Abstract

To improve the adsorption capacity, reduce the disposal cost, and enhance the separation efficiency of common activated carbon as an adsorbent in wastewater treatment, a novel thiol-modified magnetic activated carbon adsorbent of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH was successfully synthesized with a facile and safe hydrothermal method without any toxic and harmful reaction media. The as-prepared NiFe2O4-PAC-SH can effectively remove mercury(II) ions from aqueous solution. The maximal adsorption capacities from the experiment and Langmuir fitting achieve 298.8 and 366.3 mg/g at pH 7, respectively, exceeding most of adsorptive materials. The as-prepared NiFe2O4-PAC-SH has an outstanding regeneration performance, remarkable hydrothermal stability, and efficient separation efficiency. The data of kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics show that the adsorption of mercury(II) ions is spontaneous and exothermic. Ion exchange and electrostatic attraction are the main adsorption factors. The experimental results exhibit that the NiFe2O4-PAC-SH can be a prominent substitute for conventional activated carbon as an adsorbent.

1. Introduction

With the development of industry, various pollutants containing heavy metals, dyes, antibiotics, toxic compounds, etc., are discharged into the water body, resulting in more and more serious water pollution.1 Among these pollutants, the heavy metal mercury has attracted much attention because of its serious damage to the ecosystem and harm to the human body and its characteristics of migration and enrichment. Mercury in wastewater is mainly resulted from chloralkali, plastics, batteries, electronics, and other industries,2,3 which exist in the form of inorganic divalent mercury ions.4,5

To quickly and safely deal with mercury pollution, it is urgent to seek relevant methods or materials to solve these problems. Compared to conventional technologies, including membrane filtration,6 ion exchange,7 biological adsorption,8 chemical precipitation,9 and so on, adsorption method is a low-cost and high-efficiency technology, which can be used to really solve these problems resulted from mercury pollution.10 For example, activated carbon adsorption columns are often employed at the end of the treatment system of electroplating wastewater containing mercury to remove residual heavy metals and ensure the effluent up to the corresponding standards.

Among many adsorbents, activated carbon (AC) is a kind of black porous solid adsorption material with unique properties. During the process of activation of activated carbon, a large amount of interspaces are produced, forming a large surface area and many functional groups, including carboxyl, hydroxyl, and other functional groups.11 The value of the specific surface area (BET) of activated carbon can reach 500–1700 m2/g.

However, although activated carbon is a good adsorbent for removing heavy metals, its adsorption ability is still greatly limited by its nonpolar characteristics, which hinder the interaction between charged metal ions and activated carbon surfaces. Moreover, the other performance of activated carbon, including slow adsorption rate and low adsorption capacity, also severely impairs the application of activated carbon in the wastewater treatment.

Therefore, the chemical modification for activated carbon has received much attention and development. Based on the theory of hard and soft acid–base (HSAB), mercury(II) is a soft acid and easy to form a stable complex with soft alkali, and the reaction process between mercury(II) and soft alkali has a high complexation rate.12−14

Thiol, as a functionalized modified material, has been widely used in the field of materials science. At present, there are more and more researches on the treatment of pollutants with thiol-functionalized adsorbents. Based on the HSAB theory, thiol is a soft alkali and can easily combine with mercury(II) ions to achieve the removal of mercury from the water body.14 There are many thiol-functionalized methods, including silane reaction,15 sulfur modification,16 etc. However, the above methods have some obvious defects, such as complicated operation, very long reaction time, high temperature or high pressure, toxic and harmful reaction media, and so on. Therefore, in order to improve these defects, the grafting of thiol functional groups on the surface of activated carbon was achieved by a simple esterification reaction for only 6 h at 353 K with thioglycolic acid as the modified precursor, concentrated sulfuric acid as the catalyst, and acetic anhydride as the dehydrating agent in the present study. The employed thiol-modified method is simpler, more economical, and safer compared to conventional technologies.

In addition, there is another defect for the application of common powder activated carbon (PAC). Because it is difficult for PAC to be recovered from water after adsorption, which not only restricts its application in water treatment but also increases the disposal cost, the recovery of used PAC from water is of great significance to reduce the disposal cost. In recent years, magnetic technology has been widely developed and employed to solve the above defects of solid–liquid separation in water treatment.17−19 However, some magnetic particles like Fe3O4, CoFe2O4, etc., are easy to be corroded by acidic substances in the wastewater with low pH value.

Hence, the acid-resistant magnetic NiFe2O4 was selected as a magnetic modifier in the present study to enhance the separation efficiency of activated carbon from water after adsorption. Magnetic activated carbon (NiFe2O4-PAC) can be obtained with a co-precipitation method by loading NiFe2O4 on the surface of powdered activated carbon. Finally, the synthesized NiFe2O4-PAC-SH was used to remove mercury(II) ions from wastewater. The adsorption effects of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH on mercury(II) ions, including solution pH, reaction temperature, dosage of adsorbents, and concentration of mercury(II) ions, were all studied. Moreover, the adsorption isotherm model, kinetic model, and thermodynamics were established to explore the adsorption mechanism of mercury(II) ions onto NiFe2O4-PAC-SH. The corresponding possible adsorption mechanism was also proposed based on the experimental results and adsorbent characterization.

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Materials

PAC (charcoal, 200 mesh), NiCl2·6H2O, FeCl3·6H2O, NH3·H2O, sodium hydroxide (NaOH), concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl), and concentrated nitric acid (HNO3) are all purchased from McLean Co., Ltd. (Shanghai). Thioglycolic acid, acetic anhydride, and concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) are obtained from Aladdin Co., Ltd. (Shanghai). All the above reagents are analytical.

2.2. Preparation of NiFe2O4-PAC and NiFe2O4-PAC-SH

A 100 mL HNO3 solution (2 M) containing 10.0 g of PAC was heated to 363 K with continuous stirring for 6 h. After that, the solution was washed to neutral with pure water and then dried in an oven at 333 K. Two grams of PAC was added into a 180 mL mixed solution containing 2.38 g of NiCl2·6H2O and 5.41 g of FeCl3·6H2O. The mixed solution containing PAC was stirred with ultrasonic treatment for 30 min. Afterward, 11 mL of NH3·H2O was added dropwise into the above solution and continued to be stirred for 20 min. Subsequently, the solution was transferred into a 100 mL Teflon autoclave and reacted at 493 K for 12 h. After the reaction, the material of NiFe2O4-PAC was washed several times to neutral and then dried at 333 K.

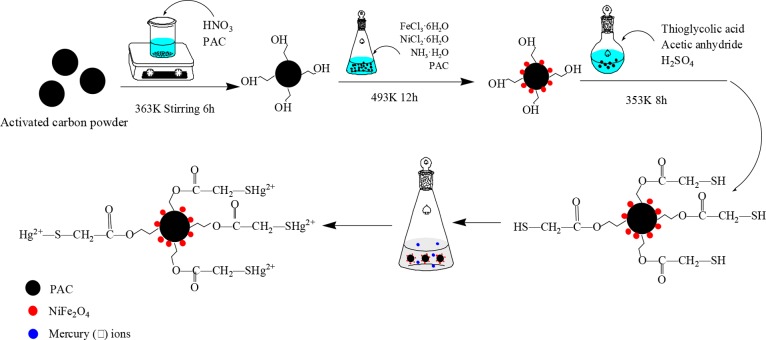

The as-prepared NiFe2O4-PAC (1.0 g) was placed in a brown reagent bottle containing 3.5 mL of thioglycolic acid, 2.5 mL of acetic anhydride, and 25 μL of concentrated H2SO4. The solution was sealed and reacted at 353 K for 8 h. After the reaction, the material was washed with pure water several times and dried at 333 K with vacuum condition. The material of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH was obtained. The scheme of material synthesis and mercury(II) ions removal is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Scheme of material synthesis and mercury(II) ion removal.

