Abstract

The objective of this research was to find the possible pharmacognosy of the bark of the Philippine Alstonia macrophylla Wall. ex G.Don (AM). Gas chromatographic–mass spectral (GC–EI-MS) characterization and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) were performed to detect the bioactive constituents. EDX analysis of AM bark displayed a high content of potassium (3.26%) and calcium (2.96%). Eight constituents were detected in AM crude dichloromethane (DCM) extracts, which consisted of a long-chain unsaturated fatty acid (17:0) and fatty acid esters such as ethyl hexadecanoate and methyl hexadecanoate. Extraction of AM bark using methanol and dimethyl sulfoxide (MeOH/DMSO) solvents resulted in the identification of 17 constituents, principally alkaloids (alstonerine, 34.38%; strictamin, 5.23%; rauvomitin, 4.29%; and brucine, 3.66%) and triterpenoids (γ-sitosterol, 3.85%; lupeol, 3.00%; 24-methylenecycloartanol, 2.81%; campesterol, 2.71%; β-amyrin, 2.30%; and stigmasterol, 2.13%). MeOH/DMSO samples of AM were used in the selected bioassays. The samples exhibited efficient free radical scavenging activity (IC50 = 0.71 mg/mL) and were noncytotoxic to normal HDFn (IC50 > 100 μg/mL) and neoplastic THP-1 cell lines (IC50 = 67.22 μg/mL) while highly degenerative to MCF-7 (IC50 = 6.34 μg/mL), H69PR (IC50 = 7.05 μg/mL), and HT-29 (IC50 = 9.10 μg/mL). Most interestingly, the AM samples inhibited the northern Philippine Cobra’s (Naja philippinensis Taylor) venom (IC50 = 297.27 ± 9.33 μg/mL) through a secretory phospholipase A2 assay.

1. Introduction

Medicinal plants are still widely used in nonindustrialized societies such as in many parts of Southeast Asia because they are readily available and cheaper than modern medicines. In the Philippines, some of the most important and highly recognized medicinal plants belong to genus Alstonia in the family Apocynaceae. Two of its five Philippine native species, Alstonia macrophylla Wall. ex G.Don and Alstonia scholaris (L.) R. Br., are locally important, and various organs of these plants are harvested as natural remedies for human ailments.

Both A. macrophylla and A. scholaris were reported to contain echitovenidine, echitamine, venenatine (an indole alkaloid), and anti-inflammatory triterpenoids.1−5 The bark of the A. scholaris, the most intensively used organ of this species, was recently found to have strong antifungal activity.6 It was also found to relieve anxiety- and stress-related incidences through stabilization of distress-induced physiological deviations seen in mice plasma.7,8

In its powdered form, the bark of A. macrophylla (AM), also known as hard milkwood or batino, is used in wine preparation and as an antipyretic, traditional remedy and preventive concoction, medicine for dysentery, an aid in the menstrual cycle, treatment in Alzheimer’s disease through down regulation of acetylcholine, and in wound healing.9−11 When mixed with water, the powdered bark can be used as an astringent and for treating skin diseases.12 Apart from the bark, crushed leaves of AM, when mixed with copra oil and warmed, were applied as heated dressings to joint and muscle injuries.13 Moreover, decoctions of its undeveloped aerial plant parts were ingested as a curative for respiratory and auditory obstructions.14 Mixed preparations of leaves and stem bark of AM were used in the Republic of India to treat upset stomachs, dermal conditions, and bacterial infections of the urinary tract.12,15 Similar to A. scholaris, AM leaves extracted with methanol similarly exhibited antimicrobial properties.16

A variety of phytochemical analytes have been reported from distinct organs of AM. Phytochemical investigations of AM afforded steroid alcohols, isoprenoids, hydroxylated polyphenolic compounds, alkaloids, tannic acids, and monosaccharides. AM was found to be rich in β-sitosterol, a phytosterol that is an effective inhibitor of semen movability, and has possible use as a family planning medicine for women.17 A study of the aerial parts reported 19 alkaloidal compounds, 15 of which were elucidated. In another study, also using leaf extracts yielded 10 undiscovered indole alkaloids, alstomaline, 10,11-dimethoxynareline, alstohentine, alstomicine, 16-hydroxyalstonisine, 16-hydroxyalstonal, 16-hydroxy-N4-demethylalstophyllal oxindole, alstophyllal, 6-oxoalstophylline, and 6-oxoalstophyllal, in consort with 21 others already discovered by a previous study.9 Like A. scholaris, AM also has abundant alkaloids. To date, nearly 70 dissimilar categories of alkaloid derivatives have been described in various organs of AM, and a majority of them were isolated from the stem bark.18

In this work, we established the antioxidant (by a modified assay using 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH)), cytotoxic (HT-29, H69PR, MCF-7, THP-1 immortalized cell lines, and normal HDFn primary culture cells), and antivenom activities of crude AM extracts. Chemical characterization was achieved utilizing gas chromatography in tandem with mass spectrometry and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. After our thorough investigation, we believe that this original work is the first to describe the research of these selected bioassay experiments of crude AM extracts using a MeOH/DMSO solvent extraction protocol of A. macrophylla bark.

