Abstract

Objective. To explore the ethnocultural influences on the chronic pain experience in three culturally and linguistically diverse communities in Australia.

Methods. Six focus groups were conducted with 34 women and 7 men (ages 36–74 years) who self-identified as Mandaean, Assyrian or Vietnamese. A purposive sample of community-dwelling adults living with chronic pain (daily pain >3 months) was recruited from community organizations. Participants were asked broadly about the meanings of chronic pain, acceptance, ethnocultural community expectations and approaches to pain management. A standardized interview collected sociodemographic and symptom data for descriptive purposes.

Results. Inductive thematic analysis yielded a multidimensional web of themes interrelated with the pain experience. Themes of ethnocultural identity and migrant status were intertwined in the unique explanatory model of pain communicated for each community. The explanatory model for conceptualizing pain, namely biopsychosocial, biomedical or a traditional Eastern model, framed participants’ approaches to health seeking and pain management.

Conclusions. Chronic pain is theoretically conceptualized and experienced in diverse ways by migrant communities. Knowledge of cultural beliefs and values, alongside migration circumstances, may help providers deliver health care that is culturally responsive and thereby improve outcomes for migrant communities with chronic pain.

Keywords: chronic pain, qualitative research, cultural and linguistic diversity, ethnicity, culture

Key messages

Understandings of chronic pain are ethnoculturally constructed, varying for diverse communities.

The explanatory model of pain is shared among community members and influences their coping mechanisms.

Ethnocultural and migration influences need to be incorporated into chronic pain assessment and management.

Introduction

Communities from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds represent a substantial and growing proportion of society in many countries [1]. As a consequence, health care providers must interact with and manage clients from ethnocultural backgrounds different from their own. Such cross-cultural interactions may be complicated by coexisting, potentially discrepant beliefs, values and explanatory models of health and illness between provider and patient [2]. Given that a patient’s experience of health and illness is framed by social and cultural constructions, health care providers must be able to recognize and incorporate the views and values of culturally diverse patients [2].

Chronic pain is one condition where the disease burden disproportionately affects CALD, migrant, refugee and low socioeconomic status communities [3–5]. While an abundance of clinical and experimental research supports that pain is perceived and experienced differently according to ethnoculture, research exploring mechanisms behind these differences is limited [3, 6]. Further, there is a paucity of high-quality research into pain management approaches inclusive of ethnoculturally diverse and migrant communities [7]. Therefore research is required to understand the cultural and social underpinnings of chronic pain among CALD communities.

Discordant explanatory frameworks for pain between patients and health care providers is one domain thought to impact on management decisions and outcomes for patients with chronic pain [8, 9]. While the biopsychosocial model is accepted as the most appropriate approach for managing chronic pain in the Western world, not all patients or communities operate under this framework. In some communities, psychological influences are rejected in favour of biological explanations, while in others, spiritual, social and environmental factors are considered causative [2, 9–11]. Beliefs about the nature and cause of an illness can influence help-seeking behaviours and engagement with therapies [10, 12]. Failure to recognize culturally bound beliefs about pain may be one reason why suboptimal clinical outcomes have been observed in CALD populations [3, 7].

While suboptimal outcomes in CALD populations are common in many areas of health care, research highlights that patients’ perceive that the quality of care is better when health care providers respect and learn about the cultural practices of patients [13, 14]. Despite this, there is limited information to guide providers in the most effective ways to adapt their assessment and management practices to respect the cultural values of their patients, particularly in the area of chronic pain [7, 15]. Therefore research is required to inform health care providers about the ethnocultural dimensions underpinning the construction of pain and pain experiences in order for pain management to respond to the needs of CALD societies. Thus this research sought to explore the ethnocultural dimensions influencing how chronic pain is constructed and experienced in three CALD communities (Vietnamese, Assyrian and Mandaean) with the overall goal to inform recommendations for the development of culturally responsive pain management practices.

These three CALD communities were selected, as they are prominent in Australia and internationally, dispersed from their homeland largely due to conflict. The Vietnamese community is one of the largest Asian community’s in Australia, the USA and Canada [16]. Much of this growth can be attributed to the refugee crisis following the Vietnam War [17]. Similarly, Assyrian and Mandaean dispersion was propelled by conflict in Iraq. Internationally, Iraqis are the second largest nationality seeking asylum in industrialized countries [18] and represent large communities in Australia, Norway, Canada and the USA [19]. Given the prominence of Vietnamese, Assyrian and Mandaean communities in Australia and internationally, this exploration focused on CALD communities’ experience of pain in these cohorts.

Methods

Design

This research was an exploration of how chronic pain is constructed, accepted and experienced by Vietnamese, Assyrian and Mandaean communities in Australia. Focus groups were used, as they allow for the generation of collective perspectives and are particularly useful when investigating CALD and/or vulnerable populations [20, 21]. The topic guide was developed by the research team, modelled on previous research with CALD communities [2, 22] and piloted with a group of physiotherapists and volunteer community leaders. The topic guide included 11 questions derived from four broad topics: (i) meanings of chronic pain, (ii) pain acceptance, (iii) community expectations and (iv) pain management (Supplementary Data, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice). The South-West Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee and the Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study protocol. All participants provided written, informed consent.

