Abstract

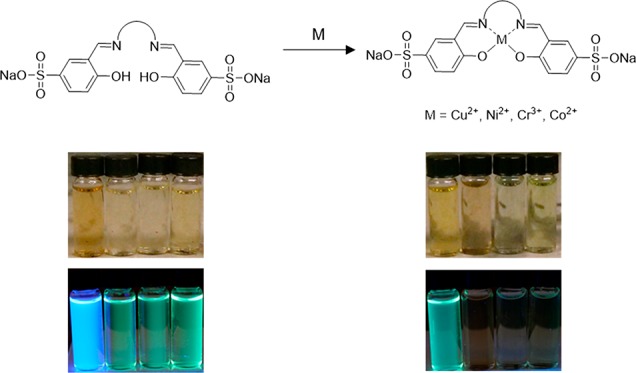

The ability to detect and selectively identify trace amounts of metal ions is of major importance for drinking water identification and biological studies. Herein, we report a series of water-soluble Schiff-base ligands capable of being fluorescent and colorimetric sensors for metal ions. Upon coordination of the metal ion to the ligand, quenching of fluorescence is observed, typically in a 1:1 ratio. The selectivity of metal ions Cu2+, Ni2+, Cr3+, and Co2+ is exhibited via fluorescence quenching accompanied by colorimetric changes, whereas that of Ag+ and Co2+ is observed through colorimetric changes alone. Additionally, pH sensing studies were performed for the potential use of these ligands in biological applications.

Introduction

Metal ions are of great importance in the realm of biology and environmental chemistry.1 In the field of biology, metal ions are essential elements that function in the human body as cofactors, metabolic regulators, and oxygen transporters.2,3 Despite the important roles of metal ions, the accumulation or deficiency of certain metal ions can cause a series of severe diseases. For example, cobalt, a cofactor of vitamin B12, leads to cardiac arrest when accumulated in excess4 and chromium, a metal ion used for the regulation of glucose, in deficiency causes elevated levels of glucose in blood and urine.5 One of the ways that dangerous levels of metal ions enter our bodies is through contaminated drinking water via the erosion of natural deposits.6,7 In certain cases, this can prove to be toxic upon consumption as recently seen in the highly publicized lead-contaminated drinking water crisis of Flint, Michigan.8−10 For these reasons, the synthesis and design of reliable molecular sensors for the detection of metal ions are of great importance.

A variety of sensors have been reported for the detection of metal ions including the use of high-resolution differential surface plasmon resonance sensors,11 acid-free synthesis of high-quality graphene quantum dots for aggregation-induced sensing,12 electrochemical sensors,13−16 and fluorescent and colorimetric sensors.17,18 Among the various detection techniques available, detections through fluorescence changes or colorimetric changes are the most convenient methods because of the sensitivity and ease of use, respectively.19,20

Much success has been shown in using fluorescent or colorimetric sensors to detect metal ions in aqueous media to include Cu2+, Zn2+, and Fe3+ 21 and heavy metal ions Pt2+,22 Pb2+, Cd2+, and Hg2+.17,18 Although many of these sensors successfully detect trace amounts of metal ions in water, the high carbon-to-hydrogen bonding atom ratio for many of these molecules ironically makes them insoluble in pure aqueous media, a factor which is absolutely necessary for biological applications. Therefore, designing water-soluble sensors capable of detecting metal ions in pure aqueous media is advantageous.

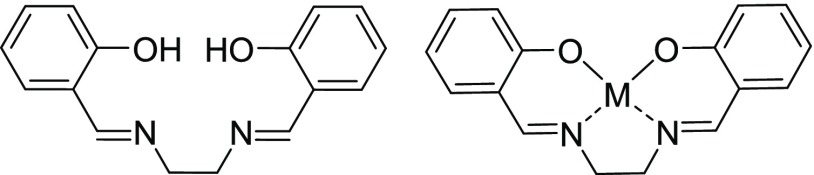

Recently, Zhou et al. showed the addition of sulfonyl groups on the salen backbone of a Schiff-base greatly increases the water solubility of the molecule.23 A Schiff-base is a compound obtained from a one-step, one-pot condensation reaction of an aldehyde or ketone with an amine.24 One of the most utilized examples of a Schiff-base is the salen ligand (Figure 1) which is derived from a diamine combined with 2 equiv of salicylaldehyde.

Figure 1.

Salen Ligand and salen ligand complexed to a metal ion (M).

The salen ligand has two covalent and two coordinate covalent sites orientated in planar geometry making it ideal for the equatorial coordination of transition metal ions while still having two open axial sites for additional bonding as shown in Figure 1.25 Additionally, this ligand and its derivatives are easy and inexpensive to prepare.26 Although the most common use for salen ligands is for enantioselective catalysis,27−30 they are also valuable in coordinating many different types of metal ions in various oxidation states.27

Aromatic Schiff-bases are highly sought after as sensors because of the fluorescent complexes they make through nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur donor atoms.22,25,31 Additionally, Schiff-bases are known to have biological activities such as anticancer activity32,33 which tends to increase when complexed with metal ions.34 Much efforts have been made to synthesize fluorescent Schiff-base compounds which are selective, sensitive, water soluble, and suited for monitoring biological processes.21,35−38 Currently, the length of these Schiff-base sensors are limited to two carbons in the amine linker. Access to longer length amine linker could expand the possibility of complexing larger metal ions or metal complexes. For example, Signorella et al. recently showed antioxidant activity with a water-soluble Mn(III) sulphonato-substituted Schiff-base ligand using a three-carbon backbone linker.39 In addition, the pH sensing application of these Schiff-base derivatives are rarely reported, despite the fact that they are simple and common. Herein, we report a series of water-soluble sulfonyl Schiff-bases including a three- and four-carbon chain linker capable of detecting common metal ions found in drinking water using fluorescence and colorimetric changes. Furthermore, we investigate the pH sensing ranges of these ligands for possible use in biological applications.

