Abstract

Implantable cardiac devices, including defibrillators and pacemakers, may be the cause of tricuspid regurgitation (TR) or may worsen existing TR. This review of the literature suggests that TR usually occurs over time after lead implantation. Diagnosis by clinical exam and 2‐dimensional echocardiography may be augmented by 3‐dimensional echocardiography and/or computed tomography. The mechanism may be mechanical perforation or laceration of leaflets, scarring and restriction of leaflets, or asynchronized activation of the right ventricle. Pacemaker‐related TR might cause severe right‐sided heart failure, but data regarding associated mortality are lacking. This comprehensive review summarizes the data regarding incidence, mechanism, and treatment of lead‐related TR.

Introduction

Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) is a common valvular lesion, with 1.6 million people in the United States affected by moderate or severe TR.1 The pathophysiology is divided into 2 major categories: functional (associated with left or right heart pathology) and structural (from primary leaflet abnormalities). Functional tricuspid regurgitation often results from left‐sided heart valve disease.1 The incidence of TR may be increasing in frequency coincident with the use of implanted cardiac devices, such as implantable cardioverter‐defibrillators (ICDs) and permanent pacemakers (PPMs). This association was first described by Gibson and colleagues in 1980.2 The current literature regarding symptomatic, lead‐related TR following ICD or PPM is based mainly on case reports and observational studies.3 In this article, we provide a comprehensive review of the incidence, diagnosis, mechanism, and outcomes of TR in patients with cardiac devices.

Incidence

The prevalence of TR is between 25% to 29% of patients with PPM, compared to 12% to 13% in the control group (P < 0.05).4, 5 Numerous authors have found worsening of preexisting TR by 1 or 2 grades in 11% to 25% of patients, over a period of 1 to 827 days after PPM or ICD placement 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 (Table 1). Tricuspid regurgitation may worsen, or new TR may develop after up to 7 years of device implantation.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Table 1.

Studies Assessing Prevalence of Lead‐Related TR in Patients With PPM or ICD

| Author of Study | No. of Patients | Median Age, y | ICD, % | Preprocedure Echo (Average Timing) | Postprocedure Echo (Average Timing) | Increase in Prevalence of TR by at Least 1 Grade, % | Statistical Significance of Difference in Prevalence (P Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Cock et al5 | 48 | 62 | 0 | No | Yes (7.4 years) | 16a | <0.05 |

| Paniagua et al4 | 745b | 77.5 | 0 | No | Yes (unknown) | 13 | <0.001 |

| Leibowitz et al9 | 35 | 67 | 57 | Yes (4.5 days) | Yes (1.2 days) | 11 | Unknown |

| Kucukarslan et al8 | 61 | 53 | 10 | Yes (3 days) | Yes (1 day) | 13 | Unknown |

| Webster et al7 | 123 | 16 | 55 | Yes (unknown) | Yes (242 days and 827 days) | 25c | <0.05 |

| Kim et al10 | 248 | 75.4 | 30 | Yes (7 days) | Yes (93 days) | 24 | <0.05 |

| Klutstein et al6 | 410 | 72‐77 | 0 | Yes (75 days) | Yes (113 days) | 18 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator; PPM, permanent pacemaker; TR, tricuspid regurgitation.

Unknown grade.

Paniagua et al. studied 374 patients but the prevalence of TR in the PPM group was reported out of the 745 patients. cAt second postimplantation echocardiogram.

Evidence Supporting an Increase in TR After Cardiac Device Implantation

Paniagua and colleagues retrospectively evaluated 374 patients who were studied with echocardiography after pacemaker implantation, and reported an increase in the prevalence of moderate–severe TR (25% vs 12%, odds ratio [OR]: 4.75).4 De Cock and colleagues prospectively compared 48 patients with PPM, followed them over a mean of 7.4 years, with age‐matched controls without PPM. The prevalence of TR was 29% compared to 13.5% in the control group (P < 0.05).5 However, they did not look at preimplantation tricuspid valve function.

