Abstract

The combined regulation of a network of inhibitory and activating T cell receptors may be a critical step in the development of chronic HCV infection. Ex vivo HCV MHC class I + II tetramer staining and bead-enrichment was performed with baseline and longitudinal PBMC samples of a cohort of patients with acute, chronic and spontaneously resolved HCV infection to assess the expression pattern of the co-inhibitory molecule TIGIT together with PD-1, BTLA, Tim-3, as well as OX40 and CD226 (DNAM-1) of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells, and in a subset of patients of HCV-specific CD8+ T cells. As the main result, we found a higher expression level of TIGIT+ PD-1+ on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells during acute and chronic HCV infection compared to patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection (p < 0,0001). Conversely, expression of the complementary co-stimulatory receptor of TIGIT, CD226 (DNAM-1) was significantly decreased on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells during chronic infection. The predominant phenotype of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells during acute and chronic infection was TIGIT+, PD-1+, BTLA+, Tim-3−. This comprehensive phenotypic study confirms TIGIT together with PD-1 as a discriminatory marker of dysfunctional HCV-specific CD4+ T cells.

Subject terms: Hepatitis C virus, Immunological memory, Hepatitis C

Introduction

In the majority of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infected patients, the virus persists and the patients progress to chronic infection, although a minority of individuals is able to spontaneously control viral replication1–5. In addition to the influence of genetic factors like the IL-28 polymorphism that strongly determines the course of natural infection, it is thought that HCV-specific CD4+ T cell dysfunction followed by CD8+ T cell exhaustion and viral escape is the main reason for this loss of viral control1,6–8. Co-inhibitory receptors are critical regulators of T cell exhaustion in the context of acute and chronic viral infections. We and others could previously show that PD-1 is a central regulator of T cells in HCV infection9,10. Further studies show that exhausted CD8+ T cells in chronic HCV express multiple co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory receptors that converge to keep chronically activated effector CD8+ T cells in check9–14. However, less is known about the expression of different co-inhibitory receptors on virus-specific CD4+ T cells mainly due to technical reasons since virus-specific CD4+ T cells have a lower frequency than virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood1,15. A recent human study of the co-inhibitory receptor distribution for peptide-stimulated HIV-specific CD8+ as well as CD4+ T cells showed a varying phenotypic and functional pattern according to the disease status of the HIV infection and subset analysed16.

In tumour and chronic infection mouse models, the essential role of TIGIT (T cell immunoglobulin and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif [ITIM] domain) as a regulator of the anti-tumour and anti-viral CD8+ T cell response has been demonstrated17–20.

Recently, is has been shown that increased frequencies of TIGIT+ and TIGIT+ PD-1+ CD8+ T cells correlated with parameters of HIV disease progression21. Ex vivo combinational antibody blockade of TIGIT and PD-L1 enhanced anti-tumour immunity18,22, restored viral-specific CD8+ T cells, and reinvigorated the CD4+ T cell response17,21.

To assess the pattern of immune-modulatory receptor expression of virus-specific CD4+ T cells in viral hepatitis in more detail11,23–30, we analysed the co-inhibitory receptor TIGIT together with an array of different co-inhibitory molecules like PD-1, BTLA, Tim-3 as well as OX40 and CD226 (DNAM-1) on ex vivo bulk and MHC class II tetramer+ HCV-specific T cells24,31–40. In parallel, we stained a subset of patients with HCV-specific MHC class I tetramers to compare co-inhibitory molecule expression pattern of HCV-specific CD4+ versus HCV-specific CD8+ T cells.

Here, we present a comprehensive analysis of the expression pattern of TIGIT of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells as part of a network of co-inhibitory and co-stimulatory receptors that are known to induce T cell dysfunction and which is possibly associated with loss of viral control in the majority of acutely HCV infected patients.

Results

Increased expression level of TIGIT on bulk CD4+ T cells of patients with acute and chronic HCV infection

Recently, a critical role for TIGIT in regulating virus-specific CD4+ T cell responses in chronic HIV infection41 has been described, but little is known about the role of TIGIT together with PD-1 and TIGIT’s complementary receptor CD226 on T cells of HCV patients. The aim of this study was to comprehensively analyze the expression pattern of TIGIT together with additional co-inhibitory molecules on bulk and HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of HCV patients with different disease status.

First, we assessed the ex vivo surface expression of TIGIT on total CD4+ T cells of patients with acute (n = 10), chronic (n = 11), spontaneously resolved (n = 8) HCV infection and healthy controls (n = 10) (Table 1, Suppl. 1A–C). We observed a significantly higher frequency of bulk TIGIT+ CD4+ T cells of patients with HCV infection compared to healthy controls. Bulk CD4+ T cells of acutely infected HCV patients tended to have the highest frequencies followed by chronically infected HCV patients and patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection (Suppl. 1B). Based on the differentiation markers CD45RO and CCR7, we defined naïve and memory subsets (CCR7−/CD45RO–terminal effector-TEMRA; CCR7+/CD45RO–naïve T cells-Tnaïve; CCR7−/CD45RO+–effector memory–TEM; CCR7+/CD45RO+–central memory–TCM) of bulk CD4+ T cells and assessed the TIGIT expression of each memory subset. We could detect a significant higher TIGIT expression on all CD4+ T cell memory subsets of acutely HCV infected patients while the general level of TIGIT was highest across all patient groups in the effector memory compartment and lowest in the naïve T cell compartment (Suppl. 1C).

Table 1.

Clinical, virological, and immunological patient characteristics.

| Infection status | Age/Sex | HLA-class II | Genotype | Peak VL (IU/ml) | VL (IU/ml)* | Peak ALT (U/l) | ALT (U/l)* |

Longitudinal samples | Outcome | Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aHCV 1 | 68/f | DRB1*01:01, *14:01 | 1a | / | 4000000 | / | 51 | yes | cHCV/SVR | peg-IFN/RBV (24 W) |

| aHCV 2 | 42/m | DRB1*14:01, *15:01 | 1a | 70000 | 70000 | 558 | 558 | no | cHCV | / |

| aHCV 3 | 51/f | DRB1*03:01, *15:01 | 2b | 8000 | 8000 | 1548 | 798 | no | Sp. R | / |

| aHCV 4 | 54/f | DRB1*01:02,*03:01 | 3a | 4000000 | 30000000 | 1273 | 1084 | yes | Sp. R | / |

| aHCV 5 | 47/f | DRB1*01:02, *15:01 | n.a. | Llod | Llod | 63 | 63 | yes | Sp. R | / |

| aHCV 6 | 22/f | DRB1*01:01, *03:01 | 1a | 400000 | 30000 | 368 | 40 | yes | cHCV/SVR | peg-IFN/RBV (24 W) |

| aHCV 7 | 32/m | DRB1*13:02,*15:01 | n.a. | 70000 | 70000 | 1317 | 91 | no | Sp. R | / |

| aHCV 8 | 44/m | DRB1*01:01, *03:01 | 1a | 30000000 | 90000 | 4316 | 1762 | yes | cHCV/SVR | peg-IFN/RBV (24 W) |

