Abstract

The object of this work is to prepare quinoxaline-based benzoxazines and evaluate thermal properties of their thermosets. For this object, 4,4′-(quinoxaline-2,3-diyl)diphenol (QDP)/furfurylamine-based benzoxazine (QDP-fu) and 4,4′,4″,4‴-([6,6′-biquinoxaline]-2,2′,3,3′-tetrayl)tetraphenol (BQTP)/furfurylamine-based benzoxazine (BQTP-fu) were prepared. The structures of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu were successfully confirmed by FTIR and 1H and 13C NMR spectra. We studied the curing behavior of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu and thermal properties of their thermosets. According to DSC thermograms, QDP-fu and BQTP-fu have the attractive onset exothermic temperatures of 181 and 186 °C, respectively. The onset temperature is approximately 45 °C lower than that of a bisphenol A/furfurylamine-based benzoxazines. According to DMA TMA and TGA thermograms, the thermoset of BQTP-fu shows impressive thermal properties, with a Tg value of 418 °C, a coefficient of thermal expansion of 39 ppm/°C, a 5% decomposition temperature of 430 °C, and a char yield of 72%.

1. Introduction

Quinoxaline, a complex ring of benzene and pyrazine, is generally formed by the condensation of an ortho-diamine with a dialdehyde,1 ethanol,2 1,4-dioxane-2,3-diol,3 and so on. Polyquinoxalines, prepared by the reaction of a bis(o-diamine) with a bisglyoxal4 or a bisbenzil,5 are a class of high-performance polymers with many attractive properties, including excellent hydrolytic, thermal, and mechanical properties. In addition, quinoxaline derivatives have shown antibacterial, antiviral, herbicidal, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor properties.6−13

Benzoxazine are heterocyclic compounds and will proceed ring-opening polymerization (ROP) during thermal treatment.14−20 Benzoxazine thermosets have unique properties such as moderate-to-high thermal properties and dimensional stability, and low surface free energy.21,22 The properties of benzoxazine thermosets are strongly influenced by the structures of their precursors. Because polyquinoxalines are a class of high-performance polymers, benzoxazines with quinoxaline as a core might result in high performance. However, to the best of our knowledge, the literature on quinoxaline-containing 1,3-benzoxazines is rare and limited to three patents.23−25 Wang et al. prepared benzoxazines from a quinoxaline-containing aminophenol (Scheme 1a),23 aminophenol (Scheme 1b),24 and triamine (Scheme 1c).25 The benzoxazine thermosets show Tg values as high as 195, 213, and 372 °C, respectively. Generally, it is difficult to prepare a benzoxazine monomer from an aminophenol because it is an A–B type reactant, and will lead to oligomeric benzoxazines.26 In addition, it is difficult to prepare a benzoxazine monomer from triamine because the reaction of triamine with formaldehyde led to a triazine network and resulted in gelation.27 To avoid these problems, the authors use a three-step procedure to prepare the desired benzoxazine monomers.28 Although high-purity benzoxazines can be prepared through that approach, multiple steps (at least four) are required to prepare the aforementioned quinoxaline-containing 1,3-benzoxazines.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of a Quinoxaline-Containing Benzoxazine from (a) Aminophenol,23 (b) Aminophenol,24 and (c) Triamine25 by a Three-Step Procedure28.

Furfurylamine is typically formed by the amination of furfural, which is a product of acid-catalyzed dehydration of 5-carbon sugars,29 and is one of the oldest renewable chemicals.30 Furfurylamine-containing benzoxazines received much attention because of their low cost and high performance. For example, Liu et al. prepared a bisphenol A/furfurylamine-based benzoxazine and found that the reaction between furan and oxazine increased the thermal stability.31 Verge et al. prepared benzoxazines from phloretic acid-derived biphenols and furfurylamine.32 The work highlighted the suitability of phloretic acid to act as a green and efficient alternative to phenol. Endo et al. prepared guaiacol/furfurylamine-based benzoxazine, they reported that the furan moiety participates in the ROP of benzoxazines via electrophilic aromatic substitution.33 Varma et al. prepared a vanillin/furfurylamine-based benzoxazine.34 A curing mechanism of furan electrophilic substitution and decarboxylation was proposed. Dumas et al. prepared resorcinol/furfurylamine-based and hydroquinone/furfurylamine-based benzoxazines by a solventless method. The thermosets exhibit excellent thermomechanical properties with glass transition temperatures higher than 280 °C and present remarkable inherent charring ability upon pyrolysis.35 Dumas et al. also prepared a water-soluble arbutin/furfurylamine-based benzoxazine in a solventless method. Thermoset with a Tg of 190 °C and good adhesion on various substrates was achieved.36 Liu et al. prepared a daidzein/furfulylamine-based bio-benzoxazine through a microwave-assisted synthesis in PEG 400.37 According to the literature, a thermoset with a Tg of 391 °C dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA data), the highest Tg value that has ever reported at that time, was achieved.

