Abstract

Klebsiella variicola is considered an emerging pathogen in humans and has been described in different environments. K. variicola belongs to Klebsiella pneumoniae complex, which has expanded the taxonomic classification and hindered epidemiological and evolutionary studies. The present work describes the molecular epidemiology of K. variicola based on MultiLocus Sequence Typing (MLST) developed for this purpose. In total, 226 genomes obtained from public data bases and 28 isolates were evaluated, which were mainly obtained from humans, followed by plants, various animals, the environment and insects. A total 166 distinct sequence types (STs) were identified, with 39 STs comprising at least two isolates. The molecular epidemiology of K. variicola showed a global distribution for some STs was observed, and in some cases, isolates obtained from different sources belong to the same ST. Several examples of isolates corresponding to kingdom-crossing bacteria from plants to humans were identified, establishing this as a possible route of transmission. goeBURST analysis identified Clonal Complex 1 (CC1) as the clone with the greatest distribution. Whole-genome sequencing of K. variicola isolates revealed extended-spectrum β-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing strains with an increase in pathogenicity. MLST of K. variicola is a strong molecular epidemiological tool that allows following the evolution of this bacterial species obtained from different environments.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Molecular biology, Bacteria, Bacterial genomics

Introduction

The Klebsiella genus, a member of the family Enterobacteriaceae, comprises species found in diverse environmental niches. In fact, using phylogenetic reconstruction methods, Klebsiella pneumoniae has been divided into five distinct species. Klebsiella variicola was first described in 20041, followed by the identification Klebsiella quasipneumoniae in 2014 (with two subspecies; K. quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae and K. quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae)2, Klebsiella quasivariicola (which remains to be validated) in 20173. Finally in 2019 Klebsiella africanensis a new bacterial species and a subspecies of K. variicola; named, Klebsiella variicola subsp. tropicalensis were described4. The description of these new bacterial species has expanded the taxonomic classification of the genus Klebsiella, which are described as the Klebsiella pneumoniae complex5. Since K. variicola was described several international reports have discussed its importance6; indeed, it is considered an emerging pathogen in humans7. Similar to other Klebsiella species, K. variicola is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, nonspore-forming, nonmotile rod-shaped bacteria that forms circular, convex, and smooth colonies8. K. variicola was initially identified as an endophyte in plants and as a pathogen in humans1. In addition, K. variicola is considered a symbiont in insects, a pathogen in animals and plants. Moreover, K. variicola has been identified in several environmental sources6,9–11. As a human pathogen, K. variicola has been isolated from diverse clinical samples, including the blood, tracheal aspirates, several types of secretions, the respiratory and urinary tract infections, and surgical wounds7. The estimated prevalence of K. variicola is highly variable: initially, a prevalence of 8% was reported1, which has varied over time from 1.8% to 24.4% in clinical settings12–14. The highest percentage reported to date is 24.4%, which were obtained from bloodstream infections in a University Hospital in Solna, Sweden14. The prevalence of the species complex is variable, mainly due to misclassification problems13.

Members of the K. pneumoniae complex share biochemical and phenotypic features. This has led to misclassification by conventional methods and several cases of K. variicola misidentified as K. pneumoniae and in a few cases as K. quasipneumoniae; K. quasipneumoniae has also been misidentified as K. variicola15,16. K. pneumoniae being the most prevalent species within the complex4,13,17, however, regarding urinary tract infections, K. variicola has been isolated more frequently unlike K. pnuemoniae and K. quasipneumoniae18.

Phylogenetic analysis of the Klebsiella genus, the rpoB gene has been recommended for the proper differentiation of this genus19, even though both the 16S rRNA and rpoB genes have been used for this purpose14,20. The K. variicola strain DX120E was identified using these genes, with rpoB showing a higher level of accuracy21. As correct identification of K. variicola using phylogenetic analysis requires time and trained personnel, thus, several biochemical and basic molecular methods have been explored. The biochemical method using adonitol was not effective, generating false positives22. Nonetheless, several PCR methods have been developed to differentiate certain species of the Klebsiella genus12,23–25. In addition, the use of Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry to identify microorganisms has frequently been reported26. Despite initial difficulty in differentiating among members of this genus13,23, the MALDI-TOF approach has been recently optimized, particularly for the K. pneumoniae complex5.

Using PCR screening, phylogenetic analyses and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) methods, K. variicola has recently been identified in diverse niches with clinical and environmental importance6,7,15. These efforts to identify and characterize a significant number of K. variicola isolates have prompted studies of their molecular characterization and epidemiology. The present study describes the molecular epidemiology of K. variicola using Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST), developed for this purpose. This study identified broad dissemination of K. variicola isolates obtained from different regions of the world and a considerable number of ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing isolates were identified. Likewise, a possible pandemic clone was identified and the notion of kingdom-crossing bacteria from plants to humans, establishing this as a route of transmission for K. variicola.

Results and Discussion

The K. variicola genomes were acquired from public databases, which were collected from various sources in several countries of the five continents. The isolates include from plants, insects, the environment, animals, and a significant number of isolates were obtained from human samples (Supplementary Dataset). Based on 33 K. variicola genomes, the AMPHORA program identified a set of 31 phylogenetic marker genes. Among these genes, rpoB, phoE, nifH, mdh, and infB were previously considered for phylogenetic analysis in K. variicola1, and six genes (phoE, tonB, rpoB, mdh, infB, and gapA) are included in the K. pneumoniae MLST27. In addition, concatenation of fusA, gapA, gyrA, leuS and rpoB has been proposed for the proper phylogenetic differentiation of K. pneumoniae, K. variicola and K. quasipneumoniae2. The genes gyrA, nifH and tonB were eliminate due to they may be subjected to selection bias either by the use of antimicrobial agents28, nitrogen fixation1,29,30 or binding and transport of ferric chelates31, respectively. Finally, leuS (leucyl-tRNA synthetase), pgi (phosphoglucose isomerase), pgk (phosphoglycerate kinase), phoE (phosphoporine E), pyrG (CTP synthase), rpoB (β-subunit of RNA polymerase B) and fusA (elongation factor G) were selected for K. variicola MLST scheme (Table 1) (http://mlstkv.insp.mx) and for the assignation of sequence types (ST) (Supplementary Dataset). Of note, the pyrG (CTP synthase class I) gene is not present in K. pneumoniae genomes, which was verified using a BLASTn genome search and confirmed by PCR of several K. pneumoniae clinical isolates in our collection (data not shown). The primer sequences, amplified fragments, number of alleles, nucleotide diversity and polymorphic sites of each of the seven genes are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of genes, primers, PCR-conditions, nucleotide diversity and polymorphic sites for the K. variicola MLST scheme.

