Abstract

There have been numerous controversies surrounding cosmetic products and increased cancer risk. Such controversies include associations between parabens and breast cancer, hair dyes and hematologic malignancies, and talc powders and ovarian cancer. Despite the prominent media coverage and numerous scientific investigations, the majority of these associations currently lack conclusive evidence. In 2016, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) made publically available all adverse event reports in Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition’s Adverse Event Reporting System (CAERS), which includes complaints related to cosmetic products. We mined CAERS for cancer-related reports attributed to cosmetics. Between 2004 and 2017, cancer-related reports caused by cosmetics represented 41% of all adverse events related to cosmetics. This yielded 4427 individual reports of cancer related to a cosmetic product. Of these reports, the FDA redacted the specific product names in 95% of cancer-related reports under the Freedom of Information Act exemptions, most likely due to ongoing legal proceedings. For redacted reports, ovarian cancer reports dominated (n = 3992, 90%), followed by mesothelioma (n = 92, 2%) and malignant neoplasm unspecified (n = 46, 1%). For nonredacted reports, or those reports whose product names were not withheld (n = 218), 70% were related to ovarian cancer attributed to talc powders, followed by skin cancer (11%) and breast cancer (5%) attributed to topical moisturizers. Currently, CAERS is of limited utility, with the available data having been subjected to significant reporter bias and a lack of supportive information such as demographic data, medical history, or concomitant product use. Although the system has promise for safeguarding public health, the future utility of the database requires broader reporting participation and more complete reporting, paired with parallel investments in regulatory science and improved molecular methods.

Recent Controversies: Carcinogenic Cosmetics and Personal Care Products

There have been numerous controversies surrounding cosmetics and their chemical constituents with carcinogenesis. Examples include associations of parabens and aluminum with breast cancer (1,2–4), talc powder with ovarian cancer (5–10), and, most recently, hair dye with breast cancer (11). These articles have often been covered extensively by the media and have stoked consumer concerns. Several of these initial epidemiological associations have not been reproduced in larger cohort studies, as in the case of talc powder and ovarian cancer (12,13), or follow-up toxicology analyses by other scientists or regulatory agencies (14–17). Given the ubiquitous use of cosmetics, oncologists often face questions from patients concerning the possible etiology of these products in relation to a cancer diagnosis. As one indication, the American Cancer Society publishes numerous “frequently asked questions” surrounding cosmetics and carcinogenesis for the public, suggesting the inherent need for such clarification to the lay public (18).

The Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition’s Adverse Event Reporting System

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) made the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition’s Adverse Event Reporting System (CAERS) publicly available in late 2016 to increase transparency and encourage adverse event reporting from consumers related to cosmetics. A recent update of the database in 2017 includes adverse event reported to the FDA related to cosmetics submitted by consumers and health care providers from January 2004 to March 2017. A previous study of an earlier version of this database identified hair products, skin care products, and tattoos (nonpermanent) as the cosmetic products most often associated with adverse events (19). However, there was no further analysis of specific symptom complaints.

All CAERS reports for cosmetics from 2004 to March 2017 were extracted on May 30, 2017, and examined for duplicates or incomplete entries. Entries were then sorted based on the specific self-reported negative health effects. Products whose effects did not include cancer or cancer-associated search terms were excluded. Search terms included “cancer,” “neoplasm,” “leukemia,” “mass,” “adenoma,” “lesion,” “metaplasia,” “carcinoma,” “malignant,” and “metastatic.” Products associated with cancer were then categorized into one of five broader categories: talc powders, hair products, moisturizers, cleansers, tanning products, or miscellaneous. The miscellaneous category includes nail polish, oral products, deodorants, and makeup products. These were organized by number of total reports and individual cancer types. The majority of cancer-related reports for cosmetic products were “redacted” in the database under the Freedom of Information Act exemptions. These exemptions include records that are being compiled for law enforcement purposes, attorney work-products being used in preparation for litigation, or information that would interfere with pending law enforcement matters (20). These redacted reports were included in overall cancer reports but removed for product class-specific analyses. Available demographic data from reporters were collected. Our goal was to determine whether useful insights could be derived from this national database for cancer epidemiology and cosmetics.