2. Results and Discussion

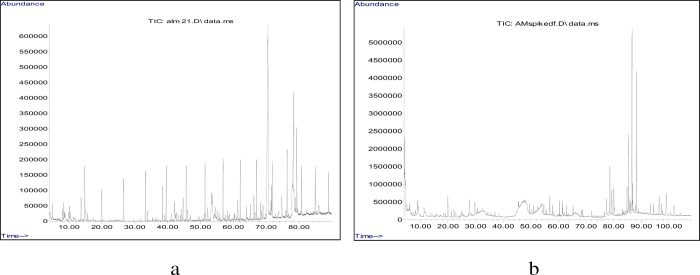

2.1. GC–EI-MS Assessments of AM

Gas chromatographic–mass spectral examinations of the DCM preparations of AM detected the presence of eight analytes. The verified volatile constituents of the reaction mixture were confirmed through retention index (RI) and structural category via the NIST Archive. In Table 1, the findings are enumerated corresponding to peak succession visualization on an HP-5 ms column. The sample, seen in Table 1 and Figure 1, consisted chiefly of a fatty acid and fatty acid esters: heptadecanoic acid (16.61%); hexadecanoic acid ethyl ester (12.21%); and hexadecanonic acid methyl ester (10.46%).

Table 1. Volatile Constituents of DCM Extracts of AM.

| compound | RT (min) | RIa | % peak area | functionality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-ethenyl-2-butenal | 8.07 | 890 | 6.17 | aldehyde |

| 3-ethylpyridine | 11.38 | 956 | 1.21 | diverse functional group |

| nonanoic acid | 31.72 | 1277 | 0.92 | carboxylic acid |

| cyclohexylbenzene | 33.81 | 1309 | 4.96 | hydrocarbon |

| 3-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzyl alcohol | 42.38 | 1445 | 8.41 | alcohol |

| hexadecanonic acid methyl ester | 68.37 | 1927 | 10.46 | ester |

| hexadecanoic acid ethyl ester | 71.40 | 1990 | 12.21 | ester |

| heptadecanoic acid | 74.80 | 2065 | 16.61 | carboxylic acid |

Retention index (HP-5 ms column).

Figure 1.

Total ion GC–MS chromatogram of (a) DCM and (b) MeOH/DMSO extract of AM with n-alkanes.

The MEOH/DMSO crude AM extracts were composed primarily of alkaloids (Table 2 and Figure 1): alstonerine (34.38%), strictamin (5.23%), rauvomitin (4.29%), and brucine (3.66%). Other notable constituents from this polar extract were triterpenoids: γ-sitosterol (3.85%), lupeol (3.00%), 24-methylenecycloartanol (2.81%), campesterol (2.71%), β-amyrin (2.30%), and stigmasterol (2.13%). Since more bioactive phytochemicals were found in the MEOH/DMSO crude AM extracts, extracts using this solvent extraction technique were used in all the subsequent bioassays.

Table 2. Volatile Constituents of MeOH:DMSO Extracts of AM.

| compound | RT (min) | RIa | % peak area | functionality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,5-dimethyl-4-hydroxy-3(2H)-furanone | 7.20 | 1026 | 1.16 | trihydroxybenzene |

| 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol | 19.96 | 1355 | 5.37 | diterpenoid |

| 2,6-dimethoxyphenol | 22.13 | 1375 | 1.83 | diverse functional group |

| 2,6-dimethoxy-4-(2-propenyl)-phenol | 45.43 | 1660 | 3.69 | diverse functional group |

| 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid | 49.60 | 1690 | 1.66 | phenolic acid |

| strictamin | 77.42 | 2519 | 5.23 | alkaloid |

| rauvomitin | 84.82 | 2522 | 4.29 | alkaloid |

| alstonerine | 86.66 | 2544 | 34.38 | alkaloid |

| brucine | 86.85 | 2545 | 3.66 | alkaloid |

| burnamicine | 87.94 | 2561 | 1.71 | alkaloid |

| campesterol | 93.35 | 2643 | 2.71 | triterpenoid |

| stigmasterol | 94.44 | 2663 | 2.13 | triterpenoid |

| γ-sitosterol | 96.48 | 2701 | 3.85 | triterpenoid |

| β-amyrin | 97.27 | 2716 | 2.30 | triterpenoid |

| lupeol | 98.43 | 2738 | 3.00 | triterpenoid |

| 24-methylenecycloartanol | 101.84 | 2802 | 2.81 | triterpenoid |

Retention index (HP-5 ms column).

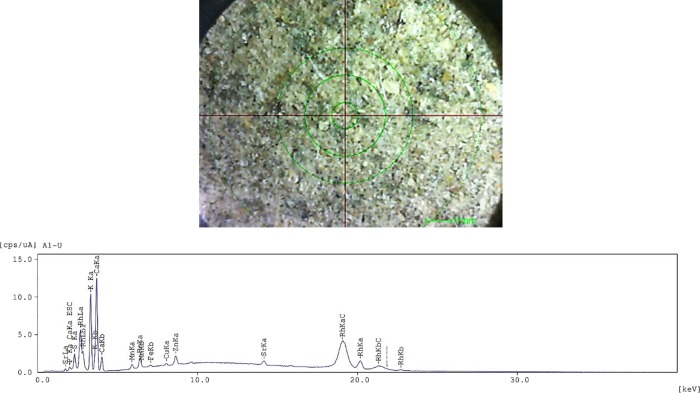

2.2. EDX Analysis of AM

The chemical compositions of the adsorbents were found to have an elemental percentage (<ppm) of K (3.26%), Ca (2.96%), Cl (0.93%), S (0.60%), Si (0.47%), P (0.30%), Fe (0.05%), Mn (0.03%), and Zn (0.04%) with glucose, C6H10O5, making up 91.36%. Elevated percentages of potassium (K) and calcium (Ca) suggest that the plant metabolized high consumption of mineral nutrients absorbed from the soil of the sample as demonstrated in Figure 2. Assessments linking calcium ingestion in healthy elderly women were determined to ameliorate lipid panels, sugar metabolic rate, and normalization of hypertension.21,22 The increase in the consumption of potassium-rich foods has been well established to regulate cardiovascular anomalies, alleviate orthopedic and renal diseases, and prevent strokes.23

Figure 2.

