Summary

In recent months there has been a wealth of promising clinical data suggesting that a more effective treatment regimen, and potentially a cure, for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is close at hand. Leading this push are direct acting antivirals (DAAs), currently comprised of inhibitors that target the HCV protease NS3, viral polymerase NS5B and the nonstructural protein NS5A. In combination with one another, along with the traditional standard of care ribavirin and PEGylated-IFNα, these compounds have proven to afford tremendous efficacy to treatment-naïve patients, as well as to prior non-responders. Nevertheless, by targeting viral components the possibility of selecting for breakthrough and treatment-resistant virus strains remains a concern. Host-targeting antivirals (HTAs) are a distinct class of anti-HCV compounds that is emerging as a complementary set of tools to combat the disease. Cyclophilin (Cyp) inhibitors are one such group in this category. In contrast to DAAs, Cyp inhibitors target a host protein, CypA, and have also demonstrated remarkable antiviral efficiency in clinical trials, without the generation of viral escape mutants. This review serves to summarize the current literature on cyclophilins and their relationship to the HCV viral life cycle, as well as other viruses.

HCV is the major causative agent of acute and chronic liver diseases (Dienstag and McHutchison, 2006). Primary infection is often asymptomatic or associated with mild symptoms, whereas persistently infected individuals exhibit a high risk for chronic liver diseases, such as hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis (Dienstag and McHutchison, 2006). Nearly 200 million people worldwide (3% of the population), including 4 to 5 million in the US, are chronically infected with HCV and 4 million new infections occur every year (Alter, 2007; Soriano et al., 2008). In the developed world, HCV accounts for two-thirds of all cases of liver cancer and transplants (Shepard et al., 2005), and, in the US, approximately 12,000 people are estimated to die from HCV each year (Armstrong et al., 2006). There is no vaccine for HCV and current new therapeutics have focused upon inhibition of viral enzymes and proteins; however, the high rate of mutation associated with the virus-encoded RNA polymerase has been shown to afford escape mutants that are resistant to these compounds. Thus, efficient treatment and eradication of HCV will likely require the concerted targeting and disruption of a number of critical virus-host interactions, coupled with the suppression of viral enzymatic activities.

Introduction

In humans, there are three distinct families of peptidyl-prolyl isomerases (PPIases), also referred to as immunophilins: Cyps, FK506-binding proteins (FKBPs), which bind the immunosuppressant FK506, and the parvulin family (Galat, 2004). The three PPIase families are unrelated in sequence and three-dimensional structure; however, all catalyze the cis/trans isomerization of the peptide bond on the N-terminal side of proline residues in proteins (Fischer and Aumuller, 2003). Typically, this PPIase activity serves to function as a chaperone to drive proper protein folding, as well as conformational changes necessary for functionality, evidenced by a number of early studies that looked at the role of cis/trans isomerization of the petidyl-prolyl bond during variable protein refolding conditions (Schmid, 1993).

CypA is an abundant, cytosolic 18kDa protein that is found in all human tissues, it was also the first Cyp to be identified via its ability to bind to cyclosporine A (CsA) (Handschumacher et al., 1984). Around the same time, PPIase activity was identified by Fischer et al. (Fischer et al., 1984); however, it was another 5 years before the connection between CypA and PPIase activity was made (Fischer et al., 1989; Takahashi et al., 1989). CypA is the prototypical member of the Cyp family, as it is essentially comprised of the defining characteristic of this group of enzymes, a Cyp-like domain (CLD), which encompasses the entire region of PPIase activity. Homologs of CypA and other Cyp family members are highly conserved and can be found in all domains of life from archaea and bacteria, all the way up to eukaryotes (Galat, 2004; Wang and Heitman, 2005).

Twenty distinct Cyp ORFs have been detected in humans, nearly half of which encode single domain proteins that are primarily comprised of the CLD (Galat and Bua, 2010). The remaining ORFs are multidomain Cyp family members that encode variable domains surrounding the CLD, which serve to confer a diverse array of activities such as intracellular targeting, RNA recognition, and protein-protein interactions (Galat and Bua, 2010). Diversity of functional activity within the Cyp family is partially attributable to the localization of human Cyps, as they are localized in the cytoplasm, nucleus, ER, mitochondria, and attached to various membranes (Galat, 2004; Wang and Heitman, 2005). For example, a number of nuclear Cyps - CypE, CypG, CypH, CypJ and Cyp60 - remain within the nucleus where they are engaged in spliceosome formation and function (Mesa et al., 2008), whereas RanBP2, the largest member of the Cyp family (~360kDa), functions in the nuclear membrane and acts as a nucleoporin (Galat and Bua, 2010). In the mitochondria, CypD has been shown to be a major component of the mitochondrial permeabilization transition pore, where it plays an intricate role in mitochondrial-mediated cell death (Nakagawa et al., 2005; Schinzel et al., 2005).

A link between PPIase function and modern medicine arose prior to the discovery of PPIase activity, as it was discovered in the 1970s that the introduction of the chemical inhibitors cyclosporine A (CsA) and FK506 dramatically decreased immune-mediated tissue graft rejection, thereby revolutionizing organ transplantation (Calne et al., 1978; Starzl et al., 1981). The immunosuppressive activity associated with these compounds was later linked to the ability of Cyp-CsA and FKBP-FK506 complexes to bind and block the phosphatase activity of calcineurin, which in turns prevents the dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activating T cells (NF-AT), thereby preventing nuclear translocation of NF-AT and subsequent cytokine transcriptional activation (Gothel and Marahiel, 1999). Modern medical Cyp research has largely focused upon the role of Cyps in viral infection, reviewed below. It is important to note that Cyps have also been found to play a role in a wide range of diseases and cellular dysfunctions such as cancer, angiogenesis, atherosclerosis, ER stress, and neurodegeneration (Lee and Kim, 2010).

