Abstract

Study objective:

Professional guidelines recommend 72-hour cardiac stress testing following an emergency department (ED) evaluation for possible acute coronary syndrome (ACS). There is limited data on real world compliance rates and impact on patient outcomes. Our aim is to describe rates of completion of noninvasive cardiac stress testing and associated 30-day major adverse cardiac events (MACE).

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective analysis of ED encounters from June 2015 to June 2017 across 13 community EDs within an integrated health system in Southern California. The study population included all adults with a chest pain diagnosis, troponin value, and discharge with an order for an outpatient cardiac stress test. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who completed an outpatient stress test within the recommended 3 days, 4-30 days, or not at all. Secondary analysis described the 30-day incidence of MACE.

Results:

During the study period, 24,459 patients presented with a chest pain evaluation requiring troponin analysis and stress test ordering from the ED. Of these, we studied the 7,988 patients who were discharged home to complete diagnostic testing, having been deemed appropriate by the treating clinicians for an outpatient stress test. The stress test completion rate was 31.3% within 3 days, 58.7% between 4-30 days, and 10.0% who did not complete the ordered test. The 30-day rates of MACE were low (death 0.0%, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) 0.7%, and revascularization 0.3%). Rapid receipt of stress testing was not associated with improved 30-day MACE (OR=0.92, 95% CI: 0.55-1.54).

Conclusion:

Fewer than one-third of patients completed outpatient stress testing within the guideline-recommended 3 days following initial evaluation. More importantly, the low adverse event rates suggest that selective outpatient stress testing is safe. In this cohort of patients selected for outpatient cardiac stress testing in a well-integrated health system, there does not appear to be any associated benefit of stress testing within 3 days, nor within 30 days, compared to those who never received testing at all. The lack of benefit of obtaining timely testing, in combination with low rates of objective adverse events, may warrant reassessment of the current guidelines.

Background

With over 7 million annual visits, chest pain remains the second most common reason for presentation of adults to the emergency department (ED) in the United States.1 A minority of these patients have acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and most do not even have heart disease. However, stratifying this cohort is challenging, and the inappropriate discharge of patients with high risk for ACS is associated with high morbidity.2

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommends noninvasive cardiac stress testing within 72 hours, after an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has been excluded by serial electrocardiogram (ECG) and cardiac biomarker testing (Class IIA recommendation).3 However, little is known of the actual completion rates of guideline-recommended early outpatient stress testing and of the association of such testing on patient outcomes. Three studies have looked at early outpatient stress test completion in the United States.4–6 All were single center studies with limited sample sizes, restricted inclusion to low-risk patients, and involved targeted efforts (such as follow-up phone calls) to maximize completion rates. Two of these studies assessed associated major adverse cardiac events (MACE). One evaluated MACE at 6 months based on stress test completion status within that time interval4, while the other assessed adverse cardiac events in 30 days or death in 12 months based on stress test completion status within that 12-month interval.5 Given that clinicians are most sensitive to the immediate outcomes following ED evaluation, these long-term MACE timeframes may provide only limited insight to inform ED clinical decision making and disposition planning.

Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) EDs adopted a standard recommendation of using a HEART pathway for patients evaluated for suspected ACS in 2016.7,8 Our objective was to describe rates of completion of early noninvasive cardiac stress testing and associated 30-day MACE. Our study aims to specifically address several of these knowledge gaps by examining all outpatient stress testing from the ED in a large volume, multi-center, community setting.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a retrospective study of eligible encounters occurring from June 2015 through June 2017 at 13 EDs of KPSC. KPSC is an integrated health system providing health care for over four million members. KPSC hospitals deliver care for over 1 million ED visits annually with volumes of the study sites ranging from 25,000 to 95,000 ED visits per year. Of these ED encounters, approximately 80% are health plan members. One center has an emergency medicine residency program. All sites use the same troponin lab assay (Beckman Coulter Access AccuTnI+3), and ED physicians have the ability to order noninvasive cardiac testing as part of the discharge and follow-up plan.