EDX image (top) and X-ray energy spectrum (bottom) of AM bark.

Other genera from the Apocynaceae family were subjected to EDX analyses. The pulverized aerial material and nodal and internodal bark powder (2.0 g) of Grewia lasiocarpa E.Mey. ex Harv. underwent elemental analyses using an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDX), connected to software operated by the Aztec system from Oxford Instruments (U.K.). Twenty-two elements were found present, of which three foremost essential elements were obtained [sodium (Na), sulfur (S), and calcium (Ca)]. Fifteen residual metals [chromium (Cr), manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), cobalt (Co), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), magnesium (Mg), iodine (I), potassium (K), molybdenum (Mo), silicon (Si), nickel (Ni), tin (Sn), selenium (Se), and vanadium (V)] and five transition elements [arsenic (As), mercury (Hg), rubidium (Rb), cadmium (Cd), and lead (Pb)] were present.24

Elemental investigations performed on powdered leaves, stems, and roots of Ichnocarpus frutescens wherein copper sample remnants were prepared pursuant to coating with a gold sputter coater. Elemental analyses were restricted to eleven elements (C, O, Mg, Al, Si, Cl, K, Ca, Fe, Cu, and Zn). The mineral content for the roots displayed the presence of all the specified elements; however, the leaves were deficient in iron and aluminum, and the stem was deficient in magnesium.25

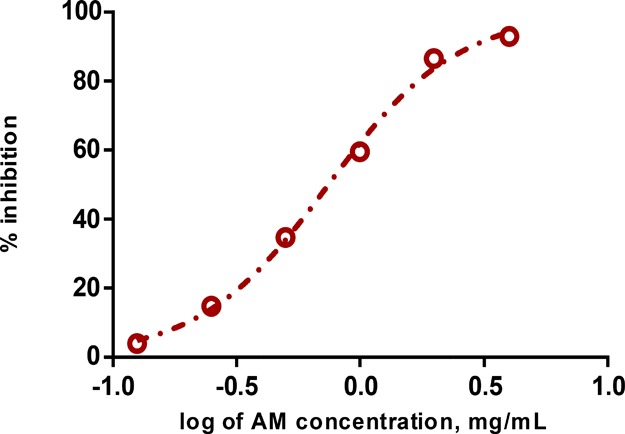

2.3. Antioxidant Activity of AM

AM crude extracts were found to be effective free radical scavengers given that the IC50 value was low at 0.71 mg/mL (Figure 3). A previous report showed that three chief constituents purified from the methanolic fraction of A. macrophylla leaf, specifically β-sitosterol, ursolic acid, and β-sitosteryl-β-d-glucoside, as well as a minor fraction found to have alkaloid and fatty acids were the entities that induced antioxidant activity at an effective concentration of 200 mg/kg (DPPH protocol evaluations, superoxide anion quenching experiments, and DNA cleavage assay).17

Figure 3.

Free radical scavenging analyses of AM.