CAERS Reports Associating Cosmetics With Cancer From 2004 to 2017

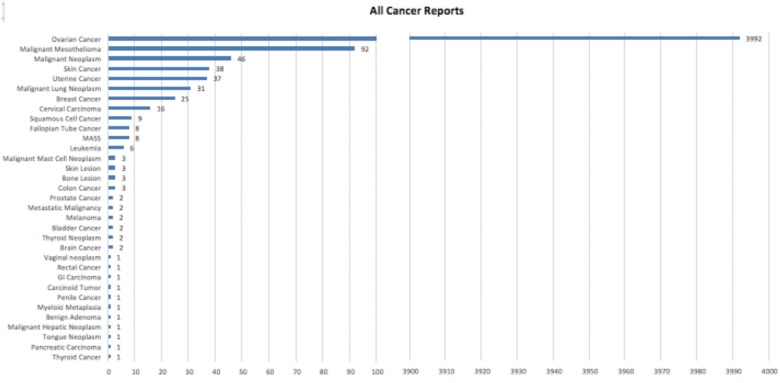

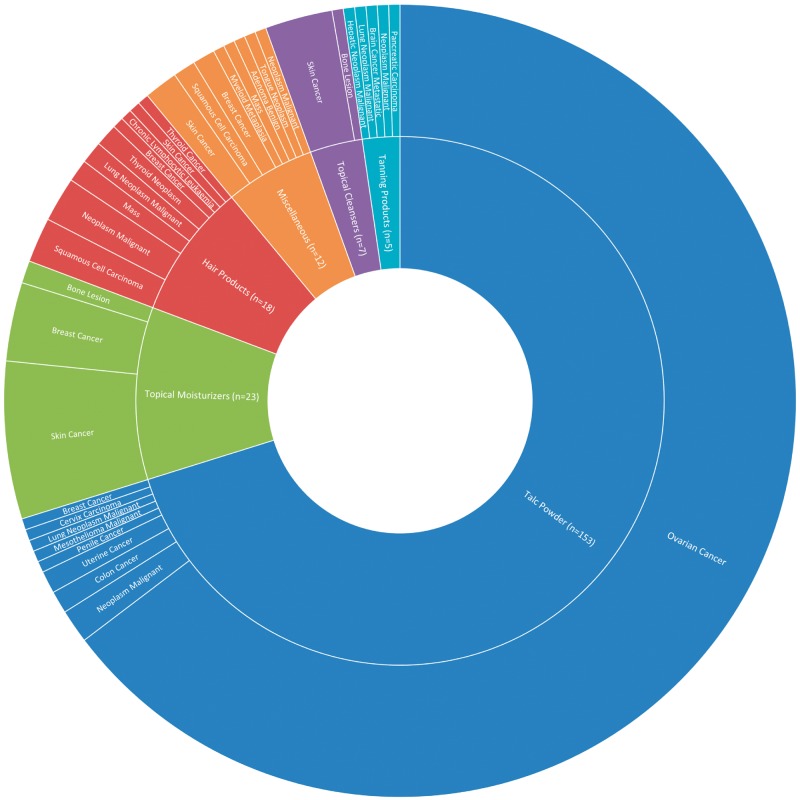

A total of 4427 cancer-related adverse events were reported to the FDA database associated with cosmetics (Figure 1). This represents 41% of all cosmetic adverse events (10 726 total). The majority of cancer reports were associated with products whose names were redacted in CAERS (n = 4210, 95.1% of all cancer reports). Overall, the available demographic data of reporters were limited. The average age of all respondents with any adverse event was 48 years (range < 1–95 years); 84% of respondents were female, 11% were male, and 5% did not indicate sex. Of all cases, including redacted reports, ovarian cancer reports dominated (n = 3992, 90%), followed by mesothelioma (n = 92, 2%) and then malignant neoplasm unspecified (n = 46, 1%). Of the nonredacted reports (n = 218) where product classes were available (Figure 2), talc powders were most associated with a report of cancer, composing 70% of all cancer reports (n = 153). Within the cancers associated with talc powders, ovarian cancer composed the majority, with 141 cases (92%). Only 15 cases reported a specific ovarian cancer subtype (granulosa, serous cystadenocarcinoma, epithelial, and clear cell). The next most commonly reported cancers for talc powder included malignant mesothelioma (2.1%), malignant neoplasm (1.1%), skin cancer (1%), and uterine cancer (0.01%). Topical moisturizers consisted of 10.5% of nonredacted cancer reports. Specifically, moisturizers were attributed by reporters to skin cancer (n = 14, 11%), breast cancer (n = 7, 5%), and bone lesions (n = 2). Hair products were the third most common product class, composing 8.3% of total cancer cases and associated with nine different types of cancer. In total, 33 individual cancers were reported in the CAERS database. Ten of these cancers were associated with only one reported case and 15% of all the reported cancer-associated outcomes were nonspecific. These included reports of “neoplasm malignant,” “mass,” or “metastatic malignancy.”

Figure 1.

Reported cases of cancer from cosmetics in the US Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition’s Adverse Event Reporting System. All reports were sorted into specific cancer types regardless of product type and/or whether product names had been redacted. Overall, we identified 4427 individual reports related to a cancer adverse event related to cosmetics. The majority of cancer reports were those of ovarian cancer (n = 3992), representing 90.2% of all cancer reports. The next most commonly reported cancers were malignant mesothelioma (n = 92), malignant neoplasm (n = 46), skin cancer (n = 38), and uterine cancer (n = 37).

Figure 2.

Sunburst chart indicating product type and associated cancer. Nonredacted cancer reports were divided into five large categories of product types: talc powders, topical moisturizers, hair products, miscellaneous, topical cleansers, and tanning products. These product classes are represented in the inner circle with blue, green, red, orange, purple, and light blue, respectively. The miscellaneous category included oral hygiene products, nail polish, and lip products. The outer circle depicts specific cancer