed in a thermostatic shaker at different temperatures (25, 45, and 65 °C) and shaken under 150 rpm for 20 min to ensure reaching adsorption equilibrium. After that, the metal ions-loaded MGO@PNB were separated with a magnet and the supernatant was drawn out and filtrated with a 0.22 μm micropore membrane to ensure the safe use of subsequent analytical instrument. The Pb2+ concentrations before and after interaction with functional nanocomposites were analyzed by ICP-MS. Besides, the blank aqueous solutions without adding MGO@PNB were also conducted at each stage of the experiment.

The ion selectivity of MGO@PNB was investigated by batch adsorption experiments at a fixed pH value in mixtures of metal ions containing Pb2+, Cr3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Cd2+. The initial concentrations of these metal ions and pH values in aqueous solutions were all 25 mg/L and 5.0, respectively. Then, 20 mg of MGO@PNB was added in vials that contained 10 mL of the aforementioned metal ions solutions. The vials were sealed and vibrated in a thermostatic shaker under 150 rpm at different temperatures (25, 45, and 65 °C) for 20 min, and the concentrations of Pb2+, Cr3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Cd2+ before and after interaction with the functional nanocomposites were measured with ICP-MS. To confirm that the ion selectivity of the MGO@PNB toward Pb2+ was due to the formation of 18-crown-6/Pb2+ complexes, the PNB-free MGO and the crown ether units-free MGO@PN were used to interact with the metal ions solutions with the same procedure as described above.

The adsorption kinetics were studied by batch adsorption experiments with 15 mg of MGO@PNB and an initial Pb2+ concentration of 50 mg/L at 25 °C and pH 5.0 to evaluate the minimum contact time required for reaching adsorption equilibrium. Aqueous samples after interaction with functional nanocomposites were measured at determined time intervals. To study the effect of initial ion concentrations on the adsorption of Pb2+, 15 mg of MGO@PNB was added in vials that contained 10 mL of Pb2+ solutions with different concentrations ranging from 0 to 70 mg/L. To assess the regeneration performance of the MGO@PNB, desorption experiments were carried out by increasing the operating temperature and washing with deionized water in a thermostatic shaker for 10 h; then, the magnetically collected MGO@PNB were washed alternately with hot/cold water several times, and then used for the next cycle. The adsorption/desorption capacities of Pb2+ were tested in the same way as described above.

The equilibrium adsorption capacities of functional nanocomposites toward metal ions (qe, mg/g) were calculated from the following equation:

| 8 |

where C0 and Ce are the initial and equilibrium concentrations (mg/L) of Pb2+ in solution, respectively; qe is the amount of Pb2+ adsorbed onto the MGO@PNB (mg/g) after equilibrium, V is the volume of metal-ion solutions (L), and m is the mass of functional nanocomposites (g). All of the adsorption experiments were performed at least thrice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21676219), the Sichuan Province Science and Technology Support Program (2016GZ0280), and the China Scholarship Council Program (201800850002). L.-T. Pan acknowledges the support of the Innovative Research Program for Students of Southwest Minzu University (CX2017SZ008).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b03539.