| Locus | Function | Primer name | Primer sequence | Temp (°C) | Size (bp) | No. of alleles | Nucleotide diversity | Polymorphic sites (nonsynonymous substitutions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| leuS | Leucyl-tRNA synthetase | leuSKv-F | CGAACAGGTTATCGACGGCT | 63 | 594 | 48 | 0.012462 | 48 (8) |

| leuSKv-R | CAAAGGTGTCGGTTTCACGC | |||||||

| pgi | Phosphoglucose isomerase | pgiKv-F | AAAGAGACCGATCTGGCAGG | 60 | 600 | 42 | 0.016425 | 49 (6) |

| pgiKv-R | ACCAGATACCGATCAGCGCC | |||||||

| pgk | Phosphoglycerate kinase | pgkKv-F | TCGTGATGGATGCTTTCGGT | 63 | 444 | 26 | 0.012647 | 33 (10) |

| pgkKv-R | AGATTTTGTCAGCGATGCCG | |||||||

| phoE | Phosphoporine E | phoEKv-F | CTGTACGACGTGGAAGCCTG | 63 | 453 | 54 | 0.018569 | 46 (10) |

| phoEKv-R | CCACGAAGGCGTTCATGTTT | |||||||

| pyrG | CTP synthase | pyrGKv-F | CCGATCGCTATGGTCGCTG | 60 | 522 | 60 | 0.011535 | 48 (22) |

| pyrGKv-R | CGGGACATCAGTTCCGGGT | |||||||

| rpoB | β-subunit of RNA polymerase B | rpoBKv-F | GCCAGCTGTCCCAGTTTATG | 60 | 513 | 25 | 0.014945 | 38 (3) |

| rpoBKv-R | GAACGGTACCGCCACGTTTA | |||||||

| fusA | Elongation factor G | fusAKv-F | CGAAAACCAAAGCTGACCAGG | 62 | 561 | 15 | 0.007130 | 23 (4) |

| fusAKv-R | CATGGTGTATGATGCACGACCT |

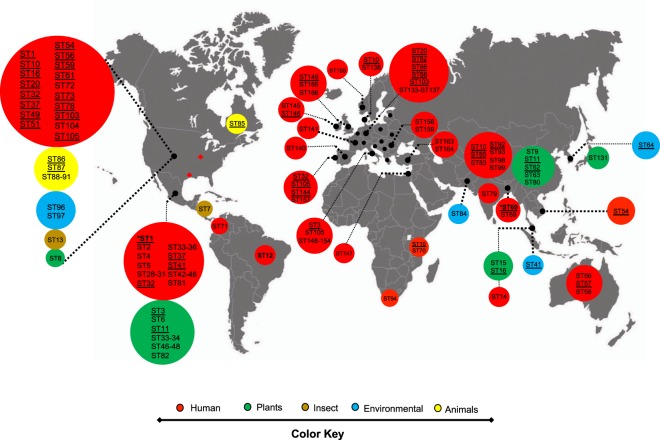

Considering K. variicola isolate 801 obtained from a pediatric outbreak in Mexico32 as ST1 (Supplementary Dataset), and the MLST was applied arbitrarily to K. variicola genomes and isolates include in the study. A total of 166 distinct sequence types (STs) were identified among 254 K. variicola genomes and isolates obtained from different sources, such as humans, plants, insects, the environment and animals. From 166 STs, 39 STs were shared by at least two isolates (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Dataset).

Figure 1.

Molecular epidemiology of K. variicola isolates. The map shows the localization of each ST. The underlined ST corresponds to ST with two or more isolates. The major ST corresponds to genomes described in the USA, Mexico, Germany and China. The origin of the isolates is shown in color codes. The ST market with asterisks corresponds to K. variicola outbreaks. The WGS projects of Klebsiella in the USA are marked with a diamond, corresponding to Texas and Missouri. The black circles in Europe correspond to countries described with a single or two ST (ST underline), as: Greece (ST86), Austria ST125, Belgium (ST132), Estonia (ST139), Croatia (ST142 and ST143), Hungary (ST144), Poland (ST156), Serbia (ST160) and Slovenia (ST161 and ST162).

The global distribution of STs is shown in Fig. 1. The major number of isolates assigned to an ST were from the USA, followed by Mexico, China and Europe (mainly Germany). In the case of the USA, numerous isolates with the same ST were also identified in other regions of the world (Supplementary Dataset). In particular, Klebsiella WGS projects have been performed in the USA, the first was carried out by the Houston Methodist Hospital, Texas13 and the second from the Barnes-Jewish Hospital microbiology laboratory in Missouri18. In both cases, numerous K. variicola isolates were identified, with ST49, ST51, ST73, ST75 and ST77 described in both works (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Dataset).