types associated with each product class, with the size of each wedge being proportional to the number of reports. Of the 218 nonredacted cancer reports, 153 were associated with talc powders. The majority of cancer reports associated with talc were of ovarian cancer (n = 144). Other commonly associated classes included topical moisturizers (n = 23), hair products (n = 16), and miscellaneous (n = 12). Redacted reports included the reported adverse event; however, the associated product names were not released. Four thousand two hundred ten reports were associated with redacted product names, composing 95% of reported cancer cases, with the majority representing ovarian cancer reports.

Limitations of the CAERS Database

Reports to the FDA can be done through physical mail, fax, or online with specific forms (21). Respondents must first choose to fill out the form as a consumer or health care professional. Then, each form first asks about the actual reaction (in which reporters can freely type out the adverse reaction in paragraph form), patient information (currently optional to list comorbidities and current medications), product information, and, within the health care professionals form only, concomitant product use. While some association between cancer and cosmetics are observed with these reports, there were several challenges with data extraction and interpretation due to the inherent limitations of the database, as noted previously (19,22). First, the inclusion of nonspecific categories such as “mass” or “neoplasm malignant” makes these reports largely uninterpretable. Lack of further cancer subtyping also limits interpretation as different subtypes can have widely variant pathogenesis. For example, knowledge of the subtype of ovarian cancer (eg, serous, germ cell) is necessary to determine causal relationships. Furthermore, the lack of concomitant medical problems of respondents also severely limits any conclusions drawn for this database. For example, a consumer reporting skin cancer related to a cosmetic may also have had significant tanning bed use. Finally, the duration and frequency of a specific cosmetic and any concomitant cosmetic product use must be included as well. Without a record of these comorbidities, it is impossible to draw conclusions of causality from this database.

Challenges Linking Increased Cancer Risk to Cosmetics and Personal Care Products

Broadly, one of the biggest challenges facing the safety and regulation of cosmetic products is the limitations on the FDA to take action against cosmetic products of potential public health risk. The Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act (FDCA) passed in 1938 allows the FDA to remove harmful food products and regulate which drugs may be sold on the market; however, regulation of cosmetic products is limited to premarket testing of color additives (23). The FDCA does not require companies to report safety information on any other product components and only allows the FDA to recall products that are “adulterated” or “misbranded.” Similarly, the Consumer Product Safety Act excludes cosmetic products. This lack of regulatory power significantly inhibits the ability to assess chemicals prior to their inclusion or develop appropriate metrics for hazardous ingredients.