| aHCV 9 | 38/f | DRB1*03:01, 15:06 | 3 | 2070000 | 30500 | 521 | 115 | no | cHCV | |

| aHCV 10 | 39/m | DRB1*04:01, *15:01 | 1a | 18040000 | 140 | 2387 | 51 | yes | cHCV/SVR | peg-IFN/RBV (24 W) |

| rHCV 11 | 38/m | DRB1*11:01, *13:02 | n.a. | Llod | Llod | 32 | 22 | no | / | / |

| rHCV 12 | 36/m | DRB1*01:01, *11:01 | n.a. | Llod | Llod | 23 | 23 | no | / | / |

| rHCV 13 | 36/m | DRB1*07:01,*15:01 | n.a. | Llod | Llod | 66 | 43 | no | / | / |

| rHCV 14 | 48/f | DRB1*01:01,*- | n.a. | Llod | Llod | 15 | 10 | no | / | / |

| rHCV15 | 51/f | DRB1*01:01,*14:01 | n.a. | Llod | Llod | 94 | 48 | no | / | / |

| rHCV 16 | 26/m | DRB1*11:02, *12:01 | n.a. | Llod | Llod | 90 | 86 | no | / | / |

| rHCV 17 | 44/m | DRB1*01:01, *27:05 | n.a. | Llod | Llod | 84 | 20 | no | / | / |

| rHCV 18 | 68/m | DRB1*08:03, *11:01 | n.a. | Llod | Llod | 32 | 30 | no | / | / |

| cHCV 19 | 65/m | DRB1*11:01,*15:01 | 1a | 1000000 | 800000 | 100 | 100 | no | / | / |

| cHCV 20 | 60/f | DRB1*04:01, *15:01 | 1b | 9000000 | 9000000 | 68 | 54 | no | / | / |

| cHCV 21 | 28/f | DRB1*13:01, *15:01 | 1b | 2000000 | 2000000 | 43 | 43 | yes | SVR | Ledipasvir/Sofusbuvir (12 W) |

| cHCV 22 | 56/m | DRB1*11:02, *15:01 | 1a | 30000 | 10000 | 374 | 75 | no | / | / |

| cHCV 23 | 63/f | DRB1*07:01, *15:01 | 1b | 10000000 | 2000000 | 138 | 54 | yes | SVR | Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir (12 W) |

| cHCV 24 | 43/m | DRB1*04:04,*15:01 | 1b | 6000000 | 5230000 | 208 | 128 | yes | SVR | Ombitasvir/Paritaprevir/Ritonavir+Dasabuvir (12 W) |

| cHCV 25 | 43/f | DRB1*13:01, *15:03 | 1a | 8741517 | 2884373 | 43 | 43 | no | / | / |

| cHCV 26 | 55/m | DRB1*15:01, *13:01 | 3a | 2775 | 2775 | 91 | 65 | no | / | / |

| cHCV 27 | 40/f | DRB1*03:01,*15:01 | 3 | 4330000 | 4330000 | 42 | 30 | no | / | / |

| cHCV 28 | 39/f | DRB1*04:08, *15:02 | 3 | 24300000 | 24300000 | 71 | 50 | no | / | / |

| cHCV 29 | 46/m | DRB1*07:01, *15:01 | 3 | 15900000 | 13300000 | 208 | 127 | yes | SVR | Sofusbuvir/Velpatasvir (12 W) |

| tHCV 30 | 62/m | DRB1*01:01 | n.a. | Llod | Llod | 58 | 58 | no | SVR | peg-IFN/RBV (24 W) |

| tHCV 31 | 37/m | DRB1*01:01, *07:01 | 3 | 25100000 | 26 | 319 | 43 | no | SVR | Sofusbuvir/Velpatasvir (12 W) |

| tHCV 32 | 37/m | DRB1*15:01, - | 3 | 17800000 | Llod | 25 | 25 | no | SVR | Sofusbuvir/Velpatasvir (12 W) |

| tHCV 33 | 52/m | DRB1*01:01, *11:01 | 1a | 2000000 | Llod | 272 | 107 | no | SVR | peg-IFN/RBV (48 W) |

| tHCV 34 | 39/m | DRB1*07:01, *11:01 | 3 | 850000 | Llod | 157 | 25 | no | SVR | Sofusbuvir/Velpatasvir (12 W) |

TIGIT, PD-1, BTLA and Tim-3 expression pattern of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of acutely and chronically infected patients

In order to analyze TIGIT expression of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells, we stained PBMC ex vivo with a multicolour FACS panel of patients with acute (n = 10), chronic (n = 11) and spontaneously resolved (n = 8) HCV infection using HLA-DRB1*01:01, DRB1*04:01, DRB1*11:01 and DRB1*15:01-restricted tetramers (Table 2) after bead enrichment as previously described42. In accordance with previous reports, the ex vivo frequency of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells was highest in patients with acute HCV infection (ranging from 0,005%-0,15%; median 0,05%) followed by patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection (ranging from 0,0003%-0,1%; median 0,005%) and extremely low in patients with chronic HCV infection (ranging from 0%-0,005%; median 0,0005%) (Suppl. 2A,B).

Table 2.

HLA multimeric complex information.

| HLA-A molecule | HCV Protein | Position | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class II | |||

| DRB1*01:01 | NS4B | aa 1806–1818 | TLLFNILGGWVAA |

| DRB1*04:01 | NS3 | aa 1248–1262 | GYKVLVLNPSVAATL |

| DRB1*04:01 | NS4 | aa 1770–1790 | SGIQYLAGLSTLPGNPAIASL |

| DRB1*15:01 | NS3 | aa 1411–1425 | GINAVAYYRGLDVSV |

| DRB1*15:01 | NS3 | aa 1582–1597 | NFPYLVAYQATVCARA |

| DRB1*11:01 | NS4 | aa 1773–1790 | QYLAGLSTLPGNPAIASL |

| Class I | |||

| A*02:01 | NS3 | aa 1073–1081 | CINGVCWTV |

| A*02:01 | NS3 | aa 1406–1415 | KLVALGINAV |

| A*24:02 | E2 | aa 717–725 | EYVLLLFLL |

Information on the MHC class II and I tetramer specificities employed in this study.

Differentiation markers CD45RO and CCR7 were used to define naïve and memory subset (CCR7−/CD45RO–terminal effector-TEMRA; CCR7+/CD45RO–naïve T cells-Tnaïve; CCR7−/CD45RO+–effector memory–TEM; CCR7+/CD45RO+–central memory-TCM) of HCV–specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells. The vast majority of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells showed a TEM phenotype independent of the infection stage (Suppl. 3A,B), and there was only a minimal decrease of TEM cells of HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of chronically infected HCV patients compared to spontaneously resolved HCV patients.

