Abstract

The effect of water on the hydrogen abstraction mechanism and product branching ratio of CH3CH2OH + •OH reaction has been investigated at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ//BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory, coupled with the reaction kinetics calculations, implying the harmonic transition-state theory. Depending on the hydrogen sites in CH3CH2OH, the bared reaction proceeds through three elementary paths, producing CH2CH2OH, CH3CH2O, and CH3CHOH and releasing a water molecule. Thermodynamic and kinetic results indicate that the formation of CH3CHOH is favored over the temperature range of 216.7–425.0 K. With the inclusion of water, the reaction becomes quite complex, yielding five paths initiated by three channels. The products do not change compared with the bared reaction, but the preference for forming CH3CHOH drops by up to 2%. In the absence of water, the room temperature rate coefficients for the formation of CH2CH2OH, CH3CH2O, and CH3CHOH are computed to be 5.2 × 10–13, 8.6 × 10–14, and 9.0 × 10–11 cm3 molecule–1 s–1, respectively. The effective rate coefficients of corresponding monohydrated and dihydrated reactions are 3–5 and 6–8 orders of magnitude lower than those of the unhydrated reaction, indicating that water has a decelerating effect on the studied reaction. Overall, the characterized effects of water on the thermodynamics, kinetics, and products of the CH3CH2OH + •OH reaction will facilitate the understanding of the fate of ethanol and secondary pollutants derived from it.

1. Introduction

Environmental and energetic crises have led to the increasing use of ethanol (CH3CH2OH) as one of the environment friendly and renewable biofuels and especially as a fuel additive or extender.1,2 The enhanced use of ethanol is likely to result in its increased release into the atmosphere as unburnt fuel, fugitive emissions, and discharge during its production. Besides, ethanol is also acknowledged as a biogenic volatile organic compound released from living plants with an emission rate of 26 (range, 10–38) Tg year–1, which contributes significantly to a total global ethanol source of 42 (range, 25–56) Tg year–1.1,3 In the atmosphere, most of ethanol is in its ground state and about three-quarters of ethanol are removed by the reaction with hydroxyl radicals in the gaseous and aqueous phases, occurring on a time scale of 4 days, and the remainder is lost through dry deposition and wet scavenging.1,4,5 In the oxidation reaction, a hydroxyl radical can attack and abstract one hydrogen atom of the ground-state ethanol from three different sites (methyl, hydroxyl, and methylene), leading to the formation of different C2H5O isomers.

|

1a |

These C2H5O isomers subsequently undergo atmospheric oxidation with molecular oxygen to generate important secondary pollutants and radicals. Formaldehyde is primarily formed from the β-hydroxyalkyl radical produced from eq 1a through the following processes4,6−8

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

The alkoxy and α-hydroxyalkyl radicals produced via eqs 1b and 1c react with molecular oxygen to form acetaldehyde and the hydroperoxyl radical.4,6,8,9

| 6 |

| 7 |

Further oxidation of acetaldehyde may contribute to the formation of peroxyacetylnitrate and ozone, affecting the partitioning and fate of reactive nitrogen (NOy), therefore increasing the atmospheric oxidizing capacity and also enhancing the role of ethanol as a precursor for the formation of secondary aerosols.4,6,7,10

Given the atmospheric importance of hazardous air pollutants and free radicals generated from the oxidation of C2H5O isomers, the rate coefficients and branching ratios for elementary oxidation (eqs 1a–1c) of ethanol have been extensively studied using experimental and theoretical methods.6,11−15 Dillon et al. obtained an overall reaction rate coefficient (by summing up the rate coefficients of elementary eqs 1a–1c) of 4.0 × 1012 × exp(−42/T) over the temperature range of 216–368 K using a pulsed laser photolysis technique coupled with pulsed laser-induced fluorescence detection of the •OH radical.12 Theoretically, at the CCSD(T)/6-311+G(3df,2p)//MP2/6-311+G(3df,2p) level, the kinetics and mechanisms for •OH + C2H5OH reactions were studied over the temperature range of 200–3000 K by Xu and Lin.16 They found that over 800 K, the predicted overall rate coefficients and the branching ratio of eq 1c were significantly higher than the modeled values by Marinov.17 Sivaramakrishnan and co-workers also studied the •OH oxidation of ethanol and determined Arrhenius expressions of the total and channel-specific rate coefficients over the temperature range of 200–2500 K.13 These studies focused on unhydrated reactions to find accurate Arrhenius expressions for rate coefficients over a wide temperature range. However, water is ubiquitous in the troposphere and because of its ability to act as hydrogen bond acceptor and hydrogen bond donor, it would most likely affect the reaction rates and products’ branching ratio of C2H5O + •OH reaction.

It is evident from the literature that water can easily form hydrogen-bonded complexes with various species in the gas phase and thus dramatically affects their photochemical properties and heterogeneous removal.18−21 These influences have been proven to be catalytic, suppressive, and anti-catalytic effects.22−25 For example, it was shown that the rate coefficient for the self-reaction of HO2 to yield H2O2 and O2 is somewhat faster in the presence of water than in its absence.23 Du and Zhang used the CCSD(T)/6-311++G(3df,3pd)//BH&HLYP/6-311++G(3df,3pd) method to calculate the rate coefficients for H2S and •OH reaction without and with catalyst X (X = H2O, (H2O)2, or H2S) by employing conventional transition-state theory, and they concluded that the presence of X would not play an important role in the oxidation of H2S by •OH radicals under atmospheric conditions.24 Some recent studies, however, showed inhibitive effects of water in hydrogen abstraction reactions involving ClO.26−28 Interestingly, for the reaction of CH3OH + ClO, the effect of water was found to be much more negative on the formation of HOCl + CH2OH than on the formation of HOCl + CH3O.26 For the reaction between the HCOOH···H2O complex and the hydroxy radical, the rate coefficient was 4 times lower than that of the bared reaction.29 It is worth noting that water extensively alters the branching ratio of this reaction. For the bared reaction, the branching ratio of formyl hydrogen abstraction that leads to the formation of HOCO is 7%, while the acidic hydrogen abstraction that produces HCOO accounts for 93%. However, starting from the HCOOH ··· H2O complex, the branching ratio for the formation of HOCO is 90.5% and only 9.5% for HCOO. Recently, a quadratic dependence of the overall reaction rate coefficient on relative humidity (RH) under quasi-real atmospheric conditions was found for the oxidation reaction of C2H5OH by the hydroxyl radical.30 It is clear that water may play different roles on the radical–molecule reactions, change their products’ branching ratios, and thus influence the atmospheric fate of both the radical and pollutant molecules as well as their products. Herein, determining different water effects on reaction rates and product branching ratios of atmospheric-related substances is critical to understanding their atmospheric chemistry. Accordingly, ignoring these water effects could lead to inaccuracies of certain atmospheric models. However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous work has focused on cumulative water effects on branching ratios of the reaction between ethanol and the hydroxyl radical.

Based on the atmospheric significance of ethanol and water, the bared CH3CH2OH + OH reaction and a single water-assisted reaction are explored. We analyze the possible role of water on altering the potential energy surface (PES), the rate coefficients, and the branching ratios of this reaction under different atmospheric temperatures. Besides, given the high water dimer concentration,31,32 recent research studies have also evidenced that two water molecules may play a significant role on the kinetics of various atmospheric reactions.33−35 Hence, the effect of the water dimer is included in the CH3CH2OH + •OH reaction as well.

2. Results and Discussion

In the following, the different reactant intermediates and reaction paths in which the hydroxyl radical abstracts one hydrogen atom from the methyl site, hydroxyl site, and methylene site on ethanol are marked with letters a, b, and c, respectively. Numbers following a letter are used to distinguish the different •OH attacks on the same site. Prereactive complexes, transition states, postreactive complexes, and products of the elementary paths are named by prefixes CR, TS, CP, and Pro, respectively. Besides, in the reactions involving (H2O)n (n = 1–2), W or WW are added as postfixes to denote mono- and dihydrates, respectively.