With respect to Mexico, ST1 corresponds to the first pediatric outbreak of K. variicola32 and other isolates obtained from the USA (WUSM_KV_09)18. In addition, this country contributed the most isolates obtained from different plants (Fig. 1). Overall, human isolates are heterogeneous regarding STs, and only ST32 was identified for two human isolates. Nevertheless, the ST37 and ST41 contains isolates from Mexico, USA and Singapore. In China, isolates from both humans and plants have been described, with ST65 and ST92 corresponding to human isolates described in different reports (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Dataset). The BioProject-PRJEB10018 includes Klebsiella isolates from European countries and identified numerous K. variicola human isolates. These isolates showed heterogeneous STs, with only ST144 (Hungary and Portugal) and ST146 (Ireland and United Kingdom) having the same ST. However, countries in different regions of the world harbor the same STs (ST3, -20, -32, -37, -68, -77, -86, -105 and -125) of isolates described in Europe.

In particular, some STs are highlighted, such as ST10 identified in Denmark, China, Tanzania and the USA. ST11 isolates obtained from plants originate from Mexico and China. Nine human isolates obtained from Germany, Belgium and the USA were identified as ST2018, and ST56 and ST57 were found on distant continents such as North America, Europe and Australia, all from human samples. ST60 corresponds to the second pediatric outbreak of K. variicola described in Bangladesh33 and ST64 to K. variicola obtained from the environment in South Korea10.

Interestingly, three cases of kingdom-crossing bacteria (KCB) were identified by MLST. ST3 was identified in a plant (banana roots) isolate in Mexico and human isolates from Italy and Serbia. ST16 was identified in isolates obtained from a chili plant in Malaysia and humans in the USA. ST62 corresponds to a well-characterized K. variicola D5A isolate obtained from plants in China34 and ID_24 isolates obtained from humans in Germany. The proposal of KCB from plants to humans, which may indicate a process of transfer known as phytonosis, has been described previously29. K. variicola clinical isolate X39 is considered a KCB because it contains genes involved in plant colonization, nitrogen fixation, and defense against oxidative stress; this isolate is also considered an endophytic bacterium based on its capacity to colonize maize35.

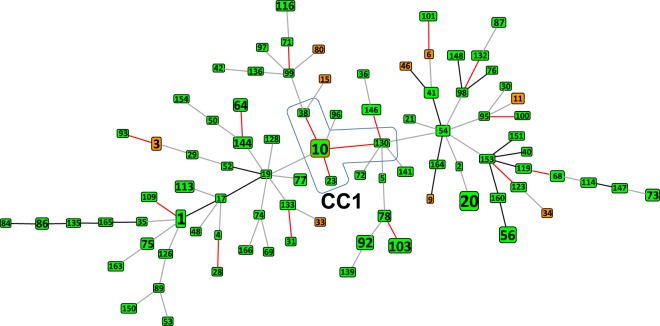

K. variicola MLST allowed us to analyze the allelic profile of the K. variicola isolates included in this study using the goeBURST algorithm. Figure 2 shows the sequence types of major isolates and ST relatedness. A total of 166 STs were identified from among the 254 isolates included in this study, and 127 are unique. The founder ST10 and ST23, ST38 and ST130 with a single locus variants (SLVs) comprise Clonal Complex 1 (CC1). ST10 corresponds to one of the most predominant STs, representing 70% of all strains in CC1 (7/10). Moreover, all CC1 strains have a human origin, and they were obtained from five different countries (China, Denmark, Mexico, Tanzania and the USA). In addition to CC1, other 12 SLVs (42 isolates) were identified by goeBURST analysis and only three SLV were from the same country. Approximately 85% of the SLVs were isolated from humans, 9% from the environment and 5% from plants. None of these SLVs from plants or the environment share a relationship. All STs described above present an SLV relationship, without sharing a clear common origin or country. The same heterogeneity was observed for 17 double locus variants (DLVs) (40 isolates) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

goeBURST analysis of K. variicola isolates. Single-locus variants (SLVs) are in red, double-locus variants (DLVs) are in black, and triple-locus variants (TLVs) are in grey. The founder ST10 and ST38, ST23 and ST130 with an SLV correspond to Clonal Complex 1 (CC1). The isolates from humans and plants are in green and orange squares, respectively. The size of a node is proportional to the number of isolates presenting that ST in the database (Supplementary Dataset).

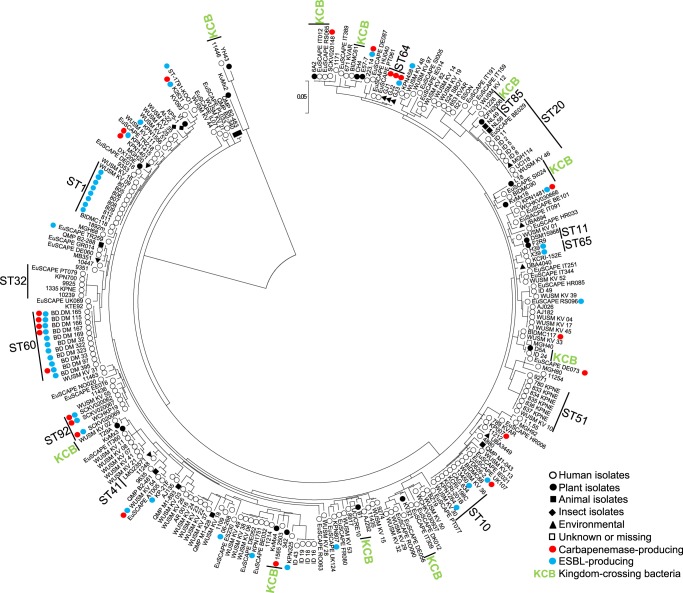

K. variicola isolates obtained from different sources are suggested to be derived from a common genetic pool, without segregation between isolates from these sources13,36. In addition, Potter et al.18 reveal two distant lineages among K. variicola genomes using phylogenetic analysis of the core genome. In this study, the phylogenetic analysis was carried out using the seven concatenated genes from K. variicola MLST (Fig. 3). Similarity to previous works, showed not segregate isolates with regard to origin of the sample and the distant lineage was formed by the same K. variicola KvMx2 and YH43 isolates obtained from sugarcane and potato plants, respectively. In addition, in this distant lineage also grouped the K. variicola 11446 isolate obtained from humans (Fig. 3). The YH43 isolate is another case of misclassification of K. variicola, which was described as K. pneumoniae37.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of K. variicola isolates obtained from different sources. The tree includes the seven concatenated genes from genomes and the isolates described in the present study. Isolates associated with human infection are indicated by white circles, endophyte and rhizosphere isolates with black circles, isolates obtained from animals with black square, insect isolates with black diamond, environmental isolates with black triangles and isolates with unknown or missing origin with white squares. ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing isolates are represented by blue and red circles, respectively. KCB corresponds to kingdom-crossing bacteria identified in the analysis.