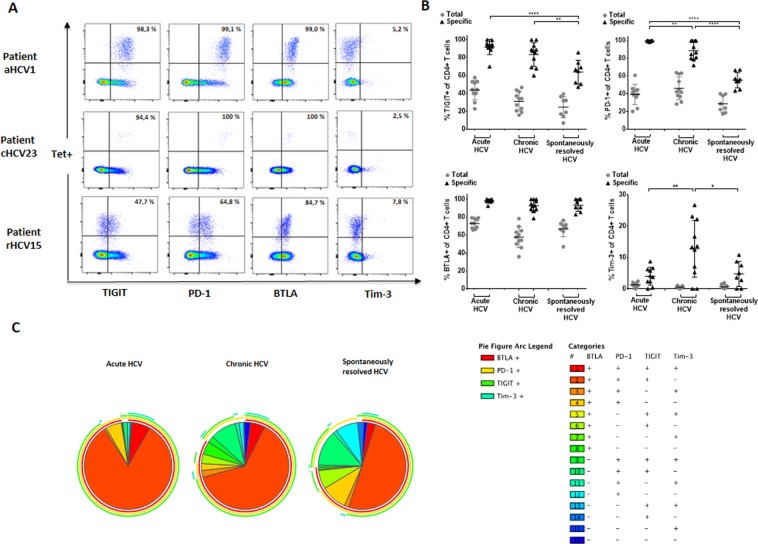

Next, we looked at the expression pattern of TIGIT in combination with a number of additional co-inhibitory markers of HCV–specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of HCV patients with different disease status (Fig. 1A–C). Figure 1A depicts exemplary plots of the inhibitory expression level of TIGIT, PD-1, BTLA, and Tim-3 of MHC class II tetramer+ HCV–specific CD4+ T cells of a patient with a) acute (upper panel), b) chronic (middle panel) and c) spontaneously resolved (lower panel) HCV infection. An increased inhibitory receptor expression level of TIGIT, PD-1, and BTLA, but not Tim-3 was detectable on HCV–specific CD4+ T cells of patients with acute infection and chronic HCV infection. TIGIT and PD-1 expression levels showed marked differences on MHC class II tetramer+ HCV-specific CD4+ T cells between the acute and chronic phase (high expression) and spontaneous resolution (lower expression). BTLA expression levels were generally high in all three patient groups while the Tim-3 expression level of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells was generally much lower – yet highest in chronic HCV patients compared to MHC class II tetramer+ HCV-specific T cells of acutely infected HCV patients or spontaneous resolvers (Fig. 1B). In addition to the differences of the expression frequencies of the different inhibitory molecules at different HCV disease stages, we also observed an significantly increased TIGIT and PD-1 MFI on HCV specific CD4+ T cells from patients with acute (TIGIT; acute vs. resolved: p < 0,0001) (PD-1; acute vs. resolved: p < 0,0001) and chronic (TIGIT; chronic vs. resolved: p < 0,0001) (PD-1; chronic vs. resolved: p < 0,0001) HCV infection compared to patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection (Suppl. 4A,B). In contrast, while we could not detect any difference in the frequency of BTLA on HCV specific CD4+ T cells between the HCV patients with different disease status, the BTLA MFI was significantly higher on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells from patient with acute HCV infection compared to chronic (acute vs. chronic: p < 0,0009) and spontaneously resolved (acute vs. resolved: p < 0,0001) HCV infection (Suppl. 4C).

Figure 1.

(A–C) Higher ex vivo expression of TIGIT and different co-inhibitory molecules on virus-specific CD4+ T cells of acutely and chronically infected HCV patients compared to patients with spontaneously resolved HCV. (A) Representative dot plots depicting the ex vivo co-inhibitory receptor expression (TIGIT, PD-1, BTLA, TIM-3) of HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of patients with acute, chronic and resolved HCV infection. (B) Frequencies of the inhibitory receptors TIGIT, PD-1, BTLA, and Tim-3 on total and HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of patients with acute, chronic, and spontaneously resolved HCV infection. P-values were calculated by the Tukey’s multiple comparison test. P-values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant, where *,** and *** indicate p-values between 0.01 to 0.05, 0.001 to 0.01 and 0.0001 to 0.001 respectively. (C) SPICE analysis of TIGIT, PD-1, BTLA, and Tim-3 co-expression pattern of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of patients with acute (n = 10), chronic (n = 10), and spontaneously resolved (n = 8) HCV infection.

In order to define the detailed expression signature of different co-inhibitory molecules on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells, SPICE analysis43 on HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of patients with different HCV disease status was performed analysing TIGIT, PD-1, BTLA, and Tim-3 co-expression. This analysis revealed that acutely and chronically HCV infected patients generally showed higher frequencies of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells that expressed three inhibitory receptors (TIGIT+ PD-1, BTLA+, Tim-3−) compared to HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of spontaneously resolved HCV patients (Fig. 1C).

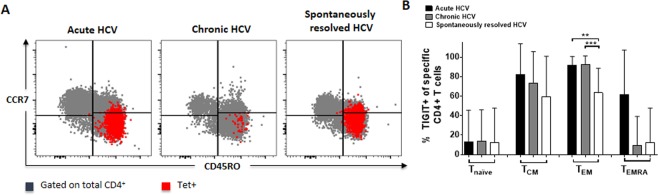

Furthermore, the pattern of TIGIT expression of the different memory subpopulations of MHC class II tetramer+ HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of HCV patients during different stages of disease (Fig. 2A,B) was compared. Recently, it could be shown that TIGIT is mainly expressed on intermediate/transitional and effector T cells of virus-specific CD8+ T cells of patients with HIV21. In contrast, here we could detect that TIGIT was significantly higher expressed within the TEM subset of patients with acute and chronic HCV infection compared to patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection (acute vs. resolved: p = 0,0015) (chronic vs. resolved: p = 0,0009) (Fig. 2B). In the TCM and TEMRA subpopulation, TIGIT expression was relatively stable with no statistically significant difference between patients with acute, chronic or spontaneously resolved HCV infection (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

(A,B) Memory subset distribution of TIGIT+, HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of HCV patients with acute, chronic and spontaneously resolved infection. The differentiation markers CD45RO and CCR7 were used to analyse the ex vivo expression of TIGIT+ HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells within different memory T cell subsets. (A) Representative large dot plots depicting the memory subset distribution of TIGIT+ HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells (red) on an overlay of gated total CD4+ cells (grey) of patients with acute, chronic and spontaneously resolved HCV infection; memory subset definition: CCR7−/CD45RO–terminal effector T cells-TEMRA; CCR7+/CD45RO–naïve T cells-Tnaïve; CCR7−/CD45RO+–effector memory–TEM; CCR7+/CD45RO+–central memory–TCM. (B) Comparison of the TIGIT receptor expression of HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells and different memory T cell subsets in patients with acute (n = 10), chronic (n = 11), and spontaneously resolved (n = 8) infection. P values were calculated by the Tukey’s multiple comparison test. P-values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant, where *,** and *** indicate p-values between 0.01 to 0.05, 0.001 to 0.01 and 0.0001 to 0.001 respectively.