Cyclophilins and the Hepatitis C Virus

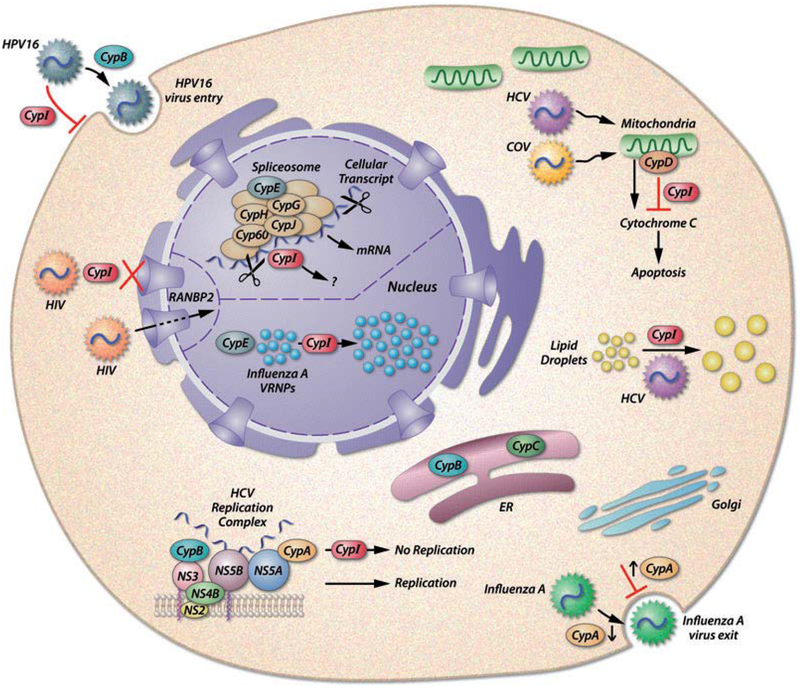

In 2003, a groundbreaking study by Watashi et al. revealed that HCV replication in a cell culture model was severely impeded by the introduction of the chemical Cyp inhibitors CsA and NIM811 (Watashi et al., 2003). With the growing health burden and lack of viable treatment options for HCV, the pharmaceutical industry took notice and spent considerable time and energy in further developing nonimmunosuppressive Cyp inhibitors that would be more readily tolerated in prospective patients. A number of these compounds have reached variable phases of clinical trials, the most successful of which is Alisporivir (Gallay, 2011). Importantly, clinical trails have recently shown that Cyp inhibitors are capable of suppressing HCV in as little as two weeks when combined with ribavirin and PEGylated-IFNα (Lawitz et al., 2011), while monotherapy of Alisporivir alone was effective at combatting HCV genotype 3 (Sarin and Kumar, 2012). To date, the exact mechanism of action in which these compounds affect HCV replication remains unclear, despite the fact that a number of Cyp-HCV protein interactions have been elucidated. It is also known that chemical Cyp inhibitors are capable of acting upon many of the Cyp family members that are present throughout the cell, demonstrated in Figure 1. Generally, it could be reasoned that since many of the single domain Cyps function as chaperones that serve to monitor polypeptide folding fidelity, subsequent disruption of this activity through Cyp binding to the chemical inhibitor could elicit a state of distress within the ER, a cellular machine to which the HCV life cycle is critically linked. The tolerance of healthy tissues and overall patient health in response to large doses of these compounds, suggests that any distress created by Cyp inhibition is minimal or temporary to noninfected cells.

Figure 1. Cellular Localization of Cyps-Virus Interactions.

A variety of published Cyp-Virus interactions are illustrated to demonstrate the breadth and diversity of cellular and viral outcomes imparted by chemical Cyp inhibitors (CypI, in red above). Adapted from Gaither et al. 2010.

The role of Cyps in the HCV life cycle has been intensively investigated for the better part of the last decade. The majority of this research has focused upon evaluating what Cyp family members are involved in HCV replication, which viral proteins interact directly with Cyps, and what viral escape mutations arise during selection for drug resistance. From a number of studies it is clear that CypA is required for HCV replication and likely the primary target for chemical inhibitors, as evidenced through knockdown assays performed by a number of groups (Chatterji et al., 2009; Gaither et al., 2010; Hanoulle et al., 2009; Kaul et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2008). Importantly it was also shown that a functional hydrophobic pocket in CypA is necessary for HCV replication, which strongly suggested that the chaperone function or isomerase activity of CypA is essential for HCV genotype 1b (GT-1b) amplification in a cell culture (Chatterji et al., 2009; Kaul et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2009b). The existence of CypA knockout mice and stable CypA knockdown cell lines indicates that CypA is not required for cell growth and survival, which in turn suggests that the treatment of HCV-infected patients with Cyp inhibitors should not lead to major drug complications (Braaten and Luban, 2001; Colgan et al., 2005).