The isolates obtained from public data bases were mostly obtained from humans (84.6%), followed by plants (7.0%), animals (3.5%), the environment (3.1%), insects (0.7%) and unknown or missing origin (0.7%). Clusters that corresponds to isolates of the same ST and KCB were revealed by phylogenetic analysis (only the most representatives are indicated in the Fig. 3). Isolates from human and plants phylogenetically related and that may be correspond KCBs are showed; these isolates are as follows: 11226 and CFN2006; L18, EuSCAPE_SI024, BIDMC90 and KvMx18; EuSCAPE_IT309 and KV321; AJ292 and B1; 342, 1565/2503 and KvMx4; WUSM_KV_02 and T29A and YH43 and 11446. Moreover, the At-2231 and KP5-138 isolates obtained from insects, together with the VI isolates from plants1, are phylogenetically related. However, MB351 obtained from the environment (industrial effluent), EuSCAPE_DE060 and EuSCAPE_GR014 from humans and QMP_B2_288 from an animal (bovine) are phylogenetic related. Interestingly, isolates 11248 and LMG23571 obtained from humans and the environment in Mexico and Singapore, respectively, belong to ST41 (Supplementary Dataset and Fig. 1).

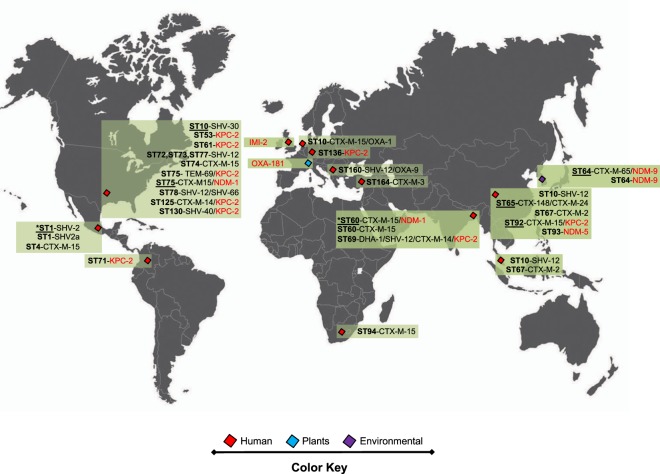

The molecular epidemiology of ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing K. variicola isolates were explored using published data and for unpublished genomes the acquisition of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics due to β-lactamases was determined in silico (Fig. 4) (see Material and Methods). ESBL-producing isolates belong to ST1 (8/9 isolates), ST4, ST10 (2/7 isolates), ST14, ST57 (1/2 isolates), ST60 (6/11), ST64 (1/3 isolates), ST65 (2/2 isolates), ST69, ST72, ST74, ST76, ST77 (1/2 isolates), ST78 (1/2 isolates), ST92 (3/4 isolates), ST94, ST125 (1/2 isolates), ST130, ST160 and ST164. ESBLs SHV-type and CTX-15 were the most prevalent (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Dataset). Several ST described above also are carbapenemase-producing isolates, which have been described in different countries. In the USA, ST53, ST61, ST75, ST125 and ST130 were found to be KPC-2 producers and, in some cases, in combination with ESBL SHV- or CTX-M-type strains. Similarly, ST76 produces NDM-1 and CTX-M-15. Another carbapenemase-producing K. variicola isolates on the American continent are ST71 with KPC-2. In Europe, ST136 with KPC-2 has been reported. In Asian countries, ST60 corresponds to the pediatric outbreak in Bangladesh and is composed of CTX-M-15 and NDM-1 producers and the ST69 in this country produces ESBLs and KPC-2. In South Korea, ST64 obtained from river water was positive for NDM-9 and CTX-M-65 in some isolates. Regarding China, ST92 and ST93 produce KPC-2 and NDM-5, in combination with CTX-M-15 for ST93. Half of the isolates described as carbapenemase-producing also were positive for ESBLs of TEM-, SHV- or CTX-M-type families (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Dataset).

Figure 4.

Molecular epidemiology of ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing K. variicola isolates. Underlined STs contain several isolates. ST and ESBL- and/or carbapenemase-producing genes corresponding to K. variicola outbreaks are marked with asterisks. The origin of the isolates is shown in color codes. The IMI-2 and OXA-181 carbapenemase-producing K. variicola isolates lack WGS data.

Although no WGS data are available in two reports of carbapenemase-producing K. variicola isolates39,40, we would like to highlight these studies because they correspond to the first descriptions of carbapenemase-producing K. variicola isolates. The plasmid-borne carbapenemase genes identified were OXA-181 and IMI-2, from Switzerland and the United Kingdom, respectively.

