Abstract

Cancer is mainly caused by somatic genome alterations (SGAs). Precision oncology involves identifying and targeting tumor-specific aberrations resulting from causative SGAs. We developed a novel tumor-specific computational framework that finds the likely causative SGAs in an individual tumor and estimates their impact on oncogenic processes, which suggests the disease mechanisms that are acting in that tumor. This information can be used to guide precision oncology. We report a tumor-specific causal inference (TCI) framework, which estimates causative SGAs by modeling causal relationships between SGAs and molecular phenotypes (e.g., transcriptomic, proteomic, or metabolomic changes) within an individual tumor. We applied the TCI algorithm to tumors from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and estimated for each tumor the SGAs that causally regulate the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in that tumor. Overall, TCI identified 634 SGAs that are predicted to cause cancer-related DEGs in a significant number of tumors, including most of the previously known drivers and many novel candidate cancer drivers. The inferred causal relationships are statistically robust and biologically sensible, and multiple lines of experimental evidence support the predicted functional impact of both the well-known and the novel candidate drivers that are predicted by TCI. TCI provides a unified framework that integrates multiple types of SGAs and molecular phenotypes to estimate which genome perturbations are causally influencing one or more molecular/cellular phenotypes in an individual tumor. By identifying major candidate drivers and revealing their functional impact in an individual tumor, TCI sheds light on the disease mechanisms of that tumor, which can serve to advance our basic knowledge of cancer biology and to support precision oncology that provides tailored treatment of individual tumors.

Author summary

Precision oncology relies on the capability of identifying and targeting tumor-specific aberrations resulting from causative genomic alterations in each tumor. Conventional cancer driver identification methods identify candidate cancer driver genes as those exhibit an alteration frequency significantly above the expected frequency that would occur by random chance in a population of tumor samples. This population-based nature prevents them from performing instance-specific discovery, and alteration frequency does not contain information regarding the functional impact of candidate driver genes identified in this approach. Here, we report a novel Bayesian causal discovery framework, referred to as tumor-specific causal inference (TCI), which identifies candidate driver genes as the ones that bear significant functional impact on cancer-related molecular phenotypes at the individual tumor level. By discovering candidate drivers and their function impact in each individual tumor, TCI analysis reveals information that is of value for both general cancer biology research and precision oncology.

Introduction

Cancer is mainly caused by a variety of SGAs, including, but not limited to, somatic mutations (SMs) [1, 2], somatic DNA copy number alterations (SCNAs) [3, 4], chromosome structure variations [5–7], and epigenetic changes [8–10]. Each tumor hosts a unique combination of SGAs ranging in number from hundreds to thousands, of which only a small fraction contributes to tumorigenesis (drivers), while the rest are non-consequential (passengers). Identifying causative SGAs that underlie different oncogenic processes [11], such as metastasis or immune evasion, in an individual tumor is of fundamental importance in cancer biology and precision oncology [12–14].

Current methods for identifying cancer driver genes concentrate on finding those that have a higher than expected mutation rate in a cohort of tumor samples [15–17]. Some methods focus on specific mutation sites (e.g., mutation hotspots at specific amino acids or within the 3D functional domain of a protein) that likely affect the function of those proteins encoded by the mutant genes [17–22]. These mutation-centric, frequency-based models have successfully identified many major oncogenes and tumor suppressors across cancer types. However, they do not directly determine the functional impact of mutations, because mutation frequency of a gene (either at the gene or at the specific amino acid level) does not directly reflect which molecular or cellular processes will be affected by the altered gene product.

Besides mutations, other SGA events affecting driver genes also contribute to cancer development, such as SCNAs [3, 4, 23], chromosome structure variation [5–7], and epigenetic changes [8–10]. Currently, analyses of SMs, SCNAs, structure variation, and epigenetic data are usually carried out separately, with distinct statistical models for different types of data [1, 2, 16, 24, 25]. Such disconnection is largely due to the lack of a unifying statistical framework that is able to integrate diverse data. Integrating diverse data can provide increased statistical power to detect biological function and to gain biological insights by pooling diverse information to assess the role of a driver gene in oncogenesis. A Bayesian approach has the potential to provide such a unifying framework.

Some recent studies have started to employ a Bayesian framework to infer relationships between cancer driver mutations and other omics changes, such as transcriptomic changes. Razi et al. proposed a hybrid Bayesian method to capture the non-linear regulatory effects on the gene expression levels based on a predefined signaling network [26]. The iDriver is another non-parametric Bayesian framework developed by Yang et al. which models the joint distribution of multiomics data and identified 45 novel driver genes that showed significant deviations from the background in at least one omics data [27]. The above methods employ a Bayesian approach to estimate model parameters, rather than searching for causal networks, which is the focus of the current paper. More recently, Wang et al. developed a Bayesian (regularized) regression model, referred to as rDriver, to model the relationships between mutations and gene expression changes [28]. However, it is a population-based regression method, which does not take into account the tumor-specific changes.

In this study, we designed a general framework based on Bayesian causal modeling and discovery [29–31] that estimates the causal relationships between SGAs and molecular phenotypes observed in an individual tumor [32]. We call it the Tumor-specific Causal Inference (TCI) method. By being Bayesian in design, TCI is flexible in the types of data that define both the SGAs and the molecular phenotypes. By being tumor-specific, TCI is able to model the functional causal relationships between the SGAs and the molecular phenotypes in a given tumor. The tumor-specific nature of the TCI differentiates it from previous methods that aim to detect the association between genomic variations and quantitative traits, in particular, the expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis, which is a population-based method that requires a large number of cases to estimate associations between SGAs and molecular phenotypes across a population of tumors [33, 34]. However, eQTL does not predict the causal influence of SGAs on molecular phenotypes in a given tumor. Identification of SGAs that have a specific functional impact on molecular phenotypes in an individual tumor can help to differentiate candidate driver SGAs from passengers and shed light on the disease mechanism of that tumor, which could guide precision treatment of the tumor.

Results

TCI is an integrative framework for discovering the functional impact of SGAs in an individual tumor

We designed the TCI algorithm to discover the causal relationships between SGAs and DEGs observed in an individual tumor. Specifically, given a tumor t hosting a set of SGAs (SGA_SETt) and a set of DEGs (DEG_SETt), TCI estimates the causal relationships between SGAs and DEGs using a bipartite causal Bayesian network [29–31] (Fig 1). It searches for the tumor-specific causal model Mt with a maximal posterior probability P(Mt|D) given the dataset D (containing SGAs and DEGs). The tumor-specific nature of the TCI model is reflected by the assumption that a molecular phenotype change (e.g., a DEG) observed in a specific tumor should be attributed with a high probability to one of the SGAs observed in the tumor that explains the phenotype well in the dataset D, or alternatively, to a non-specific cause denoted as A0 that collectively represents unmeasured genomic events or non-SGA causes, such as the tumor microenvironment (Detailed description of TCI method is included in S1 Text).

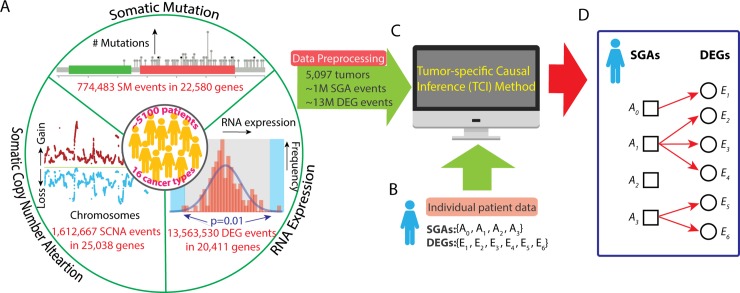

Fig 1. Workflow of TCI analysis.

A. A compendium of cancer omics data is used as the training dataset. Three types of data from the 5,097 pan-cancer tumors were used in this study, including SM data (774,483 mutation events in 22,580 genes), SCNA data (1,612,667 copy number alteration events in 25,038 genes), and gene expression data (13,563,530 DEG events in 20,411 genes). SM and SCNA data were integrated as SGA data. Expression of each gene in each tumor was compared to a distribution of the same gene in the “normal control” samples, and, if a gene’s expression value was outside the significance boundary, it was designated as a DEG in the tumor. The final dataset included 5,097 tumors with 1,364,207 SGA events and 13,549,660 DEG events. B. A set of SGAs and a set of DEGs from an individual tumor as input for TCI modeling. C. The TCI algorithm infers the causal relationships between SGAs and DEGs for a given tumor t and output a tumor-specific causal model. D. A hypothetic model illustrates the results of TCI analysis. In this tumor, SGA_SETt has three SGAs plus the non-specific factor A0, and DEG_SETt has six DEG variables. Each Ei must have exactly one arc into it, which represents having one cause among the variables in SGA_SETt. In this model, E1 is caused by A0; E2, E3, E4 are caused by A1; E5, E6 are caused by A3; A2 does not have any regulatory impact.

Although the indices of the SGAs and DEGs for the patient case shown are sequential, but in general they would indicate different SGAs and DEGs in different tumors.

TCI achieves tumor-specific causal discovery through several innovative approaches. Consider a collection of genomic data (denoted as D) from TCGA, and the data from a new tumor t hosting a set of SGAs (SGA_SETt) and a set of DEGs (DEG_SETt). For a DEG event Ei among the DEG_SETt, TCI aims to identify an SGA Ah among the SGA_SETt that most likely caused Ei, or alternatively, TCI may assign the factor A0 as a non-specific cause. TCI evaluates the posterior probability that Ah causes Ei, which we denote as Ah→Ei, using a Bayesian framework as follows:

| (1) |

where

| (2) |

is a normalization term. From the above equations, one can see that a potential causal SGA Ah only competes with other SGAs observed in the same tumor to explain a molecular phenotype Ei. This allows a less frequent SGA (Ah) to be assigned with high posterior probability as the cause for a changed phenotype (Ei) in a specific tumor, as long as Ah is the most plausible cause when compared with the other SGAs in the same tumor. TCI involves the two terms on the right of the Eq 1: the prior probability that Ah causes Ei, namely, P(Ah→Ei), which can be evaluated at a population-level prior to observing current tumor t, and the conditional probability (aka the marginal likelihood) of data D, P(D|Ah→Ei), given that Ah→Ei, which assesses the functional impact of the causal edges (Supplementary method in S1 Text). This approach allows TCI to integrate useful aspects of a frequency-oriented framework (via the prior probability) and a cellular-function-oriented framework (via the marginal likelihood). An important innovation of TCI is the procedure for evaluating P(D|Ah→Ei), which consist of assessing how well Ah explains the variance of Ei in tumors hosting Ah (aka, “tumors like me”), as well as how well the variance of Ei is explained in tumors do not host Ah. Finally, depending on the composition of SGA_SETt, the tumor-specific prior probability P(Ah→Ei) for the same causal edge between Ah and Ei can be different in different tumors, and therefore tumor-specific (see the Materials and methods section for details).