2.1. PESs for CH3CH2OH + •OH Reaction in the Absence of Water

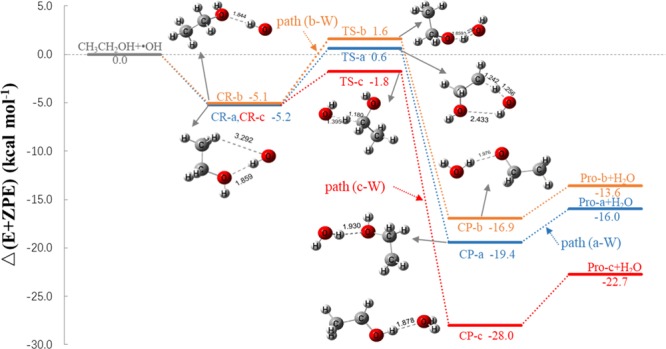

Three elementary reaction paths have been found depending on the ethanol hydrogen [−OH, −CH2– (α-hydrogen), −CH3 (β-hydrogen)] abstracted by the hydroxyl radical. Though ethanol has three conformational structures,15 only the lowest energy ones along three reaction paths are shown in Figure 1. Here, this reaction takes place by the formation of two types of prereactive complexes (transconformation for CR-a and CR-c, and gauche conformation for CR-b), in which a hydrogen bond is formed between the oxygen atom of ethanol and the hydrogen atom on the hydroxyl radical.15,36 The length of the hydrogen bond is 1.9 Å in the prereactive transconformation, which is in agreement with the corresponding value in the previous study.14 Path (a) and path (c) both start with the formation of the same prereactive complex, CR-a, formed with −5.2 kcal mol–1 binding energy (Table 1). CR-a rearranges through the TS-a transition-state configuration located at 0.6 kcal mol–1 above the initial reactants to form the postreactive complex CH2CH2OH···H2O. Path (c) proceeds through the TS-c transition state formed with −1.8 kcal mol–1 energy, 2.4 kcal mol–1 lower than the TS-a energy to form the postreactive complex CH3CHOH···H2O. The prereactive complex CR-b in path (b) is formed with −5.1 kcal mol–1 binding energy and the corresponding transition state is located at 1.6 kcal mol–1 above the reactants. The energy barrier for this path is 6.7, 0.9, and 3.3 kcal mol–1 higher than the energy barriers of path (a) and path (c), respectively. The high barrier might lead CH3CH2O formation kinetically unfavorable.37 These energy barriers are within 1 kcal mol–1 similar to the corresponding values obtained at the CCSD(T)/6-311+G(3df,2p)//MP2/6-311+G(3df,2p) level of theory.16 However, larger values [9.1, 9.5, and 7.0 kcal mol–1 for path (a), path (b), and path (c), respectively] were reported in another study that used the CCSD(T)//BH&HLYP/6-311G(d,p) method.14 The relative energies of CH2CH2OH + H2O, CH3CH2O + H2O, and CH3CHOH + H2O formation are −15.6, −13.6, and −22.7 kcal mol–1, respectively, which is in good agreement with other theoretical values of −15.5, −13.3, and −22.9 kcal mol–1 reported previously.16 These values are within ∼2 kcal mol–1 similar to the corresponding experimental values, 13.05 ± 0.09, −13.84 ± 0.65, and −25.79 ± 0.91 kcal mol–1, respectively.38,39 In terms of the Gibbs free energy change at 1 atm and 298.2 K, the formation of CH3CHOH + H2O [path (c)] is the most energetically favorable with ΔG = −24.2 kcal mol–1. The formation of CH3CHOH + H2O was found to be the predominant hydrogen abstraction reaction at all temperatures.6,13,14,16

Figure 1.

Schematic PES and geometries of the stationary points for the CH3CH2OH + •OH reaction, calculated at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ//BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory.

Table 1. ZPEs, Relative Energies [ΔE and Δ(E + ZPE)], Relative Enthalpies (ΔH at 298 K), and Relative Gibbs Free Energies (ΔG at 298 K) for the CH3CH2OH + •OH Reactiona,b.

| compounds | ZPE | ΔE | Δ(E + ZPE) | ΔH298K | ΔG298K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH3CH2OH + •OH | 57.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| CR-a | 59.1 | –7.0 | –5.2 | –3.8 | 2.8 |

| TS-a | 55.8 | 2.1 | 0.6 | –1.8 | 7.3 |

| CP-a | 57.6 | –19.8 | –19.4 | –18.7 | –13.7 |

| Pro-a + H2O | 56.0 | –14.7 | –16.0 | –16.8 | –18.1 |

| CR-b | 59.0 | –6.8 | –5.1 | –3.6 | 2.9 |

| TS-b | 55.6 | 3.3 | 1.6 | –1.0 | 7.9 |

| CP-b | 57.7 | –17.4 | –16.9 | –16.3 | –11.1 |

| Pro-b + H2O | 55.7 | –12.1 | –13.6 | –14.8 | –16.0 |

| CR-c | 59.1 | –7.0 | –5.2 | –3.8 | 2.9 |

| TS-c | 55.9 | –0.5 | –1.8 | –3.8 | 4.4 |

| CP-c | 58.0 | –28.8 | –28.0 | –26.8 | –21.5 |

| Pro-c + H2O | 56.5 | –22.0 | –22.7 | –23.1 | –24.2 |

All units are kcal mol–1.

ZPE, the H and G corrections are calculated at the BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory. The electronic energy values are obtained at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ//BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory.

2.2. PESs for the CH3CH2OH + •OH Reaction in the Presence of One Water Molecule

The PES for the hydrogen abstraction reaction in the presence of one water molecule (Figures 2 and S1 in the Supporting Information) appears to be more complicated than that of the naked reaction due to more complex interactions between the three participating species, though the final products do not change. The geometries of the stationary points involved in Figure 2 are provided in Figure 3, while corresponding zero-point energy (ZPE), relative energies, enthalpies, and Gibbs free energies can be found in Table 2. Because the possibility of the simultaneous collision of separated ethanol, the hydroxyl radical and water molecule is extremely low, and a more likely scenario is that the reaction involving one water molecule would initially occur through the formation of a two-body complex, followed by its further collision with the third body in the reaction system to form the ternary prereactive complex.35,40 The most likely two-body complexes to form first are •OH···H2O, CH3CH2OH···H2O, and H2O···CH3CH2OH.

Figure 2.

Schematic PES for the CH3CH2OH + •OH + H2O reaction through path (a1-W), path (b-W), and path (c1-W) calculated at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ//BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory.

Figure 3.

Geometries of the stationary points in the CH3CH2OH + •OH + H2O reaction through path (a1-W), path (b-W), and path (c1-W), optimized at the BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory. Bond distances are given in Å.

Table 2. ZPEs, Relative Energies [ΔE and Δ(E + ZPE)], Relative Enthalpies (ΔH at 298 K), and Relative Gibbs Free Energies (ΔG at 298 K) for the CH3CH2OH + •OH Reaction in the Presence of One Water Moleculea,b.

| compounds | ZPE | ΔE | Δ(E + ZPE) | ΔH298K | ΔG298K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH3CH2OH + •OH + H2O | 71.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| •OH···H2O + CH3CH2OH | 73.1 | –5.9 | –3.9 | –2.5 | 3.4 |

| CH3CH2OH···H2O + •OH | 72.6 | –5.3 | –3.7 | –2.2 | 4.1 |

| H2O···CH3CH2OH + •OH | 73.0 | –6.3 | –4.4 | –2.7 | 4.2 |

| CR-a1-W | 75.2 | –14.8 | –10.7 | –7.5 | 8.6 |

| TS-a1-W | 72.1 | –6.7 | –5.7 | –6.3 | 11.9 |

| CP-a1-W | 74.4 | –31.1 | –27.8 | –25.1 | –9.8 |

| CR-a2-W | 75.5 | –16.2 | –11.8 | –8.6 | 7.5 |

| TS-a2-W | 72.7 | –8.1 | –6.5 | –6.8 | 11.9 |

| CP-a2-W | 74.5 | –31.3 | –28.0 | –25.2 | –9.9 |

| Pro-a + 2H2O | 69.9 | –14.7 | –16.0 | –16.8 | –18.1 |

| CR-b-W | 75.5 | –16.3 | –11.9 | –8.7 | 7.5 |

| TS-b-W | 71.9 | –4.6 | –3.8 | –4.4 | 13.0 |

| CP-b-W | 74.4 | –26.2 | –22.9 | –20.2 | –5.2 |

| Pro-b + 2H2O | 69.6 | –12.1 | –13.6 | –14.8 | –16.0 |

| CR-c1-W | 75.1 | –14.9 | –10.9 | –7.7 | 6.9 |

| TS-c1-W | 72.2 | –10.0 | –8.9 | –9.3 | 8.6 |

| CP-c1-W | 75.0 | –38.9 | –35.1 | –31.8 | –16.3 |

| CR-c2-W | 75.4 | –16.3 | –12.0 | –8.8 | 7.3 |

| TS-c2-W | 73.6 | –10.7 | –8.2 | –7.3 | 10.7 |

| CP-c2-W | 75.1 | –38.6 | –34.6 | –31.4 | –15.2 |

| Pro-c + 2H2O | 70.4 | –22.0 | –22.7 | –23.1 | –24.2 |

All units are kcal mol–1.

ZPE, the H and G corrections are calculated at the BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory. The electronic energy values are obtained at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ//BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory.

The OH···H2O complex results from the interaction between the hydrogen atom of OH and the oxygen atom of water, forming a hydrogen bond with a length of 1.9 Å. This complex is formed with −3.9 kcal mol–1 binding energy. Both the energy and geometry of •OH···H2O exhibit excellent uniformity with the results of previous studies.24,29,41 The binary complexes CH3CH2OH···H2O and H2O···CH3CH2OH are formed with −3.7 and −4.4 kcal mol–1 binding energies, respectively. They differ from each other by the type of the hydrogen bond formed within their structures. In the CH3CH2OH···H2O complex, water acts as the hydrogen bond acceptor, forming a 2.0 Å hydrogen bond with the hydrogen atom of the hydroxyl group, whereas a 1.9 Å hydrogen bond is formed between one hydrogen atom of water and the oxygen atom of ethanol in the H2O···CH3CH2OH complex.

The further reactions of •OH···H2O, CH3CH2OH···H2O, and H2O···CH3CH2OH with the third species are named channel 1, channel 2, and channel 3, respectively. These three channels give rise to five different paths that ultimately form CH2CH2OH + 2H2O, CH3CHOH + 2H2O, and CH3CH2O + 2H2O.

The interaction of the CH3CH2OH molecule with the •OH···H2O binary complex as well as the interaction between the •OH radical and H2O···CH3CH2OH complex both lead to CR-a1-W, following path (a1-W). Compared with CR-a in path (a), the newly formed hydrogen bond (1.8 Å) between one hydrogen atom of water and the oxygen atom of ethanol leads to the cyclic structure of CR-a1-W. The computed formation energy of CR-a1-W is −10.7, 5.5 kcal mol–1 lower than CR-a in path (a). CR-a1-W subsequently isomerizes to the corresponding postreactive complex CP-a1-W via the TS-a1-W transition state, where the oxygen of the hydroxyl radical directly abstracts one of the β-hydrogen in the methyl group. The structure of TS-a1-W is more compact than the CR-a1-W structure, and it is located at 5.7 kcal mol–1 energy below the separated reactants. CP-a1-W has a six-membered ring structure stabilized by three hydrogen bonds between two water molecules and the CH2CH2OH residue. The energy barrier of this path is 0.8 kcal mol–1 lower than that in path (a).