High co-expression of TIGIT and PD-1 on HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of patients during acute and chronic HCV infection

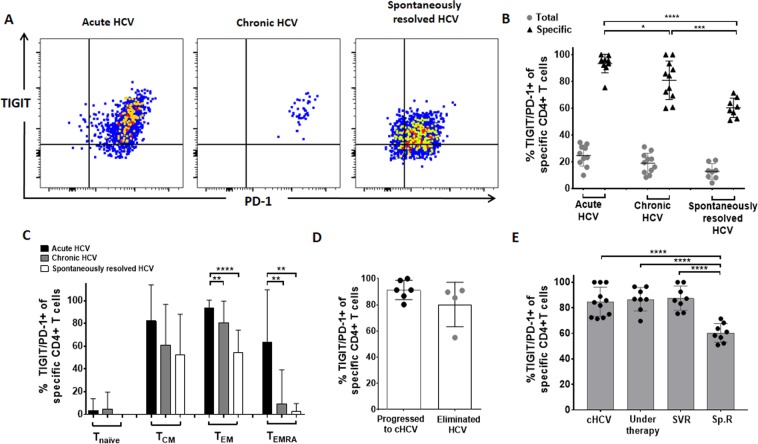

Previous studies have described that especially dual blockade of TIGIT and PD-1 restored anti-viral and anti-tumour T cell effector function in the mouse model17, and this led also to an invigoration of the CD8+ T cell function in HIV patients21. Therefore, we also specifically evaluated TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression of total and HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of patients with acute, chronic and spontaneously resolved HCV infection (Fig. 3A–C). TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression was significantly increased on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of acutely and chronically HCV infected patients compared to the expression of patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection (acute vs. resolved: p < 0,0001) (chronic vs. resolved: p < 0,0001) (Fig. 3B). We further compared the TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression of HCV-specific CD4+ T cell subsets (Fig. 3C). TEM CD4+ T cells of patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection showed a significantly lower TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression than MHC class II tetramer+ HCV-specific TEM CD4+ T cells of patients with acute (acute vs. resolved: p < 0,0001) or than TEM CD4+ T cells of patients with chronic infection (chronic vs. resolved: p = 0,0044).

Figure 3.

(A–E) Ex vivo TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression of HCV–specific CD4+ T cells of patients with acute, chronic and spontaneously resolved HCV infection. (A) Representative large dot plots depicting the ex vivo inhibitory molecule co-expression of TIGIT/PD-1 of HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of patients with acute, chronic and spontaneously resolved HCV infection. (B) TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression on total and HCV-specific CD4+ T cells (C) TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells sub-stratified for different memory T cell subsets of patients with acute (n = 10), chronic (n = 11) and spontaneously resolved (n = 8) HCV infection. (D) Comparison of TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells during acute infection and between patients who later on progressed to chronic versus patients who spontaneously resolved the HCV infection (E) Comparison of the TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of patients with chronic HCV (cHCV–without therapy); chronic HCV patients during HCV treatment (Under therapy; 3 patients received a peg-interferon-based and 5 patients a DAA-based therapy); HCV treated chronic patients with sustained virologic response (SVR; 4 patients received a peg-interferon-based and 4 patients a DAA-based therapy); and patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection (Sp.R). P values were calculated by the Tukey’s multiple comparison test. P-values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant, where *,** and *** indicate p-values between 0.01 to 0.05, 0.001 to 0.01 and 0.0001 to 0.001 respectively.

Next, we investigated whether there was any difference of the TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression of HCV–specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells during acute HCV infection between patients who progressed to chronic versus patients who spontaneously resolved the infection. During the acute HCV infection we found a slight trend of a reduction of the TIGIT/PD-1 frequency of HCV–specific CD4+ T cells of the patient group that developed a chronic HCV (n = 6) infection compared to patients who later spontaneously eliminated the virus (n = 4) (Fig. 3D), however this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0,0933) probably due to the small cohort size and larger cohorts are needed to investigate this question.

We next wanted to explore, whether there is any difference of the TIGIT/PD-1 expression level of HCV–specific CD4+ T cells during and after successful HCV therapy in patients with a sustained virologic response (SVR). Therefore, we compared the TIGIT/PD-1 frequency on MHC class II tetramer+ HCV–specific CD4+ T cells of a subset of chronic HCV patients who underwent HCV therapy. PBMC samples were taken before (cHCV), during and after successful therapy with sustained virologic response (SVR24) (Fig. 3E). Interestingly, we could not detect any difference in TIGIT/PD-1 frequency between a) chronically infected, b) during treatment (cHCV vs. under therapy: p = 0,9692) or c) patients with SVR24 (cHCV vs. SVR: p = 0,9223). This pattern was not different in DAA (direct-acting agents) or PEG-interferon treated patients (data not shown). In contrast, the TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression was significantly lower on HCV–specific CD4+ T cells of patients with spontaneously resolved HCV (under therapy vs. Sp.R: p = <0,0001, SVR vs. Sp.R: p = <0,0001).

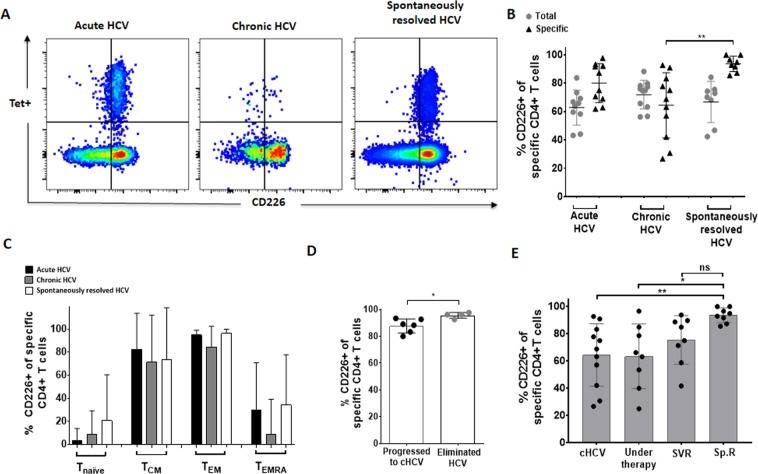

Decreased expression of the co-stimulatory molecule CD226 on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of chronically infected HCV patients compared to patients with spontaneously resolved HCV

In a next step we took a closer look at the expression level of the complementary stimulatory receptor of TIGIT: DNAX accessory molecule 1 (DNAM-1; also called CD226) expression of HCV–specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells at different stages of HCV infection (Fig. 4A–E). Previously it has been suggested that upregulation of TIGIT can potentially inhibit other co-stimulatory molecules like CD22617,44. Generally, CD226 was expressed on the majority of HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4A). However, there were certain differences according to the T cell and HCV disease status (Fig. 4B) and memory T cell subset (Fig. 4C): CD226 expression was significantly lower on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of patients with chronic HCV infection compared to patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection (chronic vs. resolved: p = 0,0010). In our cohort, there were 6 patients with acute HCV infection who went on to become chronically infected and 4 patients who spontaneously resolved the acute HCV infection. Of note, the initial CD226 expression was slightly, but significantly lower in patients who had a chronically evolving disease course (Fig. 4D). Of particular interest, we also analysed CD226 expression of HCV-specific T cells before, during and after successful antiviral therapy. There was an increase of the CD226 expression of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells after HCV therapy initiation and patients with SVR showed comparably high levels to patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection (Fig. 4E). This pattern did not differ between in DAA versus PEG-interferon treated patients (data not shown).

