Abstract

Background

The 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) guidelines have shifted focus from door‐to‐balloon (D2B) time to the time from first medical contact to device activation (contact‐to‐device time [C2D] ).

Hypothesis

This study investigates the impact of prehospital wireless electrocardiogram transmission (PHT) on reperfusion times to assess the impact of the new guidelines.

Methods

From January 2009 to December 2012, data were collected on STEMI patients who received percutaneous coronary interventions; 245 patients were included for analysis. The primary outcome was median C2D time in the PHT group and the secondary outcome was D2B time.

Results

Prehospital wireless electrocardiogram transmission was associated with reduced C2D times vs no PHT: 80 minutes (interquartile range [IQR], 64–94) vs 96 minutes (IQR, 79—118), respectively, P < 0.0001. The median D2B time was lower in the PHT group vs the no‐PHT group: 45 minutes (IQR, 34–56) vs 63 minutes (IQR, 49–81), respectively, P < 0.0001. Multivariate analysis showed PHT to be the strongest predictor of a C2D time of <90 minutes (odds ratio: 3.73, 95% confidence interval: 1.65‐8.39, P = 0.002). Female sex was negatively predictive of achieving a C2D time <90 minutes (odds ratio: 0.23, 95% confidence interval: 0.07‐0.73, P = 0.01).

Conclusions

In STEMI patients, PHT was associated with significantly reduced C2D and D2B times and was an independent predictor of achieving a target C2D time. As centers adapt to the new guidelines emphasizing C2D time, targeting a shorter D2B time (<50 minutes) is ideal to achieve a C2D time of <90 minutes.

Introduction

Rapid myocardial perfusion, either with fibrinolytic therapy or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is the standard of care in patients presenting with an ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). In patients treated for STEMI, longer times to reperfusion have been associated with higher mortality.1, 2 The time from hospital entry to reperfusion therapy, which includes aspiration thrombectomy and other interventions to restore coronary flow, for STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI is commonly referred to as door‐to‐balloon (D2B) time. This guideline measure has been incorporated as a publicly reported hospital performance measure by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Joint Commission, and should be within 90 minutes.3 In the 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association STEMI guidelines, the terminology and focus have changed; it is now recommended that time from first medical contact in the field to device activation (contact‐to‐device time [C2D]) be <90 minutes.4 It is unknown how feasible it is for STEMI centers to meet this new reperfusion time or what steps can be taken to reach a C2D time <90 minutes.

This study investigates the effect of implementing a strategy of prehospital wireless electrocardiogram (ECG) transmission (PHT) in patients with STEMI on C2D time at 2 STEMI centers as the primary outcome. The effect of PHT on D2B time was a secondary outcome. Another aim of the study was to identify clinical predictors for achieving C2D time <90 minutes.

Methods

Study Sample and Electrocardiographic Transmission

The study was conducted at Bellevue Hospital and New York University Langone Medical Center in New York, New York, both of which are major metropolitan centers capable of primary PCI for patients with STEMI. All New York City ambulances and paramedics are able to trigger STEMI notifications while en route to their receiving hospitals with a suspected STEMI. Specifically, newly designed Fire Department of New York ambulances are able to wirelessly transmit ECGs that are suspicious for STEMI from the field to a secure institution‐encrypted email address for viewing on a cardiologist's computer or handheld device at the same time as a STEMI notification is being sent to the receiving hospital. Other ambulances in the city do not have this capability. Whether or not the ambulance dispatched to a particular incident has this capability to wirelessly transmit ECGs is based solely on proximity to the emergency, access of the ambulance through traffic, and availability of the ambulance.

With PHT, cardiologists are able to confirm the ECG as a STEMI before the patient's arrival or deem the ECG not consistent with STEMI and not take the patient to the catheterization laboratory emergently. Prearrival demographic information is also sent to allow for preregistration of the patient in an effort to shorten triage time. Prehospital wireless ECG transmission can potentially shorten reperfusion times, as patients tend to bypass the emergency department at the receiving hospital and proceed directly to the catheterization laboratory. Without PHT, the evaluation of the patient begins in the emergency department.