The •OH association with CH3CH2OH···H2O forms a six-membered ring-like CR-a2-W ternary complex through path (a2-W) (see Figure S1). This complex is stabilized by three hydrogen bonds where •OH, water, and ethanol all act as hydrogen bond acceptors and donors simultaneously. CR-a2-W is 1.1 kcal mol–1 more stable than CR-a1-W, which is stabilized by only two hydrogen bonds and a weak C···H···O interaction. CR-a2-W rearranges through a TS-a2-W transition-state configuration that lies below the reactants, with an eight-membered ring structure and predicted to be formed with −6.5 kcal mol–1 energy. Despite the intermolecular distances among CH3CH2OH, •OH, and H2O being shorter in TS-a1-W than in TS-a2-W, the energy of the latter is 0.8 kcal mol–1 lower than that of the former, clearly indicating that the oxygen of water is a much better hydrogen bond acceptor than the oxygen of ethanol, while water also acts as a hydrogen bond donor to the hydroxyl radical. CR-a2-W overcomes an energy barrier of 5.3 kcal mol–1 to form the CP-a2-W product complex, which further releases the same final products as in path (a1-W).

For hydroxylic hydrogen abstraction, the ternary prereactive complex CR-b-W can be first formed through the three above channels. Water and ethanol act as the hydrogen acceptor and donor simultaneously in its six-membered ring structure, like the interaction between CH3OH, •OH, and H2O.40 The 2.1 Å hydrogen bond between oxygen in the hydroxyl radical and hydrogen on the hydroxyl site of ethanol indicates that the hydroxyl radical is in the favored position to abstract the hydroxyl hydrogen as in the CR-b prereactive complex. However, the energy barrier height to overcome by CR-b-W to form CH3CH2O through path (b-W) is 1.4 kcal mol–1 higher than in the corresponding barrierless path (b). This indicates that a single water hampers the abstraction process of hydroxylic hydrogen by the hydroxyl radical. Different from CP-a1-W with a six-membered ring structure held by three hydrogen bonds, the CP-b-W formed in path (b-W) has a seven-membered cyclic structure with a formation energy of −22.9 kcal mol–1. It is stabilized by one hydrogen bond (1.9 Å) formed between the oxygen atom of ethanol and the hydrogen of initially added water and a new but weak interaction (2.5 Å) between oxygen of newly formed water and the α-hydrogen of the CH3CH2O residue. The results suggest that the formation of postreactive complex CP-b-W is structurally and energetically advantageous for the formation of CH3CH2O + 2H2O final products.

The reorganization of hydrogen bonds between the three abovementioned binary complexes and the third species give rise to CR-c1-W.25,42 Instead of acting as the hydrogen bond acceptor for the hydrogen of •OH in CR-c, the oxygen atom of ethanol forms a 1.8 Å hydrogen bond with the hydrogen of water. The hydrogen of •OH then binds with the oxygen of water. Besides these two hydrogen bonds, another weak interaction (3.1 Å) exists between ethanol α-H and the oxygen in the hydroxyl radical. This arrangement may facilitate the hydrogen abstraction from methylene by the hydroxyl radical via the TS-c1-W transition state, as evidenced by the decreased energy barrier relative to that in path (c). Contrary to the seven-membered ring-like structure of TS-c1-W, CP-c1-W adopts a six-membered ring structure, where a new hydrogen bond is formed through interaction of the hydroxylic oxygen of ethanol and the hydrogen of water. The energy barrier for this path (2.0 kcal mol–1) is 3.0 kcal mol–1 lower than that of path (a1-W).

Another path leading to the CH3CHOH + 2H2O products is path (c2-W), as shown in Figure S1. The prereactive CR-c2-W complex in this path is formed by the H2O···CH3CH2OH + •OH reaction. It contains similar geometrical features as CR-a2-W with a three-hydrogen bonded cyclic structure. The abstraction of α-H by the hydroxyl radical in this path occurs through the TS-c2-W transition state with a calculated energy barrier of 3.8, 1.8 kcal mol–1 higher than that in path (c1-W). This energy difference is the result of the difference in hydrogen bond interactions in TS-c1-W and TS-c2-W structures. The corresponding postreactive complexes CP-c1-W and CP-c2-W contain six-membered ring structures in their configurations. CP-c1-W lies 35.1 kcal mol–1 below the isolated reactants, 0.5 kcal mol–1 above CP-c2-W. Therefore, given also the low energy barrier of path (c1-W), it is reasonable to conclude that path (c1-W) is more favorable than path (c2-W). Hence, for further analysis of the effect of water on the reaction kinetics, solely, path (c1-W) will be considered.

2.3. PESs for CH3CH2OH + •OH Reaction in the Presence of Two Water Molecules

Based on the multistep mechanism,43−45 the cyclic ternary complexes CH3CH2OH···H2O···H2O and •OH····H2O···H2O with binding energies of −12.3 and −10.5 kcal mol–1, respectively, can form when two water molecules are involved. These complexes can collide with •OH and CH3CH2OH, respectively to initiate the reaction. The interplay of the H2O···CH3CH2OH cluster and •OH···H2O cluster is also estimated to generate the same final products as the two abovementioned channels. Thus, the reaction between ethanol and •OH in the presence of two water molecules could proceed through these three entrance channels, labeled as channel 4, channel 5, and channel 6, respectively. These three channels give rise to six paths [path (a1-WW) and path (a2-WW) for β-hydrogen abstraction, path (c1-WW) and path (c2-WW) for α-hydrogen abstraction, and path (b1-WW) and path (b2-WW) for hydroxylic hydrogen abstraction]. The stationary points in these paths adopt more complicated structures, whose formations are energetically much more favorable than those of corresponding unhydrated complexes. This may suggest that water acting as a hydrogen bond acceptor and donor in a cyclic structure has the capability to stabilize complexes. According to the Gibbs free energy changes in Table 3, the stationary points in the paths that lead to the same products almost energetically degenerate, despite the relative positions of ethanol, water, and •OH radical being different. Hence, only representative paths (a1-WW), (b1-WW), and (c2-WW) are discussed and related PES are shown in Figure 4, while the structures of all intermediate species involved in Figure 4 are given in Figure 5. The PES and geometric information for other paths can be found in Figures S2 and S3 in the Supporting Information.

Table 3. ZPEs, Relative Energies [ΔE and Δ(E + ZPE)], Relative Enthalpies (ΔH at 298 K), and Relative Gibbs Free Energies (ΔG at 298 K) for the CH3CH2OH + •OH Reaction in the Presence of Two Water Moleculesa,b.

| compounds | ZPE | ΔE | Δ(E + ZPE) | ΔH298K | ΔG298K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH3CH2OH + •OH + 2H2O | 85.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| CH3CH2OH···H2O···H2O + •OH | 89.7 | –17.0 | –12.3 | –8.7 | 8.1 |

| •OH···H2O···H2O + CH3CH2OH | 90.0 | –15.5 | –10.5 | –7.2 | 8.5 |

| H2O···CH3CH2OH + •OH···H2O | 88.9 | –12.2 | –8.3 | –5.3 | 7.7 |

| CR-a1-WW | 92.0 | –28.3 | –21.3 | –16.2 | 9.7 |

| TS-a1-WW | 89.2 | –20.4 | –16.2 | –14.6 | 14.0 |

| CP-a1-WW | 91.0 | –43.4 | –37.4 | –32.7 | –8.0 |

| CR-a2-WW | 92.0 | –28.1 | –21.1 | –16.0 | 9.7 |

| TS-a2-WW | 89.2 | –19.9 | –15.6 | –14.0 | 13.9 |

| CP-a2-WW | 90.9 | –42.7 | –36.8 | –32.2 | –7.9 |

| Pro-a + 3H2O | 83.7 | –14.7 | –16.0 | –16.8 | –18.1 |

| CR-b1-WW | 92.0 | –28.2 | –21.1 | –16.0 | 9.6 |

| TS-b1-WW | 88.5 | –16.0 | –12.5 | –11.3 | 15.6 |

| CP-b1-WW | 90.7 | –35.6 | –29.9 | –25.3 | –1.4 |

| CR-b2-WW | 91.9 | –28.2 | –21.2 | –16.1 | 9.3 |

| TS1-b2-WW | 86.2 | –4.0 | –2.8 | –5.3 | 24.5 |

| IM-b2-WW | 92.0 | –28.2 | –21.1 | –16.0 | 9.6 |

| TS2-b2-WW | 88.5 | –16.0 | –12.5 | –11.3 | 15.6 |

| CP-b2-WW | 90.7 | –35.6 | –29.9 | –25.3 | –1.4 |

| Pro-b + 3H2O | 83.5 | –12.1 | –13.6 | –14.8 | –16.0 |

| CR-c1-WW | 92.0 | –28.2 | –21.1 | –16.0 | 9.6 |

| TS-c1-WW | 88.4 | –19.4 | –16.1 | –14.7 | 11.8 |

| CP-c1-WW | 91.4 | –50.5 | –44.1 | –39.0 | –14.6 |

| CR-c2-WW | 91.9 | –28.2 | –21.3 | –16.3 | 9.2 |

| TS-c2-WW | 89.3 | –23.2 | –18.9 | –17.0 | 11.0 |

| CP-c2-WW | 91.6 | –51.2 | –44.6 | –39.5 | –14.3 |

| Pro-c + 3H2O | 84.3 | –22.0 | –22.7 | –23.1 | –24.3 |

All units are kcal mol–1.

ZPE, the H and G corrections are calculated at the BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory. The electronic energy values are obtained at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ//BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory.

Figure 4.

Schematic PES for the CH3CH2OH + •OH + 2H2O reaction through path (a1-WW), path (b1-WW), and path (c2-WW), calculated at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ//BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory.

Figure 5.