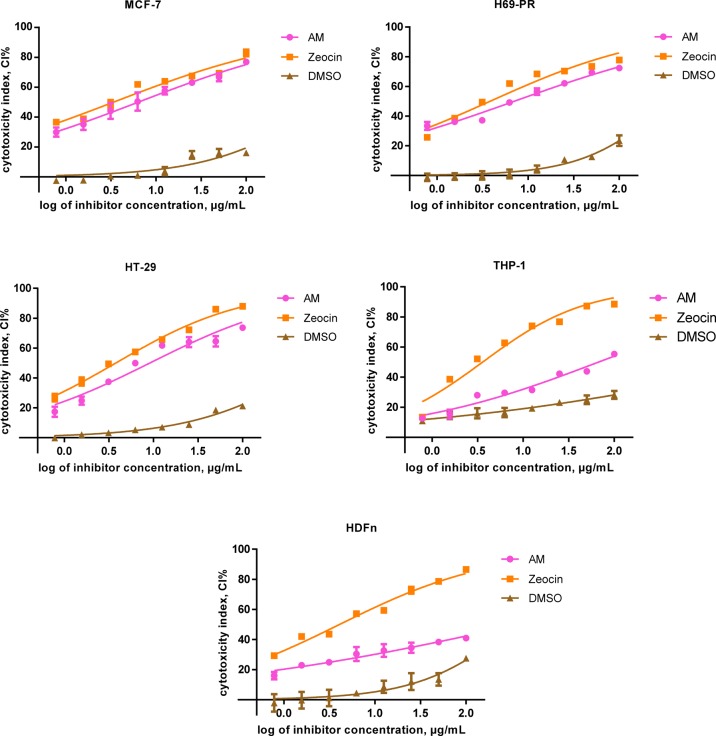

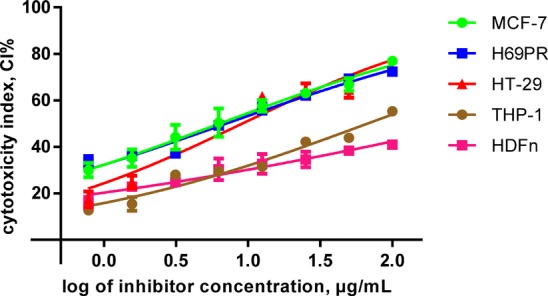

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assays

The cytotoxicity of the crude extract of AM was investigated on MCF-7, H69PR, HT-29, THP-1 immortalized cell lines, and normal HDFn primary culture cells. Analyses of the cytotoxicity of AM done on normal HDFn resulted in IC50 values exceeding 100 μg/mL. Zeocin, a DNA intercalating agent, was used as the positive control in all the trials. An illustration of the percent of intact live cells as a correlation to the inverse function to exponentiation of the concentrations used can be found in Figures 4 and 5. The characteristic inhibitory dose–response, which is a sigmoidal curve or function, was found in generally most of the charts. Plots comparing the cytotoxic properties of AM and Zeocin on the viability of each specific cell line are found in Figure 4. IC50 values of the isolates and the positive control are synopsized in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Cytotoxic activities of AM, Zeocin, and DMSO on the cytotoxicity index (CI%) of immortalized cell lines (dose–response curves with data points as mean ± SEM). GraphPad Prism 7.01 (GraphPad Software, Inc., USA) was employed for extra sum-of-squares F test calculations to (A) appraise the implication of the best-fit-parameter (half maximal inhibitory concentration) between selected trials and to (B) assess the variances amid the dose–response curve fits. MCF-7 F (Dfn, DFd) = (A) F (2, 48) = 3192, p < 0.0001 and (B) F (2, 21) = 34.37, p < 0.0001; H69PR (A) F (2, 48) = 5205, p < 0.0001and (B) F (2, 21) = 29.45, p < 0.0001; HT-29 (A) F (2, 46) = 4892, p < 0.0001 and (B) F (2, 21) = 18.81, p < 0.0001; THP-1 (A) F (2, 48) = 3511, p < 0.0001 and (B) F (2, 21) = 12.41, p = 0.0003; HDFn (A) F (2, 48) = 1577, p < 0.0001 and (B) F (2, 21) = 27.70, p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

Cytotoxic activities of AM based on the CI% of the immortalized cell lines. Graphs show the result of AM on individual cell lines. Dose–response curves were formed from data points as mean ± SEM. The GraphPad Prism 7.01 software was applied to perform the extra sum-of-squares F test to (A) gauge the implication of the best-fit-parameter of IC50 values between separate treatments and to (B) ascertain the variances amid the dose–response curve congruency. AM, (A) F (4, 80) = 445.2, p < 0.0001 (B) F (4, 35) = 4.176, p = 0.0072.

Table 3. Cytotoxic Activities (IC50) of the AM Crude Extract and Zeocin against Cell Lines.

| IC50a (μg/mL) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample | MCF-7 | H69PR | HT-29 | THP-1 | HDFn |

| AM | 6.34 | 7.05 | 9.10 | 67.22 | >100 |

| Zeocin | 3.37 | 3.83 | 3.78 | 3.59 | 4.08 |

IC50 data were deduced from dose–response graphs extrapolated from nonlinear regression analysis by means of GraphPad Prism 7.01 The unpaired two-tailed t test was the treatment employed for each cell line to evaluate the significant variances among the data groups. The statistical data were as follows: MCF-7, t (14) = 0.7047, p = 0.4925; H69PR, t (14) = 0.7285, p = 0.4783; HT-29, t (14) = 1.056, p = 0.3090; THP-1, t (14) = 2.798, p = 0.0142; HDFn, t (14) = 3.761, p = 0.0021.

Crude extracts of AM gave the highest cytotoxic efficacy toward MCF-7 with a half maximal inhibitory concentration of 6.34 μg/mL, which was followed by H69PR, HT-29, and THP-1 with IC50 values of 7.05, 9.10, and 67.22 μg/mL, respectively. Significant differences for the degree of potency, as found in Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparison, were found between almost all cell lines (p < 0.05) except for the paired treatment of MCF-7 versus H69PR, which was displayed to be statistically similar (p > 0.05). Data subsets of aforementioned cancer cell lines and Zeocin exhibited that the paired treatments were comparable (p > 0.05).

There were no perceivable variances as found in the unpaired t test between the paired trials of AM versus Zeocin (p > 0.05) in MCF-7 trials. In fact, there was no significant difference in the scores for mean values of AM (M = 53.02, SD = 5.71) and mean values for Zeocin (M = 58.69, SD = 5.67) conditions; t (14) = 0.7047, p = 0.4925. These results exhibited that the antiproliferative actions of both AM and Zeocin were comparable.

Trials using H69PR showed that the AM cytotoxic activity was comparable to Zeocin displaying no significant differences between the two inhibitors (p > 0.05) as found through an independent sample t test comparison. Results for the unpaired t test exhibited the mean values of AM (M = 52.02, SD = 5.44) and mean values for Zeocin (M = 58.22, SD = 6.54) conditions (t (14) = 0.7285, p = 0.4783).

Post hoc analysis revealed that there were no significant differences between the paired treatments (p > 0.05) of HT-29 of AM and Zeocin. The mean IC50 values of HT-29 cells treated with AM (M = 49.16, SD = 7.27) and mean IC50 values of HT-29 cells treated with Zeocin (M = 60.38, SD = 7.75) were found not to have significant variance (t(14) = 1.056, p = 0.3090).

The global or shared results of THP-1 with inhibitor trials reject the null hypothesis and exemplifies that both data subsets are unique (p < 0.05). Significant differences were seen between the two inhibitors (p < 0.05), and the results for the unpaired t test disclosed the values of AM (M = 32.31, SD = 5.10) and for Zeocin (M = 61.67, SD = 9.17) conditions (t (14) = 2.798, p = 0.0142).