Study Participants

ED encounters were included for adult Kaiser Permanente health plan members (≥18 years of age) who were discharged from the ED after an evaluation for chest pain, and who had a troponin lab test and an ED order for outpatient cardiac stress test. We excluded patients who had a do not resuscitate (DNR) or hospice status, had an ED AMI diagnosis or troponin level of > 0.5 ng/ml, died in the ED, transferred from another hospital, or completed a stress test prior to discharge. Chest pain diagnosis was defined using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision (ICD-9 and ICD-10) codes, and noninvasive cardiac tests were identified by CPT codes (Appendix A).

Outcome and Covariate Measurements

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who completed an early outpatient stress test within 72 hours from ED discharge. Included in the primary outcome is the proportion of patients who completed a stress test within 4-30 days or not at all. We also measured 30-day incidence of MACE (all-cause death, AMI, and revascularization by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)), as a secondary outcome to assess its relationship with early completion (Appendix A). Midway through the study period in May 2016, all study sites implemented decision support to capture HEART scores and to incorporate this tool into routine ED care.7,8 We report the completion rates of stress testing stratified by this subgroup of encounters with documented low- (0-3), moderate- (4-6), or high- (7-10) risk HEART scores. Mortality data was obtained from KPSC administrative records, which were supplemented with data from the State of California and Social Security Administration.

Relevant demographic, clinical, comorbidity, and physician data were also obtained using structured data from electronic health and administrative records. Patient age, gender, and race/ethnicity were obtained from administrative records, and patient socioeconomic status (SES) was measured using the census block-level median income based on patients’ home ZIP codes. Cardiac risk factors measured were cardiac-related comorbidities as defined by using codes for the modified Elixhauser index9 (e.g. hypertension and diabetes), body mass index (BMI) measured from either ED initial assessment or the most recently available from a previous encounter, and EMR-recorded self-reported smoking history (“Active,” “Second-hand,” “Quit,” and “Never”). Southern California Permanente Medical Group physicians were distinguished from per-diem and other employee types using administrative records.

Additionally, we considered that non-clinical, system-level factors could be key drivers of 72-hour completion. For this reason, we also recorded the KPSC medical center at which ED encounters occurred, as well as day of the week and hour of the day of discharge.

Statistical Analysis

Patient, visit, physician, and facility characteristics were summarized using means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Due to low levels of missingness in our continuous variables, we excluded patients missing BMI (n=60) or SES (n=7) from multivariable analyses. For missing categorical outcomes (smoking history, n=146), we included an “Unknown” category.

The outcome of interest was completion of an ED-ordered stress test within 72 hours from ED discharge. We calculated this at the patient-level, as well as medical-center level to assess variability between facilities. For the former, we used logistic regression to estimate the multivariable-adjusted associations between early stress test completion and the patient, visit, physician, and facility characteristics listed above. We also included an interaction term between medical center and day of the week to assess whether discharges occurring at the end of the week (Thursday-Friday) had different completion rates by medical center. We examined separate and composite 30-day MACE rates for those completing noninvasive testing within 72 hours compared to those who did not. We summarized all model results using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). This study was approved by the KPSC Institutional Review Board.

