Abstract

Aim

To describe published literature on the needs and experiences of family members of adults admitted to intensive care and interventions to improve family satisfaction and psychological well‐being and health.

Design

Scoping review.

Methods

Several selective databases were searched. English‐language articles were retrieved, and data extracted on study design, sample size, sample characteristics and outcomes measured.

Results

From 469 references, 43 studies were identified for inclusion. Four key themes were identified: (a) Different perspectives on meeting family needs; (b) Family satisfaction with care in intensive care; (c) Factors having an impact on family health and well‐being and their capacity to cope; and (d) Psychosocial interventions. Unmet informational and assurance needs have an impact on family satisfaction and mental health. Structured written and oral information shows some effect in improving satisfaction and reducing psychological burden. Future research might include family in the design of interventions, provide details of the implementation process and have clearly identified outcomes.

Keywords: anxiety and uncertainty, Family, intensive care, interventions, needs, satisfaction

1. INTRODUCTION

In the UK, 191,016 patients were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) in 2016. This figure rose to 193,813 in 2017 (Scottish Intensive Care Society Audit Group, (SIGSAG) (2017, 2018), Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre, (ICNARC) 2017). With increases in the number of patient admissions to ICU come increases in poorer patient outcomes, for example, 20% of patients die prior to the hospital discharge or undergo a prolonged period of recovery (SIGSAG & ICNARC, 2017, 2017).

Admission to the ICU is often, although not always, unexpected, and the patient's condition is usually unstable (Delva, Vanoost, Bijttebeir, Lauwers, & Wilmer, 2002). Many ICU patients are unable to communicate with healthcare staff or participate in decision‐making about their treatment due to the severity of their illness, delirium or sedation (Mitchell, Burmeister, & E & Foster M, 2009). Consequently, healthcare professionals are increasingly approaching family members to speak for them and expanding the care and support provided from the patient to their family as well (Al‐Mustair, Plummer, O'Brien, & Clerehan, 2013). Involving the patient's family in the ICU stage of care is essential to enable healthcare providers to fully deliver person‐centred care. Often family members who know the patient best are not considered as part of the care team (Paul & Finney, 2015).

Admission to ICU, whether planned or unplanned, however means that family members may suddenly be faced with decision‐making and uncertainty about their relatives’ acute condition and prognosis (Paul & Rattray, 2008). Research suggests they are frequently overwhelmed by feelings of anxiety and worry due to fear of losing their loved one, deterioration of the family structure, concerns about the future, coupled with the stressful technological ICU environment (Bijttebeir, Vanoost, Delva, Ferdinande, & Frans, 2001; Delva et al., 2002). Up to 50% of relatives experience emotional distress or anxiety for up to two years after hospital discharge which influences their quality of life and lifestyle (Paul & Rattray, 2008). For these reasons, ICU care and quality measurement should include the families’ perspective of whether their needs were met or not, satisfaction with the care process and outcome and evaluation of interventions to improve their psychological health and well‐being (Flaatten, 2012). Current literature primarily focuses on healthcare professionals’ knowledge and understanding of family needs. It provides little insight from the perspective of the family as to what their experiences are, how they perceive the care delivered and the impact of having a loved one in ICU. There is limited research describing family experiences whilst in ICU and structured interventions that might support them during the patient's critical illness. The aim of this scoping review is to describe published literature on the needs and experiences of family members of adults admitted to intensive care and interventions to improve family satisfaction and psychological well‐being and health.

2. METHOD

The method adopted for this review was informed by Arskey and O'Malley (2005) scoping review framework. Scoping reviews are undertaken to examine the extent and nature of research activity in a particular field, to summarize and disseminate research findings and identify gaps in the literature (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). The suggested steps in a scoping review are to: (a) identify the research questions; (b) identify relevant studies; (c) study selection; (d) chart the data; and (e) collate, summarize and report the results (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). Scoping reviews do not address issues of quality appraisal but rather they have the potential to produce a large number of studies with different study designs and methodologies.

2.1. Research questions

The research questions posed before the literature search started were as follows:

What is currently known about family needs and family satisfaction with care?

What were the psychological symptoms experienced by family members in the ICU and the interventions available aimed at reducing those symptoms?

2.2. Identifying relevant studies and study selection

The search strategy involved searching the following electronic databases: Medline, Cinahl, Embase, Psycho Info, Science Direct and Cochrane library of systematic reviews and Google scholar. The search terms used included the following: family, intensive care, satisfaction, needs, interventions, anxiety and uncertainty. The search covered the period 1979–2017 as the first seminal study in this area was published in 1979. To be included in this review, published studies or prior literature reviews had to include relatives of adult critically ill patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Only published papers published or translated into English were included.

2.3. Charting the data

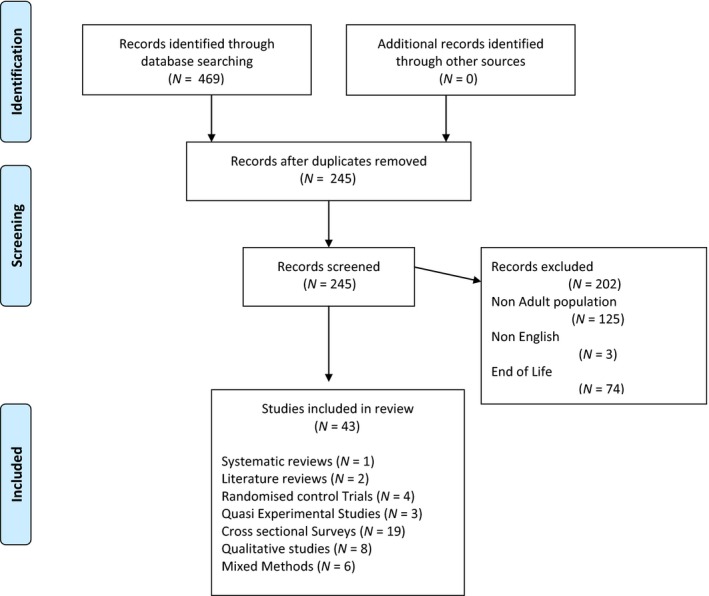

The article selection process is summarized in Figure 1. Consistent with the approach proposed by Arksey and O'Malley, (2005), the findings from each paper selected were organized and key themes developed pertinent to the scoping aim.

Figure 1.

Article selection process for scoping review

A full list of articles were obtained and screened for duplicates by the lead author. Abstracts were examined to identify publications that met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review and reviewed by lead author. Reference lists of relevant articles and eligible primary research studies or reviews were checked by hand to identify articles not captured by electronic searches.

2.4. Collating, summarizing and reporting results

To enable a logical and descriptive summary of the results, data were extracted using the following key headings: authors(s), year of publication and title of publication; country of origin; study design; sample size; sample characteristics; intervention type and outcome.

2.5. Ethics

Research Ethics Committee approval was deemed not required as this was a scoping review.

