Abstract

Purpose:

Assess associations of 2-year visual acuity (VA) outcomes with VA and optical coherence tomography central subfield thickness (CST) after 12 weeks of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for diabetic macular edema in DRCR.net Protocol T.

Design:

Randomized clinical trial.

Methods:

Setting: Multicenter (89 U.S. sites). Patient Population: Eyes with VA and CST data from baseline and 12-week visits (616 of 660 eyes randomized [93.3%]). Intervention: Six monthly injections of 2.0-mg aflibercept, 1.25-mg bevacizumab, or 0.3-mg ranibizumab; subsequent injections and focal/grid laser as needed for stability. Main Outcome Measures: Change in VA from baseline and VA letter score at 2 years.

Results:

Twelve-week VA response was associated with 2-year change in VA and 2-year VA letter score for each drug (P < .001) but with substantial individual variability (multivariable R2 = 0.38, 0.29, and 0.26 for 2-year change with aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab, respectively). Among eyes with less than 5-letter gain at 12 weeks, the percentages of eyes gaining 10 or more letters from baseline at 2 years were 42% (20 of 48), 31% (21 of 68), and 47% (28 of 59), and median 2-year VA was 20/32, 20/32, and 20/25, in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups respectively. Twelve-week CST response was not strongly associated with 2-year outcomes.

Conclusions and Relevance:

A suboptimal response at 12 weeks did not preclude meaningful vision improvement (i.e., ≥ 10-letter gain) in many eyes at 2 years. Eyes with less than 5-letter gain at 12 weeks often had good VA at 2 years without switching therapies.

Introduction

After initiating treatment for diabetic macular edema (DME) with the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab, visual acuity (VA) improves, on average, by 1 to 3 lines at 1 year.1–4 Vision typically stabilizes during the second year of treatment. However, the magnitude of VA change from baseline is highly variable among patients. Furthermore, many eyes do not have complete resolution of thickening following six monthly injections, especially with bevacizumab.5 In the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net) Protocol T, 51% to 73% of eyes (depending on the anti-VEGF agent used) were still thickened 12 weeks after initiating anti-VEGF therapy and 32% to 66% remained thickened at 24 weeks; however, median VA for these eyes at 2 years was 20/32 with each agent.5 Furthermore, eyes with persistent DME after 6 monthly injections typically had excellent VA outcomes through 2 to 3 years in both Protocol T and Protocol I, even if the persistent DME never resolved.5, 6

In 2016, Gonzalez et al.7 used publically available data from DRCR.net Protocol I participants treated with ranibizumab and prompt or deferred laser to explore associations between early (12-week) VA and optical coherence tomography (OCT) central subfield thickness (CST) responses with change in VA at 1 and 3 years.8, 9 They reported a strong association between early change in VA with change in VA at 1 and 3 years, but no significant association between the early CST response and later VA outcomes. In the subgroup in which the early vision response was less than 5 letters at 12 weeks (i.e., 1 month after the third consecutive monthly ranibizumab injection), 29% eventually improved by 10 or more letters from baseline at 3 years. In contrast, in the subgroup that experienced early improvement of 10 or more letters after three injections, 72% had improvement of 10 or more letters at 3 years.

Early indicators of long-term vision outcomes are of interest to both ophthalmologists and patients because of their potential to improve the counseling and management of individuals with DME. Data from Protocol I and other anti-VEGF trials10, 11 suggest that eyes with relatively large early improvements have better long-term change in vision, on average, than eyes that do not experience substantial early vision gains. However, these estimates are not precise enough to determine the course of vision gain or loss for an individual eye undergoing anti-VEGF therapy, nor do they provide evidence that switching to or adding alternative therapies other than focal/grid laser after just a few months of anti-VEGF would improve long-term outcomes.

To understand further the association of 12-week outcomes with VA outcomes at 1 and 2 years, we conducted a post hoc analysis of eyes treated for DME in a randomized clinical trial of three anti-VEGF agents (DRCR.net Protocol T).2, 3 The primary objectives were to determine if the previously described findings from Protocol I would be supported when ranibizumab was used with the treatment regimen of Protocol T and whether similar associations exist when using aflibercept or bevacizumab.

