ABSTRACT

Background

Current data on the management of patients in cardiac rehabilitation (CR) after an acute hospital stay due to ST‐segment elevation or non–ST segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (STE‐ACS or NSTE‐ACS) are limited. We aimed to describe patient characteristics, risk factor management, and lipid target achievement of patients in CR in Germany and compare the 2 groups.

Hypothesis

With respect to the risk factor pattern and treatment effects during a CR stay, there are important differences between STE‐ACS and NSTE‐ACS patients.

Methods

Comparison of 7950 patients by STE‐ACS or NSTE‐ACS status in the Transparency Registry to Objectify Guideline‐Oriented Risk Factor Management registry (2010) who underwent an inpatient CR period of about 3 weeks.

Results

STE‐ACS patients compared to NSTE‐ACS patients were significantly younger (60.5 vs 64.4 years, P < 0.0001), and had diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or any risk factor (exception: smoking) less often. At discharge, in STE‐ACS compared to NSTE‐ACS patients, the low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) <100 mg/dL goal was achieved by 75.3% and 76.2%, respectively (LDL‐C <70 mg/dL by 27.7% and 27.4%), the high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol goal of >50 mg/dL in women and >40 mg/dL in men was achieved by 49.3% and 49.0%, respectively, and the triglycerides goal of <150 mg/dl was achievedby 72.3% and 74.3%, respectively (all comparisons not significant). Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure were 121/74 and 123/74 mm Hg, respectively (P < 0.0001 systolic, diastolic not significant). The maximum exercise capacity was 110 and 102 W, respectively (P < 0.0001), and the maximum walking distance was 581 and 451 meters, respectively (P value not significant).

Conclusions

Patients with STE‐ACS and NSTE‐ACS differed moderately in their baseline characteristics. Both groups benefited from the participation in CR, as their lipid profile, blood pressure, and physical fitness improved.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases, in particular coronary artery disease (CAD), remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in most regions worldwide including Germany.1 Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) with ST‐elevation (STE‐ACS) or ACS without ST‐elevation (NSTE‐ACS) represents a life‐threatening condition that calls for acute treatment and subsequently for comprehensive secondary prevention of recurrent cardiac events. STE‐ACS is generally a sign of acute total coronary occlusion and more often results in in‐hospital death.2, 3 However, NSTE‐ACS is associated with a higher mortality at 4 years, which is widely unrecognized or underestimated.4, 5, 6, 7

Modern cardiac rehabilitation (CR) comprises early mobilization with exercise training, health education regarding lifestyles impacting on cardiac risk factors, and sometimes some relaxation training, stress management, or psychological counseling.8, 9 CR has an important role as part of integrated medical and nursing care to help patients who seek help in overcoming the trauma, bridge the gap between acute hospital treatment and long‐term care, and adjust their lifestyle to accommodate a chronic condition.9 For example, CR promotes long‐term positive health behaviors such as physical activity.10

According to a recent meta‐analysis of 34 randomized controlled trials with over 6000 patients, exercise‐based CR was related to a lower risk of reinfarction (odds ratio [OR]: 0.53, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.38‐0.76), cardiac mortality (OR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.46‐0.88), and all‐cause mortality (OR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.58‐0.95).11 Further, in stratified analyses, treatment effects were consistent regardless of study periods, duration of CR, or time beyond the active intervention. Exercise‐based CR had favorable effects on cardiovascular risk factors including smoking, blood pressure, body weight, and lipid profile.11

In Germany, CR programs for patients with ACS may start during the acute hospital stay but are usually initiated during a 3‐week stay in specific recovery/rehabilitation hospitals after transfer from the acute clinic.12 In this setting in 2002, the ACOS (Acute Coronary Syndromes) registry found an independent and strong association of CR, with markedly reduced total mortality and major adverse clinical outcomes during a 1‐year follow‐up after STE‐ACS or NSTE‐ACS.13

As CR for many ACS patients provides the important link between the acute care hospital and the long‐term primary care, practices and outcomes during the CR stay are highly relevant. To our knowledge, no current studies have looked into similarities or differences of patients with STE‐ACS or NSTE‐ACS in the CR setting. TROL (Transparency Registry to Objectify Guideline‐Oriented Risk Factor Management) is one of the largest registries on CR in Europe and has been used, among others, for the description of secular trends between 2000 and 2010 in the management of patients in real‐world CR.14, 15

We used current data from the TROL registry to describe in patients with STE‐ACS or NSTE‐ACS (1) characteristics including demographics, cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities; (2) risk‐factor management including drug treatment; and (3) target‐level attainment of lipid parameters and blood pressure.