3. RESULTS

In total, 468 published papers were retrieved. Removing duplicates and screening abstracts and full texts resulted in the inclusion of 43 published articles which included 40 research studies, one systematic review and two literature review (Figure 1). The quantitative research studies included four randomized control trials, three quasi‐experimental studies and 19 cross‐sectional surveys. The qualitative research included two grounded theory studies and six other studies that employed a qualitative approach although no specific design was specified. A further six studies used a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches. The papers retrieved were published in journals aimed at the medical profession (N = 21), followed by nursing (N = 20), psychology (N = 1) and social work (N = 1). Most of the studies were conducted in the USA (N = 13), followed by Canada (N = 4), France (N = 4), Denmark/Norway/Sweden (N = 4), Hong Kong (N = 3), Australia (N = 3), Belgium (N = 3), Jordan/Iran (N = 2), UK (N = 3), Germany (N = 1), Greece (N = 1), Turkey (N = 1) and Spain (N = 1). The settings were specified as general ICUs, which incorporated medical, surgical, neurological and trauma patients (N = 35) and neurological ICU (N = 5).

Four key themes were identified from the scoping review: (a) Different perspectives on meeting family need; (b) Family satisfaction with care in ICU (c) Factors having an impact on family well‐being and their capacity to cope; and (d) Psychosocial interventions.

3.1. Theme 1 different perspectives on meeting family need

Under Theme 1, two key areas related to meeting family needs were identified, namely family member's perceptions of their needs and the healthcare team's perceptions of family needs.

3.1.1. Family member's perception of their needs

Four quantitative studies (Auerbach et al., 2005; Lee & Lau., 2003; Molter, 1979; Omari, 2009) and three qualitative studies (Bond, Draeger, Mandleco, & Donnelly, 2003; Fry & Warren, 2007; Keenan & Joseph, 2010) were identified, and one literature review (Verhaeghe, Defloor, Zuuren, Duijnstee, & Grypdonck, 2005) explored family members’ perceptions of their needs (Table 1). All four quantitative studies used the Critical Care Family Needs Inventory (CCFNI), a 45‐item self‐report questionnaire that assessed family needs within five dimensions: support, comfort, information, proximity and assurance (Molter, 1979). Most studies were single centre. Family needs data were obtained during the acute phase of critical illness (first 24–72 hr). The most important family needs identified were for information and assurance, followed by proximity, comfort and support, respectively. A recent literature review concluded that information and assurance appeared to be the greatest universal needs of family members of critically ill patients (Al Mustair et al., 2013; Verhaeghe et al., 2005). Families want timely, clear and understandable information about their relative's medical condition, but without leaving room for unrealistic hope.

Table 1.

Studies of family needs

| Author | Aim | Setting | Sample size | Method | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auerbach et al. (2005) | To examine family members perceptions of whether their needs were met in a trauma ICU at both at admission and prior to discharge | One Trauma ICU in teaching hospital in the United States (USA) | Forty family members |

Quantitative CCFNI |

On Admission,most prominent of unmet needs were information, explanations and comfortable waiting area Discharge—tended to show all needs were being met |

| Bijttebier et al. (2001) | To investigate differences between perceptions of family members, physicians and nurses about the needs of relatives of critical care patients. | One general ICU of a University Hospital in Belgium | Two hundred family members, 38 physicians, 143 nurses | Quantitative CCFNI | Information emerged as being the most important factor across all three groups. Nurses and physicians underestimated this need. |

| Bond et al. (2003) | To describe the needs of families of patients with severe traumatic brain injury in a neurosurgical ICU | One neurological ICU in trauma centre USA | Seven family members | Qualitative‐Exploratory interviews |

Content analysis of the interviews identified 4 themes The need to know, The need for consistent information, The need for involvement The need to make sense of the experience |

| Fry and Warren (2007) | To describe the perceived needs of the ICU family members viewed from their own words | One General ICU in the USA | Fifteen family members | Qualitative‐Contextual analysis using interviews | 4 explicit needs were expressed by all participants. These needs were seeking information. Trusting the professionals. Being a part of the care and maintaining a positive outlook. |

| Hinkle et al. (2009) | To describe family members needs of ICU patients identified by family members and nurses. | Six ICU's (4 neurological and 2 surgical) in the USA | Hundred and one family members and nurses | Qualitative‐descriptive approach |

Hierarchical cluster analysis identified the 4 themes of Emotional resources and support Trust and facilitation of needs Treatment information Feelings Family members and nurses differed significantly on three of the four themes |

| Hinkle & Fitzgerald (2011) | Needs of American relatives of intensive care patients: Perceptions of nurses, physicians and relatives | Six ICU's (4 neurological and 2 surgical) in the USA | Hundred and one family members, 28 physicians and109 nurses |

Quantitative CCFNI |

The three most important needs were 1)To have questions answered honestly 2)To be assured that the best care possible is being given to the patient 3)To feel the hospital personnel care about the patient. |

| Keenan and Joseph (2010) | Identify the needs of family members of ICU patients who have sustained a severe traumatic brain injury | One neurological ICU in Canada | Twenty‐five family members | Qualitative Semi‐structured Interviews | Key themes identified were as follows: The need to talk about their experience. To receive information about the injury and prognosis. To be supported by professionals in becoming involved in their relative's care. |

| Kinrade et al. (2010) | To investigate the needs of relatives whose family member is unexpectedly admitted to the ICU and compare them with nurses perspectives of family needs | One general ICU in Australia | Twenty‐five family members, 33 nurses | Quantitative CCFNI | The importance of the need for information provision and communication between family members and ICU staff was identified of key importance |

| Lee and Lau (2003) | To identify the immediate needs of family members in a general ICU | One general medical, surgical and neurological ICU in Hong Kong | Forty family members |

Quantitative CCFNI |

Reassurance and Proximity‐most important unmet needs |

| Leung et al. (2000) | To identify family members perceptions of immediate needs within 48–96 hr following admission of a relative to critical care | One general ICU in Hong Kong | Thirty‐seven family members, 45 registered nurses | Quantitative CCNFI | Top need for families was assurance and for nurses it was information. |

| Molter (1979) | To identify the needs of relatives of critically ill patients. | Two general ICU in the USA | Forty family members | Quantitative CCNFI |

Top three needs were as follows: Assurance, Information and proximity |

| Omari 2009 | To identified the perceived needs of family members who have a family member admitted to the ICU | Six general ICUs in 3 hospitals in Jordan: Ministry of Health, university hospital, and private hospital | Hundred and thirty‐nine family members | Quantitative CCFNI | The Assurance and Information subscales were perceived as the most important, but the needs associated with these items were met inconsistently |

| Ozbayir et al., 2014 | To compare intensive care nurses and relatives perceptions about intensive care family's needs | A general ICU in one teaching hospital in Turkey | Seventy family members, 70 registered nurses | Quantitative CCFNI | The CCFNI rankings for the two groups were similar for eight out of the ten most highly ranked items but differed in order. Families ranked assurance and information as key priorities. Nurses ranked proximity, assurance then information |

| Takman and Severinsson (2006) | To describe and explore nurses and physicians perceptions of relatives needs | Eight medical and surgical ICUs in Norway and Sweden | Ninety‐seven Registered Nurses and 5 Physicians | Quantitative and Qualitative CCFNI plus 1 open‐ended item |

Qualitative content analysis —Identified four categories: ‐The need to feel trust in the healthcare providers’ ability ‐The need for ICU and other hospital resources, ‐The need to be prepared for the consequences of critical illness and “patients” needs ‐Reactions in relation to significant others |

There was generally consistency across studies in how the importance of these needs is ranked, although some variations do occur (Auerbach et al., 2005; Lee & Lau, 2003), which were attributed to differences in patient's severity of illness, cultural expectations, differences in ICU practices and healthcare systems (Lee & Lau, 2003; Verhaeghe et al., 2005). Age, gender, relationship to the patient, length of patient stay in the ICU and patient diagnosis were not found to be correlated with family members' ranking of needs (Omari, 2009; Verhaeghe et al., 2005).