Multiple studies have shown that CypA interacts directly with NS5A of multiple genotypes, and importantly this binding is abrogated by the presence of a variety of chemical Cyp inhibitors (Chatterji et al., 2010; Coelmont et al., 2010; Fernandes et al., 2010; Foster et al., 2011; Gregory et al., 2011; Hanoulle et al., 2009; Verdegem et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2010). Recently, elaborate nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy studies have revealed that CypA binds directly to a number of proline residues within domains II and III of the NS5A protein of multiple HCV genotypes (Coelmont et al., 2010; Hanoulle et al., 2009; Verdegem et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2010). These studies showed that CypA bound to these proline residues via the enzymatic pocket of the CLD, and was capable of inducing a cis/trans isomerization in many of these sites (Coelmont et al., 2010; Hanoulle et al., 2009; Verdegem et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2010). A number of studies have identified mutations in the NS5A region of HCV that arise during selection for Cyp-inhibitor escape mutants in replicon cell lines (Chatterji et al., 2010; Fernandes et al., 2007; Goto et al., 2009; Kaul et al., 2009; Puyang et al., 2010). The most common mutation is the D320E amino acid substitution within the NS5A protein; this alteration has been identified by many groups and shown to confer moderate drug resistance when substituted back into a wild-type background (Chatterji et al., 2010; Goto et al., 2009; Puyang et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010). Curiously, NS5A carrying the D320E mutation is still capable of binding CypA and this interaction remains sensitive to chemical disruption, suggesting that HCV resistance to Cyp inhibitors is not dependent upon the affinity of CypA for NS5A (Chatterji et al., 2010; Coelmont et al., 2010). Of interest, NMR analysis of GT-1b NS5A peptides that contain the D320E mutation displayed a markedly distinct cis/trans configuration when compared to the wild-type (Coelmont et al., 2010). Similarly, CD analysis of peptides with the common Cyp inhibitor resistant mutations found in the GT-2a NS5A of HCV genotype 2A, D316E/Y317N, were also found to induce a conformational change, further implicating a role for alternative native protein folding as a means for Cyp inhibitor resistance (Yang et al., 2010). It has also been recently shown that the interaction of domain II of NS5A with functional CypA stimulated NS5A RNA binding capacity when compared to a CypA isomerase-deficient mutant, suggesting a potential role for the PPIase activity of CypA in the folding and functionality of NS5A (Foster et al., 2011).

A number of studies have shown that both CypA and CypB are present in HCV replication complexes, as each is capable of binding to the HCV encoded RNA polymerase NS5B (Abe et al., 2009; Chatterji et al., 2009; Watashi et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2008). Importantly, a number of groups have found mutations that arise in NS5B when subgenomic GT-1b HCV replicon cell lines are selected for Cyp inhibitor resistance, with some mutations conferring drug resistance when introduced back into the parental replicon (Fernandes et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2009b; Robida et al., 2007). Nonetheless, the importance and biological function of the Cyp-NS5B interactions remains unclear and is likely being intensively studied. What is known is that knockdown of cellular CypB alone failed to significantly affect HCV replication, suggesting an ancillary role for CypB or the presence of a cellular redundancy that is capable of overcoming this defect, e.g., another Cyp (Kaul et al., 2009; Chatterji et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2008). Notably the Sugawara group recently identified a novel helicase that binds directly to CsA and facilitates the association of HCV NS5B with CypB, offering another link between Cyps and NS5B (Morohashi et al., 2011). Chemical Cyp inhibitors were also shown to dramatically affect full-length genomic HCV replication at the level of NS2 protease activity, and this too was found to be dependent upon CypA (Ciesek et al., 2009). In support of this finding, HCV polyprotein cleavage and processing kinetics were shown to be altered in the presence of Cyp inhibitors, revealing a general protease dysfunction upon dampening of Cyp activity in an infected cell (Kaul et al., 2009). Further work with Cyps and NS2 are likely ongoing and should clarify the exact role of Cyps in the proteolytic processing of the HCV polyprotein.

Aside from the importance of CypA, other Cyps have been shown to play a role in HCV pathogenesis. The Weidman group was able to demonstrate the diversity of Cyps contributing to the HCV life cycle via siRNA, proteomic, and mRNA analysis of Cyp inhibition in HCV replicon cell lines, unveiling important binding partners of CypA, CypB, CypD, CypH, and Cyp40 that contribute to both cellular function and viral replication (Gaither et al., 2010). Additional studies have also revealed that Cyp inhibition, in the context of HCV replication, is capable of having global effects on the cellular protein landscape and subsequent biological functionality of the cell. Specifically, the Weidman group demonstrated that NIM811 treatment of a subgenomic Con1 cell line or JFH1-infected cells resulted in a dramatic doubling in size and decrease in the overall number of lipid droplets (LDs) (Anderson et al., 2011). It was also shown that in the presence of HCV and NIM811, apoB accumulates in defined regions of these enlarged LDs and fails to be secreted, which also correlated to a decrease in viral particle release (Anderson et al., 2011). These changes to lipid and apoB trafficking were then shown to be Cyp-dependent, with silencing of both CypA and Cyp40 resulting in a similar phenotype with respect to LD size and apoB localization (Anderson et al., 2011). Recently, the Piccoli group has shown that Alisporivir is capable of preventing many HCV-induced mitochondrial dysfunctions, including apoptosis (Quarato et al., 2011). Through the use of inducible cell lines the same group was able to demonstrate that Alisporivir treatment prevented the HCV polyprotein-mediated decrease in cell respiration, collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential, overproduction of reactive oxygen species, and mitochondrial calcium overload (Quarato et al., 2011). While it has been known for some time that Cyp inhibitors are capable of binding CypD, thereby preventing the mitochondrial permeability transition and the subsequent pro-apoptotic cascade, this study serves to highlight a hitherto underappreciated, positive, side-effect of Cyp inhibition upon the HCV-infected cell, survival (Quarato et al., 2011). Collectively, all of these studies reveal the complexity and breadth of analysis required to evaluate the intricate connection of Cyps to the HCV life cycle and it is readily apparent that while many questions have been addressed, many more remain unanswered.