Methods

Centers

Centers were eligible to participate in this prospective registry if they had a significant number of cardiovascular rehabilitation patients and were selected from all over Germany to ensure that all 16 federal states were represented adequately.14, 16 Participating physicians documented inpatients on standard paper case report forms. The ethics committee of the Bavarian Physician Chamber approved the study, and all patients provided written informed consent. We report an analysis of the dataset of the year 2010 with adequate and complete information on STE‐ACS and NSTE‐ACS as the qualifying event for the rehabilitation stay. The data of patients with unstable angina were included in the NSTE‐ACS group.

Variables

Parameters as displayed in the tables and figures were collected. Information on drug classes, but not on individual drugs, during the acute hospital stay prior to CR was collected.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as absolute numbers, percentages, or means with standard deviations. The frequencies of categorical variables in populations were compared by χ2 test for the patient demographics, risk factors, and comorbidities. Continuous variables were compared by 2‐tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test. Percentages were calculated on the basis of patients with data for each respective parameter (ie, no percentages for missing values provided). The analysis was performed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Demographics and Characteristics at CR Initiation

Total Cohort

Overall, 7950 patients were eligible for the present analysis, among them 4735 with STE‐ACS (59.6%) and 3215 with NSTE‐ACS (40.4%). The great majority of patients were fully or partly institutionalized for CR (2010: 95.3%), whereas ambulatory CR did not have a major role (4.7%). About half of the patients were retired (48.3%). Only 3.2% of patients were enrolled in the disease‐management program for CAD.

Demographic and clinical characteristics in total and by ACS subgroup are summarized in Table 1. The proportion of males in total was 75.6%, the average age was 62.1 ± 12.0 years, and the mean body mass index was 28.4 ± 4.9 kg/m2. Cardiovascular risk factors were prevalent, in particular lipid disorders (95.5%), arterial hypertension (84.3%), diabetes mellitus (30.3%), and former or current smoking (47.1% or 19.8%, respectively). In addition to CAD, 9.1% of patients suffered from peripheral artery disease, and 6.0% had a prior stroke event.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Factors in Patients With STE‐ACS and NSTE‐ACS

| Parameter | Total, N = 7950 | STE‐ACS, n = 4735 | NSTE‐ACS, n = 3215 | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y | 62.1 ± 12.0 | 60.5 ± 11.9 | 64.4 ± 11.9 | <0.0001 |

| Gender, male, % | 75.6 | 77.8 | 72.3 | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.4 ± 4.9 | 28.4 ± 4.8 | 28.5 ± 5.0 | 0.34 |

| Comorbidity, % | ||||

| Stroke | 6.0 | 5.4 | 7.0 | <0.01 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 9.1 | 7.5 | 11.4 | <0.0001 |

| Carcinoma | 6.3 | 5.6 | 7.3 | <0.01 |

| COPD | 11.6 | 10.1 | 13.8 | <0.0001 |

| At least 1 comorbidity | 36.3 | 32.4 | 42.1 | <0.0001 |

| No. of concomitant diseases | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | <0.0001 |

| Risk factors, % | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 30.3 | 27.6 | 34.3 | <0.0001 |

| Hyperlipoproteinemia | 95.5 | 95.7 | 95.3 | 0.30 |

| Arterial hypertension | 84.3 | 81.7 | 88.2 | <0.0001 |

| Current smoking | 19.8 | 21.5 | 17.5 | <0.0001 |

| Previous smoking | 47.1 | 48.5 | 45.1 | <0.01 |

| CAD in family history | 34.7 | 35.3 | 33.9 | 0.24 |

| At least 1 risk factor | 99.6 | 99.5 | 99.8 | 0.07 |

| Number of risk factors | 3.1 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 0.15 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; STE‐ACS, ST‐elevation acute coronary syndromes; NSTE‐ACS, non–ST‐elevation acute coronary syndromes.