The assessment of the carcinogenicity of chemicals and chemical mixtures currently relies on a combination of the use of laboratory studies using animal models and human epidemiological studies (24). Often, carcinogenicity is first established or highly suspected when positive laboratory results are obtained in one or more animal species (25). However, species-specific mechanisms that are not applicable in humans must be considered, and experimental parameters including the route of exposure, species, strain, sex, age, and duration of exposure must be taken into account when attempting to extrapolate findings from animals to humans (24). For instance, several studies have shown endocrine disruption in rats exposed to parabens (26,27). However, while endocrine disruption is thought to be the mechanism behind parabens that cause breast cancer, several studies in humans have found no association (15).

In epidemiological studies, biomarkers have increasingly been employed in human studies to investigate links between exposures to exogenous chemicals and cancer risk (28). Because biomarkers capture molecular signatures of exposure, early effects, and susceptibility across the entire exposure-disease continuum, they are critical for assessing causality in cancer research (29). Taken together with data obtained from laboratory animal studies, results from molecular epidemiology can help to build multilayer evidence for causal claims.

However, given the vast numbers of untested chemicals that are currently in commerce in the United States, it is clearly not feasible to conduct costly and time-consuming laboratory animal studies and/or epidemiology studies on all chemicals (30). As a result, cost-effective and high-throughput screening methods are critically needed that can help pinpoint suspected carcinogens for subsequent follow-up evaluation. Major federal research initiatives that are currently working to address this need include the US Environmental Protection Agency’s ToxCast Program (31), the National Toxicology Program’s High Throughput Screening Initiative (32), and the interagency Tox21 Initiatives (33), which are focused on developing rapid screening methods for testing large numbers of chemicals for toxicity. Carcinogenicity testing has also recently begun to incorporate more efficient in vivo and in vitro mechanism-based screening that focuses on early biological indicators of toxicity, as opposed to targeting cancer end points (34). This understanding could ultimately increase the capacity of high-throughput carcinogenicity testing to help identify candidate carcinogens for further evaluation. Fundamentally, it is challenging to prove causality for an individual chemical applied topically over many years with a specific cancer within the context of exposures to hundreds of other confounding chemicals and the complex multifactorial etiology of many cancers.

Media Attention and Cosmetics

Recently, talc baby powder has received substantial media attention. Within the CAERS database, most ovarian cancer reports happened after 2015, coinciding with a peak of hundreds of class-action lawsuits filed against Johnson and Johnson for their talcum products (35). This peak was sustained in 2016, when Johnson and Johnson paid hundreds of millions in damages and settlements related to talc baby powders. Such outside influences likely prompt recall bias and obscure the causal relationships observed within this database. The media itself is also subject to reporter bias in regard to scientific studies relating to cosmetics and carcinogenesis. Highlighting positive associations makes for better headlines. A survey of 937 members of the Society of Toxicology showed that 80% of respondents believed that popular media overstate products risks (36).

Cancer Associations Identified in CAERS: Support for or Lack of Collateral Biomedical Evidence

The concern for talc products initially arose because of its chemical similarity to asbestos, a chemical shown to cause ovarian cancer in occupational settings (37–40). Hypotheses on the mechanism behind talc powder’s carcinogenicity include the impact of estrogen and/or prolactin on macrophages and the inflammatory response to talc (41). Macrophages and monocytes have previously been shown to play a role in scavenging talc (42). Experiments in pregnant mice have shown estrogen-mediated impaired macrophage response to titanium dioxide exposure, a molecular similar in structure to talc (43). There have also been several studies showing migration of talc through the vagina to the ovaries (5). However, at least one of these studies was later disproven due to contamination from talc-containing surgical gloves (44), and several more recent occupational studies have favored the migration of inhaled talc particles from the lung to the ovary (45).