Geometries of the stationary points in the CH3CH2OH + •OH + 2H2O reaction through path (a1-WW), path (b1-WW), and path (c2-WW) optimized at the BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory. Bond distances are given in Å.

The addition of the third species to CH3CH2OH···H2O···H2O or to •OH···H2O···H2O complexes leads to eight-membered cyclic prereactive complexes, CR-a1-WW and CR-b1-WW with −21.3 and −21.1 kcal mol–1 binding energies, respectively. As evidenced in Figure 5, •OH is located between two water molecules in CR-a1-WW, while it directly forms hydrogen bonds with the hydroxylic hydrogen on ethanol and the oxygen atom of one of the water molecules in CR-b1-WW. The initial CH3CH2OH···H2O···H2O and •OH···H2O···H2O ternary complexes are stable enough that their configurations are hardly affected when they interact with the third species. Starting from the CR-a1-WW complex, the •OH radical extracts one of the β-hydrogen on ethanol in the TS-a1-WW transition state, which has a two-cyclic structure. After crossing the 5.1 kcal mol–1 energy barrier, the CH2CH2OH residue and three water molecules rearrange in the CP-a1-WW product state in such a way that the single ring structure is restored. The formation energy of CP-a1-WW is −37.4 kcal mol–1. Though the water dimer seems to stabilize the intermediate species in path (a1-WW), the small 0.7 kcal mol–1 difference between the energy barrier in this path and that of the corresponding unhydrated path suggests that the effect of the water dimer on β-hydrogen abstraction by •OH is not significant. For the hydroxylic hydrogen abstraction by OH through path (b1-WW), the orientation of •OH in CR-b1-WW is beneficial for abstracting the hydroxylic hydrogen of ethanol. The energy barrier to this abstraction was determined to be 8.6 kcal mol–1. This value is 1.9 kcal mol–1 higher than that in path (b) and only 0.5 kcal mol–1 higher than that in path (b-W), indicating that the negative effect of water on hydroxylic hydrogen abstraction is mainly caused by one water molecule.

For the formation of CH3CHOH through path (c2-WW), the prereactive complex CR-c2-WW is formed through •OH···H2O···H2O + CH3CH2OH and H2O···CH3CH2OH + •OH···H2O interactions. CR-c2-WW is structurally similar to CR-a1-WW, but it only needs to surmount a 2.4 kcal mol–1 energy barrier to form the postreactive complex CP-c2-WW, which quickly dissociates into CH3CHOH + 3H2O. Compared to the corresponding unhydrated path (c), the energy barrier is lower by 1.0 kcal mol–1, revealing a slight catalytic effect of two water molecules on the formation of CH3CHOH.

The interaction of H2O···CH3CH2OH with •OH···H2O gives rise to an additional path for CH3CH2O formation (Figure S2). In this path, the prereactive complex CR-b2-WW, which has an eight-membered structure, is formed 21.2 kcal mol–1 below the reactants. A multiple hydrogen transfer then occurs among •OH, two water molecules, and ethanol in the TS1-b2-WW transition state to form the intermediate complex IM-b2-WW, which is energetically and structurally similar to CR-b1-WW in path (b1-WW). TS1-b2-WW is formed with a very high energy, 18.4 kcal mol–1, and this path is likely negligible. This is similar to the observations in previous hydrogen abstraction reactions involving a multihydrogen transfer mechanism where water molecules actually serve as a bridge.24,33,43

Following the reaction mechanisms discussed above, it is clear that the presence of (H2O)n (n = 1–2) favors the formation of CH3CHOH, while lowering that of CH3CH2O and CH2CH2OH. In a previous research study that studied the water vapor effect on the atmospheric oxidation of CH3OOH by the •OH radical using the CCSD(T)/CBS//BH&HLYP/6-311+G(2df,2p) method, it was found that water played different effects on the formation of different products.25 However, it is not strict to infer the possible effect of the water molecule on the CH3CH2OH + •OH reaction based on the changes in energy barrier exclusively because the concentrations of the initially formed hydrated complexes are usually too small to be relevant in the atmosphere.46−51 For example, it has been reported that the relative abundance of the CH3OH···H2O complex at 50% RH was lower than 0.02%.52 It is then necessary to assess the reaction kinetics to better illustrate the water effect on reaction of ethanol with the hydroxyl radical at tropospheric temperatures.

2.4. Reaction Kinetics

Making use of the energies obtained at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ//BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory (Table 1), the calculated rate coefficients for the bared reaction using eq 18 over the temperature range of 216.7–425.0 K are listed in Table 4. It shows that at 216.7 K, the rate coefficient, kc, for the formation of CH3CHOH through path (c), is about 3 orders of magnitude higher than ka (rate coefficient for the formation of CH2CH2OH) and 4 orders of magnitude higher than kb (rate coefficient for the formation of CH3CH2O). However, as the temperature increases, this advantage is reduced to ∼2 orders of magnitude due to the fast increase of ka and kb, especially ka. The CH2CH2OH branching ratio ra (ra = ka/ktotal, where ktotal is the sum of ka, kb, kc) rises from 0.12% at 216.7 K to 0.57% at 298.2 K and reaches 1.89% at 425.00 K. In a previous study, the channel-specific rate coefficients expressions ka = 1.03 × 10–20T2.68 exp(290 K/T) and kb = 4.67 × 10–22T2.97 exp(292 K/T) cm3 molecule–1 s–1 were derived.16 Our calculated rate coefficients ka and kb in the temperature range of 216.7–298.2 K fit the values calculated from these expressions, if small deviations caused by different theoretical methods are neglected. However, the kc values computed in the present study are higher than previously published values from the following equation: kc = 2.17 × 10–19T2.43 exp(733 K/T) cm3 molecule–1 s–1.16 At room temperature 298.2 K, kc = 9.0 × 10–11 cm3 molecule–1 s–1 in our calculation, higher than 2.6 × 10–12 cm3 molecule–1 s–1 calculated according to the kc expression above. There is a consensus that eq 1c should be the predominant process in the •OH + CH3CH2OH reaction, with eqs 1a and 1b increasing in importance as the temperature increases.14,16,31 Ethanol is considered as a precursor for acetaldehyde through its CH3CHOH and CH3CH2O oxidation products. The high product branching ratio of eq 1c suggests that acetaldehyde might be generated from CH3CHOH predominately over the studied temperature range.

Table 4. Rate Coefficients (cm3 molecule–1 s–1) and Branching Ratios (%) for the Bared CH3CH2OH + •OH Reaction over the Temperature Range of 216.7–425.0 Ka.

| T (K) | ka | kb | kc | ktotal | ka/ktotal | kb/ktotal | kc/ktotal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 216.7 | 3.2 × 10–13 | 2.8 × 10–14 | 2.6 × 10–10 | 2.6 × 10–10 | 0.125 | 0.011 | 99.864 |

| 223.3 | 3.3 × 10–13 | 3.2 × 10–14 | 2.3 × 10–10 | 2.3 × 10–10 | 0.147 | 0.014 | 99.839 |

| 236.3 | 3.7 × 10–13 | 3.9 × 10–14 | 1.9 × 10–10 | 1.9 × 10–10 | 0.198 | 0.021 | 99.781 |

| 249.3 | 4.0 × 10–13 | 4.8 × 10–14 | 1.5 × 10–10 | 1.5 × 10–10 | 0.259 | 0.031 | 99.711 |

| 262.2 | 4.3 × 10–13 | 5.7 × 10–14 | 1.3 × 10–10 | 1.3 × 10–10 | 0.329 | 0.043 | 99.628 |

| 275.2 | 4.6 × 10–13 | 6.7 × 10–14 | 1.1 × 10–10 | 1.1 × 10–10 | 0.408 | 0.059 | 99.533 |

| 288.2 | 4.9 × 10–13 | 7.8 × 10–14 | 9.9 × 10–11 | 9.9 × 10–11 | 0.497 | 0.078 | 99.425 |

| 298.2 | 5.2 × 10–13 | 8.6 × 10–14 | 9.0 × 10–11 | 9.1 × 10–11 | 0.572 | 0.095 | 99.333 |

| 325.0 | 5.8 × 10–13 | 1.1 × 10–13 | 7.3 × 10–11 | 7.3 × 10–11 | 0.798 | 0.153 | 99.049 |

| 425.0 | 8.3 × 10–13 | 2.3 × 10–13 | 4.3 × 10–11 | 4.4 × 10–11 | 1.889 | 0.527 | 97.583 |

ka, kb, and kc are the rate coefficients of path (a), path (b), and path (c), respectively, in the bared reaction, ktotal is the sum of ka, kb, and kc at a given temperature.

The monohydrated reaction proceeds through formation of bimolecular complexes between water and CH3CH2OH or •OH. Upon formation, each of these complexes reacts with the third species to form the prereactive complex. The equilibrium coefficients for the formation of the hydrated complex at different temperatures are given in Table 5. For the formation of •OH···H2O, the equilibrium coefficient (Keq1) is 3.7 × 10–21 cm3 molecule–1. Considering the hydroxyl radical concentration of 2.7 × 107 molecules cm–3 and the water concentration of 7.8 × 1017 molecules cm–3 at 298.2 K, the atmospheric concentration of the •OH···H2O complex is predicted to be 7.7 × 104 molecule cm–3, which is in good agreement with estimates reported in previous works.29,53 Assuming a tropospheric ethanol concentration of 8.1 × 107 molecule cm–3 (30 ppt), which is reasonable in a polluted environment, the concentration of H2O···CH3CH2OH is estimated to be 5.0 × 104 molecule cm–3 at 298.2 K. Noting that at tropospheric temperatures, only less than 0.01% of pure ethanol is in the hydrated form, solely, the rate coefficients (kC1a1-W, kC1b-W, kC1c1-W) for the paths [path (a1-W), (b-W), and (c1-W), respectively] that begin with •OH···H2O at the entrance channel are included in the following discussion. The kinetics results of the other two channels can be found in Tables S2 and S3 in the Supporting Information.

