Abstract

Purpose:

This study investigated the relationship between familial residential school system (RSS) exposure and personal child welfare system (CWS) involvement among young people who use drugs (PWUD).

Methods:

Data were obtained from two linked cohorts of PWUD in Vancouver, Canada and restricted to Indigenous participants. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the relationship between three categories of familial RSS exposure (none; grandparent; parent) and CWS involvement. A secondary analysis assessed the likelihood of CWS involvement between non-Indigenous and Indigenous PWUD with no familial RSS exposure.

Results:

Between December 2011 and May 2016, 675 PWUD (age<35) were included in this study, 40% identified as Indigenous. In multivariable analyses, compared to Indigenous participants with no RSS exposure (reference), those with a grandparent in the RSS had a higher likelihood of having been in CWS (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR]=1.34, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.67-2.71), as did those with a parent exposed to RSS (AOR=2.03, 95% CI: 1.03-3.99). In secondary analysis, the odds of CWS involvement was not significantly different between non-Indigenous and Indigenous PWUD with no familial RSS exposure (AOR=0.63, 95% CI: 0.38–1.06).

Conclusions:

We observed a dose-response-type trend between familial RSS exposure and personal CWS involvement, and a non-significant difference in the likelihood of CWS involvement between Indigenous and non-Indigenous PWUD when controlling for RSS exposure. These data demonstrate the intergenerational impact of the RSS on the overrepresentation of Indigenous youth in the CWS. Findings have critical implications for public policy and practice including reconciliation efforts with Indigenous Peoples.

“For someone like me, not learning so many basic life skills that I should have learned, I couldn’t carry forward when I had my own family, so as a result of that, my own family suffered in their own ways. It’s an experience with an intergenerational impact.”(1)

-Robert Joseph, Hereditary Chief of the Gwawaenuk First Nation

Indigenous Peoples1 have suffered the harms of colonization at the hands of what was British North America and now is Canada and the United States for hundreds of years (2, 3). These harms include the forcible displacement from ancestral lands, dismantlement of Indigenous governance structures, introduction of disease (e.g., smallpox, influenza), systemic discrimination, assimilative policies, and physical, biological and cultural genocide (2-5). In Canada, one of the most damaging aspects of this relationship was the historical trauma inflicted by the residential school system (RSS). Beginning in the late 1800s, a system of boarding schools was established across the country as a church-state partnership designed with the purpose to “kill the Indian in the child,” furthering the ultimate goal of assimilation by eliminating the “Indian problem” (6, 7). To this end, Indigenous children were forbidden to speak their native language, engage in spiritual practices, maintain cultural traditions, and were frequently and deliberately placed in schools a considerable distance from their communities, severing family ties (8). Further, due to a combination of inadequate funding, shelter, basic public health, and nutrition, Indigenous children frequently succumbed to preventable diseases while attending a residential school (2, 4, 6). More recently, horrific accounts of sexual, physical and emotional abuse have been documented and a number of former residential school staff have been convicted in for their part in these crimes (2, 6).

By 1920, residential school attendance was legally mandated for all school-aged Indigenous children. During the height of the RSS in the 1930-40s, it is estimated that 20% of the total Indigenous population across Canada, or approximately 90,000-100,000 children, were institutionalized (4). While the majority of residential schools were shut down by the 1950-60s, the last government-funded school closed in Saskatchewan in 1996 (2). The government policies that followed the residential school era continued to harm Indigenous families and communities. During what has been labeled the “Sixties Scoop,” thousands of Indigenous children were apprehended by Canadian child welfare agencies and placed in predominantly non-Indigenous homes – many were sold to wealthy white families in the United States and Europe (9).

Today, many researchers and advocates argue that Canadian child welfare systems (CWS) continue the legacy of residential schools (8-10). Across the country, Indigenous children are vastly overrepresented at every stage of the CWS, from investigations to out-of-home care placements (8, 11, 12). Prior research estimates there are three times as many Indigenous children in government care today than there were at the height of the residential schools (13). For example, in the province of British Columbia where our study is set, Indigenous youth comprised 63% of the total youth in care in 2017, while only accounting for approximately 10% of the youth population (14).