Participants

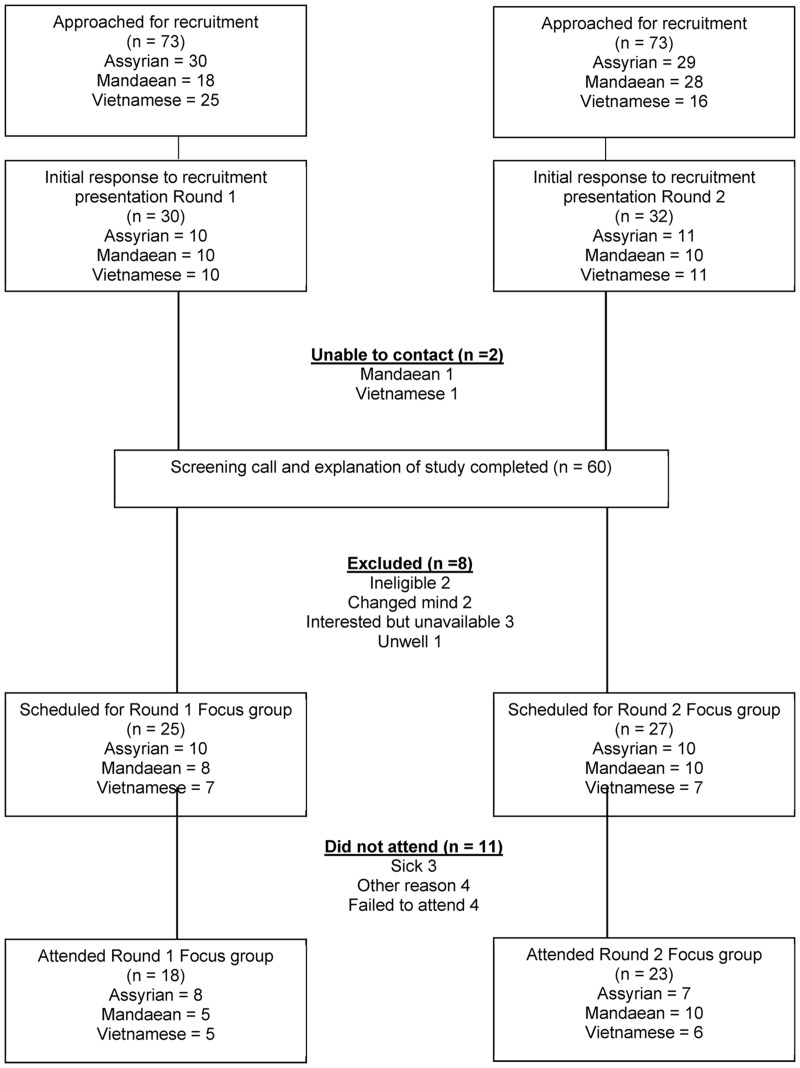

Participants were drawn from community venues in south-west Sydney using purposive criterion sampling [23, 24]. Venues were selected by community leaders to give access to potential participants’ representative of patients accessing chronic pain services in south-west Sydney (age, gender and socioeconomic characteristics). Following project announcements, interested community members consented to be contacted by the research team to establish eligibility. Participants were included if they were adults (>18 years), with a diagnosis of chronic pain (daily pain >3 months), self-identifying [25] as a first-generation member of the Assyrian, Mandaean or Vietnamese ethnocultural community and willing to attend and participate in a focus group discussion. There were no specific exclusion criteria. Figure 1 outlines the flow of participant recruitment. A description of the three communities can be found in the Supplementary Data, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice.

Fig. 1.

Flow of participant recruitment

Procedure

Initially, one focus group was conducted with each community in the language of the participants (Arabic for the Mandaean community, Assyrian and Vietnamese). One trained multicultural health worker representing each community facilitated the session, assisted by a bilingual physiotherapist and supported by a separate observer who recorded participants’ interactions and non-verbal communications [26, 27]. Each participant also completed a short individual interview with researchers to collect sociodemographic and pain characteristics. All focus groups were audio recorded, translated and transcribed by an independent translation agency. The facilitator and bilingual physiotherapist reviewed all transcripts to ensure accuracy in the transcription and translation to English. Any discrepancies were resolved via discussion and review of the audio recording. Data analysis commenced following the first round of focus groups, with plans for further rounds until saturation of data was reached [28, 29]. A debriefing session, using the transcripts, was completed with the facilitators and physiotherapists prior to subsequent focus groups. Member checking was achieved through participant review of the transcripts for accuracy and a facilitated discussion of the themes and concepts that emerged following analyses [30]. This was performed for each community separately and facilitated by the multicultural health worker and primary researcher.

