Abstract

Background

Coronary artery disease (CAD) often occurs concurrently in patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS). However, the influence of concomitant CAD on the presence of atherosclerotic complex plaques in the aortic arch, which is associated with increased stroke risk, has not been fully assessed in patients with severe AS.

Hypothesis

We hypothesized that concomitant CAD would be associated with the presence of complex arch plaques in patients with severe AS.

Methods

The study population consisted of 154 patients with severe AS who had undergone transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and coronary angiography (71 male; mean age, 72 ± 8 years; mean aortic valve area, 0.67 ± 0.15 cm2). Aortic arch plaques were assessed using TEE, and complex arch plaques were defined as large plaques (≥4 mm), ulcerated plaques, or mobile plaques.

Results

The prevalence of aortic arch plaques (87% vs 70%; P = 0.03) and complex arch plaques (48% vs 20%; P < 0.001) was significantly greater in AS patients with CAD than in those without CAD. After adjustment for traditional atherosclerotic risk factors, we found that concomitant CAD was independently associated with the presence of complex arch plaques (odds ratio: 2.86, 95% confidence interval: 1.23‐6.68, P = 0.01).

Conclusions

In patients with severe AS, concomitant CAD is associated with severe atherosclerotic burden in the aortic arch. This observation suggests that AS patients with concomitant CAD are at a higher risk for stroke, and that careful evaluation of complex arch plaques by TEE is needed for the risk stratification of stroke in these patients.

Introduction

Atherosclerotic aortic arch plaques detected by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) are being increasingly recognized as stroke risk factors.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 In particular, the presence of complex arch plaques, such as large plaques and plaques with ulceration or mobile components, increase the stroke risk.6, 7, 8 In addition, the association between complex arch plaques and perioperative stroke risk has been reported in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.9, 10 Further, a close relationship between aortic stenosis (AS) and systemic atherosclerosis has been shown in previous studies. Coronary artery disease (CAD) is often found concurrently in patients with severe AS,11, 12, 13 and it requires aortic valve replacement (AVR) with concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).14, 15 Among patients who undergo AVR for severe AS, the perioperative stroke rate has been reported to be significantly higher in patients undergoing combined AVR and CABG than in those undergoing AVR alone.16, 17, 18, 19 The high perioperative stroke risk in AS patients with CAD may be influenced by a possible relationship between concomitant CAD and the presence of complex arch plaques, which is closely associated with stroke. In the present study, therefore, we evaluated the effect of concomitant CAD on the presence of aortic arch plaques detected by TEE in patients with severe AS.

Methods

Study Patients

The study included 177 consecutive patients with severe AS who had undergone TEE and coronary angiography. We excluded 14 patients with rheumatic valvular disease, 2 patients who had recurrent AS due to degenerative bioprosthetic valve, 2 patients who had undergone CABG, and 1 patient with thoracic aortic aneurysm with mural thrombus. We also excluded 4 patients in whom the aortic arch could not be visualized fully by TEE. Ultimately, 154 patients were enrolled in the study (71 male; mean age, 72 ± 8 years; mean aortic valve area, 0.67 ± 0.15 cm2). The severity of AS and cardiac function were assessed using transthoracic echocardiography.14 Left ventricular ejection fraction was measured by the biplane Simpson disc method. Aortic valve area (AVA) was obtained with the use of the standard continuity equation. Severe AS was defined as a maximal jet velocity of 4 m/s or greater or AVA <1.0 cm2.14, 15 Quantitative coronary angiography was performed using the view that showed the greatest degree of stenosis. CAD was defined as ≥70% diameter stenosis or a history of coronary revascularization. Left main stenosis ≥50% was scored as 2‐vessel disease. The hospital ethics committee approved the study protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Cardiovascular Risk Factor Assessment

Clinical data and history of risk factors such as age, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking were collected for each study patient. Diabetes mellitus was determined on the basis of the presence of an existing diagnosis; fasting blood glucose level, >126 mg/dL; glycohemoglobin A1c level, >6.5%; or the use of antidiabetic medications or insulin. Hypertensive status was defined by a systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mm Hg, or by the use of antihypertensive medications. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as serum cholesterol value of >220 mg/dL or the use of cholesterol‐lowering medications. Patients were classified as nonsmokers if they had never smoked or if they had stopped smoking for ≥1 year before the study. All other patients were classified as smokers.

