ABSTRACT

Prevention of cardiovascular disease, undoubtedly an emphasis of clinical care in 2014, will provide both opportunities and challenges to patients and their healthcare providers. The recently‐released ACC/AHA guidelines on assessment of cardiovascular risk, lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk, management of overweight and obesity, and treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk, have introduced new concepts and revised prior conventional strategies. New to risk assessment are the Pooled Cohort Equations, targeting the expanded concept of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and focusing not solely on mortality but as well on major nonfatal events. The lifestyle management focuses on diet and physical activity for lipid and blood pressure control. The cholesterol guideline identifies four high‐risk groups with the greatest benefits from statin therapy: preexisting ASCVD, primary LDL‐C elevations ≥190 mm/dl, those 45–75 years with diabetes and LDL‐C 70–189 mm/dl without clinical ASCVD, and those 40–75 years without clinical ASCVD with an LDL‐C 70–189 mg/dl with a 7.5% or greater 10‐year ASCVD risk. Eliminated are arbitrary LDL‐C treatment targets, with individual patient risk status guiding who should take statins and the appropriate intensity of statin drugs. Patient‐physician discussions of individual benefits and risks are paramount. Management of high blood pressure remains controversial, with two different expert panels offering varying treatment targets; there is general agreement on a <140/90 mmHg goal, but substantial disagreement on blood pressure targets for older adults. Clinicians and their patients deserve a well‐researched concensus document.

INTRODUCTION

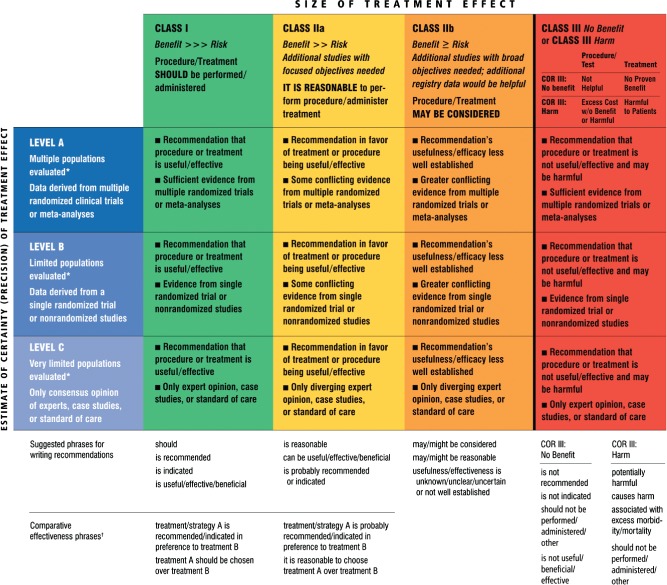

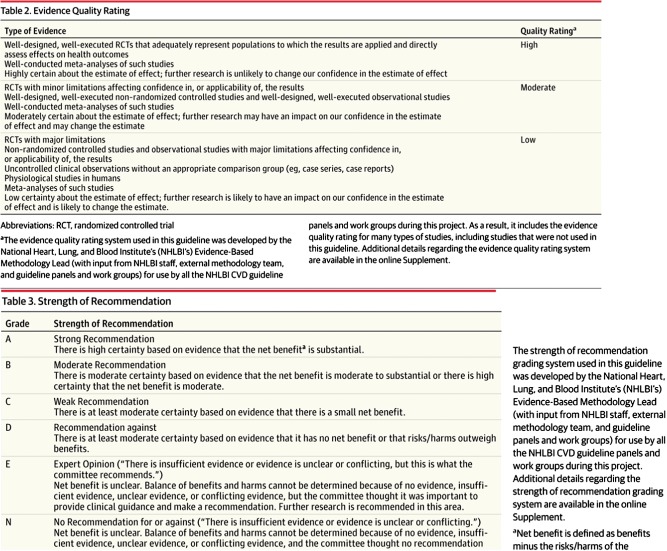

The year 2014 will likely focus substantially on cardiovascular risk assessment and preventive interventions, buttressed by requirements of the Affordable Care Act.1 Four recent and long‐awaited American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Guidelines provide the clinician with evidence‐based recommendations for Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk, 2 Lifestyle Management to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk, 3 Management of Overweight and Obesity, 4 and Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk.5 The recommendations are based on the highest quality evidence available, aggregated through 2011, and follow the ACC/AHA Class of Recommendation/Level of Evidence (COR/LOE) construct displayed in Figure 1. They are designed to align clinical preventive practice with the latest scientific evidence. Although not a formal guideline, the ACC/AHA/ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Science Advisory presents “An Effective Approach to High Blood Pressure Control.” 6 A second high blood pressure (BP) document, the 2014 Evidence‐Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults, a report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8) uses a different grading system for type of evidence and strength of recommendations (Figure 2 ).7 These BP recommendations differ in targets and therapeutic approaches and will require reconciliation. Because cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of mortality in the United States, 8 and these guidelines substantially impact clinical practice and focus the needs of most patients, I have chosen to highlight the pivotal recommendations and provide a brief commentary for each. My commentaries are indicated in italics, accompanying my abstracted Guideline recommendations.

Figure 1.

Applying classification of recommendation and level of evidence. *Data available from clinical trials or registries about the usefulness/efficacy in different subpopulations, such as sex, age, history of diabetes, history of prior myocardial infarction, history of heart failure, and prior aspirin use. A recommendation with level of evidence B or C does not imply that the recommendation is weak. Many important clinical questions addressed in the guidelines do not lend themselves to clinical trials. Although randomized trials are unavailable, there may be a very clear clinical consensus that a particular test or therapy is useful or effective. †For comparative effectiveness recommendations (class I and IIa, level of evidence A and B only), studies that support the use of comparator verbs should involve direct comparisons of the treatments or strategies being evaluated. Reproduced with permission from Goff et al.2

Figure 2.

Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8) grading system for quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Reproduced with permission from James et al.7

ASSESSMENT OF CARDIOVASCULAR RISK2

The basic paradigm of risk assessment involves matching the intensity of preventive efforts to an individual patient's absolute atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk. New to these guidelines are the Pooled Cohort Equations 9 for estimating ASCVD risk in primary prevention. These race‐ and sex‐specific equations are based on information derived from contemporary National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)‐sponsored cohort studies, including ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study), Cardiovascular Health Study, and CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults), combined with applicable data from the Framingham Original and Offspring Study cohorts. The term ASCVD adds stroke, as well as myocardial infarction (MI), to the risk calculation and focuses not solely on mortality but on major nonfatal events as well. Covariates in the equations included age, treated or untreated systolic blood pressure (SBP), total cholesterol and high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C) levels, current smoking status, and history of diabetes. Robust data are available only for non‐Hispanic African Americans and non‐Hispanic whites. Although considerable conversation has been generated by these equations, they more accurately identify the higher‐risk individuals more likely to benefit from statin therapy, and help initiate such discussions between clinicians and their patients. The threshold of a 10‐year 7.5% ASCVD risk identifies 1 of the 4 high‐risk groups likely to derive the greatest statin benefits. For healthy patients age 20 to 79 years, the first step is to assess ASCVD risk factors. Beginning at age 40, a formal estimation of the absolute 10‐year risk for ASCVD is recommended. Lifetime risk estimation is recommended for persons age 20 to 39 years and those age 40 to 59 years at low 10‐year risk, as a basis for applicable risk information and appropriate lifestyle counseling. If risk‐based treatment decisions remain uncertain, clinicians may use selected alternative risk markers to enhance treatment decisions. Recommendations are also provided for long‐term risk assessment. Healthcare organizations are recommended to convert to these new Pooled Cohort Equations as soon as practical. This new ASCVD Risk Estimator app is available online for both clinicians and patients. Review of emerging data may further refine risk stratification in future updates.

10‐Year Risk Assessment for a First Hard ASCVD Event (Nonfatal MI, Coronary Heart Disease Death, Fatal or Nonfatal Stroke)

Use race‐ and sex‐specific Pooled Cohort Equations in non‐Hispanic African Americans and non‐Hispanic whites, 40 to 79 years of age (class of recommendation [COR]: I, level of evidence [LOE]: B).

May consider these equations for non‐Hispanic whites in populations other than African Americans and non‐Hispanic whites (COR: IIb, LOE: C).

Use of Additional Risk Markers After Quantitative Risk Assessment

If risk‐based treatment decisions uncertain, may consider 1 or more of following: family history of premature ASCVD, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, coronary artery calcium score, ankle‐brachial index (COR: IIb, LOE: B).

Routine measurement of carotid intimal medial thickness not recommended in clinical practice (class III: no benefit, LOE: B).

Contributions to risk assessment of apolipoprotein B, chronic kidney disease (CKD), albuminuria, cardiorespiratory fitness uncertain at present; no recommendations for or against use.

Long‐term Risk Assessment

It is reasonable to assess traditional ASCVD risk factors every 4 to 6 years in adults 20 to 79 years old free of ASCVD and estimate 10‐year ASCVD risk (COR: IIa, LOE: B).

May consider assessing 30‐year or lifetime ASCVD risk based on traditional risk factors in adults 20 to 59 years old, free from ASCVD, and not at high short‐term risk (COR: IIb, LOE: C).

Lifestyle Management to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk3

Lifestyle measures are recommended for all patients and emphasize diet and physical activity.

Diet Recommendations for Low‐Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL‐C) Lowering: Advise Adults Who Would Benefit from LDL‐C Lowering to (COR: I, LOE: A)

Consume diet that emphasizes intake of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains; includes low‐fat dairy products, poultry, fish, legumes, nontropical vegetable oils and nuts; and limits intake of sweets, sugar‐sweetened beverages, and red meats.

Adapt diet to calorie requirements, personal and cultural food preferences, and nutrition therapy for other medical conditions (including diabetes mellitus).

Follow plans such as Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dietary pattern, US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Pattern, or American Heart Association (AHA) Diet.

Aim for a diet that achieves 5% to 6% of calories from saturated fat.

Reduce percent of calories from saturated fat and transfat.

Diet Recommendations for BP Lowering: Advise Adults Who Would Benefit From BP Lowering to

Consume diet that emphasizes intake of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains; includes low‐fat dairy products, poultry, fish, legumes, nontropical vegetable oils, and nuts; limits intake of sweets, sugar‐sweetened beverages, and red meats (COR: I, LOE: A).

Adapt diet to calorie requirements, personal and cultural food preferences, and nutritional therapy for other medical conditions (including diabetes mellitus) (COR: I, LOE: A).

Follow plans such as DASH dietary pattern, USDA Food Pattern, or AHA diet (COR: I, LOE: A).

Lower sodium intake (COR: I, LOE: A).

Consume no more than 2400 mg/d of sodium. Further reduction of sodium to 1500 mg/d can result in greater reduction in BP. Even reducing sodium intake by at least 1000 mg/d lowers BP (COR: IIa, LOE: B).

Combine DASH dietary pattern with lower sodium intake (COR: I, LOE: A).

The basic diets recommended for low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) lowering and BP lowering are identical, save for the addition of sodium restriction in the diet for BP lowering. This dietary concordance is helpful in clinical practice and for the many patients with both problems. Reduction of sodium intake by 1000 mg/d can reduce CVD events by approximately 30%.