Data analysis

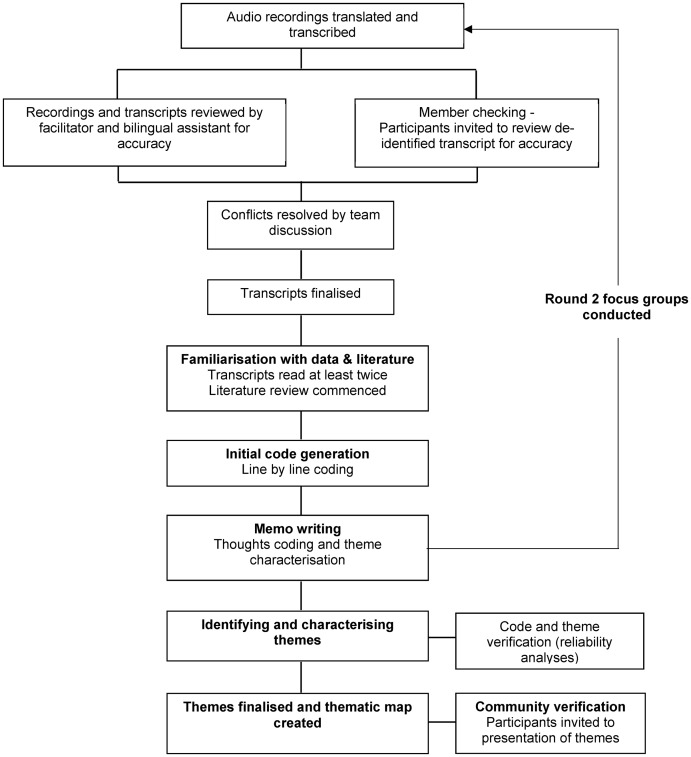

An inductive thematic analysis approach was used [31]. Data familiarization was conducted by all authors independently, focusing on eliciting meaning and patterns in the data [31] (Fig. 2). Simultaneously, a literature review was undertaken to sensitize authors to potential themes embedded in the data [31]. The entire dataset was organized by the first author into meaningful groups with coding, using the NVivo software package (QSR International, Doncaster, VC, Australia). To avoid selective perception of the first author, two authors from different disciplines (physiotherapy and social science) independently coded extracts of the dataset (multi-analyst triangulation) [30]. A codebook was then created and revised through each stage of the analysis [32]. Memo writing was performed to document the process of theme emergence. The codebook was finalized and assessed for consistency of application across the research team and reliability was established by calculating Cohen’s κ, using NVivo. Reflection on codes and their components was performed to facilitate understanding of implicit, unstated and condensed meanings within the dataset [32]. All authors reached consensus on patterned meanings, or themes, identified throughout the process of analysis and these were grouped into thematic categories [32].

Fig. 2.

Steps involved in data collection and analysis

A second round of focus groups was conducted with each community and analysed as per the previous steps. A critical issue in assessing data saturation in non-probabilistic sampling is providing a measure of the overall relative importance of the codes that emerge. At a certain point, additional focus groups would not result in uncovering any new information about the ethnocultural influences on chronic pain. Thus we determined that saturation had been reached when (i) no new themes emerged from a successive focus group with a specific community and (ii) when there was adequate internal consistency between the relative importance of codes. The latter followed a method outlined by Guest et al. [28], which is a novel utilization of the Cronbach’s α coefficient. No new codes emerged between the first and second focus group for each ethnocultural community, satisfying the criteria for theoretical saturation [28]. Second, this was supported by investigating the variability of code frequency between the first and second focus group, using Cronbach’s α [28]. Cronbach’s α was calculated as 0.82 for the Mandaean community, 0.79 for the Assyrian community and 0.87 for the Vietnamese community, indicating consistency of codes between round one and two.

Results

Six focus groups with between 5 and 10 participants, with a mean age of 60 years (range 36–74), were conducted. Table 1 displays the demographic information of the 41 participants. Despite an attempt to recruit an equal number of men and women, a number of men (n = 13) declined to participate or did not attend the scheduled session. Therefore 83% of the final sample was women. The average duration of time in Australia was less for the Mandaean community compared with the Assyrian and Vietnamese communities. Further, the majority of Mandaeans identified as refugees, in contrast to the Assyrian and Vietnamese participants. Finally, the sample represents a low socioeconomic status cohort from each community. Socioeconomic and pain characteristics reflect the typical demographics of patients in these communities who access pain services in south-west Sydney.

Table 1.

Participant demographic characteristics

| Characteristics | Mandaean (n = 15) | Assyrian (n = 15) | Vietnamese (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (s.d.), years | 60 (5.8) | 65 (9.3) | 56 (10.5) |

| Female, n (%) | 14 (93) | 10 (67) | 10 (91) |

| Length of time in Australia, mean, years | 7.6 | 14.5 | 25 |

| Migration circumstances, n (%) | |||

| Voluntary migrant | 2 (13) | 10 (67) | 9 (82) |

| Refugee | 13 (87) | 5 (33) | 2 (18) |

| Marital status–married, n (%) | 9 (60) | 14 (93) | 5 (46) |

| Level of education, n (%) | |||

| No school or primary only | 5 (33) | 7 (47) | 2 (18) |

| Secondary | 4 (27) | 4 (26.5) | 6 (55) |

| Tertiary | 6 (40) | 4 (26.5) | 3 (27) |

| Number of pain areas ≥5, n (%) | 11 (73) | 12 (80) | 10 (91) |

| Duration of pain ≥5 years, n (%) | 14 (93) | 13 (87) | 5 (45.5) |

| Work status, n (%) | |||

| Unemployed due to pain | 13 (87) | 10 (67) | 5 (46) |

| Retired | 0 | 3 (20) | 3 (27) |

| Carer or domestic role | 2 (13) | 2 (13) | 3 (27) |

| Receiving pension or benefit | 15 (100) | 15 (100) | 10 (91) |

| Pension or benefit type | |||

| Disability, n (%) | 11 (73) | 7 (47) | 1 (9) |

| Unemployment (pain related), n | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Age pension, n | 0 | 5 | 2 |

| Carer pension/other, n | 2 | 1 | 5 |

n = number of participants. % = percentage within the group.