Kim and colleagues studied 248 patients with either an ICD or PPM, with pre‐ and postimplantation echocardiograms.10 Tricuspid regurgitation, based on jet area by color Doppler, worsened by at least 1 grade in 24.2% of patients (P = 0.048). The average TR grade increased by 0.15 ± 0.8 (P = 0.004) in the entire population. Clinically significant TR of grades 1.5 to 3 were found in 21.2% of patients who had no clinically significant TR prior to lead insertion, 5% of which was moderate–severe to severe. Interestingly, regurgitation was more common in patients with ICDs compared to PPM (32.4% vs 20.7%, P = 0.048), which may result from thicker or more rigid leads or from the additional exposed metal shocking coil that could cause more fibrosis.

Klutstein and colleagues studied 410 patients with PPM, with less than moderate TR at baseline, finding that TR worsened by >2 grades in 18.3% of the patients (P < 0.001) after a median of 113 days (range, 1–3549 days). Interestingly, TR improved by ≥ 2 grades in 4.4% of patients.6

Webster and colleagues studied 123 pediatric patients (median age, 16 years), each with preimplantation and 2 follow‐up echocardiograms postimplantation (first after a mean of 242 days, second after a mean of 827 days).7 They did not find evidence of worsening of TR based on echocardiograms performed <1 year after implantation. However, TR did progress from a mean of grade 1.54 to 1.69 (P < 0.02) over 2 years. Tricuspid regurgitation developed or worsened by at least 1 grade in 22% of patients and by 2 grades in 3% of patients, whereas 63% who had no change in their tricuspid valve function and 12% had improvement in existing TR.

Evidence Against Worsening of TR

On the other hand, evidence against worsening of TR is limited. Other investigators have illustrated that TR does not worsen acutely after cardiac device implantation, but may develop or worsen later in the chronic phase.7, 8, 9, 11 Kucukarslan and colleagues evaluated 61 patients with either ICD or PPM, of whom 49% had TR prior to cardiac device implantation.8 The study reported an increase from normal/trivial to mild in 5 patients (16%) and an increase from mild to moderate in 3 patients (10%), with no patients showing an increase from moderate to severe TR. In their subjective assessment, new or worsening TR was considered rare, and therefore argued against deterioration acutely or after 6 months. Leibowitz and colleagues found no significant change in TR grade acutely in 35 patients with ICD or pacemakers. Unexpectedly, 6 patients had improvement in their TR after lead implantation, possibly related to the improved hemodynamics and decreased right ventricular pressure.9

Morgan and colleagues assessed the incidence of TR 6 months after PPM implantation in 20 patients who had undergone saline‐contrast echocardiography. By assessing inferior vena cava contrast reflux during systole as a marker for TR, they found no significant occurrence of TR after device implantation.12 Two major limitations of their study were the lack of comparison with preimplantation echocardiograms, and the use of a nonstandardized method to detect the presence of TR.13

Unfortunately, many studies assessing the incidence of TR after device placement are fraught with limitations based on retrospective and uncontrolled evidence, and variability in the diagnostic criteria used. Nevertheless, many of the larger studies have demonstrated worsening in TR later after several years of implantation, with some suggestion of acute worsening of TR in a small number of patients.

Predictors of TR After Device Implantation

The predictors of developing TR after cardiac device implantation are not well understood. Investigations of adult population have found that advanced age is a risk factor for developing TR (age range, 72–75 years),6 whereas the pediatric study mentioned previously (age range, 2–52 years) did not find age to be a factor.7

Placement of more than 1 lead also may or may not worsen TR, with conflicting data in the literature (Table 2). Celiker and colleagues assessed TR after each of 2 pacemaker leads was implanted in 40 patients, and after a single ventricular lead was implanted in 22 patients, finding no difference in mild to moderate TR among the 2 groups (83% vs. 77%). However, 1 of the main limitations of the study is the absence of echocardiographic assessment of the tricuspid valve prior to lead implantation.14

Table 2.