2.3. Characterizations

The surface morphology of the as-prepared materials was observed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, ZEISS-SUPRA55, Germany). The crystal structure was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD, D/MAX-2550-18KW, Japan). The functional groups on the surface of the materials were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR, Nicolet-6700, USA) with wavenumbers of 400–4000 cm–1. The magnetic strength of the materials was measured by a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM, Qunantumpesign, MPMS3, USA). The values of the specific surface area (BET) and pore size of the materials were measured by a N2 adsorption–desorption instrument (Autosorb-JQZ-MP-XR-VP, USA). The molecular structure and element types were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Escalab 250, USA). The zeta potentials of the materials were determined by a zeta potentiometer (ZETAPLAS, USA) to analyze the interaction between adsorbents and contaminants in the solution.

2.4. Batch Adsorption Experiments

The adsorption capacities of the adsorbents were evaluated under the conditions of various solution pH, dosage (g), reaction time (t, min), and reaction temperature (T, K). For the effect of solution pH, a 100 mL solution containing mercury(II) ions with initial concentration (C0, 30 mg/L) was added into a 250 mL conical flask and then adjusted to the desired pH values with 0.1 and 1 M HCl or NaOH solution. The equilibrium capacity (qe, mg/g) was determined based on the values of C0, equilibrium concentration (Ce, mg/g), dosage, and solution volume (V, L) through a cold atomic absorption adsorption spectrophotometer (F732-VJ, Jiangfeng, China).20 The experimental conditions were fixed in the dosage of 0.005 g, T = 298 K, and t = 6 h under various pH values of 2–8.

In order to compare the effects of different dosages on the adsorption of mercury(II) ions, the experiment was carried out under the conditions of T = 298 K, t = 6 h, pH 7, V = 100 mL, and C0 = 30.0 mg/L with various dosages of 0.003–0.016 g. For the concentration effect of mercury, the dosages of adsorbents were fixed in 0.005 g with various concentrations of mercury(II) ions of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 5.0, and 8.0 mg/L. The instantaneous capacity (qt, mg/g) was obtained based on the values of C0, instantaneous concentration (Ct, mg/L), dosage, and solution volume at a required time (t, min).21 The removal efficiency (E, %) of mercury(II) ions was calculated based on the values of C0 and Ce.

In the fitting of Langmuir and Freundlich models, 0.005 g of adsorbent was added into the mercury(II) solution with various initial concentrations of C0 = 10.0, 20.0, 30.0, 40.0, and 50.0 mg/L under the temperatures of 298, 308, and 318 K, respectively. The solution pH was adjusted to 7. Adsorption kinetics was carried out under the conditions of a dosage of 0.005 g, C0 = 30.0 mg/L, V = 100 mL, pH 7, T = 298 K, and shaking rate of 165 r/min. The residual concentration of mercury(II) ions was determined at the times of 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 300, 360, and 480 min, respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterizations

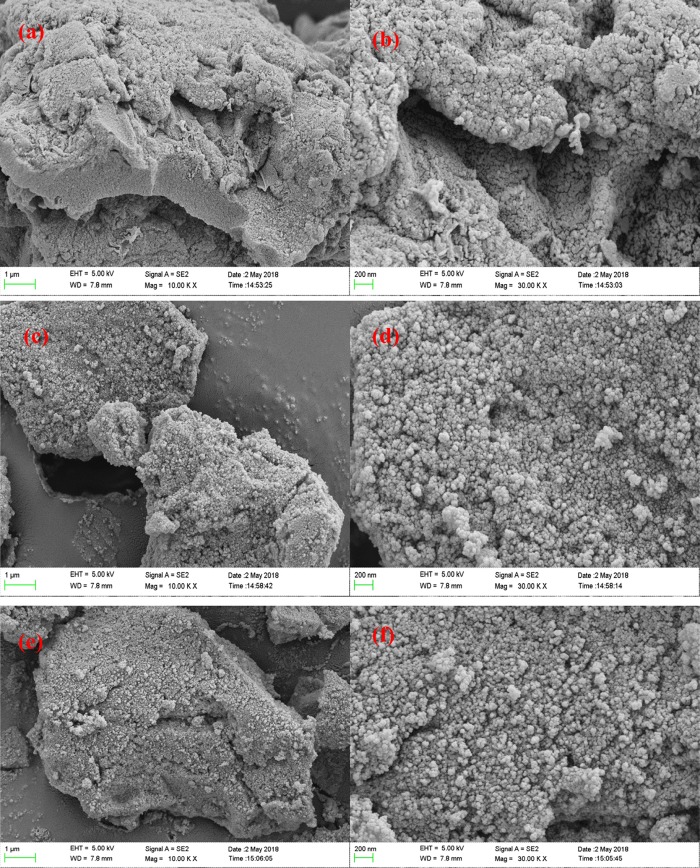

From Figure 2a,b, the surface of activated carbon is relatively smooth, and there are some obvious gaps on the surface of activated carbon. After modification, a large number of NiFe2O4 particles can be found on the surface of activated carbon, as shown in Figure 2c,d, which proves that NiFe2O4 has been successfully loaded on the surface of activated carbon. The size of NiFe2O4 particles is about 20–30 nm.

Figure 2.

SEM images of the as-prepared materials: (a, b) PAC, (c, d) NiFe2O4-PAC, (e, f) NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

Figure 2e,f shows that the amount of NiFe2O4 particles on the surface of activated carbon does not change obviously after grafting the thiol groups through esterification reaction. The result indicates that the as-synthesized NiFe2O4 particles have not been greatly affected during the process of esterification.

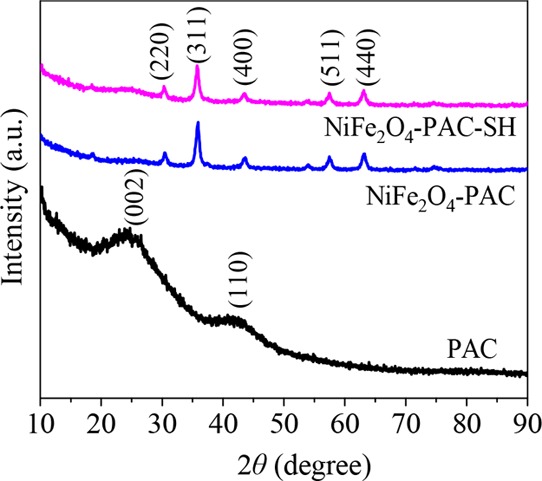

Figure 3 shows the XRD images of PAC, NiFe2O4-PAC, and NiFe2O4-PAC-SH. It can be seen that the as-prepared PAC has two broad and irregular diffraction peaks at the ranges of 20–30° and 40–48°, which corresponds to the (002) and (100) planes,22,23 respectively. The diffraction peaks at 2θ of 30.3°, 35.7°, 43.4°, 57.4°, and 63.0° in the XRD diagrams of NiFe2O4-PAC and NiFe2O4-PAC-SH coincide with the peaks of the (220), (311), (400), (511), and (440) planes in the standard spectrum of NiFe2O4 (JCPDS card no. 54-0964), respectively. From the XRD diagrams of NiFe2O4-PAC and NiFe2O4-PAC-SH, the peak of PAC is not clear. This may be due to the high peak strength of the NiFe2O4 crystal and amorphous structure of PAC, resulting in that the peaks of PAC are not shown.19

Figure 3.

XRD images of PAC, NiFe2O4-PAC, and NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

The XRD result indicates that NiFe2O4 has been successfully synthesized on the surface of activated carbon. Moreover, the main peaks in NiFe2O4-PAC-SH are consistent with those in NiFe2O4-PAC. The fact reveals that the introduction of thiol groups has no effect on the as-synthesized magnetic NiFe2O4 particles. The result can be also proved via the SEM measurement shown in Figure 2.

