Summary

Drug resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) represents a major programmatic challenge at the national and global level. Only ~30% of patients with multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB were diagnosed and ~25% were initiated on therapy for MDR-TB in 2016. Increasing evidence now points towards primary transmission of DR-TB rather than inadequate treatment as the major driver of the DR-TB epidemic. The cornerstone of DR-TB transmission prevention should be earlier diagnosis and prompt initiation of effective treatment for all patients with DR-TB. Despite the extensive scale up of Xpert MTB/RIF testing, major implementation barriers continue to limit its impact. Although there is longstanding evidence in support of the rapid impact of treatment on patient infectiousness, delays in the initiation of effective DR-TB treatment persist, resulting in ongoing transmission. However, it is also imperative to address the burden of latent DR-TB infection, since it is estimated that many DR-TB patients will become infectious prior to seeking care and encounter various diagnostic delays before treatment. Addressing latent DR-TB primarily consists of identifying, treating and following contacts of patients with MDR-TB, typically through household contact evaluation. Adjunctive measures such as improved ventilation and use of germicidal ultraviolet (GUV) technology can further decrease TB transmission in high-risk congregate settings. Although many gaps remain in our biological understanding of TB transmission, implementation barriers to early diagnosis and rapid initiation of effective DR-TB treatment can and must be overcome if we are to impact DR-TB incidence in the short and long-term.

Keywords: tuberculosis, MDR, transmission, active case finding

Background

Drug resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) represents a major programmatic challenge at the national and global level and a serious danger to people living in TB endemic countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that of the 490 000 people estimated to have developed multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) in 2016 (with an additional 110 000 cases of rifampicin [RMP]-resistant TB), only ~30% were diagnosed and ~25% were initiated on treatment for MDR-TB1.

For decades, it was thought that DR-TB strains were relatively less transmissible than drug susceptible strains, which drove global policy to focus on the management of drug susceptible TB (DS-TB). Experiments using animal models in the 1950s demonstrated that some DR-TB (predominantly isoniazid-[INH] resistant) strains were less pathogenic than DS-TB strains2, 3. However, although drug resistance mutations can impair fitness in laboratory settings, clinical strains that cause disease (by definition) have to be virulent and may have undergone compensatory mutations that restore fitness4.

Various modeling studies have demonstrated heterogeneity in the fitness of DR-TB strains, highlighting that even a small number of relatively fit DR-TB strains can outcompete DS-TB and less fit DR-TB strains5, 6. Epidemiological studies have shown conflicting results with some demonstrating a 50% reduction in transmission of MDR-TB to household contacts compared to DS-TB7. However, other household contact studies demonstrated high rates of TB disease and infection if index patients had DR-TB strains8–10. Global TB policy guidance now recommends early diagnosis, including assessment for drug resistance, and prompt, effective treatment for all patients with TB11.

Until recently, DR-TB transmission prevention efforts have focused primarily on decreasing acquisition of drug resistance due to poor adherence to first line TB treatment. However, increasing evidence now points towards primary transmission of DR-TB rather than inadequate treatment as the main driver of the DR-TB epidemic. Genotypic analyses from a large study in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, evaluating extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB demonstrated that 69% of patients with XDR-TB had never received prior treatment for MDR-TB12. Cluster analyses showed that 30% had identifiable evidence of person-to-person and hospital-based transmission, although known epidemiological links were not established for the majority of transmitted cases. A large epidemiological study from Shanghai, China, which, in contrast to KwaZulu-Natal, is a low HIV prevalence setting, reported that 70% of MDR-TB cases arose from transmission13. Less easily measured is the number of previously treated patients who become re-infected with MDR-TB, including those who are re-infected with the same circulating MDR-TB strain (often misclassified as ‘reactivation’, thus underestimating transmission estimates). Exogenous reinfection may account for as much as 60% of recurrent TB14. The high proportion of undiagnosed patients with MDR-TB is likely to be a major driver of TB transmission and also limits understanding of where and how transmission occurs since these patients are not included in analyses.

Here, we focus on the role of prompt and effective treatment as the most important tenet of MDR-TB transmission prevention. We do so by addressing the approach to treatment in several categories: the scientific basis for early diagnosis and treatment of active MDR-TB disease as a transmission prevention approach (including the probable role of surgery); preventive therapy for MDR-TB for household contacts and others with known exposure to MDR-TB; active or enhanced case finding interventions focused on congregate settings; the neglected management of patients with refractory or incurable DR-TB to prevent transmission; and other adjunctive interventions to decrease transmission.

Early diagnosis and initiation of effective treatment for all patients with drug-resistant TB

As is the case for TB transmission prevention overall, the cornerstone of MDR-TB transmission prevention should focus on earlier diagnosis and prompt initiation of effective therapy for all patients with DR-TB, since transmission is driven by patients with unsuspected DR-TB (this includes patients on treatment for DS-TB who have undiagnosed DR-TB as well as those who remain both undiagnosed and untreated)15. This strategy will improve individual outcomes and decrease transmission by rendering these patients non-infectious. The WHO’s End TB Strategy, launched in 2015, sets out an ambitious agenda to achieve its targets, which includes a 90% reduction in TB incidence11. The End TB Strategy calls for universal drug susceptibility testing (DST) for all persons being evaluated for TB, and not only those with known risk factors for DR-TB disease. This strategy requires massive scale-up of implementation of molecular diagnostics for TB that enable an initial assessment for drug resistance at the time of TB diagnosis.