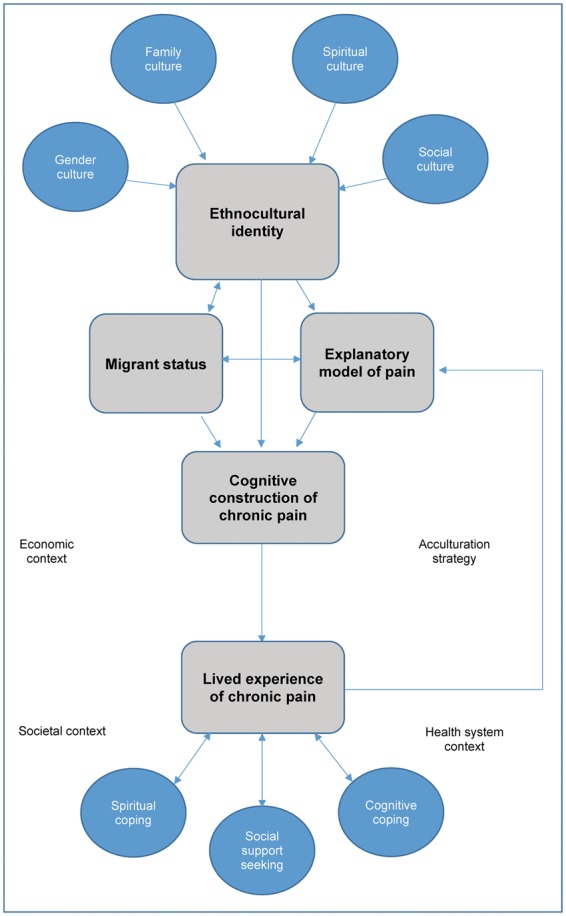

Analyses highlighted multiple dimensions related to the pain experience (Fig. 3). These were classified as input factors about how pain was cognitively constructed and output factors representing the lived experience of pain. Three themes underpinning the construction of the pain experience emerged—ethnocultural identity, migrant status and explanatory model—and were viewed as interrelated. This in turn influenced each community’s lived experience of pain. The subthemes and consistency of code emergence for each theme are displayed in Table 2. The reliability of the codebook across the team members was established with a Cohen’s κ of 0.83.

Fig. 3.

Thematic map of the multidimensional experience of chronic pain for culturally and linguistically diverse communities

Table 2.

Summary of themes

| Theme and subtheme | Mandaean | Assyrian | Vietnamese |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnocultural identity | |||

| Spiritual culture |

|

|

N/A |

| Gender and family culture |

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Social–community connectedness |

|

|

|

| Migrant or refugee identity | |||

| Cultural and religious persecution |

|

N/A | N/A |

| Personal turmoil and living with war |

|

|

N/A |

| Adaptation to life as a migrant/refugee |

|

|

N/A |

| Health framework | |||

| Traditional beliefs | N/A | N/A | Pain can be caused by an excess or deficiency in ‘âm or du´o´ng’: When I was still a child, my friends advised me not to take off your shoes when you get home after a long time walking in sunshine. Because if you take off your shoes right after they been in hot temperature, coldness from the floor may attack and absorb in your body (V1, p8, female). |

| Imbalance occurs by eating too hot food (V1, p6, female), too cold food (V1, p6 and p10, female), too much sour food (V1, p8, female) and too much fruit (V1, p10, female). | |||

| Biological/pathological |

|

|

|

| Social | Social pressures such as financial hardship and inability to fulfil traditional roles had a direct impact and could cause pain. | N/A | N/A |

| Psychological | Psychological cause:

|

Psychological comorbidity:

|

N/A |

| The lived experience of pain | |||

| Spiritual coping | Active religiousness—performing rituals to cleanse the body and mind: I practice my daily religious rituals which me feel relaxed from within and comforts my pains; you just raise your hand and supplicate. The Mandeni religion is very strong and I believe in it. I love my religion very much (M1, p4, female). | Passive religiousness—praying and hoping: she will leave it in God’s capable hands, because he is the strongest doctor. Even the doctors say God is more powerful he is healing people (A1, p17, female). | N/A |

| Social support seeking | Turning to the community and religious leaders for spiritual and emotional support:

|

Seeking out and expecting emotional support from others: a sister should be there to help me, to comfort me emotionally (A2, p39, female). | Actively seeking out solutions and guidance from others within the community: I tell them all [referring to others within the community], I don’t hide anything. Because I hope that if someone knows about this pain, he or she will tell me how to cure it (V1, p9, female). |

