Abstract

A recurrent de novo missense variant in KCNC1, encoding a voltage‐gated potassium channel expressed in inhibitory neurons, causes progressive myoclonus epilepsy and ataxia, and a nonsense variant is associated with intellectual disability. We identified three new de novo missense variants in KCNC1 in five unrelated individuals causing different phenotypes featuring either isolated nonprogressive myoclonus (p.Cys208Tyr), intellectual disability (p.Thr399Met), or epilepsy with myoclonic, absence and generalized tonic‐clonic seizures, ataxia, and developmental delay (p.Ala421Val, three patients). Functional analyses demonstrated no measurable currents for all identified variants and dominant‐negative effects for p.Thr399Met and p.Ala421Val predicting neuronal disinhibition as the underlying disease mechanism.

Introduction

Epilepsy and intellectual disability (ID) are common neuropsychiatric disorders with an approximate prevalence of 0.3 to 2%.1, 2, 3, 4 A subgroup of cases is due to pathogenic variants in potassium channels, which, however, might also present with a range of additional neurological features, such as ataxia.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 The potassium channel subfamily KV3 consists of four subunits (KV3.1, KV3.2, KV3.3, and KV3.4) which are encoded by KCNC1, KCNC2, KCNC3, and KCNC4.10 Mutations in KCNC3 are a well‐established cause of spinocerebellar ataxia type 13, whereas KCNC2 and KCNC4 have so far not been associated with human disease.8, 9

The evolutionarily highly conserved voltage‐gated potassium channel KV3.1 is predominantly expressed in fast‐spiking neurons to enable high‐frequency firing by fast channel activation and membrane repolarization.10 Fast‐spiking neurons include GABAergic interneurons in the neocortex and hippocampus, Purkinje cells in cerebellum, and neurons in central auditory nuclei.10, 11 To date, only one recurrent de novo missense variant in KCNC1 (c.959G > A, p.Arg320His) has been reported as a cause of progressive myoclonus epilepsy and ataxia (MEAK; OMIM #616187). The respective phenotype is similar to Unverricht‐Lundborg disease.12, 13, 14, 15 Subsequently, one nonsense variant (c.1015C > T, p.Arg339*) has been identified in three affected members of single family with ID without seizures.16 Here, we report three new pathogenic de novo missense variants in KCNC1 in five unrelated patients. The provided clinical information adds to the phenotypic delineation of KCNC1‐related disease.

Patients, Materials, and Methods

Clinical and genetic investigations

Patients were evaluated by neurologists and referred for diagnostic whole exome sequencing (WES) at different centers. The methods for WES and Sanger sequencing have been previously described.17, 18 Written informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all patients or their parents.

Functional analysis

The functional evaluation of identified KCNC1 variants was performed using two‐electrode voltage‐clamp recordings as previously described.13 Briefly, the three missense variants were introduced in the human KCNC1 cDNA (NM_004976) cloned in a pCMV Entry Vector (OriGene Technologies, USA) using the Quick Change Method (Stratagene, USA). The plasmids were linearized and in vitro transcription was performed using T7 RNA Polymerase (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany). Xenopus laevis oocytes (EcoCyte Bioscience, Germany) were washed in OR2 and incubated in Barth solution with gentamycin. Fifty‐nanoliters of cRNA (2 µg/µL) was injected using Robooinject® (Multichannel Systems, Germany) and stored at 16°C. Potassium currents were recorded after 2–3 days at room temperature (21–23°C) on Roboocyte2® (Multichannel Systems, Germany). Data analysis and graphical illustrations were achieved using Roboocyte2+ (Multichannel Systems, Germany), Excel (Microsoft, USA), and Graphpad Software (GraphPad Software, USA). Statistical evaluation for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05) was conducted using one‐way ANOVA on ranks with Dunn's post hoc test.