Cyclophilins and Other Viruses

The first link between Cyps and viral infection came nearly two decades ago when the Goff group showed that both CypA and CypB were able to bind to the HIV-1 Gag protein; importantly, these interactions could be disrupted by the addition of CsA (Luban et al., 1993). The field gained physiological traction the following year when two groups collectively demonstrated that i) CypA binds to a proline rich region within the capsid (CA) domain of Gag; ii) CypA is specifically incorporated into HIV-1 virions; iii) the CypA-Gag interaction was required for HIV-1 replication in vitro; iv) CsA and the nonimmunosuppressive CsA analog NIM811 were capable of inhibiting HIV-1 replication; and v) CypA virion incorporation could be abrogated by CsA and NIM811 (Franke et al., 1994; Thali et al., 1994). Mutagenesis of both CypA and CypB revealed that the hydrophobic pocket and isomerase activities of each were necessary for HIV-1 CA binding and virion incorporation (Braaten et al., 1997). While the exact contribution, if any, of CypB to HIV-1 pathogenesis has failed to evolve, the importance of CypA has been expanded further. For example, NMR was elegantly used to show that CypA catalyzes cis/trans isomerization of the native HIV-1 CA (Bosco et al., 2002). Followup studies have suggested that CypA participates in the uncoating of the HIV-1 CA core, thereby enabling successful integration of the viral genome (Strebel et al., 2009; Ylinen et al., 2009). CypA has also been shown to interact with HIV-1 viral protein R (Vpr) and to be required for de novo Vpr synthesis (Zander et al., 2003). NMR and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy revealed CypA catalysis of cis/trans isomerization of the N-terminal of Vpr (Solbak et al., 2010).

Interestingly, the Littman group has revealed a role for the CypA-HIV-1 CA interaction in the activation of the innate immune response, as CsA treatment of HIV-1 during infection of dendritic cells (DCs) triggered interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) transcriptional activation (Manel et al., 2010). Since DCs are typically resistant to HIV-1, this work strongly suggests the existence of a CypA- or CA-triggered innate immune sensor, which could not only explain cell permissivity, but could also potentially be exploited as a means to combat HIV-1 (Manel et al., 2010). Recently, the Towers group demonstrated that an additional member of the Cyp family, RanBP2, also interacts with HIV-1 CA through its Cyp-like domain (Schaller et al., 2011). Uniquely, this pairing is impervious to disruption via CsA inhibition (Schaller et al., 2011). In this elegant study, the group was able to demonstrate a concerted role for CypA and RanBP2 in HIV-1 nuclear import, as both mutation of CA as well chemical inhibition of CypA by Cyp inhibitors was shown to separately and distinctly alter nuclear import machinery usage and affect subsequent HIV-1 integration site targeting (Schaller et al., 2011).

An additional link between Cyps and viral capsid proteins was recently discovered when the nucleocapsid protein of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) was found to also interact directly with CypA: bioinformatics, SPR, and structural modeling resulted in nanomolar dissociation constants as well as putative binding sites (Luo et al., 2004). A recent report has linked Cyps to general CoV replication, as CsA was found to inhibit the replication of SARS-CoV, human CoV 229E, and mouse hepatitis virus in cell culture (de Wilde et al., 2011). Of note, CsA inhibited the SARS-CoV replication cycle at an early step that was not disrupted or affected by the knockdown of either CypA or CypB (de Wilde et al., 2011). An additional group identified a number of immunophilins as binding partners to nonstructural protein 1 (Nsp1) of SARS-CoV, and then demonstrated physiological relevance as the SARS-CoV infection and Nsp-1 overexpression were shown to specifically induce the IL-2 and calcineurin/NFAT transcriptional pathways (Pfefferle et al., 2011). The same group then went on to show that all genera of CoVs were CsA sensitive, corroborating the work of the van Hemert group, illustrating a potential role for Cyp inhibitors as a first line of defense against new and emerging CoVs (Pfefferle et al., 2011). Interestingly, a link between CypD and human CoV-induced neuronal-programmed cell death has also been recently uncovered, further demonstrating the complex role of Cyps in the coronavirus life cycle (Favreau et al., 2012).

Cyps have been found to play a role in a variety of other virus life cycles, summarized in Table I and Figure 1. Briefly, the Liu group revealed that CypA is capable of binding to the middle domain of influenza A matrix protein (M1), while depletion of endogenous CypA increased influenza virus infectivity (Liu et al., 2009a). This group has recently shown that CypE is also inhibitory to influenza A replication and transcription via its interaction with nucleoprotein (NP), which correlated to disruption of the viral ribonucleoprotein complex (Wang et al., 2011). In contrast, Cyps facilitate infectivity of human papillomavirus (HPV) types 16 and 18 at two distinct steps - one entails CypB and viral CA association at the point of internalization, while the other is downstream (Bienkowska-Haba et al., 2009). CypB is also involved in the replication of Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), where CypB knockdown and introduction of an isomerase-deficient CypB reduced the ability of JEV to propagate, notably this effect did not occur at point of internalization (Kambara et al., 2011). Work with other flaviviruses revealed a general sensitivity of the group to CsA at the point of viral RNA replication, which correlated with the interaction of CypA to nonstructural protein 5, as well as to the viral RNA itself (Qing et al., 2009). Another connection between CypA and viral replication was demonstrated for a serotype of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), where CsA treatment was shown to inhibit virus production (Bose et al., 2003). Cytomegalovirus replication has also proven to be sensitive to CsA, in yet another example of a viral requirement for Cyps (Kawasaki et al., 2007; Keyes et al., 2012). Data also suggests that Cyp inhibition affects hepatitis B virus (HBV) replication, although the manner in which it does so remains to be determined (Tian et al., 2010; Xia et al., 2005). Interestingly, Cyp homologs in yeast have been shown not to assist but to inhibit the replication of plant viruses in the tombusvirus genus (Mendu et al., 2010).