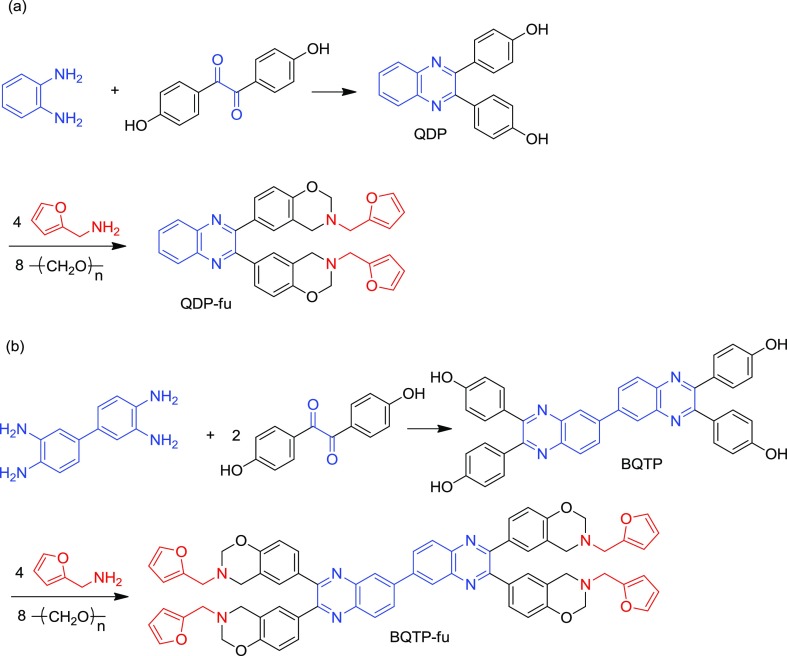

In this work, we report the facile synthesis two quinoxaline-containing benzoxazines. The first one is a difunctional benzoxazine (QDP-fu), prepared from the Mannich condensation of furfurylamine, formaldehyde, and 4,4′-(quinoxaline-2,3-diyl)diphenol (QDP). The second one is a tetrafunctional benzoxazine (BQTP-fu) from the Mannich condensation of furfurylamine, formaldehyde, and 4,4′,4″,4‴-([6,6′-biquinoxaline]-2,2′,3,3′-tetrayl)tetraphenol (BQTP). We studied the curing behavior of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu and thermal properties of their thermosets. Detailed synthesis and characterization of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu and the properties of their thermosets were analyzed in this work.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of QDP and BQTP

The biphenol (QDP) was prepared from the condensation of 4,4-dihydroxybenzil with o-phenylenediamine. The tetraphenol (BQTP) was prepared from the condensation of 4,4-dihydroxybenzil with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Scheme 2). Figure 1 shows the 1H–13C HETCOR NMR spectra of (a) QDP and (b) BQTP. The correlation in Figure 1 supports the structure of QDP and BQTP.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of (a) QDP and QDP-fu (b) BQTP and BQTP-fu.

Figure 1.

Enlarged 1H–13C HETCOR NMR spectrum of (a) QDP and (b) BQTP.

Synthesis and Characterization of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu

According to the literature,38 benzoxazine synthesis is proceeded by two steps: the formation of triazine and the dissociation of the resulting triazine. In our previous work,39 we found that the solvents influence the reaction rate of the two steps, and the co-solvent of toluene/ethanol works best for the synthesis of benzoxazine. QDP-fu was synthesized from the Mannich condensation of furfurylamine, formaldehyde, and QDP (Scheme 2). Table 1 (Runs 1–6) lists the effect of reaction conditions on the preparation of QDP-fu. Reacting in 1,4-dioxane (Run 1), a common solvent for Mannich condensation, at 80 °C for 12 h led to low conversion and low yield. Reacting in dioxane/ethanol at 85–95 °C (Runs 2–4) and toluene/ethanol at 80 °C (Runs 5), a recommended medium for Mannich condensation in our previous work,39 also led to an incomplete reaction with low yield. We think that the conjugation of phenol with quinoxaline reduced the reactivity (Scheme 3). Therefore, a solvent with a higher boiling point was considered. Xylene was chosen to replace toluene, and 1-pentanol was chosen to replace ethanol. Reacting in xylene/1-pentanol at 120 °C (Run 6), as expected, led to a complete reaction and an 85% yield. BQTP-fu can also be successfully synthesized in xylene/pentanol at 120 °C from the Mannich condensation of furfurylamine, formaldehyde, and BQTP (Scheme 2). Because of the resonance of phenol and C=N of quinoxaline that will reduce the electron density of the phenol group in QDP and BQTP, the preparation of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu is not as easy as a bisphenol A/furfurylamine-based benzoxazine. Therefore, the high-boiling co-solvent of xylene/1-pentanol that can provide high reaction temperature at 120 °C, works the best.