Data Collection

From January 2009 to December 2012, data were collected prospectively on all STEMI patients who underwent PCI at Bellevue Hospital and New York University Langone Medical Center. Data regarding D2B time, patient demographics, baseline clinical presentation, admission ECG, medication administration, PCI characteristics, laboratory data, left ventricular ejection fraction within 72 hours by transthoracic echocardiogram or ventriculogram, and in‐hospital mortality were collected and reviewed. For C2D times, patient records were reviewed and the first documented contact time by paramedics on the emergency medical service (EMS) sheet was recorded. The difference between the first medical contact time and the hospital arrival time was added to the D2B time to calculate the C2D time.

A STEMI was defined as >1‐mm elevation of the ST segment in ≥2 contiguous leads on ECG, a new left bundle branch block with accompanying chest pain, or an anginal equivalent. All patients were discussed with an on‐call interventional cardiologist. To study a homogenous group of STEMI patients and limit confounders, those that did not meet CMS guidelines for reportable STEMI were excluded. The CMS guidelines exclude patients with nonprimary PCI, interhospital transfers, in‐hospital STEMI, cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, and/or documented reason for delay such as difficulty obtaining consent.3

All STEMI cases were reviewed by an interdisciplinary team of cardiologists, emergency medicine physicians, nursing leadership, telecommunication staff, and quality‐improvement personnel. All STEMI cases included in the final analysis were reviewed and verified by an American Board of Internal Medicine‐certified cardiologist.

Institutional review board approval at the participating institutions was obtained to carry out the study as described. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data‐capture tools.5 This is a secure, Web‐based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an interface for validated data entry, (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures, and (3) automated export procedures for data downloads.

Analytic Cohorts and Outcomes

Analyses were performed on STEMI patients with PHT vs patients without PHT (no PHT). The outcomes of interest were median C2D and D2B times in both the PHT and no‐PHT groups. In addition to evaluating C2D and D2B times as continuous variables, the goal C2D time was defined as <90 minutes.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics between the PHT and no‐PHT groups were compared using a 2‐sided t test for the continuous variables and a χ2 test for categorical variables. The distribution of continuous variables was examined using quantile‐quantile plots, histograms, and the Shapiro‐Wilk test of normality. Given that the distribution of continuous variables deviated significantly from normality, the Wilcoxon signed‐rank test was utilized to compare the difference between the PHT and no‐PHT groups for both C2D and D2B times.

To identify clinical predictors of C2D times <90 minutes, univariate analysis was performed on all prehospital baseline characteristics. Prehospital characteristics that yielded P values <0.15 via univariate analysis were used in a multivariate model to more rigorously weigh their impact on reaching target C2D times <90 minutes. Univariate analysis was also performed on all prehospital baseline characteristics to identify clinical predictors of D2B times <90 minutes.

In addition, correlation between C2D and D2B times was performed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. To explore the interaction between these 2 variables, linear regression analysis was performed and a curve of best fit was drawn to approximate the relationship. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. The SAS software for Windows, version 9.3, was used for statistical computation (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC).

Results

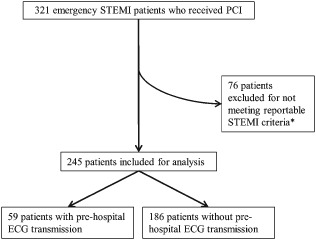

From January 2009 to December 2012, there were 321 STEMI patients that underwent PCI. Of these, 23.7% were excluded for not meeting reportable STEMI criteria, as follows: 7.5% had been transferred from another facility or were in‐hospital STEMIs; 7.2% presented with a cardiac arrest, which required further medical evaluation before cardiac catheterization; 5% were in shock or had severe hemodynamic instability, requiring stabilization prior to PCI; and 4% had difficult vascular access secondary to peripheral vascular disease or congenital anomalous coronary arteries. In total, 245 patients were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Approximately 25% of the patients arrived with PHT in the final cohort.

Figure 1.