P values refer to the comparison between STE‐ACS and NSTE‐ACS.

STE‐ACS vs NSTE‐ACS Characteristics

STE‐ACS patients compared to NSTE‐ACS patients were significantly younger (60.5 vs 64.4 years, P < 0.0001), and in line with the lower age, they had diabetes mellitus or hypertension less often, respectively, whereas the proportion of smoking patients was higher in the STE‐ACS group.

For most patients, myocardial infarction was the first event they had experienced (STE‐ACS, 88.8% vs NSTE‐ACS, 90.0%). With respect to the indication for CR, STE‐ACS patients reported chronic CAD (65.6% vs 61.9%, P < 0.001) and previous cardiac arrest significantly more often (6.9% vs 3.4%, P < 0.0001), and a history of previous bypass surgery less often (16.3% vs 26.2%, P < 0.001; Table 2). Patients with STE‐ACS received drug‐eluting stents (DES) less often, which is in line with the higher proportion of diabetics in the NSTE‐ACS group (DES alone in 41.4% vs 46.7%, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Cardiac Diagnoses and Indication for Cardiac Rehabilitation

| Total, N = 7950 | STE‐ACS, n = 4735 | NSTE‐ACS, n = 3215 | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indication for CR, % | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | — |

| First event | 89.3 | 88.8 | 90.0 | 0.09 |

| Recurrent | 10.7 | 11.2 | 10.0 | 0.09 |

| STE‐ACS | 59.6 | 100.0 | 0.0 | <0.0001 |

| Anterior wall | 48.4 | 48.4 | — | — |

| Posterior/lateral wall | 51.6 | 51.6 | — | — |

| NSTE‐ACS | 42.2 | 3.0 | 100.0 | <0.0001 |

| Unstable angina | 12.2 | 11.6 | 13.1 | <0.05 |

| CAGB | 20.3 | 16.3 | 26.2 | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 5.5 | 6.9 | 3.4 | <0.0001 |

| Chronic CAD | 64.1 | 65.6 | 61.9 | <0.001 |

| Diagnostics/therapy, % | ||||

| Coronary angiography | 98.0 | 98.3 | 87.5 | <0.05 |

| Thrombolytic therapy | 4.0 | 4.9 | 2.6 | <0.0001 |

| PCI | 79.9 | 86.2 | 70.6 | <0.0001 |

| PCI <12 hours postevent | 79.9 | 85.3 | 70.1 | <0.0001 |

| Stent | 78.6 | 84.7 | 69.7 | <0.0001 |

| Bare‐metal stent | 60.2 | 62.0 | 56.9 | <0.001 |

| Drug‐eluting stent | 43.3 | 41.4 | 46.7 | <0.001 |

| Both | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 0.61 |

| Vessel | ||||

| RIVA/LAD | 49.6 | 50.7 | 47.7 | <0.05 |

| RCA | 39.7 | 43.4 | 33.4 | <0.0001 |

| RCX | 25.0 | 20.9 | 32.1 | <0.0001 |

| LMCA | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2.9 | <0.01 |

| Bypass | 4.3 | 2.7 | 6.9 | <0.0001 |

| ICD implantation | 2.8 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 0.05 |

| CRT‐P | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.16 |

| CRT‐D | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.21 |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CR, cardiac rehabilitation; CRT‐D, cardiac resynchronization therapy–defibrillator, CRT‐P, cardiac resynchronization therapy–pacemaker; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LAD, left anterior descending artery, LMCA, left main coronary artery, NSTE‐ACS, non–ST‐elevation acute coronary syndromes; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention, RCA, right coronary artery; RCX, right circumflex artery, STE‐ACS, ST‐elevation acute coronary syndromes.

P values refer to the comparison between STE‐ACS and NSTE‐ACS.