Results and Discussion

Physical Properties of Ligands

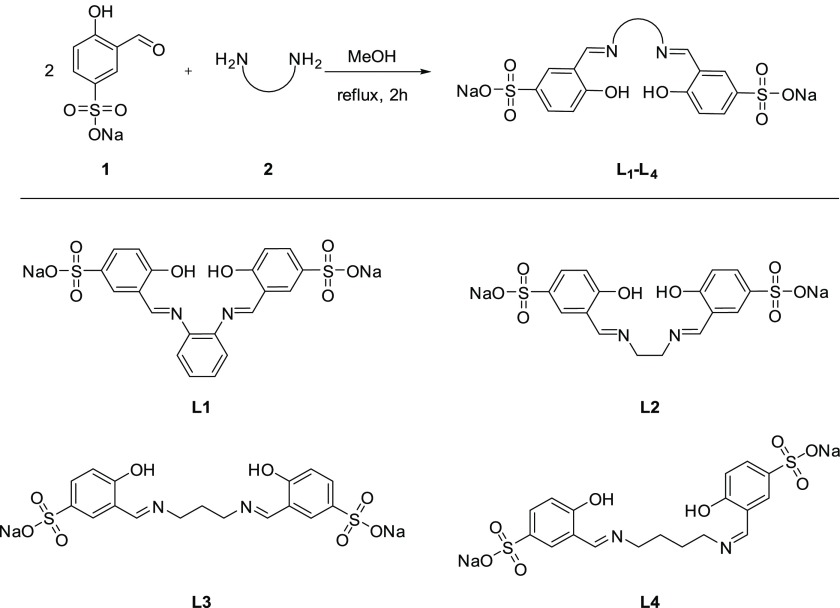

Studies began with the well-established synthesis of the sulfono aldehyde (1)36 followed by the condensation of 1 with the respective diamine linkers (2) to afford ligands L1–L4 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Chemical Synthesis and Structure of L1–L4.

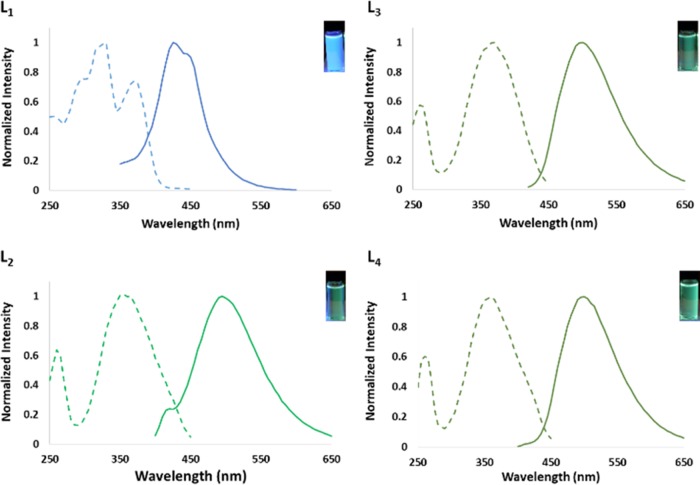

With ultraviolet (UV) light excitation, the ligands absorb and emit in the blue-green range of the visible spectrum giving an excitation spectrum in the 320−450 nm range and an emission spectrum in the 430–500 nm range, as seen in Figure 2. As expected, under longer wavelength light, the higher energy L1 emits blue, whereas L2–L4 emit green (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Excitation and emission spectra of L1–L4. Excitation spectra are shown with dashed lines; emission spectra are shown with solid lines. Picture insets show L1–L4 irradiated with long wavelength light. L1 emits blue, whereas L2–L4 emit green. Concentrations for L1 are 10 μM in deionized (DI) water and 1 mM in DI water for L2–L4.

A summary of the UV/vis absorption spectral data for L1–L4 is listed in Table 1. Of the four ligands, L1 had the highest quantum yield when excited with UV light with a value of 0.330 as compared to 0.055, 0.002, and 0.002 for L2, L3, and L4, respectively. The vast difference in quantum yield of L1 from L2−L4 may be due to the additional conjugation from the phenyl ring of the amine linker. The higher quantum yield of L1 allows for more sensitive quenching studies, whereas red-shifted ligands L2–L4 allow for emission detection in a lower energy region of the visible spectrum.

Table 1. Spectral Properties of Ligands.

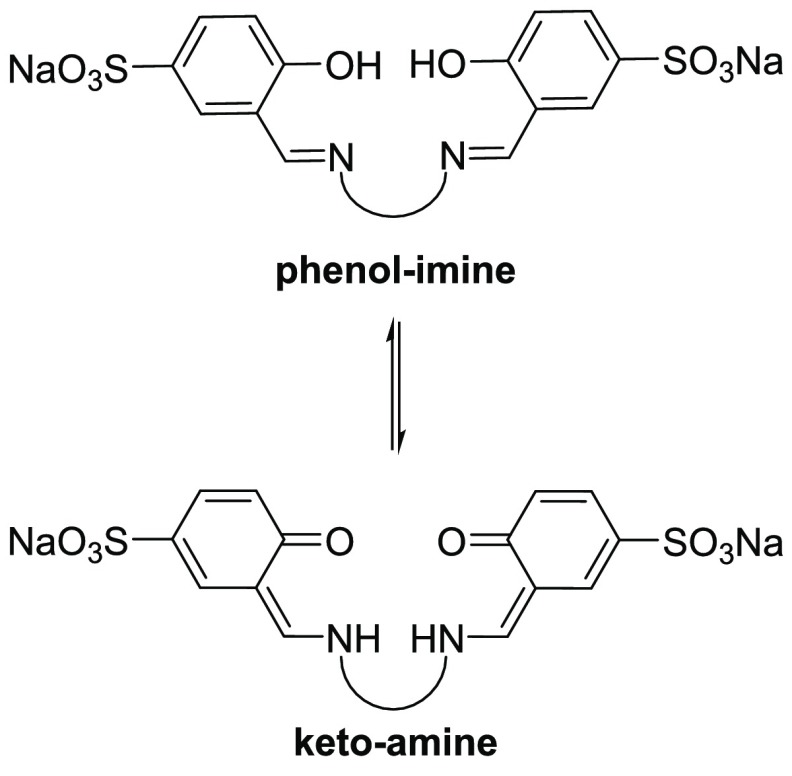

The effects of tautomerization in 2-hydroxy Schiff bases have been extensively studied and are essential to their biological and chemical properties.40−45 The tautomeric forms which can exist in equilibrium for L1–L4 are the phenol-imine and the keto-amine tautomers as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Phenol-imine and keto-amine tautomeric equilibria expected for L1–L4 in solution.