Assessment of Aortic Arch Plaques by TEE

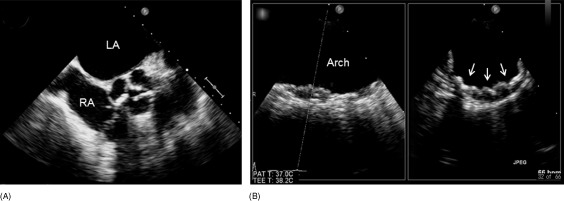

TEE was performed using a multiplane transducer, as described in previous publications.20, 21 The aortic arch was defined as the portion of the aorta between the curve at the end of the ascending aorta and the origin of the left subclavian artery. Plaques were defined as discrete protrusions of the intimal surface of the vessel that were ≥2 mm in thickness and differed in appearance and echogenicity from the adjacent intact intimal surface. The presence and location of plaques were recorded. In cases of multiple plaques, the most advanced lesion was considered. An ulceration was defined as a discrete indentation of the luminal surface of the plaque with base width and maximum depth of at least 2 mm each.6, 7 Plaques ≥4 mm in thickness, plaques with ulceration, or mobile components were defined as complex plaques (Figure 1).8 Echocardiographic data were interpreted by an experienced echocardiographer who was blinded to patient information.

Figure 1.

Transesophageal echocardiographic example of complex plaques in the aortic arch in a patient with aortic stenosis and coronary artery disease. (A) Severely stenotic aortic valves. (B) Complex arch plaques (arrows). Abbreviations: LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium.

Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. When 2 groups were compared, unpaired t test or Mann–Whitney U test was used, as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using a χ2 test or Fisher exact test. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association of atherosclerotic risk factors and the presence of CAD with the presence of any type of arch plaques or complex arch plaques. The association between concomitant CAD and the presence of any type of arch plaques or complex arch plaques was then evaluated using multivariate logistic regression analysis after adjustment for traditional atherosclerotic risk factors (age, gender [male], hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and hypercholesterolemia). Age and body mass index (BMI) were entered as continuous variables in regression analyses. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Clinical Characteristics

Among the 154 AS patients enrolled in this study, 46 patients (30%) had concomitant CAD (19 patients with single‐vessel disease and 27 with multivessel disease). The patient characteristics of the 154 patients according to the presence of concomitant CAD are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups with respect to the prevalence of male gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, atrial fibrillation, BMI, and the use of anticoagulants, angiotensin‐converting enzyme, or angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers and statins. However, age (P < 0.001), history of stroke (P = 0.03), and the use of antiplatelets (P < 0.001), calcium antagonists (P = 0.01), and β‐blockers (P = 0.048) were significantly higher, aortic jet velocity (P = 0.01) was lower in patients with concomitant CAD than in those without CAD.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics According to Presence of Concomitant CAD in Patients with Aortic Stenosis (n = 154)

| All | No CAD (n = 108) | CAD (n = 46) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 72 ± 8 | 70 ± 7 | 75 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| Male | 71 (46%) | 46 (43%) | 25 (54%) | 0.26 |

| Hypertension | 108 (70%) | 72 (67%) | 36 (78%) | 0.15 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 46 (30%) | 28 (26%) | 18 (39%) | 0.14 |

| Smokers | 44 (29%) | 28 (26%) | 16 (35%) | 0.30 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 62 (40%) | 40 (37%) | 22 (48%) | 0.26 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22 ± 4 | 22 ± 4 | 23 ± 4 | 0.40 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 21 (14%) | 14 (13%) | 7 (16%) | 0.67 |