| Cognitive coping | Distraction—engaging in activities, particularly community functions, to direct attention away from the pain: My opinion is that people should help themselves by joining good people or communities, go out a little or if unable to go out, reading a newspaper, on the computer a little, watching TV…etc. So that all these elements help him forget a bit about the pain (M2, p20, female). | Distraction—engaging in activities, particularly community functions, to direct attention away from the pain: We should ourselves try mixing with our community, may it be in our churches, at different functions and meetings because by doing this we tend to forget about our medical conditions (A1, p17, female). | Problem focused coping— Identifying âm and du´o´ng imbalances and directing efforts towards resolving these:

|

M1 or M2, Mandaean focus group 1 or 2; A1 or A2, Assyrian focus group 1 or 2; V1 or V2, Vietnamese focus group 1 or 2; p, participant number; N/A, not applicable (i.e. theme did not apply for this community).

Ethnocultural identity

Participants constructed meanings of chronic pain collaboratively through discussions and interactions. In doing so, a communal representation of ethnocultural identity was communicated. Specific subthemes of ethnocultural identities included spiritual culture, gender culture, family culture and social culture. Quotes supporting each are displayed in Table 2.

Spiritual culture

The Assyrians and Mandaeans framed religion and spirituality as fundamental aspects of their ethnocultural identities, but this did not emerge as a theme in the Vietnamese focus groups. While the Assyrian and Mandaean communities had different spiritual beliefs and practices, spirituality was intertwined in their lived experience of pain and the coping strategies adopted. For example, Mandaeans practiced rituals such as baptism involving water, considered to be their life source, to renew connection with their community and alleviate pain. In contrast, Assyrians’ spirituality offered a distraction and sense of solace from their pain, with their enduring faith offering ‘hope that anything can be treated’ (Assyrian focus group 1, participant 11, male). For both communities, religious leaders and institutions were valuable sources of emotional support and mediated their personal relationships with the spiritual world. Finally, spirituality offered both communities the opportunity to give perspective to their suffering.

Gender and family culture

For all three communities, cultural roles were conveyed by obligations to their family and social-gender norms dictating appropriate behaviour. Notably, all communicated traditional gender roles with the expectation that women should act as a homemaker, attending to the needs of the family independent of her own health situation, while the role of men is as providers. The family unit was emphasized as an important aspect of culture for all three communities. Participants also noted the status of elders within their communities and expectations for them to be cared for and their instructions followed. Quotes presented in Table 2 reflect the traditional, collectivist views of all three communities. As such, the identity of the individual is entwined within their role in the family and wider community. Accordingly, the needs of an individual experiencing pain are viewed second to the needs of the family and wider community.

Social culture

Community connectedness, referring to a person’s sense of belonging within the community, emerged for all communities. Rather than an individualistic point of view, Mandaeans, Assyrians and Vietnamese integrated sense of self through their relationships with others and their community status. For the Vietnamese community, there was an appreciation of societal roles and social hierarchy, with participants acknowledging respect for elders and those in positions of social standing, such a health professionals [33]. At the heart of this social organization is the benefit to the community such that knowledge and resources are shared, often in indirect and non-confrontational ways through the use of proverbs.

In contrast, Assyrian and Mandaean participants’ sense of community connectedness was underpinned by religious beliefs and values. Religious venues provide an access point for community engagement, giving opportunities for Assyrians and Mandaeans to use spirituality to cope with health conditions. Further, participants from Mandaean and Assyrian communities projected their identities as communal in nature, using the collective ‘we’ and ‘our’, rather than self, when referring to core values and customs. As such, the experience of pain is viewed from a communal perspective.

Health framework

Varying understandings of how health and pain are framed were conveyed and grouped into three broad frameworks: biomedical, biopsychosocial and traditional medicine approaches. The Assyrians communicated a dominant biomedical framework for understanding pain. That is, pain is attributed to organic pathology, and while other factors, such as psychological health, influence the consequences of the disease, they are not related to the development or manifestation of pain. Conversely, Mandaeans communicated a biopsychosocial approach to illness. Pain was framed as multifactorial, influenced by pathology, psychological factors and socioeconomic circumstances. Specifically, psychological pressures and social challenges related to refugee identity were highlighted and, in contrast to the Assyrians, constituted explanations for, rather than consequences of, pain symptoms. In contrast, the Vietnamese community conveyed a hybrid framework for the understanding of pain that was a combination of traditional Chinese medicine and biomedical views. Founded by principles of âm and du´o´ng harmony [34], participants reflected that imbalances in the body, such that could occur by eating ‘too hot food’ (Vietnamese 1, participant 6, female) or ‘too cold food’ (Vietnamese 1, participants 6 and 10, female), could cause pain. Alongside this traditional framework, Vietnamese participants also accepted pathological diagnoses for pain and illness.