Physical Activity Recommendations

Advise adults to engage in aerobic physical activity to reduce LDL‐C and non–HDL‐C: 3 to 4 sessions a week, average 40 minutes per session, involving moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity physical activity (COR: IIa, LOE: A).

Advise adults to engage in aerobic physical activity to lower BP: 3 to 4 sessions a week, average 40 minutes per session, involving moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity physical activity (COR: IIa, LOE: A).

Physical activity recommendations are comparable for reducing LDL‐C and lowering BP, again helpful for clinicians and patients. Note that current recommendations are not identical to the 2008 Federal physical activity guidelines, which targeted overall health, not solely LDL‐C or BP lowering.10, 11 Clinicians and patients would be helped by translation of these recommendations into steps/day (ie, the 10,000 steps/day goal) or measures enabling the use of simple personal activity‐tracker devices.

MANAGEMENT OF OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY IN ADULTS4

This is an update of the 1998 obesity guidelines, and is designed to help primary care physicians decide who should be recommended for weight loss and what health benefits can be anticipated. More than 78 million US adults were obese in 2009 to 2010, placing them at increased risk of morbidity from hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, gall bladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea and respiratory problems, and some cancers. Obesity is also associated with an increased risk of all‐cause and CVD mortality. Pharmacotherapy for weight loss is not addressed, but guidance is offered regarding bariatric surgery.

Identifying Patients Who Need to Lose Weight

Measure height and weight and calculate body mass index (BMI) at least annually (COR: I, LOE: C).

Use current cut points for overweight (BMI >25.0–29.9 kg/m2 ) and obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) to identify increased CVD risk. Use current cut point for obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) to identify increased risk of all‐cause mortality (COR: I, LOE: B)

The greater the BMI, the greater the risk of CVD, type 2 diabetes, and all‐cause mortality (COR: I, LOE: B).

Measure waist circumference at least annually in overweight and obese adults. The greater the waist circumference, the greater the risk of CVD, type 2 diabetes, and all‐cause mortality (COR: IIa, LOE: B).

Matching Treatment Benefits With Risk Profiles: Effect of Weight Reduction on CVD Risk Factors, Events, Morbidity, and Mortality

Lifestyle changes that produce even modest, sustained weight loss of 3% to 5% produce clinically meaningful health benefits. Greater weight loss produces greater benefit: meaningful reductions in triglycerides, blood glucose, hemoglobin A1C, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Greater weight loss further reduces BP, improves LDL‐C and HDL‐C, and reduces the need for medications to control BP, blood glucose, and lipids (COR: 1, LOE: A).

Diets for Weight Loss

Prescribe diet to reduce caloric intake as part of comprehensive lifestyle intervention using 1 of following:

1200 to 1500 kcal/d for women and 1500 to 1800 kcal/d for men.

500 kcal/d or 750 kcal/d energy deficit.

Evidence‐based diet that restricts certain food types (such as high‐carbohydrate foods, low‐fiber foods, or high‐fat foods) to create energy deficit by reduced food intake (COR: I, LOE: A).

Prescribe calorie‐restricted diet based on patient's preferences and health status and preferably refer to nutrition professional for counseling (COR: I, LOE: A).

Lifestyle Intervention and Counseling

Advise participation for ≥6 months in comprehensive lifestyle program that assists adherence to lower‐calorie diet and increased physical activity through behavioral strategies (COR: I, LOE: A).

Prescribe on‐site, high‐intensity (ie, ≥14 sessions in 6 months) comprehensive weight loss interventions by trained interventionist (COR: I, LOE: A).

Electronically delivered weight loss programs (including by telephone) that include personalized feedback may result in less weight loss than face‐to‐face interventions (COR: IIa, LOE: A).

Some commercially‐based programs that provide comprehensive lifestyle intervention are an option for weight loss, if there is peer‐reviewed published evidence of safety and efficacy (COR: IIa, LOE: A).

Use very low‐calorie diet (<800 kcal/day) only in limited circumstances provided by trained practitioners in a medical‐care setting. Medical supervision is required because of rapid weight loss and potential for health complications (COR: IIa, LOE: A).

Advise overweight and obese individuals who have lost weight to participate long term (≥1 year) in a comprehensive weight loss maintenance program (COR: I, LOE: A).

For weight loss maintenance, prescribe face‐to‐face or telephone‐delivered weight loss maintenance programs to help participants engage in high‐level physical activity (ie, 200 to 300 min/wk), monitor body weight regularly (weekly or more frequently), and consume reduced‐calorie diet (needed to maintain lower body weight) (COR: I, LOE: A).

Selecting Patients for Bariatric Surgical Treatment for Obesity

Advise adults with BMI ≥40, or BMI ≥35 with obesity‐related comorbid conditions, who have not responded to behavioral treatment with or without pharmacotherapy that bariatric surgery may be an appropriate option. Offer referral to experienced bariatric surgeon for consultation and evaluation (COR: IIa, LOE: A).

Insufficient evidence to recommend for or against bariatric surgical procedures with BMI <35.

Advise patients that choice of specific bariatric surgical procedure may be affected by patient factors, including age, severity of obesity/BMI, obesity‐related comorbid conditions, other operative risk factors, risk of short‐ and long‐term complications, behavioral and psychosocial factors, and patient tolerance for risk as well as provider factors (COR: IIb, LOE: C).

TREATMENT OF BLOOD CHOLESTEROL TO REDUCE ATHEROSCLEROTIC CARDIOVASCULAR RISK IN ADULTS5

New to this guideline is the elimination of arbitrary LDL‐C and/or non–HDL‐C treatment targets, a prominent feature of prior guidelines. Rather, it emphasizes individual patient risk assessment to determine who should take statins and guide the appropriate intensity of statin drugs to reduce ASCVD risk in individuals most likely to benefit. Statins are unequivocally identified as the therapy of choice for elevated cholesterol levels, and guidance is provided for high‐intensity vs moderate‐intensity statin use.