Although early studies showed an association between epithelial ovarian cancer and life-long talc powder use, the majority of these studies were case–control studies limited by small sample size, nonsignificant odds ratios, and recall bias (5–7,9,10). Another study showed that only 14% of women with ovarian cancer had any talc exposure (8). Subsequent investigation has included two prospective trials showing no increased risk between talc use and ovarian cancer (12,13). Recent pooled analyses showed a weak but statistically significant association between talc and serous ovarian cancer, but no association with duration or frequency of use (46,47). Of note, the meta-analysis was limited by notable variation in study designs.

While skin moisturizers made up only 10.5% of total cancer cases, they were the product class with the highest number of skin cancer reports (n = 14). Little available biomedical evidence exists in the literature for such an association. A single study in mice demonstrated a higher rate of skin cancer development when topical moisturizers were applied to the skin prior to Ultra-violet B irradiation. The mechanism for such an effect is unclear but has been postulated to involve moisturizer-mediated inflammation and proliferation of DNA-damaged skin (48). However, studies have shown that the application of moisturizers prior to radiation inhibited carcinogenesis (49). Few studies or associations have been observed in humans. Breast cancer was the second most common cancer reported with moisturizers. This association may possibly be explained by studies linking breast cancer with parabens (a common skin product preservative), which have been covered extensively by the media (2,3).

Various circumstances of exposure to hair dyes have been associated in some studies with increased risk of leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and bladder cancer (50–52). Concerning the association between risk of cancer from both occupational and, typically lesser, consumer exposures, the International Agency for Research on Cancer’s (IARC’s) comprehensive review of the literature found “limited evidence” for hair dye carcinogenicity in occupational exposure and “inadequate evidence” for carcinogenicity following personal use (53). There are data indicating that long-term occupational exposure of hairdressers to the aryl amines contained in hair dyes was associated with later development of bladder cancer (50). Since the IARC evaluations were made, additional studies have been published, including, for example, data concerning occupational (54) and personal exposure (55). One other study has indicated that personal use of darker hair dyes and relaxants was linked to estrogen receptor–positive (ER+) and ER- breast cancer (11). Some studies have demonstrated mutagenicity of hair dye chemicals, particularly arylamine p-phenylenediamine (PPD) in conjunction with hydrogen peroxide, in animal models through the formation of reactive oxygen species (56,57). Moreover, PPD acetylation in the skin is thought to play a role in carcinogenesis over time. In the case of bladder cancer, arylamines are again implicated through activation of the cytochrome p450 system that leads to DNA-binding metabolites (58). Despite these data, several meta-analyses have been equivocal, with some showing a positive association with bladder and hematopoietic cancers but not breast cancer (54,55,59–62).

Hair products outside of hair dyes have also been implicated in increased cancer risk. In 2011, the FDA issued warning letters to the manufacturers of certain heated hair treatments, Brazilian blow-out, due to the release of formaldehyde with heat. Formaldehyde is a known carcinogen associated with lung and hematologic malignancies (63–66). Of the nine unique cancers associated with hair products in the CAERS database, only Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, lung cancer, and breast cancer have any supporting reports in the literature. Other cancers reported in the database included thyroid and skin lesions, for which little outside evidence exists.

Policy Implications for Cosmetics Safety and Cancer Risk

The CAERS database has the potential to become a useful cancer epidemiological tool. As it stands, there are significant limitations. The primary need is for broader participation from all stakeholders including physicians and manufacturers. Currently, manufacturers are not required by law to forward adverse events related to cosmetics. As an example, a manufacturer of a hair product had received more than 21 000 adverse event reports directly from consumers that were not forwarded to the FDA. At the time, the FDA had only received 127 reports (67).

As previously mentioned, the data included within the CAERS database contain considerable gaps, particularly in regard to patient demographics and cancer specifics. There are several potential improvements. First, there is a need for more specific cancer subtyping whenever possible. Second, report data would be of greater benefit if reporters were compelled to provide 1) family history, 2) comorbid conditions, and 3) relevant personal behavioral characteristics (eg, smoking history, drug use, alcohol use, tanning bed use). Finally, to potentially control for reporter bias, consumers can be asked to note whether their reports were triggered by a media report.