Figure 4.

(A–E) Lower ex vivo expression of the co-stimulatory molecule CD226 on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of chronically infected HCV patients compared to patients with SVR. (A) Representative large dot plots depicting the ex vivo co-expression of TIGIT/PD-1 of HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of patients with acute, chronic and spontaneously resolved HCV infection. (B) CD226 expression of bulk and HCV-specific CD4+ T cells and (C) and in different memory subsets of patients with acute (n = 10), chronic (n = 11) and spontaneously resolved (n = 8) HCV infection. (D) Comparison of the CD226 expression of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells during the acute HCV phase between patients who later progressed to chronic infection versus patients who spontaneously resolved the HCV infection (E) Comparison of the CD226 expression HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of patients with chronic HCV (cHCV–without therapy); chronic HCV patients during HCV treatment (Under therapy; 3 patients received a peg-interferon-based and 5 patients a DAA-based therapy); HCV treated chronic patients with sustained virologic response (SVR; 4 patients received a peg-interferon-based and 4 patients a DAA-based therapy); and patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection (Sp.R). P values were calculated by tukey’s multiple comparison test. P-values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant, where *,** and *** indicate p-values between 0.01 to 0.05, 0.001 to 0.01 and 0.0001 to 0.001 respectively.

TIGIT MFI on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells decreased after HCV-therapy initiation in chronic HCV infection

One major finding of the current study is that the frequency of TIGIT alone or together with PD-1 on HCV–specific CD4+ T cells of patients with chronic HCV infected who were treated remains high, -even after successful therapy and resulting SVR. Nevertheless, we further determined the inhibitory expression level of MHC class II tetramer+ HCV-specific CD4+ T cells longitudinally of 4 chronic HCV infected patients who received DAA therapy. We could not detect any difference of the inhibitory expression level percentage-wise at any time point after DAA initiation (data not shown). However, we observed a large and significant drop of the PD-1 and TIGIT mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) on HCV–specific CD4+ T cells of all patients after DAA therapy initiation (Suppl. 4A–C). Furthermore, we investigated the MFI of TIGIT, PD-1, and CD226 on HCV–specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells in longitudinal samples from the acute patients aHCV1 and aHCV6 who later progressed to chronic infection and were eventually antivirally treated with PEG-IFN during the acute phase, as well as of patient aHCV4 who spontaneously eliminated the virus (Suppl. 5A,B). As expected, we could detect a decrease of the PD-1 MFI after HCV therapy initiation while the TIGIT MFI slightly decreased. In patient aHCV4 who spontaneously resolved the acute HCV infection, an even more profound parallel drop of PD-1 and TIGIT could be observed (Suppl. 5A,B).

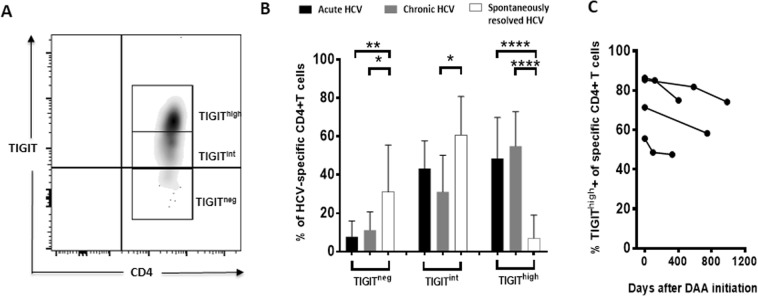

HCV–specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells are predominantly TIGIThigh in patients with acute and chronic HCV infection

Since it was previously reported that HIV-specific TIGIThigh CD4+ T cells (that is TIGIT+ T cells with high MFI) were especially negatively correlated with polyfunctionality and displayed a diminished expression of CD22645. We next investigated the MFI of TIGIT expression on CD4+ T cells of HCV patients with different disease stage (Fig. 5A–C). To this aim, we divided the MHC class II tetramer+ HCV-specific CD4+ T cells into subpopulations (hi/int/neg) based on the intensity of TIGIT expression (Fig. 5A). Here, we observed that TIGIThigh cells were significantly more frequent in patients with acute and chronic compared to patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection (acute vs. resolved: p = <0,0001, chronic vs. resolved: p = <0,0001) (Fig. 5B). In contrast, only a small fraction of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of acutely and chronically infected patients were TIGITint or TIGITneg45. Subsequently, we investigated whether there was any difference in the frequency of TIGIThigh CD4+ T cells in longitudinal samples during DAA therapy of four chronic HCV infected patients (Fig. 5C). The frequency of TIGIThigh HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells decreased after DAA initiation in all four patients, but remained at a higher level compared to the TIGIThigh frequency of spontaneously resolved patients. The results might indicate that not only the overall frequency of TIGIT cells, but rather the intensity of the expression of this co-inhibitory molecule influences the T cell functionality and a similar observation has been made in HIV infection45.

Figure 5.

(A–C) Ex vivo frequency of HCV–specific TIGIThigh and TIGITint CD4+ T cells of HCV patients with acute, chronic and spontaneously resolved infection and longitudinally during DAA therapy. (A) Depicting the gating strategy of HCV-specific MHC class II tetramer+ CD4+ T cells divided into subpopulations (TIGIThigh/int/neg) based on the intensity of TIGIT expression and (B) the frequency of TIGIThigh and TIGITint T cells of patients with acute, chronic and spontaneously resolved HCV infection. (C) The TIGIThigh frequency of HCV–specific CD4+ T cells was analysed in longitudinal samples of chronic HCV patients before, during and after DAA therapy. P values were calculated by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. P-values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant, where *,** and *** indicate p-values between 0.01 to 0.05, 0.001 to 0.01 and 0.0001 to 0.001 respectively.

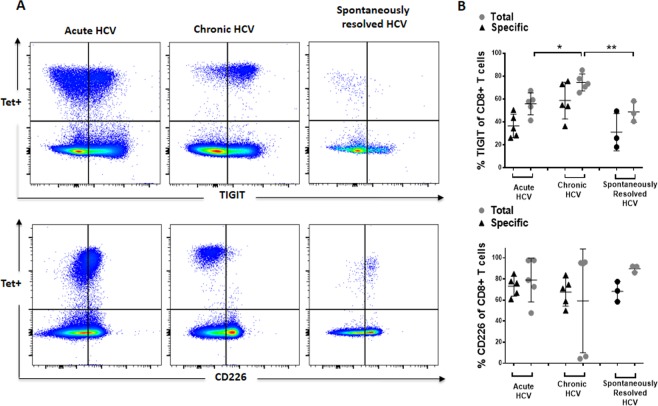

Definition of the expression pattern of the TIGIT/CD226 axis of HCV-specific CD8+ T cells at different stages of infection

TIGIT has previously been described as an exhaustion marker of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells18,21. The co-inhibitory phenotype of MHC class I + II tetramer+ virus–specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in HCV infection has rarely been studied side-by-side. We conducted additional preliminary experiments to also understand the expression pattern of our panel of co-inhibitory markers and TIGIT of HCV-specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6A–C, Suppl. 6 and data not shown). Of note, the expression pattern differed between HCV-specific MHC class I/II tetramer+ CD8+ and CD4+ T cells: TIGIT expression level of MHC class I HCV-specific CD8+ T cells was generally lower in acute and spontaneously resolved HCV infection but much higher in patients with chronic (chronic vs acute: p = 0,0162, chronic vs resolved: p = 0,0056) HCV infection (Fig. 6A,B). The expression of CD226 on MHC class I tetramer+ HCV-specific CD8+ T cells was variable in chronic HCV infection (Fig. 6C). Three chronically infected patients expressed CD226 at an intermediate level, however two patients showed a complete downregulation of this molecule. Of note, the patients who expressed CD226 at an intermediate level were all HLA-A*02.01 and the other HLA-A*24:02. However, sequence of the circulating virus was not available and viral escape might be a possible explanation for this finding.