Studies Assessing the Prevalence of Pacemaker Lead‐Related TR in Patients With 1 Ventricular Lead vs 2 Leads

| Author of Study | No. of Patients | Median Age, y | ICD, % | Preprocedure Echo | Postprocedure Echo (Average Timing) | Prevalence of TR (Grade), % | Statistically Significant Difference Between the Groups With 1 and 2 Leads (P Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Celiker et al14 | |||||||

| 1‐lead group | 22 | 69 | 0 | No | Yes (2433 days) | 18.2 (moderate), 59.1 (mild) | NS |

| 2‐lead group | 18 | 67 | 0 | No | Yes (1186 days) | 22.2 (moderate), 61.1 (mild) | |

| Postaci et al15 | |||||||

| 1‐lead group | 32 | 61 | 0 | No | Yes (2 years) | 9.4 (grade 2) | <0.05 |

| 2‐lead group | 18 | 61 | 0 | No | Yes (2 years) | 55.6 (grade 2) |

Abbreviations: ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator; NS, not significant; TR, tricuspid regurgitation.

On the other hand, Postaci and colleagues found that patients with 2 device leads have more grade 3 TR, present in 55.6% of patients with 2 ventricular leads, compared to 9.4% in those with 1 lead (P < 0.05).15 In the pediatric population, it was found that a risk factor for lead‐related TR was congenital heart disease that is not right sided.7

Clinical Presentation

Patients may present with clinical symptoms of right‐sided congestive heart failure; however, many are asymptomatic even when TR is present. Physical examination may reveal the typical respirophasic systolic murmur at the left sternal border that increases with inspiration, but in many the murmur is unimpressive. Rahko describes only a 28% prevalence of a regurgitant murmur in echocardiographically detected TR.16 The classic physical exam would be right‐sided findings (jugular venous distention, pulsatile liver, peripheral edema) without left‐sided findings.17, 18

The TR murmurs that increase with inspiration are different than TR murmurs related to congestive heart failure, which usually diminish with inspiration. This murmur that gets louder with inspiration is Carvallo's maneuver, which has a specificity of 100% and a sensitivity of 80%.19 Other physical exam findings typical of TR include hepatojugular reflux (specificity and sensitivity of 100% and 66%, respectively, in detecting TR).19 The right atrial V wave is highly sensitive but not specific in detecting the presence and the severity of TR.20

Imaging Diagnosis

Both 2‐dimensional (2D) echocardiography and color Doppler flow mapping are essential in diagnosing TR. The severity is based on the direction and the size of the regurgitant jet, the presence of proximal flow convergence, and vena contracta width.21 The sensitivity and specificity of classifying TR as severe using vena contracta width ≥6.5 mm is 88.5% and 93.3%, respectively.22

The diagnosis of TR may be underestimated by 2D echocardiography. It is difficult to appreciate the full anatomical relationship between the tricuspid valve and the ICD or PPM lead(s), as only 2 leaflets are visible simultaneously when using any 2D imaging plane.3, 23 Furthermore, the posterior leaflet, which is implicated in many PPM lead‐related TR cases, is only visualized in some views, and is less commonly imaged during the routine echocardiographic examination.23

The PPM lead may become entrapped in the thickened, fibrotic, and fused posterior and septal leaflets.23 Three‐dimensional (3D) transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) maybe useful in diagnosing lead‐related TR, particularly in visualizing the short axis of the tricuspid valve, not obtainable with 2D echocardiography, which allows assessment of the route and the position of the lead within the tricuspid valve apparatus.3, 18, 23 Unfortunately, due to the need for dedicated probes and image analysis software, as well as greater cost, 3D echocardiography is not as widely used currently.

In their review of more than 1000 patients undergoing tricuspid valve replacement, Lin and colleagues found 41 patients whose significant TR was due to PPM or ICD leads, based on operative findings of leaflet damage. Interestingly, the TR was severe in only 63% of those 41 patients. One significant limitation to visualizing TR on TTE is that the shadow created by the pacemaker wires may lead to suboptimal visualization of the regurgitant jet. Therefore, the clinical examination and the large V waves in the jugular venous pulse contour are important.17