AM was established to be noncytotoxic to normal HDFn, with an IC50 value substantially surpassing concentrations of 100 μg/mL. Multiple comparisons of AM and immortalized cell line examinations confirmed that there were significant differences and, the null hypothesis (one curve for all datasets) was rejected (log IC50 the same for all datasets) as verified by the goodness of fit of the two alternative nested models (IC50) between separate experiments, F (4, 80) = 445.2, p < 0.0001, and to the discrepancies amid the dose–response diagrams F (4, 35) = 4.176, p = 0.0072. Similarly, pertaining to their respective IC50 results, trials with aberrant cell lines treated with Zeocin were found to not be significantly disparate (p > 0.05). Zeocin, a known cytotoxic agent, gave IC50 values of 3.37, 3.83, 3.78, 3.59, and 4.08 ppm in MCF-7, H69PR, HT-29, THP-1, and HDFn, respectively. Multiple comparisons showed negative noteworthy variances in the trials (p > 0.05). Post hoc comparison of the dose–response curve fits for the aberrant cell line treatments exhibited no significant differences (Figures 4 and 5).

At present, only the sulforhodamine B (SRB) colorimetric assays for cytotoxicity screening were done on the bark or outer covering of roots but not on A. macrophylla tree bark. Results from the literature stated that indole derivatives found in the rhizome outer covering of A. macrophylla had antiproliferative action (using the SRB assay) on MOR-P and COR-L23 carcinomas because of the bisindole component.26O-Acetylmacralstonine, villalstonine, and macrocarpamine were also established to influence definite actions on normal mammary fibroblasts, as well as on these specific immortalized cancers: StMl1 1a (skin cancer), Caki-2 (kidney cancer), MCF-7 (breast cancer), and LS174T (colon cancer) with IC50 values ranging 2–10 μM.26 Another work showed that methanolic extracts of root barks containing O-methylmacralstonine, talcarpine, villalstonine, pleiocarpamine, and macraistonine exhibited high cytotoxicity on MOR-P and COR-L23.27

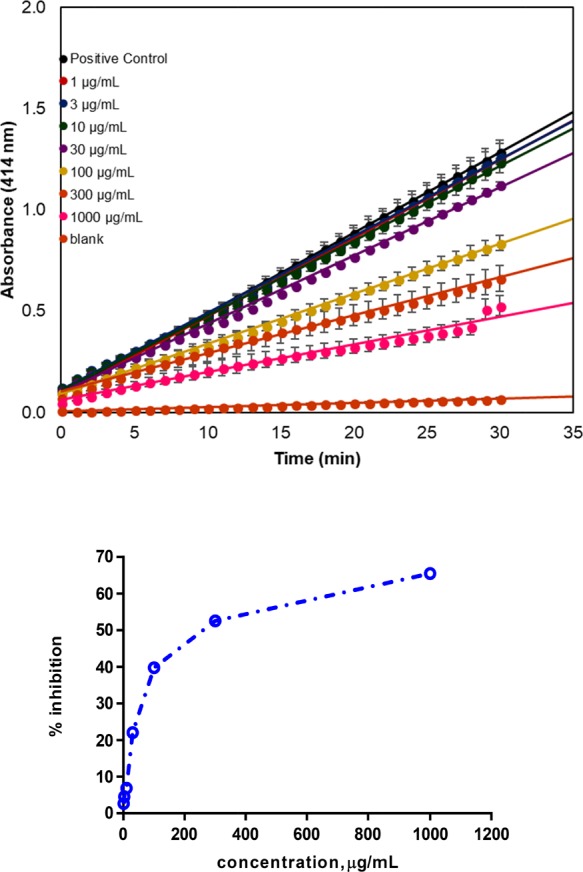

2.5. Inhibitory sPLA2 Activity of AM

The sPLA2 action of 100 ppm N. philippinensis (NPV) was examined with the potential inhibitor AM. Plant extracts ranging from 1 to 1000 μg/mL (seven dilutions) were established in the presence of 100 μg/mL Philippine cobra venom. Percent inhibition brought about by the inhibitors was determined and established on the computed sPLA2 activities.

The AM bark showed inhibitory phospholipase activity as shown by the IC50 concentration of 297.27 ± 9.33 μg/mL (Figure 6). An alkaloid found in the Solanaceae family, atropine, was discovered to impede the venom of Daboia russelli.28 Phytochemical compounds, coumestan and steroids (β-sitosterol and stigmasterol) extracted from the alcoholic rhizome preparations of Pluchea indica bypassed oxidative degradation of lipids and superoxide dismutase action stimulated through envenoming.29 Lupeol moderately prevented the hemorrhage, edema, procoagulant, and myotoxic events caused by Bothrops venom.30 These aforementioned constituents could be the cause for the observed N. philippinensis antivenom activity, which solicits further studies.

Figure 6.

Linear regression analysis of the variation in absorbance (ΔA414) as the slope (top) and inhibitory outcome of AM in contradiction of sPLA2 activity from NPV (bottom).

A member of the same genus, A. scholaris (AAS) aqueous solution was found to significantly neutralize Vipera russelli venom (VRV) stimulating an increase in serum alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, and creatinine in Swiss albino animal models incubated with VRV (0.5 and 1 μg) and AAS concoction (200 mg/kg).31 The water decoction of AAS inhibited VRV minimum lethal action, minimum edema activity, minimal defibrinogenating activity, and minimum necrotizing action in mice weighing approximately 18–20 g.32