Results

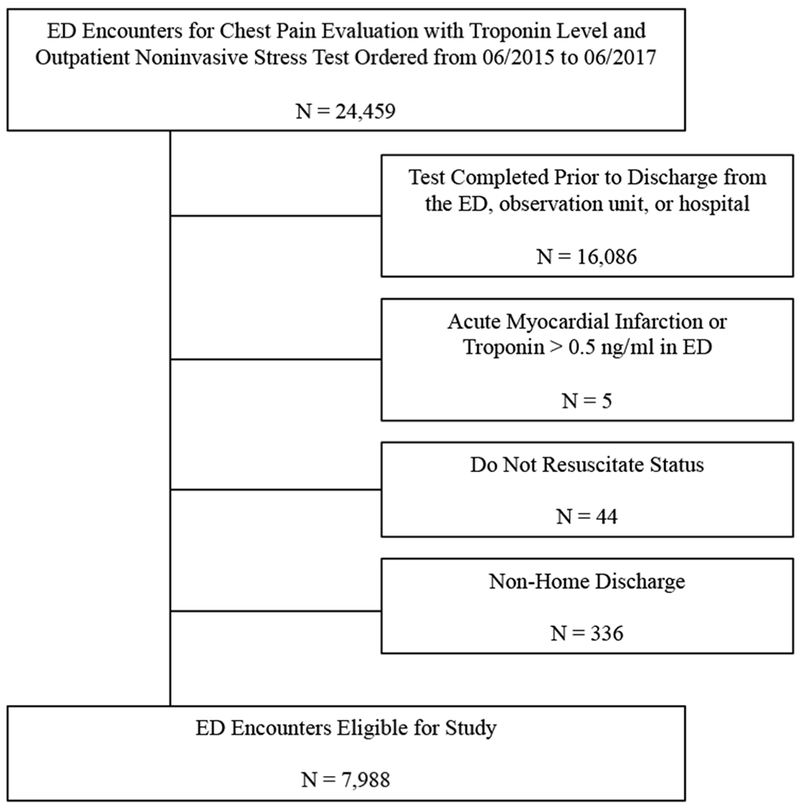

In the study period there were a total of 24,459 ED encounters for chest pain evaluation prompting troponin analysis and noninvasive stress test ordering. Of these, 7,988 patients were discharged to complete cardiac stress testing as an outpatient (Figure 1). Of this cohort, 2,497 patients (31.3%) completed a stress test within 72 hours of ED discharge, while 4,695 (58.7%) did so within 4-30 days and 796 (10.0%) did not complete testing within 30 days (Table 1). Among the tests ordered, 6,746 (84.5%) were exercise or pharmacologic stress ECG, 1,118 (14.0%) were exercise or pharmacologic stress echocardiogram, and 124 (1.5%) were myocardial perfusion imaging.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study cohort used for analysis.

Table 1.

Emergency Department patient characteristics for adults assessed for possible acute coronary syndrome discharged with an outpatient noninvasive cardiac stress test order. Study sample is stratified by timing of test completion.

| Noninvasive Test Completion Timeframe |

Total (N=7988) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within 3 days (N=2497) | 4 to 30 days (N=4695) | None within 30 days (N=796) | ||

| Age, Mean (SD) | 55.0 (11.50) | 55.4 (11.82) | 55.6 (11.68) | 55.3 (11.71) |

| Female, N (%) | 1351 (54.1) | 2606 (55.5) | 479 (60.2) | 4436 (55.5) |

| Race, N (%) | ||||

| White | 1179 (47.2) | 2257 (48.1) | 413 (51.9) | 3849 (48.2) |

| Black | 407 (16.3) | 672 (14.3) | 110 (13.8) | 1189 (14.9) |

| Asian | 303 (12.1) | 552 (11.8) | 91 (11.4) | 946 (11.8) |

| Alaska Native/Pacific Islander | 42 (1.7) | 94 (2.0) | 18 (2.3) | 154 (1.9) |

| Others | 566 (22.7) | 1120 (23.9) | 164 (20.6) | 1850 (23.2) |

| Elixhauser Score, Mean (SD) | 2.4 (2.07) | 2.5 (2.14) | 2.5 (2.24) | 2.5 (2.13) |

| Cardiac Risk Factors, N (%) | ||||

| Coronary Artery Disease | 114 (4.6) | 239 (5.1) | 44 (5.5) | 397 (5.0) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 26 (1.0) | 51 (1.1) | 13 (1.6) | 90 (1.1) |

| Diabetes | 472 (18.9) | 922 (19.6) | 146 (18.3) | 1540 (19.3) |

| Hypertension | 1015 (40.6) | 2081 (44.3) | 348 (43.7) | 3444 (43.1) |

| Liver Disease | 210 (8.4) | 395 (8.4) | 63 (7.9) | 668 (8.4) |

| Peripheral Vascular Disorders | 279 (11.2) | 589 (12.5) | 105 (13.2) | 973 (12.2) |