Currently, accurate differentiation of K. pneumoniae, K. quasipneumoniae, K. variicola and K. quasivariicola is not routinely performed in the clinical setting. The main reason is the lack of implementation of the methods available in clinical or research laboratories41. Therefore, any of the K. quasipneumoniae, K. variicola and K. quasivariicola isolates are continuously misclassified as K. pneumoniae. The clinical importance of K. variicola is overshadowed by inaccurate identification, and thus, the actual prevalence has also been underestimated. Initially, correctly identified K. variicola was achieved by phylogenetic analysis mainly using the rpoB gene. However, several molecular approaches have been proposed to properly detect these species12,23,24, and MALDI-TOF identification of these species has been improved5. In addition, one-step PCR amplification of chromosomal β-lactamases of K. pneumoniae, K. quasipneumoniae and K. variicola for identification should be considered carefully. Long et al.13 identified a rare recombinant of the OKP/LEN core genes. In the present work, the LEN-type gene was found in 98.8% of the K. variicola genomes, whereas the other 1.2% of the genomes lacked for LEN-type chromosomal β-lactamase (Supplementary Dataset), a fact that should be considered when chromosomal β-lactamase genes are used for species identification. Nevertheless, at the genomic level, misclassifications among K. pneumoniae, K. quasipneumoniae and K. variicola have recently been rectified15. An excellent option at the genomic level is ANI, a tool proposed for the correct identification of bacterial species15,42,43. Overall, the increasing number of options for differentiating K. variicola from closely related species in the K. pneumoniae complex increases the number of isolates, and more WGS projects for this bacterial species will likely be conducted in the near future.

Considering the findings described above, the ANI tool was implemented in our MLST scheme for K. variicola (http://mlstkv.insp.mx) for correct identification of bacterial species using WGS data. These WGS data is compared with the reference genomes of K. pneumoniae, K. quasipneumoniae, K. variicola and K. quasivariicola, and once ANI confirme that the genome correspond to K. variicola (>95%), the ST is assigned according to the K. variicola MLST database. If Klebsiella sp. genomes were found to be <95% homologous, then they are not assigned an ST, and the platform determine whether the species correspond to any of the other species included in the ANI analysis. In addition, if MLST for K. variicola is implemented in laboratories interested in determining STs among K. variicola isolates, the isolates negative for pyrG by PCR amplification suggest the possibility that these isolates do might not correspond to K. variicola.

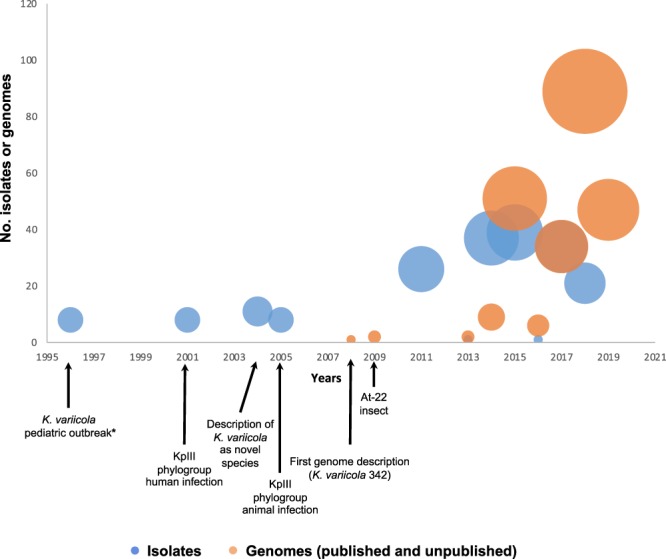

Figure 5 depicts the epidemiological history of K. variicola based on the year of publication. Although the first three works related to K. variicola were published in 2001, 2004 and 2008, the bacteria identified were isolated in the previous years. An outbreak of K. variicola was described in 2007, but the isolates were obtained in 199633. These isolates are related to bloodstream infections from a pediatric outbreak in Mexico. The first K. variicola isolate (801) was obtained on April 09 of 1996 (Fig. 5). Subsequently, this isolate was subjected to WGS and used to develop a PCR-multiplex assay12 and considered as ST1 in this work. To describe K. variicola as a new bacterial species in 20041, a phylogenetic analysis that included K. pneumoniae isolates identified three phylogroups, named KpI, KpII and KpIII, was described in 200144. The KpIII phylogroup was mentioned by Rosenblueth et al. (2004), which corresponds to K. variicola1. In the next year (2005), several isolates belonging to the KpIII group and obtained from veterinary infections (dog, monkey and bird) in the Netherlands also correspond to K. variicola45. The first K. variicola misclassification corresponded to K. pneumoniae 342, and several reports subsequently described this isolate as K. variicola. One year later, K. variicola At-22 was obtained from leaf-cutter ant-fungus gardens in South America31, and numerous K. variicola genomes have since been described (Fig. 5). Several studies have considered the misclassification existing within the Klebsiella genus12,13,15,16 it has allowed that genomes that correspond to K. variicola could be correctly identified and updated. The population structure, virulence and antibiotic resistance of K. variicola has been addressed through WGS34, and the BioProject (PRJEB10018) recently identified K. variicola clinical isolates in several European countries (Fig. 1). In general, rigorous molecular epidemiological studies of K. variicola require an MLST scheme, which allow for surveillance of multidrug-resistant and hypervirulent clones.

Figure 5.

Timeline description of K. variicola isolates and genomes described in public databases. The KpIII group corresponds to K. variicola. The K. variicola pediatric outbreak marked with asterisk corresponds to the isolation date of the clinical isolates.

Comparison of MLST schemes

The K. pneumoniae MLST scheme works for K. variicola and different studies have applied the K. pneumoniae MLST scheme for typing K. variicola isolates13,14,18. However, for an unknown reason, a large number of K. variicola isolates were not assigned an ST, considering that the genomes have been determined13,18. In this study, both MLST schemes were compared using K. variicola genomes.

