Abstract

Multi-electron redox reactions often require multi-cofactor metalloenzymes to facilitate coupled electron and proton movement, but it is challenging to design artificial enzymes to catalyze these important reactions due to their structural and functional complexity. We report a designed heteronuclear heme-[4Fe-4S] cofactor in cytochrome c peroxidase as a structural and functional model of the enzyme sulfite reductase. The initial model exhibits spectroscopic and ligand-binding properties of the native enzyme, and sulfite reduction activity was improved to be close to a native enzyme through rational tuning of the secondary sphere interactions around the [4Fe-4S] and the substrate-binding sites. By offering insight into the requirements for a demanding 6e-/7H+ reaction that has so far eluded synthetic catalysts, this study provides strategies for designing highly functional multi-cofactor artificial enzymes.

One Sentence Summary:

A heteronuclear metal cofactor in a custom-picked protein scaffold can reduce sulfite through multiple electron and proton transfer steps.

Main Text

The presence of sulfite in the environment inhibits bioremediation of pervasive, toxic oxyanions such as (per)chlorate, arsenate, and nitrate (1) that are chemically challenging to reduce and have low binding affinity to transition metals. Bio-inspired artificial catalysts have been developed to reduce nitrate and perchlorate (2), but sulfite reduction remains inaccessible to synthetic catalysts. As a result, complete oxyanion remediation has so far only been accomplished through biofilms undergoing anaerobic respiration (3, 4).

| (1) |

Sulfite reduction to sulfide (Eq. 1) is accomplished to completion by assimilatory sulfite reductase (SiR), which contains a structurally complex cofactor composed of a heme macrocycle (siroheme) and a cubane [4Fe-4S] cluster (5) bridged by a cysteine residue that serves as both the proximal ligand to the siroheme and a ligand to one Fe atom of the [4Fe-4S] cluster (Fig. 1). The [4Fe-4S] cluster is proposed to act as a “molecular battery” that facilitates electron transfer to the heme, enabling sequential 2e- reduction (6), though the precise role it plays in catalysis and tuning siroheme reactivity is not understood. Two synthetic models of the heme-[4Fe-4S] cofactor have been reported, but lacked activity (7,8). These models did not include elements of the SiR substrate binding pocket, which is rich in positively charged residues thought to facilitate binding and protonation of the substrate concurrent with electron transfer and proposed to be required for activity (9, 10). Designing artificial enzymes that include mononuclear or homonuclear metal-binding sites has been successful in generating catalysts (11–17); though, rarely have designed enzymes recapitulated the complex heteronuclear metal centers responsible for multi-electron, multi-proton reactions. Here, we report success in replicating both structural and functional elements of SiR by designing a [4Fe-4S] cluster proximal to the heme center in cytochrome c peroxidase (CcP). By rationally building secondary sphere interactions in the metal- and substrate-binding sites, we increased the sulfite reductase activity of this artificial metalloenzyme to approach the activity of a native SiR.

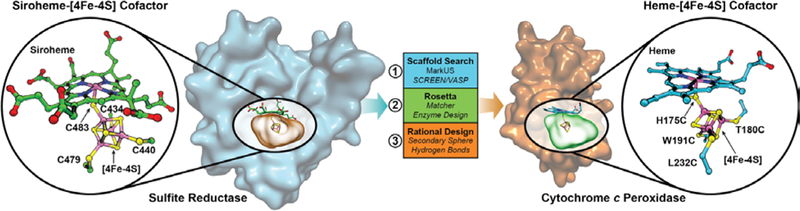

Fig. 1.

Design of a [4Fe-4S] binding site in CcP to mimic the heme-[4Fe-4S] center in native SiR. From left to right: a search structure generated from the binding cavity of the [4Fe-4S] in the siroheme-[4Fe-4S] cofactor from the hemoprotein subunit of native E. coli SiR (PDB ID 2GEP) (9) was used to search the PDB for suitable hemoprotein scaffolds. Yeast CcP was identified as a suitable scaffold, and a binding site for a heme-[4Fe-4S] cofactor as designed by a combination of computational and rational design methods. The resulting computational model of the designed heme-[4Fe-4S] center in SiRCcP.1 is shown on the right, indicating the 3 Fe-coordinating Cys mutations and the H175C mutation to create a bridging Cys between the heme and [4Fe-4S] cofactors.