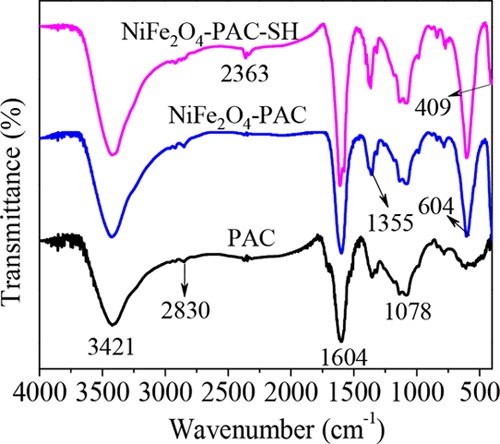

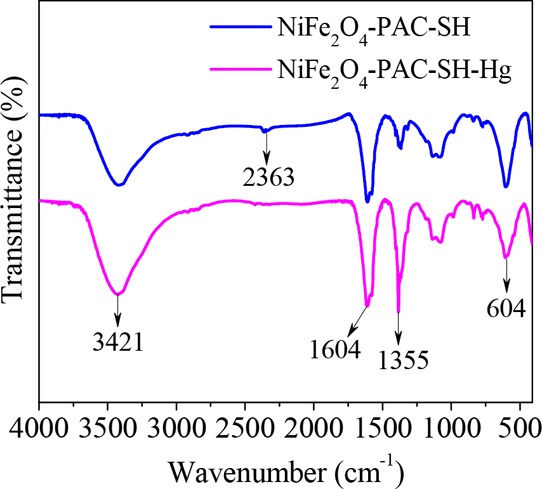

FT-IR technology can be employed to study the performance and change of functional groups on the surface of materials. From Figure 4, two new vibrational peaks at 409 and 604 cm–1 can be observed in the spectra of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH and NiFe2O4-PAC after the loading of NiFe2O4 on the surface of activated carbon, corresponding to the Ni–O and Fe–O vibrational peaks in NiFe2O4 crystals,24,25 respectively. However, the peak of Ni–O is displayed at 409 cm–1 and close to the detection edges of the FT-IR instrument, so this peak of Ni–O is an incomplete absorption peak.

Figure 4.

FT-IR of PAC, NiFe2O4-PAC, and NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

In the FT-IR chromatography, the wide peak at 3421 cm–1 is the stretching vibration peak of −OH.26 The peaks at around 2830 cm–1 are the symmetric stretching peak and antisymmetric stretching peak of −CH2.27 The absorption peak at 1355 cm–1 is the stretching vibration of −CH on the surface of activated carbon.28 The absorption peak at 1078 cm–1 is the stretching vibration of C–O.29 The absorption peak at 1604 cm–1 can be attributed to the stretching vibration of C=O and C–O and the antisymmetric stretching vibration of C=C.30 There is a ring vibration peak at 1604 cm–1 in the chromatography of the three materials, attributed to the stretching vibration of C=O in aromatic esters. The result indicates that the alcohol hydroxyl groups on the surface of activated carbon are successfully esterified with thioglycolic acid. In the FT-IR diagram of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH, there is a weak absorption peak at 2363 cm–1, which is due to the introduction of −SH, but the position of the peak shifts from 2560 cm–1 due to the influence of C≡C.14

Figure S1a,b (Supporting Information) are the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm and pore size distribution of PAC, NiFe2O4-PAC, and NiFe2O4-PAC-SH. From Figure S1a, the adsorption–desorption curve of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH belongs to a type IV isotherm, showing an obvious hysteresis loop. The value of BET, total pore volume, and pore size of the three materials are recorded in Table S1, and the corresponding values of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH are 1700.4 m2/g, 1.59 cm3/g, and 7.45 nm, respectively. Compared with the virgin PAC, the values of BET and pore size changed slightly, but the value of pore volume was greatly increased after modification.

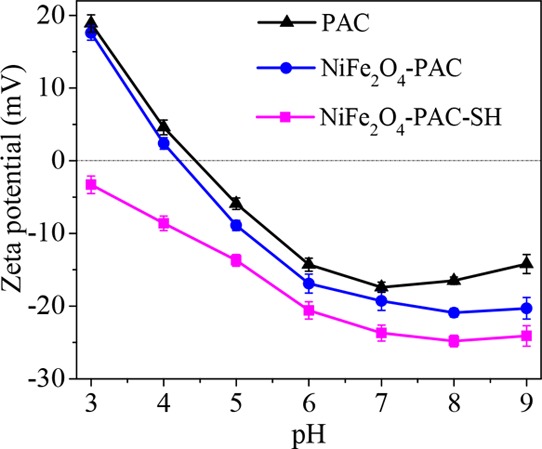

The electrochemical properties of the adsorbent surface play an important role in the adsorption of charged pollutants. Figure 5 shows the zeta potential analysis of the as-prepared three materials. It can be seen that the surface of PAC when pH < 4 presents a negative charge at pH 3–9 and the zeta potential decreases gradually and tends to be gentle with the increase in pH. After grafting of thiol functional groups on the surface of activated carbon, the surface of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH is completely negatively charged at pH 3–9. The potentials of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH are higher than those of PAC and NiFe2O4-PAC at each pH value, which is due to the fact that thiol is a soft base. Moreover, the potential of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH reaches the lowest value of −24.8 mV at pH 8. The increase in surface negative charges is conducive to the adsorption of positively charged mercury(II) ions.

Figure 5.

Zeta potentials of PAC, NiFe2O4-PAC, and NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

Figure 6 shows the magnetic strength of PAC, NiFe2O4-PAC, and NiFe2O4-PAC-SH. The saturation magnetization values of NiFe2O4-PAC and NiFe2O4-PAC-SH are 25.8 and 20.9 emu/g, respectively. It can be seen that the magnetism of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH is a little smaller than that of NiFe2O4-PAC. However, the value does not affect the magnetic separation efficiency of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH. The video in the Supporting Information (Supporting Video 1) reveals a quick separation of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH from aqueous solution after adsorption under an external magnetic field.

Figure 6.

VSM of PAC, NiFe2O4-PAC, and NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