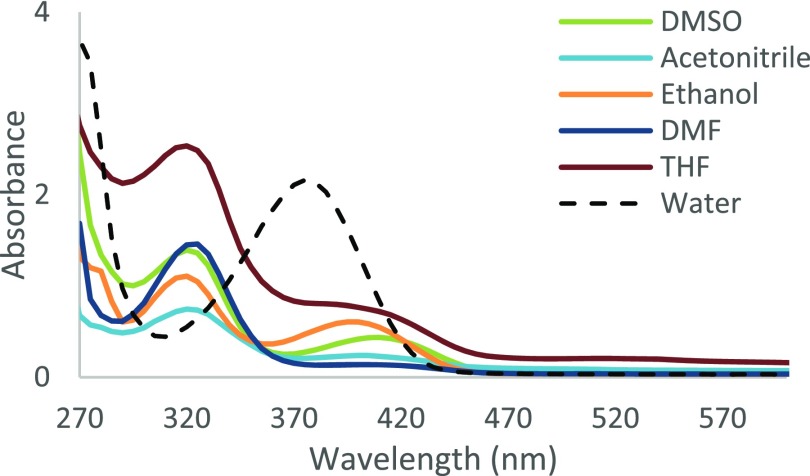

UV–vis spectroscopy can be used to determine the existence of tautomerism within a molecule since the keto and the phenol form will absorb at different wavelengths. It has been reported that the formation of a new higher wavelength band (generally >400 nm) in the presence of polar solvents indicates the presence of the keto-amine isomer of Schiff-base.46Figure 4 shows two distinct bands observed at wavelengths 280–360 nm (phenol-imine) and 360–450 nm (keto-amine) for L4.

Figure 4.

Absorption spectrum of L4 in an array of polar solvents.

In polar solvents dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), acetonitrile (CH3CN), ethanol (EtOH), dimethylformamide (DMF), and tetrahydrofuran (THF), the phenol-imine tautomer is dominant for L4. The percentages of the keto-amine tautomer determined in solution via UV–vis46,47 for L2–L4 are given in Table 2.

Table 2. UV–Vis Spectral Data for L2–L4.

| ligand | solvent | % keto-aminea |

|---|---|---|

| L2 | DMSO | 31 |

| CH3CN | 20 | |

| EtOH | 22 | |

| DMF | 17 | |

| L3 | DMSO | 17 |

| CH3CN | 21 | |

| EtOH | 29 | |

| DMF | 8 | |

| L4 | DMSO | 24 |

| CH3CN | 24 | |

| EtOH | 37 | |

| DMF | 9 | |

| THF | 24 |

Calculated using the formula as outlined by Hayvali and Yardimci.46

When water is the solvent, the absorption max peak of the dominant tautomer shifts from 325 to 380 nm indicating that in aqueous media, the keto-amine isomer is the dominant and active form. L2 and L3 also show the keto-amine isomer as the dominant and active form and the spectra of these ligands are shown in Figure S1. The absorption bands for L1 were not distinct for the relative isomers (see Figure S2); however, the absorption was below 400 nm, indicating that L1 largely exist in the phenol-imine isomer.

Fluorescence Quenching Studies with Ligands

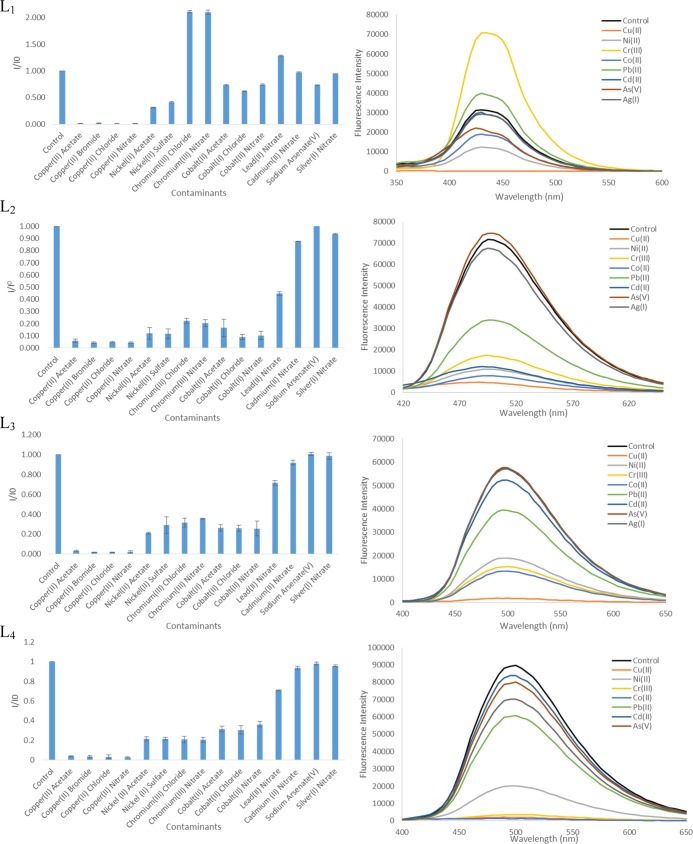

Quenching studies began by testing the sensory levels of the ligands with common metal ions found in water (Cu2+, Ni2+, Cr3+, Co2+, Pb2+, Cd2+, As5+, and Ag+). The effects of 1 equiv of metal ions on fluorescence intensity of L1–L4 are shown in Figure 5. All ligands were titrated with up to 4 equiv of the respective metal ions as shown in Figure S2. Because of the higher quantum yield and preferred phenol-imine tautomeric form of L1, measurements for L1 were 10 μM, whereas those for L2–L4 were 1 mM.

Figure 5.

Effect of different metal ions on the fluorescence intensity of L1 (10 μm) and L2–L4 (1 mM) in a 1:1 ratio. Emission spectra of the ligands in the presence of 1 equiv of varying metals.

Metal ions Cu2+, Ni2+, and Co2+ quench all four ligands with Cu2+ completely quenching the fluorescence intensity for all four ligands. Surprisingly, the fluorescence for L2–L4 were quenched by Pb2+ and Cr3+, whereas L1 showed a slight increase in fluorescence intensity when complexed to Pb2+ and almost a doubling in intensity for Cr3+. The increase in fluorescence intensity for L1 is most likely attributed to the complexation of these metal ions with the phenol-amine tautomer forming a different complex from that of the keto-amine tautomer preferred by L2–L4. Metal ions Cd2+, As5+, and Ag+ did not show a significant change in the fluorescence intensity for all of the respective ligands.