Patient flow for primary analysis including the total number of patients with STEMI who received PCI. *Guidelines for a nonreportable STEMI included nonprimary PCI, interhospital transfer, in‐hospital STEMI, cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, or documented reason for delay such as difficulty obtaining consent. Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Baseline characteristics of the 245 patients included in the final analysis are shown in Table 1. Preadmission cardiovascular risk factors, outpatient medication profile, and physiological admission data were analyzed and found to be similar between groups. The patients were largely middle‐aged white men with similar cardiac risk factors. Overall, most of the STEMIs were anterior STEMIs (41%) with PCI to the left anterior descending artery. The in‐hospital mortality rate was 0% in the PHT group and 2.2% in the no‐PHT group (P = 0.58). The median left ventricular ejection fraction was 43% in the PHT group vs 45% in the no‐PHT group (P = 0.18).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| PHT, n = 59 | No PHT, n = 186 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 56.8 ± 11.1 | 59.9 ± 13.3 | 0.08 |

| Male sex, % | 88 | 83 | 0.33 |

| Ethnicity, % | |||

| Caucasian, non‐Hispanic | 44.1 | 55.4 | 0.45 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | 11.9 | 7.5 | 0.36 |

| Hispanic | 13.6 | 16.7 | 0.72 |

| East Asian | 6.8 | 3.8 | 0.42 |

| South Asian | 8.5 | 7.5 | 0.44 |

| Other | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.64 |

| Risk factors, % | |||

| DM | 13.6 | 21.0 | 0.19 |

| Hypertension | 49.2 | 54.3 | 0.49 |

| Active smoker | 28.8 | 22.6 | 0.33 |

| CAD history | 6.8 | 16.1 | 0.07 |

| Surgical bypass history | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.00 |

| PCI history | 5.1 | 12.9 | 0.10 |

| Outpatient medication, % | |||

| ASA | 18.6 | 24.7 | 0.33 |

| Thienopyridine | 1.7 | 4.3 | 0.69 |

| β‐Blocker | 10.2 | 16.7 | 0.21 |

| Statin | 20.3 | 28.0 | 0.24 |

| ACEI or ARB | 13.6 | 22.6 | 0.13 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Negative admission TnI, % | 35.6 | 41.4 | 0.43 |

| % peak TnI ≥50 ng/mL | 66.1 | 63.4 | 0.11 |

| LDL‐C, mg/dL (IQR) | 112 (91–142) | 115 (92–140) | 0.53 |

| Hg, g/dL (IQR) | 14.8 (13.9–15.4) | 14.7 (13.7–15.6) | 0.41 |

| Cr, mg/dL (IQR) | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.55 |

| Admission information | |||

| SBP, mm Hg (IQR) | 135 (121–150) | 138 (120–153) | 0.67 |

| Heart rate, bpm (IQR) | 80 (66–90) | 78 (65–89) | 0.59 |

| Anterior ST elevations, % | 47.5 | 39.2 | 0.26 |

| Cardiac catheterization data | |||

| PCI location, % | |||

| LM artery | 2 | 0 | 0.24 |

| LAD artery | 49 | 39 | 0.18 |

| LVEF, % (IQR) | 43 (35–50) | 45 (35–55) | 0.18 |

| Outcomes | |||

| In‐hospital death, % | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.58 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASA, aspirin; CAD, coronary artery disease; Cr, creatinine; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG, electrocardiogram; Hg, hemoglobin; IQR, interquartile range; LAD, left anterior descending; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LM, left main; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; no PHT, no prehospital transmission of ECG; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PHT, prehospital transmission of ECG; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TnI, troponin I.

