Abstract

Objective

The Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Flare Group was established to develop a reliable way to identify and measure RA flares in randomized controlled trials (RCT). Here, we summarized the development and field testing of the RA Flare Questionnaire (RA-FQ), and the voting results at OMERACT 2016.

Methods

Classic and modern psychometric methods were used to assess reliability, validity, sensitivity, factor structure, scoring, and thresholds. Interviews with patients and clinicians also assessed content validity, utility, and meaningfulness of RA-FQ scores.

Results

People with RA in observational trials in Canada (n = 896) and France (n = 138), and an RCT in the Netherlands (n = 178) completed 5 items (11-point numerical rating scale) representing RA Flare core domains. There was moderate to high evidence of reliability, content and construct validity, and responsiveness. Factor analysis supported unidimensionality. Rasch analysis showed acceptable fit to the Rasch model, with items and people covering a broad measurement continuum and evidence of appropriate targeting of items to people, ordered thresholds, minimal differential item functioning by language, sex, or age. A summative score across items is defensible, yielding an interval score (0–50) where higher scores reflect worsening flare. The RA-FQ received endorsement from 88% of attendees that it passed the OMERACT Filter 2.0 “Eyeball Test” for instrument selection.

Conclusion

The RA-FQ has been developed to identify and measure RA flares. Its review through OMERACT Filter 2.0 shows evidence of reliability, content and construct validity, and responsiveness. These properties merit its further validation as an outcome for clinical trials.

Keywords: DISEASE EXACERBATION, OMERACT, RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS, PATIENT-REPORTED OUTCOME

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory condition characterized by pain, fatigue, stiffness, and disability1. Episodes of clinically important worsening (disease flares) are common, with up to 57% of patients reporting a flare at or between visits2,3,4. Growing evidence indicates that flares contribute substantially to patient burden, poorer health-related quality of life, disability, radiographic damage, and healthcare use and costs5,6,7,8,9.

While newer therapeutics have revolutionized RA management, there is growing interest in understanding optimal approaches to taper or withdraw treatment once sustained remission is achieved. Although flares are an important endpoint in these trials, they have proven challenging to reliably identify and measure.

To date, investigators have used different flare definitions8,10,11,12, including patient or physician assessments, worsening of American College of Rheumatology core set components, or Disease Activity Score13, with little attempt to measure flare severity. Lack of consensus on flare definition has made it challenging to compare studies or pool results.

The Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) RA Flare Group is a diverse group of international researchers, clinicians, patient research partners (PRP), and others working to create a new tool to identify and measure significant RA flares14,15 from the patient perspective. In this paper we present validation results from testing of the RA Flare Questionnaire (RA-FQ) in several thousand people with RA in 3 countries. At our OMERACT 2016 workshop, this foundational work developing the measure was summarized and results of field testing were reviewed, using the first step of the OMERACT Filter Instrument Selection Algorithm (OFISA or “Eyeball Test”15a) as a guide.

We sought participant endorsement that the RA-FQ adhered to OMERACT’s recommended process when reviewing outcome instruments2,16.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Summary of Foundational Work: Developing an Instrument

Definition of RA flare

Our steering committee (COB, EC, RA, SJB, VPB, RC, DEF, SH, AL, LM, TGW, RC) and a larger working group defined the concept of interest: RA flare. The definition was endorsed at OMERACT 9 in 2008 and included worsening of essential symptoms and effects of sufficient intensity and duration to be actionable (e.g., indicate a need for treatment change)6,17,18. The context of use is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Construct of interest and context of use for RA Flare Questionnaire.

| Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | People with RA who have reached an appropriate target of therapy (e.g., low disease activity or remission) |

| Intervention | Treatment tapering or withdrawal |

| Comparison | Tapering/withdrawal versus continuing treatment; different strategies of tapering |

| Outcome | Patients experiencing significant increases in core flare symptoms (pain, fatigue, stiffness) and effects (physical function, participation) for at least 7 days so as to indicate the need for consideration of retreatment |

| Time | May vary by trial depending on level of symptoms at start, anticipated pharmacodynamics of drugs, and other factors |

| Setting | Clinical trial |

RA: rheumatoid arthritis.