We chose CcP, a native heme-binding protein, as a protein scaffolddue to its small size and stability. Further, we found that its active site contains a cavity on the heme proximal face large enough to host a [4Fe-4S] cluster (Figs. S1, S2). This heme proximal cavity was essential in discriminating amongst suitable hemoproteinscaffolds, described in the Supplementary Material (Fig. S3). We then used the Rosetta matcher and enzyme design algorithms (11) to select residues to mutate to Cys to coordinate the [4Fe-4S], resulting in mutation of four residues to Cys (H175C, T180C, W191C, and L232C) (Fig. 1) and two additional mutations for stability: M230A, made to relieve steric clash, and D235V, made to remove the nearby negative charge previously reported to interfere with Cys-heme coordination (18) (Fig. S4). The computational model of this sextuple mutant CcP (called SiRCcP.1) is a close structural match for the cofactor-binding site in native SiR (Fig. S5E) and was readily expressed in the cofactor-free apo-form (Figs. S6, S7).

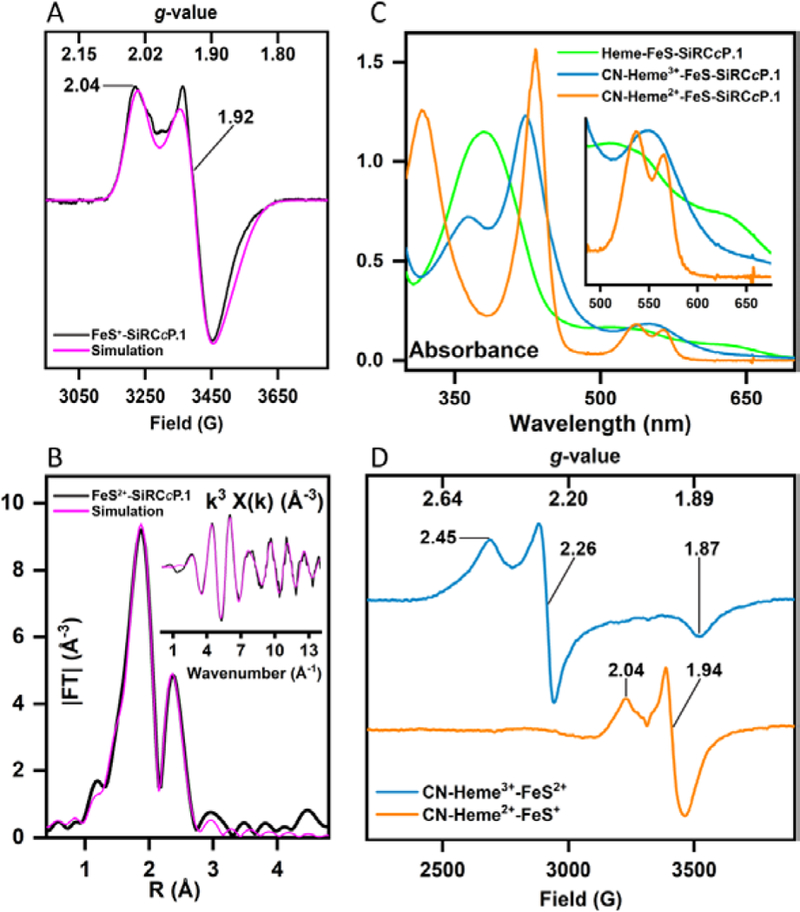

We incorporated an iron-sulfur cluster into apo-SiRCcP by in vitro reconstitution, and we refer to this protein as FeS-SiRCcP.1. We characterized FeS-SiRCcP.1 by UV-visible absorption, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), and extended fine structure x-ray absorption (EXAFS) spectroscopies, and these characterization methods of both the oxidized and reduced states indicate proper incorporation of a [4Fe-4S] cluster as designed (19, 20) (Fig. 2A,B; Figs. S8–S11). Elemental analysis for Fe to S in FeS-SiRCcP.1 matched well with the Fe and S content expected at full [4Fe-4S] incorporation (4Fe: 14S, accounting for inorganic S and all S atoms in Cys and Met residues) with a ratio of 4.00Fe:14.01S observed experimentally.