Table I:

Reported Interactions Between Viral Proteins and Cyps

| Virus Family | Virus | Protein | Cyclophilin | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flaviviridae | HCV | NS2, NS5A, NS5B | CypA, CypB, CypD?, CypH?, Cyp40? | (Fernandes et al., 2010; Gaither et al., 2010; Kaul et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2008) |

| WNV | NS5 | CypA, CypB?, CypC? | (Qing et al., 2009) | |

| JEV | NS4A | CypB | (Kambara et al., 2011) | |

| Dengue | ? | CypA, CypB, CypC | (Qing et al., 2009) | |

| YFV | ? | CypA, CypB | (Qing et al., 2009) | |

| Coronaviridae | SARS-CoV | nucleocapsid | CypA | (Luo et al., 2004) |

| NS protein 1 | CypA, CypB, CypG, CypH, | (de Wilde et al., 2011; Pfefferle et al., 2011) | ||

| All CoV | NS protein 1 | CypA, CypB, CypD?, CypG, CypH | (de Wilde et al., 2011; Favreau et al., 2012; Pfefferle et al., 2011) | |

| Rhabdoviridae | VSV | nucleocapsid | CypA | (Bose et al., 2003) |

| Orthomyxoviridae | Influenza A | M1 | CypA# | (Liu et al., 2009a) |

| nucleoprotein | CypE | (Wang et al., 2011) | ||

| Paramyxoviridae | Measles | N protein | CypA, CypB | (Watanabe et al., 2010) |

| Retroviridae | HIV | Gag | CypA, CypB | (Braaten et al., 1997; Luban et al., 1993) |

| Vpr | CypA | (Solbak et al., 2010; Zander et al., 2003) | ||

| Herpesviridae | CMV | ? | CypA | (Keyes et al., 2012) |

| Papillomaviridae | HPV-16 | capsid | CypB | (Bienkowska-Haba et al., 2009) |

| Poxviridae | Vaccinia | * | CypA* | (Damaso and Keller, 1994) |

| Hepadnaviridae | HBV | surface antigen | CypA | (Tian et al., 2010; Xia et al., 2005) |

| Tombusviridae | Tombusviruses | p33 | Cpr1/CypA homolog# | (Lin et al., 2012; Mendu et al., 2010) |

= Role for cyclophilin shown by RNAi knockdown; interacting viral protein not identified

= Viruses sensitive to Cyp inhibition but with no identification of specific cyclophilin involvement and/or interacting viral protein not identified

= Cyp is inhibitory to virus replication

Taken together these studies demonstrate that multiple Cyps are capable of influencing and affecting numerous steps of highly divergent virus life cycles (Figure 1). The reliance of these virus families upon Cyp activity for such diverse RNA replication pathways, viral entry, internalization, and maturation processes, further highlights the potential impact of Cyp inhibitor therapeutics. Given the apparent broad-spectrum potential of these compounds, the case can be made that Cyp inhibitors could be used as a first line of defense for new and emerging viruses.

Moving Forward

The ability of Cyp inhibitors to afford pan-genotypic anti-HCV activity, coupled with a low incidence of viral breakthrough, makes them an extremely attractive treatment alternative (Flisiak et al., 2012). One can envision cases when the patient presents with a high viral load, where viral breakthrough could readily occur using DAAs alone, such cases would greatly benefit from the addition of an HTA like a Cyp inhibitor. To date, a number of Cyp-virus interactions have been teased apart, yet collectively they fail to fully explain why and how exactly Cyp inhibitors work. Again, the primary function of a Cyp is to serve as a molecular chaperone, presumably to facilitate polypeptide folding and post-translational modification. It is therefore not surprising that Cyps have been found to interact with numerous proteins and subsequently implicated in a wide range of cellular functions. Based upon this global activity one would predict transient, lower affinity interactions between Cyps and target proteins to account for a generalized specificity; however, many high affinity Cyp-ligand interactions have been described. This curious anomaly suggests that perhaps a tightly bound Cyp represents a distinct or regulatable functionality for the molecule. The importance of Cyps in the viral life cycle of other pathogens further implicates a global requirement of complete cellular functionality for optimal viral fitness. Further insight into the changes that occur upon the cellular landscape once a Cyp inhibitor is introduced to a virally-infected cell, is clearly warranted, and could serve to elucidate a precise mechanism of action. It is clear that Cyp inhibitors remain a viable treatment alternative for the elimination of HCV, and possibly other virus families, and the continued basic research upon their molecular mechanism of action should prove to be enlightening in the years to come.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Yves Ribeill for providing the table. We acknowledge financial support from the U.S. Public Health Service grant no. AI087746 (P.A.G.). This is publication no. 21536 from the Department of Immunology & Microbial Science, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA.