Figure 6.

(A,B) Ex vivo TIGIT and CD226 expression of HCV–specific CD8+ T cells of patients with acute, chronic and spontaneously resolved HCV infection. Representative dot plots depicting the inhibitory receptor expression of HCV-specific MHC class I tetramer+ CD8+ T cells of patients with acute, chronic and spontaneously resolved HCV infection. Comparison of the TIGIT and CD226 frequency of total and HCV-specific CD8+ T cells of HCV patients with acute, chronic and spontaneously resolved HCV infection. P-values were calculated using one-way ANOWA, followed by Tukey’s multiply comparisons test. P-values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant, where *,** and *** indicate p-values between 0.01 to 0.05, 0.001 to 0.01 and 0.0001 to 0.001 respectively.

Discussion

Virus-specific CD4+ T cells are primed during acute HCV infection regardless of the outcome but seem to have proliferative defects in patients with chronically evolving disease, and the HCV-specific T cell response wanes further over time1,6,46–48. It is generally believed that the reason for this dysfunction is immune exhaustion, a mechanism that has been well-described for CD8+ T cells in murine models and different human chronic viral infections and which is associated with reduced cytokine production, impaired proliferate potential and an upregulation of different co-inhibitory molecules on T cells31,49. Recently, Johnston et al. (2014) identified a critical role for TIGIT in regulating exhausted CD8+ T cell responses in cancer and chronic infections and additionally identified the TIGIT/CD226 pathway, which provides significant interest for a combined blockade with the PD-1 pathway in order to strengthen the CD8+ T cell response17. Indeed, several groups could show that in vitro blockade of the TIGIT pathway reinvigorates the exhausted T cell response and first clinical trials in cancer are underway50.

In the current study, we studied the co-inhibitory marker expression pattern of CD4+ T cells and could show that TIGIT expression was upregulated on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of patients with acute and chronic HCV infection compared to patients who spontaneously resolved the HCV infection. The TIGIT expression was closely linked to the co-expression of the inhibitory receptors PD-1 and TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells seemed to be the best combination of co-inhibitory markers to discriminate patients with acute and chronic disease versus spontaneous resolution of HCV, and we observed a significant decrease of TIGIT and PD-1 MFI after antiviral HCV therapy. TIGIT’s complementary receptor CD226 was downregulated on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells in chronically HCV infected patients and of particular interest, slightly increased after antiviral HCV therapy initiation.

Viral clearance of the chronic strain of LCMV in mice by combined blockade of TIGIT and PD-L1 provided the first evidence of the advantages of targeting these two pathways17. In addition, targeting TIGIT and PD-L1 on tumour-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in patients with advanced melanoma synergistically improves potent anti-tumour responses18. Here, we could detect an elevated PD-1/TIGIT co-expression on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of acutely and chronically infected patients compared to patients with spontaneously resolved infections. In addition, the PD-1/TIGIT co-expression remained elevated despite antigen removal due to successful antiviral therapy with sustained virologic response (SVR), indicative of only a partial recovery of the HCV-specific T cell response in these patients. Indeed, it is widely known that spontaneously resolved HCV infection partly protects patients of developing a chronic course during a re-infection, which is not the case in re-infected HCV patients with a former SVR by therapy1,51.

Furthermore, we investigated whether there is any difference of the TIGIT/PD-1 co-expression during early acute HCV infection between patients who later progressed to either chronic infection versus spontaneous resolution of the HCV infection. We detected a slight statistical trend of a lower TIGIT/PD-1 frequency on HCV–specific CD4+ T cells in the patient group that later resolved the HCV infection. This difference did not reach statistical significance and larger cohorts are needed to investigate whether TIGIT/PD-1 expression could serve as a predictive biomarker combination for clinical outcome. Our phenotypic data would fit the results of previous studies that found that especially high intensity of TIGIT expression together with PD-1 marks dysfunctional T cells45.

Intriguingly, Johnston et al. found TIGIT’s immunomodulatory effects also depend on CD226 expression17. Previous studies have shown a perturbed TIGIT/CD226- axis for virus-specific T cells in HIV infected individuals45. Our study aligns well with these previous observations. Here, we observed a reduced CD226 expression level of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells in patients with chronic HCV infection compared to patients with spontaneously resolved HCV infection. The competition for the ligand could partially explain this shifted TIGIT/CD226 axis. In particular, TIGIT’s ability to interfere with CD226 signalling by physically preventing homodimerization represents an important mechanism by which inhibitory receptors can exert their immunomodulatory effects29,52. Of note, during acute HCV infection CD226 was decreased on HCV-specific CD4+ T cells of patients who progressed later to chronic HCV infection. This might indicate that the expression of the co-stimulatory receptor CD226 could potentially serve as a prediction marker of spontaneous HCV eradication. Likewise, we observed a slight -but significantly- higher CD226 expression of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells in patients with SVR after antiviral HCV therapy for chronic infection. Recent genome-wide association studies revealed susceptibility variants of polymorphisms in the CD226 gene in distinct autoimmune diseases leading to reduced CD226 cell-surface in distinct T cell subsets53. In follow-up studies, we will try to elucidate this complex relationship of CD226 expression with T cell activation and exhaustion.

We also extended the analysis of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells and compared the TIGIT and CD226 expression of HCV-specific CD4+ versus CD8+ T cells of acutely and chronically versus HCV patients with spontaneous resolution of infection. In line with prior studies, we could detect a significant increase of TIGIT expression on HCV-specific CD8+ T cells of patients with chronic HCV infection compared to patients with acute and spontaneously resolved HCV infection. However, it is important to note that the co-inhibitory expression pattern differed somewhat between HCV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. For example, TIGIT expression on HCV MHC class I tetramer+ CD8+ T cells was low during the acute infection and higher levels were only detectable on HCV-specific CD8+ T cells in chronically infected patients. It is intriguing to speculate whether indeed the virus-specific CD4+ cells exhaust faster than the corresponding HCV-specific CD8+ T cells1,54,55.