Although WHO recommends Xpert MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) as the initial test for all persons being evaluated for TB16, only 15 of the 29 high TB incidence countries currently recommend Xpert for this use17. Scale up of Xpert has been hindered by high costs, weak infrastructure and inadequate implementation plans that include quality assurance and maintenance support18. A large multicenter cohort study conducted in 18 countries reported that only 4% of patients with HIV-TB co-infection had undergone Xpert testing19. Additionally, if Xpert reveals evidence of rifampicin resistance, prompt second-line DST should be initiated to prevent ongoing transmission from undetected XDR-TB. A study from South Africa demonstrated that only 44% of 1332 patients with rifampicin-resistant TB had second-line DST for both fluoroquinolones (FQs) and second-line injectable agents20.

Other existing diagnostic assays, which include an assessment for drug resistance such as line probe assays (LPA)21 or the microscopic observation of drug susceptibility (MODS) assay,22 require significant technical expertise and laboratory infrastructure, which limit their impact as initial diagnostic tests. Xie et al. recently published promising results for a new automated cartridge-based molecular TB assay that detected resistance to FQs, aminoglycosides and INH directly from sputum specimens (83% sensitivity for INH, 88%−92% sensitivity for moxifloxacin depending on the critical concentration used, 71% sensitivity for kanamycin and 71% sensitivity for amikacin, with an average specificity of 94%)23. These sensitivities all increased to >90% and specificity rose to 99% when DNA sequencing rather than phenotypic DST was used as the reference standard. Further work is in progress to develop this assay.

There is interest in the potential for whole genome sequencing (WGS) to enable the rapid delivery of ‘personalized’ DR-TB regimens and improved investigation of transmission events in outbreak scenarios. A study which implemented a WGS-based diagnostic system in eight laboratories in Europe and North America reported that full WGS results could be generated in a median of 9 days versus 31 days for final reference laboratory results at a lower cost24. One case of MDR-TB and a new cluster of MDR-TB was diagnosed through WGS prior to the completion of the routine diagnostic workflow, enabling treatment to be initiated more rapidly. However sequencing was performed on newly positive liquid cultures, which are not routinely obtained in most high DR-TB incidence settings due to resource and infrastructure limitations. Public Health England is the first program to perform WGS on all strains isolated in routine clinical practice in the United Kingdom but the impact on individual and programmatic care is unknown.

Data on the impact of TB treatment on infectiousness are primarily derived from studies using the human-to-guinea-pig model, established by Richard Riley and colleagues in the late 1950s, which demonstrate that transmission is stopped by effective treatment25, 26. More recently, using a human-to-guinea-pig model in South Africa, Dharmadhikari et al. showed that only 1% of guinea pigs (1/90) developed TB after being exposed to patients with MDR-TB who were on effective treatment over a three-month period, and that transmission occurred from patients with unsuspected XDR-TB27.

As stated above, MDR-TB incidence is primarily driven by transmission from patients with undiagnosed and untreated (or ineffectively treated) MDR-TB. A 2007 study from Russia demonstrated that patients who had any part of their TB treatment in hospital had a substantially higher risk of developing MDR-TB than equally adherent patients treated on an ambulatory basis (hazard ratio 6.3)28. During the months that it took to observe treatment failure on treatment for DS-TB, patients with unsuspected MDR-TB transmitted their infection, thereby re-infecting patients with DS-TB. More recently, Xpert testing was applied to all new TB admissions to two TB hospitals in Russia15. Those testing positive were treated for MDR-TB within just a few days. Compared to historical control cohorts in the same hospital, there was a 78% odds reduction in the risk of developing MDR-TB. These data support the hypothesis that by reducing the period of exposure to untreated MDR-TB, MDR-TB incidence will fall.

A recent study using a transmission model based on data from Vietnam indicated that if all identified patients with active TB, who had been treated previously, underwent DST, and 85% of those diagnosed with MDR-TB initiated treatment, based on current MDR-TB treatment success rates, MDR-TB incidence in 2025 could be reduced by 26% (95% uncertainty range [UR] 4–52%) due to the impact of effective treatment on transmission29. The authors went on to model a scenario in which all patients with active TB diagnosed with MDR-TB received a novel treatment regimen with similar effectiveness and tolerability as current treatment for DS-TB, and showed that MDR-TB incidence could be reduced by 54% (95% UR 20–74%) by 2025.

Increasing evidence, primarily from observational cohort studies, suggests that regimens that include new drugs such as bedaquiline (BDQ) and delamanid (DLM) or repurposed drugs such as linezolid and clofazimine can improve DR-TB outcomes, including culture conversion, treatment success and mortality30–32. However, some observational cohort data have demonstrated high rates of reversion of culture conversion in patients with FQ-resistant TB, suggesting that longer durations (more than 6 months) of BDQ may be required for patients with more resistant disease33. Interim data from the EndTB phase III clinical trial have shown that 79% of the 658 patients included in the DLM analysis achieved culture conversion, and safety analyses did not demonstrate any major safety issue with either BDQ or DLM. Data from the arms of the randomized controlled STREAM (Short-course treatment for multidrug-resistant TB) trial, which include BDQ-containing regimens, are eagerly awaited34.

Surgery to reduce drug-resistant TB transmission

Patients with localized pulmonary DR-TB that is refractory to chemotherapy and marked by persistent smear and culture positivity represent a transmission risk. These patients often have extensive pulmonary disease, with cavitary lesions and areas of scarring35. Anti-TB drugs have variable sterilizing activity in pulmonary cavitary lesions, which may create conditions for the amplification of drug resistance, unrestricted bacterial growth and generation of infectious aerosols containing DR-TB strains36.

Surgery has been used as an adjunct to chemotherapy to manage patients with DR-TB who have a high risk of failure or relapse, often due to smear positivity and/or cavitary disease, particularly in those with XDR-TB. Candidates for surgery typically have unilateral disease (although some with apical bilateral disease may be considered) and adequate pulmonary reserve16.

The goal of the surgical procedure is removal of infected and devitalized pulmonary parenchyma, with the extent of resection (pneumonectomy, segmentectomy, lobectomy, wedge resection) depending on disease extent. Excision of cavities has been hypothesized to decrease the overall mycobacterial burden, but also to remove areas with a high concentration of DR-TB bacilli, thereby enhancing the response to postoperative chemotherapy37, 38.