K. pneumoniae MLST was developed in 2005, when new species closely related to K. pneumoniae were still unknown. Of the seven locus (rpoB, gapA, mdh, pgi, phoE, infB and tonB) of the K. pneumoniae MLST scheme, three (rpoB, pgi and phoE) are shared with the K. variicola MLST scheme. The tonB was not considered for K. variicola MLST because in the case of K. pneumoniae, several nucleotides have been inserted at this locus. However, the K. pneumoniae MLST scheme eliminates inserted nucleotides (https://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/klebsiella/klebsiella.html). Such nucleotide insertion was also identified in the tonB gene of K. variicola. Considering its role in the binding and transport of siderophores, tonB might be undergoing selection pressure. These proteins could be directly involved in pathogenicity46, which has been observed an increase in pathogenicity for Klebsiella spp., with strains of K. pneumoniae, K. quasipneumoniae and K. variicola being hypervirulent35,47–49. Further investigation is needed to this respect.

In the case of rpoB, leuS and fusA and pyrG genes were considered in the K. variicola MLST scheme, because the first three genes were proposed for phylogenetic differentiation of K. pneumoniae, K. variicola and K. quasipneumoniae2. In the case of pyrG, a GTP synthase class-I is absent in K. pneumoniae and as mentioned above, this gene may contribute to the proper identification of K. variicola.

Moreover, 178 of the K. variicola genomes included in this study were subjected to ST assignments in the K. pneumoniae MLST scheme, of them 11.8% of the genomes were not assigned to an ST because they corresponded to new ones. K. variicola genomes with an assigned ST were analyzed through goeBURST analysis using the K. pneumoniae MLST database. This result showed a clear dispersion of K. variicola isolates, considering that the STs assigned to K. variicola isolates are shared ST profile with the K. pneumoniae isolate deposited in the K. pneumoniae MLST database (Fig. S1). However, the goeBURST analysis using the K. variicola MLST database revealed that some of these K. variicola isolates are close related to each other when they were separated by an SLV. These data emphasize that it is difficult to establish genetic relationships among K. variicola isolates using the K. pneumoniae MLST scheme because K. variicola isolates are related to those of K. pneumoniae instead of those of their own species. In summary, using the same MLST scheme for closely related bacterial species is not discriminative.

Finally, the allelic profile of K. variicola genomes was analyzed using both K. pneumoniae and K. variicola MLST schemes (Fig. S2). A heatmap shows higher variability when the K. variicola MLST scheme was applied in the examined K. variicola genomes.

Impact of K. variicola in different environments

In the last year, K. variicola has been strongly suggested to cause serious infections in humans, including hospital outbreaks, which has increased the phenotypic identification of ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing in environmental and clinical isolates. An increase in virulence has also been described, including the identification of hypermucoviscous50 and hypervirulent33 strains and those causing high mortality in a pediatric outbreak51. Additionally, colistin-resistant isolates have been reported, and the chromosomal mechanisms that are responsible for this phenotype have been identified35. Outside the clinical environment, signs of infection in farm and wild animals have been observed and strongly correlated with some insects. K. variicola is widely distributed among different groups of plants, mainly those consumed by humans, which facilitates the transfer of these bacteria from plants to humans. Accordingly, K. variicola species has been proposed to constitute a cross-kingdom bacterium. In the environment, K. variicola has been detected in rivers and on inert surfaces, and a review of K. variicola details the wide range of environments in which K. variicola has been detected as well as its use in industry6. In addition to the nitrogen-fixation capacity of K. variicola, these findings reveal clear differences from other species of the Klebsiella genus, mainly K. pneumoniae8,16,17,29.

Conclusions

K. variicola is a bacterial species that has been misclassified as K. pneumoniae for years, and it has also been misclassified as K. quasipneumoniae. K. variicola and K. pneumoniae share clinical settings and both are endophytes in plants and cause infections in livestock and wild animals. In clinical settings, K. variicola shows clear differences with regard to infection, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis. There are several approaches for the proper identification of K. variicola among K. pneumoniae complex. The database of K. variicola MLST will allow the molecular epidemiology of this bacterial species and establish the identification of possible pandemic clones. In addition, this study reveals a possible route of transmission of this bacterial endophyte from plants to humans. Although this phenomenon was previously identified, several results of the present study strengthen this evidence. K. variicola and K. pneumoniae are closely related bacterial species which must be stored separately, preventing one from masking the other and the relationships among the same bacterial species can being found.

Materials and Methods

K. variicola MLST scheme

For the development of the K. variicola MLST scheme, seven housekeeping genes were selected after AMPHORA (AutoMated PHylogenOmic infeRence) analysis51. The analysis was performed using thirty-three K. variicola proteomes. Primer pairs were successfully designed (using the Primer-BLAST tool https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) for PCR amplification and sequencing of an internal position of the seven genes.

K. variicola genomes

In total, 226 K. variicola genomes were obtained from public GenBank/ENA databases (01/05/2019). These genomes were validated as belonging to K. variicola using the Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) tool45. The reference genomes for each bacterial species included are K. pneumoniae MGH78578 (GenBank Accession number CP000647.1), K. quasipneumoniae 18A069 (GenBank Accession number CBZM000000000), K. variicola At22 (GenBank Accession number CP001891.1) and K. quasivariicola KPN1705 (GenBank Accession number CP022823.1).

Sequence type determination in K. variicola genomes and isolates

K. variicola MLST scheme STs were determined for 226 K. variicola genomes and a collection of 28 K. variicola isolates obtained from plants and humans in Mexico. In these isolates, the PCR amplification products were carried out following the instructions described in this study (Table 1). The nucleotide sequences of the 7 MLST genes were obtained using BigDyeTM Terminator v3.1 and analyzed with the Applied Biosystems 3130 platform. For more details of the PCR conditions visit the page of K. variicola MLST scheme (http://mlstkv.insp.mx).

goeBURST analysis

The goeBURST-1.2.152 program was used to analyze STs of K. variicola isolates and to assign isolates to a clonal complex (CC). A clonal complex is defined as a set of similar STs with six identical locus. A CC is formed by the founder ST and its SLVs.