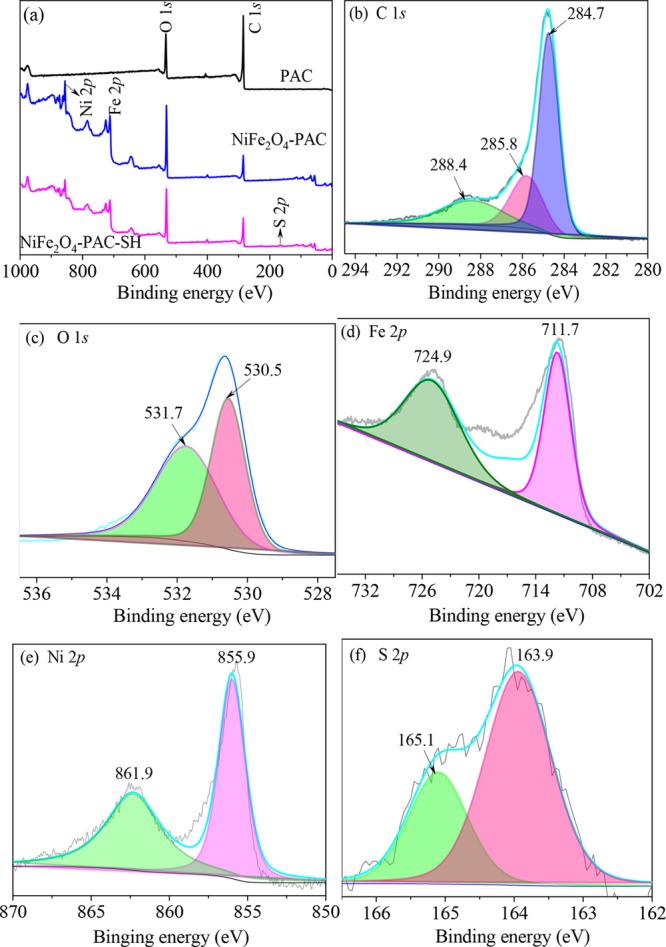

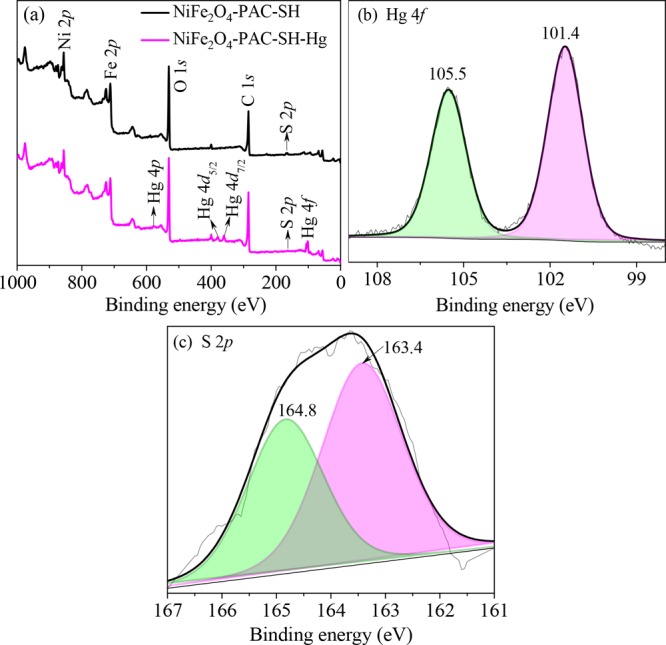

Figure 7a is the XPS spectra before adsorption. From the image, it can be known that the ingredients of PAC are mainly C and O elements. After being modified with magnetic particles, two new peaks of Fe 2p and Ni 2p are easy to be found, which indicates a successful synthesis of NiFe2O4 on the surface of activated carbon. An S 2p peak in the NiFe2O4-PAC-SH can be found, corresponding to the existence of −SH. In Figure 7b, there are three characteristic peaks at 284.7, 285.8, and 288.4 eV, corresponding to the presence of sp2 hybrid carbon in the material, stretching vibrations of C–O, and ester bond O—C=O, respectively.31

Figure 7.

XPS spectra of (a) survey scan, (b) C 1s, (c) O 1s, (d) Fe 2p, (e) N 1s, and (f) S 2p of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

The peaks of O 1s at 530.5 and 531.7 eV shown in Figure 7c are attributed to the inorganic oxygen in NiFe2O432 and characteristic peak of C=O.33 The binding energies of 711.9, 723.3, 855.9, and 861.9 eV in Figure 7d,e are attributed to Fe 2p3/2, Fe 2p1/2, Ni 2p3/2, and Ni 2p1/2,32 respectively. The result demonstrates again the presence of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles in the material. In Figure 7f, the absorbance peaks at 163.9 and 165.1 eV are due to the introduction of −SH after thioglycolic acid was grafted onto the surface of the material,14 corresponding to S 2p1/2 and S 2p3/2, respectively.

3.2. Adsorption Performance

3.2.1. Effect of pH

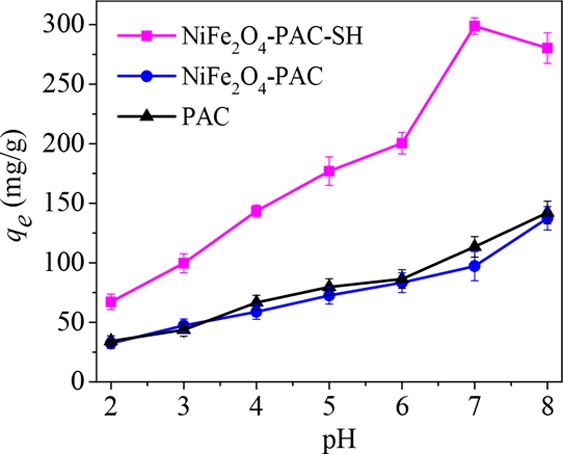

In general, solution pH value has an important influence on the adsorption performance of adsorbents.34 According to the analysis of zeta potential, it can be seen that the pH solution value can affect the surface charges and thus affect the surface activity of the adsorbents. Meanwhile, solution pH also affects the existence morphology of mercury ions. Therefore, it is important to study the effect of various solution pH values on the adsorption of adsorbents for mercury ions.

From Figure 8, it can be seen that the adsorption capacity of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH for mercury(II) ions increases with the increase in pH at the ranges of 2–7. The adsorption capacity reaches a maximum of 298.8 mg/g at pH 7. When the solution pH is greater than 7, the adsorption capacity of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH for mercury(II) ions decreased.

Figure 8.

Effect of pH on the adsorption capacity of the three adsorbents.

It can also be seen from Figure 8 that the adsorption capacity of PAC for mercury(II) ions is similar to that of NiFe2O4-PAC, which indicates that the surface activity of PAC has no obvious enhancement after being modified by NiFe2O4 alone. The result suggests that the key role for adsorption is not the magnetic NiFe2O4 particles. However, after grafting of thiol groups on the surface of activated carbon, the surface activity of PAC obtains significant enhancement, directly resulting in high adsorption capacity and removal efficiency of mercury(II) ions. The result demonstrates that the introduction of −SH has a great promotion on the adsorption capacity of PAC, which is consistent with previous reports.14,21

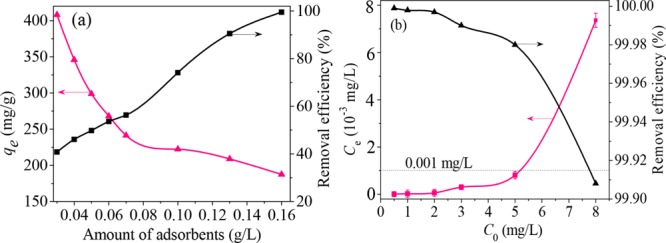

3.2.2. Effect of Dosage and Concentration

The effect of various dosages on the adsorption capacity of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH was investigated, and the results are shown in Figure 9a. It can be seen that the adsorption capacities of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH for mercury(II) ions decrease with the increase in dosage, but the removal efficiencies increase. The reason is that the introduction of −SH groups enhances the surface activity of PAC, leading to high removal efficiencies to mercury(II) ions. However, both the reduction of the number of active sites after continuous adsorption of mercury(II) ions and the neutralization of negative charges on the surface of PAC cause the descending of the adsorption capacity of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH. Moreover, the removal efficiencies are a little low under the very low dosage of adsorbents. However, when the dosage of adsorbents reaches 0.13 g/L, the removal efficiency is up to over 90%. In consideration of economy, the optimum dosage of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH is selected to be 0.05 g/L.

Figure 9.

(a) Effect of dosage and (b) initial concentration with NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

For the removal of mercury(II) in the low polluted water body, assuming that there is 0.005 g of mercury(II) in a liter of water, the concentration of mercury(II) ions is 5 mg/L and belongs to a low-level content. As the maximal adsorption capacity of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH is 298.8 mg/g at pH 7, hence, the residual concentration of mercury(II) ions in treated water should be far below 1 μg/L when the dosage of adsorbents is 0.05 g/L. In order to prove the above speculation, the test of various initial concentrations of mercury(II) was carried out under the conditions of a dosage of 0.05 g/L and solution pH of 7, and the results are shown in Figure 9b. Based on the data in Figure 9b, it can be seen that the residual concentrations Ce of mercury(II) ions are all below 0.001 mg/L, and the removal efficiencies are also over 99.98% when the solution initial concentration C0 is less than or equal to 5 mg/L. The result completely meets the standards of mercury(II) ions (1 μg/L) in natural water defined by the World Health Organization (WHO).35 However, the residual concentrations Ce of mercury(II) ions are over 0.001 mg/L when the initial concentration C0 is greater than 5 mg/L. In fact, the concentration of mercury(II) ions in most of industrial wastewater and common rivers is far below 0.005 g/L. A high concentration of mercury(II) ions in industrial wastewater and rivers usually needs to be treated through a chemical method not an adsorption method. Only when the concentration of mercury(II) ions is below a certain value, the adsorption method is suitable. The above results also show that NiFe2O4-PAC-SH can be used to remove low-concentration mercury in natural water and is a prominent substitute for conventional activated carbon as an adsorbent.

3.3. Adsorption Kinetics

In order to better explore adsorption kinetics of mercury(II) ions, three kinetic models, including pseudo-first-order (eq 1), pseudo-second-order (eq 2), and intraparticle diffusion (eq 3) models, were established to fit the experimental data. The three model fitting formulas are as follows

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where k1 (min–1), k2 (g/mg/min), and kd (mg/g/min0.5) are all constants, and C is the thickness of the boundary layer (mg/g).