Methods

Methods for DRCR.net Protocol T have been published elsewhere with the complete protocol available online (www.drcr.net).2 The description that follows is summarized from a previous report.5 The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Study participants provided written informed consent. The protocol and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant informed consent forms were approved by the institutional review board associated with each participating center. Principal eligibility criteria included central-involved DME on clinical examination and OCT with a best-corrected electronic VA letter score of 78 through 24 (approximate Snellen equivalent 20/32 to 20/320) following protocol refraction.12

Visits were every 4 weeks through 52 weeks and every 4, 8, or 16 weeks thereafter depending on clinical course. The protocol required injections at baseline and every 4 weeks for the initial 20 weeks (6 injections). However, injections could be deferred if CST fell below sex and instrument-specific cutoffs (Heidelberg Spectralis ≥ 320 µm for men and ≥ 305 µm for women, Zeiss Cirrus ≥ 305 µm for men and ≥ 290 µm for women, Zeiss Stratus ≥ 250 µm for both sexes) and the VA letter score was 84 or better (approximate Snellen equivalent 20/20 or better) after two consecutive 4-week injections. After 20 weeks, injections were continued every 4 weeks if there was successive improvement or worsening in VA (≥ 5 letters) or CST (≥ 10% relative change). Otherwise, re-injection was withheld starting at 24 weeks if there was no improvement or worsening of VA or CST after two consecutive injections (sustained stability). Injections were resumed if there was subsequent worsening of VA or CST until sustained stability was attained again. Focal/grid laser was given at or after 24 weeks if DME persisted, the eye had not improved in VA or CST from the last two consecutive injections, and there were lesions amenable to photocoagulation. Alternative treatments, such as intravitreous corticosteroids, were not permitted unless failure criteria were met.

All eyes with complete VA and OCT data from baseline and 12 weeks were included in this analysis (616 of 660 [93.3%]). Mean change in VA from baseline or 12 weeks and VA letter scores were modeled with a general linear model. For multivariable analysis, each treatment group was evaluated separately because of the interaction between treatment group and baseline VA.2 Treatment group comparisons of mean change in VA and CST at 12 weeks were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Hochberg method.13 Within each treatment group, 3 cohorts of eyes were defined based on their improvement in VA from baseline at 12 weeks: less than 5 letters, 5 to 9 letters, and 10 or more letters. In addition, 3 cohorts of eyes were defined based on their reduction in CST between baseline and 12 weeks: less than 10%, 10% to less than 20%, and 20% or greater. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Association of Twelve-Week Response in Visual Acuity with Long-Term Vision Outcomes

Mean baseline VA letter score was 65 (approximate Snellen equivalent 20/50) in each group. Average change in VA from baseline at 12 weeks was greater with aflibercept than either bevacizumab (2.9-letter adjusted difference, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1 to 4.7 letters; P < .001) or ranibizumab (2.6-letter adjusted difference, 95% CI: 0.8 to 4.3 letters; P = .002). There was no statistically significant difference between bevacizumab and ranibizumab (−0.4-letter adjusted difference, 95% CI: −1.9 to 1.1 letters, P = .63). Similar trends were observed for dichotomous outcomes of less than 5-letter gain and 10-or-more-letter gain (Table 1).

Table 1.

Early (12-Week) Response of Visual Acuity and Central Subfield Thickness by Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Treatment Group.

| Aflibercept N = 209 | Bevacizumab N = 207 | Ranibizumab N = 200 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12-Week change in visual acuity | |||

| Mean ± SD, letters | 10.0 ± 9.1 | 7.2 ± 8.3 | 7.7 ± 8.4 |

| ≥ 10 letters, N (%) | 102 (48.8) | 68 (32.9) | 76 (38.0) |

| 5 to 9 letters, N (%) | 53 (25.4) | 62 (30.0) | 55 (27.5) |

| < 5 letters, N (%) | 54 (25.8) | 77 (37.2) | 69 (34.5) |

| 12-Week relative change in CST | |||

| Mean ± SD, % | −26.6 ± 18.5 | −16.8 ± 17.9 | −24.1 ± 20.1 |

| ≥ 20% decrease, N (%) | 123 (58.9) | 77 (37.2) | 109 (54.5) |

| 10% to < 20% decrease, N (%) | 53 (25.4) | 51 (24.6) | 43 (21.5) |

| < 10% decrease, N (%) | 33 (15.8) | 79 (38.2) | 48 (24.0) |

CST = central subfield thickness.