Other evolving methods include contrast‐enhanced multidetector computed tomography, which may be used indirectly to detect and grade TR based on early opacification of hepatic veins or inferior vena cava during first‐pass intravenous contrast enhancement. This method has a sensitivity of 90.4% and a specificity of 100% in detecting echocardiographic TR.1, 24

Another modality is cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), which can be used to both detect and quantify TR based on regurgitant jet area and volume, with a sensitivity and specificity of 88% and 94%, respectively, compared to right ventricular angiography. However, most pacemaker devices and leads are not compatible with CMR.25

Mechanism

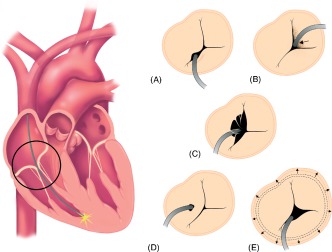

Tricuspid regurgitation after lead placement can occur via multiple mechanisms (Figure 1). It may be the result of mechanical causes such as scar formation or thrombus on the leads impairing closure. Perforation or laceration of valve leaflets is another cause of TR. Another mechanism is asynchrony, resulting from abnormal right ventricle (RV) activation from a pacemaker. This may resolve if the patient returns to his/her intrinsic rhythm.23, 26, 27 Kim and colleagues demonstrated that TR after ICD or PPM implantation is not related to an increase in pulmonary artery pressure.10

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of mechanical tricuspid regurgitation in the setting of permanent pacemaker or implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator leads. (a) Valve obstruction caused by lead placed in between leaflets. (b) Lead adherence due to fibrosis and scar formation to valve causing incomplete closure. (c) Lead entrapment in the tricuspid valve apparatus. (d) Valve perforation or laceration. (e) Annular dilatation.

Early postmortem investigations in the 1970s demonstrated that pacemaker leads can adhere to the tricuspid valve leaflets, and even more commonly to the papillary muscles.2 Leaflet perforation or lacerations are most commonly noted at the posterior leaflet. In TR that develops years after PPM implantation, Iskandar and colleagues posit that adhesion of the tricuspid valve (TV) leaflet to the pacer lead results in restricted movement and therefore abnormal coaptation of the posterior leaflet with the septal and anterior leaflets.26

As early as 12 hours postprocedure, there is neoendocardium formation, with development of fibrous sheaths around the electrode, resulting in multiple endocardial attachments, fibrosis, and adhesion that may affect the TV function. A thin fibrin layer starts developing around the wire soon after lead implantation. Thrombosis and edema of the valve tissue may also occur 4 to 5 days after implantation. A study by Huang and colleagues found that thrombosis on the lead often occurs within 4 to 5 days after implantation.28 This may or may not result in acute TR. As described previously, the frequency of acute TR varies in the many published studies.7, 8, 9, 11

Leads that are positioned directly on the annulus, or in the commissure between leaflets, may lead to obstruction of valve closure and a progression of TR. Seo and colleagues demonstrated that the majority of lead‐related TR occurs when the leads are placed between the posterior and septal leaflets.3 Moreover, 7 out of 12 patients with severe TR had their leads obstructing the closure of the valve either on the posterior or the septal leaflet. In contrast, a study of 86 patients by Krupa and colleagues did not show any dominant lead topography in patients who develop TR after either ICD or PPM.29

Lin and colleagues found that the mechanism of TR after pacemaker implantation in 41 patients was lead impingement in 39%, lead adherence in 34%, lead perforation in 17%, and lead entanglement in 39%.17

Other less‐common causes of lead‐related TR are tricuspid annular dilatation, perforation, and laceration of leaflets by the leads.3, 17, 27 Novak and colleagues, based on their postmortem study, showed that out of the 78 single ventricular leads, 11 leads (14%) were fixed by fibrous tissues to the tricuspid orifice, and 25 leads (32%) penetrated through the chordae tendineae of the tricuspid valve.30

Another uncommon mechanism is the occurrence of TR after other valvular interventions. Loupy and colleagues reported the case of a severe TR 17 years after original PPM implantation, 9 years after placement of a second ventricular lead, and 1 month after aortic valve replacement (AVR).31 The authors suggest that the AVR may have led to conformational changes between the tricuspid valve and the pacemaker leads.