We applied TCI to analyze data from 5,097 tumors across 16 cancer types in TCGA (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/, S1 Table) to derive 5,097 tumor-specific models (one causal network model per tumor). As a concrete example to illustrate the characteristics of the TCI framework, we present the TCI results of discovering the tumor-specific causes of differential expression of the proto-onco-gene MPL that is commonly observed in tumors. Thrombopoietin receptor MPL (TPO-R), a major regulator of megakaryocytopoiesis and platelet formation, is a proto-oncogene whose ligand (TPO) has been recently identified as a novel candidate marker for ovarian cancer diagnosis and is associated with a poor survival [35, 36]. In recent work, Ismail el al. developed a breast cancer mouse model and found MPL is linked to cell death induction and tumor growth suppression [37]. There is evidence to indicate that the expression of MPL is regulated by the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [38], which includes as members PIK3CA, PTEN, PIK3R1, AKT1 (Fig 2A), and other gene products. The uniqueness of TCI lies at the fact that it seeks to learn the causal relationships between SGAs and DEGs at the individual tumor level. Our assumption is that a DEG is likely to be regulated by one aberrant pathway in a tumor, and such a pathway usually is perturbed by an SGA that affects one member of the pathway. This assumption is based on the observation that SGAs perturbing members of a common pathway rarely co-occur in an individual tumor, which is a phenomenon referred to as mutual exclusivity [39–41]. Thus, tumors with an aberrant PI3K/AKT pathway usually host an SGA in one of these members, although they likely share target genes, e.g., the DEG MPL. A causal discovery algorithm should attribute an MPL DEG event in a tumor to a member SGA of the PI3K/AKT pathway with high probability if one of those SGAs appears in the tumor. Indeed, in the tumors exhibiting differentially expressed MPL, TCI assigns the highest probability to a member of PI3K/AKT pathway if it is altered in the same tumor. TCI identified PIK3CA as the most frequent cause for DEG of MPL (in 200 tumors), while PTEN is ranked the second most common cause (in 140 tumors). Interestingly, AKT1 and PIK3R1 are also among the top 10 most frequent causes of an MPL DEG (in 11 tumors and 10 tumors, respectively) (Fig 2B).

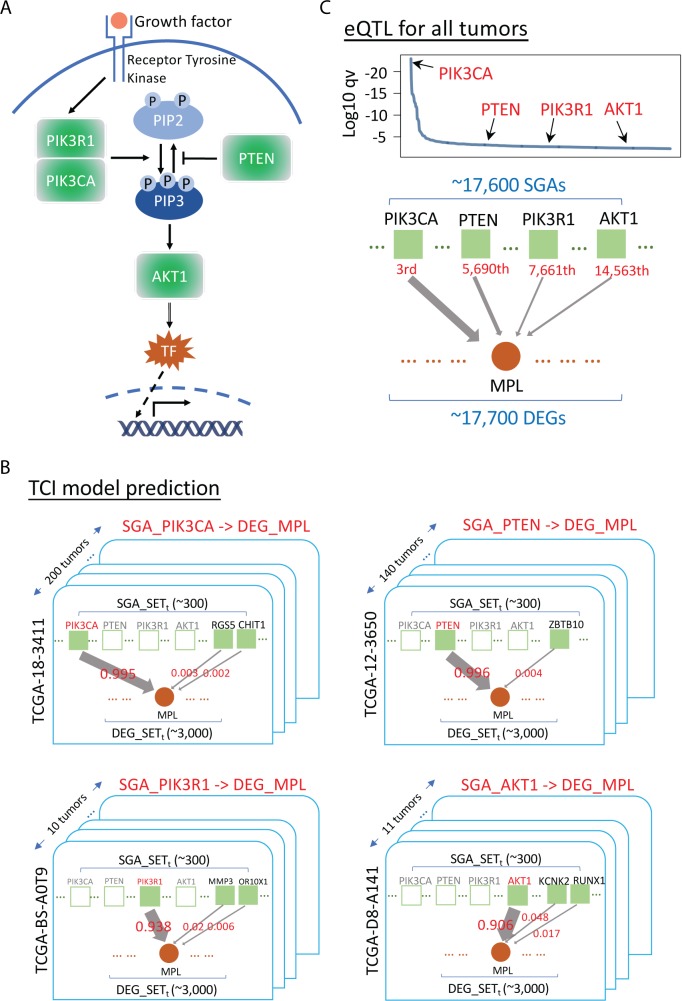

Fig 2. Estimation of the most probable causative SGAs for MPL by TCI and eQTL.

A. A diagram of PI3K/AKT pathway, with PIK3CA, PTEN, PIK3R1 and AKT1 as key signaling proteins in the pathway. B. Results of TCI analysis of the most probable causes of the DEG MPL. There are ~300 SGAs and ~3,000 DEGs in each tumor on average, which are organized as a bipartite graph respectively. Solid green squares represent SGAs present in the current tumor; empty green square represent SGAs not present in the current tumor. For a DEG observed in a tumor, e.g., MPL, TCI aims to search for the most probable cause among SGAs observed in the tumor. An arrow represents a causal link between an SGA and a DEG, while the weight of an arrow represents the posterior probability that the SGA causes the DEG in the current tumor. PIK3CA is predicted to be the most probable cause for DEG MPL in 200 tumors; thus, we rank PIK3CA as 1st. PTEN is the most probable cause for DEG MPL in 140 tumors, ranking it as the 2nd most probable cause of DEG MPL. AKT1 is the most probable cause for DEG MPL in 11 tumors, and PIK3R1 is the most probable cause for DEG MPL in 10 tumors. C. eQTL analysis of the possible causes of DEG MPL. eQTL considers all SGAs (i.e., ~17,600 SGAs) as possible causes for DEG MPL. The p values of PIK3CA, PTEN, PIK3R1 and AKT1 were ranked as having the 3rd, 5,690th, 7,661th and 14,563th strongest association with DEG MPL, respectively.

As a comparison, we also performed eQTL analyses [33, 34] to identify the SGAs that are associated with DEG events in MPL. eQTL assesses the strength of association of genomic variations on a quantitative trait (e.g., expression of a gene) at the population level, which is often used to study functional consequence of genomic variations. To perform eQTL analysis, we used the R package MatrixEQTL [42] which is a widely used tool specifically designed for ultra-fast eQTL analysis of large datasets (589 citations since 2012). It is also an official tool of the GTEx project (https://gtexportal.org/home/) and is used in the seeQTL browser (https://seeqtl.org/). We evaluated the association of all SGAs observed in TCGA with respect to expression change of MPL, and the p values for the association of four members of the PI3K/AKT pathway were ranked as 3rd (PIK3CA), 5,690th (PTEN), 7,661th (AKT1) and 14,563th (PIK3R1) among all other SGA events (Fig 2C) observed in the TCGA PANCAN cohort. For each tumor, we identified the SGA that had the strongest association with MPL DEG, according to the eQTL-derived p-values. The results showed that PIK3CA was ranked 1st, PTEN was ranked 113rd, PIK3R1 was ranked 128th, and AKT1 was ranked 165th as possible causes for MPL DEG in individual tumors. Thus, while eQTL analysis can identify PIK3CA as an important regulator of MPL expression, unlike TCI it does not attribute SGAs in other members of PI3K/AKT pathway as major causes for the changed expression of MPL at the population level.

TCI predicts the most probable tumor-specific causative SGA for each DEG

We defined an SGA event in a tumor as an SGA with functional impact (SGA-FI) if it was predicted by TCI to causally regulate 5 or more DEGs in the tumor with an expected false discovery rate ~ 10−7 for discovering SGA-FIs from randomized in silico experiments, which is determined based a series of random simulation experiments. (Methods and S1 Fig).

We identified a total of 634 genes that were called as SGA-FIs in more than 30 tumors with an SGA-FI call rate of 25% or greater in our pan-cancer analysis (Methods and S2 Table). The call rate for an SGA Ah is the ratio of number of tumors in which Ah is designated an SGA-FI over the number of tumors in which Ah occurs. These SGA-FIs include the majority of the previously published drivers [1, 2], as well as many novel candidate drivers. For 302 well known drivers from literature [1, 2], we found 93 were called as significant SGA-FIs and 262 were called as SGA-FIs in at least one tumor. Note that if SGAs in a well-known driver do not affect gene expression, e.g., mutation or deletion of BRCA1, TCI would not be able to detect its functional impact. In addition to protein-coding genes, TCI also identified SGA events affecting microRNAs and intergenic non-protein-coding RNAs (e.g., MIR31HG [43, 44], MIR30B [45], and PVT1 [46]) as SGA-FIs, (S2 Table).