During the acute hospital stay prior to CR, STE‐ACS patients had received percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (85.3% vs 70.1%, P < 0.0001), stent implantation (84.7% vs 69.7%, P < 0.0001), and thrombolytic therapy (4.9% vs 2.6%, P < 0.0001) more often. On echocardiography, left ventricular ejection fraction was normal less often in STE‐ACS patients (53.1% vs 69.1%, P < 0.0001). On electrocardiograph, atrial fibrillation was recorded less frequently in STE‐ACS patients (3.5% vs 6.0%, P < 0.0001). With respect to physical activity of at least 90 minutes per week prior to CR, no differences were reported between the STE‐ACS and NSTE‐ACS patients (54.2% vs 52.1%, P = 0.09).

Interventions During CR

Patients in both groups underwent daily physical training (98.7% overall) and dietary sessions (90.0%). Of note, psychological counseling was provided more often to patients in the STE‐ACS group (62.3% vs 54.9%, P < 0.0001) as was smoking cessation training (24.5% vs 17.7%, P < 0.0001).

Cardiovascular and Lipid‐Lowering Drug Utilization During the CR Stay

Total Cohort

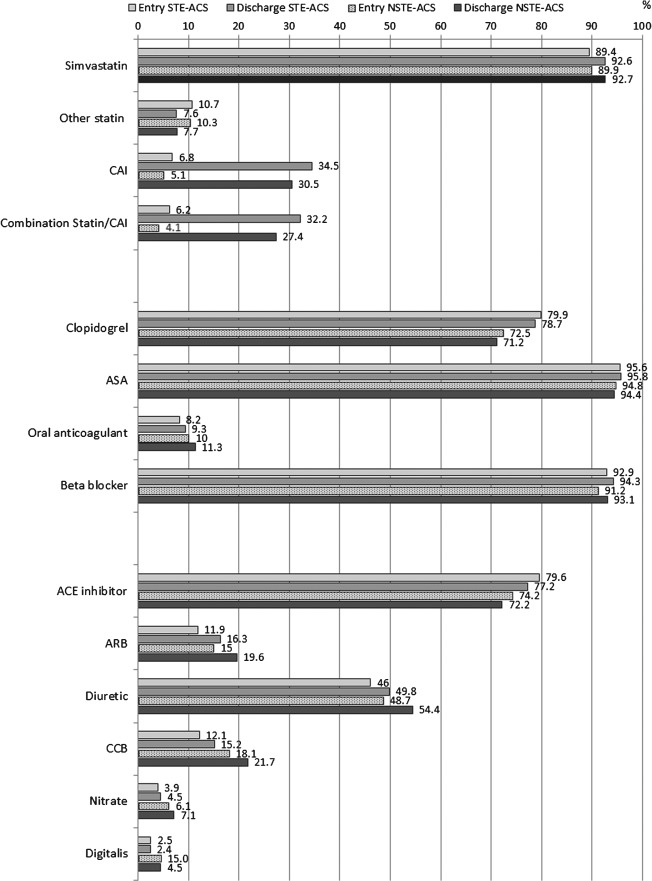

Drug treatment at entry and discharge is shown in Figure 1. In the total cohort, the majority of patients received statins at entry (overall in 90.6%, more often in STE‐ACS compared to NSTE‐ACS: 92.2% vs 88.2%, P < 0.0001). In particular, simvastatin was used (89.6%) at a mean dose of 33.5 ± 13.7 mg/d. At the end of the CR stay, almost all patients received statin therapy (overall in 94.2%, more often in STE‐ACS compared to NSTE‐ACS, 95.3% vs 93.0%, P < 0.0001). The mean dose of simvastatin increased to 35.3 ± 14.3 mg/d.

Figure 1.

Between the patients in the ST‐segment elevation or non–ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (STE‐ACS or NSTE‐ACS) groups, all differences between the shown medications were statistically significant, with the exception of simvastatin at entry and discharge, and ASA at discharge. Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASA, acetylic salicylic acid; CAI, cholesterol absorption inhibitor; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

Treatment with a cholesterol absorption inhibitor increased during CR (from 5.4% to 30.3%), and the drug was more frequently used in STE‐ACS. Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA; aspirin) use remained unchanged at a high level (at entry and discharge 95.2%), whereas clopidogrel alone or in combination with ASA decreased slightly (76.5% at entry, 75.7% at discharge, more often in STE‐ACS patients). Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) were frequently used in this study (at discharge 75.1% and 17.1%, respectively). Oral anticoagulation, ARBs, diuretics, calcium channel blockers, nitrates, and digitalis were more often administered to NSTE‐ACS patients.