It has been reported that resection reduces infectiousness, as evidenced by sustained conversion of persistently positive smear and culture to negative39–41. Meta-analysis based on observational data have also demonstrated improved outcomes for patients with DR-TB, particularly XDR-TB, who received surgical intervention compared to medical treatment alone42, 43. Several questions, such as the optimal timing for surgery, duration of pre- and postoperative chemotherapy and use of adjunctive investigations such as positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET/CT) remain44. Nonetheless, surgical centers with the requisite expertise to perform these surgical procedures are scarce and often inaccessible. Surgery for DR-TB also presents its own risk of transmission in the operating room and recovery area45.

Treatment of latent multidrug-resistant TB infection

Although household transmission may only account for between 8% and 19% of the overall proportion of TB transmission in high TB and HIV incidence settings46, reducing TB transmission within the household continues to represent an important (and more easily actionable) focus for TB transmission prevention efforts, which is emphasized in low-incidence settings. Once an index patient has been diagnosed with TB, at a minimum, all household contacts should be screened for active TB disease, given the high yield of active case finding among household contacts9. This is particularly relevant for decreasing MDR-TB transmission because 75% of people estimated to have MDR-TB are not diagnosed1 and those who are diagnosed often experience diagnostic delays47. There is a strong evidence base for the treatment of latent DS-TB;48 however, evidence to inform recommendations for preventive MDR-TB therapy is limited.

Although there is a lack of data from randomized clinical trials, the WHO updated its latent TB guidelines in 2018 to state that preventive therapy (regimen to be based on source DST) for selected high-risk contacts (children, people on immunosuppressive therapy or people with HIV) of patients with MDR-TB may be considered, based on individualized risk assessment and sound clinical justification49. The WHO recommendation also states that strict clinical observation and close monitoring for the development of active TB disease for at least 2 years are required regardless of the provision of preventive therapy. Similarly, a consensus paper issued by a group of experts in 2015 recommended considering FQ preventive therapy in high-risk contacts (at least child contacts aged <5 years and immunocompromised persons of any age) with either levofloxacin (LVX) if the source patient’s DST confirmed FQ susceptibility or if background FQ resistance was low, or moxifloxacin if DST confirmed ofloxacin resistance or background FQ resistance was high50. This expert group also considered concurrent treatment with INH to treat co-infection with a DS-TB strain and for adjunctive therapy against MDR-TB strains if given at a high dose. A systematic review by Marks et al. in 2017 found that, despite limited data (6 studies comparing outcomes for persons treated and untreated for latent MDR-TB infection), there was a reduced risk of TB incidence with treatment of latent MDR-TB infection. Treatment discontinuation rates were high with pyrazinamide-containing regimens. Although the most effective regimen was FQ, combined with ethionamide, this regimen was more expensive than others and not considered cost-effective. FQ and ethambutol was the most effective, followed by FQ alone, then by pyrazinamide and ethambutol51.

Three randomized controlled trials that evaluate different regimens for MDR-TB preventive therapy are underway, although results are not anticipated until at least 202052. The TB-CHAMP (Tuberculosis child multidrug-resistant preventive therapy) study, based in South Africa, will evaluate six months of LVX vs. placebo in children aged <5 years, with a planned 18-month follow-up period. The V-QUIN study being undertaken in Vietnam will evaluate six months of LVX vs. placebo in all contacts (adults and children) with a planned 30-month follow-up period. The PHOENix trial is a multi-site study at various household contact study sites across Africa, South America and Asia, and will compare six months of DLM vs. standard-dose INH with a planned 22-month follow-up period. It is unclear whether these trials have attempted to standardize their subgroup eligibility criteria and analysis plans to facilitate evaluation of trial results to inform future guideline development.

Both this expert group and others have emphasized that the alternative to not providing preventive therapy cannot be inaction52. Implementation of the periodic screening of MDR-TB contacts for 2 years (as recommended by the WHO) is inadequate and unmeasured, and has led to calls for national TB programs to maintain a registry of MDR-TB contacts that records interventions and 24-month outcomes52. This approach would provide valuable observational programmatic data to be evaluated alongside trial data.

Active case finding for high-risk groups and congregate settings

Efforts to scale-up treatment for active DR-TB disease and DR-TB infection in high incidence settings should be accompanied by efforts to characterize and address community transmission risks. Molecular epidemiological studies have demonstrated high rates of transmission in crowded congregate settings, including healthcare facilities53, shelters54, mines and prisons55. However, the limitations of these studies include being undertaken during outbreaks in which the source cases may not be identified with certainty, and variability in patient infectiousness and the latency period. Frequent low-intensity exposures may be responsible for a greater proportion of transmission than fewer high-intensity exposures56, 57.

TB transmission in healthcare facilities is thought to be primarily driven by patients with unsuspected (and thus untreated TB) because TB infection control (TB-IC), if implemented, focuses on patients with known and suspected TB. However, in many settings without access to rapid DST, patients with unsuspected DR-TB may be on ineffective treatment (for presumed DS-TB) and contribute to ongoing transmission58.