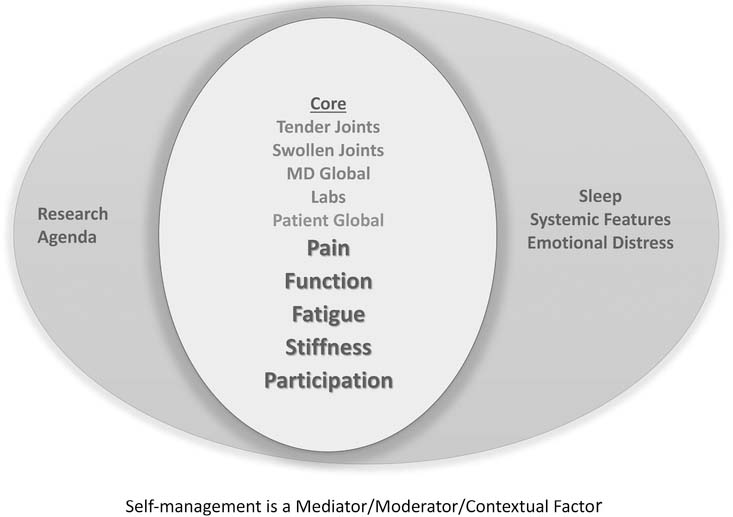

Creating the measurement framework

To develop a measurement framework, we first asked 14 focus groups of patients with RA in 5 countries2 about relevant domains. Candidate domains were prioritized in modified Delphi sessions with 125 patients from 10 countries and 108 clinicians from 23 countries to finalize the RA Flare Core Domain Set19. Domains included the RA core set plus 3 features — fatigue, stiffness, and participation; self-management was recognized as a contextual factor19 (Figure 1). The RA Flare Core Domain Set was ratified at OMERACT 11 in 2012; as well there was overwhelming participant agreement that the patient engagement process was sufficient (91%) and appropriate (85%)16.

Figure 1.

Rheumatoid Arthritis Flare Questionnaire conceptual model. From Bykerk, et al. J Rheumatol 2014;41:799–809; with permission.

In our initial review of existing instruments in 2010, we concluded that neither the Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID-3)20 nor the Rheumatoid Arthritis Impact of Disease (RAID)21 adequately covered all patient-reported flare (PRF) domains (fatigue, stiffness, and participation are not included in RAPID-3, and participation and stiffness are not in RAID.) Thus we identified a need to develop a new instrument that covered all relevant domains.

Creating the measure

Based on our measurement model, we created a prototype self-administered questionnaire of the patient-reported domains of the RA Flare Core Domain Set [i.e., Preliminary Flare Questionnaire (PFQ)]. Respondents were also asked to self-identify if they were in a flare (yes/no), and if yes, to indicate its duration (days) and rate severity (0—10)1. The PFQ was translated into 17 languages, with 23 linguistic and country-specific versions using a rigorous, forward/backward translation process with bilingual content experts (rheumatologists) and cognitive debriefing with 5 native-speaking patients in each country for each translation (Supplementary Table 1, available with the online version of this article)22,23. During the final testing phase, RA clinicians (6 rheumatologists in Baltimore and New York, and others affiliated with OMERACT), 9 patients at an academic medical center in Baltimore, and 10 OMERACT PRP confirmed that the instrument was understandable and clear, with appropriate response choices (Supplementary Table 2, available with the online version of this article).