In this work, AM bark was found to be an efficient antioxidant, the assessment of the effectiveness of AM on the four immortalized cancer cell lines revealed that the integrity of MCF-7, H69PR, and HT-29 consistently decreased in all the trials, and the action of cytotoxicity was analogous to the positive control Zeocin. For the most part, trials observed in the mutant cell lines indicated low half maximal inhibitory concentrations (<7 μg/mL), which were acquired for all of the trials. MCF-7 was highly responsive to AM, while the least responsive to AM was THP-1. Wild-type HDFn trials incubated with AM were substantiated to be noncytotoxic and gave half maximal inhibitory concentrations of greater than 100 μg/mL, whereas Zeocin-treated normal cells reached their half maximal inhibitory concentrations at less than 5.00 μg/mL. The results of this work on the crude MEOH/DMSO extracts from A. macrophylla, which consisted primarily of alkaloids and triterpenoids, could be the rationale for further development of this preparation, through additional bioassays, as a candidate for chemotherapeutic drugs or as a supplementation in the management of human colorectal cancer, human breast adenocarcinoma, and human small cell lung carcinoma. AM bark has shown in vitro prohibitory events against sPLA2 granting that there has been no preceding information of this phenomenon. NPV neutralization by constituents of AM bark or in combination therapy with antivenom serum could be suitable inhibitors to the enzymatic toxins from snake envenoming.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Preparation Protocol

The outer coverings of A. macrophylla trunks were gathered in Mariveles, Bataan, Philippines and was identified by Virgilio Linis, a botanist from the Biology Department, De La Salle University. The bark was ground followed by soaking ∼3.0 g of the powdered biomass in 20 mL of dichloromethane (DCM) for 3 h. Extracts were filtered and then dried under nitrogen for 1 h. The crude extract yielded approximately 0.7 g. Powdered biomass of each species was soaked in a polar extraction solvent to target the isolation of phenolic acids. This solution was made up of a 50:50 MeOH/DMSO ratio according to the method used by Harukaze et al.19

3.2. GC–EI-MS Parameters

Crude extracts from both solvents were scrutinized by GC–EI-MS. An Agilent GC MS 7890B, equipped with a HP-5 ms (5% phenyl methylsiloxane) Ultra Inert column (30 m × 250 mm × 0.25 mm) with ultrapure helium gas as the mobile phase, was employed for the analysis of low-boiling-point components. Helium gas was delivered at 1 mL/min, while maintaining pressure at 8.2 psi, with a rate of 36.62 cm/s and holdup interval of 1.37 min. The splitless inlet was held at 250 °C, at 8.2 psi, and an overall stream of 24 mL/min, with a septum purge stream velocity of 3 mL/min. The temperature for the injector was stipulated at 250 °C. The temperature program started at 70 °C with a programmed linear ramp of 2 °C/min until 135 °C and was held at this temperature for 10 min. Another temperature increase was achieved at 4 °C/min until 220 °C and was maintained for 10 min. The temperature was then increased to 270 °C at a ramp of 3.5 °C/min and was held at 37 min.

Compound identification was done using the NIST Archive 2.0, and percent peak area average was calculated from the subsequent total ion chromatograms (TIC). The consequential results were authenticated by the evaluation of the constituents corresponding to their elution succession with their comparative retention indices on a midpolar column. The retention indices were processed for the identified analytes utilizing a sequence of n-alkanes. All tests were performed in triplicate.

3.3. EDX Analysis

Dehydrated samples of AM bark were prepared in a 10 mm Mylar cup for elemental analysis using an EDX-7000 with a collimator set at 10 mm under vacuum.

3.4. Antioxidant Assay

The antioxidant potential of protonated AM leaf methanolic preparations was measured by an adapted DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) protocol of Viturro et al.20 Approximately ∼0.5 g of powdered biomass of each species was added to 1 mL of an extraction solvent made up of 7.0 mL of MeOH, 2.95 mL of H2O, and 0.05 mL of HCl. The biomass was soaked for 3 h and was filtered to yield approximately ∼50 mg of crude extract. Samples were then dried under nitrogen gas for 2 h.

The DPPH mixture (0.2 mM) was formulated by diluting 3.94 mg of DPPH in 50 mL of methanol. An initial solution of AM was prepared at 4 mg of crude extract in 1 mL of methanol. The blank was made with 1 mL of this solution in addition to 1 mL of methanol. One mL of the 4 mg/mL stock was added to a 10 mL test tube along with 1 mL of the 0.2 mM DPPH solution. A total of eight concentrations from 17.5 to 0.27 mg/mL were made by serial dilution. The absorbances were read at 515 nm (UV–vis Shimadzu 2900) after samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. IC50 is defined as the sample concentration at which 50% of the free radicals are removed. This is determined by calculating the DPPH free radical scavenging percentages. This is computed by the formula:

| 1 |

3.5. Cell Viability Assay

The pharmacognosy of the dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) extracts from AM was tested on the succeeding immortalized cell lines purchased from ATCC, Manassas, Virginia, USA (breast cancer (MCF-7), colon cancer (HT- 29), small cell lung carcinoma (H69PR), human acute monocytic leukemia (THP-1)) and a primary culture of normal human dermal fibroblast neonatal (HDFn) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Gibco, USA). Culture and maintenance were done in DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium and 10% fetal bovine serum with 1× antibiotic–antimycotic) (Thermo Fisher, Invitrogen, USA) and were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity.

The cytotoxic activities of the AM extracts were determined using the PrestoBlue viability assay. The protocol detects viable cells by virtue of actively present mitochondrial reductases that metabolically reduce the resazurin dye (nonfluorescent blue) to resorufin (highly fluorescent red). The 96 well culture plates were measured at 570 nm to measure the resorufin produced, which was correlated to the number of viable cells.