The qualitative studies of family member's perceptions of need provide a deeper understanding of family needs whilst in the ICU. All qualitative data describe that family members feel the need to create an alliance with healthcare staff and that this had a positive impact on their ability to handle the situation they are being faced with (Bond et al., 2003; Fry & Warren, 2007; Keenan & Joseph, 2010). Families who were confident and trusting in healthcare staff's ability to care for their relative felt more able to leave at night and take care of both themselves and their other family members (Fry & Warren, 2007). Those who perceived a lack of trust or engagement with healthcare staff describe difficulty in coping, lack of confidence, hesitancy to ask questions and dissatisfaction with care provided (Fry & Warren, 2007). Bond et al. (2003) described that inclusion of family members by the ICU team not only increased their understanding of the gravity of the patient's situation but helped prepare them for their potential caregivers role on discharge from hospital.

3.1.2. Healthcare teams perceptions of family needs

Few studies have evaluated the ability of healthcare staff to meet and satisfy the needs of ICU family members. Three single‐centre quantitative studies (Kinrade, Jackson, & Tomany, 2010; Leung, Chien, & Mackenzie, 2000; Ozbayir, Tasdemir, & Ozseker, 2014) and one multicentre qualitative study included only nursing staff (Hinkle, Fitzpatrick, & Oskrochi, 2009) (Table 1). Three studies, two of which were multicentre, evaluated both medical and nursing staff perspectives of family needs, two using quantitative methods (Bijttebier et al., 2001; Hinkle & Fitzgerald, 2011) and one mixed methods (Takman & Severinsson, 2006). Healthcare staff ranked the need for information and assurance as the top two important needs in all studies. Yet, despite this, both needs were the most frequently cited by family members as being unmet by healthcare staff (Hinkle et al., 2009; Leung et al., 2000; Omari, 2009). Unmet needs were reported to occur because ICU nurses and doctors do not perceive family needs accurately, undervalue their role and/or fail to sufficiently support the family (Bijttebeir et al., 2001; Hinkle et al., 2009; Leung et al., 2000). The patient's illness severity may also mean that the time available for communication with healthcare staff is limited and the ability to engage in discussion is compromised by the patient's clinical condition (Bijttebeir et al., 2001). Interestingly, age, gender, academic qualifications and working experience did not predict the healthcare providers’ ranking of needs of the family of the critically ill patient (Takman & Severinsson, 2006).

3.2. Theme 2 Family satisfaction with care in ICU

Seven studies, four of which were large multicentre studies, investigated family satisfaction with care and decision‐making in the ICU. Three studies used quantitative methods (Heyland, Rocker, & Dodek, 2002; Hunziker et al., 2012; Hwang et al., 2014) and four were mixed methods studies (Clark, Milner, Beck, & Mason, 2016; Hendrich et al., 2011; Karlsson, Tisell, Engrstom, & Andershed, 2011; Schwarzkopf et al., 2013). No qualitative studies of family satisfaction with care in ICU were found (Table 2). Six of the quantitative studies evaluated family satisfaction using the Family Satisfaction‐ICU (FS‐ICU) questionnaire and one used the Critical Care Family Satisfaction Survey (CCFSS).

Table 2.

Family satisfaction studies

| Author | Aim | Setting | Sample Size | Method | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clark et al. (2016) | To measure family satisfaction with care in a medical and surgical ICU | One general ICU in America | Forty family members |

Quantitative/Qualitative FS‐ICU with analysis of qualitative questions |

Overall, family satisfaction with care and decision‐making was good. 50% of family members reported the need for more timely and accurate information |

| Hwang et al. (2014) | To describe family satisfaction with care in a Neurological ICU and Medical ICU | One neurological ICU in America | Hundred and twenty‐four family members |

Quantitative FS‐ICU |

Less than 60% of ICU's families were satisfied by frequency of physician communication |

| Heyland et al. (2002) | To determine the level of satisfaction of family members with the care that they and their critically ill relative received | Six general ICUs at university hospital across Canada | Six hundred and twenty‐four family member |

Quantitative FS‐ICU |

Majority of respondents satisfied with overall care and decision‐making. Greatest satisfaction with nursing skill and competence, compassion and respect and pain management. Least satisfied with frequency of communication and waiting room atmosphere |

| Hendrich et al., 2011) | To describe the qualitative findings from a family satisfaction survey | Twenty three mixed ICUs across Canada | Eight hundred and eighty‐eight family members |

Qualitative/Quantitative FS‐ICU with analysis of qualitative questions |

Six themes identified central to family satisfaction. Positive comments were more common for: quality of the staff (66% vs. 23%), overall quality of medical care provided (33% vs. 2%), and compassion and respect shown to the patient and family (29% vs. 12%). Positive comments were less common for: communication with doctors (18% vs. 20%), waiting room (1% vs. 8%), and patient rooms (0.4% vs. 5%) |

| Hunziker et al. (2012) | To determine what factors ascertainable at ICU admission predicted family members dissatisfaction with ICU care | Nine mixed ICUs in the USA | Four hundred and forty‐five family members |

Quantitative FS‐ICU |

The most strongly associated factors reported by families relate to nursing competence, followed by completeness of information, and concern and caring of patients by intensive care unit staff |

| Karlsson et al. (2011) | To describe family members satisfaction with the care provided in a Swedish ICU | One general ICU in Sweden | Thirty‐five family members |

Quantitative/ Qualitative Critical Care Family Satisfaction Survey (CCFSS) |

Family members need for regular information was highlighted. The ICU staff's competence was also seen to be important for family members satisfaction with care |

| Schwarzkopf et al. (2013) | To assess family satisfaction in the ICU and areas for improvement using quantitative and qualitative analyses | Four (2 surgical, 1 medical and 1 neurological) ICUs in a hospital in Germany | Two hundred and fifty family members |

Qualitative/Quantitative FS‐ICU with analysis of qualitative questions |

Overall satisfaction with care and satisfaction with information and decision‐making based on summary scores was high. No patient or family factors predicted overall satisfaction, including patient survival |

Research study findings suggest that families of the critically ill are highly satisfied with the care their relative receives, especially with aspects of care about skill and competence of staff and the respect given to the patient (Clark et al., 2016; Hendrich et al., 2011; Heyland et al., 2002; Hunziker et al., 2012; Hwang et al., 2014; Schwarzkopf et al., 2013). Families were less satisfied with emotional support, the provision of understandable, consistent information and coordination of care (Clark et al., 2016; Hendrich et al., 2011; Heyland et al., 2002; Hunziker et al., 2012; Hwang et al., 2014; Schwarzkopf et al., 2013). Families felt more satisfied when clear, honest information was delivered to them in understandable language as this enables them to actively participate in the decision‐making process (Heyland et al., 2002; Hunziker et al., 2012; Hwang et al., 2014). One study by Heyland et al. (2002) found completeness of information was the single most important factor accounting for the variability in overall satisfaction. Families who rated the completeness of information highly were much more likely to be completely satisfied with their ICU experience. In another study, families were less satisfied not by the delivery of information received but by the lack of information received from medical staff (Hwang et al., 2014). When family satisfaction with care was measured using the CCFSS, overall satisfaction with care was high, however, similar to Hwang et al., (2014), dissatisfaction among some family members related to the lack of availability of medical staff for regular meetings (Karlsson et al., 2011).