Control experiments that were run using counterions F–, Cl–, I–, NO2–, and NO3– showed no quenching of fluorescence in the presence of ligands (Figure S3), suggesting that the quenching of the ligands is from the complexation of the indicated respective metal ions. Additionally, ionic strength studies were performed with all four ligands in the presence of 1000, 100, 10, and 1 mM solutions of NaCl, Na2SO4, MgCl2, and MgSO4. Overall, the ligands did not display significant changes in the sensing potential of the metal ions in the presence of these ions (see Figure S4). A blue shift of the emission spectrum occurred for L2–L4 as the ionic strength increased for the magnesium salts; however, the intensity of the emission spectrum remained the same and the ligands were still quenched by the metal ions. An example of this is shown in Figure S5 with L2 still being effectively quenched in the presence of increasing equivalents of Cu2+.

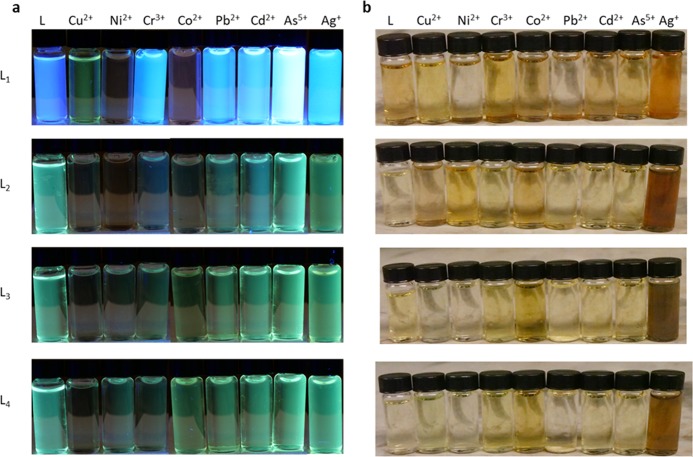

Colorimetric Quenching Studies with Ligands

Certain advantages for each ligand lie within its ability to identify which metal ion is present by using a combination of fluorescence intensity and colorimetric change. A photo of all ligands in the presence of 1 equiv of different metal ions under UV–vis and daylight is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Photographs of L1 (10 μM) and L2–L4 (1 mM) (a) under long wavelength light excitation and (b) under daylight upon addition of 1 equiv of varying metal ions.

In the case of L1 under long wavelength light excitation, quenching with Cu2+ selectively changes the color from blue to green and for Ni2+ and Co2+, L1 changes from blue to red (Figure 6a). L2 turns red when quenched with 1 equiv of Ni2+ compared to clear when quenched with 1 equiv of Co2+. L3 and L4 do not show significant changes in color under long wavelength light excitation upon the addition of metal ions with the exception of Cu2+ in which the solution turns clear. While significant changes in fluorescent color is not detectable for L3 and L4, one advantage of L3 and L4 over L1 and L2 is their ability to access the 450–650 nm range of the visible spectrum which is advantageous for other possible sensing applications. Colorimetric changes seen by the naked eye are shown in Figure 6b. A significant color change is seen for all of the ligands in the presence of Ag+ in which the solutions change to an orange or reddish-orange color.

Competitive reactions between metal ions, such as 1 equiv of Cu2+ and Cr3+ with L1, did not lead to the ability to selectively identify which metal ions were present. L1 in the presence of Cu2+ and Cr3+ showed a decrease in fluorescence intensity of L1 but did not completely quench the ligand as in the case of 1 equiv of Cu2+ alone (see Figure S6). Further distinction could not be concluded by colorimetric changes via UV–vis and daylight.

Detection Limitations of Ligands

To address the concerns of obtaining safe drinking water, the Clean Water Act was established in 197248 which allows the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to implement limitations of metal ions that can become toxic at certain concentrations.49 To evaluate practical applicability, the detection limits of L1–L4 was evaluated. Knowing which metal ions effectively quenched the ligands, we looked at the limits to quenching. According to the EPA, copper has a maximum contaminant level (MCL) of 1.3 ppm (1.3 μM), cadmium has an MCL of 5.0 ppb (5.0 nM), and chromium has an MCL of 0.1 ppm (0.1 μM or 100 nM).

L1 can detect as low as 1 μM with the instrument at maximum parameters (see Figure S7). Therefore, this ligand can be used for the detection of MCL of copper in drinking water which is consistent with a previous report.8 Ligands L2–L4 can detect as low as 2–5 μM (see Figure S4), which is outside the range of MCL detection of copper, cadmium, and chromium. The fact that the phenyl ring linker in L1 increases the sensitivity of Schiff-base ligands suggests that designing a ligand with addition conjugated systems in the aromatic rings of L2–L4 may allow for a higher quantum yield and increase the probability to reach the MCL for additional metal ions.