Outcomes

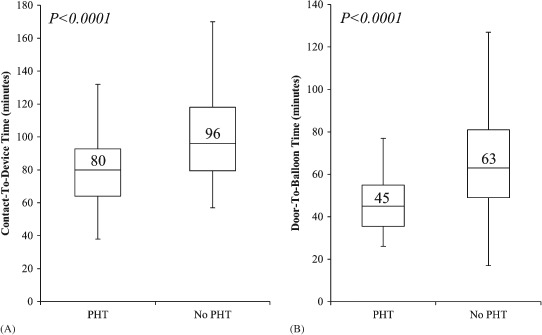

The primary outcome of median C2D time was lower in the PHT group at 80 minutes (interquartile range [IQR], 64–94) vs 96 minutes (IQR, 79–118) in the no‐PHT group, P < 0.0001 (Figure 2A). The median D2B time was also lower in the PHT group: 45 minutes (IQR, 34–56) compared with 63 minutes (IQR, 49–81) in the no‐PHT group, P < 0.0001 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Outcomes. (A) Median C2D times with IQRs of patients with prehospital transmission of ECG vs patients with no prehospital transmission of ECG. (B) Median D2B times with IQRs of patients with prehospital transmission of ECG vs patients with no prehospital transmission of ECG. Abbreviations: C2D, contact‐to‐device; D2B, door‐to‐balloon; ECG, electrocardiogram; IQR, interquartile range; no PHT, no prehospital transmission of ECG; PHT, prehospital transmission of ECG.

Predictors of Achieving Device Time Goals

In the univariate model, PHT was the strongest predictor of C2D time <90 minutes (odds ratio [OR]: 3.60, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.70‐7.59, P = 0.0008; Table 2). Of note, female sex was negatively associated with reaching C2D time <90 minutes (OR: 0.22, 95% CI: 0.08‐0.59, P = 0.003; Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate Predictors of Achieving C2D Time <90 Minutes

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHT | 3.60 | 1.70‐7.59 | 0.0008 |

| DM | 0.84 | 0.35‐2.02 | 0.69 |

| Hypertension | 1.89 | 0.98‐3.73 | 0.07 |

| CAD | 0.38 | 0.12‐1.19 | 0.10 |

| Prior PCI | 1.52 | 0.42‐5.45 | 0.52 |

| Cr | 0.99 | 0.24‐4.08 | 0.98 |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.95‐1.00 | 0.07 |

| Female sex | 0.22 | 0.08‐0.59 | 0.003 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 0.83 | 0.43‐1.63 | 0.59 |

| Hispanic | 0.59 | 0.23‐1.53 | 0.28 |

| Black | 1.53 | 0.47‐4.95 | 0.48 |

| Asian | 0.85 | 0.31‐2.36 | 0.75 |

| Smoking | 0.56 | 0.26‐1.18 | 0.12 |

Abbreviations: C2D, contact‐to‐device; CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; Cr, creatinine; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG, electrocardiogram; OR, odds ratio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PHT, prehospital transmission of ECG.

In the univariate analysis, the clinical predictors that either were statistically significant or approached statistical significance with a P value <0.15 were PHT, hypertension, coronary artery disease, age, sex, and smoking (Table 2). In a multivariate analysis using the aforementioned 6 variables, PHT remained the strongest independent predictor for a C2D time <90 minutes (OR: 3.73, 95% CI: 1.65‐8.39, P = 0.002). Using multivariate analysis, female sex was still negatively predictive of reaching C2D time <90 minutes (OR: 0.23, 95% CI: 0.07‐0.73, P = 0.01).

In the univariate analysis for D2B time, PHT was also the strongest predictor of reaching a D2B time <90 minutes (OR: 21.40, 95% CI: 1.29‐356.10, P = 0.002). Female sex did not impact odds of reaching D2B time <90 minutes (OR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.20‐1.32, P = 0.17).

Contact‐to‐Device and Door‐to‐Balloon Times

Contact‐to‐device time was plotted vs D2B time to assess the impact of prehospital transport times on C2D times, and to investigate how well correlated D2B and C2D times were. There was a strong correlation between C2D and D2B times (Pearson r = 0.90, P < 0.0001). Using linear regression analysis, the equation of the best‐fit curve was C2D = 1.02 (D2B) + 36.76. A D2B time <60 minutes had a positive predictive value of 80% for achieving a C2D time <90 minutes. Seventy‐three percent of patients with PHT had C2D times <90 minutes, whereas only 60% of patients without PHT were within this goal. One hundred percent of patients with PHT had D2B times <90 minutes, whereas 85% of patients without PHT were able to meet this standard.