Synthesis of MGO, PNB, and MGO@PNB; fitting of pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models; and fitting of Langmuir and Freundlich models for Pb2+ adsorption (PDF)

Author Contributions

† L.P. and G.Z. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kim H. N.; Ren W. X.; Kim J. S.; Yoon J. Fluorescent and colorimetric sensors for detection of lead, cadmium, and mercury ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3210–3244. 10.1039/c1cs15245a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madadrang C. J.; Kim H. Y.; Gao G. H.; Wang N.; Zhu J.; Feng H.; Gorring M.; Kasner M. L.; Hou S. F. Adsorption behavior of EDTA-graphene oxide for Pb (II) removal. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 1186–1193. 10.1021/am201645g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge F.; Li M. M.; Ye H.; Zhao B. X. Effective removal of heavy metal ions Cd2+, Zn2+, Pb2+, Cu2+ from aqueous solution by polymer-modified magnetic nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 211-212, 366–372. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T.; Dong S. J.; Wang E. A lead(II)-driven DNA molecular device for turn-on fluorescence detection of lead(II) ion with high selectivity and sensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 13156–13157. 10.1021/ja105849m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstraeten S. V.; Aimo L.; Oteiza P. I. Aluminium and lead: molecular mechanisms of brain toxicity. Arch. Toxicol. 2008, 82, 789–802. 10.1007/s00204-008-0345-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg G. F.; Fowler B. A.; Nordberg M.; Friberg L. T.. Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, Boston, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K. H.; Orvig C. Boon and bane of metal ions in medicine. Science 2003, 300, 936–939. 10.1126/science.1083004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S. R.; Tong P.; Li H.; Tang J.; Zhang L. Ultrasensitive electrochemical detection of Pb2+ based on rolling circle amplification and quantum dotstagging. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 42, 608–611. 10.1016/j.bios.2012.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toscano C. D.; Guilarte T. R. Lead neurotoxicity: from exposure to molecular effects. Brain Res. Rev. 2005, 49, 529–554. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilarte T. R.; Toscano C. D.; McGlothan J. L.; Weaver S. A. Environmental enrichment reverses cognitive and molecular deficits induced by developmental lead exposure. Ann. Neurol. 2003, 53, 50–56. 10.1002/ana.10399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Luo F.; Ju X. J.; Xie R.; Sun Y. M.; Wang W.; Chu L. Y. Gating membranes for water treatment: detection and removal of trace Pb2+ ions based on molecular recognition and polymer phase transition. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 9659–9671. 10.1039/c3ta12006f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. Y.; Liu G. C.; Zheng H.; Li F. M.; Ngo H. H.; Guo W. S.; Liu C.; Chen L.; Xing B. S. Investigating the mechanisms of biochar’s removal of lead from solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 177, 308–317. 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.11.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y. W.; Gao B.; Yao Y.; Inyang M.; Zhang M.; Zimmerman A. R.; Ro K. S. Hydrogen peroxide modification enhances the ability of biochar (hydrochar) produced from hydrothermal carbonization of peanut hull to remove aqueous heavy metals: batch and column tests. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 200–202, 673–680. 10.1016/j.cej.2012.06.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nurchi V. M.; Villaescusa I. Agricultural biomasses as sorbents of some trace metals. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008, 252, 1178–1188. 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.09.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rashdi B. A. M.; Johnson D. J.; Hilal N. Removal of heavy metal ions by nanofiltration. Desalination 2013, 315, 2–17. 10.1016/j.desal.2012.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H. L.; Zhang W. H.; Yang Y. X.; Huang X. F.; Wang S. Z.; Qiu R. L. Relative distribution of Pb2+ sorption mechanisms by sludge-derived biochar. Water Res. 2012, 46, 854–862. 10.1016/j.watres.2011.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Lin S.; Chen Z. L.; Megharaj M.; Naidu R. Kaolinite-supported nanoscale zero-valent iron for removal of Pb2+ from aqueous solution: reactivity, characterization and mechanism. Water Res. 2011, 45, 3481–3488. 10.1016/j.watres.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal M.; Saeed A.; Zafar S. I. FTIR spectrophotometry, kinetics and adsorption isotherms modeling, ion exchange, and EDX analysis for understanding the mechanism of Cd2+ and Pb2+ removal by mango peel waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 164, 161–171. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.07.