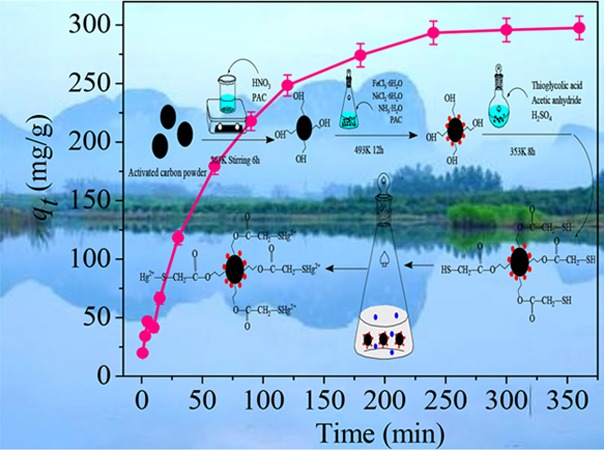

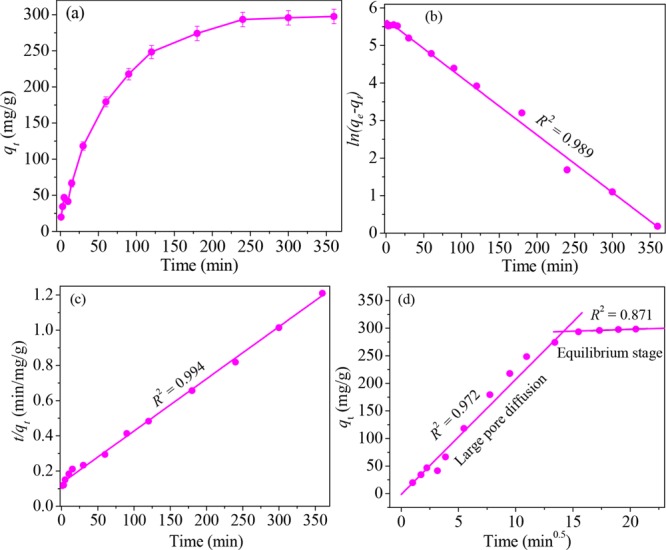

Figure 10a shows the effect of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH on the adsorption to mercury(II) at different times. It can be seen from the diagram that the adsorption of mercury(II) by adsorbents is greatly affected by time. Before 60 min, the adsorption rate of mercury(II) by NiFe2O4-PAC-SH is very fast. The adsorption capacity has reached 179.4 mg /g at 60 min. The reason is due to the relatively large number of active sites on the surface of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH at the beginning of the adsorption reaction. As time goes on, more and more mercury(II) ions are adsorbed onto the adsorbent surface, resulting in a decrease in the concentration gradient between the adsorbent surface and the solution, thus reducing the adsorption rate. When the time reaches 240 min, the adsorption capacity of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH to mercury(II) ions gradually reaches saturation and achieves 298.8 mg/g.

Figure 10.

Effect of time on the (a) adsorption, (b) pseudo-first-order, (c) pseudo-second-order, and (d) intraparticle diffusion models.

To further analyze the fitting results and evaluate the validity of various models, four kinds of error functions, including the coefficient of determination (R2), chi-square test (χ2), sum of square error (SSE), and root mean square error (RMSE), are used. Generally, the higher R2 value or the smaller χ2, SSE, and RMSE values, the better fitting results between the experimental data and the model.14

Figure 10b,c are the fitting results of the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second models, respectively. The corresponding values of R2, χ2, SSE, and RMSE are calculated with the three fitting models, and the results are listed in Table 1. It can be seen that the pseudo-second-order model has higher R2 and smaller χ2, SSE, and RMSE values. Moreover, the theoretical adsorption capacity (qe,cal) in the pseudo-second-order model is 303.4 mg/g, which is close to the experimental capacity (qe,exp, 298.8 mg/g). The result indicates that the pseudo-second-order model has a better consistency with the experimental data compared with the pseudo-first-order model. The adsorption process involves some chemical reaction.36,37 The experimental capacity exceeds many other adsorptive materials as shown in Table 2.

Table 1. Kinetic Parameters for Mercury(II) Adsorption onto NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

| pseudo-first-order model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qe,exp | qe,cal | k1 | R2 | χ2 | SSE | RMSE |

| 298.8 | 337.8 | 0.0153 | 0.989 | 0.146 | 0.206 | 0.126 |

| pseudo-second-order model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qe,exp | qe,cal | k2 | R2 | χ2 | SSE | RMSE |

| 298.8 | 303.4 | 0.0030 | 0.994 | 0.085 | 0.023 | 0.042 |

| intraparticle diffusion model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kd1 | C1 | R12 | kd2 | C2 | R22 |

| 20.85 | –1.33 | 0.972 | 0.761 | 282.79 | 0.871 |

Table 2. Comparison of Adsorption Capacity for Mercury(II) Ions.

| adsorbents | BET (m2/g) | pH | fitting model | Qm (mg/g) | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lignocellulosic | 5 | Freundlich | 20 | (4) | |

| SBA-15-SH | 50.9 | 8 | Freundlich | 195.6 | (14) |

| PEI-AC | 5 | Langmuir | 16.4 | (38) | |

| carbon nanotube | 8 | Langmuir | 100 | (39) | |

| magnetic polypyrrole–GO | 1737.6 | 7 | Langmuir | 400 | (20) |

| thiol-functionalized Fe3O4 | 6 | Langmuir | 344.8 | (40) | |

| thiol-functionalized aluminum oxide hydroxide nanowhiskers | 7 | Langmuir | 114 | (41) | |

| coal-based activated carbon | 900 | 4 | Langmuir | 48.0 | (42) |

| NiFe2O4-PAC-SH | 1241.2 | 7 | Langmuir | 366.3 | this work |

Figure 10d is the fitting result of the intraparticle diffusion model. The fitting plots reveal that there are two stages: large pore diffusion stage and equilibrium adsorption stage. At the first stage, the adsorption process of mercury(II) is transient and fast. A large number of mercury(II) is adsorbed on the outer surface of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH. At the second stage, the concentration gradient of mercury(II) between the surface of adsorbents and the inner solution decreases. As a result, the adsorption rate becomes small and eventually tends to equilibrium.

3.4. Adsorption Isotherms

The adsorption isotherm can not only evaluate the adsorption ability of adsorbents but also describe the interaction between mercury(II) ions and adsorbent surface.43 The as-employed isotherm models are Langmuir (eq 4), Freundlich (eq 5), Temkin (eq 6), and Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R; eq 7) models, which can be described as follows

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

The separation factor (RL) in the Langmuir model can be written as eq 9

| 9 |

where qm (mg/g) is the maximum monolayer adsorption capacity, and KL (L/mg), KF (mg1–nLn/g), and KT are the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin model constants, respectively. 1/n (no unit) is an empirical constant. B = RT/bT (J/mg); ε is the Polanyi potential (J/mol). β is a constant related to the average adsorption energy (E, kJ/mol) and can be calculated using the equation E = (2β)−0.5.

Figure 11 is the fitting results of Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm models. The parameters obtained by fitting the four models are listed in Table 3. It can be seen that the three coefficients of determination R2 of the Langmuir model are higher than those of other three models at three temperatures and the values of χ2, SSE, and RMSE in the Langmuir model is also smaller.

Figure 11.