Migrant status

The Mandaean and Assyrian communities emphasized the influence of the migration experience on their pain experience, while for the Vietnamese community this was not an emerging theme. For the Mandaean community, the term ‘refugee’ was prominent in their ethnocultural identity. Cultural and religious persecution underpinned their refugee status and not only had a significant influence on the development of pain, but served as a reminder of their battle for ethnocultural preservation. Further, the Mandaean and Assyrian communities emphasized that their perspectives on pain and health were framed by past experiences in Iraq and their current status as a migrant or refugee. Both communities described personal turmoil, including loss of loved ones, and experiences of conflict, displacement and persecution. Importantly, participants emphasized this was not a personal trauma, but a cultural and collective experience.

The lived experience of pain

The ways in which each community managed their pain were intrinsically related to both their ethnocultural identity and their explanatory model of pain. Spirituality, an important component of ethnocultural identity for the Assyrians and Mandaeans, was used as a coping strategy in different ways. For the Mandaean community, this was framed in an active context whereby participants performed rituals to help relax their body and mind. Conversely, for the Assyrian community, spiritual coping was passively used, characterized by praying and hoping. In a similar manner, cognitive coping took on different forms. Both the Assyrians and Mandaeans used community engagement as a means to direct attention away from their pain, while for the Vietnamese community, deliberate efforts were made to identify and subsequently remedy the specific âm and du´o´ng imbalance. Finally, consistent with the three communities’ collectivist natures previously discussed, social support seeking was an important means for living and coping with pain.

Discussion

This article is the first to explore ways in which chronic pain is framed and experienced by individuals from three CALD communities in Australia. In doing so, this research adds to the body of literature that speaks to the non-homogeneous and fluid nature of ethnoculture, recognizing multiple and intertwining variables including ethnicity, gender, religion, role category and/or social and community group membership (Fig. 3). An individual may draw concurrently from a multitude of cultural identities to frame their understanding of health and illness. The relative contribution of each cultural variable to an individual’s experience of pain will vary, being influenced by socio-environmental contexts. This in turn impacts the explanatory model of disease that will manifest in different ways [2]. Skilful inquiry into these relative contributions will enable health care providers to approach pain management with sensitivity to the diversity of culture, while respecting the individual and their unique illness narrative.

Skilful inquiry should be underpinned by familiarization with the beliefs and practices of prominent ethnocultural communities, sensitizing health care providers to the ways ethnocultural identity may manifest and influence pain. Participants in all communities reflected that gender and family identity played significant roles in the experience of pain and coping methods. For some participants, gender and family roles strengthened their resolve to ‘face the pain’ (Vietnamese focus group 2, participant 30), while others communicated loss of identity related to an inability to fulfil this role. Inability to fulfil social and cultural roles has been associated with loss of identity and higher levels of psychological distress [35] and is important to address in pain management. In a similar manner, recognition of the therapeutic benefit of unity and sense of belonging fostered by collectivist ethnocultural communities should be cultivated [36–38]. Mandaean and Assyrian communities emphasized that maintenance of networks with the community were important for both preserving their ethnocultural identities and coping with pain, consistent with previous research with Middle Eastern migrants [38]. Importantly, these networks served as points of access to information about health services and a formal structure for social support. Such community networks can be valuable resources for health care providers seeking to engage CALD patients in active behaviour change by fostering acceptance for treatment concepts [36].

Spiritual identity was an important part of patients’ pain narratives, reinforcing known associations between spirituality and chronic pain [39, 40]. Spiritual beliefs should be important considerations for health care providers, as they may facilitate or impede engagement with pain management therapies. For example, the use of active spiritual coping by Mandaean participants could be said to promote an internal locus of control and be therapeutic. Conversely, the passive spiritual coping adopted by the Assyrians may impede providers attempts to promote patient self-management [39]. Given that evidence suggests that positive spirituality may promote psychological and physical well-being and provide a means for coping with chronic pain [39, 41], health care providers may want to adopt practices to facilitate assessment of the pain-relevant aspects of a patient’s spirituality. Indeed, McCord et al. [42] reported chronic pain was a condition, among other health diagnoses, where patients from a variety of ethnocultural backgrounds welcomed spiritual discussion by their health care providers. Thus, in keeping with principles of patient-centred care, health care providers should approach patients holistically, attending to cultural and spiritual dimensions in addition to the physical and psychological ones.

Incorporation of a patient’s worldview into therapeutic decision making requires an ability to unravel the explanatory framework for a patient. A patient’s explanatory model dictates their health and illness behaviour and influences their satisfaction and utilization of health care [8, 43]. Our research highlighted that members of the same ethnocultural community share explanatory frameworks, represented by similarities in their narrative of causation, course and consequences of chronic pain. These explanatory frameworks appear to be influenced by ethnocultural identity, migration experience, personal experience and the socio-environmental context within which they are experiencing pain. For example, the Vietnamese explanatory framework could be attributed to a number of potential influences, including Vietnam’s traditional Chinese medicine foundations, the prominent use of Western biomedicine in Vietnam and acculturative influences from living in a Western society [43–45]. Thus health care providers need to look beyond traditional cultural beliefs and explore the individual patient’s acculturative influences and personal experiences in their construction of chronic pain explanatory frameworks.