Lipid Target Level Attainment

Total Cohort

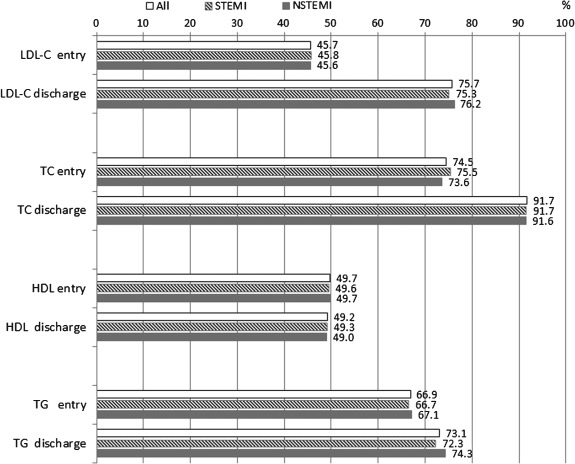

Lipid levels are shown in Table 3, and target level attainment at entry and at discharge are shown in Figure 2. In the total cohort at entry, mean total cholesterol was 177 mg/dL, mean low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) was 106 mg/dl, mean high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C) was 44 mg/dL, and mean triglycerides (TG) was 139 mg/dL. At discharge, values had considerably improved (total cholesterol 152 mg/dL, mean LDL‐C 86 mg/dL, and mean TG 127 mg/dL), whereas HDL‐C remained unchanged. No relevant differences between STE‐ACS and NSTE‐ACS were noted for lipid values at entry and discharge.

Table 3.

Absolute Lipid Values, Blood Pressure, and Exercise Capacity at Entry and Discharge

| Total, N = 7950 | STE‐ACS, n = 4735 | NSTE‐ACS, n = 3215 | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | ||||

| Entry | 177 ± 42 | 176 ± 41 | 178 ± 43 | 0.12 |

| Discharge | 153 ± 33 | 152 ± 33 | 153 ± 34 | 0.36 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | ||||

| Entry | 106 ± 34 | 106 ± 33 | 107 ± 35 | 0.57 |

| Discharge | 86 ± 26 | 86 ± 26 | 86 ± 26 | 0.57 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | ||||

| Entry | 44 ± 12 | 44 ± 12 | 44 ± 12 | <0.05 |

| Discharge | 44 ± 11 | 43 ± 11 | 44 ± 11 | <0.05 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | ||||

| Entry | 139 ± 93 | 139 ± 93 | 139 ± 92 | 0.40 |

| Discharge | 127 ± 77 | 127 ± 74 | 126 ± 80 | 0.11 |

| Systolic/diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||

| Entry | 129 ± 20/77 ± 12 | 127 ± 20/78 ± 12 | 131 ± 20/77 ± 12 | <0.0001/0.08 |

| Discharge | 122 ± 16/74 ± 10 | 121 ± 15/74 ± 10 | 123± 16/74 ± 10 | <0.0001/0.48 |

| Maximum exercise capacity, W | ||||

| Entry | 93 ± 40 | 95 ±39 | 89 ±41 | <0.0001 |

| Discharge | 107 ± 41 | 110 ± 40 | 102 ± 41 | <0.0001 |

| Walkings distance, m | ||||

| Entry | 339 ± 405 | 356 ± 438 | 319 ± 361 | 0.47 |

| Discharge | 520 ± 938 | 581 ± 1018 | 451 ± 836 | 0.07 |

Abbreviations: HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein. NSTE‐ACS, non–ST‐elevation acute coronary syndromes; STE‐ACS, ST‐elevation acute coronary syndromes.

P values refer to the comparison between STE‐ACS and NSTE‐ACS.

Figure 2.