References

- Abe K, Ikeda M, Ariumi Y, Dansako H, Wakita T, and Kato N (2009). HCV genotype 1b chimeric replicon with NS5B of JFH-1 exhibited resistance to cyclosporine A. Arch. Virol 154, 1671–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter MJ (2007). Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World J. Gastroentero 13, 2436–2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LJ, Lin K, Compton T, and Wiedmann B (2011). Inhibition of cyclophilins alters lipid trafficking and blocks hepatitis C virus secretion. Virol. J 8, 329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, and Alter MJ (2006). The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann. Intern. Med 144, 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowska-Haba M, Patel HD, and Sapp M (2009). Target cell cyclophilins facilitate human papillomavirus type 16 infection. PLoS Pathog 5, e1000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco DA, Eisenmesser EZ, Pochapsky S, Sundquist WI, and Kern D (2002). Catalysis of cis/trans isomerization in native HIV-1 capsid by human cyclophilin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 99, 5247–5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose S, Mathur M, Bates P, Joshi N, and Banerjee AK (2003). Requirement for cyclophilin A for the replication of vesicular stomatitis virus New Jersey serotype. J. Gen. Virol 84, 1687–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braaten D, Ansari H, and Luban J (1997). The hydrophobic pocket of cyclophilin is the binding site for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag polyprotein. J. Virol 71, 2107–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braaten D, and Luban J (2001). Cyclophilin A regulates HIV-1 infectivity, as demonstrated by gene targeting in human T cells. EMBO J 20, 1300–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calne RY, White DJ, Thiru S, Evans DB, McMaster P, Dunn DC, Craddock GN, Pentlow BD, and Rolles K (1978). Cyclosporin A in patients receiving renal allografts from cadaver donors. Lancet 2, 1323–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji U, Bobardt M, Selvarajah S, Yang F, Tang H, Sakamoto N, Vuagniaux G, Parkinson T, and Gallay P (2009). The isomerase active site of cyclophilin A is critical for hepatitis C virus replication. J. Biol. Chem 284, 16998–17005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji U, Lim P, Bobardt MD, Wieland S, Cordek DG, Vuagniaux G, Chisari F, Cameron CE, Targett-Adams P, Parkinson T, and Gallay PA (2010). HCV resistance to cyclosporin A does not correlate with a resistance of the NS5A-cyclophilin A interaction to cyclophilin inhibitors. J. Hepatol 53, 50–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesek S, Steinmann E, Wedemeyer H, Manns MP, Neyts J, Tautz N, Madan V, Bartenschlager R, von Hahn T, and Pietschmann T (2009). Cyclosporine A inhibits hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 2 through cyclophilin A. Hepatology 50, 1638–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelmont L, Hanoulle X, Chatterji U, Berger C, Snoeck J, Bobardt M, Lim P, Vliegen I, Paeshuyse J, Vuagniaux G, Vandamme AM, Bartenschlager R, Gallay P, Lippens G, and Neyts J (2010). DEB025 (Alisporivir) inhibits hepatitis C virus replication by preventing a cyclophilin A induced cis-trans isomerisation in domain II of NS5A. PLoS One 5, e13687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan J, Asmal M, Yu B, and Luban J (2005). Cyclophilin A-deficient mice are resistant to immunosuppression by cyclosporine. J. Immunol 174, 6030–6038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaso CR, and Keller SJ (1994). Cyclosporin A inhibits vaccinia virus replication in vitro. Arch. Virol 134, 303–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wilde AH, Zevenhoven-Dobbe JC, van der Meer Y, Thiel V, Narayanan K, Makino S, Snijder EJ, and van Hemert MJ (2011). Cyclosporin A inhibits the replication of diverse coronaviruses. J. Gen. Virol 92, 2542–2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienstag JL, and McHutchison JG (2006). American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the management of hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 130, 231–264; quiz 214–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favreau DJ, Meessen-Pinard M, Desforges M, and Talbot PJ (2012). Human coronavirus-induced neuronal programmed cell death is cyclophilin d dependent and potentially caspase dispensable. J. Virol 86, 81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes F, Ansari IU, and Striker R (2010). Cyclosporine inhibits a direct interaction between cyclophilins and hepatitis C NS5A. PloS One 5, e9815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes F, Poole DS, Hoover S, Middleton R, Andrei AC, Gerstner J, and Striker R (2007). Sensitivity of hepatitis C virus to cyclosporine A depends on nonstructural proteins NS5A and NS5B. Hepatology 46, 1026–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer G, and Aumuller T (2003). Regulation of peptide bond cis/trans isomerization by enzyme catalysis and its implication in physiological processes. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol 148, 105–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer G, Bang H, and Mech C (1984). Determination of enzymatic catalysis for the cis-trans-isomerization of peptide binding in proline-containing peptides. Biomed. Biochim. Acta 43, 1101–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer G, Wittmann-Liebold B, Lang K, Kiefhaber T, and Schmid FX (1989). Cyclophilin and peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase are probably identical proteins. Nature 337, 476–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flisiak R, Jaroszewicz J, Flisiak I, and Lapinski T (2012). Update on alisporivir in treatment of viral hepatitis C. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 21, 375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TL, Gallay P, Stonehouse NJ, and Harris M (2011). Cyclophilin A interacts with domain II of hepatitis C virus NS5A and stimulates RNA binding in an isomerase-dependent manner. J. Virol 85, 7460–7464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke EK, Yuan HE, and Luban J, 1994. Specific incorporation of cyclophilin A into HIV-1 virions. Nature 372, 359–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaither LA, Borawski J, Anderson LJ, Balabanis KA, Devay P, Joberty G, Rau C, Schirle M, Bouwmeester T, Mickanin C, Zhao S, Vickers C, Lee L, Deng G, Baryza J, Fujimoto RA, Lin K, Compton T, and Wiedmann B (2010). Multiple cyclophilins involved in different cellular pathways mediate HCV replication. Virology 397, 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galat A (2004). Function-dependent clustering of orthologues and paralogues of cyclophilins. Proteins 56, 808–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galat A, and Bua J (2010). Molecular aspects of cyclophilins mediating therapeutic actions of their ligands Cell Mol. Life Sci 67, 3467–3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallay PA (2011). Cyclophilin inhibitors: a novel class of promising host-targeting anti-HCV agents. Immunologic Res [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothel SF, and Marahiel MA (1999). Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerases, a superfamily of ubiquitous folding catalysts. Cell Mol. Life Sci 55, 423–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto K, Watashi K, Inoue D, Hijikata M, and Shimotohno K (2009). Identification of cellular and viral factors related to anti-hepatitis C virus activity of cyclophilin inhibitor. Cancer Sci 100, 1943–1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory MA, Bobardt M, Obeid S, Chatterji U, Coates NJ, Foster T, Gallay P, Leyssen P, Moss SJ, Neyts J, Nur-e-Alam M, Paeshuyse J, Piraee M, Suthar D, Warneck T, Zhang MQ, and Wilkinson B, 2011. Preclinical characterization of naturally occurring polyketide cyclophilin inhibitors from the sanglifehrin family. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 55, 1975–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschumacher RE, Harding MW, Rice J, Drugge RJ, and Speicher DW (1984). Cyclophilin: a specific cytosolic binding protein for cyclosporin A. Science 226, 544–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanoulle X, Badillo A, Wieruszeski JM, Verdegem D, Landrieu I, Bartenschlager R, Penin F, and Lippens G, (2009). Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein is a substrate for the peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase activity of cyclophilins A and B. J. Biol. Chem 284, 13589–13601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambara H, Tani H, Mori Y, Abe T, Katoh H, Fukuhara T, Taguwa S, Moriishi K, and Matsuura Y (2011). Involvement of cyclophilin B in the replication of Japanese encephalitis virus. Virology 412, 211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul A, Stauffer S, Berger C, Pertel T, Schmitt J, Kallis S, Zayas M, Lohmann V, Luban J, and Bartenschlager R (2009). Essential role of cyclophilin A for hepatitis C virus replication and virus production and possible link to polyprotein cleavage kinetics. PLoS Pathog 5, e1000546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Mocarski ES, Kosugi I, and Tsutsui Y (2007). Cyclosporine inhibits mouse cytomegalovirus infection via a cyclophilin-dependent pathway specifically in neural stem/progenitor cells. J. Virol 81, 9013–9023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes LR, Bego MG, Soland M, and St Jeor S (2012). Cyclophillin A (CyPA) is required for efficient HCMV DNA replication and reactivation. J. Gen. Virol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawitz E, Godofsky E, Rouzier R, Marbury T, Nguyen T, Ke J, Huang M, Praestgaard J, Serra D, and Evans TG (2011). Safety, pharmacokinetics, and antiviral activity of the cyclophilin inhibitor NIM811 alone or in combination with pegylated interferon in HCV-infected patients receiving 14 days of therapy. Antiviral Res 89, 238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, and Kim SS (2010). Current implications of cyclophilins in human cancers. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res 29, 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JY, Mendu V, Pogany J, Qin J, and Nagy PD (2012). The TPR Domain in the Host Cyp40-like Cyclophilin Binds to the Viral Replication Protein and Inhibits the Assembly of the Tombusviral Replicase. PLoS Pathog 8, e1002491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Sun L, Yu M, Wang Z, Xu C, Xue Q, Zhang K, Ye X, Kitamura Y, and Liu W (2009a). Cyclophilin A interacts with influenza A virus M1 protein and impairs the early stage of the viral replication. Cell. Microbiol 11, 730–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Robida JM, Chinnaswamy S, Yi G, Robotham JM, Nelson HB, Irsigler A, Kao CC, and Tang H (2009b). Mutations in the hepatitis C virus polymerase that increase RNA binding can confer resistance to cyclosporine A. Hepatology 50, 25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luban J, Bossolt KL, Franke EK, Kalpana GV, and Goff SP (1993). Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein binds to cyclophilins A and B. Cell 73, 1067–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C, Luo H, Zheng S, Gui C, Yue L, Yu C, Sun T, He P, Chen J, Shen J, Luo X, Li Y, Liu H, Bai D, Shen J, Yang Y, Li F, Zuo J, Hilgenfeld R, Pei G, Chen K, Shen X, and Jiang H (2004). Nucleocapsid protein of SARS coronavirus tightly binds to human cyclophilin A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 321, 557–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manel N, Hogstad B, Wang Y, Levy DE, Unutmaz D, and Littman DR (2010). A cryptic sensor for HIV-1 activates antiviral innate immunity in dendritic cells. Nature 467, 214–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendu V, Chiu M, Barajas D, Li Z, and Nagy PD (2010). Cpr1 cyclophilin and Ess1 parvulin prolyl isomerases interact with the tombusvirus replication protein and inhibit viral replication in yeast model host. Virology 406, 342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesa A, Somarelli JA, and Herrera RJ (2008). Spliceosomal immunophilins. FEBS Lett 582, 2345–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morohashi K, Sahara H, Watashi K, Iwabata K, Sunoki T, Kuramochi K, Takakusagi K, Miyashita H, Sato N, Tanabe A, Shimotohno K, Kobayashi S, Sakaguchi K, and Sugawara F (2011). Cyclosporin A associated helicase-like protein facilitates the association of hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase with its cellular cyclophilin B. PloS One 6, e18285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Shimizu S, Watanabe T, Yamaguchi O, Otsu K, Yamagata H, Inohara H, Kubo T, and Tsujimoto Y (2005). Cyclophilin D-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition regulates some necrotic but not apoptotic cell death. Nature 434, 652–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferle S, Schopf J, Kogl M, Friedel CC, Muller MA, Carbajo-Lozoya J, Stellberger T, von Dall’Armi E, Herzog P, Kallies S, Niemeyer D, Ditt V, Kuri T, Zust R, Pumpor K, Hilgenfeld R, Schwarz F, Zimmer R, Steffen I, Weber F, Thiel V, Herrler G, Thiel HJ, Schwegmann-Wessels C, Pohlmann S, Haas J, Drosten C, and von Brunn A (2011). The SARS-coronavirus-host interactome: identification of cyclophilins as target for pan-coronavirus inhibitors. PLoS Pathog 7, e1002331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puyang X, Poulin DL, Mathy JE, Anderson LJ, Ma S, Fang Z, Zhu S, Lin K, Fujimoto R, Compton T, and Wiedmann B (2010). Mechanism of resistance of hepatitis C virus replicons to structurally distinct