Abstract

This case report highlights utilization of image-guided, percutaneous transorbital direct cavernous sinus puncture to embolize an anteriorly draining carotid cavernous fistula (CCF) when conventional transarterial and transvenous approaches were not feasible. An 86-year-old man with a known posterior draining CCF developed acute unilateral proptosis, pain, and vision loss (“red-eyed shunt”). Cerebral angiogram revealed the dural CCF to be draining anteriorly into partially thrombosed ophthalmic veins. After failed transarterial and transvenous attempts, a percutaneous transorbital approach was used to successfully embolize the fistula using the Onyx Liquid Embolic System according to the visual needle path generated by the Seimens Syngo iGuide. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of percutaneous transorbital direct embolization of a CCF utilizing the Seimens Syngo iGuide.

Keywords: Carotid cavernous fistula, onyx liquid embolic system, percutaneous transorbital direct cavernous sinus puncture, Seimens Syngo iGuide

A carotid cavernous fistula (CCF) occurs when arterial blood from the internal or external carotid artery is shunted into the venous cavernous sinus. We report a patient with a CCF who failed conventional transarterial and transvenous embolization but had successful direct transorbital access of the cavernous sinus.

CASE REPORT

An 86-year-old man presented to the emergency room with 6 days of unilateral severe proptosis, pain, and vision loss in the left eye. Past medical history was significant for medically controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and primary open angle glaucoma. He reported multiple prior intermittent episodes of blurry vision and mild swelling of the left eye over the past year. Cerebral angiogram performed a year earlier as part of the workup for possible amaurosis fugax incidentally revealed a right-sided, posterior draining, slow-flow (“white-eyed shunt”) CCF filling from dural branches of the left and right internal carotid arteries (Barrow type B fistula) with exclusive drainage via the left inferior petrosal sinus. Because there was no evidence of ocular motor cranial neuropathy (e.g., sixth nerve palsy), headache, or pain, a decision was made to observe the patient.

The patient presented a year later with acute vision loss to hand motions, marked lid edema, extensive conjunctival chemosis, and complete ophthalmoplegia in the left eye. The exam of the right eye was normal. Intraocular pressure was markedly elevated in the left eye. There was a left relative afferent pupillary defect. An emergent lateral canthotomy and inferior cantholysis were performed. Computed tomography (CT) scan suggested a partially thrombosed superior ophthalmic vein (SOV) and cavernous sinus. Catheter angiography confirmed a CCF involving the intercavernous sinus draining directly into the left cavernous sinus and partially thrombosed SOV. Attempted transarterial embolization was aborted, because the risk of ischemic nerve damage and resultant cranial nerve palsies was high. Transvenous embolization was not feasible because thrombosis in the retro-orbital segment of the SOV prevented vessel access by direct and indirect (via facial vein) approaches (Figure 1). Attempts to cannulate the inferior petrosal sinus and pterygomaxillary plexus failed due to the presence of bilateral thromboemboli.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative angiogram, transvenous attempt. Utilizing a direct percutaneous approach, two needles were used to try to select the inferior ophthalmic vein but were unsuccessful. Subsequently, a stiff micropuncture set was used to select the most anterior aspect of the left cavernous sinus.