Table 5. Equilibrium Coefficients (cm3 molecule–1) for the Formation of •OH···H2O, CH3CH2OH···H2O, and H2O···CH3CH2OH Complexes (Keq1, Keq2, and Keq3, Respectively) and the Concentration Ratio (r•OH···H2O, rEtOH···H2O, rH2O···EtOH in %, EtOH Stands for CH3CH2OH) of the Hydrated Complexes Relative to the Free Hydroxyl Radical or Ethanola,b.

| T (K) | [H2O] | Keq1 | Keq2 | Keq3 | r•OH···H2O | rEtOH···H2O | rH2O···EtOH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 216.7 | 1.0 × 1015 | 4.7 × 10–20 | 3.8 × 10–21 | 1.1 × 10–20 | 4.7 × 10–3 | 3.8 × 10–4 | 1.1 × 10–3 |

| 223.3 | 2.1 × 1015 | 3.5 × 10–20 | 3.0 × 10–21 | 8.3 × 10–21 | 7.6 × 10–3 | 6.5 × 10–4 | 1.8 × 10–3 |

| 236.3 | 8.1 × 1015 | 2.1 × 10–20 | 2.0 × 10–21 | 5.0 × 10–21 | 1.7 × 10–2 | 1.7 × 10–3 | 4.0 × 10–3 |

| 249.3 | 2.6 × 1016 | 1.4 × 10–20 | 1.4 × 10–21 | 3.1 × 10–21 | 3.6 × 10–2 | 3.7 × 10–3 | 8.2 × 10–3 |

| 262.2 | 7.4 × 1016 | 9.2 × 10–21 | 1.0 × 10–21 | 2.1 × 10–21 | 6.8 × 10–2 | 7.7 × 10–3 | 1.5 × 10–2 |

| 275.2 | 1.9 × 1017 | 6.4 × 10–21 | 7.8 × 10–22 | 1.4 × 10–21 | 1.2 × 10–1 | 1.5 × 10–2 | 2.7 × 10–2 |

| 288.2 | 4.3 × 1017 | 4.6 × 10–21 | 6.0 × 10–22 | 1.0 × 10–21 | 2.0 × 10–1 | 2.6 × 10–2 | 4.4 × 10–2 |

| 298.2 | 7.8 × 1017 | 3.7 × 10–21 | 5.0 × 10–22 | 8.0 × 10–22 | 2.9 × 10–1 | 3.9 × 10–2 | 6.2 × 10–2 |

| 325.0 | 3.0 × 1018 | 9.9 × 10–21 | 3.2 × 10–21 | 2.4 × 10–22 | 6.5 × 10–1 | 1.0 × 10–1 | 1.4 × 10–1 |

| 425.0 | 8.5 × 1019 | 5.4 × 10–22 | 1.1 × 10–22 | 1.1 × 10–22 | 4.6 | 9.6 × 10–1 | 9.3 × 10–1 |

The concentrations (molecule cm–3) of H2O are calculated at 100% RH.

rOH···H2O = [•OH···H2O]/[•OH] = Keq1[•OH][H2O]/[•OH] = Keq1[H2O], rCH3CH2OH···H2O = [CH3CH2OH···H2O]/[CH3CH2OH] = Keq2[CH3CH2OH][H2O]/[CH3CH2OH] = Keq2[H2O], rH2O···CH3CH2OH = [H2O···CH3CH2OH]/[CH3CH2OH] = Keq3[H2O][CH3CH2OH]/[CH3CH2OH] = Keq3[H2O].

For the reaction involving two water molecules, the equilibrium coefficients of the CH3CH2OH···H2O···H2O complex (Keq4) are larger than those of the •OH···H2O···H2O complex (Keq5) (Table S4), and its subsequent reactions are energetically more favorable. Hence, the kinetic calculation results of the reaction initiated by the CH3CH2OH···H2O···H2O complex are listed in Table S5. The rate coefficients for the reaction through path (a1-WW), (b1-WW), and (c1-WW) are denoted as kC4a1-WW, kC4b-WW, and kC4c2-WW, respectively. The total rate coefficient kC4-WW is the sum of kC4a1-WW, kC4b-WW, and kC4c2-WW.

The total rate coefficients for the reaction of CH3CH2OH with •OH in all cases have a negative temperature dependence due to the rate coefficients of the predominant path (c1-W), that decrease with increasing temperature. At 298.2 K and 100% RH, our calculated total rate coefficient for the monohydrated reaction is 3.6 × 10–11 cm3 molecule–1 s–1, about 1 order of magnitude higher than the experimental value (∼7 × 10–12 cm3 molecule–1 s–1) obtained at 100% RH and 294 K (Table 6).30 For the formation of CH3CHOH, only a small catalytic effect of one water molecule can be observed under 249.3 K. The rate coefficient kc increases faster than kC1c1-W as the temperature increases. The ratio of kc/kC1c1-W surpasses 1.0 above 249.3 K and rises up to 11.9 at 425.0 K, indicating that the effect of one water molecule is inversed when the temperature exceeds 249.3 K. A similar situation has also been observed in earlier studies that focused on the impact of water on the •OH + HOCl reaction.43 Compared to the bared reaction, the presence of one water molecule has a slightly negative effect on the formation of CH2CH2OH and CH3CH2O. The value of ka/kC1a1-W reaches 4.3, whereas kb/kC1b1-W reaches 4.5 at 298.2 K. These ratios are computed to be larger than 10 at higher temperatures. Besides, the presence of one water molecule reduces the products’ branching ratio of CH2CH2OH and CH3CH2O at 298.2 K (by 0.23 and 0.04%, respectively), while increasing that of CH3CHOH by 0.27% at the same temperature.

Table 6. Rate Coefficients (cm3 molecule–1 s–1) and Branching Ratios (%) of the Monohydrated CH3CH2OH + •OH Reaction via Channel 1 over the Temperature Range of 216.7–425.0 Ka.

| T (K) | kC1a1-W | kC1b-W | kC1c1-W | kC1-W | kC1a1-W/kC1-W | kC1b-W/kC1-W | kC1c1-W/kC1-W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 216.7 | 3.4 × 10–13 | 1.7 × 10–14 | 7.3 × 10–10 | 7.4 × 10–10 | 0.046 | 0.002 | 99.952 |

| 223.3 | 3.0 × 10–13 | 1.7 × 10–14 | 5.3 × 10–10 | 5.3 × 10–10 | 0.057 | 0.003 | 99.940 |

| 236.3 | 2.5 × 10–13 | 1.7 × 10–14 | 2.9 × 10–10 | 2.9 × 10–10 | 0.085 | 0.006 | 99.910 |

| 249.3 | 2.1 × 10–13 | 1.8 × 10–14 | 1.7 × 10–10 | 1.7 × 10–10 | 0.120 | 0.010 | 99.870 |

| 262.2 | 1.8 × 10–13 | 1.8 × 10–14 | 1.1 × 10–10 | 1.1 × 10–10 | 0.165 | 0.017 | 99.819 |

| 275.2 | 1.5 × 10–13 | 1.8 × 10–14 | 6.9 × 10–11 | 7.0 × 10–11 | 0.219 | 0.026 | 99.755 |

| 288.2 | 1.3 × 10–13 | 1.9 × 10–14 | 4.7 × 10–11 | 4.7 × 10–11 | 0.284 | 0.039 | 99.677 |

| 298.2 | 1.2 × 10–13 | 1.9 × 10–14 | 3.6 × 10–11 | 3.6 × 10–11 | 0.342 | 0.052 | 99.606 |

| 325.0 | 1.0 × 10–13 | 1.9 × 10–14 | 1.9 × 10–11 | 1.9 × 10–11 | 0.530 | 0.103 | 99.367 |

| 425.0 | 6.1 × 10–14 | 2.2 × 10–14 | 3.6 × 10–12 | 3.7 × 10–12 | 1.653 | 0.604 | 97.742 |

kC1a1-W, kC1b-W, and kC1c1-W are the rate coefficients of path (a1-W), path (b-W), and path (c1-W), respectively, via channel 1 in the water-assisted reaction; kC1-W is the sum of kC1a1-W, kC1b-W, and kC1c1-W at temperature T.

Contrary to the inhibitive effect of one water molecule, the rate coefficients, kC4a1-WW, for the formation of CH2CH2OH, are 2–3 orders of magnitude higher than those of the bared reaction over the studied temperature range. kC4b1-WW and kC4c1-WW are also observed to increase by about 1 order of magnitude within the same temperature range. Compared to the water-free case at 298.2 K, the branching ratio of CH2CH2OH (kC4a1-WW/kC4-WW, 2.39%) in the presence of two water molecules increases by 4 times while that of CH3CHOH (kC4c1-WW/kC4-WW) reduces by 1.79%. This suggests that the role of ethanol as the precursor of formaldehyde and peroxyl radicals, which can be produced through further oxidation of CH2CH2OH, may be enhanced in the atmosphere by the presence of two water molecules.