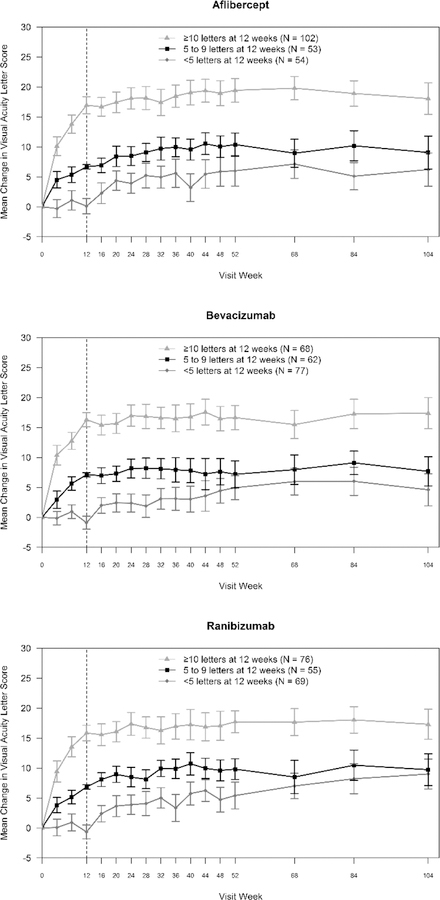

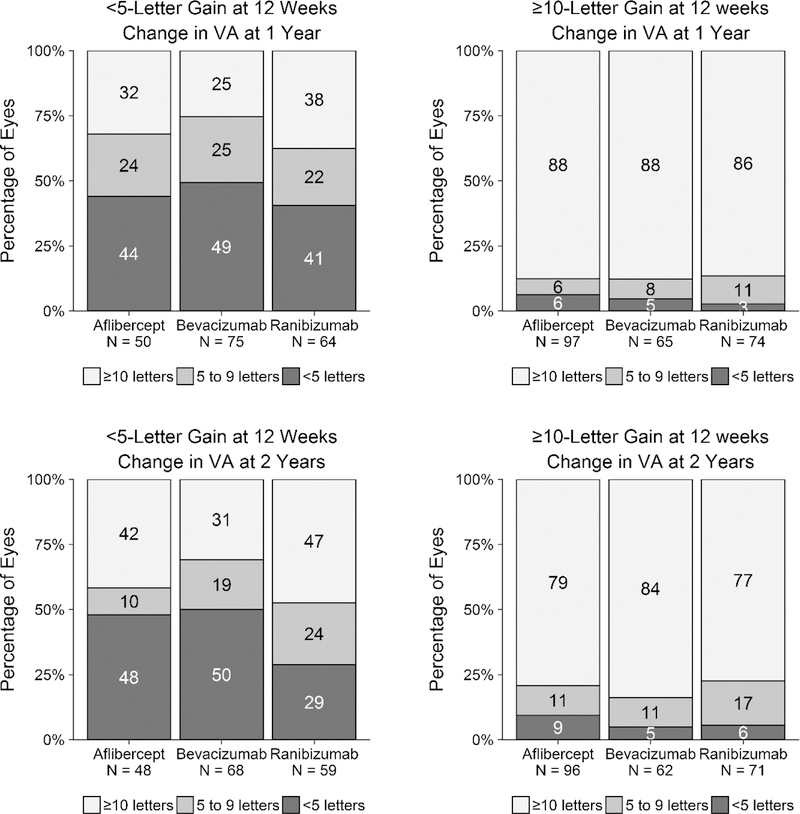

Eyes that gained less than 5 letters at 12 weeks had less VA improvement from baseline at 2 years, on average, than eyes that gained 10 or more letters at 12 weeks (aflibercept, 6.2 vs. 18.1; bevacizumab, 4.6 vs. 17.4; ranibizumab, 9.0 vs. 17.3, all P < .001, Figure 1). However, there was substantial individual variability of long-term change in VA within the early response cohorts as seen by the percentage of eyes gaining 10 or more letters from baseline (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Change in Visual Acuity from Baseline by Early (12-Week) Visual Acuity Response and Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Treatment Group.

Mean change in visual acuity letter score from baseline over 2 years by treatment group and 12-week visual acuity response. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Change in Visual Acuity from Baseline at 1 and 2 Years by Early (12-Week) Visual Acuity Response and Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Treatment Group.