Results

Genetic testing

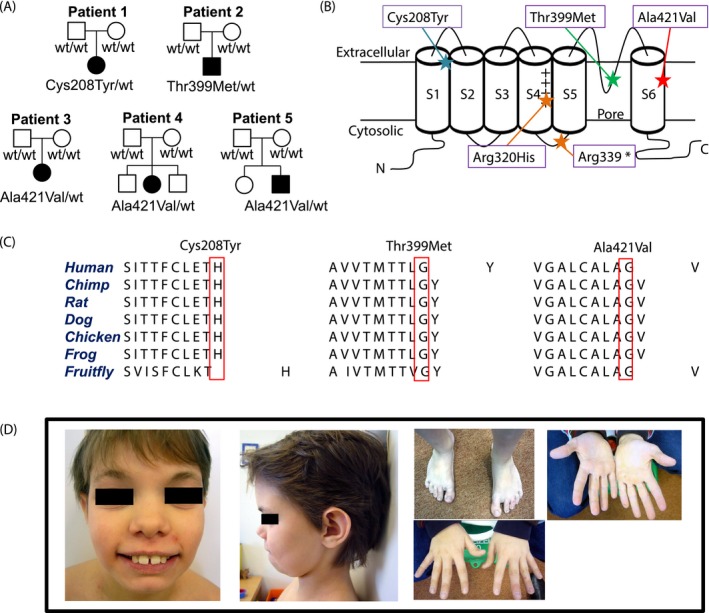

WES revealed three different heterozygous missense variants in KCNC1 (NM_001112741.1) in five unrelated patients. Patient 1 carries c.623G > A, p.Cys208Tyr, patient 2 c.1196C > T, p.Thr399Met, and patients 3, 4, and 5 c.1262C > T, p.Ala421Val. All variants are absent from public databases [1000 Genomes project, Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD 2.0.2), Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC 0.3.1)]. In line with a postulated de novo status, none of the variants was detected in DNA extracted from parental whole blood (Fig. 1A). Additional rare variants identified in patients 1, 2, and 3 are provided in Table S1. We cannot entirely rule out a potential contribution of these changes to the observed phenotypes. However, to the best of our knowledge there is currently no evidence supporting a functional relevance and putative disease association of these additional changes.

Figure 1.

(A) Pedigrees of the five unrelated affected individuals (closed symbols) with de novo KCNC1 variants and status of healthy family members (open symbols). wt indicates for wild type. (B) Graphical illustration of the KV3.1 channel demonstrates the domain structures. The positions of the identified variants (Cys208Tyr, Thr399Met, Ala421Val) and the previously published variants (Arg320His and Arg339*) are highlighted with stars. The plus sign illustrates the positively charged arginine in the voltage‐sensing S4 segment.21 (C) Amino acid sequences across different species indicate that the variants are localized in highly conserved regions. (D) Images of patient 2 at 11 years of age show hypertelorism, long palpebral fissures, broad nose, large ears, diastema, small chin, and sandal gap. The hands of patient 2 do not have any dysmorphic features.

Clinical phenotypes

Patient 1 (Cys208Tyr)

A 23‐year‐old German woman reported that mild tremor‐like symptoms began on both hands at the age of 2 years. Her psychomotor development was normal. Neurological examination revealed mild and nonprogressive constant high‐frequency action and postural myoclonus (or irregular tremor) on both arms with dystonic features on the right hand and arm with constant hyperextension of the fourth and fifth finger and reduced arm swing during gait (Video S1). The patient initially received diagnostics and various treatments for tremor without success (see below), and the quite jerky aspect of the irregular movements is more reminiscent of myoclonus in our opinion. An electromyographical (EMG) recording which might have helped to distinguish between tremor and myoclonus has not been performed. Copper metabolism, F‐dopa PET, and MRI scans of the brain and multiple EEG recordings were normal. Treatment trials with beta blockers, levodopa, and primidone were unsuccessful. Epileptic seizures were not reported.