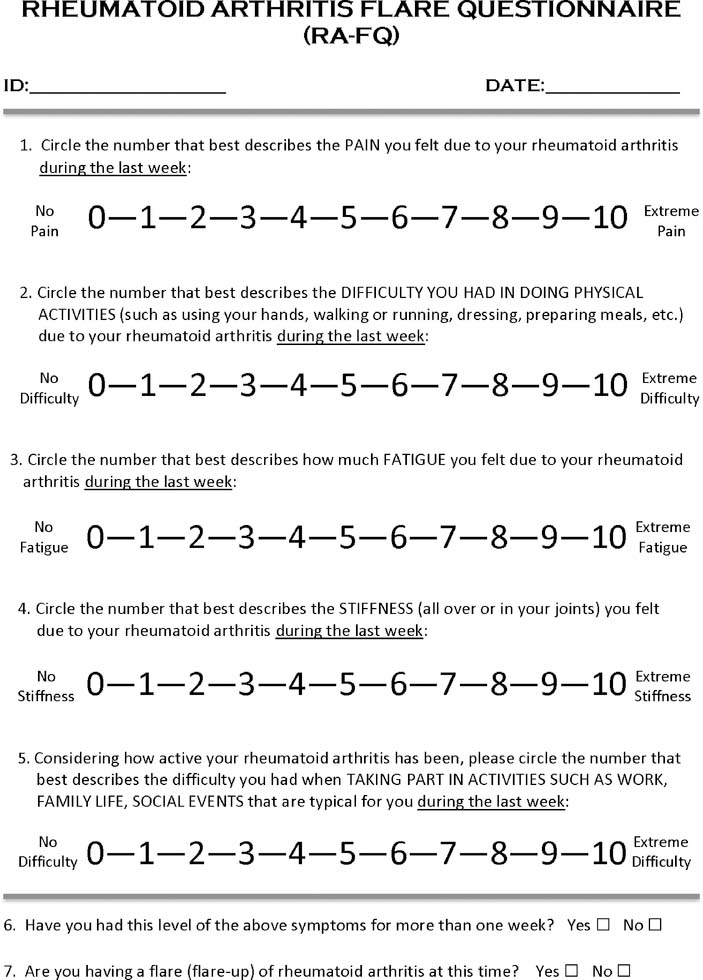

RA-FQ

The RA-FQ contains 5 items to rate pain, physical function, stiffness, fatigue, and participation over the past week using 11-point numeric rating scales (0 = none to 10 = severe; score range 0–50; Figure 2). The RA-FQ will be freely available through OMERACT, with descriptions of psychometric properties, scoring, and interpretation.

Figure 2.

Rheumatoid Arthritis Flare Questionnaire. The RA-FQ score is calculated as the sum of responses for items 1–5 (maximum 50).

Local ethics committees at individual institutions or sites approved all studies.

RESULTS

Does the RA-FQ Pass the Eyeball Test?

We summarized results of 5 years of field testing. Initial validation used data from a Canadian early RA observational study (CATCH; n = 849) and relied on classical test theory (CTT) methods1. Additional validation included factor and Rasch analysis on data from 2 RA observational studies [Canada, CATCH, n = 8961; France, Strategy of Treatment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (STPR), n = 13824], and a randomized controlled trial [RCT; the Netherlands, Dose Reduction Strategy of Subcutaneous TNF Inhibitors in Rheumatoid Arthritis (DRESS), n = 17825; for study descriptions see Supplementary Table 3, available with the online version of this article].

1. Is there a good match with the domain(s)?

Face and content validity

The foundational work was based on a reflective measurement model and grounded in qualitative studies with patients, thus ensuring a good match with patient-reported domains in the RA Flare Core Domain Set. Debriefing of the questionnaire throughout the process provided further evidence of match by people with RA. When combined with the field testing results described below, we concluded that this further supported the face and content validity of the RA-FQ.

2. Is it feasible?

Several thousand patients in RCT and observational trials in several countries have completed the RA-FQ paper forms and using electronic data collection systems (e.g., REDCap, US National Institutes of Health Assessment Center26), with additional data collection ongoing. Among 46 patients with RA at 2 academic arthritis centers (Baltimore and New York), mean (SD) completion time was 1.5 (1.1) min. Patients with RA and OMERACT PRP agreed that the format was appropriate and easy to complete (Supplementary Table 2, available with the online version of this article). Availability in multiple languages increases feasibility of use in multinational studies. We concluded there was sufficient evidence to support feasibility in clinical and observational trials.

3. Do the numeric scores make sense?

To examine construct validity, we developed multiple ways to potentially identify RA flares in the datasets. Then, CTT and Rasch approaches were used to evaluate the factor structure to guide scoring. Next, RA-FQ scores were compared with other indicators of RA disease activity.