We further identified target DEGs for the 634 significant SGA-FIs. To minimize false discovery, we required that a target DEG of an SGA-FI be regulated by the corresponding SGA-FI in at least 50 tumors or in 20% or more of all tumors in which the SGA was called as an SGA-FI. Since it is statistically difficult to evaluate whether the causal relationship between an SGA-FI and its predicted target DEG within an individual tumor is valid, we adopted a “pan-cancer” analysis approach to determine whether each predicted SGA→DEG causal relationship is conserved across tumors in different cancer types. We appreciate that there are cancer-type-specific effects, and we did applied the TCI algorithm to tumors of each tissue of origin or cell type to infer the causal relationships, although our presentation did not concentrate on such results. We addressed this issue in two major ways. First, when performing pan-cancer analysis, the goal is to identify the causal relationships that are shared among different cancer types, and conservation of causal relationships across different cancer types is a strong indication that the discovered causal relationship is more likely to be true. Therefore, we required that a causal edge is conserved in at least two types of cancers when TCI is applied to tissue-specific data. Second, since tissue-specific prevalence of certain SGAs and DEGs can create a confounding effect, in that they may appear to have correlations in a subset of tumors at the pan-cancer level. To mitigate such confounding effects, we specifically identified tissue-specific DEGs and removed them from pan-cancer analysis. We determine a DEG is a tissue-type-specific DEG if it exists in more than 90% of the tumors in one cancer type or tissue type while it appears in less than 1% of the tumors in other cancer types. We found and removed 44 such DEGs from further analysis (Materials and methods). We then set out to assess whether the inferred causal relationships are supported by existing knowledge and experimental studies. Finally, we performed preliminary laboratory experiments on selected SGA-FIs to evaluate the causal relationships between novel candidate drivers and their target DEGs predicted by TCI.

The landscape of causative SGAs identified by TCI

We compared the distribution of the number of SGAs and SGA-FIs per tumor across cancer types (Fig 3A and 3B). The average number of SGAs per tumor across cancer types was 268, whereas the average number of SGA-FIs identified by TCI was approximately 34 per tumor. Interestingly, TCI designated all SGAs with very high alteration frequency (perturbed in more than 500 tumors, or > 10%) as SGA-FIs (Fig 3C). One immediate concern for TCI is that it might call certain long genes, such as TTN and MUC16, as SGA-FIs solely due to their high genomic alteration rate. This concern was addressed by adopting statistical test results from MutSigCV analysis, which specifically addressed the biased mutation rate introduced by lengths and chromosome locations of genes. In our analysis, we represented the predicted effect of gene length and location by way of the prior probability term P(Ah→Ei), and as such, the prior probabilities for certain long genes, such as TTN and MUC16, were several orders of magnitude lower than other frequently altered well-known drivers (Fig 3D). Thus, the strength of statistical relationships between SGAs in these genes and their target DEGs, as conveyed by the marginal likelihood term P(D|Ah→Ei), must be sufficiently high to overcome the low prior probabilities of these genes being regulators of DEGs. Many SGA-FIs with an alteration frequency ranging from 30 to 500 tumors (0.5–10%) appear among other SGAs with similar protein lengths and alteration rates (Fig 3C). Since genes with similar protein length and alteration rate usually have similar prior probabilities of being drivers, TCI differentiated SGA-FIs from others based mainly on the difference in marginal probability P(D|Ah→Ei) associated with an SGA and candidate target DEGs. These results indicate that the function-oriented nature of TCI plays a significant role in detecting SGA-FIs.

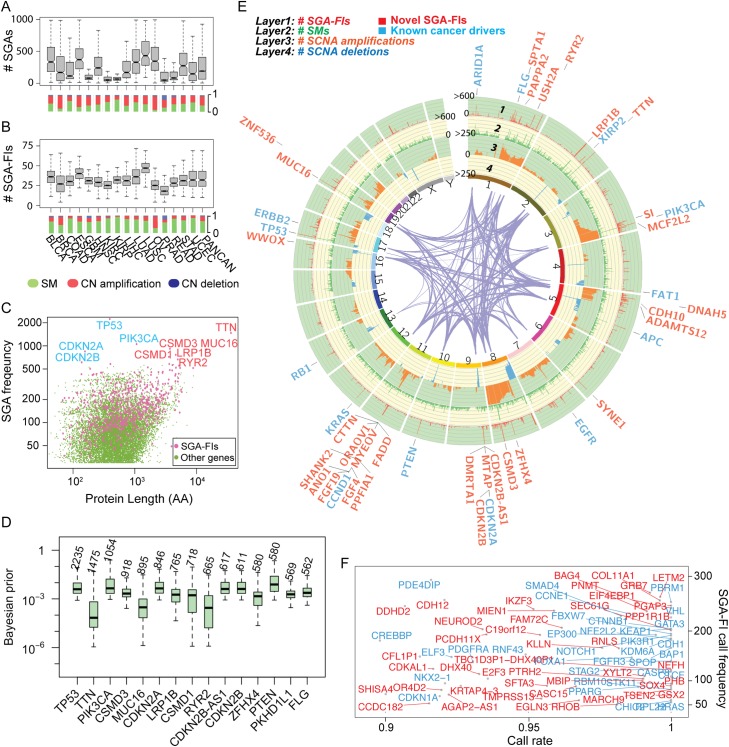

Fig 3. The landscape of SGAs and SGA-FIs.

A & B. The distributions of SGAs per tumor and SGA-FIs per tumor of different cancer types. Beneath the bar box plots, the distributions of different types of SGAs (SM, copy number amplification, and deletion) are shown. C. Distribution of SGA-FIs against the alteration frequency and protein length. Pink dots indicate SGA-FIs, and green dots represent SGAs that were not designated as SGA-FIs. A few commonly altered genes are indicated by their gene names, where genes labeled with blue font are well-known drivers, and those labeled with orange font are novel candidate driver. D. Tumor-specific Bayesian prior distributions for top 15 most frequent SGAs. The number above each box represents number of tumors that the corresponding SGA appears in. E. A Circos plot shows SGA events and SGA-FI calls along the chromosomes. Different types of SGA events (SM, copy number amplification, deletion) are shown in tracks 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Track 1 shows the number of times that an SGA is labeled by TCI as an SGA-FI. The gene names denote the top 62 SGA-FIs (some are SGA units) that were called in over 300 tumors with a call rate > 0.8. Genes labeled with blue font are known drivers from two TCGA reports, and orange ones are novel candidate drivers. F. SGA-FIs that were called in less than 300 tumors and with a call rate > 0.9 are shown in this frequency-vs-call rate plot. As before, genes labeled with blue font are known drivers from TCGA studies, and orange ones are novel candidate drivers.

We illustrated the landscape of common SGA events (Fig 3E) using a Circos plot (http://circos.ca/), and highlighted 44 SGA-FIs identified by TCI in more than 300 tumors (> 6% of the tumors) with a call rate (fraction of SGA instances affecting a gene being called as an SGA-FI event) greater than 0.8. The plot illustrates the integrative approach of TCI, which combines different types of SGA events in a gene and detects their function impact. For example, TCI combined mutation and deletion events in LRP1B (at 1 to 2 o’clock position on the plot) to detect common functional impact of these SGA events (see later section), whereas calling SGA-FI events for ERBB2 (Her2) is mostly associated with amplification of the gene. TCI also designated many relatively low-frequency SGAs as SGA-FIs (in ~ 30 tumors or ~ 0.5%) with high call rates (> 0.9) (Fig 3F). Of interest, besides identifying well-known cancer drivers, e.g., TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN, KRAS, and CDKN2A) as SGA-FIs, TCI also designated as SGA-FIs some very frequently altered genes, e.g., TTN, CSMD3, MUC16, LRP1B, and ZFHX4, whose roles in cancer development remain controversial. These genes are excluded from driver gene lists when assessed by mutation-centered and frequency-based methods [2, 16], but other computational and experimental studies [47–49] suggest that some of them are likely cancer drivers.

Combining SM and SCNA enhances detection of the functional impact of genes affected by SGAs

A cancer driver gene is often perturbed by multiple types of SGA events that exert common functional impact. For example, an oncogene, such as PIK3CA, is usually affected by activating mutations or copy number amplifications, whereas a tumor suppressor, such PTEN, is usually affected by inactivating mutations or copy number deletions. An SCNA event (amplification or deletion of a chromosome fragment) in a tumor often encloses many genes, making it a challenge to distinguish the functional impact of genes within a SCNA fragment.

TCI addresses this problem by integrating both SM and SCNA data, which can create variances in overall SGA events among genes within a SCNA fragment. When combined with SM data, PIK3CA clearly has a higher combined alteration rate than its neighbor genes in the same DNA region with very similar amplification rate in cytoband 3q26. While its neighbor genes share almost identical copy number amplification profile across all tumors, the alteration profile of PIK3CA is significantly different when both SM and SCNA data are considered (Fig 4A). When calculating whether amplification of PIK3CA is causally responsible for a DEG observed in a tumor, TCI uses the statistics collected from all tumors with PIK3CA alterations, including both CN amplification and SM, to compute the marginal likelihood and predict whether a causal relationship between PIK3CA amplification and the DEG exists in the tumor. As such, the algorithm is able to differentiate the functional impact of PIK3CA amplification from that of other co-amplified genes. We noted that many genes were affected by both SMs and SCNAs patterns, including CSMD3 and ZFHX4 (Fig 4A), enabling TCI to detect the functional impact of these SCNA events.