Table 1. Reaction Conditions on the Synthesis of QDP-fu.

| run | solvent | reaction conditions (temp, concentration) | result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | dioxane | 85 °C, 0.1 g/mL | incomplete reaction (yield <25%) |

| 2 | dioxane/ethanol (1:1) | 85 °C, 0.1 g/mL | incomplete reaction (yield <25%) |

| 3 | dioxane/1-propanol (1:2) | 95 °C, 0.1 g/mL | incomplete reaction (yield <25%) |

| 4 | dioxane/1-propanol (2:1) | 95 °C, 0.1 g/mL | incomplete reaction (yield <40%) |

| 5 | toluene/ethanol (2:1) | 80 °C, 0.1 g/mL | incomplete reaction (yield <40%) |

| 6 | xylene/1-pentanol (2:1) | 120 °C, 0.1 g/mL | pure product (yield 85%) |

Scheme 3. Conjugation of Phenol with Quinoxaline.

Figure 2 shows the 1H NMR spectrum of QDP and QDP-fu. For the QDP-fu, no phenolic hydroxyl at 9.8 ppm was observed, indicating the completion of the reaction. The characteristic peaks at 7.6, 6.4, and 6.2 ppm (H15–H17 for furan), 4.89 and 3.87 ppm (H12 and H11 for oxazine) confirm the structure of QDP-fu. Figure 3 shows the 13C NMR spectrum QDP-fu. The characteristic peaks at 152.4, 142.7, 110.4, and 108.7 ppm (C14–C17 for furan), 81.2 and 48.5 ppm (C12 and C11 for oxazine) confirm the structure of QDP-fu. Figure 4 shows the enlarged (a) 1H–1H COSY and (b) 1H–13C HETCOR NMR spectra of QDP-fu. The correlation of NMR signals is consistent with the structure of QDP-fu.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectra of QDP and QDP-fu in DMSO-d6.

Figure 3.

13C NMR spectrum of QDP-fu.

Figure 4.

Enlarged (a) 1H–1H COSY and (b) 1H–13C HETCOR. NMR spectra of QDP-fu in DMSO-d6.

Figure 5 shows the 1H NMR spectrum of BQTP and BQTP-fu. For BQTP-fu, no phenolic hydroxyl at 9.8 ppm was observed, indicating the completion of the reaction. The characteristic peaks at 7.6, 6.4, and 6.2 ppm (H19–H21 for furan), 4.89 and 3.8 ppm (H15 and H16 for oxazine) confirm the structure of BQTP-fu. Figure 6 shows the 13C NMR spectrum of BQTP-fu. The characteristic peaks at 152.4, 142.7, 110.4, and 108.7 ppm (C18–C21 for furan), 82.0 and 48.5 ppm (C16 and C15 for oxazine) confirm the structure. Figure 7 shows the enlarged (a) 1H–1H COSY and (b) 1H–13C HETCOR NMR spectra of BQTP-fu. The assignments of NMR signals are consistent with the structure of BQTP-fu.

Figure 5.

1H NMR spectra of BQTP and BQTP-fu in DMSO-d6.

Figure 6.

13C NMR spectrum of BQTP-fu.

Figure 7.

Enlarged (a) 1H–1H COSY and (b) 1H–13C HETCOR NMR spectra of BQTP-fu in DMSO-d6.

2.2. DSC Thermograms

Figure 8 displays the differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermograms of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu. QDP-fu and BQTP-fu, respectively, show a melting point at 65 and 102 °C, and an onset exothermic temperature approximately at 202 and 204 °C and an enthalpy of 359 and 172 kJ/mol, respectively. The onset exothermic temperature is approximately 25 °C lower than that of bisphenol A/furfurylamine-based benzoxazine (BA-fu).31 We prepared the 4,4′-bisphenol F/furfuylamine-based benzoxazine (BF-fu) for comparison of the DSC thermogram (Figure 8). The onset exothermic temperature is approximately 18 °C higher than that of QDP-fu. We speculate that the lone pair of nitrogen of quinoxaline might plays a role in catalyzing the ring opening of oxazine. It probably explains the lower onset exothermic temperatures of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu than those of BA-fu and BF-fu. However, a detailed analysis is required to confirm for the speculation. The exothermic peaks of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu are different from general benzoxazines. They are not symmetrical and seem to be the combination of two exothermic peaks. The same result was also observed for BF-fu. From IR analysis (Figure 10, to be discussed later), we found sequential curing reactions for QDP-fu and BQTP-fu. The sequential curing reactions probably explain the two exothermic peaks of QDP-fu, BQTP-fu, and BF-fu.

Figure 8.

DSC heating thermograms of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu.

Figure 10.

FTIR spectra of (a) QDP-fu and (b) BQTP-fu during curing process.

2.3. Rheology Curves

Figure 9 shows the isothermal rheology curves of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu at 180 °C. The gelation time was determined by the moduli cross-over point in the isothermal, isochronic curves. QDP-fu has a gelation time of 25.1 min, while BQTP-fu, because of its tetrafunctional characteristic, has a shorter gelation time of 11.1 min.

Figure 9.

Isothermal rheology curves of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu at 180 °C.