Biological Application Studies

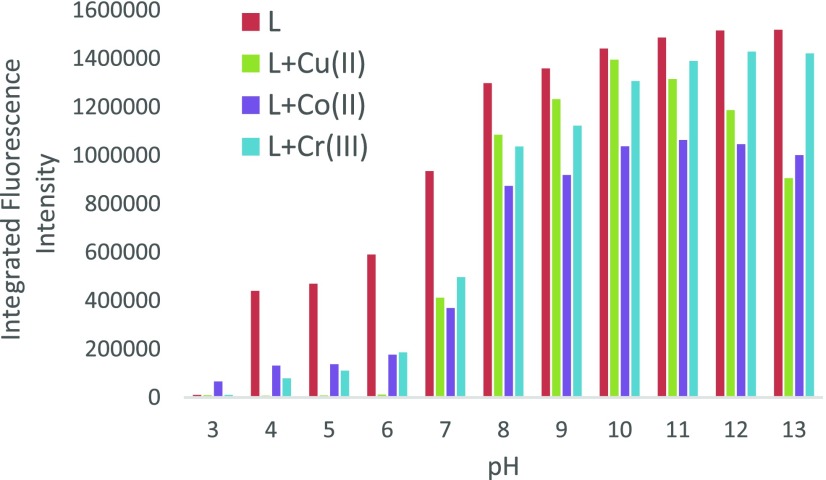

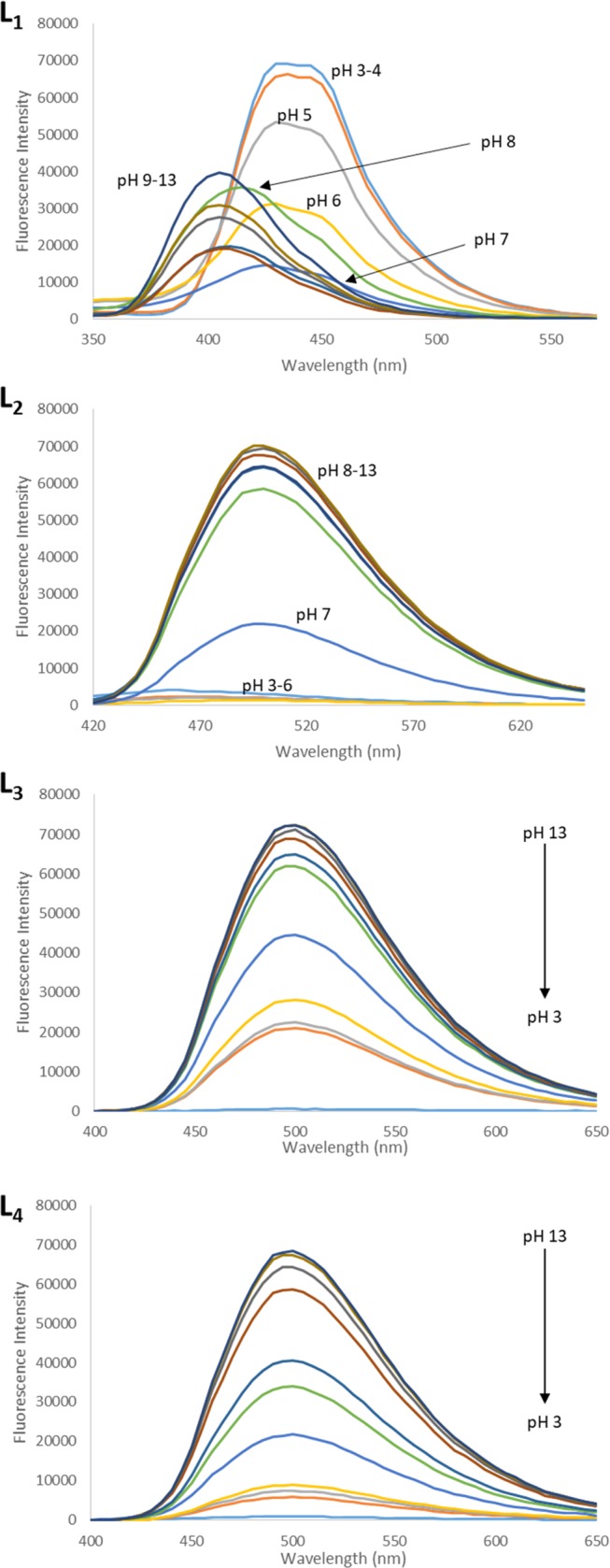

The primary advantages of ligands L1–L4 are they are water soluble and fluorescent, making them appealing for biological applications. The possibilities to explore the ligand for biological purposes were examined through a pH screen. Figure 7 shows the fluorescence intensity in the pH range of 3–11.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence spectra of L1 (10 μM) and L2–L4 (1 mM) at different pH values in 10 mM KH2PO4 buffer. L1 is excited at 300 nm, L2 is excited at 380 nm, and L3 and L4 are excited at 375 nm.

L1 showed interesting results. Upon excitation at 300 nm, a pH range of 3–4 was shown to be most fluorescent followed by a continuous decrease in fluorescence at pH 5–7. At pH 8, a blue shift of the emission spectrum is observed going from an emission maximum of 440 to 420 nm followed by another blue shift of the emission maximum to 400 nm at pH 9–13. These changes can be explained by keto-amine and phenol-imine tautomerization. For L1, pH ranges 3–7 prefer the phenol-imine tautomer, whereas pH ranges 8–13 prefer the keto-amine tautomer (see Figure S8). The pH affects this shift due to the protonation and deprotonation of the phenolic and imine groups in L1. The pKa of a typical phenol is 10, but in the presence of a para-electron-withdrawing group (such as a nitro group), the pKa drops down to 7.91.50 Additionally, the pKa for a Schiff-base imine is around 6.51 In line with the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation,52 one could expect an effective buffer range at ±1 of the pH equal to the pKa. When pH is <5, the L1 is expected to be fully protonated and when pH is >9, L1 is fully deprotonated. Xiang and co-workers reported a significant difference in fluorescence activity upon protonation and deprotonation of the phenol hydrogen of salicyladehdye.55 They reported stronger fluorescence for the deprotonated phenol salicylaldehyde derivatives than their corresponding protonated salicylaldehyde derivatives in solution at room temperature.55 Contrary to salicylaldehyde, the diamine linker of Schiff-base L1 causes the molecule to be more rigid in structure. Since the deprotonated phenol groups will carry a negative charge in pH ranges of 7–9, the two charges repel each other and without the ability to alleviate this interaction via rotation, the ligand resorts to the formation of the keto-amine tautomer.

A linear change in fluorescence was observed for L2 with changing pH, with the highest fluorescence being observed in pH ranges 8–13 followed by a gradual decline in more acidic environments. Similarly, L3 and L4 showed the highest activity in pH ranges 8–11 again with a decrease in activity as the ligand becomes more acidic. These results match the results obtained by Xiang and co-workers with salicylaldehyde derivatives.55

To examine the ability of these ligands to detect amounts of metal ions in biological systems, we investigated the effect of pH on the ligands in the presence of vital metal ions in the human body to include Cu2+, Co2+, and Cr3+. A summary of the results is shown in Figure S9. The ligand which gave the best result in terms of quenching efficiency was L3 (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Plot of the integrated fluorescence intensity for the emission of L3 from 400 to 650 nm in the absence (red bar) and presence (green, purple and blue bar) of 1 equiv of the metal ion against pH. Excitation occurred at 380 nm.

Similar to the free ligand, complexation with metal ions gives the highest fluorescence intensity in the pH ranges of 8–13. Although pH ranges 4–7 show decreased fluorescence intensity, they show a greater quenching efficiency for the metal ions which is advantageous for detecting trace amounts of metal ions. This ligand shows good potential for use in biological applications due to its wide range including physiological pH (pH = 7.4).

Conclusions

In summary, we report the development of four water-soluble Schiff-base ligands capable of detecting select metal ions in water. The ligands synthesized have practical use for the detection of metal ions Cu2+, Ni2+, Cr3+, Co2+, and Pb2+ in water. The selectivity of metal ions Cu2+, Ni2+, Cr3+, and Co2+ is exhibited via fluorescence quenching accompanied by fluorometric and colorimetric changes and Ag+ by daylight colorimetric changes. The advantages of these ligands being water soluble, fluorescent, and stable at physiological pH make them appealing for biological applications. Efforts to increase the quantum yield and sensitivity of the alkyl linker Schiff-bases by additional conjugation in the backbone are currently under investigation.