| Body Mass Index | ||||

| Normal | 509 (20.5) | 922 (19.8) | 165 (20.9) | 1596 (20.1) |

| Overweight | 905 (36.5) | 1678 (36.0) | 284 (35.9) | 2867 (36.2) |

| Obese | 1067 (43.0) | 2057 (44.2) | 341 (43.2) | 3465 (43.7) |

| Missing | 16 | 38 | 6 | 60 |

| Smoking Behavior, N (%) | ||||

| Never | 1685 (67.5) | 3080 (65.6) | 514 (64.6) | 5279 (66.1) |

| Quit | 595 (23.8) | 1207 (25.7) | 205 (25.8) | 2007 (25.1) |

| Passive | 11 (0.4) | 30 (0.6) | 5 (0.6) | 46 (0.6) |

| Active | 158 (6.3) | 297 (6.3) | 55 (6.9) | 510 (6.4) |

| Missing | 48 (1.9) | 81 (1.7) | 17 (2.1) | 146 (1.8) |

| ED Encounter Day of the Week | ||||

| Saturday through Wednesday | 2105 (84.3) | 2963 (63.1) | 532 (66.8) | 5600 (70.1) |

| Thursday through Friday | 392 (15.7) | 1732 (36.9) | 264 (33.2) | 2388 (29.9) |

In comparing the early completion group to all others who did not receive a stress test within 72 hours of discharge, patient characteristics were similar in age, gender, race, and cardiac-specific comorbidities with the exception of hypertension (Table 1, Appendix B Table 1). In the multivariable-adjusted model, no patient demographic, clinical, or comorbidity characteristics, or ED physician characteristics, were significantly associated with 72-hour test completion (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratio estimates and confidence intervals for 72-hour noninvasive cardiac stress test completion among Emergency Department patients evaluated for possible acute coronary syndrome.

| Effect | Estimate | 95% Confidence Limits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 65+ vs 18-47 years | 0.907 | 0.76 | 1.082 |

| 55-65 vs 18-47 years | 0.939 | 0.805 | 1.095 |

| 47-55 vs 18-47 years | 1.03 | 0.88 | 1.205 |

| Female vs Male | 0.928 | 0.829 | 1.039 |

| Race | |||

| Alaska Native/Pacific Islander vs White | 0.834 | 0.551 | 1.262 |

| Asian vs White | 0.906 | 0.756 | 1.085 |

| Black vs White | 0.84 | 0.706 | 0.999 |

| Others vs White | 0.923 | 0.797 | 1.067 |

| Household Median Income (per $10,000) | 0.986 | 0.965 | 1.007 |

| Coronary Artery Disease: No vs Yes | 1.08 | 0.834 | 1.4 |

| Elixhauser Score | |||

| 1-2 vs 0 | 0.995 | 0.849 | 1.167 |

| 3-4 vs 0 | 0.968 | 0.807 | 1.161 |

| 5+ vs 0 | 0.922 | 0.746 | 1.14 |

| Body Mass Index | |||

| Overweight vs Normal | 1.014 | 0.868 | 1.185 |

| Obese vs Normal | 1.011 | 0.861 | 1.187 |

| Physician Affiliation: Per Diem vs Full-Time KPSC | 1.091 | 0.968 | 1.231 |

| ED Visit Day of Week: Saturday-Wednesday vs Thursday-Friday | 3.631 | 3.174 | 4.154 |