2.4. IR Analysis

Referring to the curing chemistry of furan and benzoxazine,33,40 three reaction routes for the curing of QDP-fu are shown in Scheme 4. The first route is the ring opening of benzoxazine, forming an intermediate with zwitterions of oxazine. The second route is the reaction of furan and the zwitterion of oxazine, leading to structure 2. The third route is the reaction of free ortho and zwitterion of oxazine, leading to structure 3. FTIR was used to monitor the curing reactions. Figure 10a shows the IR spectra of QDP-fu after thermal treatment for 20 min at each temperature. As curing progressed, the absorption at 930 cm–1 (C–H out-of-plane bending absorption of oxazine) decreased remarkably. The signal of the trisubstituted benzene ring31,41,42 at 1501 cm–1 decreased gradually with the curing temperature. This result confirms the curing of oxazine during the heating process. The signal of furan40 at 985 cm–1 decreased gradually and disappeared after curing at 200 °C. The decrease of the signals of furan and the trisubstituted benzene ring at the early stages of curing supports the reaction routes 1–2 shown in Scheme 4.The signal of the tetrasubstituted benzene ring31,33,40 at 1477 cm–1, which resulted from structure 3 shown in Scheme 4, increased gradually after curing at 200 °C. Therefore, the IR results indicate that routes 1,2 occurred at a lower temperature (before 180 °C), and route 2 occurred at a higher temperature (after 200 °C). Figure 10b shows the IR spectra of BQTP-fu after thermal treatment for 20 min at each temperature. The analytic result of BQTP-fu is the same as that of QDP-fu. We think that the sequence reactions are responsible for the two exothermic peaks of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu in the DSC thermograms of QDP-fu and BQTP-fu (Figure 8).

Scheme 4. Curing Chemistry for QDP-fu.

2.5. Thermal Properties

Figure 11 shows the thermal mechanical analysis (TMA) thermograms of QDP and BQTP after curing at 220 or 240 °C. The thermosets are named C-QDP-fu-X and C-BQTP-fu-X, in which X is the final curing temperature. The TMA result is listed in Table 2. Curing at 240 °C lead to thermosets with a higher Tg than curing at 220 °C. For example, C-QDP-fu-240 and C-BQTP-fu-240 have a Tg value of 268 and 295 °C, respectively, which are about 30 °C higher than those of C-QDP-fu-220 and C-BQTP-fu-220. Therefore, the final curing temperature of all samples is set to 240 °C, and the sample ID is named C-QDP-fu and C-BQTP-fu (we delete the “–240” for simplicity). TMA data show that thermoset based on tetrafunctional BQTP-fu has a higher Tg value and lower coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) than that based on difunctional QDP-fu. For example, the Tg and CTE value of C-BQTP-fu are 298 °C and 39 ppm/°C, which are better than those of C-QDP-fu (268 °C and 58 ppm/°C), demonstrating the advantage of tetrafunctional characteristic.

Figure 11.

TMA thermograms of C-QDP-fu-X and C-BQTP-fu-X.

Table 2. Thermal Properties of Thermosets of the Benzoxazines.

| sample code | Tg (°C)a (DMA) | Tg (°C)b(TMA) | CTEc(ppm/°C) | E′d (GPa) | Td5e (°C) | Td10f (°C) | char yieldg(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-QDP-fu | 329 | 268 | 58 | 1.3 | 410 | 486 | 72 |

| C-BQTP-fu | 419 | 295 | 39 | 4.0 | 430 | 519 | 72 |

Measured by DMA at a heating rate of 5 °C/min.

Measured by TMA at a heating rate of 5 °C/min.

CTE, recorded from 50 to 150 °C.

Storage modulus (E′) is recorded at 50 °C.

Temperature corresponding to 5% weight loss by thermogravimetry at a heating rate of 20 °C/min.

Temperature corresponding to 10% weight loss by thermogravimetry at a heating rate of 20 °C/min.

Residual wt % at 800 °C.

Figure 12 shows the DMA thermograms of C-QDP-fu and C-BQTP-fu. C-BQTP-fu, derived from tetrafuctional BQTP-fu, shows higher modulus (4.0 GPa) than the C-QDP-fu do (1.3 GPa). The Tg taken from the peak temperatures of tan δ are 329 and 419 °C, respectively. The value of 329 °C is similar to the Tg value of thermoset of difunctional bisphenol A/furfurylamine-based benzoxazine.31 However, the Tg value of 419 °C, to the best of our knowledge, is an ultra-high value for a benzoxazine thermoset. The tetrafunctional characteristic and the furan moiety that increase the cross-linking density explain the very high Tg characteristic.

Figure 12.

DMA thermograms of C-QDP-fu and C-BQTP-fu.

Figure 13 and Table 2 show the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) data of C-QDP-fu and C-BQTP-fu. The 5% decomposition temperatures for C-QDP-fu and C-BQTP-fu are 410 and 430 °C, respectively. C-BQTP-fu shows a slightly higher decomposition temperature than C-QDP-fu, probably because of the higher functionality in the precursor. The char yield is as high as 72% for both C-QDP-fu and C-BQTP-fu. Generally, the thermoset of bisphenol-based benzoxazines such as bisphenol F/aniline-based, and bisphenol A/aniline-based benzoxazine exhibit a 5 wt % decomposition temperature at around 300–350 °C.43,44 The result demonstrates the high thermal stability characteristic of C-QDP-fu and C-BQTP-fu.