Management and Prognosis

Medical Management

Medical treatment has been studied mostly in patients with functional TR, and includes treating the underlying cause and congestive heart failure management.1 There is a paucity of data about the outcomes of lead‐related TR managed medically. Aggressive volume management using diuretics may be beneficial.

Lead(s) Extraction

Chronically implanted leads may cause fibrosis and scar tissue formation, resulting in adherence to the tricuspid valve. Device‐related infection is the main cause for lead extraction.32 Lead extraction has become both increasingly sophisticated and specialized. Sometimes leads can be removed by simple traction. Some patients require advanced techniques using stylets and laser‐equipped sheaths. Percutaneous removal of PPM and ICD leads is often performed in large specialty centers with significant experience, but carries with it significant and sometimes fatal risk.18 Rickard and Wilkoff32 reported an incidence of major complications after lead extraction (death, cardiac or vascular avulsion requiring intervention, pulmonary embolism requiring surgical intervention, respiratory distress, stroke, or pacing system‐related infection) of 1.6% among patients seen between 1994 and 1999. However, in the last decade, the success rate has been 95% to 97%, and the complication rate is down to 0.4% to 1%.

Consequently, the extraction procedure may itself lead to worsening TR.18, 23, 33 The major risk factors for developing TR after extraction are the use of a laser sheath (OR: 10.17, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.16‐94.74, P = 0.001) or any additional tools for extraction beyond simple traction (OR: 8.96, 95% CI: 2.02‐81.45, P = 0.001), extraction of more than 2 leads (OR: 4.67, 95% CI: 1.38‐14.48, P = 0.003), female patients (OR: 3.36, 95% CI: 1.14‐9.90, P = 0.01), and patients with longer duration of implantation.34 Franceschi and colleagues reported no statistically significant increase in mortality in those who develop TR postextraction (31.6%) vs those who do not develop TR postextraction (13.7%) (P = 0.26).34 TR is more likely to occur after PPM extraction than ICD lead extraction, but this may be from a longer duration of implantation or more fibrous tissues deposition and adherence to the tricuspid valve.33

Surgical Treatment

TR is usually treated by either surgical repair (usually consisting of ring annuloplasty) or by tricuspid replacement in some patients with advanced valvular disease. Currently, percutaneous tricuspid repair remains experimental and is under study using animal models. It is estimated that 8000 surgical tricuspid repairs occur annually. The majority of these cases involve patients without device‐related TV pathology. The success rate of tricuspid valve repair is generally reported to be 85%, although recurrence of TR is common.1 Tricuspid valve replacement is associated with a 6%, 30‐day operative mortality, and 8% in‐hospital mortality.11, 23, 26 The 10‐year survival for patients undergoing tricuspid valve replacement in conjunction with left‐sided heart valve surgery is 78% and drops to 41% in patients with triple valve surgery, as compared to the 10‐year survival rate after AVR (65%), mitral valve replacement (MVR) (55%), and combined AVR and MVR (55%).1, 35

There are limited data about surgical treatment in patients with lead‐related TR. In the study above by Lin and colleagues, the average time to surgery was 72 months after device implantation, arguing that severe lead‐related TR is likely to occur over a longer time frame, and the majority of patients showed significant improvement postoperatively.17

There are not enough data assessing mortality in patients with lead‐related TR to make any firm conclusion about their benefits from surgery. In particular, long‐term durability of surgery remains unknown. Baman and colleagues studied patients with cardiac‐device infection and reported 18% all‐cause mortality after 6 months of infection. The majority of their patients had their devices extracted either percutaneously (81%) or surgically (8%), whereas 11% had medical management only. Moderate to severe TR was identified as an independent variable associated with higher mortality (hazard ratio: 4.24, 95% CI: 1.84‐9.75, P ≤ 0.01).36