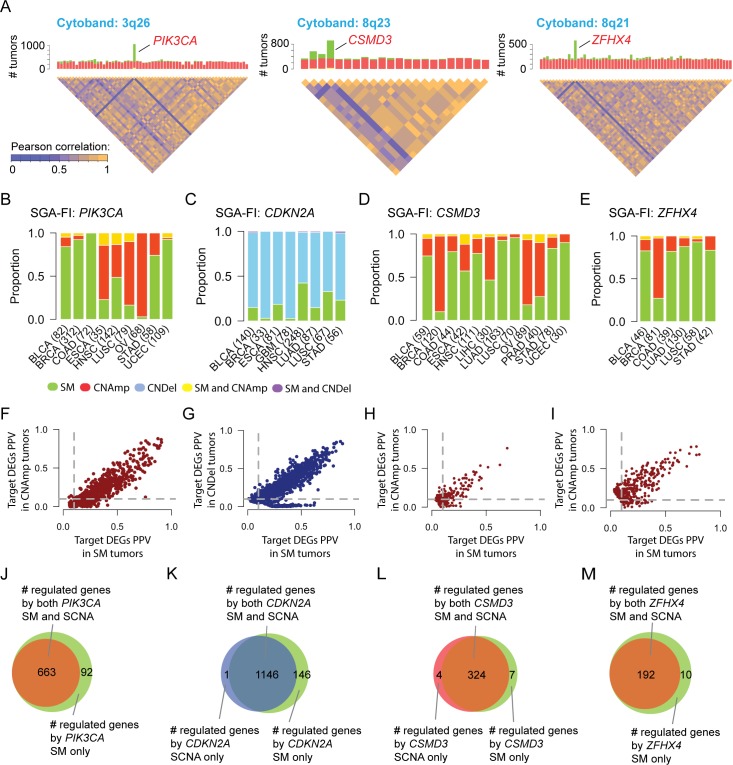

Fig 4. SM and SCNA perturbing a gene exert common functional impact.

A. Combining SM and SCNA data drisrupts the correlation structure among genes enclosed in common SCNA fragments. The chromosome cytobands enclosing three example genes (PIK3CA, CSMD3, and ZFHX4) are shown. The bar charts show the frequency of SCNA (red, standing for amplificaton) and SM (green). The disequilibrium plots beneath the bar charts depict the correlationship among genes within a cytoband. B-E. The SGA patterns, i.e. SM and CN amplification/deletion, across different cancer types for PIK3CA, CDKN2A, CSMD3 and ZFHX4, F-I. SGA-FI target DEG call rates in SM tumors and CN amplification/deletion for PIK3CA, CDKN2A, CSMD3 and ZFHX4. J-M. Venn diagrams illustring the relationships of DEGs caused by CN amplication/deletion and SM for PIK3CA, CDKN2A, CSMD3 and ZFHX4.

By combining both SM and SCNA data, TCI is able to identify common functional impact of distinct types of SGA events affecting the same gene across different tumors and cancer types. For example, PIK3CA is often perturbed by either SMs or CN amplifications (Fig 4B) although prevalence of each type is different in different cancer types. In breast cancers (BRCA), PIK3CA is commonly altered by SMs; in ovarian cancers (OV), it is more often affected by CN amplification; in head and neck squamous carcinoma (HNSC), it is almost equally altered by SMs and CN amplification. As a well-known cancer driver in many cancer types, it is expected that amplification and mutations of PIK3CA should share a common functional impact in causally regulating a common set of DEGs.

Taking advantage of the tumor-specific inference capability of TCI analysis, we identified the target DEGs regulated by each SGA event affecting PIK3CA (either SM or SCNA) in individual tumors. DEGs predicted to be caused by either PIK3CA SM or CN amplification have very similar positive predictive values (PPV) with respect to SGA events in PIK3CA. The PPV is calculated as the ratio of number of tumors in which a DEG is designated as target of an SGA-FI such as PIK3CA over all tumors in which PIK3CA is called as an SGA-FI (Fig 4F and Methods), which reflect the strength of causal relationships between an SGA and its target DEG. The results indicate that perturbation of PIK3CA by both SM and CN amplification have very similar functional impact on gene expression changes. We then examined whether target DEGs caused by PIK3CA SM overlap with those caused by CN amplification, and indeed the DEG members of the two list significantly overlapped (Fig 4J). Thus, TCI detected the shared functional impact of distinct types of SGAs perturbing PIK3CA across different cancer types. Similar results were obtained for other 249 SGA-FIs (S3 Table) that were commonly perturbed by both SMs and SCNAs (with each type accounting for > 20% of instances for each SGA-FI), including CDKN2A, CSMD3 and ZFHX4 (Fig 4).

Causal relationships inferred by TCI are statistically robust

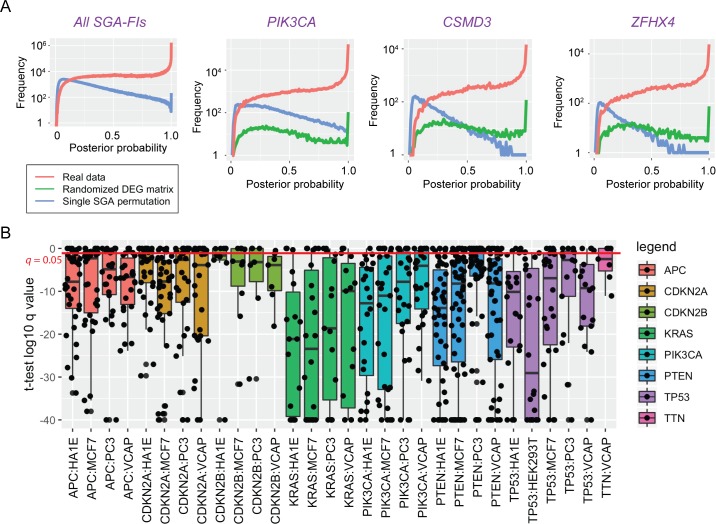

To evaluate validity of the results by TCI, we first examined whether the causal relationships reported by TCI reflect true statistical relationships between SGA and DEG events rather than random noise in the data. We generated a series of random datasets using the TCGA data, in which the DEG status of each gene expression variable was permuted among the tumors, while the SGA status in each tumor remained as reported by TCGA. After permutation, the statistical relationships between SGAs and DEGs are expected to be random. We then applied TCI to these random datasets and compared the posterior probabilities of the most probable causal edges for each DEG derived using real and permuted data. The results (Fig 5A) show TCI was able to differentiate true statistical relationships between SGAs and DEGs from random ones in that it assigned higher posterior probabilities to candidate edges obtained from real data (red lines) than those obtained from random data (blue lines). As expected, a large number of derived causal edges from well-known cancer drivers (e.g., TP53 and PIK3CA) were assigned high posterior probabilities. Interestingly, the results also show many causal edges from other common SGA-FIs (TTN, CSMD3, MUC16, and ZFHX4) to DEGs were also assigned higher posterior probabilities than would be expected by random chance, indicating that perturbing these genes had significant impact on transcriptomics of the tumors (Fig 5A and S2A Fig). The function-oriented nature of TCI is reflected by observations that there are certain SGAs with a high alteration frequency (occurring in close to 10% of tumors) that were not designated as SGA-FIs by TCI. For example, WASHC5 has SGA events in 457 tumors but few of these SGA events were assigned with high posterior probabilities of being SGA-FIs by TCI; similar results were observed for TBC1D31 (424 tumors) and ADGRB1 (420 tumors) (S2B Fig).

Fig 5. Statistical and experimental evaluation of TCI predictions.

A. The causal relationship inferred by TCI is statistically sound. Plots in this panel show the probability density distribution of the highest posterior probabilities assigned to each DEG in TCGA dataset, when the TCI algorithms was applied to real data (red) and two random datasets, in which DEGs permutated across all tumors (blue) and the corresponding SGA permutated across all tumors (green). The panel on the left shows the results for the posterior probabilities for all most probable candidate edges in whole dataset; rest of the plots show the distributions of posterior probaiblities of most probable edges pointing from 3 specific SGAs to predicted target DEGs. B. Boxplots of q-values of t-test associated with predicted target DEGs for 8 SGA-FIs in different LINCS cell lines that were experimentally perturbed. Each box represent one SGA perturbed in one cell line. For example, APC-HA1E denotes that APC perturbed in HA1E cell line. Each black dot represents a q-value associated with a target DEG of an SGA-FI, when the expression value was assessed with a t-test of the before and after genetic manipulation of a given SGA-FI gene.

To further exclude the possibility that TCI-reported causal relationships from a high-frequency SGA to DEGs were random associations due to their high alteration frequencies, we conducted another series of single-SGA-permutation experiments, in which the SGA events of a gene (e.g., TTN) were randomly permuted across all tumors to disrupt the statistical relationships between SGAs of this gene and DEGs, while the overall frequency of the SGAs of the gene remains the same. We performed such single-SGA-permutation experiments for the 6 most commonly altered genes: TP53, TTN, PIK3CA, CSMD3, MUC16, and ZFHX4. The results (Fig 5A and S2B Fig) also show that when TCI analysis was applied to these permuted data (green lines), none of these 6 genes were designated as an SGA-FI according to our criteria. Taken together, these results support that TCI is detecting valid (non-spurious) statistical relationships between SGA and DEG events in real data.

Causal relationships inferred by TCI are biologically sensible

We further evaluated whether the TCI-inferred causal relationships between SGAs and DEGs agree with existing knowledge and experimental results. We compared the predicted causal relationships between PIK3CA and DEGs with experimental results from an independent study. Recently, Hart et al. [50] studied the functional impact of a single mutation, H1047R, of PIK3CA by knocking in the mutation into the breast epithelial cell line MCF-10A and comparing the transcriptomic profile between the wild type and the PIK3CAH1047R isogenic cell lines, which is the only transcriptomic study that is associated with the PIK3CA hotspot mutation so far. They identified 1,434 DEGs caused by the introduction of the mutation. We note that there exist differences among different cell lines and also between cell lines and tumor samples. In order to bridge the gap between cell lines and Pan-cancer tumor samples, we extracted the BRCA samples and compared the TCI-predicted PIK3CA target DEGs in breast cancer tumors with that from Hart’s study. We found that 12 out of 92 TCI-predicted PIK3CA SM driving DEGs overlap with the experimentally-derived DEG set (hypergeometric test p = 0.01).

Since RB1 protein regulates the function of transcription factor E2F1[51], it is expected that E2F1-regulated genes should be enriched among the RB1-targeted DEGs predicted by TCI. We used the PASTAA program[52] (trap.molgen.mpg.de/PASTAA.htm) to search for motif binding sites in the promoters of the 237 DEGs that TCI predicted to be regulated by RB1, and it found that E2F1, E2F2, and DP-1 were the three top transcription factors for these genes (p < 10−6).