(a) Langmuir, (b) Freundlich, (c) Temkin, and (d) D–R isotherm curves with NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

Table 3. Isotherm Parameters of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

| Langmuir isotherm | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (K) | Qm | KL | R2 | RL | χ2 | SSE | RMSE |

| 298 | 366.3 | 0.359 | 0.999 | 0.027 | 1.96 × 10–4 | 7.41 × 10–6 | 1.21 × 10–3 |

| 308 | 330.0 | 0.366 | 0.999 | 0.026 | 1.01 × 10–4 | 4.05 × 10–6 | 9.0 × 10–4 |

| 318 | 280.9 | 0.418 | 0.999 | 0.023 | 6.73 × 10–5 | 7.01 × 10–6 | 1.18 × 10–3 |

| Freundlich isotherm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (K) | 1/n | KF | R2 | χ2 | SSE | RMSE |

| 298 | 0.260 | 142.4 | 0.957 | 2.05 × 10–3 | 1.14 × 10–2 | 4.77 × 10–2 |

| 308 | 0.251 | 133.5 | 0.950 | 2.10 × 10–3 | 1.16 × 10–2 | 4.81 × 10–2 |

| 318 | 0.226 | 123.9 | 0.917 | 2.71 × 10–3 | 1.46 × 10–2 | 5.41 × 10–2 |

| Temkin isotherm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (K) | bT | KT | R2 | χ2 | SSE | RMSE |

| 298 | 40.01 | 7.61 | 0.988 | 0.706 | 197.21 | 6.28 |

| 308 | 45.50 | 7.92 | 0.978 | 0.921 | 245.04 | 7.00 |

| 318 | 58.24 | 11.22 | 0.948 | 1.603 | 362.33 | 8.51 |

| Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (K) | qmax | E | R2 | χ2 | SSE | RMSE |

| 298 | 308.9 | 8.99 | 0.897 | 4.81 × 10–3 | 2.73 × 10–2 | 7.34 × 10–2 |

| 308 | 287.1 | 8.28 | 0.905 | 3.94 × 10–3 | 2.21 × 10–2 | 6.64 × 10–2 |

| 318 | 252.8 | 8.01 | 0.941 | 1.93 × 10–3 | 1.06 × 10–2 | 4.60 × 10–2 |

The results show that the Langmuir model is more suitable to describe the adsorption process of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH for mercury(II) ions. Meanwhile, the process is a monolayer adsorption, and there is no interaction between the adsorbent molecules. At the three temperatures of 298, 308, and 318 K, the maximum adsorption capacity fitted by the Langmuir model is 363.3, 330.0, and 280.9 mg/g, respectively. That is to say, the adsorption capacities of mercury(II) ions onto NiFe2O4-PAC-SH decrease with the increase in temperature. The three RL values of 0.027, 0.026, and 0.023 fitted by the Langmuir model are between 0 and 1, indicating a spontaneous and exothermic adsorption process.44

The values of 1/n in the Freundlich isotherm are less than 0.5, which indicates that the adsorption process is easy to occur and the adsorption capacities and strength are consistent with the above conclusion.45 The relatively big values of KT in the Temkin isotherm represent a relatively high adsorption potential between the adsorbent NiFe2O4-PAC-SH and mercury(II) ions. The values of bT increase with the increase in temperature, indicating that a low temperature is favorable for the adsorption of mercury(II) onto NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

For the Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm, the fitting results also reveal high R2 values. The three calculated values of average adsorption energy E are 8.99, 8.28, and 8.01 kJ/mol, which is between 8 and 16 kJ/mol, indicating that chemical adsorption is involved.14 The result may be due to the formation of complexation between negatively charged functional groups on the surface of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH and positively charged mercury(II) ions through covalent bond.46

3.5. Adsorption Thermodynamics

In general, the adsorption process involves thermodynamic parameters, including energy, enthalpy, and entropy. The changes of these parameters should be taken into account for analyzing the adsorption process. Three thermodynamic parameters of Gibbs free energy ΔG0 (kJ/mol), enthalpy change ΔH0 (kJ/mol), and entropy change ΔS0 (J/mol/K) are employed as follows

| 10 |

| 11 |

where R is the gas constant (8.314 J/mol/K), and KR is thermodynamic equilibrium constant.

Figure S2 shows the linear relationship between ln Kd and 1/T at different concentrations (20, 30, and 40 mg/L). The corresponding values of Gibbs free energy (ΔG0), entropy (ΔS0), and enthalpy (ΔH0) are calculated according to the fitting data, and the results are listed in Table 4. It can be seen that the three values of ΔH0 are all negative, indicating an exothermic adsorption process, which is consistent with the results fitted by isotherm adsorption.

Table 4. Thermodynamic Parameters for the Adsorption of Mercury(II) onto NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

| ΔG0 (kJ/mol) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C0 (mg/L) | ΔH0 (kJ/mol) | ΔS0 (J/mol/K) | 298 K | 308 K | 318 K |

| 20 | –14.37 | 12.11 | –17.95 | –18.15 | –18.19 |

| 30 | –13.82 | 12.65 | –17.56 | –17.79 | –17.80 |

| 40 | –13.21 | 14.06 | –17.36 | –17.63 | –17.63 |

The positive ΔS0 values of 12.11, 12.65, and 14.06 J/mol/K indicate the increase in disorder at the solid–liquid interface and that a low temperature is favorable for the adsorption of mercury(II) onto NiFe2O4-PAC-SH. All of the ΔG0 values are negative and less than 40 kJ/mol, which represents that the adsorption process of mercury(II) onto NiFe2O4-PAC-SH is spontaneous and involves some chemical reaction.14

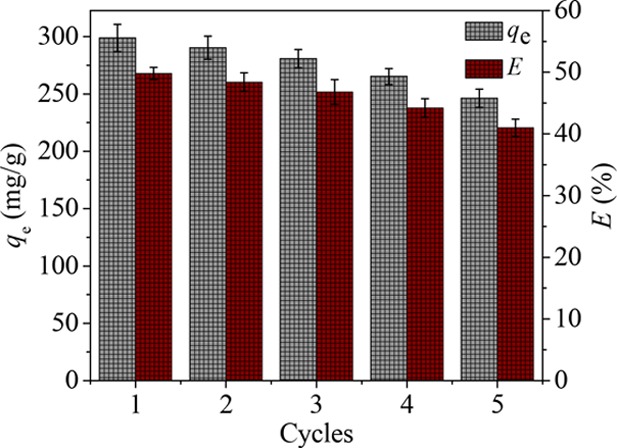

3.6. Regeneration Capability

That adsorbents can be used multiple times is an important factor to determine whether the adsorbent can be widely used. Hence, 0.1 M hydrochloric acid solution was employed as a regenerator to regenerate the NiFe2O4-PAC-SH after reaching the adsorption equilibrium.

From the data shown in Figure 12, the adsorption capacity of NiFe2O4-PAC-S is about 246.2 mg/g after five cycles and only reduces 17.6%. The result shows that the as-prepared adsorbent NiFe2O4-PAC-S has an outstanding regeneration performance and can be a promising adsorbent.

Figure 12.

Regeneration of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH after adsorption.

3.7. Mechanism Speculation

Figure 13 is the comparative FT-IR chromatogram of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH before and after adsorption of mercury(II) ions. It can be seen that the absorption peak of 1355 cm–1 increases obviously after the adsorption of mercury(II) ions, which is due to the electrostatic action of −COOH in the adsorption of mercury(II) ions.47 The result is consistent with the data of zeta potentials. It is also found that after the adsorption of mercury(II) ions, the −SH peak at 2363 cm–1 becomes weak, which is caused by the ion exchange between −SH groups and mercury(II) ions.14 These results suggest that −SH groups play an important role during the process of adsorption of mercury(II) ions onto NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

Figure 13.

FT-IR spectra of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH before and after adsorption.

In addition, the FT-IR chromatogram shown in Figure 13 also shows that the change of peak shape of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH is small before and after adsorption, which indicates that chemisorption is not the only effect factor and the electrostatic force can be another main factor based on the data of zeta potentials. Besides, Figure 13 also presents that the performance of as-prepared NiFe2O4-PAC-SH has a great hydrothermal stability.

In order to further analyze the reaction mechanism between the NiFe2O4-PAC-SH and mercury(II) ions, the NiFe2O4-PAC-SH containing adsorbed mercury(II) was characterized by XPS technology. Figure 14a is the XPS energy spectra of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH before and after the adsorption of mercury(II) ions.

Figure 14.

XPS spectra of (a) wide scan, (b) Hg 4f, and (c) S 2p after adsorption.