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.; Wang Y.; Li Y.; Wei Q.; Hu L.; Yan T.; Feng R.; Yan L.; Du B. Phosphorylated chitosan/CoFe2O4 composite for the efficient removal of Pb(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solution: adsorption performance and mechanism studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 277, 181–188. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.12.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T.; Han X.; Wang Y.; Yan L.; Du B.; Wei Q.; Wei D. Magnetic chitosan/anaerobic granular sludge composite: synthesis, characterization and application in heavy metal ions removal. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 508, 405–414. 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Shi L.; Gao L.; Wei Q.; Cui L.; Hu L.; Yan L.; Du B. The removal of lead ions from aqueous solution by using magnetic hydroxypropyl chitosan/oxidized multiwalled carbon nanotubes composites. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 451, 7–14. 10.1016/j.jcis.2015.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X.; Du B.; Wei Q.; Yang J.; Hu L.; Yan L.; Xu W. Synthesis of amino functionalized magnetic graphenes composite material and its application to remove Cr(VI), Pb(II), Hg(II), Cd(II) and Ni(II) from contaminated water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 278, 211–220. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J.; Liu S. Y. Engineering responsive polymer building blocks with host-guest molecular recognition for functional applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2084–2095. 10.1021/ar5001007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis F.; Auger M.; Voyer N. Exploiting peptide nanostructures to construct functional artificial ion channels. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2934–2943. 10.1021/ar400044k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. L.; Gu Q. Y.; Su F. F.; Sun Y. H.; Sun G. B.; Ma S. L.; Yang X. J. Intercalation of azamacrocyclic crown ether into layered rare-earth hydroxide (LRH): secondary host-guest reaction and efficient heavy metal removal. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 14010–14017. 10.1021/ic4017307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X. B.; Liu L. L.; Deng F.; Luo S. L. Novel ion-imprinted polymer using crown ether as a functional monomer for selective removal of Pb(II) ions in real environmental water samples. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 8280–8286. 10.1039/c3ta11098b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. M.; Ju X. J.; Xin Y.; Zheng W. C.; Wang W.; Wei J.; Xie R.; Liu Z.; Chu L. Y. A novel smart microsphere with magnetic core and ion-recognizable shell for Pb2+ adsorption and separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 9530–9542. 10.1021/am501919j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju X. J.; Zhang S. B.; Zhou M. Y.; Xie R.; Yang L.; Chu L. Y. Novel heavy-metal adsorption material: ion-recognition P(NIPAM-co-BCAm) hydrogels for removal of lead(II) ions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 167, 114–118. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. R.; Hu J. Q.; Lu X. H.; Ju X. J.; Liu Z.; Xie R.; Wang W.; Chu L. Y. Insights into the effects of 2:1 “sandwich-type” crown-ether/metal-ion complexes in responsive host-guest systems. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 1696–1705. 10.1021/jp5079423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra E. J.; Blondeau P.; Crespo G. A.; Rius F. X. An effective nanostructured assembly for ion-selective electrodes. An ionophore covalently linked to carbon nanotubes for Pb2+ determination. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 2438–2440. 10.1039/C0CC03639K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.; Wang W.; Ju X. J.; Xie R.; Liu Z.; Yu H. R.; Zhang C.; Chu L. Y. Ultrasensitive microchip based on smart microgel for real-time online detection of trace threat analytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2023–2028. 10.1073/pnas.1518442113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing B.; Zhu W.; Zheng X.; Zhu Y.; Wei Q.; Wu D. Electrochemiluminescence immunosensor based on quenching effect of SiO2@PDA on SnO2/rGO/Au NPs-luminol for insulin detection. Sens. Actuators, B 2018, 265, 403–411. 10.1016/j.snb.2018.03.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X.; Zhang T.; Wu D.; Yan T.; Pang X.; Du B.; Lou W.; Wei Q. Increased electrocatalyzed performance through high content potassium doped graphene matrix and aptamer tri infinite amplification labels strategy: highly sensitive for matrix metalloproteinases-2 detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 94, 694–700. 10.1016/j.bios.2017.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X.; Ma H.; Zhang T.; Zhang Y.; Yan T.; Du B.; Wei Q. Sulfur-doped graphene-based immunological biosensing platform for multianalysis of cancer biomarkers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 37637–37644. 10.1021/acsami.7b13416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherlala A. I. A.; Raman A. A. A.; Bello M. M.; Asghar A. A review of the applications of organo-functionalized magnetic graphene oxide nanocomposites for heavy metal adsorption. Chemosphere 2018, 193, 1004–1017. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.11.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L. M.; Wang Y. G.; Gao L.; Hu L. H.; Yan L. G.; Wei Q.; Du B. EDTA functionalized magnetic graphene oxide for removal of Pb(II), Hg(II) and Cu(II) in water treatment: adsorption mechanism and separation property. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 281, 1–10. 10.1016/j.cej.2015.06.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L. M.; Guo X. Y.; Wei Q.; Wang Y. G.; Gao L.; Yan L. G.; Yan T.; Du B. Removal of mercury and methylene blue from aqueous solution by xanthate functionalized magnetic graphene oxide: sorption kinetic and uptake mechanism. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 439, 112–120. 10.1016/j.jcis.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J. H.; Zhang X. R.; Zeng G. M.; Gong J. L.; Niu Q. Y.; Liang J. Simultaneous removal of Cd(II) and ionic dyes from aqueous solution using magnetic graphene oxide nanocomposite as an adsorbent. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 226, 189–200. 10.1016/j.cej.2013.04.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q.; Zhou Z.; Chen Z. F. Graphene-related nanomaterials: tuning properties by functionalization. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 4541–4583. 10.1039/c3nr33218g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra V.; Park J.; Chun Y.; Lee J. W.; Hwang I.-C.; Kim K. S. Water-dispersible magnetite-reduced graphene oxide composites for arsenic removal. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3979–3986. 10.1021/nn1008897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S. J.; Dong S. J. Graphene nanosheet: synthesis, molecular engineering, thin film, hybrids, and energy and analytical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 2644–2672. 10.1039/c0cs00079e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Zhu W.; Ren X.; Khan M. S.; Zhang Y.; Du B.; Wei Q. Macroporous graphene capped Fe3O4 for amplified electrochemiluminescence immunosensing of carcinoembryonic antigen detection based on CeO2@TiO2. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 91, 842–848. 10.1016/j.bios.2017.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Li Y.; Zhang Y.; Fan D.; Pang X.; Wei Q.; Du B. 3D nanostructured palladium-functionalized graphene-aerogel-supported Fe3O4 for enhanced Ru(bpy)32+-based electrochemiluminescent immunosensing of prostate specific antigen. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 35260–35267. 10.1021/acsami.7b11458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izatt R. M.; Pawlak K.; Bradshaw J. S.; Bruening R. L. Thermodynamic and kinetic data for macrocycle interactions with cations and anions. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 1721–2085. 10.1021/cr00008a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T.; Sato Y.; Yamaguchi T.; Nakao S. -i. Response mechanism of a molecular recognition ion gating membrane. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 3407–3414. 10.1021/ma030590w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T.; Hioki T.; Yamaguchi T.; Shinbo T.; Nakao S.-i.; Kimura S. Development of a molecular recognition ion gating membrane and estimation of its pore size control. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 7840–7846. 10.1021/ja012648x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H. M.; Cao L. Y.; Lu L. H. Magnetite/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites: one step solvothermal synthesis and use as a novel platform for removal of dye pollutants. Nano Res. 2011, 4, 550–562. 10.1007/s12274-011-0111-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ai L. H.; Zhang C. Y.; Chen Z. L. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution by a solvothermal-synthesized graphene/magnetite composite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 192, 1515–1524. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K. F.; Zhu Y. H.; Yang X. L.; Li C. Z. One-pot preparation of graphene/Fe3O4 composites by a solvothermal reaction. New J. Chem. 2010, 34, 2950–2955. 10.1039/c0nj00283f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. R.; Song X. D.; Zhu H. Y.; Cheng C. J.; Yu H. R.; Zhang H. H. Novel smart polymer-brush-modified magnetic graphene oxide for highly efficient chiral recognition and enantioseparation of tryptophan enantiomers. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. 2018, 1, 1074–1083. 10.1021/acsabm.8b00294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M. Y.; Ju X. J.; Fang L.; Liu Z.; Yu H. R.; Jiang L.; Wang W.; Xie R.; Chen Q.; Chu L. Y. A novel, smart microsphere with K+-induced shrinking and aggregating properties based on a responsive host-guest system. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 19405–19415. 10.1021/am505506v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q.; Pan Q. M. Mussel-inspired direct immobilization of nanoparticles and application for oil-water separation. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 1402–1409. 10.1021/nn4052277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. S.; Cao J. M.; Li H.; Li J. Y.; Jin Q.; Ren K. F.; Ji J. Mussel-inspired polydopamine: a biocompatible and ultrastable coating for nanoparticles in vivo. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9384–9395. 10.1021/nn404117j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynge M. E.; van der Westen R.; Postma A.; Stadler B. Polydopamine-a nature-inspired polymer coating for biomedical science. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 4916–4928. 10.1039/c1nr10969c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.; Dellatore S. M.; Miller W. M.; Messersmith P. B. Mussel-inspired surface chemistry for multifunctional coatings. Science 2007, 318, 426–430. 10.1126/science.1147241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer D. R.; Miller D. J.; Freeman B. D.; Paul D. R.; Bielawski C. W. Elucidating the structure of poly(dopamine). Langmuir 2012, 28, 6428–6435. 10.1021/la204831b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Ju X. J.; Xie R.; Liu Z.; Pi S. W.; Chu L. Y. Comprehensive effects of metal ions on responsive characteristics of P(NIPAM-co-B18C6Am). J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 5527–5536. 10.1021/jp3004322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Luo F.; Ju X. J.; Xie R.; Luo T.; Sun Y. M.; Chu L. Y. Positively K+-responsive membranes with functional gates driven by host-guest molecular recognition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 4742–4750. 10.1002/adfm.201201251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J.; Chen Z.; Wang M.; Liu S.; Zhang J.; Zhang J.; Han R.; Xu Q. Adsorption of methylene blue by a high-efficiency adsorbent (polydopamine microspheres): kinetics, isotherm, thermodynamics and mechanism analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 259, 53–61. 10.1016/j.cej.2014.07.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Wang L.; Zhu Y. Decontamination of bisphenol A from aqueous solution by graphene adsorption. Langmuir 2012, 28, 8418–8425. 10.1021/la301476p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin X.; Wei Q.; Yang J.; Yan L.; Feng R.; Chen G.; Du B.; Li H. Highly efficient removal of heavy metal ions by amine-functionalized mesoporous Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 184, 132–140. 10.1016/j.cej.2012.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hay B. P.; Rustad J. R.; Hostetlert C. J. Quantitative structure-stability relationship for potassium ion complexation by crown ethers. A molecular mechanics and ab initio study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 11158–11164. 10.1021/ja00077a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. B.; Song X. D.; Cheng C. J.; Zhao Z. G. Poly(4-styrenesulfonic acid-co-maleic acid)-sodium-modified magnetic reduced graphene oxide for enhanced adsorption performance toward cationic dyes. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 87030–87042. 10.1039/C5RA18255G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y. S. Review of second-order models for adsorption systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 136, 681–689. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y. S.; McKay G. The kinetics of sorption of divalent metal ions onto sphagnum moss peat. Water Res. 2000, 34, 735–742. 10.1016/S0043-1354(99)00232-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.-S.; Zheng T.; Wang P.; Jiang J.-P.; Li N. Adsorption isotherm, kinetic and mechanism studies of some substituted phenols on activated carbon fibers. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 157, 348–356. 10.1016/j.cej.2009.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yetimoğlu E. K.; Fırlak M.; Kahraman M. V.; Deniz S. Removal of Pb2+ and Cd2+ ions from aqueous solutions using guanidine modified hydrogels. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2011, 22, 612–619. 10.1002/pat.1554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.; Hu L.; Wang Y.; Wei Q.; Yan L.; Yan T.; Li Y.; Du B. EDTA modified β-cyclodextrin/chitosan for rapid removal of Pb(II) and acid red from aqueous solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 523, 56–64. 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Hu L.; Zhang G.; Yan T.; Yan L.; Wei Q.; Du B. Removal of Pb(II) and methylene blue from aqueous solution by magnetic hydroxyapatite-immobilized oxidized multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 494, 380–388. 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.01.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi S. S.; Li A.; Wei W.; Feng L.; Zhang G. S.; Chen T.; Zhou X.; Sun H. H.; Ma F. Synthesis of a novel magnetic nano-scale biosorbent using extracellular polymeric substances from Klebsiella sp. J1 for tetracycline adsorption. Bioresource Technol. 2017, 245, 471–476. 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.08.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.