Change in visual acuity letter score from baseline at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks.

Among eyes with less than 5-letter gain at 2 years, the absolute level of VA achieved by 2 years generally was very good (Supplemental Figure 1; Supplemental Material available at AJO.com). For example, the median VA at 2 years for eyes gaining less than 5 vs. 10 or more letters at 12 weeks was 20/32 vs. 20/25 for aflibercept, 20/32 vs. 20/25 for bevacizumab, and 20/25 vs. 20/32 for ranibizumab (Supplemental Table 1; Supplemental Material available at AJO.com). In addition, the absolute level of 2-year VA was generally very good for the subgroups of eyes gaining less than 5 letters at 12 weeks with baseline VA of 20/32 to 20/40 (median 20/25–20/32) and 20/50 to 20/320 (median 20/32–20/40; Supplemental Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 3; Supplemental Material available at AJO.com).

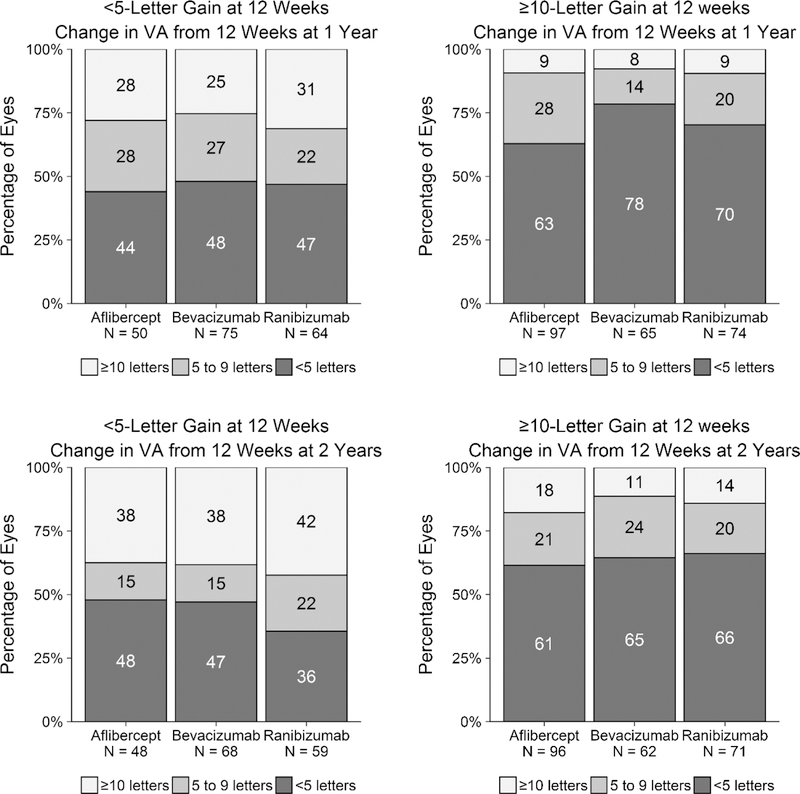

Eyes with limited initial gain (< 5 letters) from baseline at 12 weeks also were more likely to gain larger amounts of vision after 12 weeks than eyes with 10-or-more-letter initial gain. Specifically, among eyes with less than 5-letter vs. 10-or-more-letter gain at 12 weeks, the percentage of eyes gaining 10 or more additional letters from 12 weeks at 2 years was 38% (18 of 48) vs 18% (17 of 96) with aflibercept (P = .01), 38% (26 of 68) vs. 11% (7 of 62) with bevacizumab (P < .001), and 42% (25 of 59) vs. 14% (10 of 71) with ranibizumab (P < .001, Figure 3).

Figure 3. Change in Visual Acuity from 12 Weeks at 1 and 2 Years by Early (12-Week) Visual Acuity Response and Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Treatment Group.

Change in visual acuity letter score from 12 weeks at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks.

Results appeared similar for the subgroups of eyes with baseline VA of 20/32 to 20/40 and 20/50 to 20/320 (Supplemental Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure 5 for change from baseline, Supplemental Figure 6 and Supplemental Figure 7 for change from 12 weeks; Supplemental Material available at AJO.com). As expected, the potential for VA improvement in the subgroup with better VA (i.e., 20/32 to 20/40) was limited, presumably by a ceiling effect. For example, the percentage of eyes gaining 10 or more letters was uniformly lower for all treatment groups with better baseline VA (Supplemental Figures 4 and 6) compared with worse baseline VA (Supplemental Figures 5 and 7). Combining treatment groups, this ceiling effect was further evidenced by a moderate correlation between baseline VA and 12-week change in VA from baseline (r = −0.43, P < .001). In addition, median baseline VA was 20/40 for eyes with less than 5-letter gain at 12 weeks compared with 20/63 for eyes with 10-or-more-letter gain at 12 weeks.