Patient 2 (Thr399Met)

An 18‐year‐old German male works in a sheltered workshop and shows some articulation difficulties. When he was last examined at the age of 11 years, he was attending special school. He was diagnosed with mild to moderate intellectual disability and showed behavioral abnormalities, for example, difficulties socializing with other children. Motor development was slightly delayed, but his language was severely affected with first words by the age of 5 years. Dysmorphic features are shown in Figure 1D. There were neither congenital malformations nor any reported seizures. Neurological examination was unremarkable. EEG and MRI scan of the brain were normal.

Patient 3 (Ala421Val)

Patient 3 is a 5‐year‐old Croatian female in whom seizures (focal onset impaired awareness seizures, tonic‐clonic and myoclonic seizures) were first noted at 5 months of age and occurred up to 40 times per day. First generalized tonic‐clonic seizures started at the age of 2 years. Treatments with levetiracetam, zonisamide, and carbamazepine were unsuccessful. Finally, a combination therapy with clobazam and topiramate reduced her seizure frequency to 1–2 per month. She had global developmental delay and mild gait ataxia, which was so far nonprogressive. The EEG showed multifocal epileptic discharges and irregular spike‐wave complexes with polyspikes followed by bilateral synchronic 2/s spike‐wave activities. Cerebral MRI was normal.

Patient 4 (Ala421Val)

Patient 4, a 2‐year‐old female of Turkish origin, first presented with febrile seizures 3 weeks after birth. Seizures then occurred 15–35 times per day and lasted for 5–35 sec with even higher seizure frequencies during episodes with high fever, which did not respond to levetiracetam or valproate. She mostly had myoclonic absence seizures (Video S1), and less frequently myoclonic seizures without impaired awareness or absence seizures without myoclonus. During the myoclonic absence seizure, her eyes rolled upwards and both her proximal arms twitched for a few seconds. Her global development was delayed. She is now able to walk and vocalize but does not speak. Twenty‐four‐hour‐EEG showed normal background activity and multiple seizure episodes with rhythmic bifrontal 2–3/s spike‐wave discharges for 6–20 sec. Cerebral MRI was unremarkable (Fig. S2).

Patient 5 (Ala421Val)

This 2‐year‐old Chinese‐French male showed first myoclonic seizures at 5 months of age. The initial seizure frequency was 1–2 per day, which increased to 60–70 per day after 4 months. Treatment with valproate, levetiracetam, and clonazepam reduced his seizure frequency dramatically to once per month. He had predominantly myoclonic absence seizures (Video S1 with face covered) presenting with rapid eyelid myoclonia accompanied by twitching of proximal arms. The myoclonus was mostly on the left side, but occasionally occurred on both arms. In addition, he also had absences without myoclonus lasting for approximately 10 sec. At 8 months, he had two generalized tonic‐clonic seizures. The EEG showed episodes with generalized rhythmic discharges of 2–4 Hz, sometimes only as waves, sometimes as spike‐waves, lasting up to 15 sec and often accompanied by myoclonic movements visible in the electromyographic trace (Fig. S3). His development was delayed; he is now able to speak ten simple words, but cannot stand alone without any help. Cerebral MRI did not show any abnormalities.