Treatment goals: LDL‐C <100 mg/dL; total cholesterol <200 mg/dL; HDL‐C goal >50 mg/dL in women; >40 mg/dL in men; triglycerides <150 mg/dL. Between patients in the ST‐segment elevation or non–ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome groups, there were no statistically significant differences between the goal attainment rates for any of the shown lipid parameters. Abbreviations: HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; NSTEMI, non–ST‐elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST‐elevation myocardial infarction; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Control rates of the various lipid parameters between entry and discharge improved substantially, with the exception of HDL‐C. No relevant differences between STE‐ACS and NSTE‐ACS were noted for the target level achievement at entry and discharge.

Blood Pressure and Exercise Capacity

Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure for the overall cohort decreased from 129/77 mm Hg to 122/74 mm Hg. Both at entry and discharge, STE‐ACS patients had significantly lower systolic and diastolic values compared to NSTE‐ACS patients. The maximum exercise capacity increased from 93 to 107 W (better values in STE‐ACS), and the maximum walking distance from 339 to 520 m (no difference, Table 3).

Discussion

The present analysis provides an in‐depth characterization of patients with ACS who underwent a CR stay after the acute hospital period. Patients with NSTE‐ACS compared to STE‐ACS are at the time of infarction at lower risk, but have a similar or even worse prognosis in the long term.5 Thus, both groups require stringent risk‐factor management with antiplatelets, statin‐based reduction of elevated LDL‐C, and cardioprotection with inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system and β‐blockers. We show that the rates of prescriptions of therapies as recommended in the guidelines are encouragingly high, and that a 3‐week CR period, probably due to optimized medication usage, improves lipid profile, blood pressure, and exercise capacity favorably.

As the average duration of hospital stays for patients with ACS continuously decreases, there is very limited time to set up a patient‐tailored pharmacology schedule. Further, there is a lack of time for initiation of comprehensive educational measures to help the patients adopt to their new situation and to acquire a healthier lifestyle. The efficacy of in‐hospital prevention interventions administered soon after acute cardiac events is unclear.17 Therefore, the initiation of CR after acute myocardial infarction is a class I recommendation and has an important role in secondary prevention.18, 19

In recent years, substantial evidence has been gathered on the characteristics of patients with ACS in the acute care and ambulatory setting. For example, on an international basis, data were collected in GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events),20, 21 in the EPICOR (long‐tErm follow‐up of antithrombotic management Patterns In acute CORonary syndrome patients) registry,22 or the GWTG registry (Get With The Guidelines)23 in the United States with multiple analyses. In Germany, detailed data on STE‐ACS and NSTE‐ACS have been gathered, among others in the German ACOS registry24 and more recently in the quality‐control registry of the ALKK (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausärzte).25 Further, local patient samples were collected in the MONICA (Multinational MONItoring of trends and determinants in CArdiovascular disease)/KORA (KOoperative gesundheitsforschung in der Region Augsburg) studies,26 the Myocardial Infarction Network Essen,27 or the German Heart Centre ACS registry.28

However, with the exception of ACOS in 2002, none of these registries or observational studies investigated the special situation of patients in CR, in particular the outcomes that can be achieved during this period. In the present TROL registry, patients with STE‐ACS compared to NSTE‐ACS were younger and had fewer comorbidities, which is in line with previous findings.29 Despite limited differences in the prescription pattern of medications, a high proportion of patients of both groups received antiplatelet drugs, statins, and other cardiovascular medication. Clopidogrel was underused (overall 77% at entry and 76% at discharge), as dual antiplatelet therapy is an established standard in all patients with ACS.3, 4 About 10% of patients had oral anticoagulation, but at least at entry (within 4 weeks after the acute event), combined administration of oral anticoagulants, ASA, and clopidogrel are standard. Prescription rates of other cardiac medications increased substantially during the CR stay compared to the acute hospital stay. This finding underlines the importance of CR in initiating cardiovascular medications and titrating the doses if needed.