We also used the large-scale perturbation experiments carried by the Library of Integrated Network-Based Cellular Signatures (LINCS) project [53] to evaluate predicted causal relationships between SGA-FIs and their predicted target DEGs. The LINCS project performed systematic gene-manipulation (knockdown and overexpression) experiments using small interfering RNAs targeting over 4,000 genes in multiple cell lines, and cellular responses were measured as expression changes in 978 landmark genes (using a technology referred to as the L1000 assay). We selected the 8 most frequent SGA-FIs that were also experimentally manipulated in the LINCS project and performed t-tests on the expression values of all L1000 genes and analyzed the results of the perturbation experiments relative to the control condition in each cell line. We then examined the statistical significance of these differences and assessed the false discovery rate (q values) associated with the predicted target DEGs of each SGA. For each of the 8 SGA-FIs, the majority of predicted target DEGs were differentially expressed in multiple cell lines after experimental manipulation of the SGA-FI genes (Fig 5B). We note that certain target DEGs of an SGA have tissue-specific expression patterns, and we organized targeted DEGs according to tissue of origins and examined the percent of DEGs responding to manipulation of corresponding SGAs (S4 Table). Interestingly, we also found that TTN was perturbed in one cell line (VCAP), and 5 out of 7 predicted target DEGs responded to manipulation of TTN. Among them, 4 genes (SPP1, STAT1, C5 and GPER1) are known to be associated with development and/or progression of cancer [54–57]. In summary, the causal relationships between SGAs and DEGs predicted by TCI were supported by multiple lines of examination, including the use of existing knowledge of these relationships as well as targeted and systematic experimental results.

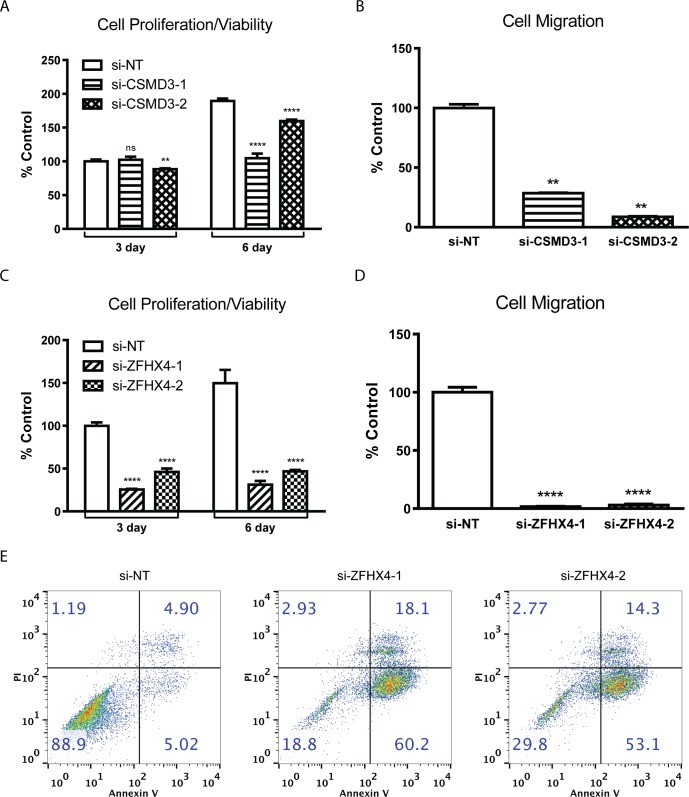

TCI indicated that CSMD3 and ZFHX4 are 4th and 12th most frequent SGA-FIs, and yet, they are designated as cancer drivers (S2 Table) in previous studies [17–22]. We examined whether experimental manipulations of CSMD3 and ZFHX4 expression affect oncogenic phenotypes. We identified two cancer cell lines, HGC27 and PC3, with CSMD3 and ZFHX4 amplification respectively, and we knocked down the expression of the two genes using siRNAs, followed by monitoring cellular phenotypes (see Methods for details). Our results showed that knocking down CSMD3 and ZFHX4 in the respective cell lines significantly attenuated cell proliferation (viability) and migration (Fig 6A–6D). In addition, knockdown of ZFHX4 induced apoptosis (Fig 6E). These results provide support that these genes are involved in maintaining the cancer-related cellular phenotypes in these cell lines.

Fig 6. Cell biology evaluation of oncogenic properties of CSMD3 and ZHFX4.

A-B. The impact of knocking down CSMD3 and ZFHX4 on cell proliferation. C-D. The impact of knocking down CSMD3 and ZFHX4 on cell migration. E. Impact of ZFHX4 knockdown on apoptosis in PC3 cell line measured by Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining.

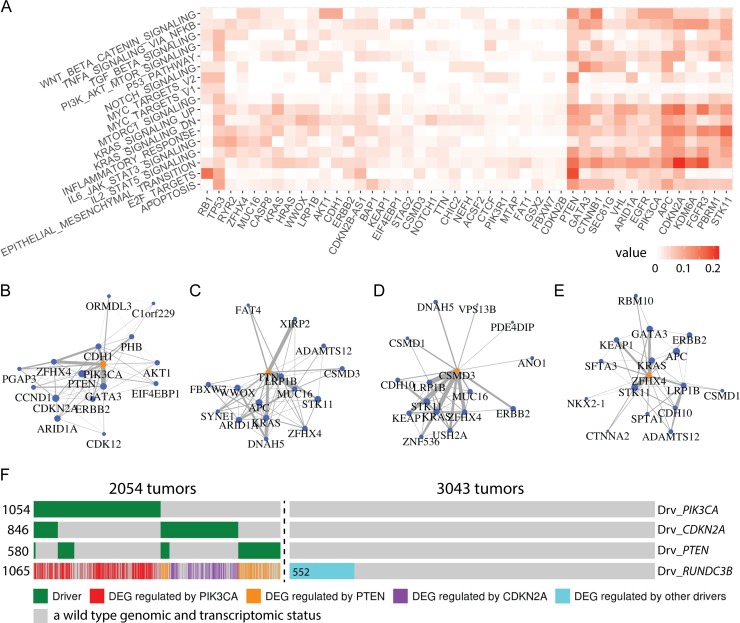

SGA-FIs regulate genes involved in well-known oncogenic processes

To gain a better view of functional impacts of SGA-FIs in cancer development, we further examined their impact on 1,855 genes from 17 cancer-related “hallmark” gene sets from the MSigDB (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp). On average, 374 cancer hallmark genes are found to be differentially expressed in a tumor. TCI found 96 SGA-FIs that are predicted to regulate members of these 1,855 hallmark genes. These results illustrate the impact of an SGA on cancer hallmark processes. We listed the relationships between the 96 SGA-FIs with respect to the 17 cancer hallmark processes to identify the target DEGs for each of 96 SGA-FIs (S5 Table). The relationships between top 45 SGA-FIs with largest number of target DEGs with respect to the hallmark processes are shown in (Fig 7A). For example, CTNNB1 is known as the top regulator of WNT pathway and it is predicted by TCI to cause 14% DEGs in HALLMARK_WNT_BETA_CATENIN_SIGNALING pathway [58]; RB1 regulates 15% of the genes in HALLMARK_E2F_TARGETS [59]; TP53 regulates genes involved in apoptosis and in a broad assortment of functions across many other oncogenic pathways [60, 61]; Our analysis also suggests that CDKN2A plays an important role in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process, which agrees with previous studies [62].

Fig 7. Detection of functional impact of SGA-FIs reveals functional connections among SGA-FIs.

A. Top 45 SGAs-FIs (regulating the largest number of DEGs) and their relationships with 17 cancer hallmark gene sets. The value in a cell represents the fraction of genes in a hallmark gene set that is covered by the target DEGs of each SGA-FI. B-E. Top 15 SGA-FIs that share the most significant overlapping target DEGswith PIK3CA, TTN, CSMD3, and ZFHX4. An edge between a pair of SGA-FI indicate that they share significantly overlapping target DEG sets, and the thickness of the line is proportional to negative log of the p-values of overlapping target DEG sets. F. An “oncoprint” illustrating the causal relationships between the DEG RUNDC3B and its 3 main drivers according to TCI, namely, PIK3CA, CDKN2A, and PTEN. Each column corresponds to a tumor; green bars indicate tumors in which TCI designated each of the three SGA genes as a driver, regardless of what DEGs it was driving in a given tumor. The causal relationship is color-coded, which illustrates which SGA-FI is predicted by TCI to cause the RUNDC3B DEG event; the blue bar indicates the DEG events that were assigned to SGA-FIs other than the above 3 SGA-FIs; gray bars indicate a wild type genomic and transcriptomic status.

TCI analyses reveal functional connections among SGA-FIs

The causal relationships between SGAs and DEGs revealed by TCI enable us to explore whether distinct SGAs in different tumors do in fact perturb a common signal, by examining if they share overlapping target DEGs. To this end, we evaluated all pair-wise intersections between target DEG sets of SGA-FIs to identify SGA pairs sharing significantly overlapping target DEGs (p < 0.05 Fisher’s exact test, and q < 0.05), and found 2669 such SGA-FI pairs (S6 Table). We then organized SGA-FIs that perturb common signals into a graph, in which an edge connecting a pair of SGA-FI nodes indicates significant overlap of their target DEGs. For example, the top 15 SGA-FIs (ranked according to the FDR p values of overlapping DEG sets) that share DEGs with PIK3CA include PTEN, CDH1, ERBB2, and GATA3, which are known cancer drivers, and their connections agree with existing knowledge (Fig 7B) [63–65].

The capability of revealing functional connections among SGAs provides a means of evaluating whether a novel candidate driver shares functional impact with well-known drivers, which not only provides an indication of whether the candidate driver is involved in oncogenic processes (and thus a candidate cancer driver gene) but also sheds light on which pathway it may be involved in. The top 15 SGA-FIs sharing common target DEGs with TTN include some well-known drivers including APC, KRAS, and STK11 (Fig 7C). Therefore, TTN may share similar functional impact with these known drivers. The top 15 SGA-FIs connected with CSMD3 and ZFHX4 (Fig 7D and Fig 7E) also form densely connected networks that include well-known cancer drivers, such as KRAS, GATA3, KEAP1, ERBB2 and STK11, suggesting that alteration of CSMD3 and ZFHX4 may perturb some of the same signaling pathways as do these known drivers. We found similar results for other common SGA-FIs, including CDKN2A, PTEN, MUC16, and LRP1B (S3 Fig).