Phylogenetic analysis

The phylogenetic analysis was performed using the 7-locus K. variicola MLST concatenated genes, and a Maximum Likelihood phylogeny tree was generated using Mega software v7.0.26. The Tamura-Nei model with discrete Gamma distribution was applied to model evolutionary rate differences among sites (4 categories (+G, parameter = 0.1133))53.

Implementation of ANI by proper K. variicola bacterial species

ANI tool45 analysis was implemented in the K. variicola MLST homepage (http://mlstkv.insp.mx) to ensure the correct identification of K. pneumoniae, K. quasipneumoniae, K. variicola and K. quasivariicola. The reference genomes for each bacterial species analyzed using ANI are K. pneumoniae MGH78578 (GenBank Accession number CP000647.1), K. quasipneumoniae 18A069 (GenBank Accession number CBZM000000000), K. variicola At22 (GenBank Accession number CP001891.1) and K. quasivariicola KPN1705 (GenBank Accession number CP022823.1).

Molecular epidemiology of K. variicola

The molecular epidemiology of susceptible, ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing K. variicola was established according to respective publications (Supplementary Dataset). In addition, isolates with genomic data but unpublished β-lactamases were determined using ResFinder based on acquired antimicrobial resistance genes (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/)54.

Comparison of MLST typing schemes

The MLST K. pneumoniae scheme was used to determine STs for 178 K. variicola genomes included in the study. goeBURST analysis was carried out using the allelic profile. A heatmap was drawn to determine the distances between the allelic profiles of the seven genes of the K. pneumoniae and K. variicola MLST schemes and Multiple Experiment Viewer MeV version 4.8.1 software.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant 256988 from SEP-CONACyT (Secretaría de Educación Pública-Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología).

Author Contributions

H.B.C. and A.A.-V. contributed equally to this work. U.G.-R., N.R.-M., H.B.-C., J.D.-B. and A.A.-V. contributed to analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. H.B.-C., M.B.-R., O.M.P.-C. and J.D.-B. performed the experiments. A.A.-V., E.A.-V., J.R. and L.L.-A. developed the software. U.G.-R. contributed reagents/materials.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Humberto Barrios-Camacho and Alejandro Aguilar-Vera contributed equally.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-46998-9.

References

- 1.Rosenblueth M, Martinez L, Silva J, Martinez-Romero E. Klebsiella variicola, a novel species with clinical and plant-associated isolates. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2004;27:27–35. doi: 10.1078/0723-2020-00261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brisse S, Passet V, Grimont PA. Description of Klebsiella quasipneumoniae sp. nov., isolated from human infections, with two subspecies, Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae subsp. nov. and Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae subsp. nov., and demonstration that Klebsiella singaporensis is a junior heterotypic synonym of Klebsiella variicola. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014;64:3146–3152. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.062737-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Long, S. W. et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing of a Human Clinical Isolate of the Novel Species Klebsiella quasivariicola sp. nov. Genome Announc. 5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Rodrigues, C. et al. Description of Klebsiella africanensis sp. nov., Klebsiella variicola subsp. tropicalensis subsp. nov. and Klebsiella variicola subsp. variicola subsp. nov. Res. Microbiol (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Rodrigues C, Passet V, Rakotondrasoa A, Brisse S. Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella quasipneumoniae, Klebsiella variicola and Related Phylogroups by MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2018;9:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duran-Bedolla, J., Garza-Ramos, U., Rodriguez-Medina, N., Aguilar-Vera A. & Barrios-Camacho, H. Klebsiella variicola: a pathogen and eco-friendly bacteria with applications in biolgical and industrial processes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. under review (2019).

- 7.Rodriguez-Medina, N., Barrios-Camacho, H., Duran-Bedolla, J. & Garza-Ramos, U. Klebsiella variicola: an emerging pathogen in humans. Emerging Microbes and Infectious. 8, 973-988 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Lin L, et al. Complete genome sequence of endophytic nitrogen-fixing Klebsiella variicola strain DX120E. Stand. Genomic. Sci. 2015;10:22. doi: 10.1186/s40793-015-0004-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afzal AM, Rasool MH, Waseem M, Aslam B. Assessment of heavy metal tolerance and biosorptive potential of Klebsiella variicola isolated from industrial effluents. AMB. Express. 2017;7:184. doi: 10.1186/s13568-017-0482-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di DY, Jang J, Unno T, Hur HG. Emergence of Klebsiella variicola positive for NDM-9, a variant of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase, in an urban river in South Korea. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017;72:1063–1067. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gomi, R. et al. Characteristics of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Wastewater Revealed by Genomic Analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 62 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Garza-Ramos U, et al. Development of a multiplex-PCR probe system for the proper identification of Klebsiella variicola. BMC. Microbiol. 2015;15:64. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0396-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Long, S. W. et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing of Human Clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates Reveals Misidentification and Misunderstandings of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella variicola, and Klebsiella quasipneumoniae. mSphere. 2 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Maatallah M, et al. Klebsiella variicola is a frequent cause of bloodstream infection in the stockholm area, and associated with higher mortality compared to K. pneumoniae. PLoS. One. 2014;9:e113539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Romero E, et al. Genome misclassification of Klebsiella variicola and Klebsiella quasipneumoniae isolated from plants, animals and humans. Salud Publica Mex. 2018;60:56–62. doi: 10.21149/8149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen M, et al. Genomic identification of nitrogen-fixing Klebsiella variicola, K. pneumoniae and K. quasipneumoniae. J. Basic Microbiol. 2016;56:78–84. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201500415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt KE, et al. Genomic analysis of diversity, population structure, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae, an urgent threat to public health. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E3574–E3581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501049112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Potter, R. F. et al. Population Structure, Antibiotic Resistance, and Uropathogenicity of Klebsiella variicola. MBio. 9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Martinez J, Martinez L, Rosenblueth M, Silva J, Martinez-Romero E. How are gene sequence analyses modifying bacterial taxonomy? The case of Klebsiella. Int. Microbiol. 2004;7:261–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seki M, et al. Fatal sepsis caused by an unusual Klebsiella species that was misidentified by an automated identification system. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013;62:801–803. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.051334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chun-Yan W, et al. Endophytic nitrogen-fixing Klebsiella variicola strain DX120E promotes sugarcane growth. Biology and Fertility of Soils. 2014;50:657–666. doi: 10.1007/s00374-013-0878-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alves MS, Dias RC, de Castro AC, Riley LW, Moreira BM. Identification of clinical isolates of indole-positive and indole-negative Klebsiella spp. J Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:3640–3646. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00940-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berry GJ, Loeffelholz MJ, Williams-Bouyer N. An Investigation into Laboratory Misidentification of a Bloodstream Klebsiella variicola Infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:2793–2794. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00841-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fonseca EL, et al. A one-step multiplex PCR to identify Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella variicola, and Klebsiella quasipneumoniae in the clinical routine. Diagn. Microbiol Infect. Dis. 2017;87:315–317. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yasuhara-Bell, J., Ayin, C., Hatada, A., Yoo, Y. & Schlub, R. L. Specific detection of Klebsiella variicola and K. oxytoca by Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification. J Plant Pathol Microbiol6 (2015).

