Organizational silence is a term that illustrates the lack of dialogue when stakes are high in organizational (medical) teams. This silence has individual, social, and organizational factors and contributes to medical errors.1 Often, medical errors are not addressed due to a lack of appropriate team dialogue, because team members’ psychological safety is lacking.2 One-way communication is important, but just as important is two-way dialogue, which requires both psychological safety and mutual respect (trust). Medical errors are happening at an alarming rate, and even more alarming is that the errors could be prevented if factors like psychological safety and mutual respect were present within the team.

PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY

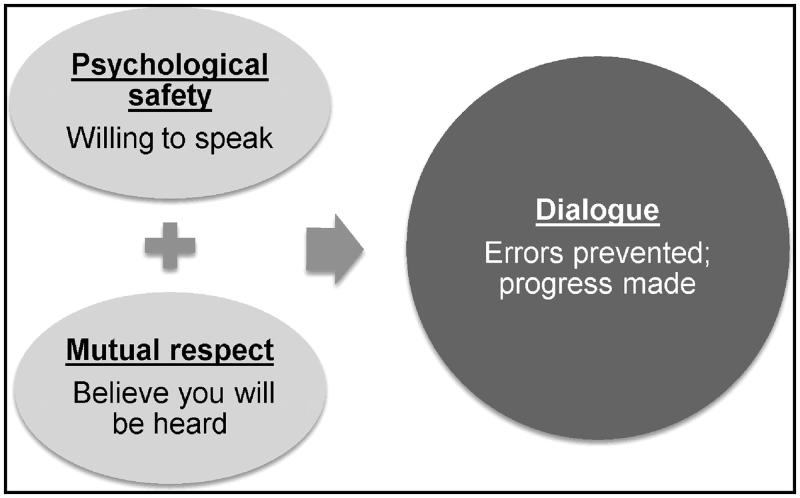

Psychological safety essentially “measures whether team members feel they can bring up a topic”3 or “feel comfortable sharing concerns and mistakes without fear of embarrassment or retribution”4 and is an important first step in the dialogue process (Figure 1). If team members feel as though bringing up difficult topics will not result in retaliation or other negative consequences, they are more likely to be engaged and will attempt to solve problems, allowing for learning, growth, and ultimately better performance.5

Figure 1.

Creating team dialogue.

Potential barriers to psychological safety are poor relationships and social status.6 Building trust and relationships is key to team members feeling comfortable in bringing up a topic. If team relationships are already on shaky ground, then the likelihood of someone feeling safe enough to bring up an error or concern is minimal, because negative emotions engage the sympathetic nervous system and trigger avoidance.7 Social status or hierarchy can also contribute to a lack of dialogue and, in turn, errors.8 Hierarchy reduces two-way dialogue because established norms state that the highest-ranking person should do the telling and the lowest-ranking person should do the listening. These norms, if not addressed or changed, keep lower-ranking people on a team from speaking up,9 thus adding to the issues of hierarchy and power and decreasing psychologically safe environments.

MUTUAL RESPECT

The next step in the process is mutual respect, which examines “whether team members feel that other members of the team want to hear their ideas.”3 Much of the focus on psychological safety does not account for the crucial second component of mutual respect. Mutual respect is the component that will allow the dialogue to continue and not be a one-time occurrence. When individuals speak up, they must feel that their contributions are valued and result in consideration of their ideas. In a clinical setting, for example, say an operating nurse speaks up while a surgeon is closing a wound and says, “I haven’t finished our count; I don’t think we have everything. Can we please pause for clarity?” If she is dismissed with the comment “then count again,” what is the likelihood that she will speak up next time? If, instead, the surgeon stopped and said, “Everyone stop while we finish our count,” imagine the amount of mutual respect that would have been established, enabling the nurse to feel heard and validating the role of all team members. Most important, this approach would ensure that no instruments were left in the patient.

DIALOGUE

Dialogue tends to involve relationship-based communication rather than task-based conversation. Relationship-based communication has yielded better outcomes than task-based communication,10 yet so much of the clinical environment continues to be based on task and hierarchical communication, both of which are often one-way. Dialogue should be a give and take of information that is allowed through psychological safety and mutual respect. Dialogue ensures that both people are heard in a conversation rather than one person being the sender and the other being the receiver. Because all team members have information to share regarding patient care, dialogue with psychological safety and mutual respect is imperative. Often nurses spend more time with the patient than the physician, so their contribution would add efficiency and quality to clinical decision making, yet dialogue has to be encouraged by breaking down the hierarchy, ensuring that both parties feel psychologically safe to contribute, as well as having mutual respect (trust and being heard).