Transcription of a gene is often regulated by a pathway, and it is expected that major driver SGAs of a DEG should include members of such a regulatory pathway. As an example, Fig 7F shows the SGA events that TCI designated as the cause of differential expression of RUNDC3B in different tumors. The TCI analysis indicates that PIK3CA is the most common cause. Besides SGAs in PIK3CA, TCI inferred that SGAs in CDKN2A and PTEN are two other major drivers of RUNDC3B DEG events. The results suggest that aberrations in PI3K pathway (as a result of SGAs perturbing PIK3CA and PTEN) is the main cause of these DEG events, and CDKN2A may act as an alternative regulator. It is also interesting to note that in certain tumors when both SGAs affecting CDKN2A and PTEN were present, TCI assigned PTEN as the most likely driver of RUNDC3B, instead of CDKN2A, even though the SGAs in the latter are more frequent. The results indicate that although CDKN2A SGA events explain the overall DEG variance of RUNDC3B better than PTEN, the strength of statistical association between PTEN and some DEGs in certain tumors may be stronger than that of CDKN2A, and TCI can detect such statistical relationships.

Tumor-specific causal inference reveals tumor-specific disease mechanisms

TCI analysis enables us to identify major SGAs that causally regulate molecular phenotypic changes (in the current case, DEGs) in an individual tumor. In this way, TCI not only discovers potential drivers of an individual tumor but also suggests which oncogenic processes they may affect. Thus, TCI can provide insights about tumor-specific disease mechanisms, particularly when more oncogenic phenotypic data types become available, such metabolomic data and protein expression data.

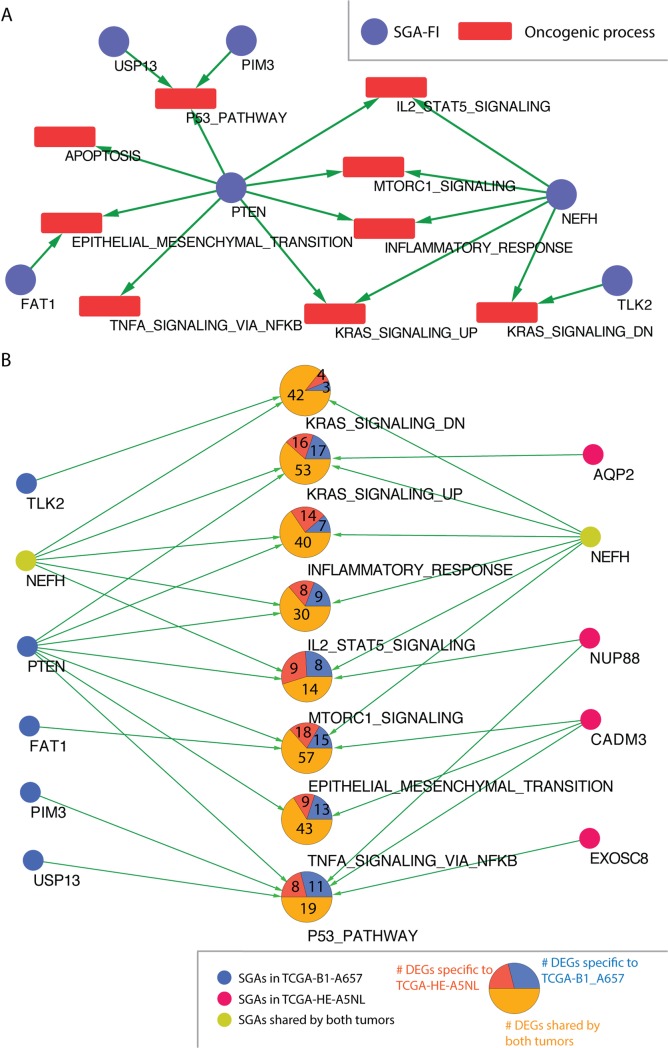

TCI results enabled us to examine each tumor profiled by TCGA to identify the major candidate driver SGAs and their target DEGs. Further examining the DEGs involved in hallmark biological processes allows us to study which biological processes an SGA affects. As an example, Fig 8A shows the SGA-FIs and their target cancer processes for a tumor (TCGA-B1-A657) of Kidney Renal Papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP), where genes in 9 oncogenic hallmark process from MSigDB are significantly enriched among the DEGs, including the following pathways that are strongly regulated by one of more SGA-FIs: the Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition pathway, the KRAS signaling pathway, the TNFA signaling via NFKB pathway, and the IL2 STAT5 signaling. We also identified major SGA-FIs (according to the number of DEGs regulated by them in the tumor) that affect these processes (Fig 8A). In this figure, a green arrow indicates that an SGA-FI regulates at least 10% of the genes in the corresponding signaling pathway. TCI identified 6 such SGA-FIs, including some well-known cancer drivers, such as PTEN and NEFH, and potential cancer drivers mentioned in recent studies, such as TLK2[66], USP13[67], and PIM3[68].

Fig 8. TCI predicts the SGA-FIs and their functional impact at the individual tumor level.

A. A graph produced by TCI for tumor TCGA-B1-A657 that predicts major SGA-FIs and their regulated cancer processes. Blue nodes represent SGA-FIs and red nodes (squares) represent oncogenic processes. An green directed link indicates that TCI predicts that the SGA-FI at the tail of tha arrow regulates 10% or more of the DEGs in the cancer process at the head of the arrow. B. Same DEGs regulated by distinct SGA-FIs in different tumors. DEGs in cancer processes shared between tumor TCGA-B1-A657 and tumor TCGA- HE-A5NL are shown as pie-charts. Blue nodes denote SGA-FIs in tumor TCGA-B1-A657. Red nodes denote SGA-FIs in tumor TCGA- HE-A5NL. Yellow nodes, (i.e., NEFH), are shared by both tumors. Each large node in the middle represents an oncogenic process. Within the circular nodes in the middle of the figure, the number in the purple area denotes the number of DEGs specific to TCGA-B1-A657. The number in the red area denotes the number of DEGs specific to TCGA- HE-A5NL. The number in the yellow area denotes the number of DEGs shared by both tumors. An green directed link indicates an SGA-FI regulates 10% or more DEGs in the cancer process.

SGAs cause cancer by perturbing cellular signaling pathways, and a pathway usually consists of multiple signaling proteins. Thus, it is possible that tumors having very distinct SGA profiles may in fact share very similar patterns of pathway perturbation, thus sharing similar gene expression profiles. We further identified another KIRP tumor (TCGA-HE-A5NL), which shares a similar overall DEG profile to that of TCGA-B1-A657 (Fig 8B). These two tumors shared 281 DEGs related to the aforementioned oncogenic processes, and many DEGs in each oncogenic process were shared by the two tumors. However, each of these two tumors also had its unique SGA set, such as 57 SGAs in TCGA-B1-A657, 65 in TCGA-HE-A5NL, and only 2 common SGAs (CADM3 and NEFH). TCI discovered similar target DEGs for NEFH in both tumors. Although many DEG members in each oncogenic process were shared, different SGA-FIs were designated as their candidate drivers. The above results illustrate that TCI is able to suggest disease mechanisms of individual tumors, and such information can be further analyzed to suggest tumors sharing common disease mechanisms.

Discussion

TCI is novel computational framework to assess whether a genomic alteration event causally influences one or more molecular/cellular phenotypes at the level of individual tumor. This tumor-specific and causality-center framework provides a new perspective to study cancer driver genes and disease mechanisms of individual tumors. The tumor-specific nature of TCI enables discovering causal relationships and shedding light on disease mechanism of an individual tumor. Further exploring the commonality and differences in disease mechanisms of a large number of tumors in the population will significantly help us better understand cancer biology in general. More importantly, understanding the disease mechanism of each tumor lays a solid foundation for guiding personalized therapies and advancing precision oncology. The causality-centered nature of the TCI provides a unifying framework to combining data (statistics) of different types of SGAs, eliminating the need of separately assessing whether mutations, or SCNAs, or other SGA events in a gene are over-enriched in a cancer population by conventional approaches, which would require reconciling measurements and baseline models associated with each type of SGA. Integrating diverse types of SGA events is statistically sensible which increases the statistical power for assessing the functional impact of perturbing a candidate driver gene. It is also biologically sensible that a driver gene is often perturbed by different types of SGA events leading to common functional impact. The fact that a gene is often perturbed by different types of SGAs leading to common phenotypic changes provides strong support that the gene is a candidate driver because its functional impact is positively selected in cancer.

Our analyses of TCGA data revealed the functional impact of many well-known, as well as a large number of novel SGA-FIs, with a wide range of prevalence in tumors ranging from 1% to more than 10%. These results serve as a catalogue of major SGA events that potentially contribute to cancer development. Discovery of novel candidate drivers also provides potential targets for developing new anti-cancer drugs. By revealing the functional impact of candidate drivers (e.g., a signature of DEGs), TCI results can be utilized to identify SGAs sharing similar functional impact and to discover cancer pathways de novo or to map novel candidate drivers to known pathways.

Interestingly, TCI revealed functional impact of certain SGAs with very high alteration frequencies, such as TTN, CSMD3, MUC16, RYR2, LRP1B, and ZFHX4, whose roles in cancer development remain controversial. There are studies indicating that their high mutation rates are likely due to heterogeneous mutation rates at different chromosome locations [2, 16]. TCI analysis provides a new perspective to examine the role of these genes: assessing whether perturbations (considering all SGA events) in these genes are supported as causally influencing molecular and cellular phenotype changes. Instead of concentrating on assessing whether its frequency is above random chance, TCI evaluates the functional impact of an altered gene that determines whether it contributes to (drives) cancer development. Our results suggest that perturbing these genes, either by genome alterations, such as SM and/or SCNA, or by experimental manipulations, has significant impact on molecular and cellular changes in both tumors and cell lines. Therefore, these results motivate further investigation of an alternative hypothesis for high overall alteration rates of these genes in cancer: perturbation of these genes leads in a variety of ways to functional changes that provide oncogenic advantages. The results suggest that utilizing diverse types of SGA events in these genes is in fact a result of positive selection.