Experimental Section

Materials and Instrumentation

All reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. Deionized water was used in all experiments. 1H NMR (500 MHz) spectra were recorded in DMSO-d6 and chemical shifts are reported in ppm using tetramethylsilane as the internal standard. UV/vis absorption spectra were recorded using a Greiner Bio-One 96-well microplate and a Synergy H4 Spectrofluorometer with a plate-reading accessory. Instrumental parameters were optimized for each ligand including adjustments of excitation and emission slit widths (9–20 nm), filters, and PMT tube voltage (50–150 V).

Quantum Yield Determinations

Φ was measured by the optical dilute method of Demas and Crosby53 and the procedure was followed as essentially described54 with a standard of quinine sulfate (Φr = 0.55, quinine in 0.0025 M sulfate) calculated by: Φx = ΦST((Gradx/GradST)(ηx2/ηST2)), where the subscripts ST and x denote the standard and ligand, respectively, Φ is the fluorescence quantum yield, Grad is the gradient from the plot of integrated fluorescence intensity vs concentration, and η is the refractive index of the solvent. The optical path length is 1 cm in all cases. Errors for Φ values (±10%) are estimated.

Synthesis of Salicylaldehyde-5-sulfonate Sodium-N-phenyl-5-sulfonato-salicylaldimine (1)

Salicylaldehyde (5 g, 50 mmol) was used essentially as described by Liu55 to afford 1 (6.65 g, 30 mmol) as beige crystals, which matched the reported literature.55 (Yield 60%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz, 25 °C): δ (ppm) 10.23 (s, 1H), 7.83 (s, 1H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 6.90–6.77 (m, 1H).

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Ligands L1–L4

To a round bottom flask was added 1 (1 g, 4.46 mmol) containing 40 mL of methanol. To the reaction mixture, an ethanol solution of the respective amine (0.5 equiv) was added dropwise and then the mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 2 h. The reaction was then filtered and the residue was washed with cold methanol to afford the desired product.

Synthesis of L1

L1 was prepared by the general procedure with o-phenylenediamine (0.241 g, 2.23 mmol) to afford L1 (0.96 g, 83% yield) as orange crystals which matched the reported literature.561H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz, 25 °C): δ (ppm) 8.95 (s, 2H), 7.90 (s, 2H), 7.59 (d, 2H), 7.46 (d, 2H), 7.37 (d, 2H), 6.87 (d, 2H).

Synthesis of L2

L2 was synthesized via the general procedure with ethylenediamine (0.134 g, 2.23 mmol) to afford L2 (1.01 g, 96% yield) as yellow crystals which matched the reported literature.361H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz, 25 °C): δ (ppm) 8.62 (s, 2H), 7.65 (s, 2H), 7.50 (d, 2H), 6.77–6.75 (d, 2H), 3.89 (s, 4H).

Synthesis of L3

L3 was synthesized via the general procedure with 1,3-diaminopropane (0.165 g, 2.23 mmol) to afford L3 (0.511 g, 47% yield) as yellow crystals which matched the reported literature.39 Yield: 0.685 g (2.84 mmol, 64%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz, 25 °C): δ (ppm) 8.58 (s, 2H), 7.66 (s, 2H), 7.50–7.39 (d, 2H), 6.78–6.72 (d, 2H), 3.65 (m, 4H), 2.02–1.80 (m, 2H).

Synthesis of L4

L4 was synthesized via the general procedure with 1,4-diaminobutane (0.197 g, 2.23 mmol) to afford L4 (0.685 g, 61%) as yellow crystals. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 8.58 (s, 2H), 7.64 (s, 2H), 7.48 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 6.73 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 2H), 3.63 (d, J = 22.9 Hz, 4H), 1.64 (d, J = 36.4 Hz, 4H). 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) 166.48, 162.19, 139.26, 130.46, 129.41, 117.47, 116.48, 57.86, 28.45.

General Procedure for Fluorescence Quenching Titrations

Quenching studies were carried out at room temperature using a Synergy H4 Spectrofluorometer with a plate-reading accessory. Stock solutions for the ligands and contaminants were made at 0.1 M using DI water. The solutions were diluted with DI water to obtain concentrations of 10–150 μM. For each ligand, and for each contaminant, 1200 μL of sample were prepared with 10 different contaminant equivalents (including blanks) ranging from 0.1 to 4 equiv. Then, 365 μL of sample was transferred to the wells of a 96-well plate for analysis and read. Spectrofluorometer parameters were adjusted so that controls containing only the ligand gave nearly maximal emission spectra, and then full data sets were collected using those parameters. The assays were performed in triplicate or greater. The mean integrated areas of the visible emission spectra at 1 equiv of the contaminant were used to determine unquenched (I0) and quenched (I) values, and plotted in Excel with standard deviations indicated by error bars. For determining minimal detection limits, more dilute ligand solutions were used (typically 10- to 100-fold lower than those used for the rest of the work described above) that pushed the spectrofluorometer parameters to maximal values, and ligands were titrated with micromolar concentrations of contaminants. When quenching could be detected, it was verified at the lowest concentration in triplicate or quintuplicate.

Procedure for pH Studies

The pH studies were carried out at room temperature using a Synergy H4 Spectrofluorometer with a plate-reading accessory. Stock solutions for the ligands and contaminants were made at 0.1 M. For each ligand, 13 solutions were diluted, respectively, with a 10 mM KH2PO4 buffer with a pH ranging from 3 to 13 to obtain concentrations of 10 μM for L1 and 1 mM for L2–L4. For each ligand and pH, 1000 μL of samples were prepared. Then, 365 μL of sample was transferred to the wells of a 96-well plate for analysis and read. Spectrofluorometer parameters were adjusted so that controls containing only the ligand gave nearly maximal emission spectra, and then full data sets were collected using those parameters. The assays were performed in duplicate or greater. The same procedure was followed for the complexation of Cu2+, Co2+, and Cr3+ with 1 equiv (with respect to the ligand) of the metal ion added to each solution.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by US Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the US Air Force Academy Department of Chemistry.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b02750.