The above improvements would enable CAERS to be a better surveillance tool. Emerging concerns could be identified earlier, which could facilitate follow-up scientific studies, site visits, and cross-referencing with carcinogens listed by other agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency, National Toxicology Program, and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (68). If a potential risk is identified through CAERS, the FDA and other regulatory bodies could better focus scarce resources on further investigation. Consideration should then be given by manufacturers to add warning labels, change formulations, or alter the recommended frequency of use of cosmetic products when there is demonstration of potential risk. Such warning labels have been suggested for talc powder (69). However, the FDA’s current position is that there is insufficient evidence to warrant this.

Ultimately, CAERS and other databases alone will not be enough to ensure consumer safety. Rather, they should be viewed as an initial step in part of a larger need for greater FDA authority over the cosmetics industry (19). This includes required mandatory manufacturer registration with the FDA and the need for greater funding for regulatory activities. In 2017, the Office of Cosmetics and Colors, the division of the FDA charged with enforcing labeling of cosmetic products, operated with an annual budget of only $13 million to regulate the $62 billion US cosmetics industry (22).

Conclusions

With the ongoing media attention surrounding cosmetics and carcinogenesis, oncologists will continue to face questions from concerned patients. Nonspecific cancer subtyping, lack of comorbid medical condition information, and the risk of reporter bias all limit the current FDA database for cosmetics. Better and broader data collection is necessary if the CAERS database is to become a useful cancer epidemiological tool that can highlight emerging concerns and direct scarce regulatory resources to promote public safety and allay consumer fears. Concomitant investments in toxicology, biomarker discovery, and regulatory science are needed.

Funding

Dr. Xu recognizes support from the Foglia Family Foundation and National Institutes of Health grant T32AR060710.

Notes

Affiliations of authors: Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention, Department of Preventive Medicine (WEF), and Department of Dermatology (SX), Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine (SLJ, EC, MK), Chicago, IL.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Charles AK, Darbre PD.. Combinations of parabens at concentrations measured in human breast tissue can increase proliferation of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. J Appl Toxicol. 2014;335:390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Darbre PD. Aluminium, antiperspirants and breast cancer. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;999:1912–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Darbre PD. Underarm antiperspirants/deodorants and breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(Suppl 3):S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Darbre PD, Aljarrah A, Miller WR, Coldham NG, Sauer MJ, Pope GC.. Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumours. J Appl Toxicol. 2004;241:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Booth M, Beral V, Smith P.. Risk factors for ovarian cancer: A case-control study. Br J Cancer. 1989;604:592–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cook LS, Kamb ML, Weiss NS.. Perineal powder exposure and the risk of ovarian cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;1455:459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cramer DW, Welch WR, Scully RE, Wojciechowski CA.. Ovarian cancer and talc: A case-control study. Cancer. 1982;502:372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harlow BL, Cramer DW, Bell DA, Welch WR.. Perineal exposure to talc and ovarian cancer risk. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;801:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hartge P, Hoover R, Lesher LP, McGowan L.. Talc and ovarian cancer. JAMA. 25014:1844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Whitteore AS, Wu M, Paffenbarger R et al. , . Personal and environmental characteristics related to epithelial ovarian cancer. II. Exposures to talcum powder, tobacco, alcohol, and coffee. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;1286:1228–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Llanos AAM, Rabkin A, Bandera EV.. Hair product use and breast cancer risk among African American and white women. Carcinogenesis. 2017;389:883–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gertig D, Hunter D, Cramer D et al. , . Prospective study of talc use and ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;923:249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Houghton SC, Reeves KW, Hankinson SE et al. , . Perineal powder use and risk of ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;1069:dju208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cosmetic Ingredient Review: an independent panel of scientific and medical experts. Final amended report on the safety assessment of Methylparaben, Ethylparaben, Propylparaben, Isopropylparaben, Butylparaben, Isobutylparaben, and Benzylparaben as used in cosmetic products. Int J Toxicol. 2008;27(Suppl 4):1–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mirick DK, Davis S, Thomas D.. Antiperspirant use and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;9420:1578–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nohynek GJ, Borgert CJ, Dietrich D, Rozman KK.. Endocrine disruption: Fact or urban legend? Toxicol Lett. 2013;2233:295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Willhite CC, Karyakina NA, Yokel RA.. Systematic review of potential health risks posed by pharmaceutical, occupational and consumer exposures to metallic and nanoscale aluminum, aluminum oxides, aluminum hydroxide and its soluble salts. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2014;44(Suppl 4):1–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. American Cancer Society. “Cosmetics.” 2014. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/cosmetics.html. Accessed November 21, 2017.