Association of Twelve-Week Response in Central Subfield Thickness with Long-Term Vision Outcomes

Mean baseline CST ranged from 408 µm to 415 µm among treatment groups. The mean relative change in CST from baseline at 12 weeks (negative values reflect improvement) was better with aflibercept than bevacizumab (−9.6% adjusted difference, 95% CI: −13.3% to −5.9%; P < .001), but there was no statistically significant difference between aflibercept and ranibizumab (−1.9% adjusted difference, 95% CI: −5.0% to 1.2%; P = .22). Mean relative change was also better with ranibizumab than bevacizumab (−7.7% adjusted difference, 95% CI: −11.2% to −4.2%; P < .001). Similar trends were observed for dichotomous outcomes of less than 10% CST response and 20% or greater CST response (Table 1). Among eyes with less than 10% vs. 20% or greater CST response at 12 weeks, the percentage of eyes gaining 10 or more letters from baseline at 2 years was 56% (18 of 32) vs. 66% (74 of 112) with aflibercept (P = .40), 39% (28 of 71) vs. 66% (45 of 68) with bevacizumab (P = .002), and 58% (25 of 43) vs. 62% (59 of 95) with ranibizumab (P = .71; Supplemental Figure 8; Supplemental Material available at AJO.com).

Multivariable Regression Analysis of Long-Term Vision Outcomes

Multivariable linear regression was used to assess the associations of baseline VA, 12-week change in VA, baseline CST, and 12-week relative change in CST with change in VA from baseline at 1 and 2 years (Table 2). The 12-week change in VA was strongly associated with change in VA at 1 and 2 years in all treatment groups (P < .001; greater VA improvement more likely with greater improvement at 12 weeks). Baseline VA also had an effect in all scenarios although there was less confidence in the effect among bevacizumab-treated eyes at 1 year (P = .09, all other P < .05; greater VA improvement more likely with worse baseline vision). Neither baseline CST nor 12-week CST relative change had a significant effect on change in VA except in the ranibizumab group at 2 years (12-week relative change P = .02). Adjusted R2 values, which represent the amount of variability in overall vision gain explained by the combined effect of these VA and CST variables, ranged from 0.33 to 0.63 at 1 year and from 0.26 to 0.38 at 2 years.

Table 2.

Multivariable Analysis of Change in Visual Acuity from Baseline at 1 and 2 Years by Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Treatment Group.

| Characteristic | 1 Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aflibercept

N = 199 |

Bevacizumab

N = 199 |

Ranibizumab

N = 192 |

||||

| Estimate* | P-value | Estimate | P-value | Estimate | P-value | |

| Baseline VA | −0.30 | < .001 | −0.11 | .09 | −0.14 | .005 |

| 12-wk VA change | 0.57 | < .001 | 0.59 | < .001 | 0.69 | < .001 |

| Baseline CST (per 10 µm) | 0.05 | .30 | −0.10 | .06 | −0.02 | .70 |

| 12-wk CST relative change | −0.04 | .21 | −0.07 | .08 | −0.01 | .72 |

| Full Model R2 | 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.45 | |||

| 2 Years | ||||||

| N = 193 | N = 180 | N = 177 | ||||

| Baseline VA | −0.38 | < .001 | −0.19 | .02 | −0.29 | < .001 |

| 12-wk VA change | 0.46 | < .001 | 0.57 | < .001 | 0.46 | < .001 |

| Baseline CST (per 10 µm) | 0.09 | .23 | −0.05 | .44 | 0.06 | .35 |

| 12-wk CST relative change | 0.06 | .21 | −0.06 | .22 | 0.10 | .02 |

| Full Model R2 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.26 | |||

Abbreviations: CST = central subfield thickness; VA = visual acuity.