| History of stroke | 17 (11%) | 8 (7%) | 9 (20%) | 0.03 |

| Medications | ||||

| Antiplatelets | 42 (27%) | 18 (17%) | 24 (52%) | <0.001 |

| Anticoagulants | 23 (15%) | 15 (14%) | 8 (17%) | 0.58 |

| ACE inhibitors/ARB | 67 (44%) | 49 (45%) | 18 (39%) | 0.48 |

| Calcium antagonists | 70 (45%) | 42 (39%) | 28 (61%) | 0.01 |

| β‐Blockers | 18 (12%) | 9 (8%) | 9 (20%) | 0.048 |

| Statins | 42 (27%) | 26 (24%) | 16 (35%) | 0.17 |

| Echocardiographic indices | ||||

| LVDD (mm) | 47 ± 7 | 47 ± 7 | 47 ± 6 | 0.89 |

| LVDS (mm) | 29 ± 9 | 29 ± 9 | 28 ± 8 | 0.58 |

| LVEF (%) | 58 ± 11 | 58 ± 10 | 57 ± 11 | 0.67 |

| Aortic jet velocity (m/s) | 4.8 ± 0.9 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 0.01 |

| Aortic valve area (cm2) | 0.67 ± 0.15 | 0.67 ± 0.16 | 0.68 ± 0.15 | 0.64 |

| Annuloaortic diameter (mm) | 22 ± 2 | 22 ± 2 | 22 ± 2 | 0.56 |

| Ascending aortic diameter (mm) | 36 ± 5 | 36 ± 6 | 34 ± 5 | 0.09 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers; CAD, coronary artery disease; LVDD, left ventricular end‐diastolic dimension; LVDS, left ventricular end‐systolic dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Categorical variables are expressed as number of patients (percentage) and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation.

Aortic Arch Plaques Assessed by TEE

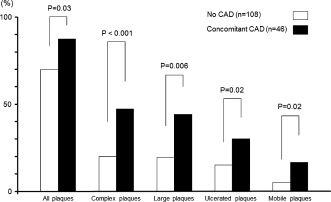

Left atrial appendage thrombus was detected in 5 patients by TEE, and 4 of these patients had atrial fibrillation. Aortic arch plaques were identified in 116 patients (75%) and complex arch plaques in 44 patients (29%) (large plaques in 39 [25%], ulcerated plaques in 29 [18%], and mobile plaques in 14 [9%] patients). The prevalence of aortic arch plaques according to the presence of concomitant CAD is shown in Table 2. Prevalence of any type of arch plaques (87% vs 70%, P = 0.03) and complex arch plaques (48% vs 20%, P < 0.001) was significantly greater in AS patients with concomitant CAD than in those without CAD (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Aortic Arch Plaques According to the Presence of Concomitant CAD in Patients with Aortic Stenosis

| All | No CAD (n = 108) | CAD (n = 46) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any type of plaques | 116 (75%) | 76 (70%) | 40 (87%) | 0.03 |

| Complex plaques | 44 (29%) | 22 (20%) | 22 (48%) | <0.001 |

| Large plaques | 39 (25%) | 19 (18%) | 20 (44%) | 0.006 |

| Ulcerated plaques | 29 (18%) | 15 (14%) | 14 (30%) | 0.02 |

| Mobile plaques | 14 (9%) | 6 (6%) | 8 (17%) | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease.

Categorical variables are expressed as number of patients (percentage).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the prevalence of arch plaques between aortic stenosis patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and those without CAD.

We evaluated the association between the presence of aortic arch plaques with traditional atherosclerotic risk factors and concomitant CAD (Table 3). Univariate logistic analyses showed that age (odds ratio [OR]: 1.12 per year increase, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.06‐1.18, P < 0.001) and concomitant CAD (OR: 2.81, 95% CI: 1.08‐7.28, P = 0.03) were associated with the presence of any type of arch plaques; further, age (OR: 1.06 per year increase, 95% CI: 1.01‐1.11, P = 0.03), hypertension (OR: 2.90, 95% CI: 1.18‐7.12, P = 0.02) and concomitant CAD (OR: 3.58, 95% CI: 1.70‐7.54, P < 0.001) were associated with the presence of complex arch plaques. In the present cohort, statin treatment and BMI were not associated with the presence of any type of arch plaques (OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 0.55‐3.00, P = 0.57 and OR: 1.02 per unit increase, 95% CI: 0.92‐1.12, P = 0.77, respectively) and that of complex arch plaques (OR: 1.85, 95% CI: 0.87‐3.93, P = 0.11 and OR: 0.97 per unit increase, 95% CI: 0.88‐1.06, P = 0.49, respectively). In multivariate logistic analyses, after adjusting for traditional atherosclerotic risk factors (R 2 = 0.12), concomitant CAD was found to be independently associated with the presence of complex arch plaques (OR: 2.86, 95% CI: 1.23‐6.68, P = 0.01) but not with the presence of any type of arch plaques (OR: 1.60, 95% CI: 0.56‐4.58, P = 0.38).