In addition to continued ethnocentric and assimilative policies around child rearing and welfare, potential underlying factors associated with high apprehension rates can be understood as an outcome of historical trauma. Originally conceptualized to explain the negative impacts on subsequent generations of holocaust survivors, intergenerational or historical trauma is increasingly being applied to the atrocities associated with colonization experienced by Indigenous populations in the Americas (3). Intergenerational trauma is defined as the shared collective experiences of sustained and numerous attacks on a group that may accumulate over generations (3, 5, 15, 16). As residential schools cut off Indigenous students from their families, communities, and cultures, and as school staff interacted with students based on a model of control, punishment, and fear – in addition to personal traumas incurred – many survivors experienced difficulties engaging in healthy relationships and healthy parenting with their own children (2). Prior research has found that RSS survivors experience a host of risks associated with diminished parental capacity including, elevated rates of problematic alcohol and substance use, fetal alcohol syndrome, domestic violence, and poorer physical and mental health compared to those who did not attend a residential school (17, 18). Relatedly, research and government data have consistently found that families of lower socioeconomic status are overrepresented in the CWS (19), and that Indigenous children, particularly First Nations children living on reserves, live in poverty at far greater rates than non-Indigenous people in Canada (20).

Parental substance use is a known risk factor for child welfare involvement and is common among all families involved with the CWS (19, 21). Substance use has been previously demonstrated to have an intergenerational effect on offspring of parents who use drugs (21, 22). This is concerning as adolescence is generally regarded as the period of time when risk for initiating substance use is the highest, as well as when substance use increases, peaking in young adulthood (23). Further, adolescence is a critical period for cognitive development as well as the establishment of life-long health behaviours that early substance use may disrupt (23, 24). The present analyses use a study population of younger people who use drugs (PWUD) with high rates of street and CWS involvement. We chose to focus on this study population given the aforementioned links between substance use and adverse childhood experiences (e.g., trauma, abuse, neglect), CWS involvement and residential school attendance.

Addressing the overrepresentation of Indigenous children in the CWS is a critical priority for the health and wellbeing of Indigenous communities (8, 13). It is clear for those with lived experience that intergenerational trauma has led to a host of health and social issues. These factors when considered together with decades of colonial child welfare policies and the erosion of traditional Indigenous kinship structures and parental role modeling have contributed to the disproportionate number of Indigenous children in government care today. However, few quantitative or epidemiological research studies have been conducted in this area and, tragically, certain segments of the Canadian population continue to deny or refuse to acknowledge the links between colonization and present-day disparities (25-27). This lack of recognition hinders reconciliation efforts and possibly undermines progress towards investing in programs that may help reduce the number of Indigenous children in the CWS. In a previous study conducted in the same setting, we observed that Indigenous youth were significantly more likely to have been in the CWS (21); however, we hypothesized that familial residential school exposure may account for this observed association. While the influence of intergenerational trauma associated with the RSS on present-day disparities is complex, we sought to assess whether familial residential school exposure was associated with an increased likelihood of personal involvement with the CWS among a cohort of youth and young adults who use drugs (PWUD) in Vancouver, Canada.

METHODS

Data for this study were collected between December 1, 2011 and May 31, 2016 from two prospective cohorts of PWUD (i.e., the At-Risk Youth Study [ARYS], and the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study [VIDUS]), with harmonized procedures for recruitment, follow-up and data collection in Vancouver, Canada. Study rationale and procedures for ARYS and VIDUS have been described elsewhere in detail (28, 29). In brief, to be eligible, participants must reside in the greater Vancouver region, have used illicit ‘hard’ drugs (e.g., crack, cocaine, heroin, crystal methamphetamine) in the past-30 days and provided written informed consent. Specific inclusion criteria for VIDUS consists of HIV-negative adults (≥18 years) who have injected drugs in the month prior to study enrolment. For ARYS, youth were eligible if they were ‘street-involved,’ defined as being absolutely or temporarily without stable housing or having used a service for street-involved youth in the past-30 days and between the ages of 14-26 at time of enrolment. All participants underwent an interviewer administered questionnaire at baseline and semi-annually thereafter and received a $30 honouraria at each study visit. The questionnaire elicits information on socio-demographics, drug use patterns, and childhood experiences. The University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board has approved both ARYS and VIDUS. Lastly, the Western Aboriginal Harm Reduction Society (WAHRS), a community group of Indigenous PWUD in Vancouver, has been consulted and provided support for our aims in the present study, as well as the residential school measures being added to the study instrument prior to this study. WAHRS board members and an Indigenous youth with lived experience of the CWS were consulted throughout the study process and co-authored the manuscript (KS, MT, LL). This facilitated a deeper understanding of living with historical trauma through sharing of personal stories, with the intention of supporting culturally appropriate interpretations and dissemination of findings.