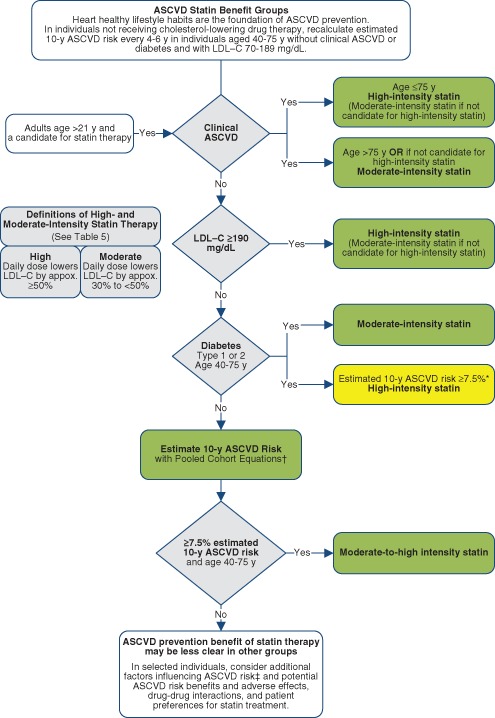

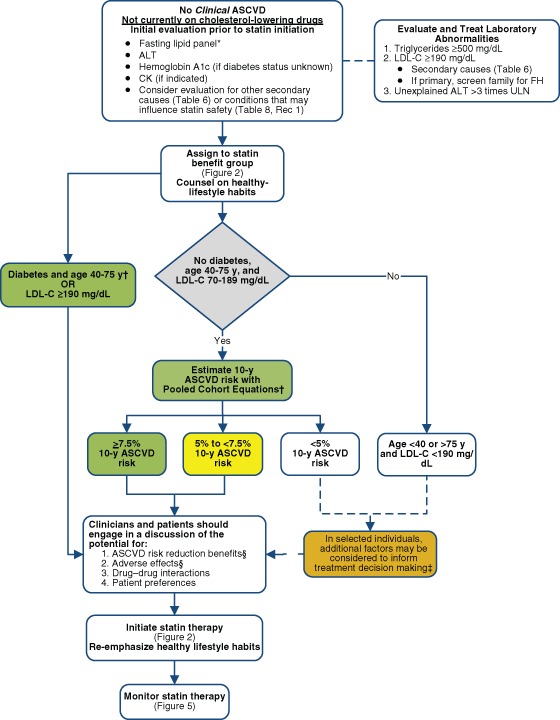

Statins are recommended via a streamlined algorithm (Figure 3 ), compared to Adult Treatment Panel III, for the secondary and primary prevention of ASCVD. Figure 3 is an evidence-based algorithm, identifying the groups of patients with greatest statin therapy benefits. For primary prevention patients, Figure 3 must be used in conjunction with Figure 4 , which highlights individualization of decision-making based on physician-patient discussions. Nonstatin therapies are not considered to provide acceptable ASCVD risk reduction.

Figure 3.

Evidence for major recommendations for statin therapy for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) prevention. Reproduced with permission from Stone et al.5

Figure 4.

Initiating statin therapy in individuals without clinical ASCVD. Reproduced with permission from Stone et al.5

Four high‐risk groups of patients are identified who have the greatest statin benefits in secondary and primary prevention:

Individuals with preexisting clinical ASCVD.

Individuals with primary elevations of LDL‐C ≥190 mg/dL.

Individuals age 40 to 75 years with diabetes and LDL‐C 70 to 189 mg/dL without clinical ASCVD.

Individuals without clinical ASCVD, 40 to 75 years of age with LDL‐C 70 to 189 mg/dL, with an estimated 10‐year ASCVD risk of 7.5% or higher.

Lifestyle modifications are recommended prior to and associated with cholesterol‐lowering therapies.

The guideline recommends use of the new Pooled Cohort Equations 9 to estimate 10‐year ASCVD risk in white and black men and women. Also new to the guideline is attention to the LDL ≥190 mg/dL (likely familial hypercholesterolemia) population.

Major recommendations for statin therapy for ASCVD prevention are diagrammed in Figures 3 and 4.

Treatment Targets

No sufficient evidence was identified to support the continued use of fixed LDL‐C and/or non–HDL‐C treatment targets. No recommendations were provided for or against specific LDL‐C or non–HDL‐C targets for primary or secondary prevention of ASCVD.

Secondary Prevention

Initiate or continue high‐intensity statin as first‐line therapy in women and men ≤75 years old with clinical ASCVD (COR: I, LOE: A) (Table 1).

When high‐intensity statin should be used but is contraindicated, or individuals are predisposed to statin‐associated adverse effects, moderate‐intensity statin should be used if tolerated (COR:I, LOE: A).

In individuals >75 years old with clinical ASCVD, it is reasonable to evaluate the potential for ASCVD risk‐reduction benefit and adverse effects, for drug‐drug interactions, and to consider patient preferences in initiating or continuing moderate‐ or high‐intensity statin use (COR: IIa, LOE: B).

Table 1.