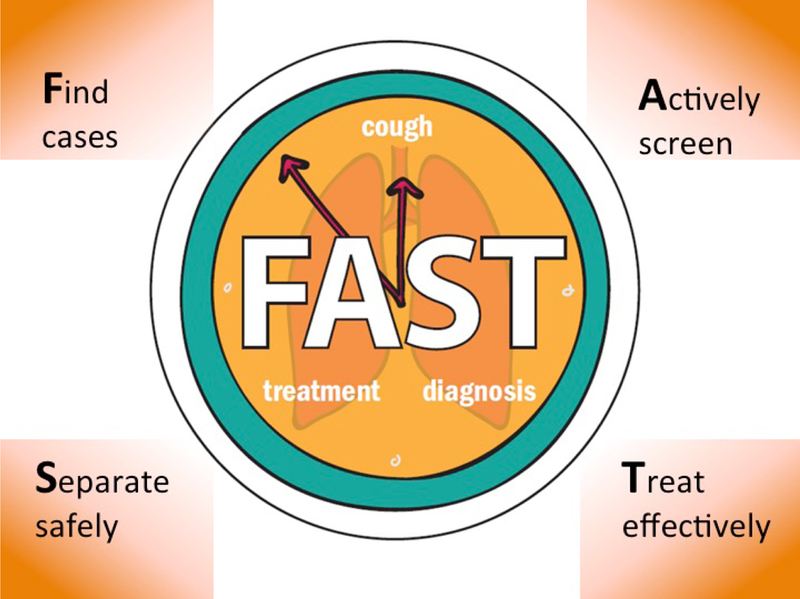

FAST (Find cases Actively, Separate safely and Treat effectively) is an intensified, refocused approach to reduce TB (including DR-TB) transmission in health-care facilities (Figure 1). FAST is based on two key principles: 1) rapid molecular tests such as Xpert or LPAs enable prompt diagnosis of TB, including DR-TB, and 2) effective treatment renders patients non-infectious well before sputum smears convert to negative58. Evaluation of FAST has revealed high rates of MDR-TB in patients with a history of previously treated TB59 that are consistent with other studies60, 61, thereby raising questions about enhanced screening and follow-up of patients with a history of previous TB.

Figure 1.

Principles of FAST.

Intense transmission of DR-TB, in prisons is well documented.62, 63 However, these congregate settings are a challenge for active case finding approaches due to the high inmate turnover, crowded living conditions and the marginalized nature of the population at risk. Evidence of the impact in reducing prison transmission through active case finding interventions has been mixed. Active case finding implemented at Dhaka Central Jail in Bangladesh led to a decline in the overall number of TB cases and clustered cases, with 2% of the isolates from this study being confirmed as MDR-TB64. In Brazilian prisons, however, large-scale active case finding using a symptom-based screen, tuberculin skin test, sputum smear microscopy and mycobacterial culture led to early detection of pulmonary TB but did not reduce the risk of subsequent disease, probably due to the force of infection65. More research on implementation of active case finding in prisons and other high-risk congregate settings, such as mines and homeless shelters, is desperately needed.

Mitigating transmission risk in patients with refractory or programmatically incurable drug-resistant TB

Treatment success rates for MDR-TB are currently around 50%, decreasing to approximately 20% for patients with XDR-TB1. Although a newer regimen consisting of BDQ, linezolid and pretomanid studied in patients with XDR-TB enrolled in the NIX-TB trial has demonstrated excellent preliminary results, with 100% culture conversion at 4 months in the 57/61 patients who survived and only one reported microbiological relapse66, there are reports of emerging resistance to the new drugs BDQ and DLM.67 It is to be hoped that the numbers of refractory or incurable DR-TB patients will diminish with improved access to DST-guided treatment provided as part of high-quality systems of care.

However, in the meantime, addressing ongoing transmission from these patients remains an important issue. Masks on patients have been shown to be approximately 50% effective in stopping transmission68. A novel approach being evaluated as a measure to reduce infectiousness and transmission from patients with incurable TB involves the administration of inhaled antibiotic treatment, such as dry-powder colistin, which is used for the treatment of multidrug-resistant organisms in patients with other structural lung diseases, such as cystic fibrosis69.

Adjunctive environmental approaches for the prevention of TB transmission focused on congregate settings

The impact of treatment on transmission relies on prompt diagnosis and treatment, but transmission occurs in indoor environments, before patients are diagnosed and can be treated. A review of WHO 2016 country data indicated that the proportion of new cases of MDR-TB in Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan were respectively 38, 26, 27, 26, 27, 22, 27, and 24%. Those data were in contrast to most of the remaining top 30 MDR-TB countries, which reported new MDR-TB cases lower than that of China (7.1%)1. These are not low-income countries nor are they settings of high HIV prevalence. However, most of these countries practice prolonged and repeated hospitalization for TB, particularly DR-TB. In addition to active case finding, using TB molecular diagnostic tools in health care facilities, as described previously,15 and shifting to predominantly ambulatory or community-based anti-TB treatment, and using environmental interventions to decrease TB (including DR-TB transmission) could be particularly important in these countries, where the cold climate limits ventilation in congregate settings, thereby amplifying transmission.

Environmental controls, such as natural ventilation or upper room germicidal ultraviolet air disinfection (GUV) could be applied as adjunctive TB-IC measures in some congregate settings, although these are typically less applicable to the household setting70. Among environmental approaches to TB transmission control, natural ventilation and upper room GUV are the most cost-effective choices71. Mechanical ventilation can be used in settings with sufficient resources but requires significant maintenance. While highly cost effective, natural ventilation depends on appropriate building design and pressure or temperature differences causing warm air to rise, and is highly reliant on local climate conditions. Ventilation estimates are typically performed (albeit, uncommonly) using labor-intensive carbon dioxide decay curves, the accuracy of which has been questioned since they are based on single measurements in time, whereas natural ventilation varies minute to minute72. For natural ventilation to remain effective, if conditions are favorable, windows should be open at night and in all seasons. However, windows are often closed for security reasons, due to cold, or to keep out vermin. In addition, in the context of global climate change, extreme temperatures are increasingly common. Natural ventilation provides little relief against extreme heat and high humidity, and is increasingly being replaced by split-system (ductless) air conditioning units, which provide cooling but no air exchange, and importantly, require a window to be closed for efficient cooling, which favors transmission of TB (or other airborne infection)73.