The present study combined data from ARYS and young adults in the VIDUS cohort (age<35 at baseline) to examine the potential relationship between familial exposure to the RSS and subsequent CWS involvement. We conducted two analyses, both assessing the likelihood of CWS involvement. The primary outcome of interest was having a history of being in the CWS defined as, having ever been placed in an orphanage, foster home, group home, being a ward of the state, or away from parents for longer than a month (not including vacations) before turning the legal age of majority. The primary analysis was restricted to participants who self-identified as being of Indigenous ancestry, defined in this context as First Nations, Métis, Aboriginal or Inuit. The primary independent variable of interest was familial residential school exposure defined as having a parent or grandparent that attended a residential school. This measure was categorized into three mutually exclusive categories: no immediate familial residential school exposure (reference category); grandparental exposure (but no parental exposure) to a residential school; parental exposure or parental and grandparental exposure to a residential school. The objective of the main analysis was to assess the intergenerational influence of the RSS on the likelihood for personal CWS involvement among younger Indigenous PWUD controlling for potential confounders.

For the secondary analysis, we sought to assess whether Indigenous PWUD were still at an increased risk of CWS involvement if they did not have immediate familial residential school exposure, defined as not having either a parent and/or a grandparent that attended a residential school. To do this we compared the likelihood of CWS involvement between non-Indigenous participants and Indigenous participants who reported no immediate familial residential school exposure.

Possible confounders included: sex (female vs. male), age (per year older), high school incompletion (yes vs. no), ever incarcerated (yes vs. no), childhood maltreatment (severe/moderate vs. low/none), year of recruitment (per year longer), and cohort (VIDUS vs. ARYS). Childhood maltreatment was defined using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (30), a validated 25-item measure to detect various types of childhood neglect and abuse previously used among street-involved and drug using populations (31). We first stratified descriptive characteristics by history of CWS involvement (yes vs. no). We then evaluated the bivariable association between each explanatory variable and the outcome of interest using logistic regression. For both the primary and sub-analysis, a fixed multivariable logistic regression model was employed. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC). All p-values are two sided.

RESULTS

Over our study period, 675 PWUD (age<35) were enrolled into VIDUS and ARYS and eligible for these analyses. Among this sample, 259 (38.4%) were female and the median age at baseline was 23.3 (Interquartile range [IQR]: 21.1–27.4) years. Among the 267 (39.6%) participants who identified as being of Indigenous ancestry, 179 (67.0%) were First Nations, 29 (10.7%) were Metis, and 9 (3.4%) identified as Aboriginal (no participants identified as Inuit). Among Indigenous participants, 90 (18.1%) reported no immediate familial residential school exposure (median age = 23.7, IQR: 21.1–29.6), 73 (27.3%) reported a grandparent that attended a residential school (but no parent) (median age = 22.5, IQR: 21.1–24.7), and 104 (39.0%) reported having either a parent or both a parent and a grandparent that attended a residential school (median age = 24.7, IQR: 22.4–30.0).

The descriptive statistics, bivariable and multivariable findings for the primary analysis are presented in Table 1. In multivariable analysis, adjusting for sex, age, high school completion, incarceration, childhood maltreatment, year of recruitment, and cohort, compared to Indigenous participants who reported no immediate familial residential school exposure, those who reported having a grandparent that attended a residential school had a non-significant increase in the odds of personal CWS involvement (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.34, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.67–2.71). However, Indigenous participants who reported having a grandparent or both a parent and grandparent that attended a residential school were significantly more likely to have been personally involved with the CWS (AOR = 2.03; 95% CI: 1.03–3.99).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses assessing the impact of familial exposure to the residential school system (RSS) on personal involvement with the child welfare system among younger Indigenous PWUD (age<35) in Vancouver, Canada (n=267).