Functional consequences of KCNC1 variants

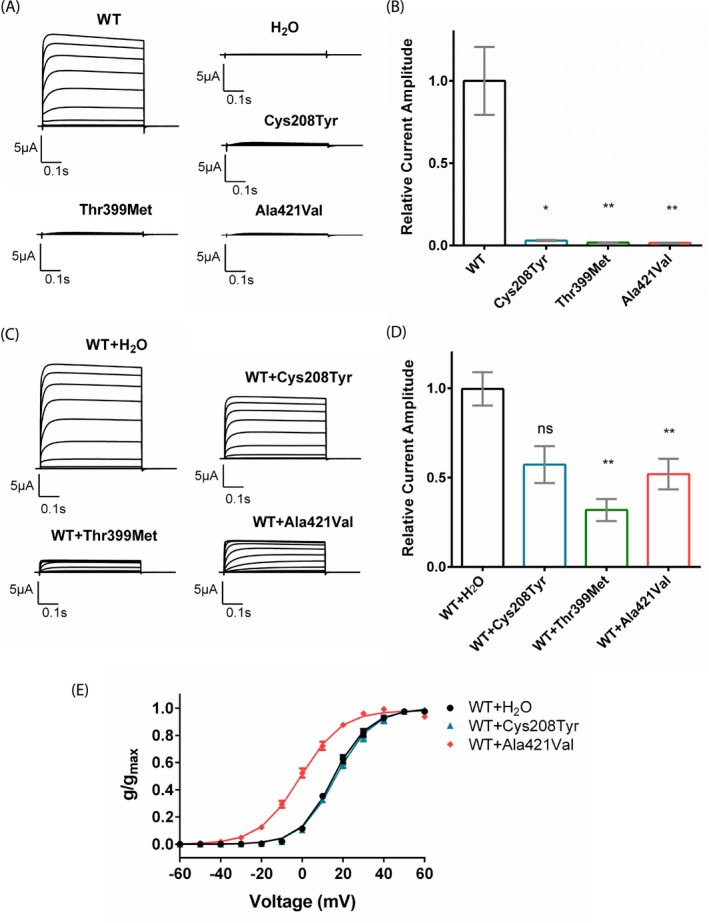

Current amplitudes recorded in oocytes expressing either of the three mutant channels were barely detectable and similar to water‐injected controls (Fig. 2A and 2). Coexpression of wild type (WT) with mutant channels indicated dominant‐negative loss‐of‐function effects with a significant decrease in K+ current amplitudes of approximately 68% and 48% for Thr399Met and Ala421Val mutant channels compared to WT alone (Fig. 2C and D), whereas coexpression of Cys208Tyr mutant and WT channels did not cause a significant amplitude reduction. The activation curve showed a hyperpolarizing shift when WT channels were coexpressed with Ala421Val mutant channels in comparison to WT channels alone (Fig. 2E), whereas Cys208Tyr channels did not show any significant difference. Thr399Met showed a strong dominant‐negative effect on the WT which impeded the evaluation of further gating parameters.

Figure 2.

Functional consequences of the identified KCNC1 variants. (A) Representative traces of KV3.1 currents recorded in Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing the wild type (WT) and the single‐site variants (Cys208Tyr, Thr399Met, Ala421Val) in response to the voltage steps from − 60 mV to + 60 mV. (B) Relative current amplitudes of oocytes injected with the WT (n = 23), Cys208Tyr (n = 8), Thr399Met (n = 14), and Ala421Val (n = 8) mutant channels (Dunn’s test, P < 0.05). Mean current amplitudes of currents elicited by a + 40 mV voltage step were analyzed between 0.4 and 0.5 msec and normalized to the mean value of WT channels recorded on the same day. (C) Representative current traces recorded in oocytes that were coinjected with WT cRNA and either water or a mutant cRNA in a 1:1 ratio. (D) Relative current amplitudes recorded from oocytes coexpressing WT and mutant channels (WT + H2O (n = 36), WT + Cys208Tyr (n = 8), WT + Thr399Met (n = 6), WT + Ala421Val (n = 27)) were normalized to the mean current amplitude of oocytes coinjected with the WT channel and water recorded on the same day (Dunn's test, P < 0.05). (E) Mean voltage‐dependent activation of KV3.1 channel for WT (n = 20), WT + Cys208Tyr (n = 5) and WT + Ala421Val (n = 10) channels. Lines illustrate Boltzmann Function fit to the data points. The activation curve of WT + Ala421Val channels showed a significant shift to more hyperpolarized potentials in comparison to WT channels alone. All data are shown as means ± SEM. The following symbols were used for statistical differences: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 and ns for not significant.