Figure 13.

TGA thermogram of C-QDP-fu and C-BQTP-fu.

3. Conclusions

We have successfully prepared a quinoxaline-containing diphenol (QDP) and tetraphenol (BQTP). Based on QDP and BQTP, we have successfully prepared two benzoxazines (QDP-fu and BQTP-fu) from the Mannich condensation of furfurylamine, formaldehyde, with QDP and BQTP, respectively, in a co-solvent of xylene/pentanol (2/1, v/v) at 120 °C. 1H and 13C, 1H–1H, and 1H–13C NMR spectra have successfully confirmed their structures. Through IR analysis, we found that the curing reactions include a sequential curing procedure. The ring opening of oxazine and the reaction of furan with zwitterion of oxazine take place at the early stage of curing, and the reaction of free ortho with zwitterion of oxazine take place later. Thermal analysis shows that the thermosets (C-QDP-fu and C-BQTP-fu) exhibit very high thermal properties. Especially, C-BQTP-fu showed impressive thermal properties, with a Tg value of 418 °C, a CTE of 39 ppm/°C, a 5% decomposition temperature of 430 °C, and a char yield of 72%. To the best of our knowledge, these properties are competitive to other polybenzoxazines.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

4,4′-Dimethoxybenzil (from Alfa), pyridine hydrochloride (from Alfa), o-phenylenediamine (from Alfa), furfurylamine (from Aldrich), paraformaldehyde (from Acros), and 3,3-diamionbenzidine (from Acros) are used as received. N-Methyl pyrrolidone (HPLC grade from Showa) and N,N-dimethyl acetamide (DMAc, HPLC grade from Showa) were purified by distillation under reduced pressure over calcium hydride (from Acros), and stored over molecular sieves. The other solvents are (HPLC grade) and used without further purification.

4.2. Characterization

DMA was measured using a PerkinElmer Pyris Diamond DMA with a sample size of 5.0 cm in length, 1.0 cm in width, and around 25 μm in thickness. The storage modulus E′ and tan δ were determined as the sample was subjected to the temperature scan mode with a rate of 5 °C/min at a frequency of 1 Hz. The test was performed using a tension mode with an amplitude of 25 μm. TMA was performed using an SII TMA/SS6100 with a heating rate of 5 °C/min. The sample size is the same as the DMA measurement. The CTE was recorded at the temperature range of 50–150 °C. TGA was performed with a PerkinElmer Pyris1 at a heating rate of 20 °C/min under an atmosphere of nitrogen or air. DSC scans were obtained using a PerkinElmer DSC 8000 in a nitrogen atmosphere with a heating rate of 10 °C/min. NMR measurements (1H NMR, 13C NMR, 2D COSY (1H–1H) and 2D HETCOR (1H–13C) were performed using a Varian Inova 600 NMR in DMSO-d6. IR spectra were obtained from KBr pallet (concentration 1/100 w/w) at least 32 scans in the standard wavenumber range of 667–4000 cm–1 using a PerkinElmer RX1 infrared spectrophotometer.

4.3. Synthesis of 4,4-Dihydroxybenzil

4,4-Dihydroxybenzil was prepared from demethylation of 4,4′-dimethoxybenzil, according to the literature.45 Light yellow powder with 91% yield was obtained. 1H NMR (ppm, DMSO-d6), δ = 6.90 (4H, H4), 7.73 (4H, H3), 10.81 (2H, OH).

4.4. Synthesis of 4,4′-(Quinoxaline-2,3-diyl)diphenol (QDP)

QDP was prepared according to the following procedure. o-Phenylenediamine 0.67 g (6.2 mmol), 4,4-dihydroxybenzil 1.5 g (6.2 mmol), and toluene/acetic acid (1/2, v/v) 30 mL were introduced into a 100 mL round-bottom glass flask equipped with a condenser and a magnetic stirrer. The solution was stirred at 110 °C for 8 h. The solution was then distilled to remove toluene and poured into water to remove acetic acid. The precipitate was washed by water twice. After drying, yellow powder with a yield of 88% was obtained. 1H NMR (ppm, DMSO-d6): δ = 6.75 (4H, H7), 7.33 (4H, H6), 7.74 (2H, H2), 8.03 (2H, H1), 9.77 (2H, OH). 13C NMR (ppm, DMSO- d6): δ = 114.9 (C7), 128.5 (C1), 129.6 (C4), 129.7 (C2), 131.1 (C6), 140.2 (C3), 152.8 (C5), 158.1 (C8).