The degree of patient alignment with the current biopsychosocial framework is an important consideration for providers attempting to engage patients with psychosocial therapies. The Mandaean community was the only community that iterated psychosocial elements as causative of chronic pain, while the Assyrians, a community from a similar geographic and national culture as Mandaeans, presented a predominantly biomedical view of pain. Importantly, the Vietnamese did not associate psychological health with chronic pain. Such contrasting views highlight a need for caution among health care providers adopting psychosocial treatments. For example, a Vietnamese patient may find attempts to establish a link between psychological health and chronic pain confronting, given the stigma associated with mental illness in traditional Vietnamese culture [46, 47]. Similarly, Assyrians, like many Middle Eastern ethnocultural communities, may not recognize, accept or engage in psychological treatments [48, 49]. Thus health care providers should approach therapeutic encounters with the flexibility to reframe pain management approaches in ways that are ethnoculturally acceptable.

The process of migration and subsequent status as a migrant or refugee influenced the three CALD communities in different ways. For the Vietnamese community, identification as a migrant or refugee did not appear to relate to their experience of pain, but was expressed to different degrees by Assyrian and Mandaean participants. The relative importance of this theme may relate to the duration of settlement in Australia and the degree of social adjustment. The Vietnamese community had, on average, a longer time in Australia, while the Mandaean community had the shortest. Such differences argue for caution when approaching CALD migrant communities with chronic pain. It is not appropriate to assume that migration is a significant influence on pain for all migrants. Further, the length of time in a country may either dilute cultural identity or strengthen it according to an individual’s degree of acculturation [50]. Therefore providers should feel comfortable to inquire into the migration history to ascertain the extent that migration and related stressors may contribute to the individual’s illness experience.

Research focusing on pain and cultural diversity is dominated by quantitative studies focusing on pathology. Thus the qualitative literature in this field is in its infancy, with recruitment of hard-to-reach or hidden populations presenting a challenge to research [7, 51]. To meet this challenge, we used non-random purposive sampling. While this has provided rich and valuable data, it is not possible to generalize the findings to the broader community. Based on the limited sample, it is possible that community members with different sociodemographic characteristics may have different beliefs and attitudes. Further, while health behaviours and explanatory models of disease vary according to ethnoculture, ethnoculture is not the sole determinant of health behaviours and health outcomes. Rather, ethnoculture is one factor among a number of variables, including sociodemographic factors, influencing health beliefs and behaviours. Finally, the findings are not intended to be authoritative regarding Assyrian, Mandaean and Vietnamese approaches to chronic pain. To interpret the findings in this manner would perpetuate ethnocultural stereotypes that assume any patient who identifies as Mandaean, Vietnamese or Assyrian operates with a core set of static beliefs linked to ethnocultural identification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by a research scholarship from the Ingham Institute and South Western Sydney Local Health District Research Committee. The authors acknowledge the support of the Fairfield and Liverpool Multicultural Health Unit and the bilingual physiotherapists from each centre that assisted with the project. Special thanks to the participants and the Mandaean, Assyrian and Vietnamese communities for their immense contribution.

Funding: This work was supported by a research scholarship awarded to the primary author from South West Sydney Research and the Ingham Institute. The primary author is the recipient of a Sir Robert Menzies Memorial Research Scholarship in the allied health sciences from the Menzies Foundation.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice Online.

References

- 1. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Migration in Figures. http://www.oecd.org/els/mig/World-Migration-in-Figures.pdf (22 February 2015, date last accessed).

- 2. Kleinman A. The illness narratives: suffering, healing, and the human condition. New York: Basic Books, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R.. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain 2009;10:1187–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kurita GP, Sjogren P, Juel K, Hojsted J, Ekholm O.. The burden of chronic pain: a cross-sectional survey focussing on diseases, immigration, and opioid use. Pain 2012;153:2332–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kellner U, Halder C, Litschi M, Sprott H.. Pain and psychological health status in chronic pain patients with migration background—the Zurich study. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rahim-Williams B, Riley J, Williams A, Fillingim R.. A quantitative review of ethnic group differences in experimental pain response: do biology, psychology, and culture matter? Pain Med 2012;13:522–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brady B, Veljanova I, Chipchase L.. Are multidisciplinary interventions multicultural? A topical review of the pain literature as it relates to culturally diverse patient groups. Pain 2016;157:321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frantsve L, Kerns R.. Patient-provider interactions in the management of chronic pain: current findings within the context of shared medical decision making. Pain Med 2007;8:25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scheermesser M, Bachmann S, Schamann A, Oesch P, Kool J.. A qualitative study on the role of cultural background in patients’ perspectives on rehabilitation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lynch E, Medin D.. Explanatory models of illness: a study of within-culture variation. Cogn Psychol 2006;53:285–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eccleston C, Williams AC, Rogers WS.. Patients’ and professionals’ understandings of the causes of chronic pain: blame, responsibility and identity protection. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cornally N, McCarthy G.. Help-seeking behaviour for the treatment of chronic pain. B J Community Nurs 2011;16:90–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Majumdar B, Browne G, Roberts J, Carpio B.. Effects of cultural sensitivity training on health care provider attitudes and patient outcomes. J Nurs Scholarsh 2004;36:161–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Horvat L, Horey D, Romios P, Kis-Rigo J.. Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;5:CD0094505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brady B, Veljanova I, Chipchase L.. Culturally informed practice and physiotherapy. J Physiother 2016;62:121–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Trends in International Migrant Stock: Migrants by Destination and Origin. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates15.shtml (12 January 2016, date last accessed).