Average change in VA associated with a 1-unit change in each characteristic (e.g., 1 letter of VA, 10 µm of CST, or 1% CST relative change)

The associations of 1- and 2-year VA letter scores with the same variables also were assessed (Supplemental Table 2; Supplemental Material available at AJO.com). Results were similar to the analyses of change in VA from baseline. Both baseline VA and 12-week VA change were strongly associated with 1-year and 2-year VA letter score (P < .001 for all scenarios). Adjusted R2 values ranged from 0.47 to 0.61 at 1 year and from 0.22 to 0.38 at 2 years.

With respect to change in VA from 12 weeks at 1 and 2 years, similar analyses were conducted but substituted 12-week VA and CST in place of baseline VA and CST (Supplemental Table 3; Supplemental Material available at AJO.com). The effect of 12-week VA was significant in all groups ( P < .05; better 12-week VA associated with less VA gain); however, the importance of change from baseline at 12 weeks was variable (P = .12, < .001, and, .02 at 1 year and .92, .06, and .02 at 2 years for aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab, respectively). Adjusted R2 values ranged from 0.08 to 0.24 at 1 year and from 0.08 to 0.23 at 2 years.

Discussion

The mean change in VA from baseline at 12 weeks among all 3 anti-VEGF agents was associated with long-term visual acuity outcomes when treating DME with aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab. On average, eyes with less VA gain at 12 weeks had less VA gain from baseline and lower VA letter score at 2 years. However, long-term VA gain in individual eyes varied substantially and only about one quarter to one half of the variability in long-term vision outcomes was explained by the combined effects of baseline VA and CST and 12-week change in VA and CST. Thus, predictions for an individual based on 12-week VA are difficult, despite correlation at a group level. This variability in long-term outcomes was especially apparent when the 12-week response was less than 5 letters gained as 42%, 31%, and 47% of these eyes eventually gained 10 or more letters at 2 years when treated with aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab, respectively. In contrast, baseline CST and 12-week CST response had far less association with long-term VA outcomes than baseline or 12-week change in VA.

These analyses from Protocol T show that the previously described association of early VA response with later VA outcomes in eyes treated with ranibizumab for DME7, 14 extends to eyes treated with aflibercept or bevacizumab. Nevertheless, differences in the treatment regimens of Protocol I and Protocol T could have contributed to differences between the reports. First, Protocol T only allowed focal/grid laser starting at 6 months among eyes with persistent but stable DME, whereas half of the eyes in Protocol I assigned to ranibizumab at baseline also were assigned randomly to receive prompt focal/grid laser at baseline. Second, resumption of anti-VEGF for worsening of DME or worsening of VA in the presence of DME was required in Protocol T, whereas it was at investigator discretion in Protocol I.

Another post hoc report from Protocol T presented complementary results that support the use of a structured, long-term anti-VEGF treatment regimen for DME in eyes with limited initial response.5 First, it showed continued resolution of DME in eyes through 24 weeks with continued monthly anti-VEGF injections. Furthermore, eyes with chronic persistent DME at 2 years still had relatively good VA compared with eyes in which DME resolved (median 20/25 to 20/32 among all treatment groups with and without chronic persistent DME). This current report shows continued VA gains in many eyes despite limited initial response and good VA at 2 years even with less than 5-letter response at 12 weeks.

It remains unknown at this time whether eyes with less than 5-letter VA gain and persistent DME after 3 consecutive injections would have greater benefit if switched to alternative therapies. However, it should be noted that the absolute level of VA was very good at 2 years (median 20/25–20/32), which sets a high bar to surpass with alternative therapies. An ophthalmologist might not want to consider switching to or adding alternative therapies if there was little additional VA to gain.

Such questions might best be answered by a randomized clinical trial in which the DRCR.net structured treatment regimen for DME is compared with a regimen that involves switching to or adding another treatment after a suboptimal response at 12 weeks. As an example, in the DRCR.net Protocol U, the addition of sustained release dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex®) to ranibizumab was compared among eyes that had persistent DME despite at least 3 recent anti-VEGF injections and 3 additional ranibizumab injections during a 12-week run-in phase. At 24 weeks after the run-in phase, however, there was no significant difference between the groups for the primary outcome of change in visual acuity from baseline.15