Discussion

Prehospital Transmission of Electrocardiogram and Reperfusion Times

After careful analysis of C2D and D2B times, it is evident that the rapid, secure, electronic transmission of the field ECG in a potential STEMI to the receiving cardiologist most effectively reduces C2D and D2B times in a highly populated city such as New York City. Regardless of population, traffic congestion, or location, PHT significantly reduces D2B times in STEMI patients. These results are consistent with the other studies located in New Jersey and suburban North Carolina with regard to D2B.6, 7, 8 This is the first study to date that shows PHT also effectively reduces C2D time in STEMI patients.

Predictors of Achieving Target Times

In univariate and multivariate analyses, PHT is an independent predictor of C2D time <90 minutes. To reduce C2D time in patients, STEMI centers must reduce D2B times and also the times from first medical contact to the door. From this analysis, PHT is one method that can reduce C2D time, but it is prudent that STEMI centers continue to work with EMS personnel to shorten triage and transport times to STEMI centers.

In their efforts to improve reaching target D2B times, the American College of Cardiology and various partner organizations launched the D2B Alliance in 2006 with the goal of achieving a D2B within 90 minutes for ≥75 percent of nontransfer patients undergoing primary PCI.9 Since the launch, hospitals have been exceeding this benchmark with D2B times approaching 60 minutes.10 The present study assessed the impact of PHT on C2D and D2B times in patients presenting with STEMI and showed that PHT was a strong independent predictor of achieving optimal treatment times. In addition, given the recent shift in focus from D2B time to C2D time, this study offers insights into the correlation between the 2 measures. Using the equation from the regression analysis in this study to achieve a C2D time <90 minutes, D2B time now has to approach 50 minutes.

Emergency Health Care Costs

Utilizing PHT in STEMI patients to achieve C2D <90 minutes can potentially reduce health care costs.11 Brunetti et al report that in 629 patients with a prehospital diagnosis of STEMI, PHT can potentially save 69 lives per year.11 In this region of Italy, using PHT can save approximately €892 000 to €4 219 000 per year and the cost per quality‐adjusted life‐year gained is €1927.11 The United States spends about 16% of its gross domestic product on health care costs. Some economic models have estimated the lifetime cost of nonfatal myocardial infarction to be up to $55 400.12, 13 Given the current economic climate and the ongoing discussions about making health care more affordable and available, every step of a STEMI patient's care is being evaluated for efficiency and optimal utilization. Quality‐improvement initiatives resulting in reduction of reperfusion times have shown mortality benefit, reduction in length of stay, and recently have been shown to reduce overall direct inpatient costs.1, 14, 15, 16, 17

Female STEMI Patients

Studies have demonstrated that women tend have longer D2B times than men.18, 19, 20, 21 Unadjusted retrospective subgroup analysis in one study noted the increase in D2B and C2D times in women vs men.19 In this study, gender did not seem to impact D2B, but a similar gender disparity was noted such that women had lower odds of achieving optimal C2D times when compared with men. A possible explanation could be that women can manifest symptoms of CAD differently when compared with men.22 Angina in women can manifest as atypical chest pain or dyspnea.22 The prevalence of CAD is also less in women than in men, and women are more likely to present with unstable angina than STEMI when compared with men.22 Because of the prevalence of STEMI and atypical presentation of angina in women, there may be a bias toward treatment of female STEMI patients that may explain the increased C2D time; however, this needs to be more systematically studied.

Study Limitations

This study evaluated the hospital systems of 2 New York City hospitals with regard to their care of emergency STEMI patients. Data were collected prospectively with regard to D2B times, but there was retrospective collection of data to compute C2D times. Retrospective data collection carries with it hidden biases, which is a limitation of the C2D analysis. Although baseline characteristics were similar, this trial is a nonrandomized analysis in which unmeasured factors could have possibly confounded the results. Future prospective randomized trials with regard to PHT seem impractical, given its impact on reperfusion times that has been borne out in previous studies.6, 7, 8

Because of differences in EMS protocols, traffic congestion, and hospital systems, these results have to be generalized with caution. The study was not designed to demonstrate a difference in mortality in STEMI patients, nor was it designed to detect differences in subgroups, such as gender. In this study, 16% of the patients were female, making it difficult to draw conclusions about the impact of gender on C2D times. A dedicated prospective study to evaluate female patients is warranted to better understand the effect of gender on C2D times.