The appearance of a new Hg 4f peak and the weakened S 2p peak can be easily found on the diagram. From Figure 14b, the binding energies of Hg 4f5/2 and Hg 4f7/2 are 105.5 and 101.4 eV, respectively, which can be attributed to the HgCl2 adsorbed on the surface of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH. The above results prove that mercury(II) ions are successfully adsorbed on the surface of the material. In Figure 14c, it is found that the peaks of S 2p1/2 and S 2p3/2 shifted from high binding energies of 163.9 and 165.1 eV to low binding energies of 163.4 and 164.8 eV, respectively. The reason is due to S atoms in the −SH group that provide some electrons to the mercury atoms during the process of adsorption, forming the complexation of −S–Hg+ through covalent bond.14

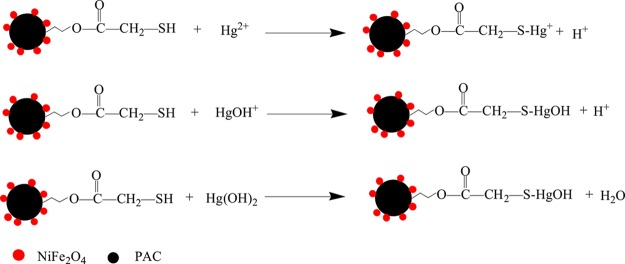

As we know, mercury(II) ions mainly exist in three morphologies in aqueous solution, namely, Hg2+, HgOH+, and Hg(OH)2.14 When the pH of aqueous solution is less than 3, there is mainly Hg2+ in the solution. Hg2+ can reduce with the increase in pH and finally disappear. On the contrary, the amounts of HgOH+ and Hg(OH)2 increase with the increase in pH. The number of HgOH+ reaches the maximum at pH 4. When the pH is greater than 6, Hg2+ almost disappears, and only a few of HgOH+ exist in the solution. Under the condition of high pH (over 8), Hg(OH)2 is the main form of existence. Figure 15 shows the schematic diagram of the possible adsorption mechanism of mercury(II) ions (Hg2+) onto NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

Figure 15.

Possible adsorption mechanism of mercury(II) onto NiFe2O4-PAC-SH.

Hg2+, HgOH+, and Hg(OH)2 combine with negatively charged NiFe2O4-PAC-SH to form NiFe2O4-PAC-S-Hg+ or NiFe2O4-PAC-S-HgOH through the way of ion exchange or electrostatic attraction. As more and more compounds with −S–Hg+ or −S–HgOH are formed, the further combination of Hg2+ with −SH will be prevented slightly due to the reduction of the number of active sites and electrical neutralization.

Moreover, according to the HSAB theory, the −SH group is a soft alkali, and mercury(II) is a soft acid. Therefore, the affinity between the −SH group and mercury(II) is very strong, and they can easily combine to form a stable complex, leading to a high removal of mercury.

4. Conclusions

To improve the adsorption performance and reduce the disposal cost, a novel thiol-modified magnetic activated carbon adsorbent of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH was successfully synthesized with a facile and safe hydrothermal method. The grafting of thiol groups was achieved by a simple esterification reaction with thioglycolic acid as the modified precursor, concentrated sulfuric acid as the catalyst, and acetic anhydride as the dehydrating agent. The magnetism was realized with a co-precipitation method by loading acid-resistant magnetic NiFe2O4 on the surface of PAC. The as-prepared NiFe2O4-PAC-SH can effectively and easily adsorb mercury(II) ions from aqueous solution. The maximal adsorption capacities from the experiment and Langmuir model achieve 298.8 and 366.3 mg/g at pH 7, respectively, exceeding other adsorptive materials. It is easy to separate the adsorbent of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH after adsorption from water through an external magnetic field. The data of kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics indicate that the adsorption of mercury(II) ions is spontaneous and exothermic and involves a chemical process. Ion exchange and electrostatic attraction are the main adsorption mechanism. Moreover, the as-prepared NiFe2O4-PAC-SH has an outstanding regeneration performance and remarkable stability, which is pretty favorable for the application of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH in the wastewater treatment. The whole experiment and analysis clearly exhibit that the NiFe2O4-PAC-SH can be an outstanding substitute for conventional activated carbon as an adsorbent.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51578354), Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Environmental Science and Engineering (No. Zd201705), Natural Science Research Project of Jiangsu Province Higher Education (No. 18KJA610002), Collaborative Innovation Center of Water Treatment Technology and Material of Jiangsu Province, Six Talent Peaks Program (No. 2016-JNHB-067), and Qing Lan Project of Jiangsu Province.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.9b00572.

Images of the three materials with N2 adsorption–desorption plot, pore size distribution and thermodynamic fitting, and table of the structure parameters with experimental data (PDF)