Our study is one of the most detailed phenotypic immunological studies of co-inhibitory molecule expression of HCV-specific CD4+ in parallel with CD8+ T cells in patients at different stages of HCV using MHC class I + II tetramers to date. However, this study has certain shortcomings inherent of translational cohort studies. We were limited in terms of number of cells, the number of antibodies that could be stained in one individual FACS panel and only basic memory subpopulations were analysed, the patient groups were rather small; and patients were antivirally treated with the different HCV drug regimens (some patients were still treated with interferon-based regimens). Also, patients had different HCV genotypes and sequences of circulating virus were not available and the presence of possible viral escape mutations was not formally tested for the respective epitopic regions and HCV-specific tetramer responses.

In summary, our findings confirm TIGIT together with PD-1 as a potential novel signature marker combination of dysfunctional HCV-specific CD4+ T cells and suggest that TIGIT along with other checkpoint receptors may be a curative target to reverse T cell exhaustion in chronic viral diseases or cancer.

Material and Methods

Patient cohort

PBMC of HCV infected patients (n = 39) and of uninfected healthy controls (n = 10) were collected at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf and stored in liquid nitrogen (−196 °C). Written informed consent was given by all patients and the study was approved by the local ethics board of the Ärztekammer Hamburg WF14-09, PV4780, PV4081, and all experiments were performed in accordance to relevant guidelines and regulations. Table 1 shows the detailed clinical, virologic and immunological information of 29 patients who were further stratified into 4 groups according to their disease stage56 in acute HCV (n = 10), chronic HCV (n = 11), SVR (n = 4) and spontaneously resolved HCV (n = 8) whose PBMC were used for further detailed phenotypic ex vivo MHC class I + II tetramer analysis.

HLA typing

High definition molecular HLA class I and II typing were performed at the Institute of Transfusion Medicine at University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf by polymerase chain reaction-sequence specific oligonucleotide (PCR-SSO) using the commercial kit SSO LabType (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA, USA)57.

MHC class I and MHC class II tetramer staining and enrichment

HCV-specific MHC class I and II tetramers used in this study are shown in Table II. MHC class I and class II tetramer-associated magnetic bead enrichment technique was performed as previously described42. Briefly, cryopreserved PBMC were thawed and stained with PE-labeled HLA class I or class II matching tetramers. Tetramer-enrichment was performed with anti-PE microbeads applying MACS technology (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Pre-, enriched and depleted Tetramer fractions were further analysed by flow cytometry using BD LSRFortessa™. Frequencies of virus-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells were calculated as previously described42.

Multiparametric flow cytometry

For multiparametric flow cytometry analysis, PBMC were stained and enriched with the matched MHC class I or class II tetramer. To exclude dead cells in the subsequent analysis, PBMC were stained with the LIVE/DEAD™ Fixable Near-IR dye (Thermo Fisher, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PBMC were stained with appropriate fluorochrome-conjugated surface antibodies, including anti-CD3 (OKT3), anti-CD4 (RPA-T4) anti-CD45RO (UCHL1), anti-CCR7 (G043H7), anti-CD226 (DX11), anti-TIGIT (A15153G), anti-BTLA (MIH26), anti-LIGHT (115520), anti-Ceacam1 (ASL-32), anti-Tim-3 (F38-2E2), anti-PD-1 (EH12.2H7), anti-OX40 (ACT-35), anti-CD14 (63D3), anti-CD19 (HIB19) (from Biolegend, Koblenz or BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) for 20 min at RT in the dark. After surface staining, cells were washed once with PBS and were then resuspended in 0.5% paraformaldehyde.

Statistical analysis

All flow cytometric data were analysed using FlowJo version 10.4.2 software (Treestar, Ashland, OR, USA). Statistical analysis was carried out using Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). All groups were tested for normal distribution with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and were compared by the adequate test. For normally distributed data, parametric tests were applied: for two groups the t-test was used, for more than two groups a ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used. Data that was not normally distributed was tested by the Mann-Whitney test for two unpaired groups, by the Wilcoxon test for paired groups, or Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for more than two groups, respectively. P-values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant, where *,** and *** indicate p-values between 0.01 to 0.05, 0.001 to 0.01 and 0.0001 to 0.001, respectively. Data are expressed as means with standard deviation, respectively (as indicated in the figure legend). Statistical analysis and display of multicomponent distributions was performed with SPICE v5.143.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients who participated in this study. We thank Johann von Felden and Felix Piecha for helping with recruitment of patients. Janna Heide helped with staining of samples. This work was supported by the German Research Agency (J.S.Z.W., A.W.L., J.B., C.A., V.M., C.S., M.L., G.D.A.; SFB841 project A6; T.B. TRR179-TP04). J.S.z.W., A.W.L. and T.B. are supported by the German Center for Infection, DZIF. Preliminary data were presented as abstracts at the EASL2018 and GASL 2018.

Author Contributions

J.S.z.W., T.B. and C.A. designed the study. J.S.z.W., A.W.L. and T.B. gave institutional support. C.A., R.W. and S.K. conducted experiments. T.K., T.B. and J.S.z.W. recruited the patients and M.S. helped to establish the enrichment technique. B.W.K. contributed reagents. C.A. analysed the data and J.M.E. contributed to the interpretation of the multicolor flow panels. S.P. and M.M. supervised and analysed the HLA-typing. C.A. and J.S.z.W. wrote the first draft of manuscript. C.A. prepared the figures and got input from J.S.Z.W., T.J. and all other authors. All authors reviewed the manuscript and gave important input.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-47024-8.