GUV air disinfection is among the most well-studied and cost-effective environmental interventions to reduce TB transmission72, 74. Fixtures containing germicidal lamps of wavelength 254-nm are mounted on walls or ceilings in the upper room, above the heads of occupants, and, with appropriate air mixing fans, can provide an estimated 80% reduction in TB transmission75. Wide application of GUV could be a particularly useful adjunctive TB transmission control approach in Eastern European or Central Asian countries, with little potential for natural ventilation, prolonged hospitalization, and a resulting high percentage of transmitted new MDR-TB cases.

The main challenges facing GUV involve implementation barriers that include a lack of guidelines, gaps in knowledge and necessary technical support, and ensuring high-quality, low-cost, locally produced fixtures. Additional technology innovation is being explored, for example, a combination of split-system air-conditioning units with upper room GUV air disinfection systems and use of LED UV technology. These barriers are being overcome through work in countries such as India and South Africa, funded by partners including the WHO, the End TB Transmission Initiative at the STOP TB Partnership, Centers for Control and Prevention, and the US Agency for International Development.

Conclusions

Although we focused on various aspects of transmission that are specific to DR-TB, the basic principles of transmission control remain similar for DR-TB and DS-TB. We emphasize the central importance of effective treatment as the primary means of preventing DR-TB transmission, through improved diagnosis, treatment and care of patients with both active and latent MDR-TB (Figure 2). The reduction of TB transmission, including DR-TB, is limited by gaps in our biological understanding of TB, including variability in patient infectiousness and the importance of reinfection, and our ability to identify where transmission is occurring in real-time.

Figure 2. Understanding the role of treatment as prevention to decrease MDR-TB transmission (not to scale).

Circles (not to scale) denoting treatment of active TB (combination of ACF in settings like hospitals and prisons as well as PCF) and treatment of latent TB (contacts as well as other high-risk groups) as well as adjunctive strategies to reduce transmission. MDR-TB=multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; PCF=passive case-finding; ACF=active case-finding; FAST=Find cases Actively, Separate safely and Treat effectively; DST=drug susceptibility testing; TB=tuberculosis; GUV=germicidal ultraviolet air disinfection.

However, much more can be done with existing tools. Barriers to the implementation of rapid molecular diagnostics, which include assessment for drug resistance and early initiation of effective treatment, should be overcome in both community and congregate settings, along with expansion of adjunctive proven technologies such as GUV air disinfection. Improved access to new TB drugs such as BDQ and DLM, as well as further research and development to expand the DR-TB treatment pipeline, are needed urgently to improve DR-TB treatment outcomes, thereby reducing transmission. Ultimately, robust implementation of a comprehensive package of evidence-based transmission control interventions is critical to reducing MDR-TB incidence and must be a priority at the local and global level.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The authors would like to thank Barbara Foot for editorial input.

FUNDING:

RRN, PL, DBT and EN were supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health: NIAID 1K23 AI132648 01A1 (RRN), NIAID T32 AI007061/AI (PL), NIAID 5 R01 AI112748 (DBT and EN) and NIAID 4 D43 TW009379 (RRN, DBT and EN). RRN was also supported by an ASTMH Burroughs Wellcome Fellowship.

RRN is a co-investigator for the ZeroTB Initiative, which is funded by an unrestricted grant to Harvard Medical School (PI: Keshavjee) from Janssen Global Services.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Control. WHO report; 2017. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Middlebrook G, Cohn ML. Some observations on the pathogenicity of isoniazid-resistant variants of tubercle bacilli. Science. 1953; 118(3063):297–9. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchison DA. Tubercle bacilli resistant to isoniazid; virulence and response to treatment with isoniazid in guinea-pigs. British medical journal. 1954; 1(4854):128–30. PMID: . PMCID: PMC2084405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gagneux S, Long CD, Small PM, Van T, Schoolnik GK, Bohannan BJ. The competitive cost of antibiotic resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2006; 312(5782):1944–6. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen T, Murray M. Modeling epidemics of multidrug-resistant M. tuberculosis of heterogeneous fitness. Nature medicine. 2004; 10(10):1117–21. PMID: . PMCID: PMC2652755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luciani F, Sisson SA, Jiang H, Francis AR, Tanaka MM. The epidemiological fitness cost of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009; 106(34):14711–5. PMID: . PMCID: PMC2732896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grandjean L, Gilman RH, Martin L, Soto E, Castro B, Lopez S, Coronel J, Castillo E, Alarcon V, Lopez V, San Miguel A, Quispe N, Asencios L, Dye C, Moore DA. Transmission of Multidrug-Resistant and Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis within Households: A Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS medicine. 2015; 12(6):e1001843; discussion e. PMID: . PMCID: PMC4477882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becerra MC, Appleton SC, Franke MF, Chalco K, Arteaga F, Bayona J, Murray M, Atwood SS, Mitnick CD. Tuberculosis burden in households of patients with multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011; 377(9760):147–52. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox GJ, Anh NT, Nhung NV, Loi NT, Hoa NB, Ngoc Anh LT, Cuong NK, Buu TN, Marks GB, Menzies D. Latent tuberculous infection in household contacts of multidrug-resistant and newly diagnosed tuberculosis. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2017; 21(3):297–302. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teixeira L, Perkins MD, Johnson JL, Keller R, Palaci M, do Valle Dettoni V, Canedo Rocha LM, Debanne S, Talbot E, Dietze R. Infection and disease among household contacts of patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2001; 5(4):321–8. PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uplekar M, Weil D, Lonnroth K, Jaramillo E, Lienhardt C, Dias HM, Falzon D, Floyd K, Gargioni G, Getahun H, Gilpin C, Glaziou P, Grzemska M, Mirzayev F, Nakatani H, Raviglione M, for WsGTBP. WHO’s new end TB strategy. Lancet. 2015; 385(9979):1799–801. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah NS, Auld SC, Brust JC, Mathema B, Ismail N, Moodley P, Mlisana K, Allana S, Campbell A, Mthiyane T, Morris N, Mpangase P, van der Meulen H, Omar SV, Brown TS, Narechania A, Shaskina E, Kapwata T, Kreiswirth B, Gandhi NR. Transmission of Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in South Africa. The New England journal of medicine. 2017; 376(3):243–53. PMID: . PMCID: PMC5330208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang C, Luo T, Shen X, Wu J, Gan M, Xu P, Wu Z, Lin S, Tian J, Liu Q, Yuan Z, Mei J, DeRiemer K, Gao Q. Transmission of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Shanghai, China: a retrospective observational study using whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological investigation. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2017; 17(3):275–84. PMID: . PMCID: PMC5330813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen G, Xue Z, Shen X, Sun B, Gui X, Shen M, Mei J, Gao Q. The study recurrent tuberculosis and exogenous reinfection, Shanghai, China. Emerging infectious diseases. 2006; 12(11):1776–8. PMID: . PMCID: PMC3372325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller AC LV, Khan FA, Atwood S, Kornienko S, Kononenko Y, Vasilyeva I, Keshavjee S. Turning off the tap: Using the FAST approach to stop the spread of drug-resistant tuberculosis in Russian Federation. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2018; Accepted manuscript, 10.1093/infdis/jiy190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. The use of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis TB. Meeting Report GS. [Google Scholar]