Figure 2.

Spectroscopic properties of SiRCcP. 1 with [4Fe-4S], heme, and heme-[4Fe-4S] cofactors confirm binding of [4Fe-4S] and heme-[4Fe-4S] cofactors. (A) X-band EPR spectrum of FeS-SiRCcP.1 reduced with an excess of sodium dithionite (black) and simulated spectrum (magenta) indicating an S = ½ species consistent with a [4Fe-4S]+: gx = 1.891, gy = 1.919, gz = 2.035; linewidths (G) Ax=42, Ay=27, Az=25 The spectrum shown was measured at a frequency of 9.173 GHz and modulation amplitude of 10 Gauss; microwave power = 10 mW, and a temperature of 15 K. No paramagnetic species at g = 2 are observed before reduction, suggesting a [4Fe-4S]2+ (S = 0) state as-prepared (oxidized). A [3Fe-4S]+ species could be generated by re-oxidation of the reduced species with an excess of potassium ferricyanide (Fig. S10). (B) Magnitude of the phase-uncorrected k3-weighted Fourier transform and EXAFS (inset) of the Fe K-edge spectra for FeS2+-SiRCcP. 1 (black) and best-fit (magenta). The EXAFS spectrum is consistent with a symmetrical cubane structure (three scattering Fe atoms per absorber Fe and four scattering S atoms in the first coordination shell). Fitting parameters are given in Table S1 and the EXAFS of FeS+-SiRCcP.1 are plotted in Fig. S11. (C) UV-visible spectra of Fe-S reconstituted SiRCcP.1 (FeS-SiRCcP.1) and heme-Fe-S reconstituted SiRCcP.1 (Heme-FeS-SiRCcP. 1) in the presence and absence of potassium cyanide. FeS-SiRCcP. 1 as-prepared has weak, broad absorption at 400 nm which decreases upon reduction (Fig. S9). Ferric Heme-FeS-SiRCcP. 1 has a blue-shifted Soret (378 nm) relative to native CcP (408 nm) and exhibits a Soret maximum and Q-bands (inset) consistent with penta-coordinate, thiolate-ligated high-spin ferriheme. The ferrous Heme-FeS-SiRCcP.1 spectrum obtained by incubation with sodium dithionite (Fig. S12) is distinct from the species obtained by photoreduction (Fig. S13) and is identical to the spectrum of Heme2+-FeS+-SiRCcP. 1 incubated with sulfite under non-turnover conditions (Fig. S14), indicating sulfite-bound hexacoordinate ferroheme. The photoreduced spectrum (Fig. S13) represents the ferrous pentacoordinate species. (D) X-band EPR spectra of Heme-FeS-SiRCcP.1 in the presence of cyanide. CN-Heme3+-FeS2+-SiRCcP.1 is predominantly low-spin ferric heme (gx = 1.87, gy = 2.26, gz = 2.45) with no visible [4Fe-4S] features. In the all ferrous state, heme features disappear (presumably S = 0 ferrous heme) while the S = ½ [4Fe-4S] feature reappears. Similar behavior has been reported for CN-bound SiRHP. EPR spectra were measured at 18 K with a microwave power of 10 mW at a frequency of 9.24 GHz.