High‐ Moderate‐ and Low‐Intensity Statin Therapy (Used in the Randomized Controlled Trials Reviewed by the Expert Panel)*

| High‐Intensity Statin Therapy | Moderate‐Intensity Statin Therapy | Low‐Intensity Statin Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Daily dose lowers LDL‐C, on average, by approximately ≥50% | Daily dose lowers LDL‐C, on average, by approximately 30% to <50% | Daily dose lowers LDL‐C, on average, by <30% |

| Atorvastatin (40†), 80 mg; Rosuvastatin 20 (40) mg | Atorvastatin 10 (20) mg, Rosuvastatin (5) 10 mg, Simvastatin 20–40 mg,‡ Pravastatin 40 (80) mg, Lovastatin 40 mg, Fluvastatin XL 80 mg, Fluvastatin 40 mg bid, Pitavastatin 2–4 mg | Simvastatin 10 mg, Pravastatin 10–20 mg, Lovastatin 20 mg, Fluvastatin 20–40 mg, Pitavastatin 1 mg |

Abbreviations: bid, twice daily; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol. Identified by symbols bold signifies RCTs used by Panel Italics and ( ) other doses. Reproduced with permission from Stone et al.5

Primary Prevention in Individuals ≥21 Years Old With LDL‐C ≥190 mg/dL

Evaluate individuals with LDL ≥190 mg/dL or triglycerides ≥500 mg/dL for secondary causes of hyperlipidemia (COR: I, LOE: B).

Treat with statin regardless of estimated 10‐year ASCVD risk. Use high‐intensity statin or maximum tolerated statin if unable to tolerate high‐intensity statin (COR: I, LOE: B).

It is reasonable to intensify statin to achieve at least 50% LDL‐C reduction (COR: IIa, LOE: B).

After maximum intensity statin achieved, may consider addition of non‐statin drug to further lower LDL‐C (COR: IIb, LOE: C).

Primary Prevention in Individuals With Diabetes Mellitus and With LDL‐C 70 to 189 mg/dL

Initiate or continue moderate‐intensity statin for adults 40 to 75 years old with diabetes mellitus (COR: I, LOE: A).

High‐intensity statin is reasonable for adults 40 to 75 years old with diabetes mellitus with ≥7.5% estimated 10‐year ASCVD risk (COR: IIa, LOE: B).

In adults with diabetes mellitus <40 or >75 years old, it is reasonable to evaluate potential for ASCVD benefit and adverse effects, drug‐drug interactions, and consider patient preferences when deciding to initiate, continue, or intensify statin (COR: IIa, LOE: C).

Primary Prevention in Individuals Without Diabetes Mellitus and With LDL‐C 70 to 189 mg/dL

Use Pooled Cohort Equations to estimate 10‐year ASCVD risk to guide initiation of statin (COR: 1, LOE: B).

Treat adults 40 to 75 years old with estimated 10‐year ASCVD risk ≥7.5% with moderate‐ to high‐intensity statin (COR: I, LOE: A).

Reasonable to offer treatment with moderate‐intensity statin to adults 40 to 75 years old with LDL‐C 70 to 189 mg/dL and without diabetes and estimated 10‐year ASCVD risk of 5% to <7.5% (COR: IIa, LOE: B).

Before initiating statin for primary prevention of ASCVD with LDL‐C 70 to 189 mg/dL but no clinical ASCVD or diabetes mellitus, it is reasonable to discuss potential for ASCVD risk‐reduction benefits and adverse effects, drug‐drug interactions, and patient preferences (COR: IIa, LOE: C).

In adults with LDL‐C <190 mg/dL not identified in a statin benefit group, or for whom after quantitative risk assessment a treatment decision is uncertain, may consider additional factors to inform treatment decision making. May consider statin therapy for primary prevention only after evaluating potential for ASCVD risk reduction benefits, adverse effects, drug‐drug interactions, and patient preferences (COR: IIb, LOE: C).

Heart Failure and Hemodialysis

No recommendations for initiation or discontinuation of statins in patients with New York Heart Association class II‐IV ischemic systolic heart failure or on maintenance hemodialysis because of insufficient information.

Recommendations further provide focused evidence‐based responses to frequently asked questions about cholesterol lowering: safety of statin use, nonstatin safety, monitoring and optimizing statin therapy, and addressing insufficient response to statins. Nonstatin therapies were not considered to provide acceptable ASCVD risk‐reduction benefit compared to their potential adverse effects in routine preventive care.

Summary: Statin Safety Recommendations

-

To maximize statin safety, base the appropriate statin and dose on patient characteristics, level of ASCVD risk, and potential for adverse effects. Use moderate‐intensity statin in individuals with characteristics predisposing to statin‐associated adverse effects, in whom a high‐intensity statin is otherwise recommended (COR: I, LOE: B).

Multiple or serious comorbidities, including impaired renal or hepatic function.

History of previous statin intolerance or muscle disorders.

Unexplained alanine transferase (ALT) elevations >3 times upper limit of normal (ULN).

Patient characteristics or concomitant use of drugs affecting statin metabolism.

Patients >75 years of age.

May modify decisions for higher‐intensity statin with history of hemorrhagic stroke and Asian ancestry.

Do not routinely measure creatine kinase (CK) in individuals receiving statin (COR: III no benefit, LOE: A).

Baseline CK measurement is reasonable for individuals at increased risk for adverse muscle events: history of statin intolerance, muscle disease, clinical presentation, or concomitant drugs that might increase myopathy risk (COR: IIa, LOE: C).

Reasonable to measure CK with muscle symptoms during statin therapy (COR: IIa, LOE: C).

Perform baseline measurement of ALT levels before initiating statin (COR: I, LOE: B).

Reasonable to measure hepatic function if symptoms suggest hepatotoxicity during statin therapy (COR: IIa, LOE: C).

May consider decreasing statin dose when 2 consecutive LDL‐C values <40 mg/dL (COR: IIb, LOE: C).

May be harmful to initiate simvastatin 80 mg daily or increase dose to 80 mg daily (COR: III harm, LOE: A).