cyclophilin inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 54, 1981–1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qing M, Yang F, Zhang B, Zou G, Robida JM, Yuan Z, Tang H, and Shi PY (2009). Cyclosporine inhibits flavivirus replication through blocking the interaction between host cyclophilins and viral NS5 protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 53, 3226–3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarato G, D’Aprile A, Gavillet B, Vuagniaux G, Moradpour D, Capitanio N, and Piccoli C (2011). The cyclophilin inhibitor alisporivir prevents hepatitis C virus-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction. Hepatology [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robida JM, Nelson HB, Liu Z, and Tang H (2007). Characterization of hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicon resistance to cyclosporine in vitro. J. Virol 81, 5829–5840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarin SK, and Kumar CK (2012). Treatment of patients with genotype 3 chronic hepatitis C--current and future therapies. Liver Int 32 Suppl. 1, 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller T, Ocwieja KE, Rasaiyaah J, Price AJ, Brady TL, Roth SL, Hue S, Fletcher AJ, Lee K, KewalRamani VN, Noursadeghi M, Jenner RG, James LC, Bushman FD, and Towers GJ (2011). HIV-1 capsid-cyclophilin interactions determine nuclear import pathway, integration targeting and replication efficiency. PLoS Pathog 7, e1002439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinzel AC, Takeuchi O, Huang Z, Fisher JK, Zhou Z, Rubens J, Hetz C, Danial NN, Moskowitz MA, and Korsmeyer SJ (2005). Cyclophilin D is a component of mitochondrial permeability transition and mediates neuronal cell death after focal cerebral ischemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 102, 12005–12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid FX (1993). Prolyl isomerase: enzymatic catalysis of slow protein-folding reactions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct 22, 123–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard CW, Finelli L, and Alter MJ (2005). Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect. Dis 5, 558–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solbak SM, Reksten TR, Wray V, Bruns K, Horvli O, Raae AJ, Henklein P, Henklein P, Roder R, Mitzner D, Schubert U, and Fossen T (2010). The intriguing cyclophilin A-HIV-1 Vpr interaction: prolyl cis/trans isomerisation catalysis and specific binding. BMC Struct. Biol 10, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano V, Madejon A, Vispo E, Labarga P, Garcia-Samaniego J, Martin-Carbonero L, Sheldon J, Bottecchia M, Tuma P, and Barreiro P (2008). Emerging drugs for hepatitis C. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 13, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starzl TE, Klintmalm GB, Porter KA, Iwatsuki S, and Schroter GP (1981). Liver transplantation with use of cyclosporin a and prednisone. N. Engl. J. Med 305, 266–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strebel K, Luban J, and Jeang KT (2009). Human cellular restriction factors that target HIV-1 replication. BMC Med 7, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Hayano T, and Suzuki M (1989). Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase is the cyclosporin A-binding protein cyclophilin. Nature 337, 473–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thali M, Bukovsky A, Kondo E, Rosenwirth B, Walsh CT, Sodroski J, and Gottlinger HG (1994). Functional association of cyclophilin A with HIV-1 virions. Nature 372, 363–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Zhao C, Zhu H, She W, Zhang J, Liu J, Li L, Zheng S, Wen YM, and Xie Y (2010). Hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen interacts with and promotes cyclophilin a secretion: possible link to pathogenesis of HBV infection. J. Virol 84, 3373–3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdegem D, Badillo A, Wieruszeski JM, Landrieu I, Leroy A, Bartenschlager R, Penin F, Lippens G, and Hanoulle X (2011). Domain 3 of NS5A protein from the hepatitis C virus has intrinsic alpha-helical propensity and is a substrate of cyclophilin A. J. Biol. Chem 286, 20441–20454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, and Heitman J (2005). The cyclophilins. Genome Biol 6, 226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Liu X, Zhao Z, Xu C, Zhang K, Chen C, Sun L, Gao GF, Ye X, and Liu W (2011). Cyclophilin E functions as a negative regulator to influenza virus replication by impairing the formation of the viral ribonucleoprotein complex. PloS One 6, e22625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe A, Yoneda M, Ikeda F, Terao-Muto Y, Sato H, and Kai C (2010). CD147/EMMPRIN acts as a functional entry receptor for measles virus on epithelial cells. J. Virol 84, 4183–4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watashi K, Hijikata M, Hosaka M, Yamaji M, and Shimotohno K (2003). Cyclosporin A suppresses replication of hepatitis C virus genome in cultured hepatocytes. Hepatology 38, 1282–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watashi K, Ishii N, Hijikata M, Inoue D, Murata T, Miyanari Y, and Shimotohno K (2005). Cyclophilin B is a functional regulator of hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase. Mol. Cell 19, 111–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia WL, Shen Y, and Zheng SS (2005). Inhibitory effect of cyclosporine A on hepatitis B virus replication in vitro and its possible mechanisms. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int 4, 18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Robotham JM, Grise H, Frausto S, Madan V, Zayas M, Bartenschlager R, Robinson M, Greenstein AE, Nag A, Logan TM, Bienkiewicz E, and Tang H (2010). A major determinant of cyclophilin dependence and cyclosporine susceptibility of hepatitis C virus identified by a genetic approach. PLoS Pathog 6, e1001118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Robotham JM, Nelson HB, Irsigler A, Kenworthy R, and Tang H (2008). Cyclophilin A is an essential cofactor for hepatitis C virus infection and the principal mediator of cyclosporine resistance in vitro. J. Virol 82, 5269–5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylinen LM, Schaller T, Price A, Fletcher AJ, Noursadeghi M, James LC, and Towers GJ (2009). Cyclophilin A levels dictate infection efficiency of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid escape mutants A92E and G94D. J. Virol 83, 2044–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zander K, Sherman MP, Tessmer U, Bruns K, Wray V, Prechtel AT, Schubert E, Henklein P, Luban J, Neidleman J, Greene WC, and Schubert U (2003). Cyclophilin A interacts with HIV-1 Vpr and is required for its functional expression. J. Biol. Chem 278, 43202–43213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]