In addition to the [4Fe-4S], a heme cofactor is required to complete the SiR catalyst, and we found that heme-b, the native heme cofactor of CcP, could be incorporated into FeS-SiRCcP. 1 in vitro, similarly to native CcP. We call this double-cofactor form Heme-FeS-SiRCcP.1 (Fig. 2C). Elemental analysis of Heme-FeS-SiRCcP.1 yielded 5.54 Fe per heme, confirming that the [4Fe-4S] remains intact following heme reconstitution. Heme-FeS-SiRCcP.1 displayed key spectroscopic features and ligand binding properties of thiol-ligated hemoproteins and even native SiR (Fig. 2C,D; Figs. S12–S14) (21–23). Notably, Heme3+-FeS2+-SiRCcP.1 has low affinity for cyanide anion (CN-), requiring ~2000 equivalents, whereas 1e- reduced Heme2+-FeS2+-SiRCcP rapidly binds ~1 equivalent of CN- (Fig. 2C). This behavior has been reported for SiR (24) but not most other hemoproteins, including CcP, suggesting that our designed SiRCcP.1 substantially alters the heme character of the native scaffold protein without altering heme chemical structure. The presence of the positively charged [4Fe-4S] could screen the increased negative charge in ferrous heme that tends to weaken the CN—Fe2+ interaction in hemoproteins, but we also observed higher CN- affinity in Heme2+-SiRCcP.1 with no reconstituted [4Fe-4S]. Therefore, local electrostatic effects, perhaps related to removal of the proximal His-Asp-Trp peroxidase triad in SiRCcP.1 (Fig. S2), or changes in heme conformation that impact σ acceptance and π back-donation must also play a role (25–27).

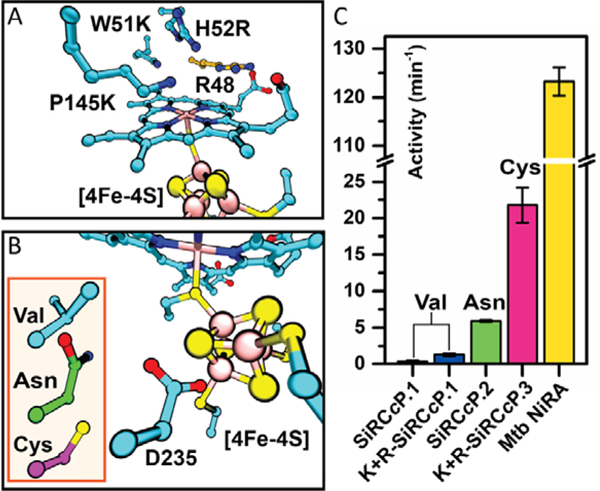

We measured the sulfite reductase activity of Heme-FeS-SiRCcP.1 by the rate of oxidation of the electron mediator methyl viologen (MV+) in the presence of sodium sulfite using a protocol previously reported for native SiR (28). Heme-FeS-SiRCcP.1 oxidizes MV+ at a rate of 0.348(±0.15) min−1, whereas WTCcP displayed no measurable activity above background. Similarly, the rate by Heme-FeS-SiRCcP.1 was nominally zero in the absence of sulfite. The initial design that incorporated the heme-[4Fe-4S] cofactor (SiRCcP.1), therefore, showed notable sulfite reduction activity over its native scaffold protein but far less than a native SiR, indicating that a heme-[4Fe-4S] cofactor alone is insufficient to promote rapid sulfite reduction. To improve activity, we sought to systematically examine the key features of native SiR active sites and determine which had the greatest impact on catalysis. Lys and Arg residues are conserved in SiR and are thought to be important for substrate binding and catalysis (9, 10) (Fig. S15A). Therefore, we introduced analogous W51K, H52R, and P145K mutations to SiRCcP.1, which when combined with the native CcP residue Arg48, form a positively charged cavity that resembles SiR (Fig. 3A, S15B). The reductase activity of the resulting mutant, W51K/H52R/P145K-SiRCcP.1, is (1.26±0.20 min−1), 5.3-fold greater than SiRCcP.1.

Fig. 3.