4.5. Synthesis of 4,4′,4″,4‴-([6,6′-Biquinoxaline]-2,2′,3,3′-tetrayl)tetraphenol

BQTP was prepared according to the following procedure. 3,3-Diamionbenzidine 0.664 g (3.1 mmol), 4,4-dihydroxybenzil 1.5 g (6.2 mmol), and toluene/acetic acid (1/2, v/v) 30 mL were introduced into a 100 mL round-bottom glass flask equipped with a condenser and a magnetic stirrer. The solution was stirred at 110 °C for 8 h. The solution was then distilled to remove toluene and poured into water to remove acetic acid. The precipitate was washed by water twice. After drying, yellow powder with a yield of 88% was obtained. 1H NMR (ppm, DMSO-d6): δ = 6.75 (8H, H7), 7.34 (8H, H6), 8.07 (2H, H2), 8.22 (2H, H1), 8.42 (2H, H13), 9.79 (4H, OH).·13C NMR (ppm, DMSO-d6): δ = 114.9 (C7), 126.2 (C13), 128.7 (C1), 129.1(C2), 129.6 (C14), 131.2 (C6), 139.6 (C3), 139.9 (C4), 140.4 (C11), 152.9 (C5), 153.3 (C12), and 158.2 (C8).

4.6. Synthesis of QDP/Furfurylamine-Based Benzoxazine (QDP-fu)

QDP 0.695 g (2.21 mmol), paraformaldehyde 0.266 g (8.84 mmol), furfurylamine 0.429 g (4.42 mmol) and xylene/1-pentanol (2/1) 9 mL were introduced into a 100 mL round-bottom glass flask equipped with a condenser and a magnetic stirrer. The mixture was stirred at 130 °C for 24 h. After that, the solution was poured into hexane to precipitate. The precipitate was dissolved in dichloromethane and extracted with 1.0 N NaOH(aq) twice, and water twice. The organic phase was evaporated to afford light yellow powder with a yield of 81%. 1H NMR (ppm, DMSO-d6): δ = 3.84 (4H, H13), 3.87 (4H, H11), 4.89 (4H, H12), 6.27 (2H, H17), 6.41 (2H, H16), 6.73 (2H, H7), 7.19 (2H, H6), 7.21 (2H, H10), 7.60 (2H, H15), 7.78 (2H, H2), 8.05 (2H, H1).·13C NMR (ppm, DMSO-d6): δ = 47.4 (C13), 48.5 (C11), 82.0 (C12), 108.7 (C17), 110.4 (C16), 115.5 (C7), 119.4 (C9), 128.5 (C1), 129.2 (C6), 129.3 (C10), 129.8 (C2), 130.9 (C4), 140.2 (C3), 142.7 (C15), 151.5 (C5), 152.4 (C14), and 154.3 (C8). A melting peak at 65 °C, and an exothermic peak at 235 °C with an enthalpy of 309 J/g (359 kJ/mol) were observed in the DSC thermogram.

4.7. Synthesis of BQTP/Furfurylamine-Based Benzoxazine (BQTP-fu)

BQTP 0.695 g (2.21 mmol), paraformaldehyde 0.266 g (8.84 mmol), furfurylamine 0.43 g (4.42 mmol), and xylene/1-pantanol (2/1) 9 mL were introduced into a 100 mL round-bottom glass flask equipped with a condenser and a magnetic stirrer. The mixture was stirred at 130 °C for 24 h. After that, the solution was poured into hexane to precipitate. The precipitate was dissolved in dichloromethane and extracted with 1.0 N NaOH(aq) twice, and water twice. The organic phase was evaporated to afford yellow powder with a yield of 76%. 1H NMR (ppm, DMSO-d6): δ = 3.82 (16H, H17,15) 4.87 (8H, H16), 6.26 (4H, H21), 6.40 (4H, H20), 6.70 (4H, H7), 7.16 (4H, H6,10), 7.60 (4H, H19), 8.06 (2H, H2), 8.20 (2H, H1), 8.40 (2H, H13). 13C NMR (ppm, DMSO-d6): δ = 47.4 (C17), 48.5 (C15), 82.0 (C16), 108.7 (C21), 110.4 (C20), 115.5 (C7), 119.4 (C9), 126.3 (C13), 128.9 (C6,2,1,10), 130.8 (C14), 139.9 (C4,3,11), 142.7 (C19), 151.5 (C5), 152.4 (C18), 152.8 (C12), and 154.4 (C8). A melting peak at 102 °C, and an exothermic peak at 225 °C with an enthalpy of 223 J/g (172 kJ/mol) were observed in the DSC thermogram.