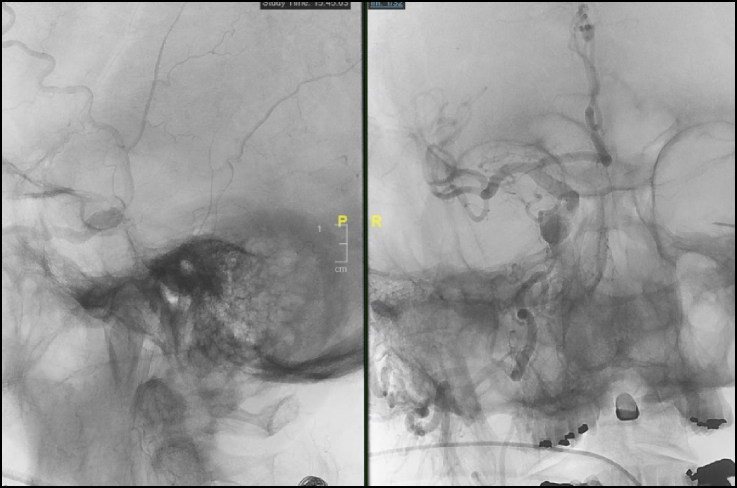

The patient underwent successful percutaneous transorbital direct cavernous sinus puncture and CCF embolization using the Onyx Liquid Embolic System and conventional coils introduced into the cavernous sinus according to the ideal virtual needle path generated by the Siemens Syngo® iGuide system. Posttreatment angiography showed complete obliteration of the CCF (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Intraoperative angiogram, fistula embolization. Multiple coils and Onyx 34 embolization material were used to obliterate the fistula.

DISCUSSION

CCFs that drain posteriorly into the inferior or superior petrosal sinuses can spare the ophthalmic venous system and produce a white-eyed shunt. Patients with a posterior draining CCF may be asymptomatic or symptomatic (e.g., headache, facial or eye pain, and diplopia—typically from a sixth nerve palsy). However, anterior drainage involving the ophthalmic veins may cause ophthalmic venous hypertension and resultant orbital congestion (“red-eyed shunt”). In the case above, onset of symptoms paralleled angiographic evidence of flow reversal from partial thrombosis. Treatment was initiated after the development of an acute transition from white-eyed to red-eyed shunt, markedly elevated intraocular pressure, and acute visual loss from presumed posterior ischemic optic neuropathy.

Acute thrombosis can convert a previously asymptomatic “white-eye” CCF to a symptomatic “red-eye” CCF. Therefore, paradoxical worsening of ocular symptoms can occur despite spontaneous thrombosis and possible impending closure of a CCF.1 Choroidal detachments and angle closure glaucoma are also associated with spontaneous fistula resolution.2 Rarely, progression to orbital compartment syndrome has also been reported.3 Clinically, patients with anteriorly draining red-eyed shunts most often present with a triad of proptosis, conjunctival chemosis, and a cranial bruit. Additional signs and symptoms such as pulsatile exophthalmos, limited ocular motility, and vision loss may also be present.4

Endovascular treatment of CCF is the procedure of choice. In rare cases, transarterial and transvenous approaches (via cannulation of the SOV directly or by way of the facial vein, pterygomaxillary venous plexus, or inferior petrosal sinus) are not available, and percutaneous transorbital direct cavernous sinus puncture with embolization has been reported.

Direct cavernous sinus puncture has historically been a last resort to access the cavernous sinus due to the risk of disturbing the angioarchitecture supplying cranial nerves 7, 9, 10, 11, and 12. The Siemens Syngo iGuide system mitigates this risk by mapping the vasculature and generating an ideal virtual needle path that respects the nervous and vascular structures within the cavernous sinus. This system uses 2D and 3D digital subtraction angiography and intraoperative cone-beam CT images to project multiplanar, volume-rendered models of the cavernous sinus within the 3D workstation of the neurointerventional suite. The needle is advanced percutaneously into the orbit along an optimized trajectory, protecting the angioarchitecture, using integrated C-arm angiography equipment. Upon confirmation of needle placement with intraoperative cone-beam CT, platinum coils are introduced into the fistula through a Headway Duo Microcatheter to anchor the Onyx liquid embolic material.

In conclusion, acutely symptomatic CCFs can occur from thrombosis and flow reversal of previously asymptomatic shunts. The Siemens Syngo iGuide system enhances the safety of CCF embolization via the direct percutaneous transorbital approach.

References

- 1.Hawke SH, Mullie MA, Hoyt WF, Hallinan JM, Halmagyi GM. Painful oculomotor nerve palsy due to dural-cavernous sinus shunt. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:1252–1255. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520470126040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thinda S, Melson MR, Kuchtey RW. Worsening angle closure glaucoma and choroidal detachments subsequent to closure of a carotid cavernous fistula. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012;12:12–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sia PI, Sia DIT, Scroop R, Selva D. Orbital compartment syndrome following transvenous embolization of carotid-cavernous fistula. Orbit. 2014;33:52–54. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2013.841717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhry IA, Elkhamry SM, Al-Rashed W, Bosley TM. Carotid cavernous fistula: opthalmological implications. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2009;16:57–63. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.53862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]