- 19. Kwa M, Welty L, Xu S.. Adverse events reported to the US Food and Drug Administration for cosmetics and personal care products. JAMA Intern Med. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Department of Justice. Freedom of Information Act. 2016. https://www.justice.gov/oip/doj-guide-freedom-information-act-0. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- 21. FDA. MedWatch voluntary report. 2017. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/medwatch/index.cfm?action = professional.reporting7. Accessed November 8, 2017.

- 22. Califf RM, McCall J, Mark DB.. Cosmetics, regulations, and the public health: Understanding the safety of medical and other products. JAMA Intern Med. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rajiv Shah KET. Concealing danger: How the regulation of cosmetics in the United States puts consumers at risk. Fordham Environ Law Rev. 2011;231:203–272. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vainio H, Wilbourn JD, Sasco AJ et al. , . Identification of human carcinogenic risk in IARC Monographs. Bull Cancer. 1995;82:339–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peto R, Pike MC, Day NE et al. , . Guidelines for simple, sensitive significance tests for carcinogenic effects in long-term animal experiments In: IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Humans. Supplement 2: Long-term and Short-term Screening Assays for Carcinogens: A Critical Appraisal. Lyon: IARC Press; 1980:311–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boberg J, Axelstad M, Svingen T.. Multiple endocrine disrupting effects in rats perinatally exposed to butylparaben. Toxicol Sci. 2016;1521:244–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Manservisi F, Gopalakrishnan K, Tibaldi E.. Effect of maternal exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals on reproduction and mammary gland development in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Reprod Toxicol. 2015;54:110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vineis P, Illari P, Russo F.. Causality in cancer research: a journey through models in molecular epidemiology and their philosophical interpretation, Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2017;14:1742–7622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schulte PA, Perera FP.. Molecular Epidemiology: Principles and Practice. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Christiani DC. Combating environmental causes of cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;3649:791–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Judson RS, Houck KA, Kavlock RJ.. In vitro screening of environmental chemicals for targeted testing prioritization: The ToxCast project. Environ Health Persp. 2010;118:485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.NTP. Tox21. 2015. http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ results/hts/index.html. Accessed May 4, 2015.