| Child welfare exposure |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Yes n = 178, n (%) |

No n = 89, n (%) |

Odds Ratio, (95% CIa) |

p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio, (95% CI) |

p-value |

| Familial RSSb exposure | ||||||

| No RSS exposure | 53 (58.9) | 37 (41.1) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Grandparent RSS exposure | 48 (65.8) | 25 (34.2) | 1.34 (0.71 – 2.54) | 0.370 | 1.34 (0.67 – 2.71) | 0.410 |

| Parent or parent and grandparent RSS exposure | 77 (74.0) | 27 (26.0) | 1.99 (1.09 – 3.65) | 0.026 | 2.03 (1.03 – 3.99) | 0.040 |

| Age (per year older) | ||||||

| Median | 23.6 | 24.0 | 0.99 (0.94 – 1.05) | 0.811 | 1.04 (0.94 – 1.15) | 0.459 |

| IQR c | (21.2 – 28.3) | (22.0 – 27.4) | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 85 (66.4) | 43 (33.6) | 0.98 (0.59 – 1.63) | 0.931 | 1.09 (0.61 – 1.96) | 0.771 |

| Male | 93 (66.9) | 46 (33.1) | Reference | Reference | ||

| High school completion | ||||||

| Yes | 55 (63.2) | 32 (46.8) | 0.80 (0.47 – 1.37) | 0.424 | 0.78 (0.44 – 1.41) | 0.418 |

| No | 122 (68.2) | 57 (31.8) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Incarceration | ||||||

| Yes | 139 (68.4) | 64 (31.6) | 1.48 (0.90 – 2.42) | 0.121 | 1.51 (0.83 – 2.75) | 0.177 |

| No | 36 (59.0) | 25 (61.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Childhood maltreatment | ||||||

| Yes | 125 (68.3) | 58 (31.7) | 1.16 (0.62 – 2.18) | 0.633 | 1.29 (0.65 – 2.54) | 0.466 |

| No | 37 (64.9) | 20 (35.1) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Year of recruitment | ||||||

| Median | 2011 | 2012 | 0.99 (0.93 – 1.07) | 0.839 | 1.02 (0.94 – 1.11) | 0.683 |

| IQR | (2007-2014) | (2008-2014) | ||||

| Cohort | ||||||

| VIDUS | 68 (64.2) | 38 (35.8) | 0.83 (0.49 – 1.39) | 0.479 | 0.54 (0.20 – 1.45) | 0.223 |

| ARYS | 110 (68.3) | 51 (31.7) | Reference | Reference | ||

Note:

CI = Confidence Interval;

RSS = Residential School Exposure;

IQR = Interquartile Range; PWUD = people who use drugs

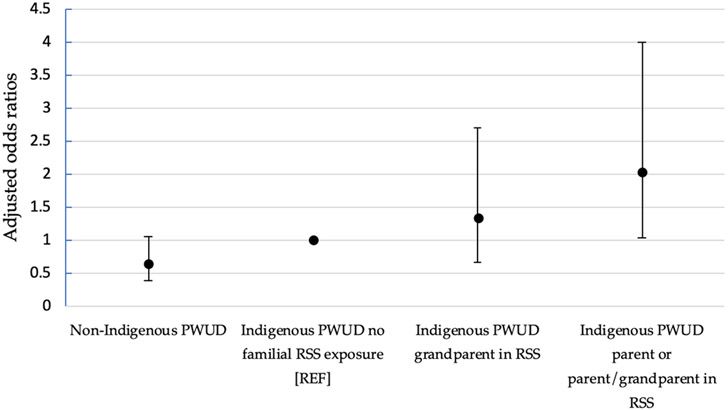

In the secondary analysis (Table 2), there was not a detectable difference between Indigenous participants with no immediate familial residential school exposure and non-Indigenous participants with respect to the likelihood of CWS involvement (AOR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.38 – 1.06). The point estimates and confidence intervals for both analyses are combined in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Secondary analysis assessing the relationship between ethnicity and involvement with the child welfare system among younger PWUD (age<35) in Vancouver, Canada (n=498).

| Child welfare exposure |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Yes n = 241, n (%) |