As with previous analyses from Protocol T, bias should have been limited by excellent retention (over 90% through 2 years), masked VA examiners at annual visits, and objective OCT data used to guide retreatment.3 However, given the post hoc nature of these analyses, the results should be viewed as exploratory. Furthermore, outcomes were evaluated without adjustment for multiplicity. In addition, because a single measurement is prone to variability, a clinician should be cautious before deeming someone a poor responder at 12 weeks. Due to variability in measurement of VA, the change in VA of an eye may fall into different categories of improvement (< 5, 5–9, ≥10 letters) over time when there is no real change. For example, eyes with scores in the less than 5-letter category at 12 weeks may later be in categories of more improvement when there was no real change because of regression to the mean.16

Conclusions

In summary, the VA response at 12 weeks following 3 consecutive anti-VEGF injections was positively associated with 2-year vision outcomes. However, a suboptimal response at 12 weeks did not preclude further meaningful vision improvement (i.e., ≥ 10-letter gain) from occurring in many eyes. In addition, eyes with less than 5-letter gain from baseline at 2 years typically had very good VA at 2 years (median 20/25–20/32) without using alternative therapies, in part because they were more likely to start with good vision. Currently, there is little evidence to suggest that switching from the DRCR.net anti-VEGF regimen to other regimens will result in better results than those reported in Protocol T.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Visual acuity at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks.

Supplemental Figure 2: Visual acuity at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks among eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/32 to 20/40 (approximate Snellen equivalent).

Supplemental Figure 3: Visual acuity at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks among eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/50 to 20/320 (approximate Snellen equivalent).

Supplemental Figure 4: Change in visual acuity letter score from baseline at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks among eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/32 to 20/40 (approximate Snellen equivalent).

Supplemental Figure 5: Change in visual acuity letter score from baseline at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks among eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/50 to 20/320 (approximate Snellen equivalent).

Supplemental Figure 6: Change in visual acuity letter score from 12 weeks at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks among eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/32 to 20/40 (approximate Snellen equivalent).

Supplemental Figure 7: Change in visual acuity letter score from 12 weeks at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks among eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/50 to 20/320 (approximate Snellen equivalent).

Supplemental Figure 8: Change in visual acuity letter score from baseline at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes with less than 10% (top left, bottom left) and 20% or greater decrease (top right, bottom right) in OCT central subfield thickness at 12 weeks.

Highlights.

Early visual response to anti-VEGF for DME is associated with later vision outcomes

Limited 12-week vision gain did not preclude meaningful 2-year gain in many eyes

Eyes with < 5-letter 12-week gain typically had good (20/25–20/32) 2-year vision

Results do not support switching from this DRCR.net anti-VEGF regimen over 2 years

Studies of switching regimens should be compared with this DRCR.net anti-VEGF regimen

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Neil M. Bressler: Alkeus, American Medical Association, Bayer, Chiltern Intl Inc. Novartis, Roche, Samsung (Grants)

Wesley T. Beaulieu: Regeneron, Genentech (Grants)

Maureen G. Maguire: Genentech/Roche (honoraria)

Adam R. Glassman: Regeneron, Genentech (Grants)

Kevin J. Blinder: Regeneron, Allergan, Bausch & Lomb (Consultancy)

Susan B. Bressler: Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Roche, Merck (Grants)

Victor H. Gonzalez: Regeneron (Grants, Speaker, Consultant), Genentech (Grants, Speaker, Consultant)

Lee M. Jampol: Quintiles/Stem Cell Organization (Consultancy)

Michele Melia: None

Jennifer K. Sun: Genentech (Grants), Optovue, Inc. (Other), Novo Nordisk (Travel, Meeting Expenses), KalVista (Grants), Boehringer-Ingelheim (Grants), Adaptive Sensory Technology (Other), Boston Micromachines (Other), Current Diabetes Reports (Board Membership), JAMA Ophthalmology (Board Membership, payments for manuscript preparation), Adaptive Sensory Technology (Grants)

John A. Wells: Genentech (Consultancy, clinical or lab research grants, development of presentations. Opthea, KalVista, Ohr Pharmaceutical, NIH (Grants). Iconic Pharm. (Consultancy); Regeneron (Grants)

Funding/Support: Supported through a cooperative agreement from the National Eye Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services EY14231, EY23207, EY18817.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding organization (National Institutes of Health) participated in oversight of the conduct of the study and review of the manuscript but not directly in the design or conduct of the study, nor in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Previous Presentations: None.

Contributor Information

Neil M. Bressler, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

Wesley T. Beaulieu, Jaeb Center for Health Research, Tampa, Florida.