4.8. Sample Preparation and Curing Procedure

QDP-fu and BQTP-fu were dissolved in DMAc to make a solution with a solid content of 20 wt %. The solution was cast in an aluminum mold, and dried in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h to remove most of the solvent, and then cured at 140, 200, and 240 °C (2 h for each temperature). The thermosetting film is named C-QDP-fu and C-BQTP-fu, in which C represents cured.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the “Advanced Research Center For Green Materials Science and Technology” from The Featured Area Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (107L9006) and the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan (MOST 107-3017-F-002-001 and 107-2221-E-005-026).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Mirjalili B. B. F.; Akbari A. Nano-TiO2: an eco-friendly alternative for the synthesis of quinoxalines. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2011, 22, 753–756. 10.1016/j.cclet.2010.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Climent M. J.; Corma A.; Hernández J. C.; Hungría A. B.; Iborra S.; Martínez-Silvestre S. Biomass into chemicals: one-pot two-and three-step synthesis of quinoxalines from biomass-derived glycols and 1, 2-dinitrobenzene derivatives using supported gold nanoparticles as catalysts. J. Catal. 2012, 292, 118–129. 10.1016/j.jcat.2012.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venuti M. C. 2, 3-Dihydroxy-1, 4-dioxane: a stable synthetic equivalent of anhydrous glyoxal. Synthesis 1982, 1982, 61–63. 10.1055/s-1982-29701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stille J. K.; Williamson J. R. Polyquinoxalines. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Gen. Pap. 1964, 2, 3867–3875. 10.1002/pol.1964.100020904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hergenrother P. M.; Levine H. H. Phenyl-substituted polyquinoxalines. J. Polym. Sci., Part A-1: Polym. Chem. 1967, 5, 1453–1466. 10.1002/pol.1967.150050626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F.; Cheng G.; Hao H.; Wang Y.; Wang X.; Chen D.; Peng D.; Liu Z.; Yuan Z.; Dai M. Mechanisms of Antibacterial Action of Quinoxaline 1, 4-di-N-oxides against Clostridium perfringens and Brachyspira hyodysenteriae. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1948. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughran H. M.; Han Z.; Wrobel J. E.; Decker S. E.; Ruthel G.; Freedman B. D.; Harty R. N.; Reitz A. B. Quinoxaline-based inhibitors of Ebola and Marburg VP40 egress. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2016, 26, 3429–3435. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirado A.; Sánchez J. I. L.; Ruiz-Alcaraz A. J.; Bautista D.; Gálvez J. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 4-alkoxy-6, 9-dichloro [1, 2, 4] triazolo [4, 3-a] quinoxalines as inhibitors of TNF-α and IL-6. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 54, 87–94. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zghaib Z.; Guichou J.-F.; Vappiani J.; Bec N.; Hadj-Kaddour K.; Vincent L.-A.; Paniagua-Gayraud S.; Larroque C.; Moarbess G.; Cuq P.; Kassab I.; Deleuze-Masquéfa C.; Diab-Assaf M.; Bonnet P.-A. New imidazoquinoxaline derivatives: Synthesis, biological evaluation on melanoma, effect on tubulin polymerization and structure–activity relationships. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 2433–2440. 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghattass K.; El-Sitt S.; Zibara K.; Rayes S.; Haddadin M. J.; El-Sabban M.; Gali-Muhtasib H. The quinoxaline di-N-oxide DCQ blocks breast cancer metastasis in vitro and in vivo by targeting the hypoxia inducible factor-1 pathway. Mol. Cancer 2014, 13, 12. 10.1186/1476-4598-13-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deady L. W.; Kaye A. J.; Finlay G. J.; Baguley B. C.; Denny W. A. Synthesis and Antitumor Properties of N-[2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl]carboxamide Derivatives of Fused Tetracyclic Quinolines and Quinoxalines: A New Class of Putative Topoisomerase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40, 2040–2046. 10.1021/jm970044r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noolvi M. N.; Patel H. M.; Bhardwaj V.; Chauhan A. Synthesis and in vitro antitumor activity of substituted quinazoline and quinoxaline derivatives: search for anticancer agent. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 2327–2346. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona P.; Carta A.; Loriga M.; Vitale G.; Paglietti G. Synthesis and in vitro antitumor activity of new quinoxaline derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 1579–1591. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning X.; Ishida H. Phenolic materials via ring-opening polymerization: Synthesis and characterization of bisphenol-A based benzoxazines and their polymers. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 1994, 32, 1121–1129. 10.1002/pola.1994.080320614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H.; Low H. Y. A Study on the Volumetric Expansion of Benzoxazine-Based Phenolic Resin. Macromolecules 1997, 30, 1099–1106. 10.1021/ma960539a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puchot L.; Verge P.; Peralta S.; Habibi Y.; Vancaeyzeele C.; Vidal F. Elaboration of bio-epoxy/benzoxazine interpenetrating polymer networks: a composition-to-morphology mapping. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 472–481. 10.1039/c7py01755c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Ran Q.; Fu Q.; Gu Y. Preparation of Transparent and Flexible Shape Memory Polybenzoxazine Film through Chemical Structure Manipulation and Hydrogen Bonding Control. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 6561–6570. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya G.; Kiskan B.; Yagci Y. Phenolic Naphthoxazines as Curing Promoters for Benzoxazines. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 1688–1695. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b00218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salum M. L.; Iguchi D.; Arza C. R.; Han L.; Ishida H.; Froimowicz P. Making Benzoxazines Greener: Design, Synthesis, and Polymerization of a Biobased Benzoxazine Fulfilling Two Principles of Green Chemistry. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 13096–13106. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b02641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi D.; Ohashi S.; Abarro G. J. E.; Yin X.; Winroth S.; Scott C.; Gleydura M.; Jin L.; Kanagasegar N.; Lo C.; Arza C. R.; Froimowicz P.; Ishida H. Development of Hydrogen-Rich Benzoxazine Resins with Low Polymerization Temperature for Space Radiation Shielding. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 11569–11581. 10.1021/acsomega.8b01297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H.; Agag T.. Handbook of Benzoxazine Resins; Elsevier, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H.; Froimowicz P.. Advanced and Emerging Polybenzoxazine Science and Technology; Elsevier, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.Monoamine - monophenol type quinoxaline phenyl oxazine and its preparation method. China patent no. CN105153194B, 2015.