Sulfite reduction activity of SiRCcP mutants is modulated by substrate binding and [4Fe-4S] secondary sphere mutations. (A) Computational model of the SiRCcP substrate-binding site with mutations W51K, H52R, and P145K (cyan) made to mimic native SiR residues K217, R153, and K215, respectively (Fig. S15). The native CcP residue R48 (orange) is positioned similarly to R83 in native SiR. (B) Computational model of the mutations D235V (SiRCcP.1, cyan), D235N (SiRCcP.2, green), and D235C (SiRCcP.3, magenta) in SiRCcP. (C) Sulfite reduction activity of four SiRCcP mutants in comparison to a native sulfite reductase from M. tuberculosis (Mtb NiRA). “K+R” denotes the presence of the three mutations W51K/H52R/P145K. Reported activities represent the average of triplicate measurements with standard error (see Table S2).

[4Fe-4S] clusters are stabilized in proteins by backbone and amino acid sidechain interactions in the secondary coordination sphere (29, 30). The crystal structures of SiRs reveal several sidechain hydrogen bond donors to inorganic S atoms, such as the amino group of N481 in SiRHP (Fig. S16A). We sought to increase the activity of SiRCcP by adding similar stabilizing interactions to the [4Fe-4S] cluster secondary coordination sphere by mutating residue D235, whose functional group is oriented toward the [4Fe-4S] in SiRCcP in a position similar to N481 in SiRHP, to Asn and Cys based on important secondary sphere residues in various [4Fe-4S] centers (29). We found that the D235N mutation (called SiRCcP.2, Fig. 3B, S16B) increased activity to 5.91±1.6 min−1, 4.3-fold greater than W51K/H52R/P145K-SiRCcP.1 (a 17-fold increase over SiRCcP.1). We achieved an even greater increase in activity with the D235C mutant (called SiRCcP.3, Fig. 3B), which when combined with the substrate binding site mutations given above (W51K/H52R/P145K-SiRCcP.3) exhibited sulfite reduction activity of 21.8(±2.4) min−1, a 63-fold increase over SiRCcP.1 (Fig. S17, Table S2). We compared these rates to a native dissimilatory SiR, NiRA from M. tuberculosis (Mtb NiRA) (28), whose activity has been reported under comparable reaction conditions, and found that the activity of W51K/H52R/P145K-SiRCcP.3 is ca. 18% of a native SiR (Fig. 3C and Table S2). Assimilatory SiR have been observed to reduce of sulfite to sulfide with minimal side products, but dissimilatory SiR typically achieve far less than 50% efficiency in vitro. We quantified sulfide as well as the side products trithionate (S3O62-) and thiosulfate (S2O32-) produced with sulfite as the substrate. Sulfide was quantified by methylene blue formation, and we found that ca. 10% of the products formed in the reaction were hydrogen sulfide (the 6-electron reduction product), with the remainder being primarily the 2- and 4-electron reduced side-products in a distribution similar to native dissimilatory SiR. Together, these products account for greater than 90% of the electron donors consumed (Fig. S18–S19). The product conversion efficiency of W51K/H52R/P145K-SiRCcP.3 is therefore similar to the efficiency of a natural dissimilatory SiR (31). SiRCcP is thus both a close structural model and a substantially active functional model of SiR capable of complete 6e- and 7H+ sulfite reduction.