- 33. Schmidt CW. TOX 21: New Dimensions of Toxicity Testing. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;1178:A348–A353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schwarzman MR, Ackerman JM, Dairkee SH et al. , . Screening for Chemical Contributions to Breast Cancer Risk: A Case Study for Chemical Safety Evaluation. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;12312:1255–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fisk M, Feeley J.. The lawsuits keep coming for Johnson & Johnson. Bloomberg Businessweek. 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-03-09/the-lawsuits-keep-coming-for-johnson-johnson. Accessed November 10, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Society of Toxicology, Statistical Assessment Service, and Center for Health and Risk Communication. Center for Media and Public Affairs. The Media and Chemical Risk: Toxicologists’ Opinions on Chemical Risk and Media Coverage. Media Monitor 2009. 23(2). https://cmpa.gmu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/2009-1.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- 37. Camargo MC, Stayner LT, Straif K et al. , . Occupational exposure to asbestos and ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;1199:1211–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Keal EE. Asbestosis and abdominal neoplasms. Lancet. 1960;27162:1211–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wignall BK, Fox AJ.. Mortality of female gas mask assemblers. Br J Ind Med. 1982;391:34–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Harlow BL, Hartge PA.. A review of perineal talc exposure and risk of ovarian cancer. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1995;212:254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cramer DW, Vitonis AF, Terry KL, Welch WR, Titus LJ.. The association between talc use and ovarian cancer: A retrospective case-control study in two US states. Epidemiology. 2016;273:334–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goldner RD, Adams DO.. The structure of mononuclear phagocytes differentiating in vivo. III. The effect of particulate foreign substances. Am J Pathol. 1977;892:335–350. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang Y, Mikhaylova L, Kobzik L, Fedulov AV.. Estrogen-mediated impairment of macrophageal uptake of environmental TiO2 particles to explain inflammatory effect of TiO2 on airways during pregnancy. J Immunotoxicol. 2015;121:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Henderson WJ, Griffiths K.. Talc on surgeons' gloves. Br J Surg. 1979;668:599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Muscat JE, Huncharek MS.. Perineal talc use and ovarian cancer: A critical review. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;172:139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Berge W, Mundt K, Luu H, Boffetta P.. Genital use of talc and risk of ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Terry KL, Karageorgi S, Shvetsov YB et al. , . Genital powder use and risk of ovarian cancer: A pooled analysis of 8,525 cases and 9,859 controls. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) .2013;68:811–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lu YP, Lou YR, Xie JG.. Tumorigenic effect of some commonly used moisturizing creams when applied topically to UVB-pretreated high-risk mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;1292:468–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lh Kligman AK. Petrolatum and other hydrophobic emollients reduce UVB-induced damage. J Dermatol Treat. 1992;31:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bolt HM, Golka K.. The debate on carcinogenicity of permanent hair dyes: New insights. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2007;376:521–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. de Sanjosé S, Benavente Y, Nieters A et al. , . Association between personal use of hair dyes and lymphoid neoplasms in Europe. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;1641:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Huncharek M, Kupelnick B.. Personal use of hair dyes and the risk of bladder cancer: Results of a meta-analysis. Public Health Rep. 2005;1201:31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Some aromatic amines, organic dyes, and related exposures. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2010;99:v–vii, 1–412. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54. Harling M, Schablon A, Schedlbauer G, Dulon M, Nienhaus A.. Bladder cancer among hairdressers: A meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2010;675:351–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mendelsohn JB, Li QZ, Ji BT et al. , . Personal use of hair dye and cancer risk in a prospective cohort of Chinese women. Cancer Sci. 2009;1006:1088–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ames BN, Kammen HO, Yamasaki E.. Hair dyes are mutagenic: Identification of a variety of mutagenic ingredients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;726:2423–2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sontag JM. Carcinogenicity of substituted-benzenediamines (phenylenediamines) in rats and mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981:663:591–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lucia Miligi AC, Benvenuti A, Veraldi A et al. , . Personal use of hair dyes and hematolymphopoietic malignancies. Arch Environ Occupat Health. 2010;605:249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Grodstein F, Hennekens CH, Colditz GA et al. , . A prospective study of permanent hair dye use and hematopoietic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;8619:1466–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. La Vecchia C, Tavani A.. Epidemiological evidence on hair dyes and the risk of cancer in humans. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1995;41:31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Takkouche B, Etminan M, Montes-Martínez A.. Personal use of hair dyes and risk of cancer: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;29320:2516–2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thun MJ, Altekruse SF, Namboodiri MM et al. , . Hair dye use and risk of fatal cancers in U.S. women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;863:210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Beane Freeman LE, Blair A, Lubin J et al. , . Mortality from lymphohematopoietic malignancies among workers in formaldehyde industries: The National Cancer Institute Cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;10110:751–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Maneli MH, Smith P, Khumalo NP.. Elevated formaldehyde concentration in “Brazilian keratin type” hair-straightening products: A cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;702:276–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pierce JS, Abelmann A, Spicer LJ et al. , . Characterization of formaldehyde exposure resulting from the use of four professional hair straightening products. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2011;811:686–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Schwilk E, Zhang L, Smith MT et al. , . Formaldehyde and leukemia: An updated meta-analysis and evaluation of bias. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;529:878–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. FDA. FDA information for consumers about WEN by Chaz Dean Cleansing Conditioners. 2017. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/productsingredients/products/ucm511631.htm. Accessed August 15, 2017.

- 68.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fourth national report on human exposure to environmental chemicals. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/index.html. Accessed October 13, 2017.

- 69. Cohen R. Genital talc boosts ovarian cancer risk in study. Reuters. March 3, 2016. [Google Scholar]