No n = 257, n (%) |

Odds Ratio, (95% CIa) |

p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio, (95% CI) |

p-value |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Indigenous | 188 (46.1) | 220 (53.9) | 0.59 (0.38 – 0.94) | 0.029 | 0.63 (0.38 – 1.06) | 0.083 |

| Indigenous with no immediate familial RSSb exposure | 53 (58.9) | 37 (41.1) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Age (per year older) | ||||||

| Median | 22.7 | 23.4 | 0.98 (0.94 – 1.01) | 0.231 | 0.92 (0.85 – 1.00) | 0.045 |

| IQRc | (20.5 – 27.3) | (21.2 – 28.0) | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 95 (54.6) | 79 (45.4) | 1.47 (1.01 – 2.12) | 0.043 | 1.27 (0.82 – 1.98) | 0.282 |

| Male | 146 (45.1) | 178 (54.9) | Reference | Reference | ||

| High school completion | ||||||

| Yes | 78 (38.6) | 124 (61.4) | 0.50 (0.34 – 0.72) | <0.001 | 0.59 (0.39 – 0.89) | 0.013 |

| No | 161 (55.9) | 127 (44.1) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Incarceration | ||||||

| Yes | 173 (55.1) | 141 (44.9) | 2.12 (1.46 – 3.09) | <0.001 | 2.74 (1.72 – 4.37) | <0.001 |

| No | 66 (36.7) | 114 (63.3) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Childhood maltreatment | ||||||

| Yes | 166 (51.1) | 159 (48.9) | 1.68 (1.08 – 2.60) | 0.021 | 1.72 (1.08 – 2.76) | 0.023 |

| No | 43 (38.4) | 69 (61.6) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Year of recruitment | ||||||

| Median | 2013 | 2013 | 0.97 (0.93 – 1.02) | 0.251 | 1.00 (0.95 – 1.06) | 0.959 |

| IQR | (2007-2014) | (2008-2015) | ||||

| Cohort | ||||||

| VIDUS | 81 (50.3) | 80 (49.7) | 1.12 (0.77 – 1.63) | 0.554 | 2.03 (0.91 – 4.51) | 0.083 |

| ARYS | 160 (47.5) | 177 (52.5) | Reference | Reference | ||

Note:

CI = Confidence Interval;

RSS = Residential School Exposure;

IQR = Interquartile Range; PWUD = people who use drugs

Figure 1.

Primary and sub-analysis combined, depicting point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for child welfare system involvement among younger people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada (n=675). Note: Reference group for both analyses is Indigenous PWUD with no reported immediate familial RSS exposure (n=90).

DISCUSSION

We observed a dose-response-type trend between familial residential school exposure and having been personally involved with the CWS among younger Indigenous PWUD. Participants who had either a parent (or grandparent and parent) that attended a residential school, were found to have more than two times the odds of having been in government care. Those with a grandparent (but no parent) that attended a residential school also had increased odds of being in care, however, this association did not meet conventional statistical significance. Further, we observed a non-significant difference in the likelihood of being CWS involvement between Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants when controlling for familial residential school exposure among our sample. This is rather remarkable given that previous analyses in our study setting documented that Indigenous street-involved youth had over two times the odds of having been in government care compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts, when familial residential school exposure was not controlled for (21).

As noted previously, Indigenous children and families are overrepresented at every stage of the child welfare process. The Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Maltreatment, the first nationally representative study to collect data on CWS involved youth in Canada, found that Indigenous families were 4.2 times more likely to be investigated for child maltreatment and that substantiated maltreatment cases were twice as likely to result in out-of-home placements compared to non-Indigenous cases (8, 12). Moreover, although all identified categories of maltreatment (e.g., neglect, emotional maltreatment, physical abuse, sexual abuse) were disproportionately higher among Indigenous versus non-Indigenous cases, the ratio for neglect was the most extreme (6.0 times higher) (12). Charges of neglect are frequently indicators of poverty (e.g., housing instability, food insecurity, not attending school), suggesting that Indigenous families are in need of support and resources more than the CWS. This is supported in the literature, as previous analyses of data from nearly 5,000 Indigenous children across the country found that parental residential school attendance was associated with lower socioeconomic status, living in a larger household, food insecurity, and poor educational outcomes (32).