Reporting on the three open‐ended questions in the FS‐ICU, three of the six studies provided further knowledge of family member's experiences with care delivery in the ICU (Clark et al., 2016; Hendrich et al., 2011; Schwarzkopf et al., 2013). In the free‐text responses, families expressed the need for better communication with healthcare staff and the need for timely, accurate and up‐to‐date information about changes in their relative's condition.

3.3. Theme 3 Factors having an impact on family well‐being and capacity to cope

Two key factors were identified in relation to the factors impacting on family well‐being and capacity to cope, namely anxiety and uncertainty.

3.3.1. Anxiety

Eight studies examined anxiety in family members of the critically ill (Table 3). Seven of these studies adopted quantitative approaches (Day, Bakin, Lubchansky, & Mehta, 2013; Delva et al., 2002; Paparringopoulos et al., 2006; Pochard et al., 2001, 2005; Rodriguez & San Gregorio, 2005; Young et al., 2005) and one study a qualitative approach (Iverson et al., 2014). Most studies were single centre. Levels of anxiety in family members were mainly measured 24–72 hr after the patient's admission to ICU. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms in these studies ranged from 40%–73% (Pochard et al., 2005). Risk factors associated with an increase in symptoms of anxiety included being female, a spouse, an unplanned ICU admission, lower educational status, poor sleep pattern, fatigue, lack of regular meetings with medical staff and failing to meet family needs (Day et al., 2013; Delva et al., 2002; Paparringopolous et al., 2006; Pochard et al., 2001, 2005). Whilst symptoms may reduce over time, Paul and Rattray, (2008) in a recent review of the literature highlighted that moderate to high levels of anxiety are present for up to 2 years after hospital discharge in relatives providing care after ICU.

Table 3.

Studies of psychological outcomes

| Author | Aim | Setting | Sample Size | Method/Measures | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agard and Harder (2007) | To explore and describe the experiences of relatives of critically ill adults | One neurosurgical and One General ICU in Denmark | Four spouses and 3 parents |

Qualitative Grounded theory |

Relatives were both vulnerable and resourceful simultaneously. They tried to fit in though using 3 strategies

They needed information all of the time and if not received formed their own personal cues leading to misunderstandings |

| Burr (1998) | To explore family needs and experiences and gain insight into nurse/family roles | Mixed ICU in teaching four hospitals in Australia |

Hundred and five family members CCFNI 26 Interviews |

Quantitative/Qualitative CCFNI/ semi‐structured interviews |

Two major needs emerged from the interviews that are not represented on the CCFNI: The need of family members to provide reassurance and support to the patient; and their need to protect |

| Day et al. (2013) | To investigate sleep quality, levels of fatigue and anxiety in families of critically ill adults | One medical and surgical ICU in Canada | Ninety‐four family members |

Quantitative General Sleep disturbance scale Beck Anxiety Inventory Scale Lee's Numerical Scale for fatigue |

The most common factor associated with poor sleep was anxiety (43.6%), tension (28.7%) and fear (24.5%). The need for more information and greater frequency of updates was cited by family members as a possible solution for reducing anxiety and promoting sleep |

| Delva et al. (2002) | To explore the needs and anxiety of family members of patients admitted to the ICU | One surgical ICU and One medical ICU in Belgium | Two hundred family members |

Quantitative State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) CCFNI |

The younger the patient the more anxious the family member was (p=0.0048). Females were more anxious than males (p < 0.01) and state anxiety was higher with non‐planned rather than planned admissions (p<0.01).Lower educational level predicted higher anxiety (p<0.001) Top 2 needs identified were for information and assurance |

| Iverson et al. (2014) | To explore surrogate decision makers challenges | Two general ICUs in the USA | Thirty‐four family members |

Qualitative Semi‐structured Interviews |

Anxiety influenced surrogate decision makers confidence in making decisions. This stress can be minimized by improving communication between these family members and the medical team |

| Jamerson et al. (1996) | To describe the experiences of families with a relative in ICU | One surgical/trauma ICU in the USA | Twenty family members |

Qualitative Focus Groups |

4 categories of experiences were identified:

|

| Johansson et al. (2005) | To gain an understanding of what relatives experience as supportive when faced with the situation of having a next of kin admitted to ICU | One general ICU in Sweden | Twenty‐nine family members |

Qualitative Grounded theory |

The ICU situation for relatives was characterized by uncertainty as to whether the patient would survive or suffer functional impairment, and a fear of complications arising |

| Pochard et al. (2001) | To determine the prevalence and factors associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of ICU patients | Fort‐three mixed (37 adult and six paediatric) ICUs in France | Nine hundred and twenty family members |

Quantitative HADS |

Symptoms of anxiety and depression common (69.1% and 35.4%, respectively) among family members visiting patients 3–5 days after admission to the ICU. Symptoms of anxiety were independently associated with being the spouse, female, lack of regular meetings with nursing and medical staff symptoms of depression were also associated being the spouse, female sex, contradictions in information |

| Pochard et al. (2005) | To determine the prevalence and factors associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members at the end of ICU stay | Seventy‐eight mixed ICUs in France | Five hundred and forty‐four family members |

Quantitative Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) |

Symptoms of anxiety and depression common (73.4% and 35.3%, respectively) at the end of their ICU stay. Symptoms of depression were more prevalent in non‐survivors (48.2%) than survivors (32.7%). A high severity of illness and younger patient age on admission predicted both anxiety and depression |

| Paparrigopoulos et al. (2006) | To evaluate the short term psychological impact on family members of intensive care patients during their stay in ICU | Two general ICUs in Greece | Thirty‐two family members |

Quantitative: Centre for Epidemiological Depression scale, the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the impact event scale. |

Symptoms of anxiety, depression and post‐traumatic stress common (60.4%, 97% and 81%, respectively) at first assessment. On second assessment, symptoms decreased but remained high (47%, 87% and 59%). Females and spouses exhibited higher levels of anxiety |

| Rodriguez &San Gregorio (2005) | To evaluate whether certain variables (Anxiety, depression, Quality of life) impacted on family members on ICU admission and 4 years later | One Neurosurgical ICU in Spain | Fifty‐seven family members |

Quantitative Psychosocial questionnaire developed by authors Clinical Analysis Questionnaire Family Environment Scale Fear of Death Scale |

High anxiety depression, apathy withdrawal and paranoia scores were high during ICU admission compared to scores obtained 4 years later Relative's scores for “fear of their own death” were lower on ICU admission compared to 4 years later |

| Young et al. (2005) | To investigate symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients and families after ICU discharge | ICU follow‐up clinic in the UK | Fifteen family members, 20 relatives |