- 26.van Veen SQ, Claas EC, Kuijper EJ. High-throughput identification of bacteria and yeast by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry in conventional medical microbiology laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:900–907. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02071-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diancourt L, Passet V, Verhoef J, Grimont PA, Brisse S. Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:4178–4182. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4178-4182.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao X, Xu C, Domagala J, Drlica K. DNA topoisomerase targets of the fluoroquinolones: a strategy for avoiding bacterial resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:13991–13996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez-Romero E, Rodriguez-Medina N, Beltran-Rojel M, Toribio-Jimenez J, Garza-Ramos U. Klebsiella variicola and Klebsiella quasipneumoniae with capacity to adapt to clinical and plant settings. Salud Publica Mex. 2018;60:29–40. doi: 10.21149/8156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinto-Tomas AA, et al. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the fungus gardens of leaf-cutter ants. Science. 2009;326:1120–1123. doi: 10.1126/science.1173036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noinaj N, Guillier M, Barnard TJ, Buchanan SK. TonB-dependent transporters: regulation, structure, and function. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;64:43–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garza-Ramos U, Martinez-Romero E, Silva-Sanchez J. SHV-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) are encoded in related plasmids from enterobacteria clinical isolates from Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 2007;49:415–421. doi: 10.1590/S0036-36342007000600008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y, Feng Y, McNally A, Zong Z. Occurrence of colistin-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella variicola. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:3001–3004. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu W, et al. Whole genome analysis of halotolerant and alkalotolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Klebsiella sp. D5A. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26710. doi: 10.1038/srep26710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo Y, et al. Complete Genomic Analysis of a Kingdom-Crossing Klebsiella variicola Isolate. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2428. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fouts DE, et al. Complete genome sequence of the N2-fixing broad host range endophyte Klebsiella pneumoniae 342 and virulence predictions verified in mice. PLoS. Genet. 2008;4:e1000141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Iwase, T., Ogura, Y., Hayashi, T. & Mizunoe, Y. Complete Genome Sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae YH43. Genome Announc. 4 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38. Medrano, E. G., Forray, M. M. & Bell, A. A. Complete Genome Sequence of a Klebsiella pneumoniae Strain Isolated from a Known Cotton Insect Boll Vector. Genome Announc. 2 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Zurfluh K, Poirel L, Nordmann P, Klumpp J, Stephan R. First detection of Klebsiella variicola producing OXA-181 carbapenemase in fresh vegetable imported from Asia to Switzerland. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2015;4:38. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0080-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hopkins KL, et al. IMI-2 carbapenemase in a clinical Klebsiella variicola isolated in the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017;72:2129–2131. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fontana, L., Bonura, E., Lyski, Z. & Messer, W. The Brief Case: Klebsiella variicola-Identifying the Misidentified. J. Clin. Microbiol. 57 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42. Figueras, M. J., Beaz-Hidalgo, R., Hossain, M. J. & Liles, M. R. Taxonomic affiliation of new genomes should be verified using average nucleotide identity and multilocus phylogenetic analysis. Genome Announc. 2 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Goris J, et al. DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007;57:81–91. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brisse S, Verhoef J. Phylogenetic diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca clinical isolates revealed by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA, gyrA and parC genes sequencing and automated ribotyping. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001;51:915–924. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-3-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brisse S, Duijkeren E. Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility of 100 Klebsiella animal clinical isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 2005;105:307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Russo, T. A. et al. Identification of Biomarkers for Differentiation of Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae from Classical K. pneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 56 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Breurec S, et al. Liver Abscess Caused by Infection with Community-Acquired Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016;22:529–531. doi: 10.3201/eid2203.151466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farzana, R. et al. Outbreak of Hypervirulent Multi-Drug Resistant Klebsiella variicola causing high mortality in neonates in Bangladesh. Clin. Infect. Dis. (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Shon AS, Bajwa RP, Russo TA. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae: a new and dangerous breed. Virulence. 2013;4:107–118. doi: 10.4161/viru.22718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Garza-Ramos, U. et al. Draft Genome Sequence of the First Hypermucoviscous Klebsiella variicola Clinical Isolate. Genome Announc. 3, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Wu M, Eisen JA. A simple, fast, and accurate method of phylogenomic inference. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R151. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-10-r151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feil EJ, Li BC, Aanensen DM, Hanage WP, Spratt BG. eBURST: inferring patterns of evolutionary descent among clusters of related bacterial genotypes from multilocus sequence typing data. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:1518–1530. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.5.1518-1530.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zankari E, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.