Construct validity: identifying flares

In the absence of a gold standard for flare, construct validation offers evidence that an instrument is measuring what it purports to measure27. We hypothesized that PRF (answers “yes” to question: “Are you in a flare?”) would be moderately to highly correlated with MD-identified flare (MDF), and Disease Activity Score at 28 joints flare criteria (DAS28F; DAS28 increase > 1.2 or > 0.6 if DAS28 at previous visit was ≥ 3.213). We have previously shown that in patients who were previously in remission, agreement was high (κ ≥ 0.73) for flare status among PRF, MDF, and DAS28F; in low disease activity (LDA), agreement was moderate to strong between PRF and MDF, and PRF and DAS28F (κ = 0.44–0.63)1.

To increase confidence that the PRF represented clinically important worsening that was consistent with our definition of flare17,28 and that would be actionable in a clinical trial, we added additional criteria that would take into account intensity (4/10 on severity scale) and duration (> 7 days). This more stringent definition of PRF (hereafter referred to as PRF-SD) was based on discussions among the steering group and members of the larger RA flare working group. Receiver−operation characteristic (ROC) curves were used to analyze the performance of the severity and duration cutpoints among patients where both the patient and MD agreed that the patient was in flare, supporting these cutpoints as discrimination thresholds consistent with clinically important worsening (Supplementary Figure 1, available with the online version of this article). Among CATCH patients, we also identified cases in which the patient and MD both agreed that the patient was in a flare (P-MDF). The 5 definitions of flare were used for subsequent analyses as described below.

Validity of flare domain scores

We have previously shown that PFQ domain scores were moderately to highly (r > 0.7) correlated with existing scales measuring the same or related domains1. Domain scores were also significantly higher in those who were in a flare versus those who were not in a flare.

Validity of RA-FQ

To establish an appropriate scoring system, we used factor analysis to examine structural validity. The 5 items represented a single factor (81% of variance explained) with each item loading ≥ 0.84 (eigenvalue 4.064), supporting use of a summative score of the 5 domains (range 0 = no flare to 50 = extreme flare) to adequately represent RA flares. In CATCH patients, we compared RA-FQ mean scores and other indicators of disease activity in flaring and non-flaring patients. Flaring patients had significantly higher RA-FQ scores and disease activity indicators, except for acute-phase reactants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean (SD) scores of RA-FQ and other RA disease activity indicators by flare* status in the Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort.

| Variables | Flare*, n = 51 | No Flare*, n = 571 | Mean Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RA-FQ | 29.0 (10.2) | 9.4 (10.0) | 19.6 (16.7–22.6) |

| Tender joint count | 5.3 (5.8) | 1.6 (3.3) | 3.7 (2.0–5.4) |

| Swollen joint count | 3.0 (5.2) | 1.1 (2.4) | 1.9 (0.4–3.4) |

| MD global | 2.5 (2.4) | 0.9 (1.6) | 1.6 (0.9–2.3) |

| Patient global | 5.2 (1.5) | 1.7 (1.8) | 3.4 (2.9–4.0) |

| Pain, 10 mm VAS | 6.2 (2.1) | 2.0 (2.2) | 4.2 (3.6–4.9) |

| HAQ, 0–3 | 0.8 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) |

| ESR | 19.8 (19.5) | 15.9 (16.0) | 4.0 (−1.5 to 9.4) |

| CRP | 8.0 (12.9) | 5.2 (8.9) | 2.8 (−1.2 to 6.8) |

| DAS28 | 4.2 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.1–2.2) |

Both patient and MD classified the patient as being in a flare.

RA-FQ: Rheumatoid Arthritis Flare Questionnaire; VAS: visual analog scale; HAQ: Health Assessment Questionnaire; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein; DAS28: Disease Activity Score in 28 joints.

Rasch analysis

Rasch analysis was used to further analyze measurement properties and scoring of the RA-FQ29 in the combined dataset. We examined response thresholds, how well the items worked together, targeted the population of interest, and reflected a unidimensional continuum using RUMM2030 (rating scale model). Reliability, local dependence (items in a scale should not be related to each other or redundant), and differential item functioning (DIF; item bias) were also examined. Items and people covered a broad continuum (> ± 3 logits), covering 99% of targeted range. Results suggested excellent fit with the Rasch model, high reliability (e.g., Person Separation Index > 0.9), 10 well-ordered thresholds for each item, minimal redundancy among items, and minimal DIF by age, sex, or country/language. Rasch results affirm that responses can be added across items to yield a total score (range 0–50) on an interval scale where higher values reflect worsening flare. (Rasch data will be described in greater detail in a separate publication.)