Table 3.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analyses for Presence of Aortic Arch Plaques in Patients With Aortic Stenosis

| Any Type of Plaques | Complex Plaques | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (per y) | 1.12 (1.06‐1.18) | <0.001 | 1.11 (1.04‐1.18) | 0.002 | 1.06 (1.01‐1.11) | 0.03 | 1.03 (0.97‐1.09) | 0.36 |

| Male | 0.76 (0.36‐1.58) | 0.46 | 0.91 (0.35‐2.33) | 0.84 | 0.90 (0.44‐1.81) | 0.76 | 0.88 (0.36‐2.20) | 0.79 |

| Hypertension | 1.53 (0.71‐3.32) | 0.28 | 1.13 (0.47‐2.68) | 0.79 | 2.90 (1.18‐7.12) | 0.02 | 2.39 (0.90‐6.34) | 0.08 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.27 (0.56‐2.88) | 0.58 | 1.27 (0.50‐3.22) | 0.62 | 1.25 (0.59‐2.63) | 0.57 | 0.83 (0.35‐1.95) | 0.66 |

| Smokers | 1.04 (0.45‐2.40) | 0.93 | 1.39 (0.51‐3.83) | 0.52 | 1.71 (0.79‐3.70) | 0.17 | 1.83 (0.71‐4.70) | 0.21 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.94 (0.45‐1.97) | 0.86 | 0.90 (0.38‐2.14) | 0.80 | 1.48 (0.73‐2.99) | 0.28 | 1.23 (0.55‐2.74) | 0.61 |

| Concomitant CAD | 2.81 (1.08‐7.28) | 0.03 | 1.60 (0.56‐4.58) | 0.38 | 3.58 (1.70‐7.54) | <0.001 | 2.86 (1.23‐6.68) | 0.01 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

Several studies using TEE have shown that patients with severe AS have a greater prevalence of aortic arch plaques,21, 22, 23, 24 and that the presence of complex arch plaques is closely related to stroke risk in these patients.21 In the present study, we showed that the prevalence of complex arch plaques further increases in AS patients with CAD, and that concomitant CAD is independently associated with the presence of complex arch plaques in these patients. Our findings suggest that careful evaluation of complex arch plaques by TEE is needed in AS patients with concomitant CAD for the risk stratification of stroke.

Progression of atherosclerosis is considered to be a single entity that affects different vascular territories such as coronary arteries, carotid arteries, and aorta.25 Previous studies have reported the association between concomitant CAD and aortic plaques in the thoracic aorta assessed by TEE in AS patients.23, 26 Tribouilloy et al26 initially reported that the presence of aortic plaques detected by TEE was a significant predictor of CAD in patients with severe AS. Similarly, Goland et al23 showed that concomitant CAD was associated with the presence of aortic plaques observed by intraoperative TEE in AS patients who had undergone AVR. In addition to these studies, an important strength of our study was the relation of concomitant CAD to complex arch plaques that are closely correlated with stroke risk.6, 7, 8 In the present study, we have shown that only complex arch plaques are independently associated with concomitant CAD in AS patients after adjustment for atherosclerotic risk factors. In patients with severe AS, only the presence of severe arch plaques may have a significant association with concomitant CAD because most patients with severe AS already have any type of arch plaques.21, 22, 24

For severe AS patients with significant CAD, concomitant CABG at the time of AVR is a standard treatment strategy.14, 15 Previous studies consistently reported that the incidence of stroke after combined valve surgery and CABG is significantly greater than that after valve surgery alone.16 Furthermore, the perioperative risk of combined AVR and CABG is higher than the risk of AVR alone.17, 18 Moreover, a recent study using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that patients with combined valve and CABG surgery, mainly combined AVR and CABG, were more likely to have postoperative ischemic change than those with valve surgery alone.19 Therefore, not only symptomatic but also asymptomatic perioperative stroke, which is associated with cognitive impairment after cardiac surgery,19 can often occur in AS patients with CAD. Our results indicate that high operative stroke risk in these patients may be attributed, in part, to high prevalence of severe arch plaques, which is strongly associated with cerebrovascular events.