| ED Visit Year: 2015 vs 2017 | 0.97 | 0.832 | 1.132 |

| ED Visit Year: 2016 vs 2017 | 0.919 | 0.807 | 1.047 |

| Medical Center | |||

| Medical Center 1 vs 13 | 0.228 | 0.173 | 0.301 |

| Medical Center 2 vs 13 | 0.021 | 0.012 | 0.037 |

| Medical Center 3 vs 13 | 0.041 | 0.03 | 0.057 |

| Medical Center 4 vs 13 | 0.165 | 0.129 | 0.211 |

| Medical Center 5 vs 13 | 0.296 | 0.22 | 0.397 |

| Medical Center 6 vs 13 | 0.707 | 0.538 | 0.929 |

| Medical Center 7 vs 13 | 0.094 | 0.072 | 0.122 |

| Medical Center 8 vs 13 | 0.46 | 0.359 | 0.589 |

| Medical Center 9 vs 13 | 0.09 | 0.064 | 0.127 |

| Medical Center 10 vs 13 | 0.168 | 0.132 | 0.214 |

| Medical Center 11 vs 13 | 0.041 | 0.03 | 0.054 |

| Medical Center 12 vs 13 | 0.016 | 0.009 | 0.028 |

Abbreviations: KPSC = Kaiser Permanente Southern California

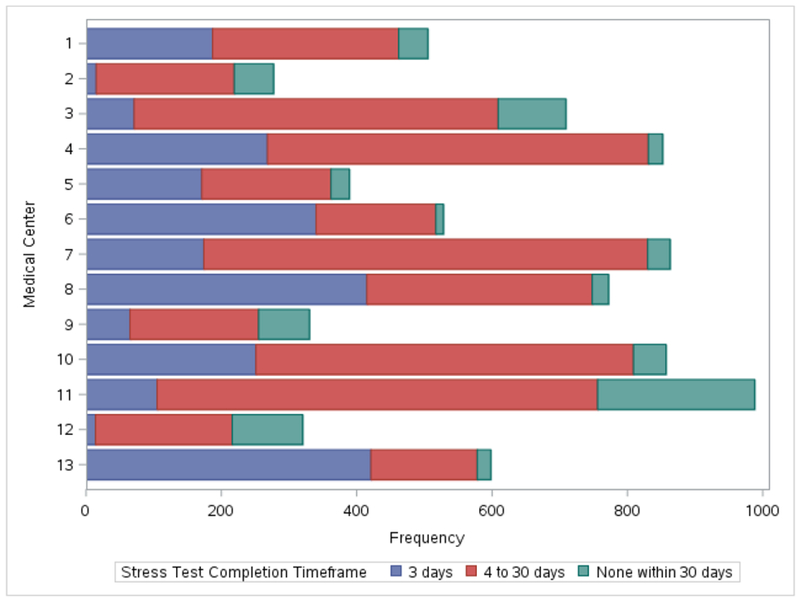

In contrast, system or non-clinical factors had stronger associations with receipt of 72-hour stress testing than clinical characteristics. Specifically, the day of the week had a large effect, with Thursday-Friday discharges having much lower rates of 72-hour completion than those occurring Saturday-Wednesday (15.7% vs. 84.3%) (Table 1). Compared to Thursday-Friday discharges, those occurring Saturday-Wednesday were 3.6 times as likely to result in early stress test completion (95% CI: 3.17-4.15) (Table 2). There is also a large amount of variability by medical center, ranging from less than 10% to nearly 70% for early completion (Figure 2). Using medical center 13 as comparator because it had the highest completion rate, patients discharged from other medical centers were anywhere from 30% to 98% less likely to have early completion of stress tests (Table 2). These two statistically significant associations remained after adjustment for the relevant patient, visit, physician, and facility characteristics. There was also a statistically significant interaction between medical center and discharge day-of-week, where the odd ratios of early completion for Saturday-Wednesday compared to Thursday-Friday ranged from 1.6 to 8.2 across the 13 medical centers (Appendix B Table 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of noninvasive cardiac stress test completion timing stratified by each of 13 Emergency Department Medical Centers.

There were no all-cause deaths within 30 days. The rates of other types of 30-day MACE were low with AMI at 0.7% and revascularization by PCI or CABG at 0.3%. Furthermore, rapid receipt of stress testing was not associated with improved adverse outcomes (Table 3), as patients completing stress testing within 72 hours were as likely to experience 30-day MACE compared to those who did not (OR=0.92, 95% CI: 0.55-1.54). Subgroup analysis of 2,151 encounters with documented HEART scores (1,560 low, 584 moderate, and 7 high risk) showed that different risk pools did not impact the timing of follow-up stress testing (Appendix B Table 1).

Table 3.

30-day major adverse cardiac outcomes stratified by timing of noninvasive cardiac stress test completion after an Emergency Department visit for suspected acute coronary syndrome.

| Noninvasive Test Completion Timeframe |

Total (N=7988) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within 3 days N=2497) | 4 to 30 days (N=4695) | None within 30 days (N=796) | ||

| Death, N | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AMI, N (%) | 19 (0.8) | 30 (0.6) | 5 (0.6) | 54 (0.7) |

| PCI, N (%) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (<0.1) | 0 | 4 (0.1) |

| CABG, N (%) | 6 (0.2) | 7 (0.1) | 0 | 13 (0.2) |

| Unstable Angina, N (%) | 18 (0.7) | 24 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | 43 (0.5) |

| MACE, N (%) | 27 (1.1) | 39 (0.8) | 5 (0.6) | 71 (0.9) |

Abbreviations: AMI = acute myocardial infarction. CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting. PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention. MACE = major adverse cardiac events (includes death, AMI, PCI, and CABG).