We concluded that results of psychometric methods offered evidence supporting the construct validity of the RA-FQ.

4. Can the RA-FQ evaluate change?

Test-retest reliability

Test scores obtained at 2 timepoints in stable patients should not change. RA-FQ obtained 48–72 h apart (a time during which no change would be anticipated) in 93 patients with RA at 2 academic centers suggested high reliability [r = 0.94; ICC (2, 1) = 0.93, 95% CI 0.90–0.95].

Responsiveness

From CATCH, DRESS, and STPR studies, we selected patients who started in remission/LDA at baseline (DAS28 < 3.2) because this would represent typical patients entering tapering/withdrawal trials. Compared with those who did not flare at the second visit, flaring patients had significantly higher RA-FQ scores using 3 flare definitions (PRF, PRF-SD, DAS28F), with moderate to large effect sizes evident (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rheumatoid Arthritis Flare Questionnaire scores by flare status at 2 consecutive visits using 3 definitions of flare.

| Flare Definition | Flare | No Flare | Mean V2 Difference (95% CI) | Effect Size† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | V2 | V1 | V2 | |||

| CATCH (observational) | ||||||

| PRF* | 13.4 | 22.5 | 9.8 | 8.5 | 14.0 (11.4–16.5) | 1.39 |

| PRF + severity + duration** | 16.6 | 29.0 | 9.9 | 9.4 | 19.6 (16.7–22.6) | 1.95 |

| DAS28 flare criteria*** | 11.8 | 26.8 | 10.0 | 9.3 | 17.5 (13.6–21.5) | 1.73 |

| DRESS (RCT) | ||||||

| PRF* | 17.4 | 22.4 | 11.6 | 12.2 | 10.2 (5.6–14.8) | 1.10 |

| PRF + severity + duration** | 16.7 | 31.3 | 12.2 | 12.9 | 18.3 (8.9–27.8) | 1.10 |

| DAS28 flare criteria*** | 18.7 | 24.6 | 11.6 | 12.2 | 12.4 (7.7–17.2) | 1.37 |

| STPR (observational) | ||||||

| PRF* | 17.5 | 22.7 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 9.6 (3.6–15.6) | 1.10 |

| PRF + severity + duration** | 17.1 | 25.3 | 13.3 | 13.7 | 11.5 (2.3–20.8) | 1.30 |

| DAS28 flare criteria*** | 16.5 | 20.5 | 13.9 | 13.2 | 7.3 (1.4–13.2) | 0.82 |

Cohen d statistic.

Patients answered “yes” to the question “Are you having a flare at this time?”

PRF AND patient-rated severity > 4/10 AND reported duration > 7 days.

Required increase in DAS28 > 1.2 or > 0.6 if DAS at previous visit was ≥ 3.2.

V1: visit 1; V2: visit 2; CATCH: Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort; PRF: patient-reported flare; DAS28: Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; DRESS: Dose Reduction Strategy of Subcutaneous TNF Inhibitors in Rheumatoid Arthritis; RCT: randomized controlled trial; STPR: Strategy of Treatment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis.

We concluded that initial reliability and responsiveness data suggested that RA-FQ is responsive to change. However, results should be considered preliminary until the publication of additional responsiveness data from clinical trials. (These data are currently being collected with results forthcoming.)

5. Can the RA-FQ define thresholds of meaning for individual patients?

Using ROC curves, we have begun examining thresholds in RA-FQ scores to identify flare; because identification of flare may trigger retreatment, specificity (i.e., correctly identifying those not in a flare) was prioritized over sensitivity. Because a cutpoint to identify flares may differ somewhat depending on the desired outcome, population, and setting, we analyzed thresholds using multiple definitions of flare (PRF, PRF-SD, DAS28F, P-MDF). We also investigated cutpoints in relation to prespecified changes in patient global, MD global, DAS, and Clinical Disease Activity Index. Work is ongoing to establish relevant cutpoints to identify flare in various settings and RA subsets.