The TCI model can be extended in several ways. First, with its capability of integrating heterogeneous data types, TCI can be further extended to include additional SGA types (e.g., DNA methylation) and molecular phenotypes (e.g., protein expression and metabolomics data) in order to provide a more comprehensive model of the causal relationships within tumor cells. Such extensions can be readily achieved by representing such events in the SGA data matrix, with minimum change in the TCI algorithm. Second, the functional impact of each SGA (i.e., either activating or repressing the gene expression) should be further studied to determine the SGA-FI as an oncogene or a tumor suppressor. Third, the TCI search algorithm can be relaxed to allow synergistic interactions between SGAs in regulating a single DEG which can be crucial to induce complex changes in gene expression pattern [69]. Last but not the least, the recent emergence of single cell multi-omics sequencing technology has enabled researchers to analyze gene mutations, copy number variants, methylations and gene expression changes simultaneously at the individual cell level [70–72]. When large, multi-omics, tumor single-cell cohort datasets become available, they will provide us the opportunity to perform TCI on tumor multi-omics data at the single cell level and advance our understanding of cell-to-cell variability and thus cancer progression.

Conclusion

This paper presented the TCI algorithm, which concentrates on addressing a fundamental question in discovering cancer-driving genes: whether perturbation of a gene (considering different types of perturbations) is causally responsible for certain molecular/cellular phenotypes (considering different phenotypic measurements) relevant to cancer development in a tumor. We combined multiple heterogeneous genome data types and applied the TCI algorithm to 5,097 tumors across 16 cancer types from TCGA. TCI identified over 600 significant SGA-FIs, including many known drivers, which were further supported by our computational analysis and experimental evaluations. We illustrated that these SGA-FIs regulated expression changes of genes involved in well-known oncogenic processes. We showed that two tumor samples with very similar DEG expression profiles may nonetheless have significantly different SGA-FIs that account for those profiles. Thus, TCI provides a new statistical framework for predicting causal SGAs and understanding their functional impact on oncogenic processes of an individual tumor. Finally, TCI is a special case of a general instance-based causal inference framework [73, 74] that can be broadly used to delineate causal relationships between genomic variance and phenotype changes at the level of individuals which can be a single cell or an individual patient.

Materials and methods

SGA data collection and preprocessing

We obtained SM data for 16 cancer types directly from the TCGA portal (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/dataAccessMatrix.htm) (accessed in October 2014). We considered all the non-synonymous mutation events of all genes and considered the mutation events at the gene level, where a mutated gene is defined as one that contains one or more non-synonymous mutations or indels.

SCNA data were obtained from the Firehose browser of the Broad Institute (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/). TCGA network employed GISTIC 2.0[25] to process SCNA data, which discretized the gene SCNA into 5 different levels: homozygous deletion, single copy deletion, diploid normal copy, low copy number amplification, and high copy number amplification. We only included genes with homozygous deletion or high copy number amplification for further analysis. We further screened out the genes with inconsistent copy number alteration across tumors in a given cancer type (i.e., gene was perturbed by both copy number amplification and deletion events in the same cancer type and both types of events occurred > 25% of tumors).

We combined preprocessed SM data and SCNA data as SGA data, such that a gene in a given tumor was designated as altered if it was affected by either an SM event and/or an SCNA event.

DEG data collection and preprocessing

Gene expression data were preprocessed and obtained from the Firehose browser of the Broad Institute. We used RNASeqV2 for cancer types with expression measurements in normal tissues. For cancer types without RNASeqV2 measurements in normal cells (i.e., glioblastoma multiforme and ovarian cancer), we used microarray data to identify DEGs. We determined whether a gene is differentially expressed by comparing the gene expression in the tumor cell against that in the corresponding tissue-specific normal cells. For a given cancer type, assuming the expression of each gene (log 2 based) follows Gaussian distribution in normal cells, we calculated the p values of each gene in a tumor, which estimated how significantly different the gene expression in tumor was from that in normal cells. If the p value was equal or smaller than 0.005 to either side, the gene was considered as differentially expressed in the corresponding tumor. Furthermore, if a DEG was associated with the SCNA event affecting it, we removed it from the DEG list of the tumor. We also removed tissue-specific DEGs if they were highly correlated with cancer types or tissue origin (i.e., Pearson correlation coefficient larger than 0.9). We thus identified the DEGs for each tumor and created a tumor-gene binary matrix where 1 represents expression change, and 0 represents no expression change.

Tumor-specific model priors

Defining an informative prior that can represent the biological foundations of different genome alterations in tumor cells can help us effectively correct model bias and thus make accurate predictions [30, 75]. Therefore, we need to specify the model prior P(Ah→Ei) for each SGA Ah in each tumor t by comparing its alteration frequency in the tumor cohort against normal cells. In our paper, we used additional genomic information for both SM and SCNA to derive the prior probability of each edge Ah→Ei using existing prior knowledge. We calculated and collected the following SGA information for each gene h: (1) the MutSigCV p value for h among the tumors in D from TCGA, and (2) the copy number amplification and deletion of h in a normal population without cancer from 1000 genome project (http://www.internationalgenome.org/) [76, 77]. Such information can be applied to help account for mutation and copy number alterations that are due to differences in gene lengths and chromosome locations which doesn’t depend on SGA frequency.

For a tumor t and an arbitrary DEG Ei, we defined the prior probability of Ah being a parent of Ei using a multinomial distribution with a parameter vector θ = (θ0,θ1,θ2,…,θh,…,θm)T, where . Here, θ0 is a user-defined parameter representing the prior belief that the non-SGA factor A0 being the cause of Ei, and θh represents the prior probability of Ah being the cause of Ei. In this study, we set θ0 = 0.1. We assumed that θt~Dir(θt|μt), where is a tumor-specific Dirichlet parameter vector governing the distribution of θt. For a tumor t, we calculated the prior probability θh as follows:

| (3) |

where h’ indexes over the m variables in SGA_SETt; ph is MutSigCV p value for Ah and μh = 1−ph is a Dirichlet parameter.

We also analyzed three different ways of calculating θh. First, as a simple default, we assume there are no informative priors. We distribute the residual probability mass evenly for all SGAs in tumor t as . Second, we infer informative priors by incorporating SGA frequency as , where fh is the alteration frequency of SGA h. The idea is that the driver genes should be positively selected to drive cancer progression, and therefore more likely are enriched in the tumor population. Third, we consider both SGA frequency and number of SGAs in each tumor so that the prior is calculated as , where , mt is the number of SGAs in tumor t and Uh denotes the tumor set in which SGA h has a genome alteration.

Different ways of calculating priors correspond to different biological assumptions, and thus, have distinct values, as shown in S7 Table. However, as illustrated in S8 and S9 Tables, a significant portion of the SGA regulators for DEGs and SGA-FIs called in each tumor remain the same for different priors. Thus, the strength of statistical relationships between SGAs and their target DEGs, as influenced by the marginal likelihood term P(D|Ah→Ei), are sufficiently high to overcome the differences in prior probabilities of some SGAs being regulators of DEGs even if the priors are calculated differently.

Sensitivity analysis of A0 prior effect

We performed sensitivity analysis to examine the effect of the A0 prior. We used TCI to predict the SGA regulators for DEGs in each tumor using different A0 priors, i.e., 0.001, 0.005, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5. We compared the top SGA changes for DEGs in each tumor. As shown in S4 Fig, the top SGA changes are not significant, i.e. <0.08%, even though there is a 500-fold change for the A0 priors. We found TDI results are quite stable when the A0 prior is in the range of 0.05 to 0.3. We then set 0.1 as the prior probability for A0.

Identification of SGA-FIs

Causal edges from different SGAs have different posterior probabilities, as expected. To standardize how to interpret the significance of a posterior probability for a causal edge Pe, we designed a statistical test based random permutation experiments. We generated a series of permuted datasets using the TCGA data, in which the DEG values were permuted among the tumors of a common tissue of origin, while the SGA status in each tumor remained as reported by TCGA. This permutation operation disrupts the statistical relationships between SGAs and DEGs while retaining the tissue-specific patterns of SGAs and DEGs. We applied TCI algorithm to permuted data to calculate posterior probabilities of edges emitting from each SGA in random data. We then determined the probability that an edge from an SGA could be assigned with a given Pe or higher in data from permutation experiments (i.e., the p value to the edge with a given Pe).

The p value in this setting is also the expected rate of false discovery of an SGA as the cause of a DEG by random chance. We utilize this property to control the false discovery rate when identifying SGA-FIs in a tumor. We designated an SGA event in a tumor as an SGA-FI if it has 5 or more causal edges to DEGs that are each assigned a p-value < 0.05. The overall false discovery rate of the joint causal relationships between an SGA to 5 or more target DEGs is smaller than 10−7. The S1 Fig shows that at this threshold, none of SGA was assigned as SGA-FI by random chance.

Cell culture and siRNA transfection

HGC27 (Sigma-Aldrich) and PC-3 (ATCC) cells were cultured according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The non-targeting and the CSMD3 and ZFHX4 siRNAs were obtained from OriGene (Rockville, MD). The siRNA sequences are as follow: si-CSMD3-1, GGUAUAUUACGAAGAAUUGCAGAGT; si-CSMD3-2, ACAAAUGGAGGAAUACUAACAACAG; si-ZFHX4-1, CGAUGCUUCAGAAACAAAGGAAGAC; si-ZFHX4-2, GGAACGACAGAGAAAUAAAGAUUCA. The siRNAs were transfected into cells using DharmaFECT transfection reagents for 48 hrs according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell proliferation and viability assays

Cell proliferation/viability was assayed by CCK-8 assay (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan). Briefly, HGC27 and PC3 cells were plated at a density of 3 x 103 cells/well in 96-well plates. After siRNA transfection for 3 or 6 days, CCK-8 solution containing a highly water-soluble tetrazolium salt WST-8 [2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, monosodium salt] was added to cells in each well, followed by incubation for 1–4 h. Cell viability was determined by measuring the O.D. at 450 nm. Percent over control was calculated as a measure of cell viability.