To practically and comprehensively illustrate the effect of (H2O)n (n = 1–2) on the studied reaction, the effective rate coefficients (k′) that take into account the concentration of water need to be evaluated. The rates for the reactions in the absence of water and in the presence of one and two water molecules are given by the following equations, respectively

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

where kC1-W′ and kC4-WW are the effective rate coefficients in the presence of one and two water molecules, respectively, and are given as

| 11 |

| 12 |

Here, the concentrations of the water molecule and water dimer at 298.2 K and 100% RH are calculated to be 7.8 × 1017 and 3.5 × 1014 molecules cm–3, respectively.24 Based on the different hydrogen abstraction sites on ethanol, the corresponding effective rate coefficients are listed in Tables 7 and S6. Additionally, to clearly reveal the effect of (H2O)n (n = 1–2) on the investigated reaction, direct comparison between effective rate coefficients for reactions involving (H2O)n (n = 1–2) and rate coefficients for the bared reaction is shown in Table 8. The results show that the reactions beginning with •OH···H2O + CH3CH2OH at the entrance channel are 3 to 5 orders of magnitude slower than the reactions in the absence of water, indicating that water effectively hinders the reactions between ethanol and the hydroxyl radical. For the hydrogen abstraction from the hydroxyl and methylene groups in the CH3CH2OH···H2O···H2O + •OH channel, the values of the effective rate coefficients are 7–8 orders of magnitude lower than those of the bared reaction. An obvious suppressive effect of two water molecules on methylic hydrogen abstraction is also predicted with effective rate coefficients 6–7 orders of magnitude lower than the rate coefficients of the unhydrated reactions. From this perspective, it is concluded that the presence of (H2O)n (n = 1–2) actually slows down the CH3CH2OH + •OH reaction over the temperature range of 216.7–425.0 K.

Table 7. Effective Rate Coefficients (cm3 molecule–1 s–1) of Monohydrated CH3CH2OH + •OH Reaction over the Temperature Range of 216.7–425.0 Ka.

| T (K) | kC1a1-W′ | kC1b-W′ | kC1c1-W′ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 216.7 | 1.6 × 10–17 | 8.1 × 10–19 | 3.5 × 10–14 |

| 223.3 | 2.3 × 10–17 | 1.3 × 10–18 | 4.0 × 10–14 |

| 236.3 | 4.3 × 10–17 | 3.0 × 10–18 | 5.0 × 10–14 |

| 249.3 | 7.4 × 10–17 | 6.3 × 10–18 | 6.1 × 10–14 |

| 262.2 | 1.2 × 10–16 | 1.2 × 10–17 | 7.3 × 10–14 |

| 275.2 | 1.8 × 10–16 | 2.2 × 10–17 | 8.4 × 10–14 |

| 288.2 | 2.7 × 10–16 | 3.7 × 10–17 | 9.4 × 10–14 |

| 298.2 | 3.5 × 10–16 | 5.4 × 10–17 | 1.0 × 10–13 |

| 325.0 | 6.5 × 10–16 | 1.3 × 10–16 | 1.2 × 10–13 |

| 425.0 | 2.8 × 10–15 | 1.0 × 10–15 | 1.6 × 10–13 |

kC3a1-W, kC3b-W, and kC3c1-W are the rate coefficients of path (a1-W), path (b-W), and path (c1-W), respectively, via channel 3 in the water-assisted reaction, and kC3-W is the sum of kC3a1-W, kC3b-W, and kC3c1-W at temperature T.

Table 8. Ratios of Effective Rate Coefficients of Hydrated Reactions to the Corresponding Rate Coefficients of the Bared CH3CH2OH + •OH Reactions over the Temperature Range of 216.7–425.0 K.

| T (K) | kC1a1-W′/ka | kC4a1-WW′/ka | kC1b-W′/kb | kC4b-WW′/kb | kC1c1-W′/kc | kC4c1-WW′/kc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 216.7 | 4.9 × 10–5 | 1.8 × 10–6 | 2.9 × 10–5 | 6.1 × 10–8 | 1.3 × 10–4 | 8.3 × 10–8 |

| 223.3 | 6.8 × 10–5 | 1.9 × 10–6 | 4.1 × 10–5 | 7.7 × 10–8 | 1.7 × 10–4 | 1.0 × 10–7 |

| 236.3 | 1.2 × 10–4 | 2.0 × 10–6 | 7.7 × 10–5 | 1.1 × 10–7 | 2.7 × 10–4 | 1.5 × 10–7 |

| 249.3 | 1.8 × 10–4 | 2.0 × 10–6 | 1.3 × 10–4 | 1.6 × 10–7 | 4.0 × 10–4 | 2.1 × 10–7 |

| 262.2 | 2.8 × 10–4 | 2.0 × 10–6 | 2.1 × 10–4 | 2.0 × 10–7 | 5.5 × 10–4 | 2.6 × 10–7 |

| 275.2 | 4.0 × 10–4 | 2.0 × 10–6 | 3.3 × 10–4 | 2.5 × 10–7 | 7.4 × 10–4 | 3.2 × 10–7 |

| 288.2 | 5.4 × 10–4 | 1.9 × 10–6 | 4.8 × 10–4 | 3.0 × 10–7 | 9.6 × 10–4 | 3.8 × 10–7 |

| 298.2 | 6.8 × 10–4 | 1.8 × 10–6 | 6.2 × 10–4 | 3.3 × 10–7 | 1.1 × 10–3 | 4.2 × 10–7 |

| 325.0 | 1.1 × 10–3 | 1.5 × 10–6 | 1.1 × 10–3 | 4.1 × 10–7 | 1.7 × 10–3 | 5.2 × 10–7 |

| 425.0 | 3.4 × 10–3 | 7.0 × 10–7 | 4.4 × 10–3 | 4.8 × 10–7 | 3.8 × 10–3 | 5.9 × 10–7 |

3. Conclusions

The gas-phase reaction of ethanol and hydroxyl radical is of great atmospheric importance due to the formation of secondary pollutants, formaldehyde, and peroxyl radicals through further oxidation of C2H5O isomers. In this work, we investigated the effect of water [(H2O)n (n = 1–2)] on the title reaction over the temperature range of 216.7–425.0 K, from the perspective of both energy profiles and kinetics using theoretical calculations. Our results show that although the inclusion of water aids in building ring-like configurations that stabilize prereactive complexes, transition states, and postreactive complexes, the products are not changed. In all cases, the hydrogen abstraction from the methylene group of ethanol by •OH to form CH3CHOH is predominantly preferred over the formation of CH2CH2OH and CH3CH2O by methylic hydrogen abstraction and hydroxylic hydrogen abstraction, respectively. However, water has different effects on the energy barrier of three hydrogen extraction reactions. The energy barrier for the formation of CH3CHOH is decreased by 1.4 and 1.0 kcal mol–1 in the mono- and dihydrated reaction, respectively, whereas for the formation of CH3CH2O, the barrier height is increased by 1.4 and 1.9 kcal mol–1, respectively. However, there is no obvious effect of water on the energy barrier for the formation of CH2CH2OH.

The temperature-dependent rate coefficient of bared reaction and effective rate coefficient of hydrated reaction were investigated using the harmonic transition-state theory over the temperature range of 216.7–425.0 K. The rate coefficients for the formation of CH2CH2OH, CH3CH2O, and CH3CHOH at 298.2 K are calculated to be 5.2 × 10–13, 8.6 × 10–14, and 9.0 × 10–11 cm3 molecule–1 s–1, respectively. By considering •OH···H2O + CH3CH2OH as the main entrance channel in monohydrated reaction, our results show that depending on the hydrogen position on ethanol, the presence of a single water molecule slows down the hydrogen abstraction by 3–5 orders of magnitude. The branching ratios of CH2CH2OH, CH3CH2O, and CH3CHOH are almost insensitive to the presence of one water molecule. For the reaction involving the water dimer, which mainly proceeds through the CH3CH2OH···H2O···H2O + •OH channel, the effective rate coefficients are 6–8 orders of magnitude lower than the rate coefficients of corresponding water-free reactions. The water dimer is estimated to reduce the CH3CHOH branching ratio by ∼2% over the temperature range of 216.7–298.2 K, whereas the branching ratio of CH2CH2OH has risen by around 2%. Overall, the estimated energetic and kinetic characterization of (H2O)n (n = 1–2) in the title reaction would facilitate the understanding of the fate of ethanol and the secondary pollutants derived from it. The current results are also important for further understanding of atmospheric models to predict the concentration of relevant atmospheric pollutants.

4. Computational Method

All the quantum chemical calculations have been carried out with the Gaussian 09 program package.54 The optimization and characterization of all stationary points on PES were performed using the Becke-half-and-half-Lee–Yang–Parr (BH&HLYP) hybrid density functional with the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set.55,56 For the purpose of delineating the nature (minima or saddle points) of the stationary points on the PES, providing ZPE and thermal correction to enthalpy and Gibbs free energy, we also calculated the harmonic vibrational frequencies at the same level of theory. Scaling factors were not used on harmonic vibrational frequencies because they are usually derived for specific systems and may lead to erroneous results when applied to other systems.57 The effect of anharmonicity on di- and higher hydrates is notable and would result in improved thermochemistry of the systems at hand.58,59 Unfortunately, the determination of accurate force fields is sufficiently difficult by the spectral method or theoretical method and the construction of reliable scaling factors has been shown to be difficult even for small systems.58,60 Besides, given the high computational cost of anharmonic vibrational frequency calculations, anharmonicity was not considered in this study. The spin contamination often arises from unrestricted density functional theory (DFT) calculations, and it is not guaranteed that the electronic states from these calculations are eigenstates of the Ŝ2 operator. For our calculations, it was found to be negligible for all electronic states, ranging between 0.003 and 0.018.