Quantitative HADS |

Relatives were more anxious than patients |

3.3.2. Uncertainty

Five qualitative mainly single‐centre studies explored the uncertainty that families face when a relative is admitted to ICU and how this contributes to feelings of anxiety and inability to cope with the magnitude of the situation (Agard & Harder, 2007; Burr 1998; Iverson et al., 2014; Jamerson et al., 1996; Johansson, Hildingh, & Fridlund, 2005) (Table 3). Families describe their ongoing uncertainty about whether their family member will survive or suffer permanent disability, and having the daily fear of complications arising (Johansson et al., 2005). The need to seek out information on the patient's condition and prognosis was a consistent theme in all the studies. Families felt they should always be at the bedside; they searched for cues from healthcare staff that indicated an improvement or deterioration in the patient's condition (Agard & Harder, 2007; Burr, 1998). When these cues were absent, symptoms of anxiety manifest due to the uncertainty of the situation and they sought reassurance from staff that their relative was in safe hands. It was the “not knowing” that was the worst part of their entire ICU experience which often lead to misunderstandings and profound feelings of uncertainty, anxiety and distress until enough information was given or obtained (Agard & Harder, 2007; Burr, 1998; Iverson et al., 2014). In one study, Iverson et al. (2014) reported the role of surrogate decision maker amplified family members’ anxiety at an already challenging time; they were afraid that they were making the “wrong” decision on behalf of their loved one.

3.4. Theme 4 Psychosocial interventions

Seven studies investigated interventions to improve family needs, family satisfaction with care and anxiety and depression. These studies included four randomized controlled trials (RCT's) (Azoulay et al., 2002; Jones et al., 2004; Lautrette et al., 2007; Yousefi, Karami, Moeini, & Ganji, 2012) (Table 4) and three quasi‐experimental studies (Appleyard et al., 2000; Chien, Chui, Lam, & LP WY., 2006; Mitchell et al., 2009) (Table 4). Two of the RCTs examined family satisfaction with care as the primary outcome (Azoulay et al., 2002; Yousefi et al., 2012), whilst two trials investigated post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and symptoms of anxiety and depression as outcomes (Jones et al., 2004; Lautrette et al., 2007). Two quasi‐experimental studies investigated the effect of needs‐based interventions on family satisfaction (Appleyard et al., 2000; Chien et al., 2006), and a third study examined respect, collaboration and support (Mitchell et al., 2009).

Table 4.

Psychosocial Interventions

| Author | Aim | Setting | Sample Size | Method/Measures | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appleyard et al. (2000) | To gain knowledge and understanding of the role of volunteers pay in the critical care family waiting room | One general ICU in the USA | Fifty‐eight family members |

Quantitative Quasi‐experimental study with pre and post‐test design, without control group |

Increased family satisfaction from comfort needs only |

| Azoulay et al. (2002) | To determine whether a standardized family information leaflet improved satisfaction and comprehension of the information provided to family members of ICU patients | Thirty‐four General ICU in France |

Family members Intervention Group = 87 Control Group = 88 |

Quantitative A multicentre, prospective, randomized controlled trial (RCT) (Blinded) |

Increased family satisfaction and improved comprehension of information |

| Jones et al. (2004) | To evaluate the effectiveness of the provision of information in the form of a rehabilitation programme following critical illness in reducing psychological distress in the patients’ close family. | Three General ICU in UK |

Family members Intervention Group = 56 Control Group = 46 |

Quantitative Randomized controlled trial, blind at follow‐up with final assessment at 6 months. |

High incidence of psychological distress which did not reduce postintervention |

| Chein et al. (2006) | To examine the effect of a needs‐based education programme provided within the first 3 days of patients' hospitalization, on the anxiety levels and satisfaction of psychosocial needs of their families. | One General ICU in Hong Kong |

Family members Intervention group = 34. Control Group = 32 |

Quantitative Quasi‐experimental with pre‐ and post‐test design. |

Reduced anxiety. Increased satisfaction of family members. |

| Lautrette et al. (2007) | To evaluate the effect of a proactive communication strategy that consisted of an end‐of‐life family conference conducted according to specific guidelines and that concluded with the provision of a brochure on bereavement. | Twenty‐two (10 medical, 3 Surgical and 9 General) ICUs in France |

Family members Intervention Group = 56 Control group = 52 |

Quantitative Multicentre RCT |

Decreased the risk of symptoms of post‐traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression |

| Mitchell et al. (2009) | To evaluate the effects on family‐centred care of having critical care nurses partner with patients’ families to provide fundamental care to patients. | Two General ICUs in the USA |

Family members Intervention Group = 99 Control Group = 75 |

Quantitative Quasi‐experimental with pre‐ and post‐test design |

Improved respect, collaboration, support and overall scores of family‐centred care |

| Yousefi et al. (2012) | To determine the effectiveness of nursing interventions based on family needs on family satisfaction level of hospitalized patients in the neurosurgery ICU | One neurosurgical ICU in Iran |

Family members Intervention group = 32, Control group = 32 |

Quantitative Multicentre RCT |

Increased satisfaction of families |

Overall, a diverse range of interventions were used in these studies with the aim of improving the number of family needs met, improving satisfaction and psychological well‐being. Azoulay et al. (2002) distributed a family information leaflet to supplement standardized family meetings to assess whether it improved their understanding of diagnosis and proposed interventions. The leaflet improved comprehension of diagnosis and treatment but not of prognosis. The authors attributed this to the focus of the leaflet being on diagnosis and treatment and that understanding the prognosis is difficult for families. Satisfaction with care did not significantly differ between the two groups. However, although not statistically significant they reported the family information leaflet did improve satisfaction among those family members with good comprehension. Yousefi et al. (2012) examined whether family satisfaction was improved by allocating families with a dedicated ICU support nurse. The intervention was based on “family needs inventory” where the ICU nurses role was to provide accurate explanations and information to families about the patient and their critical illness. Information and explanations were given about the ICU environment, equipment and personnel as well as treatment, diagnosis and prognosis. Meetings with the physician and allied health professionals were also facilitated. Satisfaction in the intervention group was significantly increased postintervention. Lautrette et al. (2007) introduced use of a bereavement brochure along with a proactive family conference for relatives of patients in ICU with high likelihood of mortality. They found significantly fewer symptoms of post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and depression after 90 days. In contrast, Jones et al. (2004) failed to show the provision of general written information around recovery after ICU delivered by nurses in 3 ICUs reduced anxiety, depression and PTSD symptoms at eight weeks and six months after ICU discharge. Some relatives remained anxious, and they met criteria for PTSD.

Other studies have looked at the effect of relatives assisting with the provision of care to the patient (Appleyard et al., 2000; Chien et al., 2006; Mitchell et al., 2009). Results from quasi‐experimental studies suggest better family satisfaction and reduced emotional distress postintervention, compared with the usual care group (Appleyard et al., 2000; Chien et al., 2006; Mitchell et al., 2009). For example, Chien et al. (2006) found that performing needs‐based training on the patient's family needs assessed on admission to ICU, decreased anxiety and increased their satisfaction. The intervention itself was labour intensive, and further research is required to identify which specific aspects of the programme were effective. Further, Appleyard et al. (2000) reported greater family satisfaction about comfort needs following the introduction of a volunteer programme in the ICU but no differences were found for the other CCFNI factors, including information, assurance, proximity and support. Notably, the volunteers reported the nurses became more communicative and more concerned about families’ needs following the introduction of the intervention. In the third study, Mitchell et al. (2009) reported that encouraging patient's family members to assist in providing care to their relatives significantly improved respect, collaboration, support and overall satisfaction. This study, however, only included the relatives of long‐term ICU patients with a length of stay greater than 11 days, thereby limiting the results to this group.

4. DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to describe published literature on the needs and experiences of family members of adult critically ill patients and interventions to improve family satisfaction and psychological health and well‐being. Forty research studies and three review articles were included in the review.

Family needs were investigated primarily through use of the CCFNI which highlights the most pressing family needs as being for information and reassurance followed by proximity, comfort and support, respectively. Families want honest and up‐to‐date information delivered daily in understandable terms about their relative's progress, without leaving room for unrealistic hope (Auerbach et al., 2005). They also want to be contacted anytime of the day or night if their relative's clinical condition changes and to be reassured they are receiving the best possible care (Omari, 2009). From their experiences, families felt there was a need to develop a trusting and mutually respectful relationship with healthcare staff and that this helped them adjust to the situation they were faced with (Bond et al., 2003; Fry & Warren, 2007; Keenan & Joseph, 2010).

Fulfilling family needs is important as unmet needs leave family members feeling uninformed, dissatisfied and disenfranchised from clinical decision‐making and with the day‐to‐day care of their relative (Wall, Curtis, Cooke, & Engelberg, 2007). The ability to meet or satisfy family needs is one of the main challenges that healthcare staff encounter in the ICU. Even if families’ needs are known to ICU staff, studies have indicated that these needs are not always met (Hinkle et al., 2009; Leung et al., 2000; Omari, 2009).

To improve the quality of care provided to families assessing families’ satisfaction with the patient care delivered, particularly in ICU, is important for several reasons. Firstly, healthcare providers need to develop open collaborative and supportive relationships with family members to enable them to cope with their distress and speak for the patient. Secondly, the collection of objective data on family satisfaction is desirable to assess how well healthcare providers are doing in this area. Data on family satisfaction are measured as a surrogate marker of the quality of their care (Heyland & Tranmer 2001).

Key areas for improvement identified were including the family as part of the ICU team, increasing open communication and assessing and potentially revisiting their level of understanding of the information they have been given (Clark et al., 2016; Hendrich et al., 2011; Heyland et al., 2002; Hunziker et al., 2012; Hwang et al., 2014; Schwarzkopf et al., 2013). Nurses who are in constant close contact with families are in an ideal position to ensure that family information and assurance needs are met. However, according to research, some nurses lack confidence in providing information, often being afraid of not giving the correct information or not providing adequate answers (Engstrom & Soderberg, 2007; Soderstrom, Saveman, Hagberg, & Benzein, 2003; Stayt, 2007). This is thought to be the case because nurses believe they are educationally underprepared and not sufficiently qualified to give the level of information required (Krimshtein et al., 2011; Stayt, 2007). Medical staff on the other hand have difficulty meeting with families and providing regular information delivered in a way families understand (Heyland et al., 2002; Hunziker et al., 2012; Hwang et al., 2014). Poor communication skills, insufficient training, delivering patient rather than family‐centred care and a lack of time have been attributed to this (Azoulay et al., 2000; Bijttebeir et al., 2001; Moreau et al., 2004).

Several studies highlighted additional factors that have an impact on family needs being met and their capacity to cope. Symptoms of anxiety are elevated at the onset of critical illness, and the uncertainty of their family members condition exacerbate these symptoms (Pochard et al., 2005). From clinical experience and research, high levels of anxiety and uncertainty result in family members overestimating or underestimating the risks and/or benefits of clinical treatments, impairs comprehension and decision‐making capabilities (Azoulay et al., 2000; Pochard et al., 2001). Anxiety therefore has important implications for family members who participate regularly in decisions about the care of their relative. Providing timely information, and preparing families for transitions in the delivery of care, may minimize the uncertainty and anxiety they experience (Azoulay et al., 2000).

Identifying interventions for supporting family members of the critically ill during the acute phase of their illness is necessary because if their relative survives, they are likely to care for them during a prolonged and often difficult recovery period (Pochard et al., 2005). The components of the interventions reviewed included a range of tools or strategies, for example family information booklet, bereavement brochure, structured meetings and dedicated nurse support (Appleyard et al., 2000; Azoulay et al., 2002; Chien et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2004; Lautrette et al., 2007; Mitchell et al., 2009; Yousefi et al., 2012).

From the intervention studies reviewed, providing a combination of targeted written and oral information delivered by nursing and medical staff caring for the patient significantly increased satisfaction and reduced anxiety with this reduction being sustained over time (Chien et al., 2006; Lautrette et al., 2007; Yousefi et al., 2012). Reasons for this pattern are because families were provided with good knowledge about their relative's clinical condition and treatment and contacted through the day either by phone or by attending a family meeting. These phone calls or meetings ensured families received updated information, had an opportunity to get questions answered and support when difficult decisions needed to be made. Additionally, families conveyed greater satisfaction with needs met if they received information about the ICU environment and equipment either through leaflets or discussions with staff and were involved in care of the patient at the bedside (Lautrette et al., 2007). Thus, not maintaining continuous and multiple methods of communication with the family delivered by the ICU team could account for the lack of positive statistically significant results in the other intervention studies (Appleyard et al., 2000; Azoulay et al., 2002; Jones et al., 2004; Mitchell et al., 2009).

Providing high‐quality information in a variety of ways ensuring that family members understand the nature of their relative's condition, including diagnosis, prognosis and treatment risks and benefits, is crucial for family members to cope with their role as substitute decision makers (Azoulay et al., 2000, 2001; Bond et al., 2003). Azoulay, Kentish‐Barnes, and Nelson (2016) suggest that discussions with families open with the question “What is your understanding of what the clinical team expects to happen?” or “What has the team told you about what to expect?” If the answer differs from that of the medical staff, then this is the best place to start to identify the source of the discordance. Intensive care units that are able to support interventions based on meeting family information needs, in addition to reducing psychological burden and increasing satisfaction, will enable each family to provide more support to their relative in the ICU.

4.1. Limitations of the review

Only English‐language articles were considered for inclusion in this scoping review. As such, this review misses potentially relevant articles written in other languages, which primarily covers research conducted in America. Most of the studies in this review involved female family members of the critically ill. Most studies obtained data from family members within 24–72 hr of admission to the ICU, which could affect the validity of the data because family members experience intense emotions and stress during these times.

Although experimental studies were identified, there were some methodological weaknesses. Most studies were descriptive, non‐experimental, single‐centre studies with small sample sizes, as such their findings may not be generalizable. There was an absence of theory to frame or guide the intervention, and each study identified limitations in their study design and outcome measures. Differences in study design, population, the number of samples and methods of intervention make it difficult to compare the results. Several of the studies measured the effect of the interventions in reducing family's anxiety; however, it is difficult to ascertain whether the reduction in anxiety is because of the intervention itself or the level of severity of the patient's illness.

4.2. Future research

There is a need for further empirical research to increase understanding of family needs and their perspective of whether their needs were met or not and the factors that militate against this. Differences in perceptions of need should be identified and examined from the perspectives of family and ICU staff over time. More studies are needed into the effectiveness of interventions in ITU and their core components to help improve family members’ satisfaction with care and their psychological health and well‐being. Future research might want to include family in the design of interventions, provide details of the implementation process and have clearly identified outcomes.

5. IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Family members’ need for information and assurance is perceived as being the most important need when their relative is admitted to the ICU. One major clinical implication of these results is that healthcare staff's ability to meet or satisfy these needs is not always achieved.

Family members of patients who are admitted to ICU experience increased psychological burden, yet few studies were found on the effectiveness of interventions to improve their health and well‐being.

Regular structured family meetings using targeted written and oral information are suggested to ensure families receive the informational support required. More research is needed in this area to add to the evidence base on the effectiveness of interventions to support family members in ICU

6. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this scoping review identified four key themes that emerged from the literature. A key finding from this review is that studies of family need have received most attention and consistently identified the need for more information and reassurance. However, families’ perceived needs were not always met by healthcare staff and this had a negative impact on family satisfaction and their psychological health and well‐being. Whilst there is some evidence that interventions based on the provision of appropriate written and oral information in ICU can effectively reduce anxiety and improve satisfaction, more empirical research is needed in this area.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

None.

Scott P, Thomson P, Shepherd A. Families of patients in ICU: A Scoping review of their needs and satisfaction with care. Nursing Open. 2019;6:698–712. 10.1002/nop2.287

The review is part of the main authors taught clinical doctorate in nursing at the University of Stirling. The author's academic supervisors provided support and advice during the author writing this review article. It has not been published elsewhere.

Ashley Shepherd and Patricia Thomson—The lead author's academic supervisors provided support and advice during the author writing this review article.

Funding Information

Forth Valley Royal Hospital.

REFERENCES

- Agard, A. S. , & Harder, L. (2007) Relatives experiences in intensive care‐finding a place in a world of uncertainty. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 23, 170–177. 10.1016/j.iccn.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Mustair, A. S. , Plummer, V. , O'Brien, A. , & Clerehan, R. (2013). Family needs and involvement in the intensive care unit: A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22, 1805–1817. 10.1111/jocn.12065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard, M. E. , Gavaghan, S. , Gonzalez, C. , Ananian, L. , Tyrell, R. , & Carroll, D. (2000). Nurse coached interventions for families for families of patients in critical care units. Critical Care Nurse, 20, 40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H. , & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, S. M. , Kiesler, D. J. , Wartella, J. , Rausch, S. , War, K. R. , & Ivatury, R. (2005). Optimism, satisfaction with needs met, interpersonal perceptions of the healthcare team and emotional distress in patients family members during critical care hospitalisation. American Journal of Critical Care, 14(3), 202–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay, E. , Chevret, S. , Leleu, G. , Pochard, F. , Barboteu, M. , Adrie, C. , … Schlemmer, B. (2000). Half of families of intensive care patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Critical Care Medicine, 28(8), 3044–3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay, E. , Kentish‐Barnes, N. , & Nelson, J. E. (2016). Communication with family caregivers in the intensive care unit: Answers and questions. JAMA, 315(19), 2075–2077. 10.1001/jama.2016.5637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay, E. , Pochard, F. , Chevret, S. , Jourdain, M. , Bornstain, C. , Wernet, A. , … & Lemaire, F. (2002). Impact of a family information leaflet on the effectiveness of information provided to family members of intensive care unit patients. A multicentre prospective randomised control trial. American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine, 165, 438–442. 10.1164/ajrccm.165.4.200108-006oc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay, E. , Pochard, F. , Chevret, S. , Lemaire, F. , Mokhtari, M. , Le gall, J.‐R. , … Schlemmer, B. (2001). Meeting the Needs of Intensive Care Unit Patient Families : A Multicenter Study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 163(1), 135–139. 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2005117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijttebeir, P. , Vanoost, S. , Delva, D. , Ferdinande, P. , & Frans, E. (2001). Needs of relatives of critical care patients: Perceptions of relatives, physicians and nurses. Intensive Care Medicine, 27(1), 160–165. 10.1007/s001340000750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond, E. , Draeger, C. R. , Mandleco, B. , & Donnelly, M. (2003). Needs of family members of patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Critical Care Medicine, 23(4), 63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr, G. (1998). Contextualising critical care family needs through triangulation: An Australian study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 14(4), 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien, W. T. , Chui, Y. L. , Lam, L. W. , & Wan‐Yim, L. P. (2006). Effects of a needs – based education programme for family carers with a relative in an intensive care unit: A quasi‐experimental study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43, 39–50. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K. , Milner, K. , Beck, M. , & Mason, V. (2016). Measuring family satisfaction with care delivered in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Nurse, 36(6), 8–14. 10.4037/ccn2016276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day, A. , Bakin, H. , Lubchansky, S. , & Mehta, S. (2013). Sleep, anxiety and fatigue in family members of patients admitted to the intensive care unit: A questionnaire. Critical Care, 17, 698–7. 10.1186/cc12736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delva, D. , Vanoost, S. , Bijttebeir, P. , Lauwers, P. , & Wilmer, A. (2002). Needs and feelings of anxiety of relatives of patients hospitalised in intensive care units: Implications for social work. Social Work in Health Care, 35, 21–40. 10.1300/J010v35n04_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engström, A. , & Söderberg, S. (2007). Receiving power through confirmation: The meaning of close relatives for people who have been critically ill. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 59, 569–576. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04336.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaatten, H. (2012). The present use of quality indicators in the intensive care unit. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 56(9), 1078–1083. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2012.02656.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry, S. , & Warren, N. A. (2007). Perceived needs of critical care family members: A phenomenological discourse. Critical Care Nursing., 30(2), 181–188. 10.1097/01.CNQ.0000264261.28618.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, N. J. , Dodek, P. , Heyland, D. , Cook, D. , Rocker, G. , Kutsogiannis, D. , … Ayas, N. (2011). Qualitative analysis of an intensive care unit family satisfaction survey. Critical Care Medicine, 39(5), 1000–1005. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820a92fb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyland, D. K. , Rocker, G. M. , & Dodek, P. M. (2002). Family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: Results of a multiple centre study. Critical Care Medicine, 30, 1413–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyland, D. K. , & Tranmer, C. J. E. (2001). Measuring family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: The development of a questionnaire and preliminary results. Journal of Critical Care Medicine., 16(4), 142–144. 10.1053/jcrc.2001.30163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle, J. , & Fitzgerald, E. (2011). Needs of American relatives of intensive care patients: Perceptions of relatives, physicians and nurses. Intensive and Critical Nursing, 27(4), 218–225. 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle, J. , Fitzpatrick, E. , & Oskrochi, G. (2009). Identifying the perception of needs of family members visiting and nurses working in the intensive care unit. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 41(2), 85–91. 10.1097/JNN.0b013e31819c2db4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunziker, S. , McHugh, W. , Sarnoff‐Lee, B. , Cannistraro, S. , Ngo, L. , Marcantonio, E. , & Howell, M. D. (2012). Predictors and correlates of dissatisfaction with intensive care. Critical Care Medicine, 40, 1554–1561. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182451c70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, D. Y. , Yagoda, D. , Perrey, H. M. , Tehan, T. M. , Guanci, M. , Ananian, L. , … Rosand, J. (2014). Assessment of satisfaction with care among family members of survivors in a neuroscience intensive care unit. Journal of American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, 46(20), 106–116. 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (2017),https://onlinereports.icnarc.org/Reports/2017/12/annual-quality-report-201617-for-adult-critical-care.