Due to the combination of optimized cardiovascular medication, exercise training, and further risk factor management, lipid values were substantially improved between CR entry and discharge, and the mean LDL‐C value of 85.5 mg/dL is substantially lower compared to the 2000 to 2005 values reported in the same setting.14 As a result, 75% of patients achieved the LDL‐C <100mg/dL target despite the relatively short CR duration. Notably, the ACS guidelines stipulate a lower target of <70 mg/dL, which should be achieved with statin‐based therapy,3, 4 and this goal was met by only 27.6% of patients at the end of the rehabilitation stay. Simvastatin was predominantly used, which can be explained as the reference drug in its class and by far the most frequently prescribed statin in Germany.30 The average simvastatin dose of 35 mg/d in TROL is in the medium range and probably indicates a concern for dose‐dependent risk of statin‐induced myopathy.31, 32 Instead of increasing statin doses, in our study physicians added a cholesterol absorption inhibitor in nearly a third of the cohort during the CR stay. A substantial body of evidence is available for the combination of simvastatin and cholesterol absorption inhibitor,33, 34 and as in other indications such as arterial hypertension or chronic heart failure, combination treatment appears adequate in patients who did not achieve their treatment targets on monotherapy. Increasing the number of medications could create problems with medication adherences as shown in many studies. Fixed combinations are likely beneficial, as increasing the number of daily medications, irrespective of drug class, likely create problems with medication adherence.35, 36

Methodological Aspects

Strengths of the TROL registry include the prospective design, the participation of many CR centers, which makes the registry representative for the German CR setting, and various quality measures (plausibility checks and others). However, in terms of weaknesses, the study was based on voluntary participation of the centers and selection bias cannot be excluded for physicians and patients (participants may be more adherent to therapy compared to those declining). Further, missing data or under‐reporting of characteristics may decrease robustness of results. The 3‐week CR period is not the key factor in treating in life‐long cardiovascular diseases. However, it is important because during this phase chronic treatments are initiated, and many family physicians will maintain the medication schedule of the CR period. We did not collect long‐term data on the follow‐up of patients in the primary care setting, with respect to lipid level attainment, future cardiovascular events, or survival, and cannot make statements about these outcomes.

Conclusion

We describe moderate differences between patients with STE‐ACS compared to NSTE‐ACS patients in terms of age and comorbidities, and drug treatment. The set of interventions applied during the CR stay improved lipid parameters, blood pressure, and exercise capacity. Thus, both patient groups had substantial benefit from the participation in the CR program.

Rona Reibis, MD, and Heinz Völler, MD, PhD contributed equally to this article.

The TROL registry was conducted in cooperation with the German Society for Prevention and Rehabilitation. The study was supported by MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Munich‐Haar, Germany. CJ and SKH are full‐time employees of MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH. The other authors have received consultancy honorarium from MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH.

The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland. Ten leading causes of mortality 2011 in Germany [Todesursachen: Sterbefälle insgesamt 2011 nach den 10 häufigsten Todesursachen der International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD‐10)]. https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Gesundheit/Todesursachen/Tabellen/SterbefaelleInsgesamt.html. Accessed December 21, 2013.

- 2. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2551–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2569–2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines . ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST‐segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2999–3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Terkelsen CJ, Lassen JF, Norgaard BL, et al. Mortality rates in patients with ST‐elevation vs. non‐ST‐elevation acute myocardial infarction: observations from an unselected cohort. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, et al. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2155–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fox KA, Carruthers KF, Dunbar DR, et al. Underestimated and under‐recognized: the late consequences of acute coronary syndrome (GRACE UK‐Belgian Study). Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2755–2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Balady GJ, Ades PA, Comoss P, et al. Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation Writing Group. Circulation. 2000;102:1069–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. West R. Contribution of cardiac rehabilitation in the management of patients following acute myocardial infarction. Future Cardiol. 2012;8:673–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bentley D, Khan S, Oh P, et al. Physical activity behavior two to six years following cardiac rehabilitation: a socioecological analysis. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36:96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lawler PR, Filion KB, Eisenberg MJ. Efficacy of exercise‐based cardiac rehabilitation post‐myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162:571–584.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Salzwedel A, Nosper M, Rohrig B, et al. Outcome quality of in‐patient cardiac rehabilitation in elderly patients—identification of relevant parameters [published online ahead of print November 20, 2012]. Eur J Prev Cardiol. doi: 10.1177/2047487312469475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jünger C, Rauch B, Schneider S, et al. Effect of early short‐term cardiac rehabilitation after acute ST‐elevation and non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction on 1‐year mortality. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:803–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bestehorn K, Wegscheider K, Voller H. Contemporary trends in cardiac rehabilitation in Germany: patient characteristics, drug treatment, and risk‐factor management from 2000 to 2005. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15:312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Prävention und Rehabilitation von Herz‐Kreislauferkrankungen e.V., Koblenz, Germany. http://www.dgpr.de. Accessed December 21, 2013.