Maureen G. Maguire, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Adam R. Glassman, Jaeb Center for Health Research, Tampa, Florida.

Kevin J. Blinder, The Retina Institute, St Louis, Missouri.

Susan B. Bressler, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

Victor H. Gonzalez, Valley Retina Institute, McAllen, Texas

Lee M. Jampol, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, Illinois.

Michele Melia, Jaeb Center for Health Research, Tampa, Florida.

Jennifer K. Sun, Joslin Diabetes Center, Beetham Eye Institute, Harvard Department of Ophthalmology, Boston, Massachusetts.

John A. Wells, III, Palmetto Retina Center, Columbia, South Carolina.

References

- 1.Nguyen QD, Brown DM, Marcus DM, et al. Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: Results from 2 phase III randomized trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology 2012;119:789–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, Wells JA, Glassman AR, et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: two-year results from a comparative effectiveness randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology 2016;123:1351–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DM, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Do DV, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema: 100-week results from the VISTA and VIVID studies. Ophthalmology 2015;122:2044–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bressler NM, Beaulieu WT, Glassman AR, et al. Persistent macular thickening following intravitreous aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for central-involved diabetic macular edema with vision impairment: A secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136:257–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bressler SB, Ayala AR, Bressler NM, et al. Persistent macular thickening after ranibizumab treatment for diabetic macular edema with vision impairment. JAMA Ophthalmology 2016;134:278–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez VH, Campbell J, Holekamp NM, et al. Early and long-term responses to anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in diabetic macular edema: analysis of Protocol I data. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;172:72–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research N, Elman MJ, Aiello LP, et al. Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2010;117:1064–77 e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research N, Elman MJ, Qin H, et al. Intravitreal ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema with prompt versus deferred laser treatment: three-year randomized trial results. Ophthalmology 2012;119:2312–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ying GS, Maguire MG, Daniel E, et al. Association of Baseline Characteristics and Early Vision Response with 2-Year Vision Outcomes in the Comparison of AMD Treatments Trials (CATT). Ophthalmology 2015;122:2523–31 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pieramici D, Singh RP, Gibson A, et al. Outcomes of diabetic macular edema eyes with limited early response in the VISTA and VIVID studies. Ophthalmology Retina 2017. 10.1016/j.oret.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck RW, Moke PS, Turpin AH, et al. A computerized method of visual acuity testing: adaptation of the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study testing protocol. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;135:194–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hochberg Y. A sharp er Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 1988;75:800–2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bressler SB, Qin H, Beck RW, et al. Factors associated with changes in visual acuity and central subfield thickness at 1 year after treatment for diabetic macular edema with ranibizumab. Arch Ophthalmol 2012;130:1153–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maturi RK, Glassman AR, Liu D, et al. Effect of adding dexamethasone to continued ranibizumab treatment in patients with persistent diabetic macular edema: A DRCR Network phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136:29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferris FL 3rd, Maguire MG, Glassman AR, et al. Evaluating effects of switching anti-vascular endothelial growth factor drugs for age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;135:145–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Visual acuity at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks.

Supplemental Figure 2: Visual acuity at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks among eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/32 to 20/40 (approximate Snellen equivalent).

Supplemental Figure 3: Visual acuity at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks among eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/50 to 20/320 (approximate Snellen equivalent).

Supplemental Figure 4: Change in visual acuity letter score from baseline at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks among eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/32 to 20/40 (approximate Snellen equivalent).

Supplemental Figure 5: Change in visual acuity letter score from baseline at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks among eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/50 to 20/320 (approximate Snellen equivalent).

Supplemental Figure 6: Change in visual acuity letter score from 12 weeks at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks among eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/32 to 20/40 (approximate Snellen equivalent).

Supplemental Figure 7: Change in visual acuity letter score from 12 weeks at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes gaining fewer than 5 (top left, bottom left) and 10 or more letters (top right, bottom right) at 12 weeks among eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/50 to 20/320 (approximate Snellen equivalent).

Supplemental Figure 8: Change in visual acuity letter score from baseline at 1 (top left, top right) and 2 years (bottom left, bottom right) for eyes with less than 10% (top left, bottom left) and 20% or greater decrease (top right, bottom right) in OCT central subfield thickness at 12 weeks.