Video of the separation of NiFe2O4-PAC-SH from aqueous solution after adsorption under an external magnetic field (MP4)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wang Q.; Yang Z. Industrial water pollution, water environment treatment, and health risks in China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 358–365. 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Liu N.; Cao Y.; Zhang W.; Wei Y.; Feng L.; Jiang L. A facile method to prepare dual-functional membrane for efficient oil removal and in situ reversible mercury ions adsorption from wastewater. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 434, 57–62. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.09.230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hadi P.; To M.-H.; Hui C.-W.; Lin C. S. K.; McKay G. Aqueous mercury adsorption by activated carbons. Water Res. 2015, 73, 37–55. 10.1016/j.watres.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias Arias F. E.; Beneduci A.; Chidichimo F.; Furia E.; Straface S. Study of the adsorption of mercury (II) on lignocellulosic materials under static and dynamic conditions. Chemosphere 2017, 180, 11–23. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.03.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Jia J.; Guo Y.; Qu Z.; Liao Y.; Xie J.; Shangguan W.; Yan N. Design of 3D MnO2/Carbon sphere composite for the catalytic oxidation and adsorption of elemental mercury. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 342, 69–76. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu W.; Zhang W. Microwave-enhanced membrane filtration for water treatment. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 568, 97–104. 10.1016/j.memsci.2018.09.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gulgonul I.; Çelik M. S. Understanding the flotation separation of Na and K feldspars in the presence of KCl through ion exchange and ion adsorption. Miner. Eng. 2018, 129, 41–46. 10.1016/j.mineng.2018.08.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dallel R.; Kesraoui A.; Seffen M. Biosorption of cationic dye onto ″Phragmites australis″ fibers: Characterization and mechanism. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 7247–7256. 10.1016/j.jece.2018.10.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.; Yao Y.; Li X.; Lu J.; Zhou J.; Huang Z. Comparison of heavy metal removals from aqueous solutions by chemical precipitation and characteristics of precipitates. J. Water Pro. Eng. 2018, 26, 289–300. 10.1016/j.jwpe.2018.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siyal A. A.; Shamsuddin M. R.; Khan M. I.; Rabat N. E.; Zulfiqar M.; Man Z.; Siame J.; Azizli K. A. A review on geopolymers as emerging materials for the adsorption of heavy metals and dyes. J. Environ. Manage. 2018, 224, 327–339. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar A.; Hogland W.; Marques M.; Sillanpää M. An overview of the modification methods of activated carbon for its water treatment applications. J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 219, 499–511. 10.1016/j.cej.2012.12.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lou H.; Zhang Y.; Xiang Q.; Xu J.; Li H.; Xu P.; Li X. The real-time detection of trace-level Hg2+ in water by QCM loaded with thiol-functionalized SBA-15. Sens. Actuators, B Chem. 2012, 166-167, 246–252. 10.1016/j.snb.2012.02.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Zhang Z.; Zhao Y.; Xia K.; Guo Y.; Qu Z.; Bai R. A mild and facile synthesis of amino functionalized CoFe2O4@SiO2 for Hg(II) removal. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 673–693. 10.3390/nano8090673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y.; Jiang N.; Liu S.; Zheng C.; Wang X.; Huang T.; Guo Y.; Bai R. Thiol functionalization of short channel SBA-15 through a safe, mild and facile method and application for the removal of mercury (II). J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 5420–5433. 10.1016/j.jece.2018.08.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzyńska J.; Dobrowolski R.; Olchowski R.; Zięba E.; Barczak M. Palladium adsorption and preconcentration onto thiol- and amine-functionalized mesoporous silicas with respect to analytical applications. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 274, 127–137. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2018.07.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes H. T.; Miranda S. M.; Sampaio M. J.; Figueiredo J. L.; Silva A. M. T.; Faria J. L. The role of activated carbons functionalized with thiol and sulfonic acid groups in catalytic wet peroxide oxidation. Appl. Catal. B 2011, 106, 390–397. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.05.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Tao L.; Jiang M.; Gou G.; Zhou Z. Single-step synthesis of magnetic activated carbon from peanut shell. Mater. Lett. 2015, 157, 281–284. 10.1016/j.matlet.2015.05.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lompe K. M.; Menard D.; Barbeau B. The influence of iron oxide nanoparticles upon the adsorption of organic matter on magnetic powdered activated carbon. Water Res. 2017, 123, 30–39. 10.1016/j.watres.2017.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danalıoğlu S. T.; Bayazit Ö. S.; Kuyumcu Ş. K.; Salam M. A. Efficient removal of antibiotics by a novel magnetic adsorbent: Magnetic activated carbon/chitosan (MACC) nanocomposite. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 240, 589–596. 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.05.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C.; Zhu H.; Wang Q.; Wang J.; Cheng J.; Guo Y.; Zhou X.; Bai R. Adsorption of mercury(II) with an Fe3O4 magnetic polypyrrole–graphene oxide nanocomposite. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 18466–18479. 10.1039/C7RA01147D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H.; Shen Y.; Wang Q.; Chen K.; Wang X.; Zhang G.; Yang J.; Guo Y.; Bai R. Highly promoted removal of Hg(II) with magnetic CoFe2O4@SiO2 core-shell nanoparticles modified by thiol groups. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 39204–39215. 10.1039/C7RA06163C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guan T.; Zhao J.; Zhang G.; Zhang D.; Han B.; Tang N.; Wang J.; Li K. Insight into controllability and predictability of pore structures in pitch-based activated carbons. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 271, 118–127. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2018.05.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B. B.; Xu J. C.; Xin P. H.; Han Y. B.; Hong B.; Jin H. X.; Jin D. F.; Peng X. L.; Li J.; Gong J.; Ge H. L.; Zhu Z. W.; Wang X. Q. Magnetic properties and adsorptive performance of manganese–zinc ferrites/activated carbon nanocomposites. J. Solid State Chem. 2015, 221, 302–305. 10.1016/j.jssc.2014.10.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adeleke J. T.; Theivasanthi T.; Thiruppathi M.; Swaminathan M.; Akomolafe T.; Alabi A. B. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by ZnO/NiFe2O4 nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 455, 195–200. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.05.184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhaik A.; Raizada P.; Shandilya P.; Singh P. Magnetically recoverable graphitic carbon nitride and NiFe2O4 based magnetic photocatalyst for degradation of oxytetracycline antibiotic in simulated wastewater under solar light. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 3874–3883. 10.1016/j.jece.2018.05.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh T. A.; Tuzen M.; Sarı A. Magnetic activated carbon loaded with tungsten oxide nanoparticles for aluminum removal from waters. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2853–2860. 10.1016/j.jece.2017.05.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong D.; Zhou J.; Hu C.; Zhou Q.; Mao J.; Qin Q. Mercury removal mechanism of AC prepared by one-step activation with ZnCl2. Fuel 2019, 235, 326–335. 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.07.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Dai J.; Wang R.; Li F.; Wang W. Adsorption and desorption of divalent mercury (Hg2+) on humic acids and fulvic acids extracted from typical soils in China. Colloid. Surf. A. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2009, 335, 194–201. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2008.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J.; Liu H.; Zheng Y. M.; Qu J.; Chen J. P. Systematic study of synergistic and antagonistic effects on adsorption of tetracycline and copper onto a chitosan. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 344, 117–25. 10.1016/j.jcis.2009.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.; Cheng Z.; Ma W. Adsorption of Pb(II) from glucose solution on thiol-functionalized cellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 104, 807–809. 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.10.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingamdinne L. P.; Choi Y.-L.; Kim I.-S.; Yang J.-K.; Koduru J. R.; Chang Y.-Y. Preparation and characterization of porous reduced graphene oxide based inverse spinel nickel ferrite nanocomposite for adsorption removal of radionuclides. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 326, 145–156. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X.; Wang W.; Bi J.; Chen Y.; Hao X.; Sun X.; Zhang J. Morphology-controllable preparation of NiFe2O4 as high performance electrode material for supercapacitor. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 296, 181–189. 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.11.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G.; Sun Y.; Xu Y.; Zhang R. Catalytic performance of N-doped activated carbon supported cobalt catalyst for carbon dioxide reforming of methane to synthesis gas. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. E. 2018, 93, 234–244. 10.1016/j.jtice.2018.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo X. Q.; Chen W.; Yu A.; Le Xu M.; Cai J.; Chen Y.-X. pH effect on acetate adsorption at Pt(111) electrode. Electrochem. Commun. 2018, 89, 6–9. 10.1016/j.elecom.2018.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AlOmar M. K.; Alsaadi M. A.; Jassam T. M.; Akib S.; Hashim M. A. Novel deep eutectic solvent-functionalized carbon nanotubes adsorbent for mercury removal from water. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 497, 413–421. 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X.; Niu Y.; Zhang P.; Zhang C.; Zhang Z.; Zhu Y.; Qu R. Removal of Co(II) from fuel ethanol by silica-gel supported PAMAM dendrimers: Combined experimental and theoretical study. Fuel 2017, 199, 91–101. 10.1016/j.fuel.2017.02.076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J.; Niu Y.; Ren B.; Chen H.; Zhang S.; Jin J.; Zhang Y. Synthesis of Schiff base functionalized superparamagnetic Fe3O4 composites for effective removal of Pb(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solution. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 347, 574–584. 10.1016/j.cej.2018.04.151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh T. A.; Sarı A.; Tuzen M. Optimization of parameters with experimental design for the adsorption of mercury using polyethylenimine modified-activated carbon. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 1079–1088. 10.1016/j.jece.2017.01.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alijani H.; Shariatinia Z.; Aroujalian Mashhadi A. Water assisted synthesis of MWCNTs over natural magnetic rock: An effective magnetic adsorbent with enhanced mercury(II) adsorption property. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 281, 468–481. 10.1016/j.cej.2015.07.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oveisi F.; Nikazar M.; Razzaghi M. H.; Mirrahimi M. A.-S.; Jafarzadeh M. T. Effective removal of mercury from aqueous solution using thiol-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles. Environ. Nanotechnol., Monit. Manage. 2017, 7, 130–138. 10.1016/j.enmm.2017.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z.; Baird L.; Zimmerman N.; Yeager M. Heavy metal ion removal by thiol functionalized aluminum oxide hydroxide nanowhiskers. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 416, 565–573. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.04.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Wang Z.; Zhou X.; Bai R. Removal of mercury (II) from aqueous solution with three commercial raw activated carbons. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2017, 43, 2273–2297. 10.1007/s11164-016-2761-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Yuan X.; Wu Y.; Chen X.; Leng L.; Wang H.; Li H.; Zeng G. Facile synthesis of polypyrrole decorated reduced graphene oxide–Fe3O4 magnetic composites and its application for the Cr(VI) removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 262, 597–606. 10.1016/j.cej.2014.10.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Deng J.; Zhu J.; Zhou X.; Bai R. Removal of mercury(II) and methylene blue from a wastewater environment with magnetic graphene oxide: Adsorption kinetics, isotherms and mechanism. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 82523–82536. 10.1039/C6RA14651A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y.; Qu R.; Chen H.; Mu L.; Liu X.; Wang T.; Zhang Y.; Sun C. Synthesis of silica gel supported salicylaldehyde modified PAMAM dendrimers for the effective removal of Hg(II) from aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 278, 267–78. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X.; Niu Y.; Qiu Z.; Zhang Z.; Zhou Y.; Zhao J.; Chen H. Adsorption of Hg(II) and Ag(I) from fuel ethanol by silica gel supported sulfur-containing PAMAM dendrimers: Kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamics. Fuel 2017, 206, 80–88. 10.1016/j.fuel.2017.05.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Wu L.; Liu H.; Lan H.; Qu J. Improvement of aqueous mercury adsorption on activated coke by thiol-functionalization. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 228, 925–934. 10.1016/j.cej.2013.05.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.