These findings contribute empirical evidence to the lived knowledge that the intergenerational trauma associated with the RSS continues to negatively impact Indigenous Peoples today. Emerging research has begun to investigate the intergenerational impact of the RSS on the health and wellbeing of subsequent generations of Indigenous youth. Preliminary research and survey data from nationally representative samples of Indigenous Peoples across Canada reported that youth and young adult-children of RSS survivors experience increased negative physical and mental health issues, including higher rates of suicidal ideation and attempts compared to individuals without a parent that attended a residential school (15, 17, 33, 34). However, only one previous study that we know of assessed the relationship between familial residential school exposure and CWS involvement. Among a cohort of Indigenous PWUD across B.C., having a parent that attended a residential school was found to be a significant correlate of having been placed in care (35).

In general, child welfare systems have lacked a systematic approach to addressing trauma despite overwhelming rates of complex trauma among youth in care (36). However, there is growing recognition that trauma-informed care frameworks should and are increasingly being integrated within child welfare practice (36). Our findings add to this emerging evidence-base by supporting the need for trauma-informed care when working with Indigenous families involved with the CWS, but also highlight the importance of culturally appropriate trauma-informed approaches and training for child welfare workers (2). Some progress has been made with regard to the overrepresentation of Indigenous youth in the CWS. The 1990s saw an influx of Indigenous child welfare agencies on- and off-reserve assume responsibility for delivering services to Indigenous families (10). However, these efforts have been hampered by unstable, inequitable and inadequate funding structures, restrictive and culturally inappropriate child welfare policies and laws, and a lack of physical and personnel resources (10, 13). Some amendments to child welfare statutes have been legislated across the country including, band notification of placements, prioritization of kinship care, preservation of cultural connections, and Indigenous involvement in case management and service delivery (10). Yet, legislation remains unstandardized across jurisdictions and serious concerns about Indigenous child welfare services remain, particularly, that they are vastly underfunded, underresourced, and continue to operate on colonial premises and laws (2, 10, 13).

In 2008, the Government of Canada established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) with the mandate to provide a safe platform for survivor accounts of residential school experiences, create a complete historical record of the RSS and its legacy, educate Settler Canadians and promote awareness, and to develop a set of recommendations for the government to move towards reconciliation (37). Reconciliation as defined by the TRC is establishing and sustaining a mutually respectful relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples through the awareness, acknowledgement and atonement for the harms inflicted by the RSS and using this knowledge to change beliefs and behaviour (2). Among the TRC’s 94 calls to action, addressing the overrepresentation of Indigenous youth and families involved with the CWS is the first theme identified in moving towards reconciliation and includes investing in upstream interventions to keep vulnerable families together (e.g., culturally appropriate parenting programs, addressing the determinants of child neglect), requiring the CWS to embed culturally appropriate and historically informed policies and practices, legislating national Indigenous child welfare standards and tracking, and returning control over child welfare to Indigenous communities and organizations (37).

Although not the primary focus of this paper, some notable differences were observed between the two analyses. For example, the associations between CWS involvement and childhood maltreatment, high school completion and incarceration did not meet conventional statistical significance when restricted to Indigenous PWUD (Table 1), but statistically significant associations were observed for those three variables and the outcome of interest in the secondary analysis among non-Indigenous PWUD and Indigenous PWUD with no familial residential school exposure (Table 2). This is unexpected as having a history of childhood maltreatment, poor educational outcomes, and involvement with the criminal justice system are common among youth in government care (38) – indeed, child maltreatment is strongly associated with CWS involvement (19). While our data cannot elucidate these non-significant relationships, as previously mentioned, Indigenous families are frequently involved with the CWS due to charges of neglect, which has been correlated with poverty (12). Given that Indigenous children experience elevated rates of poverty in Canada (20), it is possible that low familial socioeconomic status, and not child maltreatment, precipitated CWS involvement among our sample. This may have scored lowly on the diagnostic instrument measuring child maltreatment (i.e., Childhood Trauma Questionnaire). Further research focused on this issue is warranted.

This study is not without limitations. First, as with all observational research, our sample is not a random sample and therefore many not generalize to all populations of Indigenous people with familial residential school exposure or people who use drugs. Second, data were collected using self-reported interviews and are thus vulnerable to response bias. Additionally, due to the relatively small sample size of Indigenous participants without immediate familial residential school exposure, there is the possibility that the non-significant findings in the secondary analysis were due to random error and further research with larger samples is warranted. However, it is plausible that some of our sample may have been misclassified as having no immediate familial residential school exposure due to the immense shame commonly experienced by survivors resulting in participants unknowingly underreporting their family’s status and our estimates being attenuated.