Evaluate for new‐onset diabetes in individuals receiving statin per current diabetes screening guidelines. Encourage those who develop diabetes mellitus during statin therapy to adhere to heart‐healthy diet, engage in physical activity, achieve and maintain healthy body weight, cease tobacco use, and continue statin to reduce ASCVD risk (COR: I, LOE: B).

Reasonable to use caution in individuals taking any dose of statin >75 years old, taking concomitant medications that alter blood metabolism, taking multiple drugs, or taking drugs for conditions that require complex medication regimens (COR: IIa, LOE: C).

-

Reasonable to evaluate and treat muscle symptoms in statin‐treated patients according to the following algorithm (COR: IIa, LOE: B).

To avoid unnecessary statin discontinuation, obtain history of prior or current muscle symptoms to establish baseline before initiating statin.

If unexplained severe muscle symptoms or fatigue develop during statin therapy, promptly discontinue statin and address possibility of rhabdomyolysis by evaluating CK, creatinine, and urinalysis for myoglobinuria.

If mild to moderate muscle symptoms develop during statin therapy, discontinue statin until problem can be evaluated; evaluate patient for other conditions that increase risk for muscle symptoms. If muscle symptoms resolve and no contraindication exists, give patient original or lower dose of same statin to establish causal relationship between muscle symptoms and statin therapy. If causal relationship exists, discontinue original statin; once muscle symptoms resolve, use low dose of different statin. Once low‐dose statin is tolerated, gradually increase the dose. If after 2 months without statin treatment muscle symptoms or elevated CK levels do not resolve completely, consider other causes of muscle symptoms. If persistent muscle symptoms determined to arise from a condition unrelated to the statin, resume statin at the original dose.

For individuals with confusional state or memory impairment on statin, reasonable to evaluate patient for nonstatin causes, in addition to possibility of statin adverse effects (COR: IIb, LOE: C).

Summary: Nonstatin Safety Recommendations

Safety of Niacin

Obtain baseline liver transaminases, fasting blood glucose or hemoglobin A1c, and uric acid before initiating niacin, during up‐titration and every 6 months thereafter ((COR: I, LOE: B).

-

Niacin should not be used if (COR III harm, LOE: B)

Transaminase elevations are >2 to 3 times ULN.

Persistent severe cutaneous symptoms, persistent hyperglycemia, acute gout, unexplained abdominal pain, or gastrointestinal symptoms occur.

New‐onset atrial fibrillation or weight loss occurs.

Reconsider the potential for ASCVD benefits and adverse effects before reinitiating niacin with niacin adverse effects (COR: I, LOE: B).

To reduce the frequency and severity of adverse cutaneous symptoms, reasonable to start niacin at a low dose and titrate to a higher dose, take niacin with food, or premedicate with aspirin to alleviate flushing (COR: IIa, LOE: C).

Safety of Bile Acid Sequestrants

Do not use bile acid sequestrants (BAS) with baseline fasting triglyceride ≥300 mg/dL or type II hyperlipoproteinemia, because severe triglyceride elevations might occur (COR: III harm, LOE: B).

Reasonable to use BAS with caution if baseline triglyceride level is 250 to 299 mg/dL; evaluate fasting lipid panel in 4 to 6 weeks. Discontinue BAS if triglycerides exceed 400 mg/dL (COR: IIa, LOE: C).

Safety of Cholesterol‐Absorption Inhibitors

Reasonable to obtain baseline hepatic transaminases before initiating ezetimibe. When ezetimibe coadministered with statin, monitor transaminase levels as clinically indicated and discontinue ezetimibe if persistent ALT elevations are >3 times ULN (COR: IIa, LOE B).

Safety of Fibrates

Do not initiate gemfibrozil in patients on statin because of increased risk for muscle symptoms or rhabdomyolysis (COR: III Harm, LOE: B).

May consider fenofibrate concomitantly with low‐ or moderate‐intensity statin only if benefits from ASCVD risk reduction or triglyceride lowering when triglycerides >500 mg/dL outweigh potential for adverse effects (COR: IIb, LOE: C).

-

Evaluate renal status before fenofibrate initiation, within 3 months after initiation, and every 6 months thereafter. Assess renal safety with both serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) based on creatinine (COR: I, LOE: B).

Do not use fenofibrate if moderate or severe renal impairment, eGFR <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (COR: III harm, LOE: B).

If eGFR is 30 to 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, fenofibrate dose should not exceed 54 mg/d (COR: III harm, LOE: B).

Discontinue fenofibrate if eGFR decreases persistently to ≤30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (COR: III harm, LOE: B).

Safety of Omega‐3 Fatty Acids

If eicosapentaenoic acid and/or docosahexaenoic acid are used for management of severe hypertriglyceridemia (triglycerides ≥500 mg/dL), reasonable to evaluate patient for gastrointestinal disturbances, skin changes, and bleeding (COR: IIa, LOE: B).

Recommendations for Monitoring, Optimizing, and Insufficient Response to Statin Therapy

Monitoring Statin Therapy

Regularly assess adherence to medication and lifestyle, therapeutic response to statin and safety. Perform fasting lipid panel 4 to 12 weeks after initiation for dose adjustment and every 3 to 12 months thereafter along with other safety measures as clinically indicated (COR: I, LOE: A).

Optimizing Statin Therapy

Use maximum tolerated statin intensity in individuals for whom high‐ or moderate‐intensity statin is advised but not tolerated (COR: I, LOE: B).

Insufficient Response to Statin Therapy

With less‐than‐desired therapeutic response or intolerance of recommended statin intensity, reinforce medication adherence, adherence to intensive lifestyle changes, and exclude secondary causes of hyperlipidemia (COR: I, LOE: A).