Discussion

Our study of 7,988 ED encounters resulting in outpatient noninvasive cardiac testing found a 72-hour completion rate of 31.3%, with 90.0% completing within 30 days of the ED visit. Adverse outcome rates at 30 days were very low with 0 deaths, 54 AMIs (0.7%), 4 PCI procedures (0.1%), and 13 CABG procedures (0.2%). Our results further suggest that early outpatient stress testing is not associated with lower MACE rates and may question if this population benefits from noninvasive testing at all.

Outpatient test completion rates previously reported in the literature have been the result of single site performance improvement efforts. Two of these studies were at academic centers and found 72-hour completion rates of 6% (27 of 448 patients)5 and 62% (170 of 275 patients).6 A third study, performed over a decade ago at a Kaiser Permanente community ED, found a 96-hour completion rate of 68% (613 of 979 patients).4 In these prior studies, targeted adherence to test completion was the primary objective of an accelerated chest pain protocol or discharge from a designated ED chest pain unit. In contrast, our study investigated follow-up outcomes based on current practice among a large network of community EDs where an outpatient noninvasive test order was placed from the ED.

Our study shows that despite the advantages of an integrated health system with the availability of ED-based referral for stress testing, the 72-hour guideline concordance rate is low. For patients without the benefit of a similar health system mechanism to facilitate outpatient referral, the ability to complete testing within 72 hours may be even more limited.

Even with low guideline concordance, 30-day MACE rates were nevertheless very low for all categories. Previously, Meyer et al. similarly found infrequent adverse events among eligible patients who completed stress testing within any time frame (1-month AMI rate of 0.1% and 6-month death, AMI, PCI, and CABG rates of 0%, 0.2%, 0.7%, and 0%, respectively). Milano et al. reported 12-month adverse events, finding a MACE rate of 0% among patients who received stress testing at any point, and 5 all-cause deaths (1.1%) and no AMI, PCI, or CABG among those who did not receive testing. With such a low event rate, our study was not powered to detect differences in MACE across all stress test completion timeframes. However, such few adverse events suggest appropriate assessment of safe discharges from the ED and no identifiable benefit of early outpatient noninvasive stress testing for this population.

This study adds to the recent literature that challenges routine stress testing.10–13 Observational reports suggest that current use of early noninvasive tests leads to overtreatment without objective benefit. In a retrospective cohort of 421,774 privately-insured patients, stress ECG, stress myocardial perfusion, and coronary computed tomography angiography were associated with increased rates of invasive coronary angiograms and revascularization without reduction in AMI risk, compared to no-testing.11 Similarly, in another retrospective cohort of 926,633 privately-insured patients, noninvasive testing or coronary angiography within 30 days of ED presentation was associated with increased rates of invasive coronary angiograms and revascularization without reduction in AMI admissions.12 At 224 hospitals, higher rates of noninvasive testing were correlated with increasing odds of admission, invasive angiograms, and revascularization, without reducing AMI risk.13 Accordingly, the American College of Emergency Physicians recently recommended against routine diagnostic testing (coronary CT angiography, stress testing, myocardial perfusion imaging) prior to discharge in low-risk patients in whom AMI has been ruled out (Level B recommendation).14

Despite the lack of evidence of benefit, patients are often admitted (e.g. to inpatient or observation status) to facilitate early noninvasive testing, as recommended by current guidelines. As low- and medium-risk chest pain patients are so common, the current recommendations contribute to crowding of emergency departments, chest pain and clinical decision units, as well as treadmill labs, not to mention much patient inconvenience and stress, with little to no apparent benefit. Our results suggest that there may be no benefit to early stress testing and resources could be used more efficiently. The difficulty of obtaining guideline-concordant 72-hour stress testing on an outpatient basis, even under ideal health system conditions, and the unclear benefit of hospital-based evaluation, in combination with these low rates of objective adverse events, may warrant reassessment of the ACC/AHA guidelines.