Results of field testing data offer evidence of feasibility, construct and content validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the RA-FQ. Strengths of our validation approach include the use of both classical and modern psychometric methods, testing done with patients similar to those with whom the measure is likely to be used, and administration across different samples of international patients with RA. There is evidence from the Rasch analysis that a simple summative score is meaningful and reliable. Limitations include the absence of a gold standard to identify flares and limited evidence that identifying and addressing flares improves longterm outcomes. Table 41,2,6,14,18,19 summarizes our validation activities prior to OMERACT 2016, including the stages at which different steps have been presented and endorsed.

Table 4.

History of endorsement by OMERACT participants for OMERACT Filter 2.1 Instrument Selection Algorithm steps for the RA Flare Questionnaire.

| Step | Evidence | OMERACT Endorsement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | ||

| 1. Is there a good match with domain? | Identifying RA Flare Core Domains: Focus groups6/Delphi exercises19 | * | ||

| Face and content validity1, 2, 14, 18 | * | * | * | |

| 2. Is it feasible to use? | Implementation in clinical trials and observational studies from perspectives of patients, clinicians, other stakeholders1,2; translation into multiple languages | * | * | |

| 3. Do the numbers make sense? | Reliability, concurrent, discriminative, convergent, consequential validity1,2; factor analysis and Rasch analysis | * | Passed Eyeball Test | |

| 4. Can it evaluate change in patients? | Test-retest reliability, responsiveness1 | Passed Eyeball Test | ||

| 5. Have relevant thresholds been defined? | Preliminary results from ROC curves; work is ongoing to establish thresholds in different populations and settings | Passed Eyeball Test | ||

OMERACT: Outcome Measures in Rheumatology; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; ROC: receiver-operation characteristic.

Small group discussions

Small group discussions during the workshop were conducted to allow more in-depth review of data and to obtain feedback from attendees. Report-backs were largely supportive of the methods used and interpretation of data, and recommendations were offered regarding formatting, presentation of results, and additional analyses to consider, to enhance use in different settings and with subsets of patients with RA.

Voting results

Initial voting at the end of the workshop focused on whether the presented data were sufficient to pass each Eyeball Test question. Consensus [defined as “Green” (no concerns; strong recommendation) PLUS “Amber” (some concerns; conditional recommendation) votes being ≥ 70%] was obtained as follows: (1) match with domain (93%), (2) feasibility (98%), (3) does score make sense (94%), (4) able to measure change (91%), and (5) thresholds of meaning (87%).

Voting results stimulated discussions between the RA flare steering committee and other participants during the remaining days of OMERACT that helped enhance the understanding of the relative strengths and weaknesses of our approach and the interpretation of the results. At the final vote, 88% of participants (70% no concerns, 18% some concerns) agreed that the RA-FQ passed the OFISA Eyeball Test.

DISCUSSION

OMERACT 2016 participants agreed that the RA-FQ fulfilled initial OFISA screening, supporting its potential as a valid and acceptable measure of RA flare. In our OMERACT 2016 plenary workshop, we showed how, by working iteratively with PRP, clinicians, and others and using a mixed-methods approach, we developed a new outcome measure in rheumatology in accordance with OMERACT Filter 2.030. The OFISA (Eyeball Test) was developed to help researchers initially screen the literature for valid and acceptable outcome measures to potentially include in Core Outcome Measurement Sets. In the plenary, we demonstrated how OFISA could also be used to organize the results of field testing activities when developing a new instrument.

During the plenary, we summarized results of psychometric testing of the RA-FQ from data obtained over 6 years with > 2000 patients across 3 countries. Factor analysis supported unidimensionality of the set of items, and Rasch analysis demonstrated that response options were appropriate, items worked well together, and that the measure was well targeted to patients with RA across the full measurement continuum. The RA-FQ performed similarly in different subgroups (age, sex) and across 3 countries and languages supporting measurement invariance. The RA-FQ is easily scored and readily interpreted by patients and physicians. All these results increase confidence that the RA-FQ can reliably and precisely identify and measure RA flares, although it remains unclear whether addressing flares promptly will improve longterm RA outcomes. Voting results supported adequate initial evidence of feasibility, reliability, validity, and responsiveness.

The RA Flare Group is acquiring additional data from several large RCT and observational studies to establish appropriate thresholds to identify RA flare for different settings and uses.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful for the contribution of investigators and patients involved in the CATCH Study, the DRESS Study, and the STPR Study.