Cells passaged in wells with viable counts of 1.0 × 104 cells/mL in each well were allowed to form monolayers overnight, except for THP-1 that are nonadherent cells. After overnight incubation,100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.12, 1.56, and 0.78 μg/mL solutions of AM extracts were introduced into the wells. After 72 h, 10 μL of PrestoBlue was placed in the trials. Further incubation was done for 1 h to allow optimal reactions to take place. Wells with no AM added served as negative untreated controls, and wells with Zeocin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Gibco, USA) served as the positive control. Zeocin, which is a DNA intercalating antibiotic of the bleomycin/phleomycin family, is cytotoxic to cells growing aerobically from 0.5 to 1000 μg/mL. Spectrophotometry was carried out using a BioTek ELx800. Optical density (O.D.) values were ascertained to derive percent cell viability following the equation below:

| 2 |

Nonlinear regression and statistical analyses were achieved using the software GraphPad Prism 7. The IC50 (inhibitor concentration leading to 50% reduction of cell viability) was also inferred from nonlinear regression analysis. All trials were performed in three replicates and are shown as mean ± SEM. The Brown–Forsythe analysis (F test) was utilized to discern the variances in the best-fit parameters and dose–response curve fits. One-way ANOVA (p < 0.05) was accomplished to clarify disparities between datasets, in conjunction with Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05).

3.6. In Vitro Inhibitory sPLA2 Activity

The inhibitory effects of AM (MeOH/DMSO) extracts were determined against northern Philippine Cobra or Naja philippinensis Taylor (NPV) venom sPLA2 using the Secretory Phospholipase A2 Assay Kit (Cat. No. ab133089). The following reagents were used and formulated according to the manufacturer’s instructions: assay buffer (10×), 5,5′-dithio-bis-(2-nitro-benzoic acid) (DTNB), diheptanoyl thio-PC substrate, bee venom (control), and a 96 well polystyrene F-bottom clear microplate.

The venoms and AM were reconstituted in methanol or DMSO to achieve a 100 mg/mL concentration, which was serially diluted to1000 to 1 ppm. The blank was composed of 5 μL of DMSO, 10 μL of DTNB, and 10 μL of assay buffer, while the positive control contained 5 μL of DMSO, 10 μL of DTNB, and 10 μL of NPV. The experimental wells included 5 μL of AM inhibitor in DMSO, 10 μL of DTNB, and 10 μL of NPV. After addition of 200 μL of diheptanoyl thio-PC substrate into each well, absorbance was read at 414 nm using a Corona Electric Multimode Microplate Reader (MTP-800). Percent inhibition was verified based on the determined sPLA2 inhibition. In addition, the concentration of AM generating 50% inhibition (IC50) was stated.

| 3 |

Here, Xcontrol is the sPLA2 activity of positive control (100 μg/L NPV) and Xsample is the sPLA2 activity in the presence of inhibitor (AM). The absorbance values were corrected against the blank sample (DMSO).

Acknowledgments

The authors are respectfully grateful to the De La Salle University Science Foundation and the University Research Coordination Office for the research grant given for the completion of this project. Also, the authors greatly appreciate the indispensable assistance and support that Professor Michio Murata of the Department of Chemistry, Graduate School of Science, Osaka University generously gave us.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AM

Alstonia macrophylla bark

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- EDX

energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

- GC–EI-MS

gas chromatography–electron ionization-mass spectrometry

- IC50

half maximal inhibitory concentration Immortalized cell lines

- MCF-7

human breast adenocarcinoma cell line

- HT-29

human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line

- H69PR

Homo sapiens small cell lung carcinoma

- THP-1

human acute monocytic leukemia cell line

- HDFn

primary culture of normal human dermal fibroblast neonatal

- MeOH

methanol

- NPV

Naja philippinensis Taylor venom

- sPLA2

secretory phospholipase A2

- ppm

parts per million

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Koyama K.; Hirasawa Y.; Hosoya T.; Hoe T. C.; Chan K. L.; Morita H. Alpneumines A–H, new anti-melanogenic indole alkaloids from Alstonia pneumatophora. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 4415–4421. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama K.; Hirasawa Y.; Nugroho A. E.; Hosoya T.; Hoe T. C.; Chan K. L.; Morita H. Alsmaphorazines A and B, Novel indole alkaloids from Alstonia pneumatophora. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4188–4191. 10.1021/ol101825f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macabeo A. P. G.; Krohn K.; Gehle D.; Read R. W.; Brophy J.J.; Cordell G. A.; Franzblau S. G.; Aguinaldo A. M. Indole alkaloids from the leaves of Philippine Alstonia scholaris. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 1158–1162. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim A. A.; Garson M. J.; Craik D. J. New indole alkaloids from the bark of Alstonia scholaris. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 1591–1594. 10.1021/np0498612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S. J.; Low Y. Y.; Choo Y. M.; Abdullah Z.; Etoh T.; Hayashi M.; Komiyama K.; Kam T. S. Strychnan and Secoangustilobine A Type Alkaloids from Alstonia spatulata.Revision of the C-20 Configuration of Scholaricine. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 1891–1897. 10.1021/np100552b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S. K.; Padhi L.; Leyssen P.; Liu M.; Neyts J.; Luyten W. Antimicrobial, Anthelmintic, and Antiviral Activity of Plants Traditionally Used for Treating Infectious Disease in the Similipal Biosphere Reserve, Odisha, India. Front Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 658. 10.3389/fphar.2017.00658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni M. P.; Juvekar A. R. Effect of Alstonia scholaris (Linn.) R.Br. on stress and cognition in mice. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2009, 47, 47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meena A.; Nitika G.; Nain J.; Meena R. P.; Rao M. M. Review on ethanobotany, phytochemical and pharmacological profile of Alstonia scholaris. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2011, 2, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Changwichit K.; Khorana N.; Suwanborirux K.; Waranuch N.; Limpeanchob N.; Wisuitiprot W.; Suphrom N.; Ingkaninan K. Bisindole alkaloids and secoiridoids from Alstonia macrophylla Wall. ex G. Don. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 798–804. 10.1016/j.fitote.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay D.; Arunachalam G.; Ghosh L.; Mandal A. B. CNS activity of Alstonia macrophylla leaf extracts: an ethnomedicine of Onge of Bay Islands. Fitoterapia 2004, 75, 673–682. 10.1016/j.fitote.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay D.; Arunachalam G.; Ghosh L.; Rajendran K.; Mandal A. B.; Bhattacharya S. K. Antipyretic activity of Alstonia macrophylla Wall ex A. DC: an ethnomedicine of Andaman Islands. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 8, 558–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A. K.; Dutta B. K.; Sharma G. D. Medicinal plants used by different tribes of Cachar district, Assam. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2008, 7, 446–454. [Google Scholar]