Moreover, we carried out intrinsic reaction coordinate calculations to guarantee that the transition-state structures with only one imaginary frequency obtained from frequency calculations perfectly connected the reactants to the desired products.61,62 The BH&HLYP functional has been widely applied to illustrate hydrogen abstraction mechanisms in molecule–radical reactions, and the theoretically predicted rate coefficients and branching ratios exhibited reasonable agreement with experiments.25,40,63 Because the treatment of electron correlation is critical to obtaining more compatible reaction energy, coupled to the high sensitivity of the kinetic calculations to the activation energy, the final energies were obtained by performing more accurate CCSD(T) single-point energy calculations on the BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ method-optimized structures.64

The temperature-dependent rate coefficients and branching ratios both in the absence and in the presence of water were calculated using the energies obtained at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ//BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory based on harmonic transition-state theory.65,66 Taking the bared reaction as the model reaction to determine the kinetics, the following two elementary steps have been considered

| 13 |

| 14 |

A similar procedure is valid for the reaction in the presence of water. The first step is the reversible and barrierless formation of a prereactive complex (CR) that is assumed to be in equilibrium with the reactants. k1 and k–1 denotes the collision rate coefficient of reactants and evaporation rate coefficient of CR, respectively. The second step is the irreversible hydrogen abstraction of ethanol by the hydroxyl radical, where k2 represents the rate coefficient of the reaction from CR to the corresponding products. Using harmonic transition-state theory, the temperature-dependent reaction rate coefficient k2 can be calculated as

| 15 |

where vTS are the harmonic frequencies (the imaginary frequency is omitted) for the transition state and vreact are the harmonic frequencies for CR, Ea is the energy separating the prereactive complex and transition state, R is molar gas coefficient, and T is the absolute temperature.

According to the approximation that the prereactive complexes are on pseudo-steady state conditions, the overall reaction rate coefficient k can be expressed as67

| 16 |

Noting that the entropy change in k–1 for transforming the prereactive complex into the original reactants is fairly larger than that in k2 for the formation of products,68,69 one can expect that k–1 is much larger than k2, so that k–1 + k2 ≈ k–1. The equilibrium coefficient (keq) for the formation of the prereactive complex is expressed as

| 17 |

where ρ0 is the standard density and ΔG is Gibbs free energy change when forming the prereactive complex from the reactants. Equation 16 can then be rewritten as

| 18 |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (91644214, 21707080), Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (2017M612276), Shandong Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (JQ201705), Shandong Key R&D Program (2018GSF117040), Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University (2017JQ01) and International Postdoctoral Exchange Fellowship Program. We acknowledge the High-Performance Computing Center of Shandong University and National Supercomputing Center in Shenzhen for providing the computational resources.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.9b00145.

DFT energetics and frequencies of species on PES; rate coefficients and branching ratios for water-assisted CH3CH2OH + •OH reaction through channel 2, channel 3, and channel 4; equilibrium coefficients for the formation of CH3CH2OH···H2O···H2O, •OH···H2O···H2O complexes and the concentration ratio of hydrated complexes relative to the free hydroxyl radical or ethanol; effective rate coefficients of the dihydrated CH3CH2OH + •OH reaction; schematic PES and geometries of the stationary points for the reaction through path (a2-W), path (c2-W), path (a2-WW), path (b2-WW), and path (c1-WW) calculated at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc pVTZ//BH&HLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kirstine W. V.; Galbally I. E. The Global Atmospheric Budget of Ethanol Revisited. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 545–555. 10.5194/acp-12-545-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naik V.; Fiore A. M.; Horowitz L. W.; Singh H. B.; Wiedinmyer C.; Guenther A.; de Gouw J. A.; Millet D. B.; Goldan P. D.; Kuster W. C.; Goldstein A. Observational Constraints on the Global Atmospheric Budget of Ethanol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 5361–5370. 10.5194/acp-10-5361-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karl T.; Curtis A. J.; Rosenstiel T. N.; Monson R. K.; Fall R. Transient Releases of Acetaldehyde from Tree leaves - Products of a Pyruvate Overflow Mechanism?. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 1121–1131. 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00889.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Millet D. B.; Apel E.; Henze D. K.; Hill J.; Marshall J. D.; Singh H. B.; Tessum C. W. Natural and Anthropogenic Ethanol Sources in North America and Potential Atmospheric Impacts of Ethanol Fuel Use. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 8484–8492. 10.1021/es300162u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammann M.; Cox R. A.; Crowley J. N.; Jenkin M. E.; Mellouki A.; Rossi M. J.; Troe J.; Wallington T. J. Evaluated Kinetic and Photochemical Data for Atmospheric Chemistry: Volume VI - Heterogeneous Reactions with Liquid Substrates. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 8045–8228. 10.5194/acp-13-8045-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr S. A.; Blitz M. A.; Seakins P. W. Site-Specific Rate Coefficients for Reaction of OH with Ethanol from 298 to 900 K. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 3335–3345. 10.1021/jp200186t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders S. M.; Jenkin M. E.; Derwent R. G.; Pilling M. J. Protocol for the Development of the Master Chemical Mechanism, MCM v3 (Part A): Tropospheric Degradation of Non-Aromatic Volatile Organic Compounds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2003, 3, 161–180. 10.5194/acp-3-161-2003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson R. Atmospheric Chemistry of VOCs and NOx. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 2063–2101. 10.1016/s1352-2310(99)00460-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson R.; Baulch D. L.; Cox R. A.; Crowley J. N.; Hampson R. F.; Hynes R. G.; Jenkin M. E.; Rossi M. J.; Troe J.; IUPAC Subcommittee I. Evaluated kinetic and photochemical data for atmospheric chemistry: Volume II – gas phase reactions of organic species. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2006, 6, 3625–4055. 10.5194/acp-6-3625-2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson M. Z. Effects of Ethanol (E85) versus Gasoline Vehicles on Cancer and Mortality in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 4150–4157. 10.1021/es062085v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez E.; Gilles M. K.; Ravishankara A. R. Kinetics of the Reactions of the Hydroxyl Radical with CH3OH and C2H5OH Between 235 and 360 K. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2003, 157, 237–245. 10.1016/s1010-6030(03)00073-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon T. J.; Hölscher D.; Sivakumaran V.; Horowitz A.; Crowley J. N. Kinetics of the Reactions of HO with Methanol (210-351 K) and with Ethanol (216-368 K). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 349–355. 10.1039/b413961e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramakrishnan R.; Su M.-C.; Michael J. V.; Klippenstein S. J.; Harding L. B.; Ruscic B. Rate Constants for the Thermal Decomposition of Ethanol and Its Bimolecular Reactions with OH and D: Reflected Shock Tube and Theoretical Studies. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 9425–9439. 10.1021/jp104759d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galano A.; Alvarez-Idaboy J. R.; Bravo-Pérez G.; Ruiz-Santoyo M. E. Gas phase Reactions of C1-C4 Alcohols with the OH Radical: A Quantum Mechanical Approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002, 4, 4648–4662. 10.1039/b205630e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Truhlar D. G. Multi-path variational transition state theory for chemical reaction rates of complex polyatomic species: ethanol + OH reactions. Faraday Discuss. 2012, 157, 59–88. 10.1039/c2fd20012k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S.; Lin M. C. Theoretical Study on the Kinetics for OH Reactions with CH3OH and C2H5OH. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2007, 31, 159–166. 10.1016/j.proci.2006.07.132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marinov N. M. A detailed chemical kinetic model for high temperature ethanol oxidation. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 1999, 31, 183–220. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vöhringer-Martinez E.; Tellbach E.; Liessmann M.; Abel B. Role of water complexes in the reaction of propionaldehyde with OH radicals. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 9720–9724. 10.1021/jp101804j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloveichik P.; O’Donnell B. A.; Lester M. I.; Francisco J. S.; McCoy A. B. Infrared Spectrum and Stability of the H2O-HO Complex: Experiment and Theory. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 1529–1538. 10.1021/jp907885d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du S.; Francisco J. S.; Kais S. Study of Electronic Structure and Dynamics of Interacting Free Radicals Influenced by Water. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 124312. 10.1063/1.3100549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.; Kupiainen-Maatta O.; Zhang H. J.; Li H.; Zhong J.; Kurten T.; Vehkamaki H.; Zhang S. W.; Zhang Y. H.; Ge M.; Zhang X. H.; Li Z. S. Clustering Mechanism of Oxocarboxylic Acids Involving Hydration Reaction: Implications for the Atmospheric Models. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 148, 214303. 10.1063/1.5030665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer Z. C.; Takahashi K.; Skodje R. T. Water Catalysis and Anticatalysis in Photochemical Reactions: Observation of a Delayed Threshold Effect in the Reaction Quantum Yield. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 15154–15157. 10.1021/ja107335t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buszek R. J.; Torrent-Sucarrat M.; Anglada J. M.; Francisco J. S. Effects of a Single Water Molecule on the OH+H2O2 Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 5821–5829. 10.1021/jp2077825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du B.; Zhang W. The Effect of (H2O)(n) (n=1-2) or H2S on the Hydrogen Abstraction Reaction of H2S by OH Radicals in the Atmosphere. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2015, 1069, 77–85. 10.1016/j.comptc.2015.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anglada J. M.; Crehuet R.; Martins-Costa M.; Francisco J. S.; Ruiz-López M. The Atmospheric Oxidation of CH3OOH by the OH Radical: The Effect of Water Vapor. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 12331–12342. 10.1039/c7cp01976a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S.; Tsona N. T.; Li J.; Du L. Role of Water on the H-Abstraction from Methanol by ClO. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 71, 89–98. 10.1016/j.jes.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Tsona N. T.; Du L. Effect of a Single Water Molecule on the HO2 + ClO Reaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 10650–10659. 10.1039/c7cp05008a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Tsona N. T.; Du L. The Role of (H2O)(1-2) in the CH2O + ClO Gas-Phase Reaction. Molecules 2018, 23, 2240. 10.3390/molecules23092240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglada J. M.; Gonzalez J. Different Catalytic Effects of a Single Water Molecule: The Gas-Phase Reaction of Formic Acid with Hydroxyl Radical in Water Vapor. ChemPhysChem 2009, 10, 3034–3045. 10.1002/cphc.200900387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jara-Toro R. A.; Hernández F. J.; Garavagno M. d. L. A.; Taccone R. A.; Pino G. A. Water Catalysis of the Reaction Between Hydroxyl Radicals and Linear Saturated Alcohols (Ethanol and n-Propanol) at 294 K. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 27885–27896. 10.1039/c8cp05411h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeilsticker K.; Lotter A.; Peters C.; Bosch H. Atmospheric Detection of Water Dimers via Near-Infrared Absorption. Science 2003, 300, 2078–2080. 10.1126/science.1082282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn M. E.; Pokon E. K.; Shields G. C. Thermodynamics of Forming Water Clusters at Various Temperatures and Pressures by Gaussian-2, Gaussian-3, Complete Basis Set-QB3, and Complete Basis Set-APNO Model Chemistries; Implications for Atmospheric Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 2647–2653. 10.1021/ja038928p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T.; Lan X.; Qiao Z.; Wang R.; Yu X.; Xu Q.; Wang Z.; Jin L.; Wang Z. Role of the (H2O)(n) (n=1-3) Cluster in the HO2 + HO → 3O2 + H2O Reaction: Mechanistic and Kinetic Studies. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 8152–8165. 10.1039/c8cp00020d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R.; Kang J.; Zhang S.; Shao X.; Jin L.; Zhang T.; Wang Z. Catalytic Effect of (H2O)(n) (n=1-2) on the Hydrogen Abstraction Reaction of H2O2 + HS → H2S + HO2 under Tropospheric Conditions. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2017, 1110, 25–34. 10.1016/j.comptc.2017.03.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du B.; Zhang W. Catalytic Effect of Water, Water Dimer, or Formic Acid on the Tautomerization of Nitroguanidine. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2014, 1049, 90–96. 10.1016/j.comptc.2014.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schrems O.; Oberhoffer H. M.; Luck W. A. P. Hydrogen bonding in low-temperature matrixes: 1. Proton donor abilities of fluoro alcohols. Comparative infrared studies of ROH.cntdot..cntdot..cntdot.O(CH3)2 complex formation in the gas phase, in carbon tetrachloride solution, and in solid argon. J. Phys. Chem. 1984, 88, 4335–4342. 10.1021/j150663a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Zhong J.; Vehkamäki H.; Kurtén T.; Wang W.; Ge M.; Zhang S.; Li Z.; Zhang X.; Francisco J. S.; Zeng X. C. Self-Catalytic Reaction of SO3 and NH3 to Produce Sulfamic Acid and Its Implication to Atmospheric Particle Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 11020–11028. 10.1021/jacs.8b04928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscic B.; Boggs J. E.; Burcat A.; Császár A. G.; Demaison J.; Janoschek R.; Martin J. M. L.; Morton M. L.; Rossi M. J.; Stanton J. F.; Szalay P. G.; Westmoreland P. R.; Zabel F.; Bérces T. IUPAC Critical Evaluation of Thermochemical Properties of Selected Radicals. Part I. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2005, 34, 573–656. 10.1063/1.1724828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meier U.; Grotheer H. H.; Riekert G.; Just T. Temperature-Dependence and Branching Ratio of the C2H5OH+OH Reaction. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1985, 115, 221–225. 10.1016/0009-2614(85)80684-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elm J.; Bilde M.; Mikkelsen K. V. Influence of Nucleation Precursors on the Reaction Kinetics of Methanol with the OH Radical. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 6695–6701. 10.1021/jp4051269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper P. D.; Kjaergaard H. G.; Langford V. S.; McKinley A. J.; Quickenden T. I.; Schofield D. P. Infrared Measurements and Calculations on H2O·HO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6048–6049. 10.1021/ja034388k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur R.; Vikas V. Exploring the role of a single water molecule in the tropospheric reaction of glycolaldehyde with an OH radical: a mechanistic and kinetics study. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 29080–29098. 10.1039/c6ra01299j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J.; Anglada J. M.; Buszek R. J.; Francisco J. S. Impact of Water on the OH + HOCl Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 3345–3353. 10.1021/ja100976b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno N.; Tonokura K.; Tezaki A.; Koshi M. Water Dependence of the HO2 self reaction: Kinetics of the HO2-H2O Complex. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 3153–3158. 10.1021/jp044592+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T.; Wang R.; Wang W.; Min S.; Xu Q.; Wang Z.; Zhao C.; Wang Z. Water Effect on the Formation of 3O2 from the Self-Reaction of two HO2 Radicals in Tropospheric Conditions. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2014, 1045, 135–144. 10.1016/j.comptc.2014.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buszek R. J.; Barker J. R.; Francisco J. S. Water Effect on the OH + HCl Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 4712–4719. 10.1021/jp3025107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J.; Anglada J. M. Gas Phase Reaction of Nitric Acid with Hydroxyl Radical without and with Water. A Theoretical Investigation. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 9151–9162. 10.1021/jp102935d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuga C.; Alvarez-Idaboy J. R.; Vivier-Bunge A. On the Possible Catalytic Role of a Single Water Molecule in the Acetone + OH Gas Phase Reaction: A Theoretical Pseudo-Second-Order Kinetics Study. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2011, 129, 209–217. 10.1007/s00214-011-0921-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iuga C.; Alvarez-Idaboy J. R.; Vivier-Bunge A. Single water-molecule catalysis in the glyoxal+OH reaction under tropospheric conditions: Fact or fiction? A quantum chemistry and pseudo-second order computational kinetic study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010, 501, 11–15. 10.1016/j.cplett.2010.10.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iuga C.; Alvarez-Idaboy J. R.; Reyes L.; Vivier-Bunge A. Can a Single Water Molecule Really Catalyze the Acetaldehyde + OH Reaction in Tropospheric Conditions?. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 3112–3115. 10.1021/jz101218n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaida V.; Headrick J. E. Physicochemical Properties of Hydrated Complexes in the Earth’s Atmosphere. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 5401–5412. 10.1021/jp000115p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen D. L.; Kurtén T.; Jørgensen S.; Wallington T. J.; Baggesen S. B.; Aalling C.; Kjaergaard H. G. On the Possible Catalysis by Single Water Molecules of Gas-Phase Hydrogen Abstraction Reactions by OH Radicals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 12992–12999. 10.1039/c2cp40795g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allodi M. A.; Dunn M. E.; Livada J.; Kirschner K. N.; Shields G. C. Do Hydroxyl Radical-Water Clusters, OH(H2O)(n), n=1-5, Exist in the Atmosphere?. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 13283–13289. 10.1021/jp064468l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Caricato M.; Li X.; Hratchian H. P.; Izmaylov A. F.; Bloino J.; Zheng G.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M. J.; Heyd J.; Brothers E. N.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A. P.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Rega N.; Millam N. J.; Klene M.; Knox J. E.; Cross J. B.; Bakken V.; Adamo C.; Jaramillo J.; Gomperts R.; Stratmann R. E.; Yazyev O.; Austin A. J.; Cammi R.; Pomelli C.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Voth G. A.; Salvador P.; Dannenberg J. J.; Dapprich S.; Daniels A. D.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.. Gaussian 09, Revision E.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2013.

- Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti Correlation-Energy Formula into a Functional of the Electron Density. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elm J.; Jørgensen S.; Bilde M.; Mikkelsen K. V. Ambient Reaction Kinetics of Atmospheric Oxygenated Organics with the OH Radical: A Computational Methodology Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 9636–9645. 10.1039/c3cp50192b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukonen V.; Kurtén T.; Ortega I. K.; Vehkamäki H.; Pádua A. A. H.; Sellegri K.; Kulmala M. Enhancing Effect of Dimethylamine in Sulfuric Acid Nucleation in the Presence of Water - A Computational Study. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 4961–4974. 10.5194/acp-10-4961-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha P.; Boesch S. E.; Gu C.; Wheeler R. A.; Wilson A. K. Harmonic Vibrational Frequencies: Scaling Factors for HF, B3LYP, and MP2 Methods in Combination with Correlation Consistent Basis Sets. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 9213–9217. 10.1021/jp048233q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kathmann S.; Schenter G.; Garrett B. The Critical Role of Anharmonicity in Aqueous Ionic Clusters Relevant to Nucleation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 4977–4983. 10.1021/jp067468u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurten T.; Noppel M.; Vehkamaki H.; Salonen M.; Kulmala M. Quantum Chemical Studies of Hydrate Formation of H2SO4 and HSO4-. Boreal Environ. Res. 2007, 12, 431–453. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C.; Schlegel H. B. An Improved Algorithm for Reaction Path Following. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 2154. 10.1063/1.456010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C.; Schlegel H. B. Reaction Path Following in Mass-Weighted Internal Coordinates. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 5523–5527. 10.1021/j100377a021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen V. F.; Ørnsø K. B.; Jørgensen S.; Nielsen O. J.; Johnson M. S. Atmospheric Chemistry of Ethyl Propionate. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 5164–5179. 10.1021/jp300897t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pople J. A.; Krishnan R.; Schlegel H. B.; Binkley J. S. Electron Correlation Theories and their Application to the Study of Simple Reaction Potential Surfaces. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1978, 14, 545–560. 10.1002/qua.560140503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hänggi P.; Talkner P.; Borkovec M. Reaction-Rate Theory: Fifty Years after Kramers. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1990, 62, 251–341. 10.1103/revmodphys.62.251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bork N.; Kurtén T.; Vehkamäki H. Exploring the Atmospheric Chemistry of O2S3- and Assessing the Maximum Turnover Number of Ion-Catalysed H2SO4 Formation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 3695–3703. 10.5194/acp-13-3695-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton D. L.; Cvetanovic R. J. Temperature Dependence of the Reaction of Oxygen Atoms with Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 6812–6819. 10.1021/ja00438a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du B.; Zhang W. Theoretical Study on the Water-Assisted Reaction of NCO with HCHO. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 6883–6892. 10.1021/jp405687c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Idaboy J. R.; Mora-Diez N.; Vivier-Bunge A. A Quantum Chemical and Classical Transition State Theory Explanation of Negative Activation Energies in OH Addition To Substituted Ethenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 3715–3720. 10.1021/ja993693w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.