- Iverson, E. , Celion, A. , Kennedy, C. , Shehane, E. , Eastman, A. , Warren, V. , & Freeman, B. (2014). Factors affecting stress experienced by surrogate decision‐makers for critically ill patients: Implications for nursing practice. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 30(2), 77–85. 10.1016/j.iccn.2013.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamerson, P. A. , Scheibmeir, M. , Bott, M. , Crighton, F. , Hinton, R. , & Cobb, A. K. (1996). The experiences of families with a relative in the intensive care unit. Heart and Lung, 25, 467–473. 10.1016/S0147-9563(96)80049-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, I. , Hildingh, C. , & Fridlund, B. (2005). What is supportive when an adult next‐of‐kin is in critical care? Nursing in Critical Care, 10(6), 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C. , Skirrow, P. , Griffiths, R. D. , Humphries, G. , Ingelby, S. , Eddleston, J. , … Gager, M. (2004). Post‐Traumatic Stress – related symptoms in relatives of patients following intensive care. Intensive Care Medicine., 30, 456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, C. , Tisell, A. , Engrstom, A. , & Andershed, B. (2011). Family members' satisfaction with critical care: A pilot study. Nursing in Critical Care, 16(1), 11–18. 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2010.00388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, A. , & Joseph, L. (2010). The needs of family members of severe traumatic brain injured patients during critical and acute care: A qualitative study. Canadian Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 32(3), 25–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinrade, T. , Jackson, A. , & Tomany, J. (2010). The psychosocial needs of families during critical illness: Comparison of nurses’ and family members’ perspectives. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Krimshtein, N. , Luhrs, C. , Puntillo, K. , Cortex, T. , Livote, E. , Penrod, E. , & Nelson, J. (2011). Training Nurses for Interdisciplinary Communication with Families in the Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 14(12), 1325–1332. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautrette, A. , Darmon, M. , Megarbane, B. , Joly, L. M. , Chevret, S. , Adrie, C. , … Azoulay, E. (2007). A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. New England Journal of Medicine, 356, 469–478. 10.1056/NEJMoa063446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L. Y. , & Lau, Y. L. (2003). Immediate needs of adult family members of adult intensive care patients in Hong Kong. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12, 490–500. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00743.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung, K. , Chien, W. T. , & Mackenzie, A. E. (2000). Needs of Chinese Families of Critically Ill Patients. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 22(7), 826–840. 10.1177/01939450022044782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M. , Burmeister, C. W. , & E & Foster M,, (2009). Positive effects of a nursing intervention on family centred care in adult critical care. American Journal of Critical Care, 8(6),543, 542 10.4037/ajcc2009226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molter, N. (1979). Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: A descriptive study. Heart and Lung., 8, 332–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, D. , Goldgran‐Toledano, D. , Alberti, C. , Jourdain, M. , Adrie, C. , Annane, D. , … Azoulay, É. (2004). Junior versus senior physicians for informing families of intensive care unit patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care, 169(4), 512–517. 10.1164/rccm.200305-645OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omari, F. (2009). Perceived and unmet needs of adult Jordanian family members of patients in ICUs. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 1, 28–34. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01248.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbayir, T. , Tasdemir, N. , & Ozseker, E. (2014). Intensive care unit family needs: Nurses' and families perceptions. Eastern Journal of Medicine, 19, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Paparrigopoulos, T. , Melissaki, A. , Efthymiou, A. , Tsekou, H. , Vadala, C. , Kribeni, G. , … Soldatos, C. (2006). Short‐term psychological impact on family members of intensive care unit patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 61(5), 719–722. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul, F. , & Rattray, J. (2008). Short and long‐term impact of critical illness on relatives:Literature Review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(3), 272–292. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04568.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul, R. G. , & Finney, S. J. (2015). Family satisfaction with care on the ICU: Essential lessons for all doctors. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 76(9), 504–509. 10.12968/hmed.2015.76.9.504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pochard, F. , Azoulay, E. , Chevret, S. , Lemaire, F. , Hubert, P. , Canoui, P. , … Schlemmer, B. (2001). Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: Ethical hypothesis regarding decision making capacity. Critical Care Medicine, 29(10), 1893–1897. 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pochard, F. , Darmon, M. , Fassier, T. , Bollaert, P.‐E. , Cheval, C. , Coloigner, M. , … Azoulay, É. (2005). Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients before discharge or death: A prospective multicenter study. Journal of Critical Care, 20(1), 90–96. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, M. A. , & San, G. P. (2005). Psychosocial adaptation in relatives of critically injured patients admitted to an intensive care unit. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 8(1), 36–44. 10.1017/S1138741600004947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzkopf, D. , Behrend, S. , Skupin, H. , Westermann, I. , Riedemann, N. C. , Pfeifer, R. , … Hartog, C. W. (2013). Family satisfaction in the intensive care unit: A quantitative and qualitative analysis. Intensive Care Medicine, 39(6), 1071–1079. 10.1007/s00134-013-2862-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Intensive Care Society Audit Group (2017). Audit of Adult Critical Care in Scotland 2017 reporting on 2016. Retrieved from www.sicsag.scot.nhs.uk/publications/docs/2017/2107-08-08-SICSAG-report.pdf.

- Scottish Intensive Care Society Audit Group (2018). Audit of Adult Critical Care in Scotland 2018 reporting on 2017. Retrieved from www.sicsag.scot.nhs.uk/publications/_docs/2018/2018-08-14-SICSAG-report.pdf.

- Söderström, I.‐M. , Saveman, B.‐I. , Hagberg, M. S. , & Benzein, E. G. (2003). Family adaptation in relation to a family member's stay in ICU. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 25(5), 250–257. 10.1016/j.iccn.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stayt, L. C. (2007). Nurse experiences of caring for families with relatives in intensive care units. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 57(6), 623–630. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takman, C. , & Severinsson, E. (2006). A description of healthcare providers perceptions of the needs of significant others in intensive care units in Norway and Sweden. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 22, 228–238. 10.1016/j.iccn.2005.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghe, S. , Defloor, T. , Van Zuuren, F. , Duijnstee, M. , & Grypdonck, M. G. (2005). The needs and experiences of family of adult patients in an intensive care unit : A review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 14, 501–509. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01081.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall, R. J. , Curtis, J. R. , Cooke, C. R. , & Engelberg, R. A. (2007). Family satisfaction in the ICU, Differences between families of survivors and non survivors. Chest, 132(5), 1425–1433. 10.1378/chest.07-0419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, E. , Eddleston, J. , Ingleby, S. , Streets, J. , McJanet, L. , Wang, M. , & Glover, L. (2005). Returning home after intensive care : A comparison of symptoms of anxiety and depressions in ICU and elective cardiac surgery patients and their relatives. Intensive Care Medicine, 31, 86–91. 10.1007/s00134-004-2495-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi, H. , Karami, A. , Moeini, M. , & Ganji, H. (2012). Effectiveness of nursing interventions based on family needs on family satisfaction in the neurosurgery intensive care unit. Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 17(4), 296–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]