Discussion

We here identified three new de novo missense variants in KCNC1 in five unrelated individuals presenting with different clinical phenotypes compared to previously reported KCNC1 patients. Patient 1 (Cys208Tyr) exhibited nonprogressive, relatively mild, action‐induced myoclonus (or irregular tremor) as the only clinical sign without any cerebellar, epileptic, or cognitive symptoms. In contrast, MEAK patients (Arg320His) had a more severe and progressive action‐induced myoclonus, epilepsy, and ataxia leading to wheelchair dependency in 11 of 22 published patients by the age of approximately 17 years.13, 14, 15 The phenotype of patient 2 (Thr399Met), who showed ID and dysmorphic features, is more similar to the family reported by Poirier et al. in which three affected members carried the nonsense mutation Arg339*.16 All three had similar dysmorphic features, which however differed from those observed in patient 2 (Fig. 1D, Table 1). Compared to MEAK patients, also the three unrelated patients (3, 4, and 5) carrying the Ala421Val variant presented with different symptoms, neither showing myoclonus, but myoclonic and absence seizures and developmental delay. The presence of ataxia is difficult to judge as all three are still very young. While this study was underway, the change Ala421Val has been submitted to ClinVar by another group, indicating that it might represent a more frequent recurrent cause of ID and seizures.19

Table 1.

Clinical features of KCNC1 patients

| This publication | This publication | This publication | This publication | This publication | MEAK patients13, 14, 15 | Poirier et al. 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | 22 cases | 3 cases |

| Variant | c.623G > A, p.Cys208Tyr | c.1196C > T, p.Thr399Met | c.1262C > T, p.Ala421Val | c.1262C > T, p.Ala421Val | c.1262C > T, p.Ala421Val | c.959G > A, p.Arg320His | c.1015C > T, p.Arg339* |

| Inheritance | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo (14), 3 families (8) | Paternal |

| Age at onset (current age) | 2 years (23 years) | 1–2 years (18 years) | 5 months (5 years) | 3 weeks (2 years) | 5 months (2 years) | 3–15 years | 1–2 years |

| First sign | Myoclonus or "tremor" | Developmental delay | Myoclonic seizures | Febrile seizures | Myoclonic seizures | Myoclonus or "tremor" | Developmental delay |

| Seizures | No | No | Tonic‐clonic, focal onset impaired awareness, myoclonic, generalized | Myoclonic absence, myoclonic, absence | Myoclonic absence, absence, generalized | Tonic‐clonic, myoclonic, generalized | No |

| Action‐induced Myoclonus | Mild, nonprogressive | No | No | No | No | Severe, progressive | No |

| EEG | Normal | Normal | Normal background, irregular spike‐wave activity with polyspikes and rhythmic generalized 2 Hz spike‐waves | Normal background activity, generalized 2–3 Hz spike‐wave discharges | Normal background, generalized 2–4 Hz rhythmic slow waves and sometimes spike‐waves | Normal background, generalized polyspike, polyspike‐wave and spike‐wave (13), unknown (9) | Normal |

| Brain MRI | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Global symmetrical cerebellar atrophy (13) unknown (9) | Normal |

| Ataxia | No | No | Mild, so far nonprogressive | Balancing difficulties possible | No | Progressive | No |

| Developmental delay | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mild (2), no (20) | Yes |

| Cognitive Decline | Possible memory deficits (MOCA 28/30) | No | No | No | No | Yes (11), possible (2), no (7) | No |

| Dysmorphism | No | Hypertelorism, long palpebral fissures, broad nose, large ears, diastema, small chin | No | No | No | No | Prognathism, protruding ears, short philtrum, fetal pads, epicanthal folds, ptosis |

| Others | Dystonia, scoliosis | Frequent diarrhea and vomiting | Mild muscular hypotonia | Mild muscular hypotonia | Cannot walk yet | Wheelchair‐dependent (11) | Clinodactyly of the fifth finger (1) |

Functional studies demonstrated a complete loss‐of‐function for all three variants with a significant dominant‐negative effect on WT channels for Thr399Met and Ala421Val (Fig. 2A–D). Similar to the previously published variant Arg320His, Ala421Val caused a hyperpolarizing shift of the activation curve when coexpressed with WT, which was not observed for Cys208Tyr (Fig. 2E).13 In contrast to the haploinsufficiency of the truncating variant in the previously described family with ID, the variant Thr399Met, also causing ID alone, showed a pronounced dominant‐negative effect.16 Our current data do thus not reveal a clear correlation between the electrophysiological properties of mutant channels and clinical phenotypes. It is striking, however, that both recurring variants (Arg320His and Ala421Val) cause a different but homogeneous phenotype each, indicating specific effects of the variants themselves, despite their similar biophysical properties. Further functional characterizations in neuronal cells are needed to shed more light on the cellular and network mechanisms underlying the pathological effect of the variants on the nervous system.