- Christophe W.Medicinal Plants of the Asia-Pacific: Drugs for the Future; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.: Singapore, 2006, pp. 447–450. [Google Scholar]

- Dagar H. S., Dagar J. C.. Economic Botany; Springer on behalf of New York Botanical Garden Press, 1991, pp. 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Asolkar L. V., Kakkar K. K., Chakre O. J.. Second Supplement to Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants With Active Principles. Part 1; Publications and Information Directorate, CSIR: New Delhi, India, 1992, pp. 51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay D.; Maiti K.; Kundu A. P.; Chakraborty M. S.; Bhadra R.; Mandal S. C.; Mandal A. B. Antimicrobial activity of Alstonia macrophylla: a folklore of bay islands. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 77, 49–55. 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arunachalam G.; Bag P.; Chattopadhyay D. Phytochemical and phytotherapeutic evaluation of Mallotus peltatus (Geist.) Muell. Arg. var acuminatus and Alstonia macrophylla Wall ex A. DC: Two ethno medicine of Andaman Islands, India. J. Pharmacogn. Phytother. 2009, 1, 001–013. [Google Scholar]

- Khyade M. S.; Kasote D. M.; Vaikos N.P. Alstonia scholaris (L.) R. Br. and Alstonia macrophylla Wall. ex G. Don: A comparative review on traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 1–18. 10.1016/j.jep.2014.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harukaze A.; Murata M.; Homma S. Analyses of Free and Bound Phenolics in Rice. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 1999, 5, 74–79. 10.3136/fstr.5.74. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viturro C.; Molina A.; Schmeda-Hirschmann G. Free radical scavengers from Mutisia friesiana (Asteraceae) and Sanicula graveolens (Apiaceae). Phytother. Res. 1999, 13, 422–424. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid I. R.; Horne A.; Mason B.; Ames R.; Bava U.; Gamble G. D. Effects of calcium supplementation on body weight and blood pressure in normal older women: a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 3824–3829. 10.1210/jc.2004-2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid I. R.; Mason B.; Horne A.; Ames R.; Clearwater J.; Bava U.; Orr-Walker B.; Wu F.; Evans M. C.; Gamble G. D. Effects of calcium supplementation on serum lipid concentrations in normal older women:: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Med. 2002, 112, 343–347. 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)01138-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian A.; Frassetto L. A.; Sellmeyer D. E.; Morris R. C. Jr. The Evolution-Informed Optimal Dietary Potassium Intake of Human Beings Greatly Exceeds Current and Recommended Intakes. Semin. Nephrol. 2006, 26, 447–453. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marguí E.; Queralt I.; Hidalgo M. Application of X-ray fluorescence spectrometry to determination and quantitation of metals in vegetal material. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2009, 28, 362–372. 10.1016/j.trac.2008.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G.; Kumar P. Evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of flavonoids of Withania somnifera L. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 73, 473–478. 10.4103/0250-474X.95656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keawprdub N.; Houghton P. J.; Eno-Amooquaye E.; Burke P. J. Activity of extracts and alkaloids of thai Alstonia species against human lung cancer cell lines. Planta Med. 1997, 63, 97–101. 10.1055/s-2006-957621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keawpradub N.; Eno-Amooquaye E.; Burke P. J.; Houghton P. J. Cytotoxic activity of indole alkaloids from Alstonia macrophylla. Planta Med. 1999, 65, 311–315. 10.1055/s-1999-13992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigneshwaran N.; Madhusudana S.; Pramod S. N. Pharmacological Evaluation of Analgesic and Antivenom Potential from the Leaves of Folk Medicinal Plant Lobelia nicotianaefolia. Am. J. Phytomed. Clin. Ther. 2014, 2, 1404–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes A.; Saha A.; Chatterjee I.; Chakravarty A. K. Viper and cobra venom neutralization by β-sitosterol and stigmasterol isolated from the root extract of Pluchea indica Less. (Asteraceae). Phytomedicine 2007, 14, 637–643. 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meenatchisundaram S.; Parameswari G.; Subbraj T.; Michael A. Anti-venom Activity of Medicinal Plants – A Mini Review. Ethnobotanical Leafl. 2008, 12, 1218–1220. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R.; Mana K.; Sarkhel S. Ameliorating effect of Alstonia scholaris L. bark extract on histopathological changes following viper envenomation in animal models. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 988–993. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkhel S.; Ghosh R. Preliminary Screening of Aqueous Alstonia Scholaris Linn Bark Extract for Antivenom Activity in Experimental Animal Model. IOSR J. Dental Med. Sci. (IOSR-JDMS) 2017, 16, 120–123. 10.9790/0853-160508120123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]