-

Reasonable to use following as desirable therapeutic response to recommended statin intensity (COR: IIa, LOE: B):

Approximately ≥50% LDL‐C reduction with clinical ASCVD or LDL‐C ≥190 mg/dL

Approximately 30% to 50% LDL‐C reduction without clinical ASCVD or LDL‐C 70 to 189 mg/dL

May consider addition of nonstatin cholesterol‐lowering drug in individuals at higher ASCVD risk taking maximum tolerated statin intensity who have less‐than‐desired therapeutic response if ASCVD risk‐reduction benefits outweigh potential for adverse effects. High‐risk individuals include secondary prevention patients <75 years old, patients with baseline LDLC >190/mg/dL, and patients 40 to 75 years old with diabetes mellitus (COR: IIb, LOE: C).

Reasonable to use nonstatin cholesterol‐lowering drugs shown to reduce ASCVD events in candidates for statin treatment who are completely statin intolerant, if ASCVD risk‐reduction benefits outweigh potential for adverse effects (COR: IIa, LOE: B).

APPROACHES TO BP CONTROL

An Effective Approach to BP Control6

A Science Advisory from the AHA/ACC/CDC presents a Hypertension Treatment Algorithm 6 for the nearly 78 million US adults with hypertension, which is a major modifiable risk factor for other cardiovascular diseases and stroke.8 The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data state that only 81.5% of those with hypertension are aware of their problem, 74.9% are being treated, but only 52.5% have BP control.12, 13 System‐level approaches are needed to combat this major, poorly controlled health threat.

-

For most people, the BP goal is <140/<90 mm Hg.

Lower targets may be appropriate for some populations with hypertension.

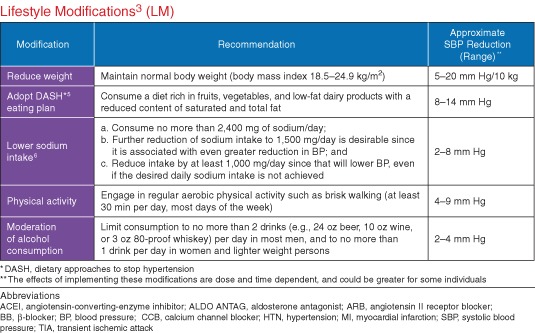

Lifestyle modifications should be initiated in all patients (Figure 5).

Self‐monitoring is encouraged for most patients.

-

Suggested medications for treatment of hypertension in the presence of certain medical conditions include:

Coronary artery disease/post‐MI: β‐blocker (BB), angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI).

Systolic heart failure: ACEI or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), BB, aldosterone antagonist, thiazide.

Diastolic heart failure: ACEI or ARB, BB, thiazide.

Diabetes: ACEI or ARB, thiazide, BB, calcium channel blocker (CCB).

Kidney disease: ACEI or ARB.

Stroke or transient ischemic attack: thiazide, ACEI.

Figure 5.

Lifestyle modifications. Reproduced with permission from Go et al.6

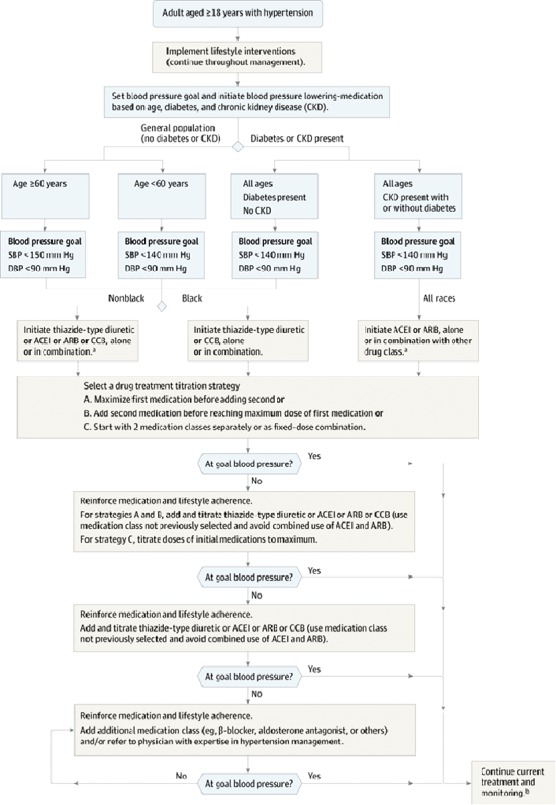

2014 Evidence‐Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults—Report from the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8)7

JNC8 identified strong evidence to support treating hypertensives ≥age 60 years old to a BP goal of <150/90 mm Hg and hypertensives 30 to 59 years old to a diastolic BP goal of <90 mm Hg. They found insufficient evidence for a systolic BP goal in hypertensive persons age <60 years or a diastolic BP goal in those age <30; a recommendation based on expert opinion was for a BP of <140/90 mm Hg for these groups. JNC8 recommended the same thresholds and goals for hypertensive adults with diabetes or nondiabetic CKD as for the general hypertensive population <60 years old. A change from the prior guideline was moderate evidence supporting initiating drug treatment with an ACEI, ARB, CCB. or thiazide‐type diuretic in non‐black hypertensives, including those with diabetes. For black hypertensives, including those with diabetes, a CCB or thiazide‐type diuretic is the recommended initial therapy. Finally, JNC8 identified moderate evidence supporting initial or add‐on hypertensive therapy with an ACEI or ARB to improve kidney outcomes in individuals with CKD.

The 2014 Hypertension Guideline (JNC8) used different gradations of quality rating (their Table 2) and strength of recommendation (their Table 3) than was used in the previously reviewed guidelines (Figure 2 ).