KV3.1 is prominently expressed in inhibitory GABAergic interneurons in which these channels enable high‐frequency firing by a rapid membrane repolarization.10 The identified variants thus probably lead to impaired firing of GABAergic interneurons predicting neuronal disinhibition as the underlying disease mechanism. Patients 3 and 5 were both treated with benzodiazepines. Their effect on GABA neurotransmitters, enhancing the inhibitory effect on neurons might have played a critical role in reducing the patients' seizure frequencies. Also Oliver et al described that clonazepam beside valproate was most effective in MEAK patients.14 Another more specific therapeutic strategy might be to directly activate mutant heterotetrameric KV3 channels. The feasibility of such an approach with a compound called RE01 has been recently reported in vitro.20

In conclusion, we provide evidence that de novo variants in KCNC1 cause more diverse phenotypes than described so far, such as nonprogressive myoclonus (or tremor) alone, intellectual disability, or epilepsy with myoclonic, absence and generalized tonic‐clonic seizures with developmental delay.

Author Contributions

J. P. was responsible for the conception and design of the study, collecting and analyzing the data, and drafting the manuscript. J. P., M. K, U. B. S. H., M. G, S. B. W, M. H., M. S, and T. B. H. contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. A. H., K. C., E. H., B. A., D. K., L. K., A. T., L. C. M., T. M. S., E. B. R., H. E., and M. W. contributed to phenotyping, acquisition, and analysis of data. T.B.H. and H.L. were responsible for the conception, design and supervision of the study, and writing of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript for intellectual content.

Conflict of Interest

Nothing to report.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Brain imaging, X‐ray and EEG of patient 1 with a Cys208Tyr variant.

Figure S2. Brain imaging and EEG of patient 4 with a Ala421Val variant.

Figure S3. EEG‐electromyographic (EMG) recording of patient 5 with a Ala421Val variant.

Table S1. Identified rare variants in patients 1, 2, and 3.

Video S1. The supplementary video shows action myoclonus in patient 1 and myoclonus absence seizures in patients 4 and 5.

Acknowledgments

We thank all families and patients for their declaration of consent to the publication. We thank J. Linn (Universitätsklinikum Carl Gustav Carus, Dresden; Department of Neuroradiology) for providing the MRI and X‐ray images. This study was supported by the German Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) through the Juniorverbund in der Systemmedizin “mitOmics” (FKZ 01ZX1405C to TBH) and the network for rare diseases Treat‐ION (FKZ 01GM1907A), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FOR‐2715, grants Le1030/16‐1 and He8155/1‐1), and the intramural fortüne program (#2435‐0‐0).

Park J, Koko M, Hedrich UBS, et al. KCNC1‐related disorders: new de novo variants expand the phenotypic spectrum. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6:1319–1326. 10.1002/acn3.50799

Funding information

This study was supported by the German Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) through the Juniorverbund in der Systemmedizin “mitOmics” (FKZ 01ZX1405C to TBH) and the network for rare diseases Treat‐ION (FKZ 01GM1907A), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FOR‐2715, grants Le1030/16‐1 and He8155/1‐1), and the intramural fortüne program (#, 2435‐0‐0).

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant FOR-2715; University of Tuebingen grant ; Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung grants FKZ 01GM1907A and FKZ 01ZX1405C; intramural fortüne program grants # and 2435-0-0.

Contributor Information

Holger Lerche, Email: holger.lerche@uni-tuebingen.de.