References

- 1.Schulze Zur Wiesch J, et al. Broadly directed virus-specific CD4+ T cell responses are primed during acute hepatitis C infection, but rapidly disappear from human blood with viral persistence. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2012;209:61–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thimme R, et al. Determinants of viral clearance and persistence during acute hepatitis C virus infection. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2001;194:1395–1406. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:41–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grebely J, et al. Hepatitis C virus clearance, reinfection, and persistence, with insights from studies of injecting drug users: towards a vaccine. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:408–414. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70010-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey JR, Barnes E, Cox AL. Approaches, Progress, and Challenges to Hepatitis C Vaccine Development. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:418–430. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grakoui A, et al. HCV persistence and immune evasion in the absence of memory T cell help. Science. 2003;302:659–662. doi: 10.1126/science.1088774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shoukry NH, Cawthon AG, Walker CM. Cell-mediated immunity and the outcome of hepatitis C virus infection. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:391–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holz L, Rehermann B. T cell responses in hepatitis C virus infection: historical overview and goals for future research. Antiviral Res. 2015;114:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasprowicz V, et al. High level of PD-1 expression on hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells during acute HCV infection, irrespective of clinical outcome. Journal of virology. 2008;82:3154–3160. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02474-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urbani S, et al. PD-1 expression in acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is associated with HCV-specific CD8 exhaustion. Journal of virology. 2006;80:11398–11403. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01177-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kroy DC, et al. Liver environment and HCV replication affect human T-cell phenotype and expression of inhibitory receptors. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:550–561. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duggal P, et al. Genome-wide association study of spontaneous resolution of hepatitis C virus infection: data from multiple cohorts. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:235–245. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bengsch B, et al. Coexpression of PD-1, 2B4, CD160 and KLRG1 on exhausted HCV-specific CD8+ T cells is linked to antigen recognition and T cell differentiation. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000947. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlaphoff V, et al. Dual function of the NK cell receptor 2B4 (CD244) in the regulation of HCV-specific CD8+ T cells. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002045. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seder RA, Ahmed R. Similarities and differences in CD4+ and CD8+ effector and memory T cell generation. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:835–842. doi: 10.1038/ni969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teigler, J. E. et al. Differential Inhibitory Receptor Expression on T Cells Delineates Functional Capacities in Chronic Viral Infection. Journal of virology 91 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Johnston RJ, et al. The immunoreceptor TIGIT regulates antitumor and antiviral CD8(+) T cell effector function. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:923–937. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chauvin JM, et al. TIGIT and PD-1 impair tumor antigen-specific CD8(+) T cells in melanoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2046–2058. doi: 10.1172/JCI80445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Catakovic K, et al. TIGIT expressing CD4+ T cells represent a tumor-supportive T cell subset in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncoimmunology. 2017;7:e1371399. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1371399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillerey, C. et al. TIGIT immune checkpoint blockade restores CD8(+) T cell immunity against multiple myeloma. Blood (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Chew GM, et al. TIGIT Marks Exhausted T Cells, Correlates with Disease Progression, and Serves as a Target for Immune Restoration in HIV and SIV Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005349. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hung AL, et al. TIGIT and PD-1 dual checkpoint blockade enhances antitumor immunity and survival in GBM. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1466769. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1466769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boettler T, et al. Exogenous OX40 stimulation during lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection impairs follicular Th cell differentiation and diverts CD4 T cells into the effector lineage by upregulating Blimp-1. J Immunol. 2013;191:5026–5035. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boettler T, et al. OX40 facilitates control of a persistent virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002913. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golden-Mason L, et al. Negative immune regulator Tim-3 is overexpressed on T cells in hepatitis C virus infection and its blockade rescues dysfunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Journal of virology. 2009;83:9122–9130. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00639-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sen DR, et al. The epigenetic landscape of T cell exhaustion. Science. 2016;354:1165–1169. doi: 10.1126/science.aae0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rutebemberwa A, et al. High-programmed death-1 levels on hepatitis C virus-specific T cells during acute infection are associated with viral persistence and require preservation of cognate antigen during chronic infection. J Immunol. 2008;181:8215–8225. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamoto N, et al. Synergistic reversal of intrahepatic HCV-specific CD8 T cell exhaustion by combined PD-1/CTLA-4 blockade. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000313. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pauken KE, Wherry EJ. TIGIT and CD226: tipping the balance between costimulatory and coinhibitory molecules to augment the cancer immunotherapy toolkit. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:785–787. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cella M, et al. Loss of DNAM-1 contributes to CD8+ T-cell exhaustion in chronic HIV-1 infection. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:949–954. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wherry EJ, Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:486–499. doi: 10.1038/nri3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin HT, et al. Cooperation of Tim-3 and PD-1 in CD8 T-cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14733–14738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009731107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richter K, Agnellini P, Oxenius A. On the role of the inhibitory receptor LAG-3 in acute and chronic LCMV infection. Int Immunol. 2010;22:13–23. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Welch MJ, Teijaro JR, Lewicki HA, Colonna M, Oldstone MB. CD8 T cell defect of TNF-alpha and IL-2 in DNAM-1 deficient mice delays clearance in vivo of a persistent virus infection. Virology. 2012;429:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaye J. CD160 and BTLA: LIGHTs out for CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:122–124. doi: 10.1038/ni0208-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owusu Sekyere S, et al. A heterogeneous hierarchy of co-regulatory receptors regulates exhaustion of HCV-specific CD8 T cells in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2015;62:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golden-Mason L, et al. Upregulation of PD-1 expression on circulating and intrahepatic hepatitis C virus-specific CD8+ T cells associated with reversible immune dysfunction. Journal of virology. 2007;81:9249–9258. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00409-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barathan M, et al. CD8+ T cells of chronic HCV-infected patients express multiple negative immune checkpoints following stimulation with HCV peptides. Cell Immunol. 2017;313:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abel A, et al. Differential expression pattern of co-inhibitory molecules on CD4(+) T cells in uncomplicated versus complicated malaria. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4789. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22659-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raziorrouh B, et al. Inhibitory phenotype of HBV-specific CD4+ T-cells is characterized by high PD-1 expression but absent coregulation of multiple inhibitory molecules. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fromentin R, et al. CD4+ T Cells Expressing PD-1, TIGIT and LAG-3 Contribute to HIV Persistence during ART. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005761. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Day CL, et al. Ex vivo analysis of human memory CD4 T cells specific for hepatitis C virus using MHC class II tetramers. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:831–842. doi: 10.1172/JCI200318509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roederer M, Nozzi JL, Nason MC. SPICE: exploration and analysis of post-cytometric complex multivariate datasets. Cytometry A. 2011;79:167–174. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.21015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu X, et al. The surface protein TIGIT suppresses T cell activation by promoting the generation of mature immunoregulatory dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:48–57. doi: 10.1038/ni.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tauriainen J, et al. Perturbed CD8(+) T cell TIGIT/CD226/PVR axis despite early initiation of antiretroviral treatment in HIV infected individuals. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40354. doi: 10.1038/srep40354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diepolder HM, et al. Possible mechanism involving T-lymphocyte response to non-structural protein 3 in viral clearance in acute hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet. 1995;346:1006–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91691-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang KM, et al. Differential CD4(+) and CD8(+) T-cell responsiveness in hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2001;33:267–276. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Day CL, et al. Broad specificity of virus-specific CD4+ T-helper-cell responses in resolved hepatitis C virus infection. Journal of virology. 2002;76:12584–12595. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12584-12595.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:492–499. doi: 10.1038/ni.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Solomon BL, Garrido-Laguna I. TIGIT: a novel immunotherapy target moving from bench to bedside. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1659–1667. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2246-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ingiliz P, et al. HCV reinfection incidence and spontaneous clearance rates in HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Western Europe. J Hepatol. 2017;66:282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fourcade, J. et al. CD226 opposes TIGIT to disrupt Tregs in melanoma. JCI Insight3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Gross CC, et al. Haplotype matters: CD226 polymorphism as a potential trigger for impaired immune regulation in multiple sclerosis REPLY. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E908–E909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619059114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crawford A, et al. Molecular and transcriptional basis of CD4(+) T cell dysfunction during chronic infection. Immunity. 2014;40:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brooks DG, McGavern DB, Oldstone MB. Reprogramming of antiviral T cells prevents inactivation and restores T cell activity during persistent viral infection. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1675–1685. doi: 10.1172/JCI26856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mosbruger TL, et al. Large-scale candidate gene analysis of spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1371–1380. doi: 10.1086/651606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.da Costa Lima Caniatti MC, Borelli SD, Guilherme AL, Tsuneto LT. Association between HLA genes and dust mite sensitivity in a Brazilian population. Hum Immunol. 2017;78:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.