- 17.MSF. Out of Step: TB policies in 29 countries rE.

- 18.Albert H, Nathavitharana RR, Isaacs C, Pai M, Denkinger CM, Boehme CC. Development, roll-out and impact of Xpert MTB/RIF for tuberculosis: what lessons have we learnt and how can we do better? The European respiratory journal. 2016; 48(2):516–25. PMID: . PMCID: PMC4967565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clouse K, Blevins M, Lindegren ML, Yotebieng M, Nguyen DT, Omondi A, Michael D, Zannou DM, Carriquiry G, Pettit A, International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate Ac. Low implementation of Xpert MTB/RIF among HIV/TB co-infected adults in the International epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) program. PloS one. 2017; 12(2):e0171384. PMID: . PMCID: PMC5300213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson KR, Barnard M, Kleinman MB, Streicher EM, Ragan EJ, White LF, Shapira O, Dolby T, Simpson J, Scott L, Stevens W, van Helden PD, Van Rie A, Warren RM. Implications of Failure to Routinely Diagnose Resistance to Second-Line Drugs in Patients With Rifampicin-Resistant Tuberculosis on Xpert MTB/RIF: A Multisite Observational Study. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017; 64(11):1502–8. PMID: . PMCID: PMC5434334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nathavitharana RR, Cudahy PG, Schumacher SG, Steingart KR, Pai M, Denkinger CM. Accuracy of line probe assays for the diagnosis of pulmonary and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The European respiratory journal. 2017; 49(1). PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore DA, Evans CA, Gilman RH, Caviedes L, Coronel J, Vivar A, Sanchez E, Pinedo Y, Saravia JC, Salazar C, Oberhelman R, Hollm-Delgado MG, LaChira D, Escombe AR, Friedland JS. Microscopic-observation drug-susceptibility assay for the diagnosis of TB. The New England journal of medicine. 2006; 355(15):1539–50. PMID: . PMCID: PMC1780278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie YL, Chakravorty S, Armstrong DT, Hall SL, Via LE, Song T, Yuan X, Mo X, Zhu H, Xu P, Gao Q, Lee M, Lee J, Smith LE, Chen RY, Joh JS, Cho Y, Liu X, Ruan X, Liang L, Dharan N, Cho SN, Barry CE 3rd, Ellner JJ, Dorman SE, Alland D. Evaluation of a Rapid Molecular Drug-Susceptibility Test for Tuberculosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2017; 377(11):1043–54. PMID: . PMCID: PMC5727572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pankhurst LJ, Del Ojo Elias C, Votintseva AA, Walker TM, Cole K, Davies J, Fermont JM, Gascoyne-Binzi DM, Kohl TA, Kong C, Lemaitre N, Niemann S, Paul J, Rogers TR, Roycroft E, Smith EG, Supply P, Tang P, Wilcox MH, Wordsworth S, Wyllie D, Xu L, Crook DW, Group C-TS. Rapid, comprehensive, and affordable mycobacterial diagnosis with whole-genome sequencing: a prospective study. The Lancet Respiratory medicine. 2016; 4(1):49–58. PMID: . PMCID: PMC4698465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riley RL, Mills CC, Nyka W, Weinstock N, Storey PB, Sultan LU, Riley MC, Wells WF. Aerial dissemination of pulmonary tuberculosis. A two-year study of contagion in a tuberculosis ward. 1959. American journal of epidemiology. 1995; 142(1):3–14. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riley RL, Mills CC, O’Grady F, Sultan LU, Wittstadt F, Shivpuri DN. Infectiousness of air from a tuberculosis ward. Ultraviolet irradiation of infected air: comparative infectiousness of different patients. The American review of respiratory disease. 1962; 85:511–25. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dharmadhikari AS, Mphahlele M, Venter K, Stoltz A, Mathebula R, Masotla T, van der Walt M, Pagano M, Jensen P, Nardell E. Rapid impact of effective treatment on transmission of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2014; 18(9):1019–25. PMID: . PMCID: PMC4692272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gelmanova IY, Keshavjee S, Golubchikova VT, Berezina VI, Strelis AK, Yanova GV, Atwood S, Murray M. Barriers to successful tuberculosis treatment in Tomsk, Russian Federation: non-adherence, default and the acquisition of multidrug resistance. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2007; 85(9):703–11. PMID: . PMCID: PMC2636414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kendall EA, Azman AS, Cobelens FG, Dowdy DW. MDR-TB treatment as prevention: The projected population-level impact of expanded treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. PloS one. 2017; 12(3):e0172748. PMID: . PMCID: PMC5342197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bastard M, Guglielmetti L, Huerga H, Hayrapetyan A, Khachatryan N, Yegiazaryan L, Faqirzai J, Hovhannisyan L, Varaine F, Hewison C. Bedaquiline and Repurposed Drugs for Fluoroquinolone-Resistant MDR-TB: How Much Better Are They? American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2018. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pontali E, Sotgiu G, Tiberi S, Tadolini M, Visca D, D’Ambrosio L, Centis R, Spanevello A, Migliori GB. Combined treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis with bedaquiline and delamanid: a systematic review. The European respiratory journal. 2018; 52(1). PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnippel K, Ndjeka N, Maartens G, Meintjes G, Master I, Ismail N, Hughes J, Ferreira H, Padanilam X, Romero R, Te Riele J, Conradie F. Effect of bedaquiline on mortality in South African patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Respiratory medicine. 2018. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hewison C, Bastard M, Khachatryan N, Kotrikadze T, Hayrapetyan A, Avaliani Z, Kiria N, Yegiazaryan L, Chumburidze N, Kirakosyan O, Atshemyan H, Qayyum S, Lachenal N, Varaine F, Huerga H. Is 6 months of bedaquiline enough? Results from the compassionate use of bedaquiline in Armenia and Georgia. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2018; 22(7):766–72. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02409290ITEoaSTRoA-tDfPWM-TS.