- 16. Voller H, Reibis R, Pittrow D, et al. Secondary prevention of diabetic patients with coronary artery disease in cardiac rehabilitation: risk factors, treatment and target level attainment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:879–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Auer R, Gaume J, Rodondi N, et al. Efficacy of in‐hospital multidimensional interventions of secondary prevention after acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:3109–3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. West RR, Jones DA, Henderson AH. Rehabilitation after myocardial infarction trial (RAMIT): multi‐centre randomised controlled trial of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation in patients following acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2012;98:637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Parashar S, Spertus JA, Tang F, et al. Predictors of early and late enrollment in cardiac rehabilitation, among those referred, after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126:1587–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eggers KM, Kempf T, Venge P, et al. Improving long‐term risk prediction in patients with acute chest pain: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) risk score is enhanced by selected nonnecrosis biomarkers. Am Heart J. 2010;160:88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goodman SG, Huang W, Yan AT, et al. The expanded Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events: baseline characteristics, management practices, and hospital outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2009;158:193–201.e1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bueno H, Danchin N, Tafalla M, et al. EPICOR (long‐tErm follow‐up of antithrombotic management Patterns In acute CORonary syndrome patients) study: rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. Am Heart J. 2013;165:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lewis WR, Peterson ED, Cannon CP, et al. An Organized Approach to Improvement in Guideline Adherence for Acute Myocardial Infarction: Results With the Get With The Guidelines Quality Improvement Program. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1813–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bauer T, Hoffmann R, Junger C, et al. Efficacy of a 24‐h primary percutaneous coronary intervention service on outcome in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction in clinical practice. Clin Res Cardiol. 2009;98:171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schwarz AK, Zahn R, Hochadel M, et al. Age‐related differences in antithrombotic therapy, success rate and in‐hospital mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the quality control registry of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausarzte (ALKK). Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100:773–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kirchberger I, Meisinger C, Heier M, et al. Patient‐reported symptoms in acute myocardial infarction: differences related to ST‐segment elevation: the MONICA/KORA Myocardial Infarction Registry. J Intern Med. 2011;270:58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hailer B, Naber C, Koslowski B, et al. Gender‐related differences in patients with ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: results from the registry study of the ST elevation myocardial infarction network Essen. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ndrepepa G, Mehilli J, Schulz S, et al. Patterns of presentation and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Cardiology. 2009;113:198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abbott JD, Ahmed HN, Vlachos HA, et al. Comparison of outcome in patients with ST‐elevation versus non‐ST‐elevation acute myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Dynamic Registry). Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Klose G, Schwabe U. Lipid lowering drugs [Lipidsenkende Mittel]. In: Arzneiverordnungs‐Report 2011. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2010;682:665–680. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kashani A, Sallam T, Bheemreddy S, et al. Review of side‐effect profile of combination ezetimibe and statin therapy in randomized clinical trials. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1606–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Feng Q, Wilke RA, Baye TM. Individualized risk for statin‐induced myopathy: current knowledge, emerging challenges and potential solutions. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13:579–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ijioma N, Robinson JG. Lipid‐lowering effects of ezetimibe and simvastatin in combination. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2011;9:131–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lozano R, Marin R, Santacruz MJ, et al. Ezetimibe‐Simvastatin, a pharmacodynamic interaction? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:359–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bangalore S, Kamalakkannan G, Parkar S, et al. Fixed‐dose combinations improve medication compliance: a meta‐analysis. Am J Med. 2007:120:713–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Naderi SH, Bestwick JP, Wald DS. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: meta‐analysis on 376,162 patients. Am J Med. 2012:125:882–887.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]