Transwell migration assay

Cell migration was measured using 24-well transwell chambers with 8 μm pore polycarbonate membranes (Corning, Corning, NY). SiRNA-transfected cells were seeded at a density of 7.5 x 104 cells/ml to the upper chamber of the transwell chambers in 0.5 ml growth media with 0.1% FBS. The lower chamber contained 0.9 ml of growth medium with 20% FBS as chemoattractant media. After 20 hrs of culture, the cells in the upper chamber that did not migrate were gently wiped away with a cotton swab, the cells that had moved to the lower surface of the membrane were stained with crystal violet and counted from five random fields under a light microscope.

Apoptotic assay

Apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometry analysis of annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) double stained cells using Vybrant Apoptosis Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, the cells after washing with PBS were incubated in annexin V/PI labeling solution at room temperature for 10 min, then analyzed in the BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

A. The plot shows the relationship of total number of SGAs being designated as SGA-FIs with respect to the threshold of calling an SGA-FI in random and real data. The x-axis shows the different thresholds, i.e., the number of DEGs predicted to be regulated by an SGA-FI, and the y-axis shows the number of significant SGA-FIs across all tumors. B. The plot shows the relationship of average number of SGAs being designated as SGA-FIs in a tumor with respect to the threshold of calling an SGA-FI in random and real data. The x-axis shows the different thresholds, i.e., the number of DEGs predicted to be regulated by an SGA-FI, and the y-axis shows the average number of significant SGA-FIs in a single tumor.

(TIF)

A. Comparison of distributions of the posterior probabilities of the highest candidate causal edges point from 3 most frequent SGAs to DEGs. B. Examples of 3 genes with high SGA frequency but without any high posterior probability causal edges emitting from them. C. Comparison of number of tumors called as SGA-FIs from the real dataset, randomly permutated DEG dataset and single SGA permutated dataset for the 6 most frequency SGAs.

(TIF)

A. SGA-FIs interacting network containing 536 SGA-FIs and 2669 edges. Blue nodes represent known cancer drivers and red nodes represent novel SGA-FIs. Node size indicates the number of its affected DEGs and edge width indicates the number of overlapped DEGs between two nodes. B-E. Top 15 SGA-FIs that share the most significant overlapping target DEGs with CDKN2A, PTEN, LRP1B, and MUC16. An edge between a pair of SGA-FI indicates that they share significantly overlapping target DEG sets, and the thickness of the line is proportional to negative log of the p-values of overlapping target DEG sets.

(TIF)

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge editorial assistance provided by Michelle Kienholz and technical assistance by Fan Yu and Soumya Luthra. The authors would like to thank Drs. Clark Glymour, Peter Spirtes, and Josh Stuart for discussions and suggestions.

Data Availability

PANCAN RNASeq data, mutation data, and copy number data are available in the Xena database under cohort TCGA Pan-Cancer (PANCAN). L1000 LINCS cell line perturbation data is available in GEO database under GSE70138. Source data are available from the Cancer Genome Atlas project website. Result data from this study are available as supplementary material of this publication.

Funding Statement

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant U54HG008540 awarded by the National Human Genome Research Institute through funds provided by the trans-NIH Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) initiative (www.bd2k.nih.gov). Funding also came from R01LM012011 and R00LM011673 awarded by the National Library of Medicine, from Grant #4100070287 awarded by the Pennsylvania Department of Health, and from Grant # PC150190 awarded by the Department of Defense. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Pennsylvania Department of Health or the Department of Defense. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502(7471):333–9. 10.1038/nature12634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Mermel CH, Robinson JT, Garraway LA, Golub TR, et al. Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature. 2014;505(7484):495–501. 10.1038/nature12912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciriello G, Miller ML, Aksoy BA, Senbabaoglu Y, Schultz N, Sander C. Emerging landscape of oncogenic signatures across human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45(10):1127–33. 10.1038/ng.2762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zack TI, Schumacher SE, Carter SL, Cherniack AD, Saksena G, Tabak B, et al. Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat Genet. 2013;45(10):1134–40. 10.1038/ng.2760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stransky N, Cerami E, Schalm S, Kim JL, Lengauer C. The landscape of kinase fusions in cancer. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4846 10.1038/ncomms5846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y, Schwab C, Ryan SL, Papaemmanuil E, Robinson HM, Jacobs P, et al. Constitutional and somatic rearrangement of chromosome 21 in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2014;508(7494):98–102. 10.1038/nature13115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maher CA, Wilson RK. Chromothripsis and human disease: piecing together the shattering process. Cell. 2012;148(1–2):29–32. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson MA, Kouzarides T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell. 2012;150(1):12–27. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.013 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feinberg AP, Koldobskiy MA, Gondor A. Epigenetic modulators, modifiers and mediators in cancer aetiology and progression. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(5):284–99. 10.1038/nrg.2016.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nature reviews Genetics. 2002;3(6):415–28. 10.1038/nrg816 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–74. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubio-Perez C, Tamborero D, Schroeder MP, Antolin AA, Deu-Pons J, Perez-Llamas C, et al. In silico prescription of anticancer drugs to cohorts of 28 tumor types reveals targeting opportunities. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(3):382–96. 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biankin AV, Piantadosi S, Hollingsworth SJ. Patient-centric trials for therapeutic development in precision oncology. Nature. 2015;526(7573):361–70. 10.1038/nature15819 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garraway LA, Verweij J, Ballman KV. Precision oncology: an overview. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(15):1803–5. 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.4799 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dees ND, Zhang Q, Kandoth C, Wendl MC, Schierding W, Koboldt DC, et al. MuSiC: identifying mutational significance in cancer genomes. Genome Res. 2012;22(8):1589–98. 10.1101/gr.134635.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499(7457):214–8. 10.1038/nature12213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djotsa Nono ABD, Chen K, Liu X. Comutational prediction of genetic drivers in cancer. eLS 2016. 10.1002/9780470015902.a0025331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adzhubei I, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2013;Chapter 7:Unit7 20. 10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter H, Chen S, Isik L, Tyekucheva S, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, et al. Cancer-specific high-throughput annotation of somatic mutations: computational prediction of driver missense mutations. Cancer Res. 2009;69(16):6660–7. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reva B, Antipin Y, Sander C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: application to cancer genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(17):e118 10.1093/nar/gkr407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N. Functional impact bias reveals cancer drivers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(21):e169 10.1093/nar/gks743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niu B, Scott AD, Sengupta S, Bailey MH, Batra P, Ning J, et al. Protein-structure-guided discovery of functional mutations across 19 cancer types. Nat Genet. 2016;48(8):827–37. 10.1038/ng.3586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bashashati A, Haffari G, Ding J, Ha G, Lui K, Rosner J, et al. DriverNet: uncovering the impact of somatic driver mutations on transcriptional networks in cancer. Genome Biol. 2012;13(12):R124 10.1186/gb-2012-13-12-r124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zack TI, Schumacher SE, Carter SL, Cherniack AD, Saksena G, Tabak B, et al. Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat Genet. 2013;45(10):1134–40. 10.1038/ng.2760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mermel CH, Schumacher SE, Hill B, Meyerson ML, Beroukhim R, Getz G. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 2011;12(4):R41 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Razi A, Banerjee N, Dimitrova N, Varadan V. Non-linear Bayesian framework to determine the transcriptional effects of cancer-associated genomic aberrations. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2015;2015:6514–8. Epub 2016/01/07. 10.1109/EMBC.2015.7319885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang H, Wei Q, Zhong X, Yang H, Li B. Cancer driver gene discovery through an integrative genomics approach in a non-parametric Bayesian framework. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(4):483–90. Epub 2016/11/01. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z, Ng KS, Chen T, Kim TB, Wang F, Shaw K, et al. Cancer driver mutation prediction through Bayesian integration of multi-omic data. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0196939 Epub 2018/05/09. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearl J. Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference. 2nd ed: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glymour C, Cooper G. Computation, Causation, and Discovery. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Visweswaran S, Angus DC, Hsieh M, Weissfeld L, Yealy D, Cooper GF. Learning patient-specific predictive models from clinical data. J Biomed Inform. 2010;43(5):669–85. 10.1016/j.jbi.2010.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper G, Cai C, Lu X. Tumor-specific Causal Inference (TCI): A Bayesian Method for Identifying Causative Genome Alterations within Individual Tumors. bioRxiv. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nica AC, Dermitzakis ET. Expression quantitative trait loci: present and future. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368(1620):20120362 Epub 2013/05/08. 10.1098/rstb.2012.0362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Battle A, Montgomery SB. Determining causality and consequence of expression quantitative trait loci. Hum Genet. 2014;133(6):727–35. Epub 2014/04/29. 10.1007/s00439-014-1446-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mermer T, Terek MC, Zeybek B, Ergenoglu AM, Yeniel AO, Ozsaran A, et al. Thrombopoietin: a novel candidate tumor marker for the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2012;23(2):86–90. Epub 2012/04/24. 10.3802/jgo.2012.23.2.86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naina HV, Harris S. Paraneoplastic thrombocytosis in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(19):1840; author reply Epub 2012/05/11. 10.1056/NEJMc1203095 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meraz IM, Savage DJ, Segura-Ibarra V, Li J, Rhudy J, Gu J, et al. Adjuvant cationic liposomes presenting MPL and IL-12 induce cell death, suppress tumor growth, and alter the cellular phenotype of tumors in a murine model of breast cancer. Mol Pharm. 2014;11(10):3484–91. Epub 2014/09/03. 10.1021/mp5002697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]