CONCEPT DESCRIBED

Although respect has been deemed more important than psychological safety,3 psychological safety is the first step in team members speaking up. An individual must first believe that there will be no negative repercussions for speaking up to be willing to put his or her thoughts on the line. For example, if a team is working in an operating room and one of the team members notices that an instrument is not accounted for, that team member must be working in a setting that allows opportunities to speak up without retaliation. Although this should be enough, without adding respect to the equation, team members may not share their concerns or, just as devastating, they may share but not be heard by team leadership. To illustrate this, we go back to our original example. The team member in the operating room feels safe to notify the leader of the team about the missing instrument but hesitates because in the past that leader did not listen to (respect) other teammates’ contributions or, just as bad, the team member does speak up and the team leader does not demonstrate respect about what is shared, ignoring the warning. Both psychological safety and respect have to be present for dialogue to occur.

BARRIERS TO THIS FORMULA

An important barrier to consider for this formula is individual perception and ensuring a mutually agreed-upon narrative. One individual could perceive a situation as both safe and respectful, whereas another may perceive it completely differently. Knowing that misperceptions can occur, leaders should not only model the appropriate behavior but also articulate what they are doing and then follow up, closing the loop of communication to ensure that everyone has the same “takeaways” from the situation. For example, many institutions claim to have both safe and respectful environments that include appropriate reporting mechanisms. Although on paper this may be accurate, in reality reporting mechanisms do not always follow up with individuals, leaving them to believe that they were not heard and, even if they do follow up, there are often no consequences for the incident, breaking mutual respect.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To reduce organizational silence, the concept of humble inquiry can be employed, which increases psychological safety and mutual respect. Humble inquiry was introduced in 2013 as a way of approaching a situation with curiosity and interest, communicating and actually listening to people rather than focusing so much on telling.9 Telling is the current standard in the hierarchical culture of medicine, so asking questions moves toward change and potentially negates the social rules (i.e., hierarchy) to allow progress in building psychological safety and mutual respect. Humble inquiry requires a certain amount of vulnerability because one has to ask a question without knowing the answer and has to be prepared to receive information openly and without judgment. The inquiry cannot be leading or statement based but rather must be a true interest in gaining knowledge or perspective from the other party. For people on the lower end of the hierarchy, this approach by higher-ups creates a temporary subordination, reducing barriers and creating psychological safety.9

In addition to using humble inquiry, we recommend two specific actionable ideas: avoid making assumptions and develop rapport. When working with a team, or anyone for that matter, it is important to avoid making assumptions about their intent. Making assumptions about another person’s intent can end in conflict and confusion and shut down the opportunity for dialogue. Even if the initial assumption proves to be true, it is better to start the conversation with open inquiry, which will engage the other party rather than put him or her on the defensive. Putting the other person on the defensive is a nonstarter and defeats the purpose of working as a team. Developing personal rapport creates a stronger relationship and interdependence for the team. Rapport and team engagement outside of required clinical encounters predict productivity.9,11 So, rapport can affect productivity, safety, and effectiveness.

Finally, moving and changing culture is one of the most difficult tasks for a leader, so instead of trying to take on a huge idea, start with humble inquiry, minimizing assumptions, and developing rapport. These things should encourage psychological safety, mutual respect, and, most important, dialogue, negating organizational silence and minimizing clinical errors.

References

- 1.Henriksen K, Dayton E. Organizational silence and hidden threats to patient safety. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(Pt 2):1539–1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Derickson R, Fishman J, Osatuke K, Teclaw R, Ramsel D. Psychological safety and error reporting within Veterans Health Administration hospitals. J Patient Saf. 2015;11:60–66. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wholey DR, Disch J, White KM, et al. Differential effects of professional leaders on health care teams in chronic disease management groups. Health Care Manage Rev. 2014;39:186–197. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182993b7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edmondson A. The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delizonna L. High-performing teams need psychological safety. Here’s how to create it. Harv Bus Rev 2017;2–5. https://hbr.org/2017/08/high-performing-teams-need-psychological-safety-heres-how-to-create-it

- 6.Liu W, Tangirala S, Lam W, Chen Z, Jia RT, Huang X. How and when peers’ positive mood influences employees’ voice. J Appl Psychol. 2015;100:976–989. doi: 10.1037/a0038066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jack AI, Boyatzis RE, Khawaja MS, Passarelli AM, Leckie RL. Visioning in the brain: an fMRI study of inspirational coaching and mentoring. Soc Neurosci. 2013;8:369–384. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2013.808259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calhoun AW, Boone MC, Porter MB, Miller KH. Using simulation to address hierarchy-related errors in medical practice. Perm J. 2014;18:14–20. doi: 10.7812/TPP/13-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schein E. Humble Inquiry: The Gentle Art of Asking Instead of Telling. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiarchiaro J, White DB, Ernecoff NC, Buddadhumaruk P, Schuster RA, Arnold RM. Conflict management strategies in the ICU differ between palliative care specialists and intensivists. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:934–942. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pentland A. The new science of building great teams. Harv Bus Rev. 2012;90:60–69.23074865 [Google Scholar]