- 35.Holtz TH, Sternberg M, Kammerer S, Laserson KF, Riekstina V, Zarovska E, Skripconoka V, Wells CD, Leimane V. Time to sputum culture conversion in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: predictors and relationship to treatment outcome. Annals of internal medicine. 2006; 144(9):650–9. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prideaux B, Via LE, Zimmerman MD, Eum S, Sarathy J, O’Brien P, Chen C, Kaya F, Weiner DM, Chen PY, Song T, Lee M, Shim TS, Cho JS, Kim W, Cho SN, Olivier KN, Barry CE 3rd, Dartois V. The association between sterilizing activity and drug distribution into tuberculosis lesions. Nature medicine. 2015; 21(10):1223–7. PMID: . PMCID: PMC4598290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kempker RR, Vashakidze S, Solomonia N, Dzidzikashvili N, Blumberg HM. Surgical treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2012; 12(2):157–66. PMID: . PMCID: PMC3741680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lalloo UG, Naidoo R, Ambaram A. Recent advances in the medical and surgical treatment of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2006; 12(3):179–85. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pomerantz BJ, Cleveland JC Jr., Olson HK, Pomerantz M. Pulmonary resection for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2001; 121(3):448–53. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Somocurcio JG, Sotomayor A, Shin S, Portilla S, Valcarcel M, Guerra D, Furin J. Surgery for patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis: report of 121 cases receiving community-based treatment in Lima, Peru. Thorax. 2007; 62(5):416–21. PMID: . PMCID: PMC2117182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sung SW, Kang CH, Kim YT, Han SK, Shim YS, Kim JH. Surgery increased the chance of cure in multi-drug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 1999; 16(2):187–93. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris RC, Khan MS, Martin LJ, Allen V, Moore DA, Fielding K, Grandjean L, group LM-Tssr. The effect of surgery on the outcome of treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC infectious diseases. 2016; 16:262 PMID: . PMCID: PMC4901410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marrone MT, Venkataramanan V, Goodman M, Hill AC, Jereb JA, Mase SR. Surgical interventions for drug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2013; 17(1):6–16. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Calligaro GL, Moodley L, Symons G, Dheda K. The medical and surgical treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Journal of thoracic disease. 2014; 6(3):186–95. PMID: . PMCID: PMC3949182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teo DT, Lim TW. Transmission of tuberculosis from patient to healthcare workers in the anaesthesia context. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 2004; 33(1):95–9. PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yates TA, Khan PY, Knight GM, Taylor JG, McHugh TD, Lipman M, White RG, Cohen T, Cobelens FG, Wood R, Moore DA, Abubakar I. The transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in high burden settings. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2016; 16(2):227–38. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sreeramareddy CT, Panduru KV, Menten J, Van den Ende J. Time delays in diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review of literature. BMC infectious diseases. 2009; 9:91 PMID: . PMCID: PMC2702369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smieja MJ, Marchetti CA, Cook DJ, Smaill FM. Isoniazid for preventing tuberculosis in non-HIV infected persons. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2000(2):CD001363. PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Latent tuberculosis infection: updated and consolidated guidelines for programmatic management. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Global consultation on best practices in the delivery of preventive therapy for household contacts of patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis Proceedings of the Harvard Medical School Center for Global Health Delivery–Dubai. 2015, Vol. 1, No. 1. Dubai, United Arab Emirates: Harvard Medical School Center for Global Health Delivery–Dubai. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marks SM, Mase SR, Morris SB. Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Cost-effectiveness of Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis to Reduce Progression to Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017; 64(12):1670–7. PMID: . PMCID: PMC5543758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore DA. What can we offer to 3 million MDRTB household contacts in 2016? BMC medicine. 2016; 14:64 PMID: . PMCID: PMC4818855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gandhi NR, Weissman D, Moodley P, Ramathal M, Elson I, Kreiswirth BN, Mathema B, Shashkina E, Rothenberg R, Moll AP, Friedland G, Sturm AW, Shah NS. Nosocomial transmission of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in a rural hospital in South Africa. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013; 207(1):9–17. PMID: . PMCID: PMC3523793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nardell E, McInnis B, Thomas B, Weidhaas S. Exogenous reinfection with tuberculosis in a shelter for the homeless. The New England journal of medicine. 1986; 315(25):1570–5. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Urrego J, Ko AI, da Silva Santos Carbone A, Paiao DS, Sgarbi RV, Yeckel CW, Andrews JR, Croda J. The Impact of Ventilation and Early Diagnosis on Tuberculosis Transmission in Brazilian Prisons. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2015; 93(4):739–46. PMID: . PMCID: PMC4596592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mathema B, Andrews JR, Cohen T, Borgdorff MW, Behr M, Glynn JR, Rustomjee R, Silk BJ, Wood R. Drivers of Tuberculosis Transmission. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2017; 216(suppl_6):S644–S53. PMID: . PMCID: PMC5853844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rose G Sick individuals and sick populations. International journal of epidemiology. 1985; 14(1):32–8. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barrera E, Livchits V, Nardell E. F-A-S-T: a refocused, intensified, administrative tuberculosis transmission control strategy. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2015; 19(4):381–4. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nathavitharana RR, Daru P, Barrera AE, Mostofa Kamal SM, Islam S, Ul-Alam M, Sultana R, Rahman M, Hossain MS, Lederer P, Hurwitz S, Chakraborty K, Kak N, Tierney DB, Nardell E. FAST implementation in Bangladesh: high frequency of unsuspected tuberculosis justifies challenges of scale-up. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2017; 21(9):1020–5. PMID: . PMCID: PMC5757242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marx FM, Dunbar R, Enarson DA, Williams BG, Warren RM, van der Spuy GD, van Helden PD, Beyers N. The temporal dynamics of relapse and reinfection tuberculosis after successful treatment: a retrospective cohort study. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2014; 58(12):1676–83. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marx FM, Floyd S, Ayles H, Godfrey-Faussett P, Beyers N, Cohen T. High burden of prevalent tuberculosis among previously treated people in Southern Africa suggests potential for targeted control interventions. The European respiratory journal. 2016; 48(4):1227–30. PMID: . PMCID: PMC5512114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chaves F, Dronda F, Cave MD, Alonso-Sanz M, Gonzalez-Lopez A, Eisenach KD, Ortega A, Lopez-Cubero L, Fernandez-Martin I, Catalan S, Bates JH. A longitudinal study of transmission of tuberculosis in a large prison population. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1997; 155(2):719–25. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reis AJ, David SM, Nunes LS, Valim AR, Possuelo LG. Recent transmission of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a prison population in southern Brazil. Jornal brasileiro de pneumologia : publicacao oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisilogia. 2016; 42(4):286–9. PMID: . PMCID: PMC5063446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Banu S, Rahman MT, Uddin MK, Khatun R, Khan MS, Rahman MM, Uddin SI, Ahmed T, Heffelfinger JD. Effect of active case finding on prevalence and transmission of pulmonary tuberculosis in Dhaka Central Jail, Bangladesh. PloS one. 2015; 10(5):e0124976. PMID: . PMCID: PMC4416744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Paiao DS, Lemos EF, Carbone AD, Sgarbi RV, Junior AL, da Silva FM, Brandao LM, Dos Santos LS, Martins VS, Simionatto S, Motta-Castro AR, Pompilio MA, Urrego J, Ko AI, Andrews JR, Croda J. Impact of mass-screening on tuberculosis incidence in a prospective cohort of Brazilian prisoners. BMC infectious diseases. 2016; 16(1):533 PMID: . PMCID: PMC5048439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Conradie F DA, Everitt D, Mendel C, van Niekerk C, Howell P, Comins K, Spigelman M. The NIX-TB trial of pretomanid, bedaquiline and linezolid to treat XDR-TB Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2017), Seattle, abstract 80LB, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bloemberg GV, Keller PM, Stucki D, Trauner A, Borrell S, Latshang T, Coscolla M, Rothe T, Homke R, Ritter C, Feldmann J, Schulthess B, Gagneux S, Bottger EC. Acquired Resistance to Bedaquiline and Delamanid in Therapy for Tuberculosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2015; 373(20):1986–8. PMID: . PMCID: PMC4681277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dharmadhikari AS, Mphahlele M, Stoltz A, Venter K, Mathebula R, Masotla T, Lubbe W, Pagano M, First M, Jensen PA, van der Walt M, Nardell EA. Surgical face masks worn by patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: impact on infectivity of air on a hospital ward. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012; 185(10):1104–9. PMID: . PMCID: PMC3359891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Breda SV, Buys A, Apostolides Z, Nardell EA, Stoltz AC. The antimicrobial effect of colistin methanesulfonate on Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vitro. Tuberculosis. 2015; 95(4):440–6. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nardell EA. Indoor environmental control of tuberculosis and other airborne infections. Indoor air. 2016; 26(1):79–87. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bloom BR AR, Cohen T, et al. Tuberculosis. In: Disease Control Priorities, Third, https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-EVMID,6.pdf.cusD-C-P-T-E-V-, Accessed December 15. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nardell EA. Transmission and Institutional Infection Control of Tuberculosis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2015; 6(2):a018192. PMID: . PMCID: PMC4743075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lederer P, Nardell EA. Cool but Dangerous . Manuscript in submission. [Google Scholar]

- 74.First M, Rudnick SN, Banahan KF, Vincent RL, Brickner PW. Fundamental factors affecting upper-room ultraviolet germicidal irradiation - part I. Experimental. Journal of occupational and environmental hygiene. 2007; 4(5):321–31. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mphaphlele M, Dharmadhikari AS, Jensen PA, Rudnick SN, van Reenen TH, Pagano MA, Leuschner W, Sears TA, Milonova SP, van der Walt M, Stoltz AC, Weyer K, Nardell EA. Institutional Tuberculosis Transmission. Controlled Trial of Upper Room Ultraviolet Air Disinfection: A Basis for New Dosing Guidelines. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2015; 192(4):477–84. PMID: . PMCID: PMC4595666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]