In closing, the current study provides empirical evidence that colonial practices continue to affect present-day health and social disparities experienced by Indigenous families. It is important to note that our data does not provide direction on how to best address the ongoing impacts of the RSS. Documenting these connections provides a foundation from which to advocate for increased support and investment in Indigenous-led approaches to address the intergenerational trauma associated with colonial child welfare policy. Furthermore, our findings point to the need to address upstream issues that perpetuate the overrepresentation of Indigenous families in the CWS. Poverty, addictions, family violence, housing, sanitation, food security, and inequitable access to education and other resources remain serious impediments to progress in this realm. As Canada faces its colonial history, the public and policymakers can no longer ignore a growing body of evidence regarding the impacts of the RSS and continued assimilative child welfare policies on the health and wellbeing of Indigenous people today.

Implications and contribution:

This study documents a dose-response type trend between familial exposure to Canada’s residential school system and personal involvement in the child welfare system among young people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff. The authors would specifically like to thank Carly Ho, Jennifer Matthews, Peter Vann, Steve Kain, and Marina Abramishvili for their research and administrative assistance. The authors respectfully acknowledge that this study was undertaken on the unceded territories of the xwməθkwəýəm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Salílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.

Role of funding: The study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (U01DA038886). Dr. Kora DeBeck is supported by a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR)/St. Paul’s Hospital-Providence Health Care Career Scholar Award. Dr. Kanna Hayashi is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) New Investigator Award (MSH-141971) and MSFHR Scholar Award. Brittany Barker is supported by a CIHR Doctoral Award. Funding sources had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

‘Indigenous’ in the Canadian context refers to all status and non-status ‘Indians’ or First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. However, it is important to note that by homogenizing various groups and communities within a pan Indigenous population we may be replicating colonial discourse and reproducing harms (Alfred, 2009). Our use of a singular term here is for ease of interpretation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sherlock T Healing the past is possible through dialogue, B.C. Chief says The Vancouver Sun. Vancouver, Canada: The Vancouver Sun, Sept 3 2016. http://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/healing-the-past-is-possible-through-dialogue-chief-says (accessed 12 Jan 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg, Manitoba: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; 2015. Available at: http://www.bishop-accountability.org/reports/TRC/2015_06_02_Truth_and_Reconciliation_Executive_Summary_Honoring_the_Truth.pdf Accessed May 31, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brave Heart MYH, DeBruyn LM. The American Indian holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaska Native MentalHealth Research 1998;8:56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milloy JS. A national crime: The Canadian government and the residential school system, 1879 to 1986. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans-Campbell T Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2008;23:316–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 1: Looking forward, looking back Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP). Ottawa, Canada: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nock D A victorian missionary and Canadian Indian policy: Cultural synthesis vs cultural replacement: Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trocme N, Knoke D, Blackstock C. Pathways to the overrepresentation of aboriginal children in Canada's child welfare system. Soc Serv Rev 2004;78:577–600. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKenzie HA, Varcoe C, Browne AJ, et al. Disrupting the continuities among residential schools, the Sixties Scoop, and child welfare: An analysis of colonial and neocolonial discourses. International Indigenous Policy Journal 2016;7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinha V, Kozlowski A. The structure of Aboriginal child welfare in Canada. International Indigenous Policy Journal 2013;4:2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fallon B, Chabot M, Fluke J, et al. Placement decisions and disparities among Aboriginal children: Further analysis of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect part A: Comparisons of the 1998 and 2003 surveys. Child Abuse & Neglect 2013;37:47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinha V, Trocmé N, Fallon B, et al. Understanding the investigation-stage overrepresentation of First Nations children in the child welfare system: An analysis of the First Nations component of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect 2008. Child Abuse & Neglect 2013;37:821–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blackstock C, Trocmé N. Community-based child welfare for Aboriginal children: Supporting resilience through structural change. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand 2005;24:12–33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.B.C. Ministry of Children and Family Development. Children in care. Available at:https://mcfd.gov.bc.ca/reporting/services/child-protection/permanency-for-children-and-youth/performance-indicators/children-in-care Accessed Sept 23 2018.