Tautomer graphs—polar solvents (Figure S1), quenching spectra—metal ions (Figure S2), quenching graphs—counterions (Figure S3), emission spectra—ionic strength (Figure S4), quenching spectra—ionic strength (Figure S5), quenching spectrum—competing metal ions (Figure S6), detection limit studies (Figure S7), tautomer graphs—pH studies (Figure S8), quenching graphs—pH studies (Figure S9), and NMRs (Figure S10) (PDF)

Author Present Address

§ Department of Computer Science, Rice University, 6100 Main Street, Duncan Hall 3122, Houston, Texas 77005, United States (D.R.S.).

Author Present Address

‡ Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, Colorado School of Mines, 1500 Illinois Street, Golden, Colorado 80401, United States (M.J.R.).

Author Contributions

† M.J.R. and D.R.S. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Carter K. P.; Young A. M.; Palmer A. E. Fluorescent Sensors for Measuring Metal Ions in Living Systems. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4564–4601. 10.1021/cr400546e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva J. F.; Williams R. J. P.. The Biological Chemistry of the Elements: The Inorganic Chemistry of Life, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, 2001; pp 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I.; Gray H.; Valentine J.; Stiefel E.. Biological Inorganic Chemistry: Structure and Reactivity; Bertini I., Ed.; University Science Books: California, 2007; pp 137–174. [Google Scholar]

- Barceloux D. G.; Barceloux D. Cobalt. J. Toxicol., Clin. Toxicol. 1999, 37, 201–216. 10.1081/CLT-100102420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund H.; Atamian S.; Fischer J. E. Chromium deficiency during total parenteral nutrition. JAMA 1979, 241, 496–498. 10.1001/jama.1979.03290310036012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett R. G. Natural Sources of Metals to the Environment. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2000, 6, 945–963. 10.1080/10807030091124383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg G. F.; Fowler B. A.; Nordberg M.. Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals, 4th ed.; Academic press: Europe, 2014; pp 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pieper K. J.; Tang M.; Edwards M. A. Flint Water Crisis Caused By Interrupted Corrosion Control: Investigating “Ground Zero” Home. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 2007–2014. 10.1021/acs.est.6b04034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw M.; Filippelli G.; Sadler R.; Gonzales C.; Ball A.; Mielke H. Children’s Blood Lead Seasonality in Flint, Michigan (USA), and Soil-Sourced Lead Hazard Risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 358. 10.3390/ijerph13040358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna-Attisha M.; LaChance J.; Sadler R. C.; Champney Schnepp A. Elevated Blood Lead Levels in Children Associated With the Flint Drinking Water Crisis: A Spatial Analysis of Risk and Public Health Response. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 283–290. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.303003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forzani E. S.; Zhang H.; Chen W.; Tao N. Detection of Heavy Metal Ions in Drinking Water Using a High-Resolution Differential Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 1257–1262. 10.1021/es049234z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair R. V.; Thomas R. T.; Sankar V.; Muhammad H.; Dong M.; Pillai S. Rapid, Acid-Free Synthesis of High-Quality Graphene Quantum Dots for Aggregation Induced Sensing of Metal Ions and Bioimaging. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 8051–8061. 10.1021/acsomega.7b01262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L.; Wu J.; Ju H. Electrochemical sensing of heavy metal ions with inorganic, organic and bio-materials. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 63, 276–286. 10.1016/j.bios.2014.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March G.; Nguyen T.; Piro B. Modified Electrodes Used for Electrochemical Detection of Metal Ions in Environmental Analysis. Biosensors 2015, 5, 241. 10.3390/bios5020241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumpu M. B.; Sethuraman S.; Krishnan U. M.; Rayappan J. B. B. A review on detection of heavy metal ions in water–an electrochemical approach. Sens. Actuators, B 2015, 213, 515–533. 10.1016/j.snb.2015.02.122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bansod B.; Kumar T.; Thakur R.; Rana S.; Singh I. A review on various electrochemical techniques for heavy metal ions detection with different sensing platforms. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 94, 443–455. 10.1016/j.bios.2017.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. N.; Ren W. X.; Kim J. S.; Yoon J. Fluorescent and colorimetric sensors for detection of lead, cadmium, and mercury ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3210–3244. 10.1039/C1CS15245A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.-K.; Yook K.-J.; Tae J. A Rhodamine-Based Fluorescent and Colorimetric Chemodosimeter for the Rapid Detection of Hg2+ Ions in Aqueous Media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 16760–16761. 10.1021/ja054855t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Silva A. P.; Gunaratne H. Q. N.; Gunnlaugsson T.; Huxley A. J. M.; McCoy C. P.; Rademacher J. T.; Rice T. E. Signaling Recognition Events with Fluorescent Sensors and Switches. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 1515–1566. 10.1021/cr960386p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho D.-G.; Sessler J. L. Modern reaction-based indicator systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1647–1662. 10.1039/b804436h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. B.; Kim H.; Song E. J.; Kim S.; Noh I.; Kim C. A cap-type Schiff base acting as a fluorescence sensor for zinc(ii) and a colorimetric sensor for iron(ii), copper(ii), and zinc(ii) in aqueous media. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 16569–16577. 10.1039/c3dt51916c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L.; Feng Y.; Cheng J.; Sun N.; Zhou X.; Xiang H. Simple, selective, and sensitive colorimetric and ratiometric fluorescence/phosphorescence probes for platinum(ii) based on Salen-type Schiff bases. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 10529–10536. 10.1039/c2ra21254d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.; Jiang Z.; Wu D.; Xiang H.; Zhou X. A Simple and Efficient Catalytic System for Coupling Aryl Halides with Aqueous Ammonia in Water. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 2010, 1854–1857. 10.1002/ejoc.201000060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff H. The syntheses and characterization of Schiff base. Ann. Chem. Pharm. Suppl. 1864, 3, 343. [Google Scholar]