- 17. Chung R, Bemak F.. Lifestyle of Vietnamese refugee women. J Indiv Psychol 1998;54:373–84. [Google Scholar]

- 18. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. UNHCR Asylum Trends 2014: Levels and trends in industrialized countries. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations, 2015. http://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/551128679/asylum-levels-trends-industrialized-countries-2014.html (10 October 2015, date last accessed).

- 19. Jamil H, Nassar-McMillan SC, Lambert RG.. Immigration and attendant psychological sequelae: a comparison of three waves of Iraqi immigrants. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2007;77:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Halcomb EJ, Gholizadeh L, DiGiacomo M, Phillips J, Davidson PM.. Literature review: considerations in undertaking focus group research with culturally and linguistically diverse groups. J Clin Nurs 2007;16:1000–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Waterton C, Wynne B.. Can focus groups access community views? In: Barbour RS, Kitzinger J, eds. Developing focus group research: politics, theory, and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1999:127–43. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Upshur CC, Bacigalupe G, Luckmann R.. “They don’t want anything to do with you”: patient views of primary care management of chronic pain. Pain Med 2010;11:1791–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Curtis S, Gesler W, Smith G, Washburn S.. Approaches to sampling and case selection in qualitative research: examples in the geography of health. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1001–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ritchie J, Lewis J, Elam G.. Designing and selecting samples In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, eds. Qualitative research practice. A guide for social science students and researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003:77–108. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Okazaki S, Sue S.. Methodological issues in assessment research with ethnic minorities. Psychol Assess 1995;7:367–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kidd PS, Parshall MB.. Getting the focus and the group: enhancing analytical rigor in focus group research. Qual Health Res 2000;10:293–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maynard-Tucker G. Conducting focus groups in developing countries: skill training for local bilingual facilitators. Qual Health Res 2000;10:396–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guest G. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marshall B, Cardon P, Poddar A, Fontenot R.. Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in is research. J Comput Inform Syst 2013;54:11–22. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res 1999;34:1189–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Braun V, Clarke V.. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Macqueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B.. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Field Methods 1998;10:31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nguyen MD. Culture shock—a review of Vietnamese culture and its concepts of health and disease. West J Med 1985;142:409–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Purnell LD. Traditional Vietnamese health and healing. Urol Nurs 2008;28:63–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harris S, Morley S, Barton S.. Role loss and emotional adjustment in chronic pain. Pain 2003;105:363–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Seeman TE. Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes in older adults. Am J Health Promot 2000;14:362–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Attree P, French B, Milton B. et al. The experience of community engagement for individuals: a rapid review of evidence. Health Soc Care Commun 2011;19:250–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kenny S, Mansouri F, Spratt P.. Arabic communities and well being: supports and barriers to social connectedness. Victoria, Australia: Deakin University, 2005:1–125. http://www.deakin.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/232016/VICHEALTH-report-FINAL-print2.pdf (13 December 2015, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rippentrop AE. A review of the role of religion and spirituality in chronic pain populations. Rehabil Psychol 2005;50:278–84. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baetz M, Bowen R.. Chronic pain and fatigue: associations with religion and spirituality. Pain Res Manag 2008;13:383–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Larimore WL, Parker M, Crowther M.. Should clinicians incorporate positive spirituality into their practices? What does the evidence say? Ann Behav Med 2002;24:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McCord G, Gilchrist VJ, Grossman SD. et al. Discussing spirituality with patients: a rational and ethical approach. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:356–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jenkins CN, Le T, McPhee SJ, Stewart S, Ha NT.. Health care access and preventive care among Vietnamese immigrants: do traditional beliefs and practices pose barriers? Soc Sci Med 1996;43:1049–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Armstrong TL, Swartzman LC.. Asian versus western differences in satisfaction with western medical care: The mediational effects of illness attributions. Psychol Health 1999;14:403–16. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Luu TD, Leung P, Nash SG.. Help-seeking attitudes among Vietnamese Americans: the impact of acculturation, cultural barriers, and spiritual beliefs. Soc Work Ment Health 2009;7:476–93. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Abdullah T, Brown TL.. Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: an integrative review. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:934–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Groleau D, Kirmayer LJ.. Sociosomatic theory in Vietnamese immigrants’ narratives of distress. Anthropol Med 2004;11:117–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zander V, Mullersdorf M, Christensson K, Eriksson H.. Struggling for sense of control: everyday life with chronic pain for women of the Iraqi diaspora in Sweden. Scand J Public Health 2013;41:799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Youssef J, Deane FP.. Factors influencing mental-health help-seeking in Arabic-speaking communities in Sydney, Australia. Ment Health Relig Cult 2006;9:43–66. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl Psychol 1997;46:5–34. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Spring M, Westermeyer J, Halcon L. et al. Sampling in difficult to access refugee and immigrant communities. J Nerv Ment Dis 2003;191:813–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.