Tobias B. Haack, Email: tobias.haack@med.uni-tuebingen.de

References

- 1. Maulik PK, Mascarenhas MN, Mathers CD, et al. Prevalence of intellectual disability: a meta‐analysis of population‐based studies. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:419–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ortega‐Moreno L, Giraldez BG, Soto‐Insuga V, et al. Molecular diagnosis of patients with epilepsy and developmental delay using a customized panel of epilepsy genes. PLoS ONE 2017;12:e0188978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waaler PE, Blom BH, Skeidsvoll H, Mykletun A. Prevalence, classification, and severity of epilepsy in children in western Norway. Epilepsia 2000;41:802–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leonard H, Wen X. The epidemiology of mental retardation: challenges and opportunities in the new millennium. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002;8:117–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Helbig KL, Farwell Hagman KD, Shinde DN, et al. Diagnostic exome sequencing provides a molecular diagnosis for a significant proportion of patients with epilepsy. Genet Med. 2016;18:898–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heyne HO, Singh T, Stamberger H, et al. De novo variants in neurodevelopmental disorders with epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1048–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rauch A, Wieczorek D, Graf E, et al. Range of genetic mutations associated with severe non‐syndromic sporadic intellectual disability: an exome sequencing study. Lancet 2012;380:1674–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Figueroa KP, Waters MF, Garibyan V, et al. Frequency of KCNC3 DNA variants as causes of spinocerebellar ataxia 13 (SCA13). PLoS ONE 2011;6:e17811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duarri A, Nibbeling EA, Fokkens MR, et al. Functional analysis helps to define KCNC3 mutational spectrum in Dutch ataxia cases. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0116599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rudy B, McBain CJ. Kv3 channels: voltage‐gated K+ channels designed for high‐frequency repetitive firing. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:517–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Song P, Yang Y, Barnes‐Davies M, et al. Acoustic environment determines phosphorylation state of the Kv3.1 potassium channel in auditory neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1335–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Franceschetti S, Michelucci R, Canafoglia L, et al. Progressive myoclonic epilepsies: definitive and still undetermined causes. Neurology 2014;82:405–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muona M, Berkovic SF, Dibbens LM, et al. A recurrent de novo mutation in KCNC1 causes progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2015;47:39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oliver KL, Franceschetti S, Milligan CJ, et al. Myoclonus epilepsy and ataxia due to KCNC1 mutation: Analysis of 20 cases and K(+) channel properties. Ann Neurol. 2017;81:677–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim H, Lee S, Choi M, et al. Familial cases of progressive myoclonic epilepsy caused by maternal somatic mosaicism of a recurrent KCNC1 p.Arg320His mutation. Brain Dev. 2018;40:429–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Poirier K, Viot G, Lombardi L, et al. Loss of function of KCNC1 is associated with intellectual disability without seizures. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:560–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fritzen D, Kuechler A, Grimmel M, et al. De novo FBXO11 mutations are associated with intellectual disability and behavioural anomalies. Hum Genet. 2018;137:401–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hayflick SJ, Kruer MC, Gregory A, et al. beta‐Propeller protein‐associated neurodegeneration: a new X‐linked dominant disorder with brain iron accumulation. Brain 2013;136(Pt 6):1708–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, et al. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1062–D7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Munch AS, Saljic A, Boddum K, et al. Pharmacological rescue of mutated Kv3.1 ion‐channel linked to progressive myoclonus epilepsies. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;833:255–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aggarwal SK, MacKinnon R. Contribution of the S4 segment to gating charge in the Shaker K+ channel. Neuron 1996;16:1169–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Brain imaging, X‐ray and EEG of patient 1 with a Cys208Tyr variant.

Figure S2. Brain imaging and EEG of patient 4 with a Ala421Val variant.

Figure S3. EEG‐electromyographic (EMG) recording of patient 5 with a Ala421Val variant.

Table S1. Identified rare variants in patients 1, 2, and 3.

Video S1. The supplementary video shows action myoclonus in patient 1 and myoclonus absence seizures in patients 4 and 5.