- Atwood D. A.; Harvey M. J. Group 13 Compounds Incorporating Salen Ligands. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 37–52. 10.1021/cr990008v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calligaris M.; Randaccio L.. Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry; Pergamon Press: London, 1987; Vol. 2, Chapter 20. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzi P. G. Metal–Salen Schiff base complexes in catalysis: practical aspects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004, 33, 410–421. 10.1039/B307853C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrow J. F.; Jacobsen E. N.. Asymmetric Processes Catalyzed by Chiral (Salen)Metal Complexes. In Organometallics in Process Chemistry; Springer: Berlin, 2004; pp 123–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K. C.; Sutar A. K. Catalytic activities of Schiff base transition metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008, 252, 1420–1450. 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gualandi A.; Wilson C. M.; Cozzi P. G. Stereoselective Reactions with Chiral Schiff Base Metal Complexes. CHIMIA Int. J. Chem. 2017, 71, 562–567. 10.2533/chimia.2017.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delahaye É.; Diop M.; Welter R.; Boero M.; Massobrio C.; Rabu P.; Rogez G. From Salicylaldehyde to Chiral Salen Sulfonates – Syntheses, Structures and Properties of New Transition Metal Complexes Derived from Sulfonato Salen Ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 2010, 4450–4461. 10.1002/ejic.201000487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hodnett E. M.; Dunn W. J. Structure-antitumor activity correlation of some Schiff bases. J. Med. Chem. 1970, 13, 768–770. 10.1021/jm00298a054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek M. T.; Zabiszak M.; Nowak M.; Jastrzab R. Lanthanides: Schiff base complexes, applications in cancer diagnosis, therapy, and antibacterial activity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 370, 42–54. 10.1016/j.ccr.2018.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hodnett E. M.; Dunn W. J. Cobalt derivatives of Schiff bases of aliphatic amines as antitumor agents. J. Med. Chem. 1972, 15, 339. 10.1021/jm00273a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.-D.; Liao J.-P.; Huang S.-S.; Shen G.-L.; Yu R.-Q. Fluorescence Spectral Study of Interaction of Water-soluble Metal Complexes of Schiff-base and DNA. Anal. Sci. 2001, 17, 1031–1036. 10.2116/analsci.17.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L.; Cai P.; Feng Y.; Cheng J.; Xiang H.; Liu J.; Wu D.; Zhou X. Synthesis and photophysical properties of water-soluble sulfonato-Salen-type Schiff bases and their applications of fluorescence sensors for Cu2+ in water and living cells. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 735, 96–106. 10.1016/j.aca.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız M.; Demir N.; Ünver H.; Sahiner N. Synthesis, characterization, and application of a novel water-soluble polyethyleneimine-based Schiff base colorimetric chemosensor for metal cations and biological activity. Sens. Actuators, B 2017, 252, 55–61. 10.1016/j.snb.2017.05.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T.; Niu Q.; Li T.; Guo Z.; Liu H. A simple, reversible, colorimetric and water-soluble fluorescent chemosensor for the naked-eye detection of Cu2+ in ∼100% aqueous media and application to real samples. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2018, 188, 411–417. 10.1016/j.saa.2017.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno D.; Daier V.; Palopoli C.; Tuchagues J.-P.; Signorella S. Synthesis, characterization and antioxidant activity of water soluble MnIII complexes of sulphonato-substituted Schiff base ligands. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2010, 104, 496–502. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimerman Z.; Kiralj R.; Galić N. The structure and tautomeric properties of 2-(3-pyridylmethyliminomethyl) phenol. J. Mol. Struct. 1994, 323, 7–14. 10.1016/0022-2860(93)07972-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galić N.; Cimerman Z.; Tomišić V. Tautomeric and protonation equilibria of Schiff bases of salicylaldehyde with aminopyridines. Anal. Chim. Acta 1997, 343, 135–143. 10.1016/S0003-2670(96)00586-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayvalı M.; Hayvalı Z. The Synthesis of Some New Mono and bis (Crown Ether) s and Their Sodium Complexes. Tautomerism in o-Hydroxybenzo-15-crown-5 Schiff Bases as Studied by UV–VIS Spectrophotometry. Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem. 2004, 34, 713–732. 10.1081/SIM-120035952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barare B.; Yıldız M.; Alpaslan G.; Dilek N.; Ünver H.; Tadesse S.; Aslan K. Synthesis, characterization, theoretical calculations, DNA binding and colorimetric anion sensing applications of 1-[(E)-[(6-methoxy-1, 3-benzothiazol-2-yl) imino] methyl] naphthalen-2-ol. Sens. Actuators, B 2015, 215, 52–61. 10.1016/j.snb.2015.03.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barare B.; Yıldız M.; Ünver H.; Aslan K. Characterization and use of (E)-2-[(6-methoxybenzo [d] thiazol-2-ylimino) methyl] phenol as an anion sensor and a DNA-binding agent. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 537–542. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.12.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez M. R.; Del Plá J.; Piro O. E.; Echeverría G. A.; Espino G.; Pis-Diez R.; Parajón-Costa B. S.; González-Baró A. C. Structure, tautomerism, spectroscopic and DFT study of o-vanillin derived Schiff bases containing thiophene ring. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1165, 381–390. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.03.120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayvali Z.; Yardimci D. Synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of asymmetric Schiff bases derived from 4′-formylbenzo-15-crown-5 containing recognition sites for alkali and transition metal guest cations. Transition Met. Chem. 2008, 33, 421–429. 10.1007/s11243-008-9060-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rauf M.; Hisaindee S.; Saleh N. Spectroscopic studies of keto–enol tautomeric equilibrium of azo dyes. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 18097–18110. 10.1039/C4RA16184J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman D. S.; Smith R. A. 20 years of the Clean Water Act. Environment 1993, 35, 16. 10.1080/00139157.1993.9929068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 3rd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2004; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Liptak M. D.; Gross K. C.; Seybold P. G.; Feldgus S.; Shields G. C. Absolute p K a determinations for substituted phenols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 6421–6427. 10.1021/ja012474j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakmar T. P.; Franke R. R.; Khorana H. G. The role of the retinylidene Schiff base counterion in rhodopsin in determining wavelength absorbance and Schiff base pKa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1991, 88, 3079–3083. 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbalch K. A. The calculation of blood pH via the partition of carbon dioxide in plasma and oxygen binding of the blood as a function of plasma pH. Biochem. Z 1916, 78, 112–144. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Cheng J.; Ma X.; Zhou X.; Xiang H. Photophysical properties and pH sensing applications of luminescent salicylaldehyde derivatives. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2016, 42, 5027–5048. 10.1007/s11164-015-2343-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby G. A.; Demas J. N. Measurement of photoluminescence quantum yields. Review. J. Phys. Chem. 1971, 75, 991–1024. 10.1021/j100678a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A. T. R.; Winfield S. A.; Miller J. N. Relative fluorescence quantum yields using a computer-controlled luminescence spectrometer. Analyst 1983, 108, 1067–1071. 10.1039/an9830801067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Liao L.; Shen X.; He Y.; Xu C.; Xiao X.; Lin Y.; Nie C. A resonance light scattering method for the determination of uranium based on a water-soluble salophen and oxalate. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2014, 301, 863–869. 10.1007/s10967-014-3225-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.