- 15.Bombay A, Matheson K, Anisman H. The intergenerational effects of Indian residential schools: Implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcultural Psychiatry 2014;51:320–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brave Heart MYH, Chase J, Elkins J, et al. Historical trauma among Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research, and clinical considerations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 2011;43:282–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elias B, Mignone J, Hall M, et al. Trauma and suicide behaviour histories among a Canadian Indigenous population: An empirical exploration of the potential role of Canada's residential school system. Social Science & Medicine 2012;74:1560–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross A, Dion J, Cantinotti M, et al. Impact of residential schooling and of child abuse on substance use problem in Indigenous Peoples. Addictive Behaviors 2015;51:184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect - 2008: Major findings. Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2010. Available from: http://cwrp.ca/sites/default/files/publications/en/CIS-2008-rprt-eng.pdf Accessed June 12 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macdonald D, Wilson D. Shameful neglect: Indigenous child poverty in Canada. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2016. Available from: https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/shameful-neglect Accessed June 14, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barker B, Kerr T, Alfred G, et al. High prevalence of exposure to the child welfare system among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting: implications for policy and practice. BMC Public Health 2014;14:197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith DK, Johnson AB, Pears KC, et al. Child maltreatment and foster care: Unpacking the effects of prenatal and postnatal parental substance use. Child Maltreatment 2007;12:150–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Squeglia LM, Gray KM. Alcohol and drug use and the developing brain. Current Psychiatry Reports 2016;18:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulenberg JE, Sameroff AJ, Cicchetti D. The transition to adulthood as a critical juncture in the course of psychopathology and mental health. Development and Psychopathology 2004;16:799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirkup K Senator Beyak says ‘silent majority’ supports her on residential schools The Globe and Mail. Ottawa, Canada: The Globe and Mail Inc; April 6 2017. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/senator-beyak-sayssilent-majority-supports-her-on-residential-schools/article34615193/ (accessed 2 Apr 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Black C Conrad Black: Aboriginals deserve a fair deal, but enough with us hating ourselves National Post. Toronto, Canada: National Post, Postmedia Network Inc; August 4 2017. http://nationalpost.com/news/canada/conrad-black-aboriginals-deserve-a-fair-deal-but-enough-with-us-hating-ourselves (accessed 4 Apr 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Widdowson F, Howard A. Disrobing the aboriginal industry: the deception behind indigenous cultural preservation. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PA, et al. Barriers to use of free antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users. JAMA 1998;280:547–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood Stoltz J-A, Montaner J, et al. Evaluating methamphetamine use and risks of injection initiation among street youth: the ARYS study. Harm Reduction Journal 2006;3:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect 2003;27:169–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barker B, Kerr T, Dong H, et al. High school incompletion and childhood maltreatment among street-involved young people in Vancouver, Canada. Health & Social Care in the Community 2015; 25:378–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bougie E, Senecal S, Indian, et al. Registered Indian children's school success and intergenerational effects of residential schooling in Canada. The International Indigenous Policy Journal 2010;1:5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hackett C, Feeny D, Tompa E. Canada's residential school system: Measuring the intergenerational impact of familial attendance on health and mental health outcomes. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2016;70:1096–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McQuaid RJ, Bombay A, McInnis OA, et al. Suicide ideation and attempts among First Nations Peoples living on-reserve in Canada: The intergenerational and cumulative effects of Indian Residential Schools. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2017;62:422–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.For the Cedar Project P, Adam FC, Wayne MC, et al. The Cedar Project: Negative health outcomes associated with involvement in the child welfare system among young Indigenous people who use injection and non-injection drugs in two Canadian cities. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2015;106:e265–e270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tullberg E, Kerker B, Muradwij N, et al. The Atlas Project: Integrating trauma-informed practice into child welfare and mental health settings. Child Welfare 2017;95:107–125. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada:Calls to Action. Available from: https://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf Accessed Dec 23 2018.

- 38.Courtney ME, Dworsky A. Early outcomes for young adults transitioning from out-of-home care in the USA. Child & Family Social Work 2006;11:209–219. [Google Scholar]