Conclusion

ST‐elevation myocardial infarction patients with PHT had shorter C2D and D2B times. This strategy appears essential to achieve C2D <90 minutes. Instead of D2B targets of <90 minutes, or <60 minutes, results from this study suggest that hospitals should strive to achieve a D2B <50 minutes to meet the target C2D time of <90 minutes. Based on the results from this analysis, future research should focus on the impact of reducing C2D time on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Overall, the implementation of a wireless system similar to the one described here for all emergency STEMI centers would help reduce both C2D and D2B times.

Data analysis and statistical support was provided by New York University School of Medicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Group.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. McNamara RL, Wang Y, Herrin J, et al; NRMI Investigators. Effect of door‐to‐balloon time on mortality in patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2180–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rathore SS, Curtis JP, Chen J, et al; National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Association of door‐to‐balloon time and mortality in patients admitted to hospital with ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: national cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. QualityNet . Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures. http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?pagename=QnetPublic/Page/QnetTier2&cid=1141662756099. Accessed January 10, 2012.

- 4. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al; ACCF/AHA Task Force. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:529–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanchez‐Ross M, Oghlakian G, Maher J, et al. The STAT‐MI (ST‐Segment Analysis Using Wireless Technology in Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial improves outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:222–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adams GL, Campbell PT, Adams JM, et al. Effectiveness of prehospital wireless transmission of electrocardiograms to a cardiologist via hand‐held device for patients with acute myocardial infarction (from the Timely Intervention in Myocardial Emergency, NorthEast Experience [TIME‐NE]). Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1160–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dhruva VN, Abdelhadi SI, Anis A, et al. ST‐Segment Analysis Using Wireless Technology in Acute Myocardial Infarction (STAT‐MI) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:509–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krumholz HM, Bradley EH, Nallamothu BK, et al. A campaign to improve the timeliness of primary percutaneous coronary intervention: Door‐to‐Balloon: An Alliance for Quality. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rokos IC, French WJ, Koenig WJ, et al. Integration of prehospital electrocardiograms and ST‐elevation myocardial infarction receiving center (SRC) networks: impact on door‐to‐balloon times across 10 independent regions. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brunetti ND, Dellegrottaglie G, Lopriore C, et al. Prehospital telemedicine electrocardiogram triage for a regional public emergency medical service: is it worth it? A preliminary cost analysis; Clin Cardiol. 2014; doi: 10.1002/clc.22234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Sullivan AK, Rubin J, Nyambose J, et al. Cost estimation of cardiovascular disease events in the U.S. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29:693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization . World health statistics 2009. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Fact sheet no. 290. http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2009/en. Accessed March 25, 2012.

- 14. Gibson CM, Pride YB, Frederick PD, et al. Trends in reperfusion strategies, door‐to‐needle and door‐to‐balloon times, and in‐hospital mortality among patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction enrolled in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J. 2008;156:1035–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parikh R, Faillace R, Hamdan A, et al. An emergency physician–activated protocol, 'Code STEMI' reduces door‐to‐balloon time and length of stay of patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khot UN, Johnson‐Wood ML, Geddes JB, et al. Financial impact of reducing door‐to‐balloon time in ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: a single‐hospital experience. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Darling CE, Smith CS, Sun JE, et al. Cost reductions associated with a quality‐improvement initiative for patients with ST‐elevation myocardial infarction. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chiriboga DE, Yarzebski J, Goldberg RJ, et al. A community‐wide perspective of gender differences and temporal trends in the use of diagnostic and revascularization procedures for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1993;71:268–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rezaee ME, Brown JR, Conley SM, et al. Sex disparities in pre‐hospital and hospital treatment of ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Hosp Pract (1995). 2013;41:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bangalore S, Fonarow GC, Peterson ED, et al; Get With the Guidelines Steering Committee and Investigators. Age and gender differences in quality of care and outcomes for patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2012;125:1000–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jneid H, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, et al; Get With the Guidelines Steering Committee and Investigators. Sex differences in medical care and early death after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;118:2803–2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Collins SD, Ahmad S, Waksman R. Percutaneous revascularization in women with coronary artery disease: we've come so far, yet have so far to go. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;20:436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]