SJB, COB, VPB, ALL, and AL have received support from a Methods Award (SC14–1402-10818) and/or a Eugene Washington Dissemination Award (EAIN-1988) from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). COB and work presented in this grant have been supported by P30-AR053503, Rheumatic Diseases Research Core Center, Human Subjects Research Core, funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS). Additional funding came from the Camille Julia Morgan Arthritis Research and Education Fund. VPB is supported by the Cedar Hill Foundation and by NIH grant 1UH2AR067691. RC and the Parker Institute are supported by grants from the Oak Foundation. SPB received support to attend OMERACT 2016 as the RA Flare Group fellow. UCB Inc. supported translation of the preliminary flare questionnaire into various linguistic and country-specific versions. UCB and Pfizer have incorporated the preliminary flare questionnaire into clinical trials for field testing. Pfizer (Germany) has provided unrestricted grants to support the efforts of the OMERACT Flare Working Group. All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH or NIAMS, or PCORI, its board of governors or methodology committee.

Footnotes

ONLINE SUPPLEMENT

Supplementary material accompanies the online version of this article.

Contributor Information

Susan J. Bartlett, McGill University, and Johns Hopkins University

Skye P. Barbic, University of British Columbia

Vivian P. Bykerk, Hospital for Special Surgery

Ernest H. Choy, Cardiff University

Rieke Alten, Schlosspark-Klinik University Medicine.

Robin Christensen, Parker Institute, Copenhagen University.

Alfons den Broeder, Sint Maartenskliniek.

Bruno Fautrel, Pierre et Marie Curie University.

Daniel E. Furst, University of California

Francis Guillemin, University of Lorraine.

Sarah Hewlett, University of the West of England.

Amye L. Leong, Healthy Motivation

Anne Lyddiatt, Patient Research Partner.

Lyn March, University of Sydney.

Pamela Montie, Patient Research Partner.

Christoph Pohl, Schlosspark-Klinik University Medicine.

Marieke Scholte Voshaar, VU.