Prevention

Data are limited when it comes to preventing TR while placing ICDs or PPM leads. Few data exist on the type of leads, the technique used and the locations of the leads that may be associated with less TR. Lin and colleagues, in their study of patients who had lead‐related TR, found that the majority of the leads were silicone (74%) compared to polyurethane (26%).17 However, the authors could not conclude the relationship between lead characteristics and the development of TR due to the small number of patients.17 Lead characteristics data otherwise are lacking in other human studies. However, Wilkoff and colleagues, in their animal‐based study, found that expanded polytetrafluoroethylene‐coated coils are easily extracted compared to backfilled with medical adhesive coils and uncoated coils, as they are usually associated with less fibrosis and possibly less TR.37

As far as techniques, some experts suggest that the prolapsing technique is sometimes the preferred technique, as the leads are not directly placed, and therefore the risk of damaging the tricuspid apparatus is reduced. Rajappan explained the 3 techniques of RV lead placement, of which the prolapsing technique may be less traumatic compared to the direct‐crossing and drop‐down techniques.38 One of the disadvantages of the prolapsing technique is possible injury to the structures surrounding the tricuspid valve prior to getting into the RV. However, there is a lack of evidence on which of these techniques is associated with a higher risk of TR after lead implantation.

Based on experts' opinion, apically placed leads have the potential of tethering to the posterior leaflet of the tricuspid valve more than septally placed leads, which may suggest that sometimes ICD leads have higher TR associated with the leads because they have to be placed apically.

Although there are no data regarding surveillance, patients who may benefit from close echocardiography monitoring are those who develop new‐onset right‐sided heart failure symptoms, have preexisting TR, or those who have more than 1 apical lead.