Our progressive optimization of SiRCcP revealed structural features beyond the metallocofactor required for efficient multi-electron reduction of an oxyanion, including secondary sphere interactions such as hydrogen bonding to the [4Fe-4S] (through D235V/N/C mutations) and residues that may promote substrate binding and protonation (through W51K, H52R, and P145K mutations). Models that did not incorporate these features had diminished activity, and the necessity of these secondary interactions in our SiRCcP model has important implications for optimizing design strategies to achieve high activity in multi-electron redox reactions with artificial enzymes, a process simplified and accelerated in this study by cavity-based scaffold selection. Furthermore, the SiRCcP enzyme is functional with the heme-b cofactor present in native CcP instead of the biologically unique siroheme in SiR, suggesting that siroheme is not absolutely required for sulfite reduction. These insights, combined with the ability to recapitulate a complex multi-electron/proton delivery system in a simple, stable scaffold suggest a strategy to design highly active catalysts for other difficult oxyanion reduction and multi-electron reactions that are important to society.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We wish to thank Dr. Robert Schnell from Karolinska Institutet Stockholm (Sweden) for providing plasmids used to express the native SiR from M. tuberculosis (Mtb NiRA) and Professors Thomas B. Rauchfuss and Alison R. Fout for helpful discussions. We thank Yongjae Lee for his help in collecting some enzyme activity data. X-ray absorption studies were conducted at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, and we wish to thank beamline scientists Matthew Latimer and Erik Nelson for their indispensable help. All work reported in this communication was conducted at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. I.D.P. is currently affiliated with Ambry Genetics, Bioinformatics Department, Aliso Viejo, CA; P. H. is currently affiliated with Department of Biochemistry and Institute for Protein Design, University of Washington; Y.L. is also affiliated with Department of Bioengineering, Materials Science and Engineering, and Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology.

Funding: The work described in this paper is supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01-GM062211 to Y.L. and a predoctoral training grant 5T32-GM827625 to E.N.M.); Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02–76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH.

Footnotes

Competing interests: E.N.M., P.H., and Y.L. are inventors on patent application 62/702,940 submitted by University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign that covers Artificial Metalloproteins as Biocatalysts for Sulfite Reduction.

Data and materials availability: All data are available in the main text or supplementary materials. All SiRCcP variants described in this report (SiRCcP.1, SiRCcP.2, and SiRCcP.3 and their W51K/H52R/P145K variants as described in the main text) are available from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign under a material transfer agreement with the University.

References and Notes:

- 1.Townsend GT, Suflita JM, Influence of sulfur oxyanions on reductive dehalogenation activities in Desulfomonile tiedjei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 3594–3599 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford CL, Park YJ, Matson EM, Gordon Z, Fout AR, A bioinspired iron catalyst for nitrate and perchlorate reduction. Science. 354, 741–743 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung J, Rittmann BE, Wright WF, Bowman RH, Simultaneous Bio-reduction of Nitrate, Perchlorate, Selenate, Chromate, Arsenate, and Dibromochloropropane Using a Hydrogen-based Membrane Biofilm Reactor. Biodegradation. 18, 199 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stolz JF, Oremland RS, Bacterial respiration of arsenic and selenium. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 23, 615–627 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crane BR, Siegel LM, Getzoff ED, Sulfite reductase structure at 1.6 Angstrom: evolution and catalysis for reduction of inorganic anions. Science. 270, 59 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Surducan M, Makarov SV, Silaghi-Dumitrescu R, O-S Bond Activation in Structures Isoelectronic with Ferric Peroxide Species Known in O-O-Activating Enzymes: Relevance for Sulfide Activation and Sulfite Reductases: O-S Bond Activation in Ferric-Peroxide-Type Species. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 5827–5837 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai L, Holm RH, Synthesis and Electron Delocalization of [Fe4S4]-S-Fe (III) Bridged Assemblies Related to the Exchange-Coupled Catalytic Site of Sulfite Reductases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 7177–7188 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou C, Cai L, Holm RH, Synthesis of a [Fe4S4]-S-ferriheme bridged assembly containing an isobacteriochlorin component: A further analogue of the active site of sulfite reductase. Inorg. Chem. 35, 2767–2772 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crane BR, Siegel LM, Getzoff ED, Probing the Catalytic Mechanism of Sulfite Reductase by X-ray Crystallography: Structures of the Escherichia coli Hemoprotein in Complex with Substrates, Inhibitors, Intermediates, and Products,. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 36, 12120–12137 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith KW, Stroupe ME, Mutational Analysis of Sulfite Reductase Hemoprotein Reveals the Mechanism for Coordinated Electron and Proton Transfer. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 51, 9857–9868 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel JB et al. , Computational Design of an Enzyme Catalyst for a Stereoselective Bimolecular Diels-Alder Reaction. Science. 329, 309–313 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyster TK, Knorr L, Ward TR, Rovis T, Biotinylated Rh(III) Complexes in Engineered Streptavidin for Accelerated Asymmetric C-H Activation. Science. 338, 500–503 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zastrow ML, Peacock AFA, Stuckey JA, Pecoraro VL, Hydrolytic catalysis and structural stabilization in a designed metalloprotein. Nat. Chem. 4, 118–123 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrik ID, Liu J, Lu Y, Metalloenzyme design and engineering through strategic modifications of native protein scaffolds. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 19, 67–75 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu Y et al. , A Designed Metalloenzyme Achieving the Catalytic Rate of a Native Enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 11570–11573 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polizzi NF et al. , De novo design of a hyperstable non-natural protein–ligand complex with sub-Å accuracy. Nat. Chem. 9, 1157–1164 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwizer F et al. , Artificial Metalloenzymes: Reaction Scope and Optimization Strategies. Chem. Rev. 118, 142–231 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sigman JA, Pond AE, Dawson JH, Lu Y, Engineering Cytochrome c Peroxidase into Cytochrome P450: A Proximal Effect on Heme–Thiolate Ligation. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 38, 11122–11129 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson DC, Dean DR, Smith AD, Johnson MK, Structure, Function, and Formation of Biological Iron-Sulfur Clusters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 247–281 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulholland SE, Gibney BR, Rabanal F, Dutton PL, Characterization of the Fundamental Protein Ligand Requirements of [4Fe-4S]2+/+ Clusters with Sixteen Amino Acid Maquettes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 10296–10302 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janick PA, Siegel LM , Electron paramagnetic resonance and optical spectroscopic evidence for interaction between siroheme and iron sulfide (Fe4S4) prosthetic groups in Escherichia coli sulfite reductase hemoprotein subunit. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 21, 3538–3547 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luthra A, Denisov IG, Sligar SG, Spectroscopic features of cytochrome P450 reaction intermediates. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 507, 26–35 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janick PA, Siegel LM, Electron paramagnetic resonance and optical evidence for interaction between siroheme and the tetranuclear iron-sulfur center (Fe4S4) prosthetic groups in complexes of Escherichia coli sulfite reductase hemoprotein with added ligands. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 22, 504–515 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krueger RJ, Siegel LM, Evidence for siroheme-iron sulfide (Fe4S4) interaction in spinach ferredoxin-sulfite reductase. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 21, 2905–2909 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boffi A, Ilari A, Spagnuolo C, Chiancone E, Unusual Affinity of Cyanide for Ferrous and Ferric Scapharca inaequivalvis Homodimeric Hemoglobin. Equilibria and Kinetics of the Reaction †. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 35, 8068–8074 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddy KS et al. , Infrared Spectroscopy of the Cyanide Complex of Iron(II) Myoglobin and Comparison with Complexes of Microperoxidase and Hemoglobin †. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 35, 5562–5570 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Noll BC, Schulz CE, Scheidt WR, Comparison of Cyanide and Carbon Monoxide as Ligands in Iron(II) Porphyrinates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 5010–5013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnell R, Sandalova T, Hellman U, Lindqvist Y, Schneider G, Siroheme- and [Fe4-S4]-dependent NirA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis Is a Sulfite Reductase with a Covalent Cys-Tyr Bond in the Active Site. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 27319–27328 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck BW, Xie Q, Ichiye T, Sequence Determination of Reduction Potentials by Cysteinyl Hydrogen Bonds and Peptide Dipoles in [4Fe-4S] Ferredoxins. Biophys. J. 81, 601–613 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dey A et al. , Solvent Tuning of Electrochemical Potentials in the Active Sites of HiPIP Versus Ferredoxin. Science. 318, 1464–1468 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crane BR, Getzoff ED, The relationship between structure and function for the sulfite reductases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6, 744–756 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer M et al. , MarkUs: a server to navigate sequence–structure–function space. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W357–W361 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nayal M, Honig B, On the nature of cavities on protein surfaces: Application to the identification of drug-binding sites. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 63, 892–906 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen BY, Honig B, VASP: A Volumetric Analysis of Surface Properties Yields Insights into Protein-Ligand Binding Specificity. PLOS Comput. Biol. 6, e1000881 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finzel BC, Poulos TL, Kraut J, Crystal structure of yeast cytochrome c peroxidase refined at 1.7-A resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 13027–13036 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodin DB, McRee DE, The Asp-His-Fe triad of cytochrome c peroxidase controls the reduction potential, electronic structure, and coupling of the tryptophan free radical to the heme. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 32, 3313–3324 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bravo J et al. , Crystal structure of catalase HPII from Escherichia coli. Structure. 3, 491–502 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertrand T et al. , Crystal Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Catalase-Peroxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38991–38999 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang CH, Kim K, Density Functional Theory Calculation of Bonding and Charge Parameters for Molecular Dynamics Studies on [FeFe] Hydrogenases. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 5, 1137–1145 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips JC et al. , Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin D, MacKerell AD, Combined ab initio/empirical approach for optimization of Lennard–Jones parameters. J. Comput. Chem. 19, 334–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K, VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 33–38 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pfister TD et al. , Kinetic and crystallographic studies of a redesigned manganese-binding site in cytochrome c peroxidase. JBIC J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 12, 126 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barr I, Guo F, Pyridine Hemochromagen Assay for Determining the Concentration of Heme in Purified Protein Solutions . Bio-Protoc. 5 (2015) (available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4932910/). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yonetani T, Anni H, Yeast cytochrome c peroxidase. Coordination and spin states of heme prosthetic group. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 9547–9554 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kent TA, Huynh BH, Münck E, Iron-sulfur proteins: spin-coupling model for three-iron clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 77, 6574–6576 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beinert H et al. , Iron-sulfur stoichiometry and structure of iron-sulfur clusters in three-iron proteins: evidence for [3Fe-4S] clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 80, 393–396 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papaefthymiou V, Girerd JJ, Moura I, Moura JJG, Muenck E, Moessbauer study of D.gigas ferredoxin II and spin-coupling model for Fe3S4 cluster with valence delocalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109, 4703–4710 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beinert H, Holm RH, Münck E, Iron-Sulfur Clusters: Nature’s Modular, Multipurpose Structures. Science. 277, 653–659 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agarwalla S, Stroud RM, Gaffney BJ, Redox Reactions of the Iron-Sulfur Cluster in a Ribosomal RNA Methyltransferase, RumA. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34123–34129 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoppe A, Pandelia M-E, Gärtner W, Lubitz W, [Fe4S4]- and [Fe3S4]-cluster formation in synthetic peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Bioenerg. 1807, 1414–1422 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ravel B, Newville M, ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fogo JK, Popowsky M, Spectrophotometric Determination of Hydrogen Sulfide. Anal. Chem. 21, 732–734 (1949). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen J-S, Mortenson LE, Inhibition of methylene blue formation during determination of the acid-labile sulfide of iron-sulfur protein samples containing dithionite. Anal. Biochem. 79, 157–165 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hallenbeck PC, Clark MA, Barrett EL, Characterization of anaerobic sulfite reduction by Salmonella typhimurium and purification of the anaerobically induced sulfite reductase. J. Bacteriol. 171, 3008–3015 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kelly DP, Chambers LA, Trudinger PA, Cyanolysis and spectrophotometric estimation of trithionate in mixture with thiosulfate and tetrathionate. Anal. Chem. 41, 898–901 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hatchikian EC, Zeikus JG, Characterization of a New Type of Dissimilatory Sulfite Reductase Present in Thermodesulfobacterium commune. J. Bacteriol. 153, 1211–1220 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan J, Cowan JA, Enzymic redox chemistry: a proposed reaction pathway for the six-electron reduction of sulfite to sulfide by the assimilatory-type sulfite reductase from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough). Biochemistry (Mosc.). 30, 8910–8917 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.