With recent developments in transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), this technique is being increasingly recognized as a feasible alternative method to conventional surgical AVR.15, 27, 28, 29 However, perioperative stroke in TAVI remains a significant problem. Cerebral infarction after TAVI diagnosed using MRI is very common, with a prevalence of approximately 80%.30, 31 This might result not only in embolization of crushed stenotic native valve due to implantation of the devices, but also in that of debris from aortic arch plaques.30 In a recent study, Fairbairn et al31 have reported that the severity of aortic arch plaques diagnosed by TEE is an independent predictor of new cerebral infarcts diagnosed by MRI after TAVI. Currently, for AS patients with concomitant CAD, several new indications, such as combined TAVI and percutaneous coronary intervention, have been proposed as an alternative treatment to combined AVR and CABG.32, 33 However, the perioperative risk of stroke, including asymptomatic stroke, should be considered for these indications in future studies.

Study Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. First, in the present cohort, prevalence of the use of statins was relatively low both in CAD and non‐CAD patients. One of the reasons is because our study population may have included many patients who were first diagnosed with hypercholesterolemia. This study was a retrospective analysis and may be subject to selection bias. Second, it should be noted that our study group was relatively small. Our data may therefore need to be confirmed in large patient populations. Third, we did not mention the prevalence of arch plaques in CAD patients with a normal aortic valve. Furthermore, postoperative data were not available for all patients in this study. Future studies should assess the differences in the prevalence of arch plaques between CAD patients with AS and those with a normal aortic valve, and also confirm an association between complex arch plaques and postoperative stroke events. Finally, the small portion of the aortic arch obscured by the tracheal air column may not be seen on TEE. Moreover, 3‐dimensional TEE may have better sensitivity and specificity for imaging of plaques. In the present study, however, we used only simultaneous multiplane imaging by real‐time 3‐dimensional TEE for the assessment of arch plaques (Figure 1), but did not use full‐volume or live 3‐dimensional imaging. Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first study to indicate a close association between concomitant CAD and complex arch plaques detected by TEE associated with a high risk of stroke in patients with severe AS.