- Wang J.Monophenols - monoamines type quinoxaline phenyl benzoxazine and preparation method. China patent no. CN105111199B, 2015.

- Wang J., Quinoxaline type triamine benzene and oxazine and its preparation method. China patent no. CN105130975B2015.

- Agag T.; Takeichi T. High-molecular-weight AB-type benzoxazines as new precursors for high-performance thermosets. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2007, 45, 1878–1888. 10.1002/pola.21953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. W.; Lin C. H.; Lin H. T.; Huang H. J.; Hwang K. Y.; Tu A. P. Development of an aromatic triamine-based flame-retardant benzoxazine and its high-performance copolybenzoxazines. Eur. Polym. J. 2009, 45, 680–689. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2008.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. H.; Chang S. L.; Hsieh C. W.; Lee H. H. Aromatic diamine-based benzoxazines and their high performance thermosets. Polymer 2008, 49, 1220–1229. 10.1016/j.polymer.2007.12.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R.; Voorhees V. Furfural. Org. Synth. 1921, 1, 49. 10.15227/orgsyn.001.0049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters F. N. Jr The Furans: Fifteen Years of Progress. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1936, 28, 755–759. 10.1021/ie50319a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.-L.; Chou C.-I. High performance benzoxazine monomers and polymers containing furan groups. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2005, 43, 5267–5282. 10.1002/pola.21023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trejo-Machin A.; Verge P.; Puchot L.; Quintana R. Phloretic acid as an alternative to the phenolation of aliphatic hydroxyls for the elaboration of polybenzoxazine. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 5065–5073. 10.1039/c7gc02348k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Sun J.; Liu X.; Sudo A.; Endo T. Synthesis and copolymerization of fully bio-based benzoxazines from guaiacol, furfurylamine and stearylamine. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 2799–2806. 10.1039/c2gc35796h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sini N. K.; Bijwe J.; Varma I. K. Renewable benzoxazine monomer from Vanillin: Synthesis, characterization, and studies on curing behavior. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2014, 52, 7–11. 10.1002/pola.26981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas L.; Bonnaud L.; Olivier M.; Poorteman M.; Dubois P. High performance bio-based benzoxazine networks from resorcinol and hydroquinone. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 75, 486–494. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2016.01.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas L.; Bonnaud L.; Olivier M.; Poorteman M.; Dubois P. Arbutin-based benzoxazine: en route to an intrinsic water soluble biobased resin. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 4954–4960. 10.1039/c6gc01229a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J.; Teng N.; Peng Y.; Liu Y.; Cao L.; Zhu J.; Liu X. Biobased Benzoxazine Derived from Daidzein and Furfurylamine: Microwave-Assisted Synthesis and Thermal Properties Investigation. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 3175–3183. 10.1002/cssc.201801404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunovska Z.; Liu J. P.; Ishida H. 1,3,5-Triphenylhexahydro-1,3,5-triazine—active intermediate and precursor in the novel synthesis of benzoxazine monomers and oligomers. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 1999, 200, 1745–1752. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. H.; Chang S. L.; Shen T. Y.; Shih Y. S.; Lin H. T.; Wang C. F. Flexible polybenzoxazine thermosets with high glass transition temperatures and low surface free energies. Polym. Chem. 2012, 3, 935–945. 10.1039/c2py00449f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Zhao C.; Sun J.; Huang S.; Liu X.; Endo T. Synthesis and thermal properties of a bio-based polybenzoxazine with curing promoter. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2013, 51, 2016–2023. 10.1002/pola.26587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Yan S. Synthesis and characterization of novel biobased benzoxazines from cardbisphenol and the properties of their polymers. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 61808–61814. 10.1039/c5ra12076d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agag T.; Takeichi T. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Benzoxazine Monomers Containing Allyl Groups and Their High Performance Thermosets. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 6010–6017. 10.1021/ma021775q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ning X.; Ishida H. Phenolic materials via ring-opening polymerization: Synthesis and characterization of bisphenol-A based benzoxazines and their polymers. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 1994, 32, 1121–1129. 10.1002/pola.1994.080320614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Ishida H. Anomalous Isomeric Effect on the Properties of Bisphenol F-based Benzoxazines: Toward the Molecular Design for Higher Performance. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 5682–5690. 10.1021/ma501294y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvid M.; Johansson A.; Bjuggren J. M.; Wutzel H.; Englund V.; Gubanski S.; Müller C.; Andersson M. R. Tailored side-chain architecture of benzil voltage stabilizers for enhanced dielectric strength of cross-linked polyethylene. Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics 2014, 52, 1047–1054. 10.1002/polb.23523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]