Nine specific recommendations are incorporated in a management algorithm (Figure 6 ):

General population ≥60 years old: initiate pharmacologic treatment to lower BP at SBP ≥150 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg and treat to goal SBP <150 mm Hg and DBP <90 mm Hg (Strong Recommendation, Grade A).

General population <60 years old: initiate pharmacologic treatment to lower BP at DBP ≥90 mm Hg and treat to goal DBP <90 mm Hg (ages 30–59 years, Strong Recommendation, grade A; ages 18–29 years, Expert Opinion, Grade E).

General population <60 years old: initiate pharmacologic treatment to lower BP at SBP ≥140 mm Hg and treat to goal SBP <140 mm Hg (Expert Opinion, Grade E).

Population ≥18 years old with CKD: initiate pharmacologic treatment to lower BP at SBP ≥140 mm Hg or DBP ≥90 mm Hg and treat to goal SBP <140 mm Hg and DBP ≤ 90 mm Hg (Expert Opinion, Grade E).

Population ≥18 years old with diabetes: initiate pharmacologic treatment to lower BP at SBP ≥140 mm Hg or DBP ≥90 mm Hg and treat to goal SBP <140 mm Hg and DPB <90 mm Hg (Expert Opinion, Grade E).

General nonblack population, including those with diabetes: initial hypertensive treatment to include thiazide‐type diuretic, CCB, ACEI, or ARB (Moderate Recommendation, Grade B).

General black population, including those with diabetes: initial antihypertensive treatment should include a thiazide‐type diuretic or CCB (for general black population: Moderate Recommendation, Grade B; for black patients with diabetes: Weak Recommendation, Grade C).

Population ≥18 years old with CKD, regardless of race or diabetes status: initial or add‐on antihypertensive treatment to include an ACEI or ARB to improve kidney outcomes (Moderate Recommendation, Grade B).

Main objective of treatment is to attain and maintain goal BP. If goal BP is not reached within 1 month of treatment, increase dose of initial drug or add second drug from 1 of classes in recommendation (see Figure 6). Adjust regimen until goal BP is reached; if it cannot be accomplished with 2 drugs, add and titrate third drug. Do not use ACEI and ARB together in same patient. If goal BP cannot be reached using only drugs in recommendation, an antihypertensive drug from other classes can be used. Consider referral to hypertension specialist if goal BP cannot be attained using above strategies (Expert Opinion, Grade E).

Figure 6.

Hypertension treatment algorithm. Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SDP, systolic blood pressure. Reproduced with permission from James et al.7

These 2 BP documents differ substantially in regard to treatment goals and strategies, particularly with disagreements as to the evidence for BP targets in older adults. Apparently there was significant lack of unanimity among the JNC8 authors. Clinicians and their patients deserve a well‐researched consensus document, and are unlikely to substantially alter their current practices prior to the promised 2015 blood pressure guideline update.

SUMMARY

Many important clinical questions addressed by these guidelines do not lend themselves to clinical trials. This highlights a limitation of these guidelines, which were informed predominantly by randomized clinical trials. Forthcoming updates derived from other data sources may fill in some gaps. As an example, the addition of alternative risk markers to guide treatment decisions is likely to expand as data from recent studies of these variables are incorporated in the risk calculations. Clinical trials reported subsequent to 2011 will add contemporary information.

The Pooled Cohort Equations for risk add stroke events to coronary heart disease events, (ie, expanding the ASCVD composite) and include serious nonfatal outcome events as well as mortality. Addition of the ASCVD Risk Estimator to the major electronic medical record system will provide the automation needed to encourage its use. This initial iteration, heavily influenced by NHLBI study data, may subsequently be modified with consideration of a broader range of newer evidence. Nonetheless, addressing composite ASCVD risk translates into the promise of reducing the looming US burden of disability and death from ASCVD.

References

- 1. Affordable Care Act . http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/rights/law/index.html.

- 2.Goff DC Jr, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines [published online ahead of print November 12, 2013]. Circulation. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/early/2013/11/11/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98.full.pdf+html?sid=53af8168‐4e81‐45f3‐81dc‐7771aff9d486. Accessed November 13, 2013.

- 3.Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines [published online ahead of print November 12, 2013]. Circulation. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/early/2013/11/11/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1.full.pdf+html?sid=cd51c796‐e2cf‐479c‐bba7‐4f460a178bf6. Accessed November 13, 2013.

- 4. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and The Obesity Society [published online ahead of print November 12, 2013]. Circulation. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/early/2013/11/11/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. Accessed November 13, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines [published online ahead of print November 12, 2013]. Circulation. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/early/2013/11/11/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a.full.pdf+html?sid=5234c4f1‐8a37‐403a‐a692‐126b367cfcab. Accessed November 13, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Go AS, Bauman MA, King MBS, et al. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [published online ahead of print November 15, 2013]. Hypertension. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000003. http://hyper.ahajournals.org/content/early/2013/11/14/HYP.0000000000000003.citation. Accessed November 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence‐based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults. Report from the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) [published online ahead of print December 18, 2013]. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427. Accessed December 18, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Risk Assessment Working Group . Pooled cohort risk assessment equations. http://www.cardiosource.org/science‐and‐quality/ practice‐guidelines‐and‐quality‐standards/2013‐prevention‐guideline‐tools.aspx.

- 10. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee . Physical Activity Guidelines Committee Report, 2008. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Egan BM, Li J, Qanungo S, Wolfman TE. Blood pressure and cholesterol control in hypertensive hypercholesterolemic patients: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 1988‐2010. Circulation. 2013;128:29–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Racial/ethnic disparities in the awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension—United States, 2003‐2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:351–355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]