Conclusion

In patients with severe AS, concomitant CAD is associated with the presence of complex plaques in the aortic arch, which is related to stroke risk. This observation suggests that AS patients with concomitant CAD are at a higher risk for stroke, which explains, at least in part, the higher perioperative stroke risk in these patients as compared to that in patients with AS alone, and that careful evaluation of complex arch plaques by TEE is needed for the risk stratification of stroke in AS patients with concomitant CAD.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Amarenco P, Cohen A, Tzourio C, et al. Atherosclerotic disease of the aortic arch and the risk of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1474–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones EF, Kalman JM, Calafiore P, et al. Proximal aortic atheroma: an independent risk factor for cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 1995;26:218–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Di Tullio MR, Sacco RL, Gersony D, et al. Aortic atheromas and acute ischemic stroke: a transesophageal echocardiographic study in an ethnically mixed population. Neurology. 1996;46:1560–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tunick PA, Rosenzweig BP, Katz ES, et al. High risk for vascular events in patients with protruding aortic atheromas: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1085–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Atherosclerotic disease of the aortic arch as a risk factor for recurrent ischemic stroke: the French Study of Aortic Plaques in Stroke Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1216–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Di Tullio MR, Russo C, Jin Z, et al. Aortic arch plaques and risk of recurrent stroke and death. Circulation. 2009;119:2376–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Di Tullio MR, Sacco RL, Savoia MT, et al. Aortic atheroma morphology and the risk of ischemic stroke in a multiethnic population. Am Heart J. 2000;139:329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kronzon I, Tunick PA. Aortic atherosclerotic disease and stroke. Circulation. 2006;114:63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Katz ES, Tunick PA, Rusinek H, et al. Protruding aortic atheromas predict stroke in elderly patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass: a review of our experience with intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stern A, Tunick PA, Culliford AT, et al. Protruding aortic arch atheromas: risk of stroke during heart surgery with and without aortic arch endarterectomy. Am Heart J. 1999;138:746–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stewart BF, Siscovick D, Lind BK, et al. Clinical factors associated with calcific aortic valve disease. Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:630–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vandeplas A, Willems JL, Piessens J, et al. Frequency of angina pectoris and coronary artery disease in severe isolated valvular aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 1988;62:117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Exadactylos N, Sugrue DD, Oakley CM. Prevalence of coronary artery disease in patients with isolated aortic valve stenosis. Br Heart J. 1984;51:121–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Kanu C, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2006;114:e84–e231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) ; European Association for Cardio‐Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2451–2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Newman MF, Mathew JP, Grocott HP, et al. Central nervous system injury associated with cardiac surgery. Lancet. 2006;368:694–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Craver JM, Gorldstein J, Jones EL, et al. Clinical, hemodynamic, and operative descriptors affecting outcome of aortic valve replacement in elderly versus young patients. Ann Surg. 1984;199:733–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Almassi GH, Sommers T, Moritz TE, et al. Stroke in cardiac surgical patients: determinants and outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barber MPA, Hach S, Tippett LJ, et al. Cerebral ischemic lesions on diffusion‐weighted imaging are associated neurocognitive decline after cardiac surgery. Stroke. 2008;39:1427–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sugioka K, Hozumi T, Sciacca RR, et al. Impact of aortic stiffness on ischemic stroke in elderly patients. Stroke. 2002;33:2077–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sugioka K, Matsumura Y, Hozumi T, et al. Relation of aortic arch complex plaques to risk of cerebral infarction in patients with aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:1002–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weisenberg D, Sahar Y, Sahar G, et al. Atherosclerosis of the aorta is common in patients with severe aortic stenosis: an intraoperative transesophageal echocardiographic study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goland S, Trento A, Czer LS, et al. Thoracic aortic arteriosclerosis in patients with degenerative aortic stenosis with and without existing coronary artery disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Osranek M, Pilip A, Patel PR, et al.: Amounts of aortic atherosclerosis in patients with aortic stenosis as determined by transesophageal echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:713–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Viles‐Gonzalez JF, Fuster V, Badimon JJ. Atherothrombosis: a widespread disease with unpredictable and life‐threatening consequences. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1197–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tribouilloy C, Peltier M, Rey JL, et al. Use of transesophageal echocardiography to predict significant coronary artery disease in aortic stenosis. Chest. 1998;113:671–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thomas M, Schymik G, Walther T, et al. Thirty‐day results of the SAPIEN aortic Bioprosthesis European Outcome (SOURCE) Registry: a European registry of transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the Edwards SAPIEN valve. Circulation. 2010;122:62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rodes‐Cabau J, Webb JG, Cheung A, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for the treatment of severe symptomatic aortic stenosis in patients at very high or prohibitive surgical risk: acute and late outcomes of the multicenter Canadian experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1080–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kahlert P, Knipp SC, Schlamann M, et al. Silent and apparent cerebral ischemia after percutaneous transfemoral aortic valve implantation: a diffusion‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging study. Circulation. 2010;121:870–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fairbairn TA, Mather AN, Bijsterveld P, et al. Diffusion‐weighted MRI determined cerebral embolic infarction following transcatheter aortic valve implantation: assessment of predictive risk factors and the relationship to subsequent health status. Heart. 2012;98:18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Masson JB, Lee M, Boone RH, et al. Impact of coronary artery disease on outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;76:165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gautier M, Pepin M, Himbert D, et al. Impact of coronary artery disease on indications for transcatheter aortic valve implantation and on procedural outcomes. EuroIntervention. 2011;7:549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]