Further, our results demonstrate that patient-level factors did not contribute to 72-hour guideline concordance. Even within an integrated system of insured patients, it is the structural factors of day-of-week and medical center variability that dictate whether a patient is able to receive the test within the guideline-recommended timeframe. This variation by day-of-week and medical center presents an opportunity for future causal studies using instrumental variable analysis.12

Limitations of our study include the retrospective analysis and restriction to a cohort of patients who presented with chest pain, as opposed to other atypical presentations that were evaluated for possible acute coronary syndrome. Additionally, our study excludes patients that were kept in the ED or observed in the hospital to receive a stress test. Our study results are only related to those who an emergency physician stratified by risk and considered safe for discharge and outpatient stress testing. Another limitation is that our study population may not be representative of different types of US health systems. Other regional health care systems may not be as well integrated, and patients may have limited access to primary care and follow-up. Finally, our study design and analyses of MACE rates cannot demonstrate causal inference. This work will inform future analyses (e.g. propensity score, instrumental variables) to assess the causal relationship between early noninvasive testing and 30-day MACE rates.

Conclusion

Patients who are discharged from the ED after an evaluation for possible ACS face a significant challenge in obtaining ACC/AHA guideline-recommended noninvasive cardiac testing within 72 hours. However, in exploratory analyses of this cohort of patients deemed safe for discharge in a well-integrated health care system, there does not appear to be any associated benefit of stress testing within 3 days, nor within 30 days, compared to those who never received testing at all. The lack of benefit of obtaining timely testing, in combination with low rates of objective adverse events, may warrant reassessment of the current guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the patients of Kaiser Permanente for helping us improve care through the use of information collected through our electronic health record systems. We also appreciate the time and dedication of our project management team, Danielle Altman, Visanee Musigdilok, and Marie-Annick Yagapen.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HL134647. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Natsui was supported by NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant (TL1TR001883). Dr. Ferencik was supported by American Heart Association Fellow-to-Faculty Award (13FTF16450001).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Meetings: Preliminary results from this study were presented at a Plenary Session at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine national conference in Indianapolis, IN on May 16, 2018.

Disclosures: There are no conflicts of interest to report for the following authors: SN, ES, YW, RFR, ML, MF, CZ, AAK, MKG, ALS. Author, BCS, was a consultant for Medtronic.

References

- 1.Center for Health Statistics N. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2015 Emergency Department Summary Tables.

- 2.Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, et al. Missed Diagnoses of Acute Cardiac Ischemia in the Emergency Department. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(16): 1163–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004203421603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014; 130(25):e344–e426. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer MC, Mooney RP, Sekera AK. A critical pathway for patients with acute chest pain and low risk for short-term adverse cardiac events: role of outpatient stress testing. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(5): 427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milano P, Carden DL, Jackman KM, et al. Compliance With Outpatient Stress Testing in Low-risk Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department With Chest Pain. Crit Pathways Cardiol A J Evidence-Based Med. 2011;10(1):35–40. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e31820fd9bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Story M, Reynolds B, Bowser M, Xu H, Lyon M. Barriers to outpatient stress testing follow-up for low-risk chest pain patients presenting to an ED chest pain unit. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(5):790–793. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.12.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharp AL, Broder B, Sun BC. Improving Emergency Department Care for Low-Risk Chest Pain. NEJM Catal Care Redesign. 2018;(April 18). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharp AL, Wu Y-L, Shen E, et al. The HEART Score for Suspected Acute Coronary Syndrome in U.S. Emergency Departments. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(15): 1875–1877. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ. A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47(6):626–633. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermann LK, Newman DH, Pleasant WA, et al. Yield of Routine Provocative Cardiac Testing Among Patients in an Emergency Department-Based Chest Pain Unit. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(12):1128. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foy AJ, Liu G, Davidson WR, Sciamanna C, Leslie DL. Comparative Effectiveness of Diagnostic Testing Strategies in Emergency Department Patients With Chest Pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):428. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandhu AT, Heidenreich PA, Bhattacharya J, Bundorf MK. Cardiovascular Testing and Clinical Outcomes in Emergency Department Patients With Chest Pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8): 1175. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safavi KC, Li S-X, Dharmarajan K, et al. Hospital variation in the use of noninvasive cardiac imaging and its association with downstream testing, interventions, and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):546–553. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown MD, Wolf SJ, Byyny R, et al. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Emergency Department Patients With Suspected Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(5):e65–e106. doi: 10.1016/J.ANNEMERGMED.2018.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.