Thasia G. Woodworth, University of California

Clifton O. Bingham, III, Johns Hopkins University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bykerk VP, Bingham CO, Choy EH, Lin D, Alten R, Christensen R, et al. Identifying flares in rheumatoid arthritis: reliability and construct validation of the OMERACT RA Flare Core Domain Set. RMD Open 2016;2:e000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartlett SJ, Bykerk VP, Cooksey R, Choy EH, Alten R, Christensen R, et al. Feasibility and domain validation of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Flare Core Domain Set: report of the OMERACT 2014 RA Flare Group Plenary. J Rheumatol 2015;42:2185–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bykerk VP, Shadick N, Frits M, Bingham CO 3rd, Jeffery I, Iannaccone C, et al. Flares in rheumatoid arthritis: frequency and management. A report from the BRASS registry. J Rheumatol 2014;41:227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lie E, Woodworth TG, Christensen R, Kvien TK, Bykerk V, Furst DE, et al. Validation of OMERACT preliminary rheumatoid arthritis flare domains in the NOR-DMARD study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1781–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Maas A, den Broeder AA. Measuring flares in rheumatoid arthritis. (Why) do we need validated criteria? J Rheumatol 2014;41:189–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewlett S, Sanderson T, May J, Alten R, Bingham CO 3rd, Cross M, et al. ‘I’m hurting, I want to kill myself’: rheumatoid arthritis flare is more than a high joint count—an international patient perspective on flare where medical help is sought. Rheumatology 2012;51:69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myasoedova E, Chandran A, Ilhan B, Major BT, Michet CJ, Matteson EL, et al. The role of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) flare and cumulative burden of RA severity in the risk of cardiovascular disease. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:560–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuijper TM, Lamers-Karnebeek FB, Jacobs JW, Hazes JM, Luime JJ. Flare rate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in low disease activity or remission when tapering or stopping synthetic or biologic DMARD: a systematic review. J Rheumatol 2015;42:2012–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markusse IM, Dirven L, Gerards AH, van Groenendael JH, Ronday HK, Kerstens PJ, et al. Disease flares in rheumatoid arthritis are associated with joint damage progression and disability: 10-year results from the BeSt study. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fautrel B, den Broeder AA. De-intensifying treatment in established rheumatoid arthritis (RA): Why, how, when and in whom can DMARDs be tapered? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2015; 29:550–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida K, Sung YK, Kavanaugh A, Bae SC, Weinblatt ME, Kishimoto M, et al. Biologic discontinuation studies: a systematic review of methods. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:595–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka Y, Hirata S, Saleem B, Emery P. Discontinuation of biologics in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2013;31 Suppl 78:S22–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Maas A, Lie E, Christensen R, Choy E, de Man YA, van Riel P, et al. Construct and criterion validity of several proposed DAS28-based rheumatoid arthritis flare criteria: an OMERACT cohort validation study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1800–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bingham CO 3rd, Alten R, Bartlett SJ, Bykerk VP, Brooks PM, Choy E, et al. ; OMERACT RA Flare Definition Working Group. Identifying preliminary domains to detect and measure rheumatoid arthritis flares: report of the OMERACT 10 RA Flare Workshop. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1751–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bingham III, Pohl C, Alten R, Christensen R, Choy E, Hewlett S, et al. “Flare” and disease worsening in rheumatoid arthritis: time for a definition. Int J Adv Rheumatol 2009;7:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Boers M, Kirwan JR, Tugwell P, Beaton D, Bingham III, Conaghan P, et al. The OMERACT Handbook. Ottawa, CA: OMERACT; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bykerk VP, Lie E, Bartlett SJ, Alten R, Boonen A, Christensen R, et al. Establishing a core domain set to measure rheumatoid arthritis flares: report of the OMERACT 11 RA flare Workshop. J Rheumatol 2014;41:799–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bingham CO 3rd, Pohl C, Woodworth TG, Hewlett SE, May JE, Rahman MU, et al. Developing a standardized definition for disease “flare” in rheumatoid arthritis (OMERACT 9 Special Interest Group). J Rheumatol 2009;36:2335–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alten R, Pohl C, Choy EH, Christensen R, Furst DE, Hewlett SE, et al. ; OMERACT RA Flare Definition Working Group. Developing a construct to evaluate flares in rheumatoid arthritis: a conceptual report of the OMERACT RA Flare Definition Working Group. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1745–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartlett SJ, Hewlett S, Bingham CO 3rd, Woodworth TG, Alten R, Pohl C, et al. ; OMERACT RA Flare Working Group. Identifying core domains to assess flare in rheumatoid arthritis: an OMERACT international patient and provider combined Delphi consensus. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1855–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pincus T Is a self-report RAPID3 score a reasonable alternative to a DAS28 in usual clinical care? J Clin Rheumatol 2009;15:215–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gossec L, Paternotte S, Aanerud GJ, Balanescu A, Boumpas DT, Carmona L, et al. Finalisation and validation of the rheumatoid arthritis impact of disease score, a patient-derived composite measure of impact of rheumatoid arthritis: a EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:935–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000;25:3186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, et al. ; ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health 2005;8:94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fautrel B, Morel J, Berthelot JM, Constantin A, De Bandt M, Gaudin P, et al. ; STPR Group of the French Society of Rheumatology. Validation of FLARE-RA, a self-administered tool to detect recent or current rheumatoid arthritis flare. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:309–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.den Broeder AA, van Herwaarden N, van der Maas A, van den Hoogen FH, Bijlsma JW, van Vollenhoven RF, et al. Dose REduction strategy of subcutaneous TNF inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: design of a pragmatic randomised non inferiority trial, the DRESS study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gershon RC, Rothrock N, Hanrahan R, Bass M, Cella D. The use of PROMIS and assessment center to deliver patient-reported outcome measures in clinical research. J Appl Meas 2010;11:304–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Vet HC, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL. Measurement in medicine: a practical guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bingham CO 3rd, Ince A, Haraoui B, Keystone EC, Chon Y, Baumgartner S. Effectiveness and safety of etanercept in subjects with RA who have failed infliximab therapy: 16-week, open-label, observational study. Curr Res Med Opin 2009;25:1131–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tennant A, Conaghan PG. The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: what is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper? Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:1358–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boers M, Kirwan JR, Gossec L, Conaghan PG, D’Agostino MA, Bingham CO 3rd, et al. How to choose core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: OMERACT 11 approves filter 2.0. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1025–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.