Summary

Device‐related TR is usually due to either mechanical (perforation/laceration of leaflets, entrapment of leads resulting in scar tissue, or interference with valve coaptation) or physiological (asynchronized activation of the RV from apex to base) mechanisms. When clinically significant, management typically involves percutaneous extraction of the offending leads. Larger, prospective, and well‐controlled studies are needed to truly assess the incidence and timing of TR after lead implantation along with associated prognosis and mortality.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marion Tomasko for her contribution of the medical illustration.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Agarwal S, Tuzcu E, Rodriguez E, et al. Interventional cardiology perspective of functional tricuspid regurgitation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:565–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gibson TC, Davidson RC, DeSilvey DL. Presumptive tricuspid valve malfunction induced by a pacemaker lead: a case report and review of the literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1980;3:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seo Y, Ishizu T, Nakajima H, et al. Clinical utility of 3‐dimensional echocardiography in the evaluation of tricuspid regurgitation caused by pacemaker leads. Circ J. 2008;72:1465–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paniagua D, Aldrich HR, Lieberman EH, et al. Increased prevalence of significant tricuspid regurgitation in patients with transvenous pacemakers leads. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:1130–1132, A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Cock CC, Vinkers M, Van Campe LC, et al. Long‐term outcome of patients with multiple (≥3) noninfected transvenous leads: a clinical and echocardiographic study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23:423–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klutstein M, Balkin J, Butnaru A, et al. Tricuspid incompetence following permanent pacemaker implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009;32(suppl 1):S135–S137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Webster G, Margossian R, Alexander ME, et al. Impact of transvenous ventricular pacing leads on tricuspid regurgitation in pediatric and congenital heart disease patients. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2008;21:65–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kucukarslan N, Kirilmaz A, Ulusoy E, et al. Tricuspid insufficiency does not increase early after permanent implantation of pacemaker leads. J Card Surg. 2006;21:391–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leibowitz DW, Rosenheck S, Pollak A, et al. Transvenous pacemaker leads do not worsen tricuspid regurgitation: a prospective echocardiographic study. Cardiology. 2000;93:74–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim JB, Spevack DM, Tunick PA, et al. The effect of transvenous pacemaker and implantable cardioverter defibrillator lead placement on tricuspid valve function: an observational study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:284–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCarthy PM, Bhudia SK, Rajeswaran J, et al. Tricuspid valve repair: durability and risk factors for failure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:674–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morgan DE, Norman R, West RO, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of tricuspid regurgitation during ventricular demand pacing. Am J Cardiol. 1986;58:1025–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Skjaerpe T, Hattle L. Diagnosis of tricuspid regurgitation. Sensitivity of Doppler ultrasound compared with contrast echocardiography. Eur Heart J. 1985;6:429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Celiker C, Kucukoglu MS, Arat‐Ozkan A, et al. Right ventricular and tricuspid valve function in patients with two ventricular pacemaker leads. Jpn Heart J. 2004;45:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Postaci N, Eksi K, Bayata S, et al. Effect of the number of ventricular leads on right ventricular hemodynamics in patients with permanent pacemaker. Angiology. 1995;46:421–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rahko PS. Prevalence of regurgitant murmurs in patients with valvular regurgitation detected by Doppler echocardiography. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lin G, Nishimura RA, Connolly HM, et al. Severe symptomatic tricuspid valve regurgitation due to permanent pacemaker or implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator leads. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1672–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nucifora G, Badano LP, Allocca G, et al. Severe tricuspid regurgitation due to entrapment of the anterior leaflet of the valve by a permanent pacemaker lead: role of real time three‐dimensional echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2007;24:649–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maisel AS, Atwood JE, Goldberger AL. Hepatojugular reflux: useful in the bedside diagnosis of tricuspid regurgitation. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:781–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pitts WR, Lange RA, Cigarroa JE, et al. Predictive value of prominent right atrial V waves in assessing the presence and severity of tricuspid regurgitation. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:617–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rogers J, Bolling S. Current perspective and evolving management of tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation. 2009;119:2718–2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tribouilloy CM, Enriquez‐Sarano M, Bailey KR, et al. Quantification of tricuspid regurgitation by measuring the width of the vena contracta with Doppler color flow imaging: a clinical study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:472–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen TE, Wang CC, Chern MS, et al. Entrapment of permanent pacemaker lead as the cause of tricuspid regurgitation. Circ J. 2007;71:1169–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Groves AM, Win T, Charman SC, et al. Semi‐quantitative assessment of tricuspid regurgitation on contrast‐enhanced multidetector CT. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:715–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nagel E, Jungehulsing M, Smolarz K, et al. Diagnosis and classification of tricuspid valve insufficiency with dynamic magnetic resonance tomography: comparison with right ventricular angiography [in German]. Z Kardiol. 1991;80:561–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iskandar SB, Ann Jackson S, Fahrig S, et al. Tricuspid valve malfunction and ventricular pacemaker lead: case report and review of the literature. Echocardiography. 2006;23:692–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Champagne J, Poirier P, Dumesnil JG, et al. Permanent pacemaker lead entrapment: role of the transesophageal echocardiography. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25:1131–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang TY, Baba N. Cardiac pathology of transvenous pacemakers Am Heart J 1972;83:469–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krupa W, Kozlowski D, Derejko P, et al. Permanent cardiac pacing and its influence on tricuspid valve function. Folia Morphologica (Warszawa). 2001;60:249–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Novak M, Dvorak P, Kamaryt P, et al. Autopsy and clinical context in deceased patients with implanted pacemakers and defibrillators: intracardiac findings near their leads and electrodes. Europace. 2009;11:1510–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Loupy A, Messika‐Zeitoun D, Cachier A, et al. An unusual cause of pacemaker‐induced severe tricuspid regurgitation. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2008;9:201–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rickard J, Wilkoff BL. Extraction of implantable cardiac electronic devices. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2011;13:407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Glover BM, Watkins S, Mariani JA, et al. Prevalence of tricuspid regurgitation and pericardial effusions following pacemaker and defibrillator lead extraction. Int J Cardiol. 2010;145:593–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Franceschi F, Thuny F, Giorgi R, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of traumatic tricuspid regurgitation after percutaneous ventricular lead removal. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2168–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Groves P. Surgery of valve disease: late results and late complications. Heart. 2001;86:715–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Baman TS, Gupta SK, Valle JA, et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients with cardiac device‐related infection. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wilkoff BL, Belott PH, Love CJ, et al. Improved extraction of ePTFE and medical adhesive modified defibrillation leads from the coronary sinus and great cardiac vein. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rajappan K. Permanent pacemaker implantation technique: part II. Heart. 2009;95:334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]